[Minus three hundred and twenty]

I wake a couple of hours later to sunshine and a piece of chocolate cake on my doorstep. Actually, there’s a plate between it and the step, the difference between Thomas-now and Thomas-then. What other midnight baker would be leaving cake outside my room—Umlaut? He’s sniffing round my ankles. Tucked underneath the plate, to stop it from flying away, there’s a folded scrap of paper. In Thomas’s blocky print, it reads:

BEAT BUTTER AND SUGAR TILL CREAMED. STIR IN WHISKED EGGS, THEN FOLD IN SELF-RAISING FLOUR. USE 4 OZ OF EACH INGREDIENT PE`TWO EGGS. ADD 2 TBSP COCOA POWDER WITH THE FLOUR FOR CHOCOLATE. BAKE AT 150°C FOR AN HOUR. EVEN YOU CAN DO THIS. TRUST ME.

There are hydrangeas in bloom, the sun is shining, and I’ve finally slept. Alles ist gut. Confessing The Wurst, if not the worst, has left me somehow able to close my eyes. Are Thomas and I friends? Age twelve, if someone had asked me that, I’d have punched them in the nose. Our friendship just was, like gravity, or daffodils in spring.

I stand on the step with the cake, the note, the kitten, and this thought: we talked till the sun came up. And it only makes me want to say more. Next to me, Umlaut does flips in the sunshine.

I scoop him up and head to the kitchen, where I get my second surprise of the day—a new phone. This comes with a note, too, a more enlightening one: Sie sind verantwortlich für die Zahlung der Rechnung. Dein, Papa. (You’re in charge of paying the bill. Love, Papa).

I abandon my cake on the windowsill and tear open the phone like it’s Christmas morning, plugging it in to charge. Papa has Scotch-taped my old SIM onto the box. I’ll be able to see if Jason’s texted a time for us to meet. I’ll be able to ask him: what happened in Grey’s room—did I disappear?

And the real question: what happened, with us?

“Goog ’ake.”

I look up from my phone-charging vigil to see that a pajama-bottomed Ned, his hair wild, has emerged from his nest. Wednesdays and Fridays are his bookshop shifts, which means he’s up early-ish. And he’s eating my cake for breakfast.

“’Eckon.” He swallows in one gulp, like a snake, and tries again. “Think Thomas would make a massive one for the party?”

This is the first time he’s spoken to me directly about the party—but he still hasn’t asked me if I’m okay with it. For all the hydrangeas and sleep in the world, alles ist not gut. I grab my satchel and my partially charged phone and run out of the house.

* * *

My phone chimes along with the church bells. I’ve been hiding out in the churchyard for hours, folded like origami between the yew tree and the wall. The text is from Jason. We’re meeting at lunchtime, a week from tomorrow.

Notebooks and diaries are spread out around me on the yellowing grass. It’s out of sight of the church, the graves, the road. We came here once.

It was the beginning of August, about seven weeks after our first kiss. We hadn’t slept together yet, but suddenly I could see it on the horizon. Every day, everything—the air, the sunshine, the blood in my veins—was pulsing hot and urgent. The minute we were alone, our words and clothes would disappear. Grey’s diary for that day says: LOBSTER WITH WILD GARLIC BUTTER ON THE BARBECUE. Behind the tree, Jason’s hand slipped between my legs, and I bit his neck. I wanted to eat him.

Where did all that love go? Where did that girl go, who was so alive?

My phone emits a rapid flurry of beeps, and I swoop on it. But it turns out to be old messages from Sof, arriving all at once. A couple checking if I’m okay, after our beach spat, but mostly chattering about the party I don’t want to happen. There’s no way to answer those, so I throw the phone onto the grass instead and pick up a notebook.

The Weltschmerzian Exception.

It started the day I saw Jason again. I’m writing his name down when a shadow falls across the page. Thomas is peering round the tree.

“I’d say you’re avoiding me,” he remarks, flopping down opposite me, against the wall, “but I know you know I know all our hiding places.”

He stretches out his legs, putting his feet up on the trunk next to me, making himself practically horizontal. Whatever landscape he’s in, he folds himself into. I parse my way through his sentence, come up with: “So you’d say I’m … waiting for you?”

“If you say so.” A laugh bursts across his face.

Well, I walked into that one.

“You liked the cake?” he asks.

“Delicious,” I lie.

“Funny, Ned thought so too.”

