Chapter 13

Checking Out Hormone Therapy and Breast Cancer

In This Chapter

Recognizing your breast-cancer risks

Recognizing your breast-cancer risks

Debating the benefits of HT and the risk of breast cancer

Debating the benefits of HT and the risk of breast cancer

Choosing an HT regimen with breast cancer in mind

Choosing an HT regimen with breast cancer in mind

Is hormone therapy (HT) risky business in terms of increasing your risk of developing breast cancer? Reports place hormones at the scene of the crime time and again, and it is clear now that long-term exposure to estrogen plus progestin therapy is strongly associated with breast cancer. Questions remain, though, about who is at greatest risk, and what guidelines exist to help you make informed decisions about hormone use. In this chapter, you can find out what researchers know for sure and what they’re still studying about HT and the risk of breast cancer.

Beginning with Breast Basics

Breast tissue and fat are the two main components of the breast. You no doubt already know about fat, so that subject needs no further explanation. But breast tissue is slightly more complex.

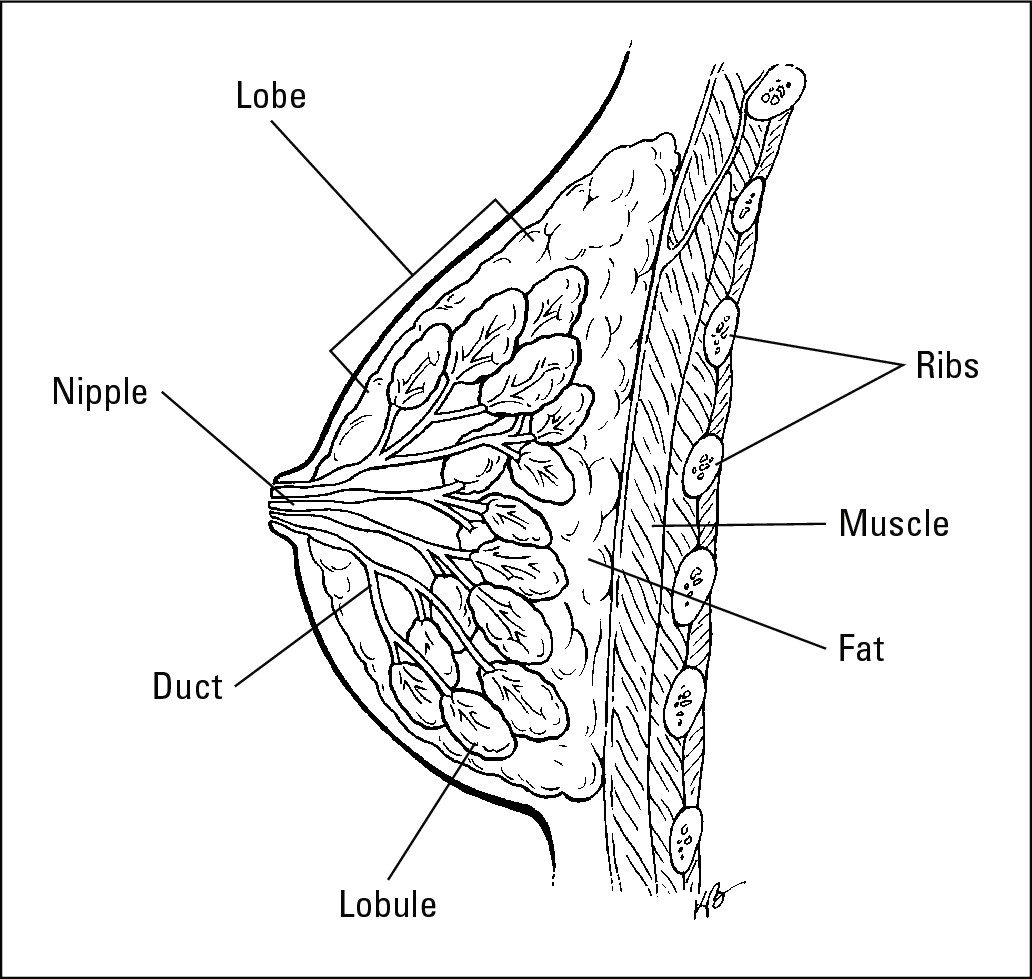

Breast tissue is composed of sections called lobes. Lobes are made up of lobules, which produce milk when you breastfeed. Ducts carry milk from the lobules to the nipple. Cancers tend to form either in the lobules or in the ducts. Figure 13-1 illustrates the parts of a breast.

