[Minus three hundred and eleven]

On Friday night, we eat fish and chips in the garden, straight from the paper, drinking ein prost! to Thomas’s arrival with mugs of tea.

I pick at scraps of batter, barely speaking except to say, “Please pass the ketchup,” until Papa drops the bookshop bomb on Thomas that he’ll be working Tuesdays and Thursdays. “Until your mother arrives. Oh, Ned,” he adds, “Gottie’s suggestion is you do Wednesdays and Fridays.”

Ned glares at me, and I say innocently, “I volunteered for Saturdays.”

I’m half hoping Ned will laugh and threaten some childish revenge, but our sibling simpatico is out of sync.

“Hmmm,” he says, before peppering Thomas with questions about the music scene in Toronto, naming nine thousand Canadian metal bands, and asking if Thomas has seen them play. The theme of the responses is no, and I get the sense Thomas isn’t half the scenester his T-shirts paint him as. Ned doesn’t mention the party.

Finally he runs off to Fingerband’s rehearsal in a cloud of hair spray. Papa floats off inside with a vague “Don’t stay up too late” and a reminder for Thomas to phone his mum.

Then it’s just me and him. It’s the first time we’ve been alone together since the squabble in the kitchen, two days ago. I refuse to apologize.

Twilight’s just gloaming and the bats are here, swooping in and out of the trees. Searching for bugs that haven’t yet arrived.

I scooch my knees up to my chin, wrap my arms round my legs, feeling gangly. After all of Ned’s chatter, the silence is palpable. When Thomas and I were little, we could not-talk over entire afternoons, side by side and fingers linked in a tree house or a pillow fort or a den, days that stretched on forever. Sort of the opposite of how me and Sof were. And we never had to check what the other was thinking, because we were telepathic.

I peek at Thomas, who’s holding scraps of fish in the air to make Umlaut play jumpy-jumpy. This is a terrible silence. He’s bored and wishes he were back in Toronto and hanging out with a girl who actually speaks. Someone cool. His insanely beautiful Canadian girlfriend, who he wants to call and tell all about his bizarro childhood pal.

The mosquitoes are beginning to bite when Thomas sneezes. And again. And again. “G,” he sniffles eventually, after an inhaler puff. “Evening pollen. Can we hang out inside?”

“Um, okay.” I stand up, attack of the fifty-foot woman while Thomas is still on the grass. Today’s cardigan is fuzzy and moss green. Then he unfolds himself too, a flash of flat stomach above his jeans. He turns towards the trees, not the house. Oh. He means hang out in my room.

“I’ve been wondering about this,” he says as we walk through the garden. “I wanted to ask all week—since when do you live in the annex?”

“Five years ago?” I say, as if it’s a question, holding back a bramble, thinking how the years he’s missed are the ones that matter. I got my first period and my first bra. I left school and had sex. I’ve been in love. I’ve made bad choices.

I’ve been to a funeral.

“About six months after you disappeared,” I explain, pointedly, “Ned was going through a farting stage. So Sof—my friend Sofía Petrakis, she moved to Holksea right after you left—made me march on the kitchen, waving a picket sign and demanding my rights. A-room-of-one’s-own, type thing.”

At the apple tree—which is now, thankfully, underwear-free—Thomas pauses, trying to twist early, unripe fruit from its gnarly branch. I lean against the trunk opposite him, the air between us fuzzy with gnats.

“Oh wow,” he says, peering up into the branches. “It’s there—”

Thomas yelps in surprise as the nascent apple finally comes away in his hand. The branch springs back, ricocheting us with flecks of ancient, lichen-sticky bark, and sending him staggering towards me. “Oops.”

He stuffs the apple in his cardigan pocket, then looks up at me and laughs. His face is spattered with gross tree grot. Mine must be too.

“Sorry,” he says, not sounding it. “I’ve given you bark freckles.”

Thomas’s real freckles, beneath the bark ones, are faint and translucent, like stars on a foggy night. He yanks his cardigan sleeve over his hand and lifts it to my cheek. I hold my breath. What happened under this tree five years ago, to make him go silent on me?

All the stars in the sky flicker out.

Literally. The only light in the garden is from the kitchen. There’s no moon, no stars, no reality.