Twelve years of stare-offs between us, and my impassive face is perfect. Finally Thomas blinks and says, “Okay, subject change. Is this your extra-credit project?”

He makes a “may I?” gesture and reaches for the notebook, which is balanced on my bare legs. His fingers graze my knees as he takes it, glancing at the pages and saying, “Senior year here must be intense.”

I peer over at what he’s reading. A page of impenetrable numbers, and standing out like a big red flag, Jason’s name. For some reason it seems important that Thomas not know this particular secret. Time for my own subject change.

“How’s the jet lag?”

“I think my time zones are still cuckoo.” Thomas yawns.

“As in the clock? They’re actually very efficient.” It’s this sort of fact-based fun, Sof informs me, that doesn’t get me invited to the parties I don’t want to go to.

“For real? Okay. Wackadoodle, then.” Thomas closes his eyes. There’s no cardigan today, he’s wearing a T-shirt with a pocket, which he tucks his glasses into. He looks less artfully constructed without them. More like someone I would be friends with. “I stayed up too late. Don’t lemme sleep, though,” he mumbles. “Keep talking.”

“I need a topic. Unless you’re interested in Copernicus.”

“Not Copper Knickers,” he says. “Umlaut. What’s up with that?”

“Papa brought him home in April.” I lean forward, lifting the notebook off Thomas’s knees as gently as I dare. But he opens his eyes and squints at me. In the sunshine, his flawed iris looks like a starburst nebula.

“G. That’s not talking. That’s information. I need details.”

“Okay. Um. I was doing homework in the kitchen after school, when this orange thing shoots out from under the fridge, scuttles across the room past the stove and into the woodpile. So I picked up a ladle—”

“A ladle?” mumbles Thomas, closing his eyes again.

“You know—for soup?” Maybe they call it something else in Canada. A ladleh.

He chuckles. “I know what a ladle is. I wanna know why you got a ladle.”

“I thought there was a mouse.”

“What were you gonna do, scoop it up?”

I rap him on the knee with my pencil, and he shuts up, smiling.

“Woodpile, scuttly thing, ladle, me,” I recap. As I name each thing, the picture in my head clarifies, and I suddenly remember what happened right before the ginger streak across the floor: the kitchen screenwiped. At the time I put it down to a headache. Has time been going round the twist since then? That’s three months ago.

“G?” Thomas murmurs sleepily, tapping me on the shoulder with his foot.

“Oh! Right. Then this kitten pops up from behind a log and it’s Umlaut.”

“That’s it?”

“Then I put him in my jumper and rang the bookshop, because I thought maybe Papa could put a sign up. And he answers and goes, ‘Guten tag, liebling. Did you get my note?’ I look around and he’s written on the blackboard, but it just says ‘Gottie? Cat.’”

When Thomas laughs at my story, his mouth crinkling, my brain bolt-from-the-blue redelivers the thought from the bookshop: I don’t remember you being this gorgeous.

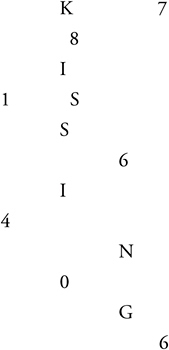

I start reciting pi to one hundred decimal places. Except my brain won’t play along, because it ends up going like this:

And I start to wonder: what would have happened if Thomas had kissed me five years ago? If he’d never left? Would I still have fallen in love with Jason, or would it have been Thomas I was behind this tree with last summer? When I let myself think this, the churchyard around us gradually fills with the numbers I was reciting in my head. They hang in the air like Christmas baubles, suspended on nothing. We’re flying through the galaxy, up in the stars. And it’s beautiful.

It’s Grey’s string theory: a giant cosmic harp. What would my grandfather say to me now? I imagine him stealing my notebook, peering at the Weltschmerzian Exception. “The rules of spacetime are buggered, are they? Make your own rules.”

“Thomas?” I ask. “That email you sent me. What was it?”

“Email? It’s a form of communication, sent through the In-ter-net.” Thomas pulls himself upright and does a cute little typey-typey motion with his hands to demonstrate. He’s oblivious to the mathematical weather phenomenon, to the thought that sparked it—a version of the world where we’d once kissed.

“Ha.” I prod him in the leg with my trainer, and he catches my ankle for an imperceptible moment, smiling, his face mirror-balled with light from the numbers.

“G, it’s no big deal,” he says. “I wrote you that, yeah, I was coming over. It was just a reply to yours.”