|

Figure 13-1: The breast and its components. |

|

Defining Breast Cancer

Whether breast cancer forms in the lobules or the ducts, it begins when cells divide and grow at an abnormally fast rate. The cells morph into odd shapes and start clumping together to form cancerous (malignant ) tumors.

What triggers this process? Researchers know that it takes a mutation (a freak act of nature that affects the basic building blocks of cells) to get things going, but no one knows how the initial cells become mutated. Most researchers feel that a carcinogen (a cancer-causing agent) in the environment serves as the trigger. There are two main types of breast cancer and one condition that can lead to cancer:

Ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS): Technically, this is cancer, because the cells are abnormal and grow very quickly. It’s called in situ (which means in place) because the cancer cells haven’t spread beyond a very restricted area (usually a breast duct or lobule). Carcinoma in situ is sometimes called Stage 0 cancer. Although your doctor will likely recommend removing such a cancer, your treatment will probably not be as aggressive as it would for an invasive cancer.

Ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS): Technically, this is cancer, because the cells are abnormal and grow very quickly. It’s called in situ (which means in place) because the cancer cells haven’t spread beyond a very restricted area (usually a breast duct or lobule). Carcinoma in situ is sometimes called Stage 0 cancer. Although your doctor will likely recommend removing such a cancer, your treatment will probably not be as aggressive as it would for an invasive cancer.

Lobular cancer in situ (LCIS): Though contained for now in the lobules, this is not considered a true cancer. Your doctor may advise a “watch and wait” approach or a hormone treatment (more on these in the section on “Using Hormones as Therapy” later in this chapter).

Lobular cancer in situ (LCIS): Though contained for now in the lobules, this is not considered a true cancer. Your doctor may advise a “watch and wait” approach or a hormone treatment (more on these in the section on “Using Hormones as Therapy” later in this chapter).

Invasive ductile cancer: This type of cancer starts in the ducts and spreads to surrounding tissues.

Invasive ductile cancer: This type of cancer starts in the ducts and spreads to surrounding tissues.

Invasive lobular cancer: This type of cancer starts in the lobules and spreads to surrounding tissues.

Invasive lobular cancer: This type of cancer starts in the lobules and spreads to surrounding tissues.

Both invasive ductile and invasive lobular cancers can move through the breast tissue into your blood vessels, thereby gaining access to your entire body. When this happens, the cancer is said to have metastasized, or spread.

Early detection means you can treat cancer before it spreads.

Taking Care of Your Breasts

You probably already know about the importance of performing a monthly breast self-exam and getting a regular mammogram. The following sections tell you why these two simple tests are so vital to your breast health.

Examining your breasts every month

The American Cancer Society recommends that you examine your breasts for lumps and bumps every month after you reach the age of 20. And your doctor should do a breast exam as part of your yearly gynecological visit.

The American Cancer Society even offers self-exam guide cards you can hang in your shower that show you how to perform a breast exam and what you should look and feel for. Ask your gynecologist for a card, give the American Cancer Society a call (phone: 800-ACS-2345) and ask a representative to send you one, or request one at www.cancer.org .

Sometimes a lump you feel in your breast isn’t cancerous. Breast lumps can occur as the result of several breast conditions. (For more information on breast conditions, take a look at Breast Cancer for Dummies, Ronit Elk and Monica Morrow published by Wiley Publishing, Inc.)

Making time for mammograms

Have your first mammogram around age 35 so your doctor has something with which to compare future mammograms. If you’re between 40 and 49, you should have a mammogram every year or two. If you’re over 50, do it every year. At your annual checkup, make sure your medical practitioner gives you a clinical breast exam, too (essentially a more expert version of your self-exam).

