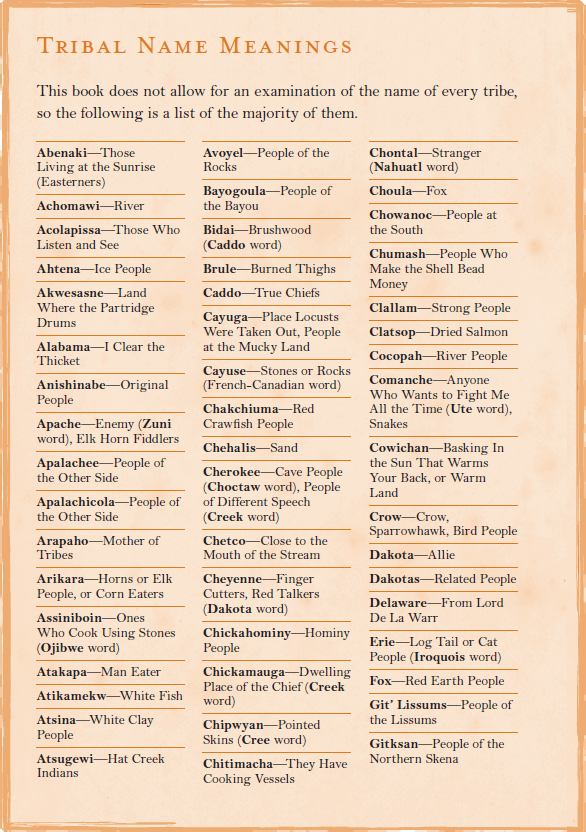

A chief of the Onondaga Nation whose name became synonymous with the concept of, and word for, “chief.” His dates of birth and death are not known; he lived prior to the founding of the Iroquois Confederacy in the 11th century.

Tadodaho has become the subject of myth. Accounts relate that this great chief had a twisted or disabled body and unruly hair; the origins of the word Tadodaho have a meaning akin to “entangled.” He also had a reputation for sorcery, reputedly being able to kill his enemies at great distances without even needing to see them. It’s not surprising, therefore, that Tadodaho’s rule was said to have been one of fear, a fear which extended beyond his own tribe to the Cayuga and Seneca peoples. In the years before the Iroquois Confederacy was founded, the initial five nations that founded it were constantly at war with one another.

It was the general fear of Tadodaho that caused delays in the peace process that was finally sealed with the founding of the Haudenosaunee. The chiefs of four of the five tribes of the Haudenosaunee were convinced that the only way forward was to put an end to the constant raids and attacks; Tadodaho, however, vehemently resisted the moves toward peace and thwarted at least three attempts by Hiawatha to get all the tribes to meet together amicably. Fear of Tadodaho was so entrenched that he was even blamed for the deaths of three of Hiawatha’s daughters: Hiawatha is reported to have accused Tadodaho of causing their deaths, before declaring that he would try to convince other tribes of the need for peace.

Further legends of the Haudenosaunee tell that Hiawatha and The Great Peacemaker, Dekanawida, like Tadodaho, eventually used magical and spiritual means to get Tadodaho’s support. Hiawatha and Dekanawida made a pilgrimage to see the chiefs of the Cayuga, Mohawk, Onondaga, and Oneida leaders, singing a song of peace as they traveled. They also convinced the Seneca people; only Tadodaho stood in the way. The pair sought the help of a Wise Woman known as Jigonhsasee to advise them on how to win over the recalcitrant chief. In a telling part of the tale, they use magic and the power of good spirits to soothe Tadodaho’s physical and mental pain, to heal him and calm him. In some accounts, Hiawatha combs Tadodaho’s hair while Dekanawida heals his twisted body. The outcome is that Tadodaho allows his people to join the great Confederacy; he himself becomes “firekeeper” and is appointed Chairman of the Council.

For the members of the Haudenosaunee, the name Tadodaho became synonymous with that of chief or spiritual leader, and is a title that is still in use today.

A sacred object belonging to the Kiowa people, generally kept among the precious items in what was known as “the sacred bundle.” The taime was a small stone model of a man, with a sun and crescent moon painted on his chest. He was decorated with downy feathers. The taime is said still to exist, and would have been shown once every year at the annual Sun Dance ceremony.

Also sometimes known as the “Rogue Indians,” along with other peoples who lived in southwestern Oregon, the “rogueish” behavior of the Takelma even lent itself to the name of the river that ran through their territory: the Rogue River. The Takelma belonged to the Penutian language family. The tribe lived in houses made of wooden planks, relied heavily on the crop of camas roots, and fished for salmon. Acorns were a valuable food source, too. The Takelma had two sorts of spiritual leaders: the shaman, who could both harm and heal, and the dreamers, who translated the messages and signs of the spirit world and kept evil influences at bay. Unusually, the Takelma also had women spiritual guides and leaders.

The Takelma gained their roguelike reputation because of their habit of attacking travelers in the area; the presence of non-Natives was deeply resented. This resentment exploded in the year-long Rogue River War that began in 1855 after some of the Takelma traveled to meet Captain Andrew J. Smith, who had hoped to make peace. Some of the men not under his jurisdiction attacked an Indian village, killing 23 elderly people and children. The Takelma therefore raided a white settlement and caused a further 27 deaths. The war raged all through the winter months until, in the spring of 1856, fresh troops arrived. The Takelma, under their chief Old John, made plans to surprise these troops with an ambush. Part of the plan was to send word to Smith that they wished to surrender. Accordingly, the captain took a brigade of 80 men to imprison the Indians. However, he was warned of the impending attack and waited, hidden, with his men. They held off the Takelma successfully and then a new consignment of soldiers arrived and the Indians retreated. Over the next few weeks, the remaining Takelma really did surrender and were sent to live on reservations. Old John was imprisoned for his part in the false ambush plot, and spent the next three years at the infamous island prison of Alcatraz.

Also known as the “speaker’s staff,” the talking stick is a simple but very effective device for ensuring democracy in tribal circles and in the tribal councils.

The stick itself is often elaborately carved, and can range from something that can be held in your hand to a much longer staff, not dissimilar to a small totem pole; in fact, the talking stick can sometimes be incorporated into a totem pole. The stick might be decorated with beads and feathers.

How does it work? In the Council Circle, the stick is passed from member to member. No one else may speak except the person holding the stick. This means that everyone has a chance to have their say. The holder of the stick may also allow others to comment. If one person is deemed by the rest to have held onto the stick and talked longer than is necessary, then force of opinion will move the stick along to the next person.

Sometimes a “talking feather” serves the same purpose. Any object designated can be used in the same way as the stick: a shell, a pipe, a string of beads, for example.

The simplicity—and fun—of the talking stick means that it has been adopted outside of Native American circles. It’s an especially effective tool for exuberant family dinners.

1628(?)–1698(?)

Also known as Tammany, and also as “The Affable One,” Tamanend was the chief of a Lenni Lenape clan. Evidently a peace-loving, friendly person, Tamanend played a key part in ensuring friendly relations between the existing Native Americans and the early English settlers who arrived with William Penn and subsequently established Pennsylvania.

Much of what we know about Tamanend is hearsay, and has almost become the stuff of legend. The first meeting between the two parties is said to have taken place under a huge elm tree at Shakamaxon, a Lenape village on the Delaware River. If Shakamaxon still existed it would be on the outskirts of modern-day Philadelphia. The tree itself blew down in a great storm in 1810, although the spot is now memorialized as Penn Treaty Park.

Tamanend was present at this meeting, and embraced the presence of the newcomers; it was reported that he said that the Indians and the white men would live peacefully together “… as long as the waters run in the rivers and creeks and as long as the stars and moon endure.”

After his death in around 1698, legends about Tamanend started to grow way beyond Philadelphia until he achieved the status of a folk hero, an unofficial “saint” of North America.

The first Tammany Society started in Philadelphia in 1772, though perhaps the best-known of the many such societies that sprang up is the one called Tammany Hall that was established in New York in 1786.

?–1853

Tanaya was a chief of the Yosemite Valley Indians, known as the Awahnichi (the Native American name for the Yosemite Valley). This tribe was a part of the Mono people, which in turn were a part of the Paiute people. The name Yosemite was given the Awahnichi by surrounding tribes; they were evidently a ferocious people, because Yosemite means “killers.”

