Chapter 6

Getting a Handle on Heart Health

In This Chapter

Uncovering estrogen’s connection to cardiovascular disease

Uncovering estrogen’s connection to cardiovascular disease

Getting the goods on “good” and “bad” cholesterol

Getting the goods on “good” and “bad” cholesterol

Understanding cardiovascular diseases

Understanding cardiovascular diseases

Laying out the risk factors for cardiovascular disease

Laying out the risk factors for cardiovascular disease

Preventing cardiovascular conditions

Preventing cardiovascular conditions

Women usually don’t have heart trouble until after they reach menopause, at an average age of 51, and your risk for cardiovascular disease increases after menopause because you lose the protective benefits of estrogen. Plus, if a woman has a heart attack during mid-life, she’s more likely than a man to die from it. Why? One reason is that women have different symptoms than men. The crushing chest pains that warn men of a heart attack aren’t as common in women when they experience a heart attack.

In this chapter, we discuss heart attacks and many other types of cardiovascular disease that can affect your health during and after menopause. But you can keep your heart healthy even after menopause. And what would this chapter be if we just covered the bad news? We also discuss ways to keep your heart happy after the change — adopting a heart-healthy diet, getting a bit of exercise, and eliminating some bad habits.

Keeping Up with All Things Cardio

Okay, we’re not discussing the latest craze in cardio workouts (although Chapter 19 gives you some great ideas on fitness!); instead, in this section, we bring to light how your heart and blood vessels work so you can better understand both the role estrogen plays in your cardiovascular system as well as the connection between menopause and your cardiovascular health.