Here’s a fact: The best chance of surviving breast cancer comes from early detection. Individuals who downplay the importance of annual screenings question whether mammogram screenings actually decrease the death rate. The more useful measure of the effectiveness of mammograms is whether regular mammograms increase the detection rate of new breast cancers — and they do!

If you’re a woman in your 40s, having mammograms on a regular basis can reduce your chance of dying from breast cancer by about 17 percent. For women between the ages of 50 and 69, regular mammograms can reduce deaths by about 30 percent. Early detection can reduce the numbers of women who have to undergo drawn-out and painful treatments for breast cancer. With today’s mammogram technology, healthcare providers can identify cancer at an early stage, before it invades the bloodstream and gains access to other parts of your body. Early detection allows doctors to treat breast cancer with a shorter and less invasive course of treatment.

Determining Estrogen’s Role

Although a great deal of controversy surrounds the why’s and how’s, nearly everyone agrees that estrogen plays some role in the development of breast cancer. Even the natural estrogen in your body during your reproductive years increases your risk of breast cancer because it stimulates cell reproduction in your breasts. When it comes to estrogen and menopause, here are the things most experts agree on:

Estrogen is a key promoter of breast-cancer development. So controlling estrogen levels in breast tissue should lower your risk of breast cancer.

Estrogen is a key promoter of breast-cancer development. So controlling estrogen levels in breast tissue should lower your risk of breast cancer.

The earlier you begin perimenopause and the shorter your reproductive cycle is, the lower your risk of breast cancer because these factors decrease you total lifetime exposure to high levels of estrogen.

The earlier you begin perimenopause and the shorter your reproductive cycle is, the lower your risk of breast cancer because these factors decrease you total lifetime exposure to high levels of estrogen.

Being overweight (gaining 45 pounds or more after your 18th birthday or being 20 percent over your target weight) after the onset of menopause increases estrogen levels in your body and can increase the risk of breast cancer. (Check out Chapter 18 for more information on determining your ideal weight.)

Being overweight (gaining 45 pounds or more after your 18th birthday or being 20 percent over your target weight) after the onset of menopause increases estrogen levels in your body and can increase the risk of breast cancer. (Check out Chapter 18 for more information on determining your ideal weight.)

This risk doesn’t apply to perimenopausal women who are overweight (though extra weight does put you at risk for other health problems).

Checking the Link between HT and Breast Cancer

Findings from several parts of the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) study address the relationship between hormone therapy and breast cancer. The major findings were:

Women taking estrogen plus progestin began to show an elevated incidence of breast cancer after four years of use, so much so that the treatment portion of the study was actually stopped early.

Women taking estrogen plus progestin began to show an elevated incidence of breast cancer after four years of use, so much so that the treatment portion of the study was actually stopped early.

Women taking estrogen plus progestin also tended to have larger, faster-growing tumors than did the women taking placebos in this study.

Women taking estrogen plus progestin also tended to have larger, faster-growing tumors than did the women taking placebos in this study.

Out of every 10,000 women, 38 taking estrogen plus progestin were diagnosed with breast cancer, as opposed to 30 women out of every 10,000 who were taking placebos.

Out of every 10,000 women, 38 taking estrogen plus progestin were diagnosed with breast cancer, as opposed to 30 women out of every 10,000 who were taking placebos.

Women taking estrogen alone did not have an elevated risk of breast cancer after seven years of hormone use. In fact, this therapy actually seemed to have some protective effect against breast cancer. In the group of roughly 5,000 women taking estrogen, 129 got breast cancer. In the same sized group of women taking placebos, 161 got cancer.

Women taking estrogen alone did not have an elevated risk of breast cancer after seven years of hormone use. In fact, this therapy actually seemed to have some protective effect against breast cancer. In the group of roughly 5,000 women taking estrogen, 129 got breast cancer. In the same sized group of women taking placebos, 161 got cancer.

Outcomes from other large studies of hormone use have their own findings, only some of which are consistent with what the WHI found:

In the HERS study of 2,763 women with a history of heart disease, women taking estrogen plus progestin were at increased risk for breast cancer.

In the HERS study of 2,763 women with a history of heart disease, women taking estrogen plus progestin were at increased risk for breast cancer.