When the Awahnichi were decimated by a virulent disease, the survivors left their homelands, seeking refuge with the Mono Paiutes. Here Tanaya’s father met and married a Mono woman, and Tanaya was born. He also married a Mono woman, with whom he had three children.

When he was 50, a medicine man advised him to return to the Yosemite Valley; the illness there, said the medicine man, was gone. Accordingly, Tanaya returned with some 200 of his people.

In the early 1850s the relationship between the white settlers—many of whom were prospectors—and the Natives was at breaking point, and the U.S. Government decided life would be easier if the Indians were dispatched to reservations. Tanaya agreed to the move, knowing that the alternative could be the entire destruction of his people. Unhappy, his people soon decided to leave the reservation, but the U.S. Army returned to round up the Indians and Tanaya’s youngest son was killed.

There are different accounts of Tanaya’s death. It’s possible that he was killed in a fight while gambling; other accounts say he was stoned to death by a group of Mono Paiutes after stealing some horses.

1742–1818

Born close to what is now Detroit, Michigan, Tarhe belonged to the Wyandot tribe. His nickname was “The Crane”—which, it is supposed, was due to his tall, slim shape.

In common with other Native Americans, Tarhe was very unhappy about the continual encroachment of the white settlers onto Indian territory, and wanted to prevent any further incursions. The colonists didn’t heed any advice or instruction; although an edict from the British Government in 1763 specifically told the colonists that the land to the west of the Appalachian Mountains belonged to the Indians and that they should not go there. This ruling was ignored, and settlers continued to trespass, with the result that skirmishes and fights between the two parties increased in intensity until, in 1774 John Murray, the Governor of Virginia, amassed troops to attack the Natives. Tarhe played a part in the battle, but the colonists overpowered the Indians and won the fight.

Tarhe, like others, wanted an end to the fighting but was forced to lead his people into battle once more. The Battle of Fallen Timbers saw the Native American defeated yet again. Tarhe once again advocated for peace, resisting further attempts from leaders such as Tecumseh to continue to attack the settlers.

In his seventies, Tarhe fought on behalf of the Americans in the American Revolutionary War. Afterward, he lived a peaceful life in the Upper Sandusky area of Ohio, and died in 1818.

“ … the only way to stop this evil, is for all the red men to unite in claiming a common and equal right in the land as it was at first, and should be now—for it never was divided, but belongs to all … Sell a country! Why not sell the air, the clouds and the great sea, as well as the earth? Did not the Great Spirit make them all for the use of his children?”

—Tecumseh to

William Henry Harrison, 1810

One of the greatest leaders of the Shawnee Nation, Tecumseh—also known as “Shooting Star” or “Panther Crossing”—was born in or around 1768 in Ohio, one of eight children. Tecumseh’s birth was accompanied by a great meteor, and his tribe believed from early on that this star carried with it a message: that this baby would grow to become a great and important leader.

His father died in battle in 1774 when Tecumseh was just six years old; this must have shaped Tecumseh’s attitude toward the U.S. Army. The Shawnee territory, like that of most other Native Americans, was gradually being encroached upon by the white settlers, and when Tecumseh was 11 his mother moved away, probably with others of her tribe, heading toward Missouri. Tecumseh stayed behind with his sister Tecumpease and his older brother Chiksika, who raised him.

Chiksika was responsible for training his little brother in the arts of war. Tecumseh had an opportunity to find out what a battle was all about when he was just 14. A U.S. Army troop was led into battle in Ohio and the young Tecumseh was panic-stricken, reduced to running away from the battlefield. After this somewhat humiliating experience for a young warrior, Tecumseh vowed never to run away from anything ever again. Evidently his fear abated and his courage increased until he was accepted as a trusted leader of the Shawnee tribe.

Tecumseh’s passion was that the white men should not be allowed to take Indian lands; if they tried, they should be met with violence. In 1794, at the Battle of Fallen Timbers, a confederation of Native Americans which numbered Tecumseh among their ranks were defeated by the U.S. Army led by Antony Wayne. At this time many Natives believed that the only way they could appease the white men was to give up their inherited lands; Tecumseh opposed this defeatism. When the Treaty of Greenville was accepted in 1795, its conditions included that land in the northwest of what is now Ohio be ceded to the settlers. Tecumseh was among those who opposed the signing of the treaty.

Tecumseh took the view that no single tribe could own land; the land, he argued, belonged to all Native Americans. He also proposed that the best way to oppose the white men would be for the Indians to join forces—in short, to become a confederacy. He posited these ideas at the very early part of the 19th century, and visited as many of the tribes as he could that were living west of the Appalachian Mountains between Canada and the Gulf of Mexico, trying to persuade them to join the confederacy. He was accompanied in this quest by his younger brother Tenkswatawa, who was also known as “The Prophet.”

Tenkswatawa had had a vision. The Shawnee Indians’ primary god, The Master of Life, had appeared to him and told him that the Natives had offended their god by adopting the customs, habits, and products of the white man, and that they should return to their own ways to make amends. Many Native Americans obeyed the words of their prophet and turned their backs on European introductions such as guns, iron equipment, and, of course, alcohol. They also rejected the Christian practices that the white settlers were so keen to superimpose on the Native peoples. Movement in favor of Tecumseh increased, and many Indians traveled to Prophetstown, which the two brothers had established in 1808.

In 1810, Tecumseh met with the governor of the Indian Territory, one William Henry Harrison, who would later become U.S. President. A fine orator, Tecumseh eloquently presented the case that the Indian territories should be returned to the Native peoples. The result of his stirring speech was that the diplomatic meeting nearly ended in violence.

This gathering of the tribes in Prophetstown did not go unnoticed by the U.S. Government, and in 1811, at a time when Tecumseh was away visiting other tribes which he wanted to persuade to join the confederacy, Harrison led an army toward the village. Here, a great tragedy occurred. Although Tecumseh had ordered his brother not to attack any Americans should they appear, since he knew that the Indians would stand no chance against the militia, Tenkswatawa had received another vision from the Master of Life, who had decreed that none of the Indians under his care could be harmed by the white army’s bullets. So Tenkswatawa ignored his brother’s advice. The Indians quickly realized that Tenkswatawa’s information was incorrect. They were forced to run away, and retreated into the woods. The Battle of Prophetstown resulted in the town being destroyed, burned to the ground, with a great loss of lives on both sides—although, perhaps surprisingly, the greater number of deaths were on the Army side. The Shawnee were subsequently defeated conclusively by Harrison at The Battle of Tippecanoe.

Tecumseh lost many of his friends, and his idea of a confederacy was seriously damaged. Tenkswatawa, further, was dismissed as a faker, and Tecumseh must have borne the brunt of this, too.

Tecumseh was killed at the Battle of the Thames, close to what is now known as Detroit, fighting on behalf of the British. Forces under the direction of Harrison were responsible for Tecumseh’s death, although Tecumseh had been made a Brigadier General and was in charge of some 2,000 warriors made up of allied tribes that were kindly disposed toward the British.

A further legend about Tecumseh was that he foresaw his own death; wanting to die as an Indian, on the day of the fatal battle he had removed his uniform and reverted back to his buckskin clothes.

Above all, perhaps, it was Tecumseh’s attempt to gather together the Native American forces that is the most notable part of his legacy. Such was the respect for this Shawnee chief that a prominent general in the Civil War, William Tecumseh Sherman, was named after him.

A more curious aspect to Tecumseh’s legacy is a curse that came to be associated with him. President Harrison died just a month into office after delivering a very lengthy inauguration address out in freezing January weather; subsequently, every president elected in a year that ended in zero died in office—though only up to the president elected in 1960, John F. Kennedy. The men elected president in 1980 and 2000—Ronald Reagan and George W. Bush, respectively—did not fall victim to this alleged curse.

c.1775–c.1836

Lalawethika was the original name of the Shawnee prophet who was the brother of the great leader Tecumseh. He was born near Springfield, Ohio.

In 1805 Lalawethika had a powerful vision that his people should reject the ways of the Europeans and reclaim the Native American way of life and spirituality. Further, he believed that Indians should unite in their aim of repelling the advance of the Europeans, forming a confederacy which would have strength in both numbers and in their aims. Lalawethika also correctly predicted a solar eclipse, which gave him a great deal of credibility.