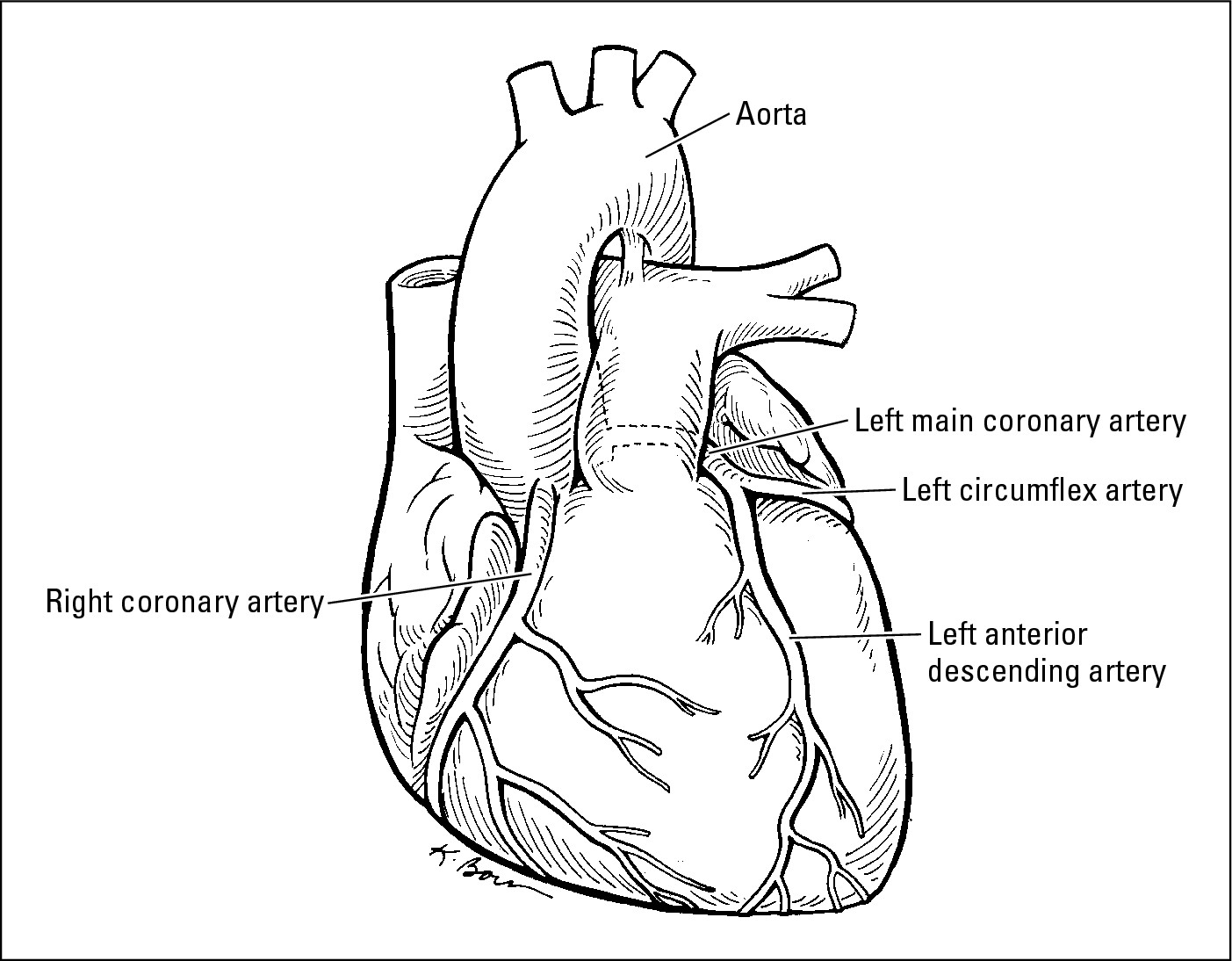

In its simplest form, your cardiovascular system consists of your blood vessels and that big pumping muscle you know as your heart. As seen in Figure 6-1, blood carries oxygen to the heart and picks up garbage on the way back.

Revealing estradiol’s role in heart health

Estrogen (in particular, the active form, estradiol) does a lot to keep your blood vessels and heart healthy and free from disease. The following list of ways estradiol protects you from getting an achy-breaky heart pulls together all the studies that have been done on estradiol and the cardiovascular system:

Estradiol lowers your blood pressure by dilating blood vessels.

Estradiol lowers your blood pressure by dilating blood vessels.

Estradiol increases the good cholesterol and lowers the bad.

Estradiol increases the good cholesterol and lowers the bad.

Estradiol keeps platelets (part of your blood) from clotting too quickly.

Estradiol keeps platelets (part of your blood) from clotting too quickly.

Estradiol acts as an antioxidant to keep fat deposits from forming on the walls of your arteries.

Estradiol acts as an antioxidant to keep fat deposits from forming on the walls of your arteries.

Estradiol facilitates the release of a chemical that relaxes blood vessels, which helps reduce vessel spasms and increase blood flow.

Estradiol facilitates the release of a chemical that relaxes blood vessels, which helps reduce vessel spasms and increase blood flow.

Linking cardiovascular disease and the menopausal woman

Estrogen, the female hormone produced in the ovaries, is good for your heart. Estradiol, the active form of estrogen, is the most beneficial form of estrogen, but (you guessed it) it’s also the type of estrogen that decreases as you become menopausal. (Chapter 2 is full of information about what your hormones do — check it out.)

Basically, estradiol is our secret weapon against all kinds of cardiovascular diseases. It’s what every man wishes he had so that he could avoid the early onset of heart problems. (See the section, “Revealing estradiol’s role in heart health,” earlier in this chapter.)

|

Figure 6-1: The healthy heart. |

|

You may have heard that before age 50, women are about half as likely as men their age to have heart disease. This statement has led many people to perceive heart disease as largely a male problem. It isn’t. Men do tend to develop heart problems about ten years earlier than women — so on average, a woman has the heart of a man ten years her junior. But just because men develop heart disease at an earlier age doesn’t mean that heart disease isn’t deadly for women. Just as many women as men die of heart disease each year.

Cardiovascular disease (disease of the heart and blood vessels) increases in women as estradiol levels decrease. After menopause, your risk of cardiovascular disease shoots way up. Between 45 and 65 years of age, men experience three times more heart attacks than women. But after age 65, watch out — women have more heart attacks than men.

We want to give you the total picture here, and unfortunately, that includes some info you may not want to hear. Of all the ways a menopausal woman can pass into the hereafter, cardiovascular disease is the most likely culprit. In fact, after menopause, you’re ten times more likely to die from cardiovascular disease than from breast cancer.

For some reason, the word hasn’t gotten out to women or their doctors. Heart disease kills more women each year than lung, breast, and colorectal cancers combined. Also, diagnoses of heart disease and heart attacks are often delayed in women because the symptoms aren’t recognized and taken seriously. See the section, “Holding off heart attacks,” later in this chapter for more information on symptoms.

Considering Cholesterol

You probably hear a lot about cholesterol — from your doctor, and from commercials for cholesterol medications. And you’re not getting forgetful when you begin to think the cholesterol goals your doctor sets for you get lower and lower. The more doctors learn about the dangers cholesterol plays in our health, the more they encourage you to avoid it.

Lowering your cholesterol isn’t the only important factor in keeping your heart healthy, but it definitely plays a strong supporting role.

At its basic level, cholesterol is fat — waxy, yellowish, oily fat. However, this fat (also known as a lipid in med speak) is critical to keeping your well-oiled body running. Your body uses cholesterol to build and repair cells and to produce hormones, such as estrogen and testosterone, vitamin D, bile (used to absorb fat), and myelin (coats the nerves). If your blood contains too much cholesterol, the cholesterol gets deposited with other crud on the inside of your blood vessels. Cholesterol travels through your bloodstream on the back of proteins, so the particles are named lipoproteins (get it? — lipid plus protein equals lipoprotein). Lipoproteins with more protein than fat are called high-density lipids (HDL), and those with more fat than protein are called low-density lipids (LDL). By the time you’re menopausal, your LDL levels have risen and often exceed those of men your age.