In the Nurse’s Health Study (of over 120,000 participants), the duration of hormone use was significant. Breast cancer incidence was higher in women taking estrogen plus progestin (compared with those taking placebos), but only after 20 or more years of hormone use.

In the Nurse’s Health Study (of over 120,000 participants), the duration of hormone use was significant. Breast cancer incidence was higher in women taking estrogen plus progestin (compared with those taking placebos), but only after 20 or more years of hormone use.

Women in the Nurse’s study taking estrogen alone had an increased risk for breast cancer after only five years of use.

Women in the Nurse’s study taking estrogen alone had an increased risk for breast cancer after only five years of use.

All of these studies found that taking estrogen plus progestin was associated with an increase in breast cancer. In some cases, this increased risk was only apparent after a number of years of hormone use, but in the WHI study risk was apparent after only four years and increased with each additional year of hormone use.

These results of the WHI estrogen-alone study sound like good news for women who have had a hysterectomy (remember, only women without a uterus can take estrogen alone), but were somewhat surprising to researchers. Estrogen has for so long been associated with an increased risk of breast cancer, and other studies seem to support an estrogen-breast cancer link. The Nurse’s study found that women taking estrogen only had an elevated risk of breast cancer. Doctors are continuing to follow up on the women in the estrogen-only study, to find out whether lifetime risk of breast cancer is consistent with this initial WHI finding.

The risk of breast cancer for any given woman is still small, and we still don’t know what the effects of hormones on younger women will be (the WHI study also focused on the use of hormones by women between 50 and 79), so we don’t know what outcomes for younger women would be. Other studies, such as the Kronos Early Estrogen Prevention Study (KEEPS), is still (as of this writing) collecting data on the effects of hormone use in younger women and in those receiving their estrogen from a patch instead of by mouth; which may have a lowered risk of side effects. In the meantime, the WHI findings are significant and will likely help to shape the way most doctors approach recommending estrogen to their patients.

Assessing Your Risks

The two biggest risks for breast cancer are being female and being over 40. Both risks are realistically unavoidable, and they both present you with a whole bunch of positives. So who would want to avoid them?

Recognizing risks you can’t control

As frustrating as it is, some breast-cancer risk factors are out of your control. Even your own estrogen appears to heighten your breast-cancer risks (see the “Determining Estrogen’s Role” section earlier in this chapter). This section lists the risks you can’t do anything about, but you can control other factors (which we cover in the “Recognizing risks you can control” section later in this chapter):

Age: Of course it’s not fair, but the older you get, the greater your risk of breast cancer. That’s an important fact to keep in mind. When you’re younger than 40, your risk is quite low. But, after 40, your breast cancer risk increases until you’re about 80. The good news is that when you hit 80, your risk of breast cancer actually decreases a bit.

Age: Of course it’s not fair, but the older you get, the greater your risk of breast cancer. That’s an important fact to keep in mind. When you’re younger than 40, your risk is quite low. But, after 40, your breast cancer risk increases until you’re about 80. The good news is that when you hit 80, your risk of breast cancer actually decreases a bit.

Breast density: Breasts with more breast tissue than fat tissue are comparatively denser, and detecting small tumors in dense breast tissue is more difficult than detecting them in fatty tissue. At least one study has found a correlation between greater breast density and an increased risk of breast cancer.

Breast density: Breasts with more breast tissue than fat tissue are comparatively denser, and detecting small tumors in dense breast tissue is more difficult than detecting them in fatty tissue. At least one study has found a correlation between greater breast density and an increased risk of breast cancer.

Ethnicity: In North America, Caucasian women have the highest risk of breast cancer. Ashkenazi Jews are at greater risk of breast cancer than women from other cultures too (it appears that they have a higher rate of the genetic mutation known as BRCA1, which we’ll discuss momentarily). Hawaiian and African-American women have the next highest risk of breast cancer, while Latinas, Asian Americans, and Native Americans have the lowest rates of breast cancer in the United States.

Ethnicity: In North America, Caucasian women have the highest risk of breast cancer. Ashkenazi Jews are at greater risk of breast cancer than women from other cultures too (it appears that they have a higher rate of the genetic mutation known as BRCA1, which we’ll discuss momentarily). Hawaiian and African-American women have the next highest risk of breast cancer, while Latinas, Asian Americans, and Native Americans have the lowest rates of breast cancer in the United States.