After his vision, Lalawethika changed his name to Tenkswatawa, meaning “The Open Door.” One of his earliest followers was his brother, Tecumseh, who saw the sense in what Tenkswatawa was advocating. In 1808 the brothers founded a settlement, Prophetstown, at Tippecanoe Creek in the Indiana Territory. People flocked to hear Tenkswatawa’s message, but in 1811, while Tecumseh was away, the village was razed to the ground by Governor William Henry Harrison and a force of approximately 1,000 men. Tenkswatawa had predicted that the white men would be defeated; the outcome meant that he was discredited. He moved away from the area to Canada. In 1826 he returned to Ohio and subsequently relocated, with the rest of the Shawnee people, to the Indian Territory in Oklahoma. He died in or around 1836, in Kansas.

Meaning “dwellers on the prairie” in their own Siouxan dialect, the Teton are the main division of the Dakota/Lakota branch of the Sioux tribe. The Teton were further subdivided into the Blackfeet, Brule, Hunkpapa, Miniconjou, Oglala, Sans Arc, and Two Kettle.

Not restricted to the Founding Fathers by any means, the Native Americans of many tribes, including the Iroquois Confederacy, had a number of different ceremonies whose purpose was to express gratitude toward the Great Spirit. These included a midwinter thanksgiving, giving thanks for the crops of strawberries and raspberries, a maple-or sugar-making thanksgiving, a number of thanksgiving ceremonies centered around corn (planting it, hoeing it, celebrating the green corn and the ripe), and a harvest thanksgiving.

In the fall of 1621, an event took place which would become entrenched in America’s culture. The first Thanksgiving took place as a celebration of the Pilgrims’ survival of the previous year’s terrible winter, due in no small part to Tisquantum, a native of the Patuxet tribe, who had not only acted as interpreter for the group but had taught them how to grow corn and how to catch eels, as well as other methods of survival. The leader of the Wampanoag tribe, Massasoit, had also given the Pilgrims enough food to make up for the fact that their own supplies proved to be insufficient.

This first celebration took place immediately after the harvest had been safely gathered in, and at the time held no more significance beyond being a typical harvest supper; the Wampanoag celebrated the harvest in much the same way. Poignantly, the celebration took place at the place where the Patuxet had lived until the entire tribe—except for Tisquantum—were obliterated by smallpox between the years 1616 and 1620.

The white settlers sat down to the feast with the Native Americans of the area, including Massasoit and Tisquantum. Massasoit was accompanied by a retinue of approximately 90 men.

Accounts from the time give us some detail as to the menu. This included enough fowl to feed the entire party for a week, and five whole deer.

This first Thanksgiving became a symbol of cooperation between the Native Americans and the settlers, an ideal which would soon be shattered. Subsequent settler colonies had thanksgiving feasts, too, although they did not all fall on the same day. It wasn’t until 1863, in the midst of the Civil War, that President Abraham Lincoln declared that a unified Thanksgiving Day should be held every November.

1888–1953

Born James Francis in Oklahoma in 1888, Jim Thorpe would become one of the most famous Native Americans, with a reputation for being one of the greatest athletes who ever lived.

A member of the Sauk, Jim’s Native name, Wathohuck, translates as “Bright Path.” His mother—whose antecedents included the Sauk and Fox chief, Black Hawk—gave birth to Jim and his twin brother in a lowly one-roomed shack in Oklahoma. His brother died when they were eight years old, and Jim was sent to be educated at the notorious Carlisle School in Pennsylvania a year later. He played halfback on the school football team.

When he was 24, Jim participated in the Stockholm Olympics. Here he won gold medals in the decathlon and pentathlon, proving his all-round athletic capabilities. He set records in these events that would remain unbroken for 20 years. A year later it emerged that Jim had played a little semi-professional football; in the eyes of the Olympic Committee this meant that he was a professional athlete instead of an amateur. Jim was stripped of his medals, to much outrage.

Jim went on to play for the New York Giants baseball team and also played professional football. Jim Thorpe died in 1953 at the age of just 64; a town was named after him, a granite tomb dedicated to his memory, and the gold medals were reinstated 20 years after his death.

A confederation of the Hidatsa, Mandan, and Arikara Nations, whose original territory extended across the basin of the Missouri River in the Dakotas.

Also known as the Council of Three Fires, this was a confederacy of the Ojibwe, the Ottawa and the Potawatomi tribes. The Ojibwe were the “elder brother” and described as the “people of the faith”; the Ottawa the “middle brother” and the “keepers of trade”; the Potawatomi were the “younger brother” and the “keepers of the fire” (which is actually the meaning of the name Potawatomi).

A mythological bird of colossal size, which the Native Americans believed was the creator of thunder and lightning. The Plains Indians thought of the creature as an actual bird, whereas other tribes—particularly those in the northwest—envisioned it as a giant human being who had donned the costume of a bird, replete with wings which made the giant actually able to fly.

Every aspect of a storm was explained by the actions of the Thunderbird: thunder was the flapping of its wings; the storm cloud was caused by its approaching shadow. Its blinking eye caused lightning. And rain poured down from the lake carried by the bird upon its back.

The stylized form of the mystical bird is a popular design, often seen on clothes or moccasins. In picture writing, the bird has jagged arrows, representing lightning, coming from its heart. The Thunderbird symbols of the Arapaho and Cheyenne are shown grasping these arrows in their claws. The eagle depicted on U.S. coins and dollar bills was recognized by Indians as the Thunderbird and they named it “Baa,” their appellation for the Thunderbird.

The Thunderbird, according to myth, dwelt on a high mountain or promontory; there are place-names within the landscape which bear testimony to this legend, such as Thunder Bay at Lake Huron, Michigan.

Native American peoples did not observe the passing of time and the seasons using a calendar in the same way that the white settlers did, but instead marked time out in a different way, using notches along a stick of wood, or knots made in a length of rope. Also, elaborate and detailed pictures were painted onto hides, which charted the passage of time; these hides are known as the “calendars” that belonged to the Dakota and Kiowa tribes. Of these, the most famous is the Dakotan painted hide known as the “Lone-Dog Winter Count,” which charts significant events between the years 1800 and 1871. “Winter” is the term that was used to describe the full course of a year. Indians did not keep a tally of how many winters they had lived through to determine how old they were in years.

A year was counted by the number of moons; a new month began with the new moon, hence the mention of “moons” to describe the passage of time. Some tribes used a system of 13 moons to one “winter,” others preferred 12.

There were no rules about exactly when a year started. Some tribes preferred to count from the spring, and others from the fall.

Each “winter” had four seasons, described by the action of plants: budding, blooming, leafing, and fruiting, and by the actions of animals and birds.

Like the year, the day, too, was segmented into four periods. These were the rising of the sun, noon, the setting of the sun, and midnight. One full day was referred to as a “sleep,” or night.

Any owner of the latest bell tent will be gratified to know that its design is based on an earlier tent, the Sibley Tent, named for General Henry Hastings Sibley. The General based his tent, in turn, on the design of the tipi, the traditional dwelling place of the Plains Indians.

The word is from the Dakota: tipi (sometimes spelled teepee), means “the place where one lives.” As tents go, the tipi is ultimately roomy, comfortable, and relatively portable. Modern tipis are made from wooden poles and canvas; the traditional ones were made from between 15 and 18 prepared buffalo hides, cut and stitched together to make a large semi-circular sheet. Then there were any number of poles, from 13 to 23.

Erecting the tipi was the role of the women of the tribe, and the method has not changed. First, three poles are lashed together a few feet from the top of each pole, and spaced to form a sturdy tripod. One of the poles faces East and forms the side where the entrance to the tipi will be located. Then the rest of the poles—whose number depends on the final size envisioned for the dwelling—are leaned up against the tripod until all the poles are evenly spaced, describing an ovaloid on the ground. The last pole has the hide or canvas covering tied to it, and is placed in position at the back of the tipi. The covering is then wrapped around the poles. The edges of the covering are woven together using wooden sticks slotted through holes in the hide.

The door is a flap made from a separate piece of skin. Finally, two further poles are slotted into loops on either side of another flap at the top of the semicircle of fabric. These poles operate the flap to direct smoke from the fireplace out the top. The bottom edge of the tipi is secured to the ground all the way around, using pegs.