Breaking down the types of cholesterol

Not too long ago doctors thought that the most important cholesterol number to look at was the ratio of your total cholesterol to your HDL, or good cholesterol. Now groups such as the American Heart Association and others recommend looking instead at your individual cholesterol numbers. Lucky you, you have four of these, one for each aspect of your cholesterol:

High-density lipids (HDLs): These lipids are called the “good” cholesterol because they help prevent the buildup of plaque. Because HDLs are mostly protein with just a little bit of fat, they can carry the extra bad cholesterol back to the liver so that the body can (literally) flush it away.

High-density lipids (HDLs): These lipids are called the “good” cholesterol because they help prevent the buildup of plaque. Because HDLs are mostly protein with just a little bit of fat, they can carry the extra bad cholesterol back to the liver so that the body can (literally) flush it away.

Low-density lipids (LDLs): Also known as the “bad” cholesterol, LDLs are mostly fat and only a small amount of protein. At normal levels, they carry cholesterol from the liver to other parts of the body where it’s needed for cell repair. When LDL cholesterol is too high, it adheres to the walls of the arteries and attracts other substances. The combined glob is called plaque.

Low-density lipids (LDLs): Also known as the “bad” cholesterol, LDLs are mostly fat and only a small amount of protein. At normal levels, they carry cholesterol from the liver to other parts of the body where it’s needed for cell repair. When LDL cholesterol is too high, it adheres to the walls of the arteries and attracts other substances. The combined glob is called plaque.

Triglycerides: In addition to the fat known as cholesterol, your blood contains this other type of fat in small quantities. Triglycerides have very little protein. They’re almost pure fat, and the body uses them to store energy.

Triglycerides: In addition to the fat known as cholesterol, your blood contains this other type of fat in small quantities. Triglycerides have very little protein. They’re almost pure fat, and the body uses them to store energy.

Total cholesterol: This isn’t literally another type of cholesterol. The term refers to a measure of the total amount of cholesterol in your blood.

Total cholesterol: This isn’t literally another type of cholesterol. The term refers to a measure of the total amount of cholesterol in your blood.

You really don’t need to eat any cholesterol after the age of one because your liver produces enough cholesterol on its own. Animal products such as meat, eggs, and dairy foods are especially high in cholesterol. Even though people don’t need to eat these types of food to get enough cholesterol, most folks enjoy meat, cheese, birthday cake (which is full of butter and eggs), and other good stuff packed with cholesterol.

To find out the shape your blood is in, your doctor checks your cholesterol and triglyceride levels by taking a blood sample. The results, a cholesterol profile or a lipoprotein analysis, include your LDL, HDL, total cholesterol, and triglyceride levels. Using this information, your doctor can identify problems with your lipids and evaluate your risk of atherosclerosis.

Decoding your numbers

The more we know about cholesterol, the more complex our cholesterol reports get. Once upon a time we just got numbers that told us whether our good and bad cholesterol were good, borderline, or bad. It’s not so simple any more. Each of those four cholesterol numbers we mentioned before presents a whole range of possibilities. In the case of some of them (total cholesterol, for instance) lower is better. In others (HDL — remember, that’s your good cholesterol), a higher number is more favorable. Here’s how to decipher your report:

Total cholesterol, roughly speaking, is considered to be good if it’s under 200, bad if it’s over 240, and marginal or borderline if it’s somewhere in between. Your doctor may help you set a more specific individual goal, though, if you’re at high risk for heart disease based on weight, lifestyle, or family history. In such a case you may be advised to get far less than 100.

Total cholesterol, roughly speaking, is considered to be good if it’s under 200, bad if it’s over 240, and marginal or borderline if it’s somewhere in between. Your doctor may help you set a more specific individual goal, though, if you’re at high risk for heart disease based on weight, lifestyle, or family history. In such a case you may be advised to get far less than 100.

HDL (good cholesterol) tends to be higher in women than in men, though it often drops after menopause. Recent recommendations put good HDL ranges at 60 or more, marginal HDL between 41 and 59, and worrisome HDL levels at about 40 or below.

HDL (good cholesterol) tends to be higher in women than in men, though it often drops after menopause. Recent recommendations put good HDL ranges at 60 or more, marginal HDL between 41 and 59, and worrisome HDL levels at about 40 or below.

LDL, or bad cholesterol, has even more specific ranges. Optimal is less than 100, but anything between 100 and 129 is probably fine. Numbers between 130 and 159 are considered borderline high, 160 to 189 is high, and anything over that means you need to work with your doctor, pronto, to get your bad cholesterol down to a safer level.

LDL, or bad cholesterol, has even more specific ranges. Optimal is less than 100, but anything between 100 and 129 is probably fine. Numbers between 130 and 159 are considered borderline high, 160 to 189 is high, and anything over that means you need to work with your doctor, pronto, to get your bad cholesterol down to a safer level.