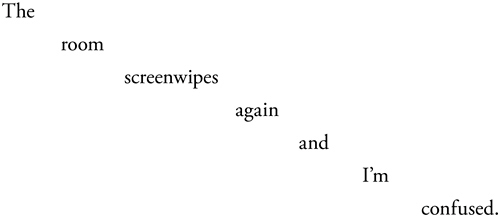

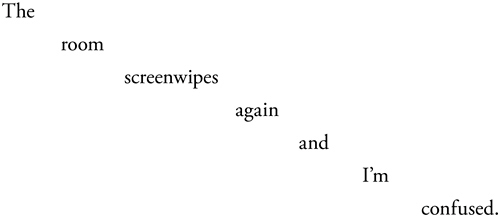

Thomas doesn’t notice. It’s as if we’re in two separate universes: for him, everything is normal. For me, the sky has gone blank. It’s a supersized screenwipe.

When he drops his hand, stepping away, all the stars ripple back. The whole thing only lasted for a moment—a fluorescent light on the fritz, spluttering in and out.

“There you go.” Thomas stares at me, confused. Maybe he did notice how the world just got a Ctrl+Alt+Del reboot. But all he says is, “You know, I was expecting you to have short hair.”

Whatever just happened, it definitely only happened to me. Or it happened to us both, but I’m the only one who saw it—we’re at opposite sides of the event horizon. The point of no return. I don’t want to think about which side I’m on.

* * *

“Whoa,” says Thomas, once we’re inside my room. “This is, as Grey would say, a trip.”

I scuttle to the bed. I’d forgotten about the emptiness. Thomas peers at what’s on my chest of drawers—hairbrush, deodorant, telescope. That’s it.

“Minimalist,” he says, prowling around.

It wasn’t always a monastery. When I moved in, Grey painted the floorboards, assembled a bed, and gave me a flashlight and the advice to never wear shoes when I cross the garden—“Feel the earth between your toes, Gottie, let it guide you.” (I always wore sneakers.) Papa gave me a twenty, which Sof commandeered to play interior decorator. I couldn’t stop her from buying cushions and Christmas lights, or putting stickers on my wardrobe.

When I cleared out the house last autumn, I got rid of almost everything in my room too. Made it negative space. It had felt cathartic. Now, seeing it through Thomas’s eyes and nothing on my corkboard but a handwritten school schedule, it just seems sad. There’s nothing to show that I’m here, that I exist. That this is where I live, breathe, don’t sleep.

“Where are the stars?” Thomas is turning in circles, looking at my ceiling, while I’m looking at him, and the way all the parts of him fit together. Arms and shoulders and chest.

“What?” I say, once I work out a response is required.

“On the ceiling.” He twists to look at me. “You always had stick-on stars. They glowed in the dark. Like magic.”

“Like zinc sulphide,” I correct.

“That was what I meant by the stars. You got all the references, right? In my email?”

This is the second mention of an email—and the second occasion it’s made time go flooey. I don’t get it. And even if he had my address, I don’t. I deleted everything, after Jason. And why would Thomas send me an email now, after five years? A warning of his surprise arrival? That means I should forgive him. But I’m committed to resentment.

I can’t screenwipe my brain into a new emotion.

Now Thomas is sitting on the bed, still gazing around as he shucks off his shoes. I’m a little weirded out by how at ease he is in my room. He picks up my clock from the windowsill and starts fiddling with it.

“What’s that?” he asks suddenly, pointing the clock at the equation on the wall.

“It’s math,” I explain. Then, duh, because it’s obviously math, I add, winningly, “An equation.”

“Huh.” Thomas drops the clock on the duvet and brushes past me as he shuffles on his knees to get a closer look. There’s a hole in his sock and I can see his skin. I was naked with Jason a dozen times, we even skinny-dipped, and this is just a toe, but it’s surprisingly intimate. “And this is on your wall, why?”

I reset my clock and nudge it back into place on the windowsill as Thomas flops around on the pillow end of the bed, getting settled.

“It’s homework.” That’s all I have to say—I don’t feel like explaining Ms. Adewunmi’s offer, I’m not even sure I want to take her up on it—but Thomas just impassively waits for more. “I’m supposed to come up with my own mathematical theory. I’m working on this idea that the time it takes to travel back and forth through a wormhole is less than the time an observer would spend waiting for you. You’d emerge late.”

“Reverse Narnia.” Thomas nods—the same conclusion I’d come to. Telepathy. “Okay. You were always Ms. Astronaut Science Girl Genius.” He nods at the telescope across the room, then looks around at the nothing else. “But what happened to your stuff?”