The tipi was designed to be both erected, and dismantled, quickly and efficiently, since the Plains peoples survived by following migrating herds of buffalo. It was said that an entire community could be packed and ready to go in one hour.

The tipi itself, like other Native American dwelling places, was considered to be sacred space, a model of the universe in microcosm. Therefore there was a degree of ritual and tradition associated with the placing of everything inside.

The existing circles of stones that were once used to hold down the hide covering of the tipi. There are thousands of such stone circles still in existence.

Tisquantum is generally referred to by his nickname, Squanto. Historical records list the year of his birth as 1580, although this might not be accurate. He died in 1622.

Squanto belonged to the Patuxet tribe, and the area in which he was born and spent his formative years became Plymouth. He is famed for the assistance he gave to the early Mayflower pilgrims, who suffered badly after their first winter in the “New World.” If not for Squanto, it’s unlikely that any of the party would have survived—and if that had been the case, the course of history would have been dramatically different.

Not much is known about Squanto’s early life. He comes under the spotlight when the English arrive in North America. As well as plundering the land and stealing crops and animals from the Native Americans, there was another, even more sinister aspect to the English exploitation of these people: the slave trade.

Squanto nearly fell foul of the burgeoning slave industry when he was kidnapped by Thomas Hunt, a lieutenant of the infamous Captain John Smith (he whose life had allegedly been saved by Pocahontas). Hunt lured some two dozen natives on board his ship under the pretext of trading beaver skins, which was a lucrative business for both parties. The plan was that Squanto would be sold as a slave, along with several others, for around £20 per head (the equivalent of $4,500 today). They were taken to Malaga, in southern Spain, but once there Squanto was among a number of captives who were relatively fortunate enough to end up in the care of the local Catholic friars, who sought to convert the “heathens” to Christianity. Back in North America, the incident outraged the Patuxet and Nauset tribes, and Hunt’s actions conclusively ended the profitable trade in beaver skins for those tribes.

Not long after this, in 1618 and 1619, the tribes’ problems would become worse than ever when the entire community at Patuxet was wiped out by a horrendous plague. The cause of the plague was never determined, but it could have been smallpox, tuberculosis, or, most likely, leptospirosis; the Indian natives had no immunity whatsoever to diseases carried by the new settlers.

Squanto, although he was unaware of this at the time, still being in Spain, was the only surviving member of his tribe. He found himself voyaging from Malaga to London, to the home of one John Slaney of Cornhill. Here, Squanto’s grasp of the English language improved, with the result that he was able to act as an interpreter for Slaney, who, as treasurer of the Newfoundland Company, needed a person with such bilingual skills since the Company had colonized a place called Cupper’s Cove, Newfoundland, in 1610. Squanto was duly sent off to Newfoundland, where he worked with the Governor of this new colony.

The rift between the white men and the Native Americans caused by the kidnapping of Patuxet and Nauset men had never been healed. This meant that the formerly lucrative beaver trade had pretty much come to a halt. But one man had other ideas: Thomas Dermer, employed by the New England Company, was a ship’s captain who had worked with John Smith in the past, and maintained hopes of reviving the trade. In Tisquantum, he saw a man who might be able to heal the rift between the Indians and the English: Tisquantum’s bilingual skills, and the fact that he was Patuxet yet had good relationships with the English, all pointed in the right direction.

So Squanto was on the move once more. He and Dermer headed off back to New England in 1619, to make peace with the Natives and revive the beaver trade. Imagine the shock that Squanto must have felt when he discovered that all his people had died of the plague. The Patuxet people had been part of the Wampanoag Confederation, so Squanto made contact with the head of the Confederation, Massasoit, and his brother Quadequina, with whom he stayed. Unable to make peace with the Patuxet because they in fact no longer existed, Dermer wanted to persevere instead with the Nauset tribe. However, he was captured by them, presumably as a form of revenge for the earlier actions of Thomas Hunt. Squanto negotiated Dermer’s release, although it was only a little later that the captain was attacked once more as he continued south, and died of the wounds he had suffered at Martha’s Vineyard once he reached Jamestown in Virginia.

And the attacks on the English didn’t end there. The Mayflower pilgrims had arrived in Provincetown Harbour in 1620, and sent three parties out to get the lay of the land. Although the third of these parties was attacked by the Nauset, no one was hurt and these pilgrims eventually settled in the territory that had once belonged to the now-obliterated Patuxet. The area had already been renamed Plymouth by John Smith in 1614.

The pilgrims had essentially lived on board the Mayflower while they built their houses and stores on land. They worked from December onward, and decided that it was time to come to shore properly in March of 1621. They had had no encounters with the Natives during all this time, and presumably thought they had chosen their new home well. Then on March 16, a real live Native appeared in their midst: Samoset, who had picked up some English from the fishermen in Maine, introduced himself and told them about Tisquantum. Squanto visited a few days later with Massasoit and Quadequina. Both parties took the opportunity to extend the hand of friendship. Squanto essentially rescued the Pilgrim Fathers over the course of their first winter on the land, which was harsh, by teaching them two things: the cultivation of maize, and the use of fish as a crop fertilizer. Tisquantum’s role within the Plymouth colony was absolutely essential. Ultimately, however, Squanto would come to be viewed with some distrust by both the English settlers and his own people.

It’s likely that Squanto, realizing the situation he was in, began to use what he knew about both the settlers and the Native Americans to his own advantage. For example, he would have known that the Indians would have a great fear of the English guns and other weaponry, and also their unknown “plagues” and other infections. Squanto would promise to “put in a word” for his own private benefit.

Massasoit retaliated by ordering the Pilgrims to turn Squanto over to him, so that he could be tried and punished—presumably by death. Although the terms of their peace agreement dictated that they should obey this demand, the Pilgrims also knew that Squanto was essential to their survival and success. Squanto was about to be turned over to his own people when he had a great stroke of luck: a ship appeared on the horizon, and his own immediate dilemma was abandoned in the eagerness of both parties to identify the vessel.

Ultimately, though, it didn’t matter that Squanto remained a free man. In 1622 he came down with an unknown fever—a fate which would meet many Indian natives, including Pocahontas. The first sign of his imminent death was a bleeding nose, and Squanto knew immediately that his days were numbered. He died shortly afterward, after allegedly praying that he might find himself in the Englishman’s Heaven, rather than that of his own people.

A beer, made by the Apache among others, consisting of the pressed juices of green corn sprouts. The juice was then boiled.

This tribe were situated in the Pacific Northwest, including the islands of Alaska. Tlingit—which is their own name for themselves—means “The People of the Tides.” The Tlingit, given their location, became highly skilled fishermen and sailors, and built huge dugout canoes, some as long as 60 feet. They lived in wooden houses, and most famously were the original totem pole builders. Iron tools brought by the white settlers became a key instrument in fashioning these highly-decorated poles, which stood in front of each house. The potlatch ceremony, adopted by other tribes, also originated with the Tlingit; although wealth and power were considered to be important, equally important as status symbols were generosity and moral principles, all of which formed the spirit of the potlatch. The art of the Tlingit people—very distinctive, quite modern-looking animal and bird images in bold, blocky colors—is interwoven with their spirituality and history. In common with some other Native American peoples, the Tlingit are a matrilinear society.

The Tlingit are divided into two “families”: the Raven and the Eagle. These two are further divided down into subgroups that identify themselves with crests which look somewhat like Western-style heraldic devices, and appear on their totem poles and also in weavings, jewelry, canoes, etc.

Relatively speaking, the Tlingit and the Europeans did not meet until fairly late, when Russian explorers “discovered” them in 1741. The Spanish explorers followed in 1775. Although the Tlingit managed to retain their independence and never had any huge wars or battles with the settlers, unfortunately the coming of the white man brought disease, including smallpox; the first outbreak of this was severe enough to reduce many of the Tlingit to adopting Christianity when the cures offered by their own shaman failed to prove effective. To help promote the new religion, Russian Orthodox missionaries had their texts translated into the Tlingit tongue. Prior to this, the shaman had been a key figure for the Tlingit, seen as being able to influence the chances of a successful hunt, alter the weather, cure diseases, and predict the future.