Triglycerides have their own numbers, too: less than 150 is normal; 151 to 199 is borderline; high is 200 to 499; and any triglyceride level charted at 500 or above is considered very high.

Triglycerides have their own numbers, too: less than 150 is normal; 151 to 199 is borderline; high is 200 to 499; and any triglyceride level charted at 500 or above is considered very high.

Looking at the factors

We all know that you are what you eat, but diet isn’t the only thing that controls your blood cholesterol. Exercise, insulin, obesity, and age also influence cholesterol levels.

Your genes probably have the biggest influence on your cholesterol profile. Your mother, for example, might nibble on salads, avoid desserts, and banish butter from her plate. Despite her low-fat eating habits, your mother’s cholesterol profile could actually be worse than your dad’s — even if he loves to eat cholesterol-intensive grilled cheese sandwiches and enjoys milk shakes with his grandchildren (when he’s not snacking on a cream-of-something soup). It may not seem fair, but it happens. Genes are powerful things. (Want to read more on the respective roles of genes and diets in controlling your cholesterol? Check out Controlling Cholesterol for Dummies by Carol Ann Rinzler and Martin W. Graf., M.D. [Wiley])

Regulating estrogen’s role

Estradiol (the active type of estrogen) plays a major role in the way lipids are produced, managed, broken down, and eliminated from the body. Estradiol also seems to help dilate the blood vessels and keep them from having spasms. This may be part of the reason that women are prone to cardiovascular problems after menopause.

Natural estradiol is one thing, but hormone therapy is another when it comes to protecting your cardiovascular system. Take a look at Chapter 11 for more details on this subject, but here’s the most recent word on hormones and your heart. Fair warning — it’s a little bit surprising.

First, we know that estrogen increases the level of good cholesterol (HDL) in the blood, and lowers the level of bad (LDL) cholesterol. We also know that lowering bad cholesterol and raising good cholesterol is generally associated with better heart health.

But new findings on the effects of hormone therapy on heart disease and women seem to contradict this. In fact, the study found two surprising things. First, women in the study taking estrogen and progestin were 29 percent more likely to have a heart attack, and twice as likely to have a stroke than women taking a placebo, or mock drug. Furthermore, women taking estrogen alone received no significant heart benefits from taking estrogen therapy.

The bottom line on heart health and hormones hasn’t been written yet. Women from both groups — estrogen alone and estrogen plus progestin — will continue to be followed up for a number of years. During this time, researchers will try to figure out this apparent contradiction. We’ll talk more in Chapter 11 and in Chapter 16 about how to figure out what this means for you as you make your own decisions about hormone therapy.

Connecting the dots between cholesterol and cardiovascular disease

If your artery walls are injured (as a result of smoking, cocaine-use, diabetes, or other factors), your body may react too aggressively in repairing the walls. White blood cells come to the rescue and bring cholesterol with them to patch over the damaged area. After a while, other stuff adheres to the spot and this patch becomes harder, similar to a callus. This harder stuff is called plaque. This is how bad habits or disease can lead to hardening of the arteries — what your doctor refers to as atherosclerosis.

Sometimes people have way too much LDL cholesterol and not enough HDL to carry it out of their bloodstream. When this happens, LDL cholesterol gets deposited on the artery walls and rots. (Antioxidants can prevent the rotting, which is one reason that nutritionists tell folks to get plenty of antioxidants if they want to be good to their hearts.) Other substances then collect with the rotting cholesterol to form plaque. This is how high cholesterol can lead to hardening of the arteries.

The latter process is a lot like the buildup that causes the drains in your kitchen sink to clog. Garbage goes down your sink every day, and every day, a little bit of gunk gets stuck on your pipes. Pretty soon the gunk buildup slows down the water as it moves through the pipes.

With time, calcium begins to form on the plaque, hardening the arteries. Now your arteries are narrowed and hardened, and blood has a hard time flowing to the heart. Just as the water backs up in your sink because of the clog, the blood backs up in your arteries when they become stopped up. Narrowing arteries can force your heart to pump harder to get the blood around your body. When your blood needs more pressure than normal, you have hypertension (high blood pressure).