Genetics: If someone in your immediate family has breast cancer, your risk of breast cancer almost doubles. If both mom and sis have breast cancer, your risk is about 21/2 times greater than the risk of a woman without breast cancer in her family.

Genetics: If someone in your immediate family has breast cancer, your risk of breast cancer almost doubles. If both mom and sis have breast cancer, your risk is about 21/2 times greater than the risk of a woman without breast cancer in her family.

If you’re worried about your family history of breast cancer, you may want to take genetic tests that look for two genetic mutations — BRCA1 and BRCA2 — that leave you more susceptible to breast cancer. However, only about 10 percent of breast cancers come from inherited genetic mutations.

The letters BRCA stand for breast cancer. BRCA1 is a genetic mutation found in people with a family history of ovarian and breast cancer. BRCA2 is a genetic mutation found in people with a family history of male and female breast cancer. Your lifetime risk of getting breast cancer if you carry one of these genetic mutations is between 50 percent and 85 percent. The presence of one of these (especially BRCA1) also increases your risk of developing ovarian cancer.

Location of fat on your body: If you wear your fat high in your body (around your midsection), your risk of breast cancer is about six times as high as that of a woman who wears her fat around her hips, thighs, and buttocks.

Location of fat on your body: If you wear your fat high in your body (around your midsection), your risk of breast cancer is about six times as high as that of a woman who wears her fat around her hips, thighs, and buttocks.

Menstrual history: The later you begin menstruating and the earlier you begin menopause, the lower your risk of breast cancer, presumably because you generate less estrogen over your lifetime.

Menstrual history: The later you begin menstruating and the earlier you begin menopause, the lower your risk of breast cancer, presumably because you generate less estrogen over your lifetime.

“Precancerous” breast tumors: Receiving a diagnosis of abnormal cell growth, carcinoma in situ, for example, increases your risk of breast cancer. (Check out the “Defining Breast Cancer” section earlier in this chapter for more on carcinoma in situ.)

“Precancerous” breast tumors: Receiving a diagnosis of abnormal cell growth, carcinoma in situ, for example, increases your risk of breast cancer. (Check out the “Defining Breast Cancer” section earlier in this chapter for more on carcinoma in situ.)

Fibrocystic condition of the breast, a condition in which you develop little lumps in your breast tissue (usually seven to ten days before your period), does not increase your risk of breast cancer.

Recognizing risks you can control

The very thought of breast cancer may make you feel panicked and helpless, but there are risk factors you can control. If a look at the list below shows that you’re already following a “breast healthy” lifestyle, give yourself a pat on the back:

Alcohol consumption: Having more than three drinks a week raises your risk of breast cancer. This fact holds true whether you’re taking hormone therapy (HT) or not, but it’s especially true if you take the conjugated equine form of estrogen. Alcohol raises the level of estrogen (the estrone type) in your body.

Alcohol consumption: Having more than three drinks a week raises your risk of breast cancer. This fact holds true whether you’re taking hormone therapy (HT) or not, but it’s especially true if you take the conjugated equine form of estrogen. Alcohol raises the level of estrogen (the estrone type) in your body.

Antioxidants: Vitamins A, C, E, beta-carotene, selenium, and glutathione are antioxidants that protect the body from premature aging and cancer (see Chapter 18 for more on antioxidants). When taken by menopausal women, these antioxidants lower the risk of breast cancer.

Antioxidants: Vitamins A, C, E, beta-carotene, selenium, and glutathione are antioxidants that protect the body from premature aging and cancer (see Chapter 18 for more on antioxidants). When taken by menopausal women, these antioxidants lower the risk of breast cancer.

Dietary fat: Dietary studies yield mixed results, but most indicate (or at least strongly suggest) that a diet high in fat, especially saturated and animal-derived fats, increases your risk. Animal fats also introduce pesticides and antibiotics into your diet.