Food is an important and central feature of the Tlingit cultural identity, and they are fortunate in that food is abundant and varied in their part of North America. Salmon is possibly the most important food, closely followed by seal (which also provide skins), and other game. Sea otters, fish, and shellfish are also abundant. Inland, animals such as deer and bear are supplemented with berries and other fruits. Although it would be possible to live “off the beach,” The Element Encyclopedia of Native Americans this is considered to be taboo; men going into battle would never eat from this source, and shamen believed that to do so would sap their spiritual powers.

The effigy of a Native American, often resplendent with feathered warbonnet, is still used as an advertising logo for outlets selling tobacco. This is because it was the Native American who effectively gifted tobacco to the world. Columbus was offered tobacco as a goodwill gesture, and later observed the Indians smoking the herb in the form of cigars.

As a sacred herb, tobacco is used to make offerings to the spirits, to the six directions of north, east, south, west, above, and below, and the elements; a pinch could be used to sign a treaty or to assist in the cure of an ailment. Although tobacco was smoked purely for pleasure by Native Americans, its primary use was as a sacred ceremonial herb. It was very rarely taken “neat,” but would be mixed up with other herbs—whatever was at hand in the locality. This smoking mix is called kinnikinnick.

Soon tobacco was cultivated by the Europeans, who, ironically enough, sold their tobacco—compressed into cakes—back to the Native Americans. This processed tobacco was not considered suitable for sacred or ceremonial use.

It’s astonishing to remember that in fewer than 100 years after it was introduced to the white man, tobacco had grown so popular that its use had spread throughout the entire world. The first places in Europe to have it were Portugal and Spain, in 1518; France was introduced to it in 1559 by Jean Nicot (hence the word “nicotine”), and by the early 1600s its use had spread as far as what is now Alaska.

Originally a Powhatan/Algonquian word, the tomahawk (from the words tomahack, tommahick, tamahake, or tamahaac) is an ax-like instrument that was at first used more often as a weapon than as a tool. The “hawk” looks a little like a hatchet; the shaft is about 2 feet in length and is made of a hardwood such as hickory. The “head” can weigh anywhere between 9 and 20 ounces, with a cutting edge of about 4 inches long. The sharp end of the tomahawk is usually made of metal these days, although they used to be made of carved stone. Carved soapstone tomahawks have a ritualistic rather than aggressive use, since soapstone is too soft to have much impact.

We often think of the tomahawk as having a pipe bowl at the end opposite the blade, but in fact such instruments were often actually made by the English and then sold back to the Native Americans. They were created by the Europeans as objects to barter, and often given as gifts; symbolically, the “pipe tomahawk” displayed the capabilities of both war and peace.

As a good general purpose tool, the tomahawk was also adopted by the white settlers. Today the instrument is used in the sport of tomahawk throwing, carried out by historical re-enactment groups. There’s also a branch of martial arts, Okichitaw, which has revived the tomahawk fighting practices common during Colonial America times.

1644–1739

Although many details of Tomochichi’s life have been lost, we do know that he was an important leader of the Creek tribe, living in a town that stood in the place now known as Savannah, Georgia.

Exiled from the Creek for reasons which are not known, he settled with his followers in Savannah. We do know that he established his own band from the Creek and Yamasee peoples, named the Yamacraws, and this following numbered some 200 or so people.

In 1733 a group of prospective settlers arrived in the area. Their leader, General James Oglethorpe, knew that he would need the assistance of the Indians in the area if they wished to establish themselves there. Luckily, he had the advantage of a translator, one Mary Musgrove, who had had a Creek mother and an English father. Tomochichi was well-disposed toward the settlers and gave them permission to stay. In fact, Tomochichi would become known for his helpfulness to the early settlers, helping them as mediator in their negotiations with other tribes to the point where he was even taken to England as part of a delegation, when he had the chance to present King George II with eagle feathers, as a tribute and as a symbol of peace.

It’s likely that Tomochichi realized that a friendly approach to the white men would enable him to negotiate successfully on behalf of his own people. Tomochichi believed that education was a powerful tool, thought the Christian faith would be good for the tribe, and so worked with the settlers in founding an Indian School in 1736, although the idea was initially rebuffed when he met with Charles Wesley, the leader of the Methodist movement.

This great chief died in 1739. The colonists gave him a public, Christian funeral ceremony in honor of the large part he had played in establishing their colony.

The presiding spirit of either an individual or a tribe, the word “totem” comes from the Ojibwe word ototeman or odoomen, meaning “his sister-brother kin.” This gives us an indication about the deeper meanings of this word.

Many Native Americans—and others, now, who have followed suit—hold that our spiritual “ancestors” are not simply human but also nonhuman, or maybe a hybrid of the two, and that we hold within ourselves the spirit, power, characteristics, and knowledge of these animals or birds. The idea of an animal “belonging” to a particular family is similar to the idea behind heraldic devices as used in other parts of the world. Popular totem animals among Native American peoples include the wolf, bear, turtle, fox, beaver, eagle, raven, and owl. The totem also acted as a guide and protector, and it was taboo for living manifestations of the totem to be hunted, killed, or eaten.

The totem animal might appear to its human counterpart either after a real encounter in the physical world, or as a result of a vision in the Otherworld. Tribal divisions were often named after their animal affiliations: for example, the Bear Clan, the Wolf Clan.

Today, a totem animal is sometimes referred to as a “power animal,” and this idea extends beyond the Native American spiritual belief system. An individual might have several different power animals, the characteristics of each being accepted as a kind of inner “tool box” which the possessor can call upon whenever those skills are needed: the cunning of the fox, the wisdom of the owl, the ferocity of the tiger.

Totem poles are primarily the province of Native Americans living in the Pacific Northwest. Because the poles are made of wood, and wood decays fairly quickly in rainy and wet environments, it’s hard to say definitively just how long the totem pole has been a tradition. Poles that pre-date 1900 are hard to come by. As a cultural icon, however, the totem pole is synonymous with Native American culture. And accounts from explorers tell us that totem poles must have existed at least prior to 1800.

The word itself, totem, comes from an Ojibwe word, “odoodem,” meaning “kinship group.” (The same applies to the idea of the totem animal, an animal with which we feel a great affinity, also known as the power animal.)

We can only imagine what those early explorers would have made of the totem pole the first time they ever saw one. It’s possible that the poles are extrapolations of earlier carved interior house posts, and that the first people to make this innovation were the Haida, with others such as the Tlingit emulating these huge carved objects. There are different styles across different tribal groups—a sort of totem pole vernacular, as it were.

It also seems that the totem pole is one aspect of Native American culture that was actually enhanced by the coming of the European white men. The sharp metal tools belonging to the settlers were ideal for carving into the huge chunks of redwood. Additionally, the fur trade between the tribespeople and the white settlers brought a great deal of wealth to those tribes. This meant that the potlatch—a large gathering—became more frequent and more elaborate. Specially designed totem poles were often erected at these gatherings.

But what was the totem pole for? What was its purpose and function?

First and foremost, the pole was a symbol of status, not only of the wealth of the tribe, but of its social status and importance. Each pole would be carved with figures and effigies that were important to a given family; each totem pole is totally different from the next. They might tell the story of the tribe and have carvings depicting the ancestors, relevant animals, or notable events. These events might range from the ridiculous to the sublime: debts, thievery, family feuds, legendary shamanic powers. Certain parts of totem poles might include grave boxes or other funereal artifacts. In a way, a totem pole is a kind of flag for the tribe or the individual to whom it belongs.

Although totem poles were never used as objects of worship, and would often be left to rot if their owners had to move away, the Christian settlers of the 19th century dismissed the beautiful poles as objects of heathen worship, and where the poles had started to proliferate, their creation was now discouraged. There was a resurgence in pole construction in the middle of the 20th century as part of the revival of interest in Native American life and culture. Poles—pale in color because they are so freshly carved—can be found along the length of the Pacific Northwest coastline. A profitable side-line is the manufacture of miniature totem pole trinkets for the tourist trade.

The resurgence of the totem pole has provided a new industry, with established artists taking on apprentices to teach them this ancient art. If you want to commission a pole, this can cost thousands of dollars, and each pole takes about a year or so to execute.

The carved effigies on the totem pole are—incorrectly—believed to follow a hierarchical ordering, with the least important placed at the bottom, i.e. closer to the earth, and the highest at the top, nearest the sky. In fact, this isn’t the case at all; the figures can be in any order, and often appear to be configured randomly.