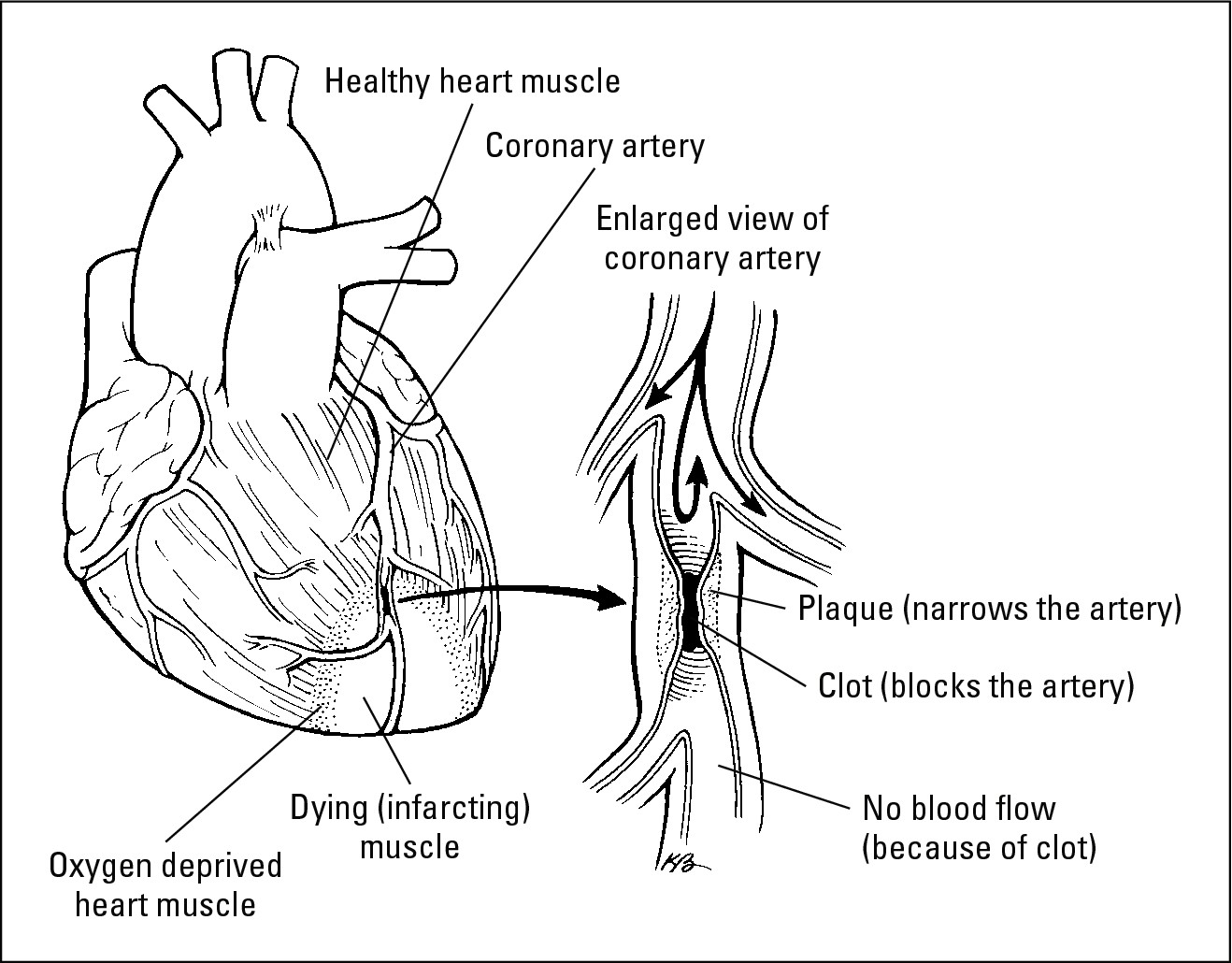

Sometimes the plaque in your artery breaks off and gets lodged in a blood vessel, as shown in Figure 6-2. Imagine pouring clog-busting chemicals down your drain; except instead of dissolving the clog, the chemicals just loosen the gunk. Then the chunk o’ gunk gets stuck in the curve of the pipe. When a piece of plaque gets stuck in a blood vessel, the area of heart muscle that gets fed by that vessel dies, and you have a heart attack.

|

Figure 6-2: The thing to look at is the clog on the right. Your heart shouldn’t look like this. |

|

Understanding Cardiovascular Diseases

A whole family of diseases affects your cardiovascular system, and a lot of inbreeding goes on in this family. For example, high cholesterol can lead to hardening of the arteries. Hardening of the arteries can lead to heart attack or stroke as well as angina. Hypertension can lead to heart attack or stroke. It goes round and round and your risk of all these conditions increases as your natural estrogen levels decline after menopause.

In this section, we introduce you to the members of the cardiovascular-disease family. Don’t worry, we talk about preventing and treating unexpected visits from these conditions, too.

Containing coronary artery disease

Coronary artery disease (CAD) affects the blood vessels (the coronary arteries ) that supply blood to your heart muscle. If these vessels are damaged, or if you have too much cholesterol in your blood, coronary arteries become narrowed or blocked by plaque as cholesterol and calcium build up inside them. This process is called hardening of the arteries, or atherosclerosis. When the heart doesn’t get enough oxygenated blood because of partially or totally blocked arteries, your heart muscle pays the price. The result is coronary heart disease. Coronary heart disease may cause angina (chest pain that we talk about in the “Avoiding angina” section later in this chapter) or a heart attack (check out the “Holding off heart attacks” section also found later in this chapter). Here’s a depressing factoid: Nearly a million women in the United States develop coronary heart disease during the course of a year.