Dietary fat: Dietary studies yield mixed results, but most indicate (or at least strongly suggest) that a diet high in fat, especially saturated and animal-derived fats, increases your risk. Animal fats also introduce pesticides and antibiotics into your diet.

Exercise: Multiple studies associate regular exercise with a lowered risk of getting an initial cancer or a recurrence.

Exercise: Multiple studies associate regular exercise with a lowered risk of getting an initial cancer or a recurrence.

Pregnancy: Women who have at least one pregnancy have a lower risk of breast cancer during their lifetime than women who have never been pregnant. But you have to read the fine print that accompanies this risk factor because you actually have a slightly higher risk of breast cancer during the ten years immediately following the birth. After ten years or so, your risk of breast cancer drops so that women with one child have a lower risk of breast cancer than women who have never borne a child. In general, the more babies you have, the lower your lifetime risk of breast cancer.

Pregnancy: Women who have at least one pregnancy have a lower risk of breast cancer during their lifetime than women who have never been pregnant. But you have to read the fine print that accompanies this risk factor because you actually have a slightly higher risk of breast cancer during the ten years immediately following the birth. After ten years or so, your risk of breast cancer drops so that women with one child have a lower risk of breast cancer than women who have never borne a child. In general, the more babies you have, the lower your lifetime risk of breast cancer.

Weight gain/obesity: Gaining more than 45 pounds at any point increases your risk of breast cancer. Breast cancer is linked to higher levels of estrogen (especially the estrone type of estrogen found in fat). (Check out Chapter 18 for additional information on weight-related issues.)

Weight gain/obesity: Gaining more than 45 pounds at any point increases your risk of breast cancer. Breast cancer is linked to higher levels of estrogen (especially the estrone type of estrogen found in fat). (Check out Chapter 18 for additional information on weight-related issues.)

Knowing for sure: Tests for breast cancer

If you find a lump in your breast, there are several ways to examine it to see if the lump is something to be concerned about. The type of test your doctor uses depends on the size of the lump and its location:

Fine needle aspiration: Right in the office, the doctor sticks a tiny needle into the lump, drains some fluid, and sends the fluid off to the lab to check for cancerous cells.

Fine needle aspiration: Right in the office, the doctor sticks a tiny needle into the lump, drains some fluid, and sends the fluid off to the lab to check for cancerous cells.

Needle core biopsy: The doctor performs this test in the hospital as an outpatient procedure, and uses a local anesthetic. The doctor sticks a needle into the suspected problem area, removes some breast tissue, and sends it to the lab to be checked.

Needle core biopsy: The doctor performs this test in the hospital as an outpatient procedure, and uses a local anesthetic. The doctor sticks a needle into the suspected problem area, removes some breast tissue, and sends it to the lab to be checked.

Open biopsy: This surgical procedure is performed in the hospital using anesthesia. The doctor makes a small incision and removes part or all of the lump, which he then sends to the lab for analysis.

Open biopsy: This surgical procedure is performed in the hospital using anesthesia. The doctor makes a small incision and removes part or all of the lump, which he then sends to the lab for analysis.

Noninvasive procedures: Non-surgical technologies such as PET scans, MRI, and ultrasounds are sometimes used for screening following an abnormal mammogram, but studies show that they miss too many cancers to be a standard replacement for biopsy.

Noninvasive procedures: Non-surgical technologies such as PET scans, MRI, and ultrasounds are sometimes used for screening following an abnormal mammogram, but studies show that they miss too many cancers to be a standard replacement for biopsy.

Using Hormones as Therapy

A special class of artificially created hormones has the potential to treat or help to prevent certain breast cancers in some women. Many cancer cells are classified as hormone receptor positive — that is, they seek out and link up with hormones that promote their growth. Estrogen or progestins connect with these cancer cells much as two puzzle pieces fit together; this linkage promotes or accelerates the cancer’s activity. Hormone therapy (sometimes called anti-estrogens or anti-progestins) work in different ways to prevent your body’s hormones from making this cancer connection.