The numbers fall from the air, raining silver on the grass, where they fade away. We’re back to normal.

Normal—except there’s a timeline where I wrote Thomas an email!

“I guess I didn’t get what yours meant till I arrived,” he continues. “Your dad explained when he drove me from the airport. About Grey.”

A record scratch, a squeal of tires. I can pretend that life goes on, in stories of kittens and emails, but death brings it all to a screeching halt. My face slams shut and Thomas must know why, because he waves at the notebook and very carefully says, “Talk to me about timespace.”

“Spacetime,” I correct, awkwardly bum-shuffling around on the grass to sit next to him, grabbing hold of the latest subject change like a life raft. Our shoulders align. “Time travel. I’m still figuring out the rules. How it would work, if it were real.”

“Cool. Where would you go? I’m thinking dinosaurs. Or maybe the Age of Enlightenment, hang out with ol’ Copper Knickers.” He leans forward, his arm brushing against mine as he gestures out to the churchyard, almost snowy under its blanket of daisies. “Or stay here in Holksea, get some medieval times happening. Get my head stuck in the stocks again.”

“Last August,” I interrupt. “That’s where I’d go.”

“Boring,” he sing-songs. “What’s last August?”

Jason. Grey. Everything.

“Shit,” he says, realizing. “Sorry.”

“It’s okay.” I yank up a clump of dry grass and start shredding it. I don’t want to … Talking to Thomas last night, today—these have been the first conversations in forever where I haven’t felt brain-locked, searching for words to say …

Scheisse! I can’t even finish a sentence in my own head!

Next to me, Thomas puts his hand over my frantic ones, shushing them. The church bells ring out for six o’clock. A funeral chime.

“We should go,” I say. “Umlaut needs feeding.”

I scramble up, stuffing books haphazardly into my bag. Thomas scoops up half of them. As we pick our way through the grass, I see he’s holding Grey’s diaries.

“Is this where…” he trails off, obviously infected by the Gottie H. Oppenheimer disease of Never Being Able to Talk About the Worst Thing, looking round. “Is this … is Grey…?”

Oh, God. I’m übercreep. Reading a dead man’s diaries, surrounded by graves. This was always one of our hiding places, even though Mum’s buried on the other side of the church. But that’s different—she doesn’t belong to me in the same way that Grey did. She’s a stranger.

“No,” I say, too sharply. “He, we didn’t…” Deep breath. “There was a cremation.”

We shuffle along the path around the church in silence, leaving yew needle footprints behind. We pass Mum’s grave. It’s never not a shock, seeing the date covered in moss: my birthday. Her death. Carved in stone is the stark reality: that we only ever had a few hours together, before a blood clot, her brain, a collapse. And nothing anyone could do. Thomas leans down and scoops up a pebble in one fluid movement, placing it on top of the stone, keeps walking.

Another ritual. A new one. I like him.

“It’s nice that you have these,” Thomas says, gesturing with the diaries. “Like he’s still around. An idea I’m far more comfortable with now I know you painted The Wurst.”

I laugh. Sometimes it’s so easy to. Other times, it feels like I’m going to implode. And it can be totally at random, when I’m doing something irrelevant—showering. Eating a garlic pickle. Sharpening a pencil and suddenly, I’ll want to cry. I don’t get it. Denial, anger, bargaining, depression, acceptance. That’s what the books promised. What I’ve got instead is an uncertainty principle—I never know where my emotions are going to end up.

“I wish Mr. Tuttle had left diaries when he died.” Thomas elbows me.

I laugh, again. “Mr. Tuttle finally died? I thought he was everlasting.”

“He was actually six hamsters. My dad vetoed the endless resurrection last year. I think he was worried he’d get custody.”

We’ve reached the gate. Thomas turns around so quickly it makes me wobble. I end up standing way too close to him. But even though we’re inches apart, he’s in the blazing sunshine, and I’m in the shade.

“G. I wanted to say—back then. I haven’t told you, I really am sorry. About Grey.”

And he hugs me. At first, I don’t know what to do with my arms. It’s the first time someone’s hugged me since Oma and Opa, at Christmas. I stand there, made out of elbows, while he bear-tackles me. But after a moment, I wrap myself around him. It’s a hug like warm cinnamon cake, and I sink into it.

And as I do, I sense that something deep inside me—something I didn’t even know existed anymore, after Jason—has woken up.