Avoiding angina

To function properly, the heart muscle needs a constant supply of oxygen and nutrients delivered by the blood. If your veins or arteries become narrowed by fatty buildup in the artery walls (atherosclerosis), you may experience severe chest pain called angina. You feel pain because insufficient amounts of blood are getting through your veins into your heart muscle, and your heart is straining to pump enough blood to keep your body going strong.

Angina can also be caused by spasms in the blood vessels that block blood flow to the heart. Spasms can occur even if no blockages are present. Women are much more likely than men to suffer angina with no evidence of blockages.

Symptoms sometimes begin during physical activity or emotional stress. They typically last about ten minutes and go away after several minutes of rest. But many women experience chest pain while they’re resting. This is typically triggered by spasms or an arrhythmia (irregular heartbeat).

Pay attention to warning signs. As a woman, you may not feel the typical crushing, squeezing, heaviness, or burning chest pain that many men feel prior to a heart attack. Instead you may experience one or more of the following symptoms:

Back pain

Back pain

Bloating

Bloating

Chest pain while resting

Chest pain while resting

Fatigue

Fatigue

Heartburn or abdominal pain

Heartburn or abdominal pain

Jaw pain

Jaw pain

Joint pain

Joint pain

Lightheadedness/fainting

Lightheadedness/fainting

Shortness of breath

Shortness of breath

Sweating

Sweating

.jpg)

Unfortunately, a survey studying how emergency-room doctors treated patients with severe chest pain showed that men received much more aggressive and quicker treatment than women did. Also, men were twice as likely as women to be sent for coronary arteriography (a special test that looks at the coronary arteries) and bypass surgery after complaining of chest pain. If you go to the emergency room with chest pain or anything else that could be symptoms of a heart attack, insist — or make sure whoever accompanies you insists — that a heart attack be taken into serious consideration as a possible cause.

Holding off heart attacks

Menopausal and postmenopausal women are at an increased risk of heart attack (myocardial infarction in medicalese). Most women experience heart attacks after age 60, but heart disease may begin as early as the preteen years. Cholesterol accumulations have been found in girls as young as ten years old. These accumulations in young children, called fatty streaks, sometimes turn into more significant buildup later in life.

Blocked arteries often cause heart attacks. Either plaque breaks loose or a blood clot (a mass of solidified blood) blocks an artery cutting off blood supply to the heart. If the blockage remains in place for 5 to 10 minutes or more, the piece of the heart muscle fed by that artery begins to die.

Vessel spasms and arrhythmia are two additional causes of heart attacks, and evidence suggests that they’re more common triggers of heart attack in women than in men. Spasms constrict your coronary arteries so blood can’t get to the heart. Spasms can also cause plaque to break away from the vessel and get lodged in an artery, cutting off blood supply that way. Arrhythmia, or an irregular heartbeat, can mess up the pumping action of the heart and cut off blood supply as well.

Women often have different symptoms before a heart attack than men do. The symptoms are easy to overlook because they’re often subtle and typical of many other, less serious problems. Often, women look back and say, “Oh yeah, now that you mention it, I felt that way yesterday,” after the heart attack has already occurred.

An unfortunate byproduct of a heart attack is a condition called ventricular fibrillation. Ventricular fibrillation refers to an irregular heartbeat that happens when the main pumping chambers of the heart, the ventricles, can’t get coordinated; therefore, the blood can’t get to the far reaches of the body.

.jpg)

Fending off hypertension

High blood pressure is another one of those health issues that’s more likely to pop up as you get older. Until age 55, women usually have lower blood pressure than men. Between 55 and 65 years of age, women and men are about equal in the incidence of high blood pressure. After 65, more women than men have high blood pressure. So, just when you’re dealing with all the symptoms connected with menopause, you may develop high blood pressure (your doctor may call it hypertension ).

About half of all Caucasian women and three-quarters of African-American women over 50 have hypertension. For some reason, African-American women are more prone to hypertension than Caucasian women. Mexican-American women have about as high a chance of having hypertension as Caucasians, but Cuban-American and Puerto Rican women have lower incidence of hypertension.

No one knows why people develop high blood pressure. About 5 percent of the time, high blood pressure is caused by a condition such as diabetes or pregnancy, and it often goes away with treatment or resolution of the precipitating condition.

To visualize high blood pressure, think of blowing up a balloon. As you hold the balloon opening to your mouth and blow, the air in your mouth is under a great deal of pressure because you’re trying to pass it through the small opening in the balloon. Now, think of your heart as your cheeks and your arteries as the balloon opening — the smaller the balloon opening, the more pressure in your cheeks as you try to blow. So, if your blood vessels get smaller due to cholesterol buildup, or whatever, your heart has to pump harder to pass the blood through these narrower openings. The result: Your blood pressure rises.