There’s another kind of totem pole which has a different use and meaning. These are “shame poles,” purposely made to humiliate an individual or a group of people who have unpaid debts. The original reasons for the placement of these poles are often long since forgotten, but there is one particularly important “shame pole” in Saxman, Alaska. The story goes that it was constructed to try to shame the then-U.S. Secretary of State for not hosting a reciprocal potlatch for the Tlingit tribe. The effigy of the man in question has his ears and nose picked out in red, to indicate his stinginess. There’s another such pole in Wrangell, Alaska, known as the “three frogs” pole. Three of the Kiksadi clan impregnated three young women of Chief Shakes’ clan, and the pole was erected to try to shame the young men into paying to support their children. This never happened, and the pole—featuring three frogs, one atop the other—still stands outside the house of the Shakes’ chief. The frogs are a crest of the Kiksadi clan, but the white settlers—having no idea of its meaning—used it as the motif for the town; it even appears on the masthead of the local newspaper.

Modern tools might be used to carve totem poles these days, but despite this, the poles are always erected in the time-honored way, with much ritual and ceremony. First, a huge set of wooden scaffolding is constructed, and then lots of big, strong men—sometimes hundreds of them, depending on the size of the pole—gather to haul the pole vertically into its base. Other men steady the pole from the sides and brace it. Once in place, the celebrations or the potlatch can begin, and the carver and his team are given due thanks and honor. The carver of the pole will usually perform a dance around it. The base of the pole is scorched with fire to try to make it a little more resistant to rot.

Other than this scorching there seems to be very little effort made indeed in the way of maintenance. A pole will last for about 100 years before the signs of rot—and the possible danger of its falling over—make it necessary to push it over or otherwise destroy it. At that time a new pole, similar to the old, might be commissioned, constructed, and erected; however, the passage of time since the old pole was erected can often mean that, for the new generation, the old pole is no longer considered valid. The deterioration of the pole is considered to be symbolic of the passing of time, and the patterns and carvings on the old pole no longer relevant. Perhaps this is also why any upkeep of poles is considered to be unnecessary.

The oldest totem poles are no longer in the places they were originally erected, but are instead preserved in the grounds of museums. These date as far back as 1880 and can be viewed at the Royal British Columbia Museum in Victoria, British Columbia, and also at the Museum of Anthropology in Vancouver.

1838(?)–1905

Born Mahpiya Iyapato into the Miniconjou Sioux tribe sometime between 1837 and 1839, it’s possible that Touch the Clouds was a cousin of Crazy Horse. Touch the Clouds was, according to contemporary accounts, an awe-inspiring figure to behold, standing at 6 1/2 feet tall (hence his name), lean, strong, muscular, and handsome. As well as being a great warrior with an instinct for subtle war strategy, he was a skilled and diplomatic statesman, tending to lean toward the possibility of peaceable solutions rather than battle. Touch the Clouds became leader of his particular band in 1875 after the death of his father, Lone Horn.

The Lakota had ranged the Great Plains area for generations; however, indecision about how to approach the increasing numbers of white settlers meant that the tribes were arguing among themselves, and there were several schisms. It was under these circumstances, a time of great upheaval, that Touch the Clouds grew to prominence within his particular band. Lone Horn knew how important it was that the different factions continued to communicate with one another, and Touch the Clouds inherited this skill for diplomacy. When General Custer was defeated at the Battle of Little Big Horn, Touch the Clouds and his band had been located peacefully at the Cheyenne River Agency, and, fearing that all Sioux might be blamed for what happened, Touch the Clouds strove to convince the U.S. authorities that not all Sioux were guilty. However, the Army were indeed suspicious of all Sioux, and moved to strip the tribes of their weapons and horses. Alarmed, Touch the Clouds and his men escaped from the agency, leaving everything behind them as they headed north to join other Sioux tribes.

It’s certain that Touch the Cloud’s Miniconjou men were less incendiary than the northern Sioux, and would have added an element of tactical diplomacy to the mix. Nevertheless, the amassed Sioux peoples fought in several small battles before Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse split away, leaving the Miniconjou to consider surrender; this was effected in 1877 when Touch the Clouds and his band traveled to Nebraska to surrender to General Crook.

Thereafter, the band lived in peace at the Spotted Tail Agency, and Touch the Clouds was persuaded to enlist as a scout. Crazy Horse, too, would take on this role. Both men were asked to act as scouts on a mission to fight the Nez Perce and Chief Joseph, but the mission ended in tragedy when Crazy Horse was bayoneted after escaping; Touch the Clouds was with him when he died some hours after receiving the injury.

In the fall of 1877, the Spotted Tail Agency where Touch the Clouds’ Miniconjou had been living was relocated, and Touch the Clouds and his band joined the Oglala. Many of the other Sioux bands headed north to unite with Sitting Bull, but Touch the Clouds maintained the peace among his own people and kept them at the agency. When he requested that they be transferred back to the Cheyenne River, the request was granted since the peaceable nature of Touch the Clouds, along with his great influence within his tribe, were acknowledged.

The move back to the Cheyenne River Reservation took place in early 1878; four years later most of the Miniconjou had relocated there, bringing the tribe back together for the first time in several years. Touch the Clouds felt that it was important that the Native Americans adopt the “new way,” and that they embraced schools and Christian churches. He died in 1905, in South Dakota.

The originator of this simple phrase is not known for sure, but it is believed to have been used by a Choctaw chief, Nitikechi, to describe the effects of the Indian Removal Act. The Cherokee had a similar term: “The Place Where They Cried.”

The Indian Removal Act, passed in 1830, was an innocuous name for a much harsher truth: the Native Americans of the southeastern U.S. were forced to move from their traditional homes and relocate elsewhere, to what was called “Indian Territory”—as designated by the Government. This so-called Indian Territory was made up of the eastern areas of what is now Oklahoma. Today we might call this sort of treatment “ethnic cleansing.” Members of the Chickasaw, Choctaw, Cherokee, Muskogee, and Seminole peoples were among those affected. These people not only lost the homelands where they had lived for generations, but many of them died on the way, losing their lives through a combination of starvation, exhaustion, and exposure to the elements on the long journey.

The story of the Trail of Tears is one that needs to be related in full in order to gain a complete picture of what befell the Native American people during the course of enforcing the Indian Removal Act.

The Five Civilized Tribes (Cherokee, Choctaw, Muskogee, Chickasaw, and Seminole) were living as Nations in the Deep South prior to the Act. Then, in 1831, the Choctaw were the first tribe to have the Act imposed on them. Just six years later, 46,000 Native Americans had been ejected, freeing up somewhere in the region of 25 million acres for those Americans descended from the original white European settlers.

As mentioned, the Choctaw were the first to be removed. Their journey east was planned to take place over the period between 1831 and 1833. The description of their journey is harrowing. Groups of Indians met at Vicksburg and Memphis on November 1, right at the beginning of what would be a very harsh winter. The question has to be asked whether this time of year was chosen deliberately by the U.S. Government authorities. The travelers from Memphis, trudging along with their belongings because flooding made it impossible to travel by wagons, were lashed with freezing rain, sleet, snow, and high winds. It was arranged for steamboats to take the people to any river-based destinations. The group that traveled some 60 miles up the Arkansas River found that the weather at the Arkansas Post stayed below freezing for a week, the rivers clogged with ice. There was no prospect of going anywhere; therefore the available food had to be rationed. Each person had a daily allowance of one turnip, two cups of hot water, and a little corn. But their fate was better than the Vicksburg group: their guide had no idea of the route, and lost the entire party in the swamplands of Lake Providence.

An eyewitness account from the French philosopher Alexis de Tocqueville, writing in his book, Democracy in America, gives us a glimpse of what the Choctaw people had to endure:

“ … There was an air of ruin and destruction … one couldn’t watch without feeling one’s heart wrung. The Indians were tranquil, but somber and taciturn. There was one who could speak English and of whom I asked why the Chactas were leaving their country. ‘To be free,’ he answered … We … watch the expulsion of one of the most celebrated and ancient American peoples.”

Approximately 17,000 Choctaw moved west to the designated Indian Territory, where they became the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma. Up to 6,000 of them died. Around 5,000 to 6,000 other Choctaws, renamed the Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians, stayed in Mississippi—where they suffered prejudice, harassment, and intimidation. Their dwelling places were burned, their cattle let loose, and they were beaten and tortured by the white settlers.