Counting the ways

If tests reveal that your cancer is hormone receptor positive, there are basically four classes of hormone treatment that your doctor might recommend:

SERMs (selective estrogen receptor modulators). These man-made hormones work by blocking the cancer cell’s hormone receptors. It’s a little like using an outlet plug to keep your child from sticking her finger in the socket and getting hurt. Two SERMs have been prominent in the cancer news of late: Tamoxifen (designed to fight breast cancer) and Raloxifene (an osteoporosis medication that turned out to have cancer-fighting potential).The STAR study found them to be equally effective at fighting cancer, but Raloxifene has fewer side effects (see Chapter 11 for more information about SERMs).

SERMs (selective estrogen receptor modulators). These man-made hormones work by blocking the cancer cell’s hormone receptors. It’s a little like using an outlet plug to keep your child from sticking her finger in the socket and getting hurt. Two SERMs have been prominent in the cancer news of late: Tamoxifen (designed to fight breast cancer) and Raloxifene (an osteoporosis medication that turned out to have cancer-fighting potential).The STAR study found them to be equally effective at fighting cancer, but Raloxifene has fewer side effects (see Chapter 11 for more information about SERMs).

ERDs (estrogen receptor down-regulators). ERDs are a lot like SERMs, except that instead of merely blocking cancer cells’ receptors to keep them from getting a green light from hormones, they actually destroy the cancer cells’ estrogen receptors so they can’t communicate with your hormones at all.

ERDs (estrogen receptor down-regulators). ERDs are a lot like SERMs, except that instead of merely blocking cancer cells’ receptors to keep them from getting a green light from hormones, they actually destroy the cancer cells’ estrogen receptors so they can’t communicate with your hormones at all.

Aromatase inhibitors. No, these don’t have anything to do with keeping you from smelling the cookies baking. Remember that after your ovaries throw in the towel, your body’s fat cells continue to make a certain amount of estrogen that can feed growing cancers. Aromatase inhibitors keep a lid on how much estrogen your body can make after menopause.

Aromatase inhibitors. No, these don’t have anything to do with keeping you from smelling the cookies baking. Remember that after your ovaries throw in the towel, your body’s fat cells continue to make a certain amount of estrogen that can feed growing cancers. Aromatase inhibitors keep a lid on how much estrogen your body can make after menopause.

There’s one more way doctors can manipulate your hormones to help prevent cancer or the recurrence of cancer, or to try to inhibit a cancer that’s already there. Remember when we talked about how premature menopause can result from surgical removal of your ovaries, from the use of certain medications, or from exposure to radiation treatments? Doing any of these things on purpose can have the same effect: shutting down the working of your ovaries. This results in less estrogen being available to promote cancer growth. The down side, of course, is that doing these will put you into menopause.

Reviewing the risks and benefits

The benefits of using these kinds of hormone therapies are obvious. They can help to prevent an initial breast cancer in women at greatest risk, work toward preventing a recurrence in those who have had breast cancer already, help to shrink tumors before or after more traditional treatment, or augment each other, because one type of hormone therapy is sometimes prescribed when another has done the best work it can and still needs some help. Hormone therapy doesn’t typically take the place of traditional therapies such as surgery, radiation, or chemotherapy, but it can support and enhance these, or, when before them, give them a head start by shrinking the size of a tumor.

Hormone therapies of this kind, alas, are not without unpleasant side effects. You may experience hot flashes, moodiness, vaginal dryness, and weight gain. Some therapies increase your risk of uterine cancer (the breast cancer-fighting element outweighs the small less-than-one percent increase in risk, though), weaken your bones, increase the risk of blood clots, and cause upset stomach.

Choosing Your HT Regimen

If you’re a woman concerned about breast cancer (and aren’t we all?), you will find conflicting information and advice at every turn about the use of hormone therapies. When the first edition of this book was released, the type of HT believed to have the greatest correlation with breast cancer risk was estrogen-alone. New information from the WHI seems to implicate estrogen plus progestin, while the estrogen alone trial actually found a hint that estrogen use might have a small protective effect when it comes to breast cancer. Findings like these don’t make decision-making that much simpler.

Take a close look at yourself when you answer the question, “Is HT right for me?” The role of HT in breast cancer is still unanswered. Despite lots of research, all we can say is, “We don’t know.” You need to review all the available information on breast cancer and HT and then consider your own medical issues and family history.