High blood pressure can lead to heart attack, kidney damage, bleeding in the retina behind your eyes, and stroke. For these reasons, having your blood pressure checked routinely after you reach 40 (or at any age) is critical.

Many women develop high blood pressure because of obesity. Fortunately, these women often can reduce their blood pressure dramatically by switching to a heart-healthy diet (see Chapter 18) and losing weight.

If you’re not overweight, you may need to try some other types of intervention. Some women are able to regulate their blood pressure by reducing anxiety through meditation or other relaxation techniques. If these techniques don’t work, medication may be the answer to getting your blood pressure under control. You may have to work with your doctor to find just the right type of drug and dosage. One drug may work for others but not for you. And, for some reason, drugs used to control blood pressure are more effective in men than women.

Staving off stroke

A stroke can occur for one of two reasons: either a blood clot blocks the flow of blood to your brain or a blood vessel in your brain ruptures. In either case, oxygen-rich blood can’t get to the brain to nourish it. The problems a stroke causes depend on the location and severity of the stroke, but speech problems, physical weakness, paralysis, and permanent brain damage are all possible stroke complications. Many stroke victims go through rehabilitation programs that restore full or partial function to the affected areas of the body.

Here are the symptoms associated with strokes:

Difficulty talking or understanding speech

Difficulty talking or understanding speech

Dizziness

Dizziness

Loss of vision, particularly in just one eye

Loss of vision, particularly in just one eye

Unexplained numbness or weakness in the face, an arm, a leg, or one side of your body

Unexplained numbness or weakness in the face, an arm, a leg, or one side of your body

A transient ischemic attack (TIA) is like a mini-stroke. During a TIA, blood flow to the brain is interrupted (usually by a blood clot). The symptoms of a TIA usually last only 10 to 20 minutes and end when blood flow returns to normal. At worst, the symptoms of a TIA last 24 hours; symptoms of a stroke can last a lifetime. Pay attention to TIAs because they can be early warning signs of an impending stroke. Half the people who have a TIA suffer a stroke within a year.

.jpg)

Checking Out Your Risk Factors for Cardiovascular Disease

Many of the risk factors for complications related to cardiovascular disease are more risky for women (particularly menopausal women) than men, but many are risk factors for both men and women — even men and women who seem to be in good health:

Alcohol: Women don’t produce as much of a specific enzyme used to break down alcohol (alcohol dehydrogenase) as men do. So women tend to feel the buzz from alcohol earlier than men, and alcohol stays in their systems longer. Three or four drinks a day will cause a noticeable rise in blood pressure. (We outline the dangers of high blood pressure in the earlier “Fending off hypertension” section.) In large doses, alcohol acts as a poison and kills heart tissue.

Alcohol: Women don’t produce as much of a specific enzyme used to break down alcohol (alcohol dehydrogenase) as men do. So women tend to feel the buzz from alcohol earlier than men, and alcohol stays in their systems longer. Three or four drinks a day will cause a noticeable rise in blood pressure. (We outline the dangers of high blood pressure in the earlier “Fending off hypertension” section.) In large doses, alcohol acts as a poison and kills heart tissue.

Cholesterol: Low HDL levels and a high LDL-to-HDL ratio increase a woman’s risk for cardiovascular disease. After menopause, most women’s HDL levels drop a little bit. A bigger change takes place in your LDL level. As women age, LDL levels keep rising — especially between the ages of 40 and 60. So your HDL and LDL levels and your LDL-to-HDL ratio are usually worse as you age.

Cholesterol: Low HDL levels and a high LDL-to-HDL ratio increase a woman’s risk for cardiovascular disease. After menopause, most women’s HDL levels drop a little bit. A bigger change takes place in your LDL level. As women age, LDL levels keep rising — especially between the ages of 40 and 60. So your HDL and LDL levels and your LDL-to-HDL ratio are usually worse as you age.

Cocaine use: Cocaine and its relative — crack — are seriously dangerous drugs. Cocaine, whether snorted, smoked, or injected, can cause serious damage to women’s arteries and heart. Cocaine and crack use can cause spasms in the coronary arteries, restrict oxygen flow to the heart, and cause arrhythmia. If a woman has a previous coronary-related condition such as a mitral valve prolapse (heart murmur), cocaine can cause sudden death.

Cocaine use: Cocaine and its relative — crack — are seriously dangerous drugs. Cocaine, whether snorted, smoked, or injected, can cause serious damage to women’s arteries and heart. Cocaine and crack use can cause spasms in the coronary arteries, restrict oxygen flow to the heart, and cause arrhythmia. If a woman has a previous coronary-related condition such as a mitral valve prolapse (heart murmur), cocaine can cause sudden death.