And the other tribes who were due to be removed from their lands?

The Creek Indians refused to move. They had signed a treaty in 1832 which opened a vast tract of their land in Alabama for the white settlers but which guaranteed that the rest of the land would remain in the ownership of the tribe, shared among the larger families. However, there was no protection from potential prospectors, who cheated the Indians out of their territories, and many Creek were rendered destitute. As a result, some Creek turned to theft, stealing both livestock and crops from the settlers. The Indians became such a “pest” that the Government ordered them to head west, and by 1836 some 15,000 Creek had disappeared from their homeland to lands west of the Mississippi River, despite their never having signed a removal treaty.

The Seminole, called to a meeting in 1832, were told that they were to move west, provided suitable land was found. The idea was to settle the Seminole on the Creek reservation in Oklahoma and amalgamate them with that tribe. This was a sore point, since the Creek regarded some of the Seminole as deserters from the Creek tribe in the first place. Not all of the Seminole had been derived from the Creek bands, but the ones who had were certain that the Creek would kill them.

In 1832, seven Seminole chiefs were sent to inspect the territory. They spent a few months there, touring around and speaking with the Creek who were already settled in the area. The chiefs signed a piece of paper to say that the land was suitable for their tribes to relocate to, but when they returned east they said that they had been forced to sign the agreement, which in any case was not legal since they did not have the jurisdiction to speak for all the people. Some of the existing Seminole, though, decided to go anyway.

However, in December 1835 another group of Seminole ambushed a U.S. Army company, killing 107 men out of 110. It was evident that the Seminole would not go to the reservation easily, and so the troops in Florida began preparing themselves for war. This became known as the Second Seminole War, which lasted for a full decade after the tribe first resisted their removal. To put the impact of this war into perspective, it’s worth bearing in mind that it cost the U.S. Government some $20,000,000, equivalent to approximately $480,000,000 today. The result was that the Seminole were forcibly ejected to the Creek lands in the West. A few others took to the Everglades, where the Government left them to their own devices.

In the meantime, there are other tribes to consider.

The Chickasaw had, unusually, actually received payment when the Government took their lands east of the Mississippi River. With this money the Chickasaw bought land from the Choctaw. The first wave of Chickasaw to remove from their territories did so in July 1837, grouping together at Memphis with all their worldly goods and chattels—including slaves—and set off across the great Mississippi River. They then followed the routes that the Choctaw and Creek had carved out before them. Once they had arrived at their designated territory, they amalgamated with the Choctaw.

Approximately 4,000 Cherokee people perished when, in 1838, they were forced to leave their homeland in the southeast after a treaty—which had never been accepted by the majority of the tribe, including their leaders—was brought into effect. This was the Treaty of New Echota, which made up part of the Indian Removal Act.

As ever, there was an undercurrent of greed surrounding the removal of the tribe. Gold had been discovered on Cherokee territory, in Georgia, just a year prior to the Removal Act. Prospectors had no qualms about trespassing on this Native American land. On top of this, in 1802 a promise had been made by President Thomas Jefferson—what happened was that the State of Georgia had been paid $1.25 million for the lands to the west (Mississippi and Alabama), in exchange for which it was promised that the land would be rid of Native Americans. Once gold was discovered, pressure was applied on the Government to keep this promise. In a legal case called, “The Cherokee Nation vs. Georgia” which took place in 1831, judges effectively ruled that the Cherokee Nation had no rights and so there was no case to be heard. A year later, however, the judges decided that only the Federal Government had jurisdiction over matters to do with the Native Americans, and that Georgia had no rights.

It was, however, not in President Jackson’s interests to protect the Cherokee nation or their lands from the Georgians. The 1830 Removal Act, in any case, gave him the ability to apply pressure on the Cherokee to sign a removal treaty and relocate elsewhere.

The next President, Martin Van Buren, allowed Alabama, Georgia, North Carolina, and Tennessee to bring together a force of 7,000 men, who rounded up nearly twice that many Cherokee and placed them in concentration camps in Tennessee before sending them off to the designated Indian Territory. It was in the camps that the Indians suffered most of their fatalities. They starved; they caught diseases; they froze to death. In the meantime, their homes were robbed, and their property and farms—where generations of Cherokee had tended, loved, and brought up their children, and buried their elders—were dispersed by means of lotteries among the white settlers.

In the winter of 1838, the remaining members of the proud Cherokee Nation were forced to walk 1,000 miles with hardly any clothing, and for the most part barefoot. Setting out from Tennessee, blankets were given to them from a hospital which had had a recent epidemic of smallpox. So as not to spread the disease, the journey was dragged out even further, as the refugees were forced to avoid settlements by means of circuitous routes.

In early December 1838 the bedraggled party arrived at the Golconda River, where they were charged $1 each—an extortionate amount at the time—to cross on the ferry. The usual charge was 12 cents. The Natives also had to wait until any other passengers had been dealt with. They huddled together wrapped in their disease-ridden blankets under a great rock called Mantle Rock. Many Cherokee died here; others were murdered by locals who then sued the Government, demanding $35 per head to bury the slaughtered Indians.

The remaining Cherokee settled in Oklahoma and, happily, recovered their strength both individually and collectively; today they are the largest Native American group in the United States.

The travail of these groups of Native Americans is marked by the Trail of Tears Historic Trail, which crosses parts of nine states and is approximately 2,100 miles long, crossing both land and water.

Natives were adept at leaving trails for each other to follow, without the signs of this being noticeable to anyone else. They were also skilled at noticing minute signs in order to track a person or an animal. Such indicators might be so tiny as a broken twig, slightly flattened grass, a stone that had been moved, or a hair. Therefore, the ability to follow such signs was a valuable skill and, for the white men, having the assistance of experienced Indian trail finders was a great asset.

Native Americans were trained early in these arts, able even as children to recognize the signs left by an enemy as well as able to cover their own potential give-away signs. Footprints—of both horse and human—could provide a great deal of information, too: whether the person was walking or running, for example, or whether he was injured. It was also possible to determine the speed of a horse by the space between its hoofprints. The marks left by different types of moccasins could even give a clue as to the identity of the wearer. Sometimes, in order to throw a tracker off the scent, Indians might walk backward for a distance; this, too, was easily discernible to the trained eye.

Other give-away signs might be a mass of pawprints of small animals as they tried to get out of the way, or a sudden flock of birds appearing in the air after they had been disturbed.

This was a piece of equipment that could be attached to either a dog or horse to enable the animal to carry things. A simple gadget, the travois consisted of two poles crossed and tied at one end which were then attached to the neck of the animal. The poles dragged behind on the ground. Loads would simply be tied to the poles or, alternatively, placed into baskets that were then tied to the poles. As well as goods, sick or injured people might be transported in this way, secured on a hide stretched across the poles.

Also known as the Sioux Treaty, this agreement was designed to make peace between the United States and a group of Native American tribes, including the Lakota (encompassing the Oglala, Miniconjou, and Brule), the Arapaho, and the Yanktonai Dakota. After a significant defeat at the hands of Red Cloud, the U.S. authorities realized that the Natives were seriously aggrieved at the encroachment of the white man upon their territory; the treaty guaranteed the Lakota their own land, which encompassed the sacred Black Hills of Dakota and tracts in Montana, Wyoming, and South Dakota. This area of land became known as the Great Sioux Reservation.

However, like others of its nature, the treaty was by no means perfect. One group who certainly suffered were the Ponca, whose territory in Nebraska was scooped up mistakenly and granted to the Lakota. Despite this having been a mistake, the Lakota forced the U.S. Government to exile the Ponca from their territory in Nebraska, which they had occupied for countless generations, and relocate to Oklahoma.

Neither was the peace long-lasting. Only 11 years after the treaty was signed, gold prospectors strayed into Lakota territory and were attacked. Despite the fact that the treaty had been violated by the prospectors, the U.S. grabbed back the Black Hills area.