“I have stuff.” I’m instantly on the defensive. I point to Grey’s diaries, still stacked on my desk, and—ha!—“Look, see, there’s a cereal bowl on my chair.”

“Ooh, a bowl.” He waves his hands. “You need THINGS. My room’s like a monkey cage—plates, mugs. A Maple Leafs poster, cookbooks, Connect Four … I have postcards—all the places I haven’t been. Felt-tips, comics. You could walk in and immediately know, okay, this guy draws, he wants to travel, he likes Marvel more than DC, which tells you a lot.”

I gaze around my room, thinking, No, it doesn’t. It doesn’t tell me if you’ve ever been in love, or if you still don’t like tomatoes, or when you switched from sweatshirts to cardigans. It doesn’t tell me what happened when you left, or why you’re back. Then again, all I have are Grey’s diaries. Sof’s stickers. Other people’s things. Martians would be baffled.

“My room is a time capsule of me—” Thomas widens his eyes dramatically, stressing the words, as though I’m supposed to think, Oh, of course, a time capsule. Like the one he mentioned in the kitchen earlier this week.

“—of who I am right now,” he continues. “Thomas Matthew Althorpe, age seventeen. Archaeologists will conclude: he was messy.”

There’s silence again as I imagine him in Grey’s room now. Without all his things. Then Thomas pokes me with his holey sock and non sequiturs. “I poured whiskey on Grey’s carpet.”

“Wait—what? Why?”

“It was a ritual. A commemoration. That was his room, you know?”

“Yeah…”

“I didn’t think it through, where I’d sleep when I got here. Your dad gave me Grey’s room for the summer, and I didn’t want to act like it wasn’t a big deal,” he continues, “move in and take it over. It needed a ritual.”

“It needed whiskey?”

“Exactly.” He rolls up his cardigan sleeves and mimes pouring it out. I try to absorb this. That Thomas not only understands his being in Grey’s room is A Big Deal, he was thoughtful enough to do a supremely Grey-like thing about it, pouring whiskey on the carpet—equal parts superstition and ritual and mess.

“This is different—you coming back—than what I expected,” I admit to him.

“You thought I’d jabber aboot moose and maple syrup, eh.” Thomas dismisses the comment, rummaging for the apple and a handful of coins, piling them on the windowsill. “There,” he beams. “Grey’s room needed whiskey. Your room needs things. All the way from Canada. And, er, your garden. A time capsule of you: Margot Hella Oppenheimer, in her eighteenth summer.”

I feel a flicker of irritation. Those are his things, not mine—that’s not a time capsule of me. Mine would contain silence, lies, and regret, and I’d need a box the size of Jupiter.

“What is it with you and time capsules?”

“I like the idea of a permanent record,” he explains. “Something to say, This Is Who I Am, even when I’m not that person anymore. I left one back in Toronto.”

“What was in it?”

“Sharpies. Comics. My old glasses. A key ring for my car, which I had for all of two months before selling it to come here. I guess I don’t need it to escape my dad anymore, though. That’s Toronto. It’s like this—” He holds out his left hand, showing me the two-inch pink scar nestled there. “I’m not twelve anymore. We may not have talked for years”—he glances at me—“but I always had this, so I could remember that day.”

Whoa. His scar matches mine. I didn’t know he had one.

But it doesn’t mean he knows me.

“I don’t want to open our time capsule,” I say, not caring whether we really made one or not as my irritation gathers steam. “I don’t want to remember being twelve. Big deal, you have a scar too. That’s not a good enough reason never to write to me!”

Mum, Grey, Jason—none of them can answer me. It’s exhilarating, finally having someone to yell at.

Thomas hops off the bed and grabs his shoes. My words have slapped the dimples right off his face. His voice is flat as the landscape when he says, “Have you even considered it from the other way around? That you never wrote to me?”

After he stalks out the door, across the garden, the kitchen light stays on for hours.

I stay up with it. First I count the coins into neat stacks on the windowsill—they come to $4.99 exactly. Then I pick up my marker pen and draw a circle around the Minkowski equation, and write underneath:

WORMHOLES—TWO TIMES AT ONCE.

SCREENWIPES—TWO REALITIES AT ONCE.

And at the top of the wall, I write: The Gottie H. Oppenheimer Principle. v 1.0