The treaty, in a nutshell, paved the way for the first of the Indian reservations. It gave the Natives financial incentives to farm the land, and also stated that their children should be educated in the Christian faith. It was insisted that a team of white men should also live on the reservation to “train” the Indians; these included teachers, a carpenter, blacksmiths, a miller, a farmer, an engineer, and an agent of the U.S. Government. See also First Fort Laramie Treaty

At the heart of the Haudenosaunee, or the League of Five Nations, was a series of guiding principles collectively known as the Great Law of Peace, or Gayanashagoya. This was in turn symbolized by the Great Tree of Peace. The tree chosen to convey this concept was the eastern white pine, and the five original Nations themselves were further symbolized as five needles of the tree.

The tree was an appropriate symbol, since it was a tradition to bury weapons beneath trees to symbolize the end of a war.

?–1860

Known as a great spiritual leader and prophet, the date of Truckee’s birth is unknown but we know that he died in 1860.

An important chief of the Northern Paiute tribe, there’s an unusual incident surrounding the name of this leader, who was also known as Wuna Mucca. When in 1844 a party of Europeans encountered his tribe, Wuna Mucca rode toward them with his hands held and his robe draped in such a way that they could see that he was unarmed; he shouted across to them Tro-kee!, which means “everything is all right” in the Paiute language. However, the explorers assumed that that was his name.

Truckee’s friendly attitude can be explained in part. An ancient myth of the Paiute said that the “white brothers” would one day return. Truckee believed that all human beings were of common origin, and welcomed the white settlers, although they initially greeted him with suspicion.

Truckee’s death at Dayton, Nevada, was rumored to have been caused by the bite of a tarantula.

A particular type of reed that grows in California. Tule was used to make many different items, including baskets, matting, rafts, and the soles of sandals.

A way of carrying a heavy load by means of a piece of animal hide strapped across the forehead or chest of the bearer.

The myth of the turtle as a cosmic creature that carries the load of the world on its back exists in several societies—in India, in China and also among Native American peoples where there are several different versions of the story. For example, the creation myths of the east coast peoples, such as the Lenape and the Iroquois, tell that the Great Spirit built their ancestral lands by placing earth on the back of a colossal turtle; hence North America is sometimes given the name Turtle Island. There are many names for the turtle god: for the Hopi, he’s Kahaila; for the Abenaki, he’s Tolba; for the Mi’kmaq, he’s Mikcheech. For the Seneca, the name for the animal is ha-no-wa, to differentiate it from the mythical turtle, whose name is hah-nu-nah.

As a symbol, for Native Americans the turtle stands for healing, wisdom, and spirituality, as well as longevity, fertility, and protection. The umbilical cords of newborn female infants of the Plains peoples were shaped and stitched into the figure of a turtle and worn as a charm to ensure the baby’s well-being and security.

The turtle has also been adopted as a clan animal, or totem, by several peoples, including the Ojibwe, the Huron, the Iroquois, the Menominee, and the Lenape Delaware, already mentioned, for whom the Turtle Dance had an important part to play in certain rituals.

This is the name that several Native American tribes use to refer to the North American continent. In particular, the Haudenosaunee tribes use the term.

The reason can be found in a creation myth which is repeated in various forms by different peoples. The Sky Woman fell to earth at a time when it was completely covered by water. Animals tried to create solid land by bringing up soil from the depths of the water, but all their attempts failed until the muskrat placed the soil that he had gathered onto the back of a giant turtle; this, says the legend, became North America. In Anishnabe myth, the legend of Turtle Island is recorded on ancient birch bark scrolls.

Turtle Island as a name for North America has been revived of late, particularly by Native American activists. The name is a reminder of the myth, and of the time when Native peoples occupied the land before the coming of the Europeans.

A sixth and final tribe to join the Iroquois Confederacy (the other five tribes were the Cayuga, Iroquois, Oneida, Onondaga, and Seneca), the Tuscarora were co-opted into the Confederacy by the Oneida, becoming a part of it in 1722. By the time the European settlers arrived in America, the Tuscarora had migrated south and were living in what is now eastern North Carolina.

When first contact was made with the settlers, the Tuscarora were comprised of three tribes: the Kauwetseka (whose name meant “doubtful”), the Kautanohakau (“People of the Underwater Pine Tree”), and the Skauren (“hemp gatherers,” also known as the Tuscarora). It’s believed that the unified bands of the Tuscarora were a large tribe, of as many as 6,000 to 8,000, spread between two main groups, the Northern and Southern Tuscarora. Both suffered from the European diseases, but it was this latter group that had the most problems with settlers encroaching on their territory; tribespeople were even captured to be sold as slaves. By the early 18th century, the Southern Tuscarora saw the necessity to fight back against the white men under their leader, Chief Hancock. The Northern Tribe, under Chief Blunt, saw no reason to fight, so they remained neutral.

The first attack, in September 1711, saw hundreds of settlers slaughtered, and triggered what became known as the Tuscarora War. The next year, a large army attacked and defeated the tribe. The leader of the Northern Tribe, Blunt, was coopted into the fight by the white leader, who promised Blunt leadership over the entire Tuscarora Nation if he would help them against Hancock. Accordingly, Blunt captured Hancock, who was subsequently executed.

It was after this that a large number of Tuscarora—as many as 1,500 people—joined the Iroquois Confederacy in New York. Others found sanctuary of sorts in Virginia. A further small band of 70 or so warriors eventually settled with their families in South Carolina.

Blunt’s band in North Carolina signed a treaty in 1718 that granted the chief and his people land on the Roanoke River. Blunt was, as he’d been promised, made chief of all the Tuscarora. Any Tuscarora who did not accept his leadership, he was promised, would be considered an enemy. Indeed, there were a number of Tuscarora who did not find Blunt’s leadership to their liking, and left, many of them heading toward the New York area to join with the Iroquois.

Over 470 years since his death in 1540, the great chief, Tuskaloosa, whose name means “Black Warrior,” is still honored in the name of the city of Tuscaloosa, Alabama. It’s likely that his tribe are the ancestors of the Creek and the Choctaw.

The Spanish explorer Hernando De Soto encountered Tuskaloosa’s people when he arrived in America in the 16th century. Accounts from the time by De Soto’s party describe the chief as standing 18 inches taller than the Spaniards.

De Soto, under directions to conquer Florida, had arrived in Tampa Bay in 1539 with somewhere between 600 and 1,000 men and a couple of hundred horses. Exploring the area, the party frequently came into conflict with various tribes of Native Americans, and took to kidnapping Indians to use as slaves and translators. They also realized that taking a chief hostage would grant them safe passage across the country.

When De Soto arrived at Tuskaloosa’s village, word was sent to the chief. The settlement had been recently fortified, and featured a large mound. De Soto met Tuskaloosa on top of this mound. An account from the time describes Tuskaloosa as “a giant” and an imposing figure, seated on cushions, wearing a collar of feathers and flanked by a servant wafting a fan. Tuskaloosa did not stand when De Soto arrived.

De Soto’s men then engaged in a display of horsemanship, including a “game” with lances which they at times directed toward Tuskaloosa, who did not react. When the chief refused to hand over any of his people to act as servants for the Spanish, they instead took him hostage. The chief then offered the servants the Spaniards had demanded, but said that they would have to travel to Mabila to pick them up.

On the trip to Mabila, the Spanish noticed that the Indians were not as compliant as they would have liked. Crossing the Alabama River on rafts after the Natives denied that they had canoes, it was noticed that two of the Indian slaves were missing. Tuskaloosa was threatened with being burned at the stake unless they reappeared; the chief remained calm, and suggested that the runaways would be returned when they arrived at Mabila.

The party reached their destination in the fall of 1540. Mabila was a small settlement, with fortifications; it was obvious that these fortifications were a recent development. Another aspect that caused the Spanish to feel uneasy was the large number of young braves at Mabila. However, the Spanish were welcomed into the town with gifts and displays of dancing. Tuskaloosa expressed a desire to stay in the town rather than continue the journey with the Spaniards; when De Soto refused, Tuskaloosa went to speak with one of the elders of Mabila. De Soto sent an envoy, Juan Ortiz, to get Tuskaloosa sometime later, but Ortiz was refused entry to the house. Tuskaloosa told Ortiz that he and his party should leave peacefully or suffer the consequences.

De Soto sent men to take Tuskaloosa by force; he found that the house was full of Natives, armed to the teeth to protect their chief. De Soto demanded the porters and servants that had been promised him; when his request was refused, fighting broke out which rapidly escalated into a full-fledged battle.