Diabetes: High blood pressure, excessive weight, and inactivity can lead to adult-onset diabetes in women. Although adult-onset diabetes isn’t real common, it’s very serious for menopausal women. Diabetes can cause a host of other problems, one of which is an increased risk of heart disease. Here’s the scoop on women, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease:

Diabetes: High blood pressure, excessive weight, and inactivity can lead to adult-onset diabetes in women. Although adult-onset diabetes isn’t real common, it’s very serious for menopausal women. Diabetes can cause a host of other problems, one of which is an increased risk of heart disease. Here’s the scoop on women, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease:

• Women over 45 (menopausal women) are twice as likely as men their age to develop diabetes.

• Women with diabetes are more than five times as likely to have some type of coronary “event” (we’re not talking about a gala here; we’re talking about a heart attack, angina, and so on) than women without diabetes.

• Women with diabetes are four times more likely to die of a heart attack. In fact, 80 percent of all people who suffer from diabetes die of heart attacks

Fortunately, adult onset diabetes can often be prevented or controlled through weight loss, exercise, and a healthy diet.

Excessive weight: If you weigh 20 percent or more than your target weight, you’re overweight. (Chapter 18 has a chart you can use to determine where you are in relation to your target weight.) For example, if your target weight (how much people your height and build should weigh) is 125, you’re overweight if you weigh 150 pounds or more. Excessive weight increases your risk of high blood pressure, heart disease, stroke, and even diabetes. Because excessive weight leads to many diseases and complications, it only makes sense that losing the excessive weight can lower your risk for many diseases and complications. Excessive weight is a huge and growing problem (no pun intended) — more than one-third of all Caucasian women and half of all African-American women in the United States are overweight.

Excessive weight: If you weigh 20 percent or more than your target weight, you’re overweight. (Chapter 18 has a chart you can use to determine where you are in relation to your target weight.) For example, if your target weight (how much people your height and build should weigh) is 125, you’re overweight if you weigh 150 pounds or more. Excessive weight increases your risk of high blood pressure, heart disease, stroke, and even diabetes. Because excessive weight leads to many diseases and complications, it only makes sense that losing the excessive weight can lower your risk for many diseases and complications. Excessive weight is a huge and growing problem (no pun intended) — more than one-third of all Caucasian women and half of all African-American women in the United States are overweight.

High blood pressure: High blood pressure can lead to heart attacks and stroke because it stresses out the blood vessels. Stress on your blood vessels can constrict the arteries and cause plaque to separate from the vessel wall and clog your arteries.

High blood pressure: High blood pressure can lead to heart attacks and stroke because it stresses out the blood vessels. Stress on your blood vessels can constrict the arteries and cause plaque to separate from the vessel wall and clog your arteries.

Inactivity: For women, inactivity is the most common risk factor for cardiovascular disease. Most women never had the time or chance to incorporate a “workout” into their busy schedules. Chauffeuring children and performing household chores, intermingled with a 40- to 50-hour workweek, often leaves women with no time or desire to take a walk or regularly attend an exercise class. Husbands and children (aren’t they precious?) may question how you can waste an hour on an activity that doesn’t directly benefit them or the household. Well, the fact is that you must make the time (just as your husband or kids do) for physical activity. Physical activity is not a waste of time — it lowers a woman’s risk of heart problems by a whopping 50 percent. And keep in mind that half of all women die of cardiovascular disease. Take a look at Chapter 19 for some ideas on increasing your activity level.

Personality: Many people believe that too much stress results in high blood pressure and heart attacks. Whether you’re talking monkeys or people, the research indicates that it’s a control thing, not a just a stress thing. Women (and monkeys) who feel in control of their lives are much less likely to have heart disease. Cholesterol profiles are also much better for women who feel in control of their jobs, lives, or homes. When you feel out of control, you’re more likely to feel cynical or hostile, or you may feel sorry for yourself. Researchers have also linked these personality traits to a higher incidence of heart disease.

Personality: Many people believe that too much stress results in high blood pressure and heart attacks. Whether you’re talking monkeys or people, the research indicates that it’s a control thing, not a just a stress thing. Women (and monkeys) who feel in control of their lives are much less likely to have heart disease. Cholesterol profiles are also much better for women who feel in control of their jobs, lives, or homes. When you feel out of control, you’re more likely to feel cynical or hostile, or you may feel sorry for yourself. Researchers have also linked these personality traits to a higher incidence of heart disease.

Smoking: Cigarette smoking triples your risk of heart attack and angina. Even women who smoke fewer than five cigarettes a day double their risk of heart disease. When you inhale smoke, your heart beats faster, your blood vessels constrict, and your circulation slows down. The nicotine in cigarettes promotes blood clots (which can lodge in your arteries to cause heart attacks or stroke). Smokers also have a greater risk of high blood pressure and emphysema.

Smoking: Cigarette smoking triples your risk of heart attack and angina. Even women who smoke fewer than five cigarettes a day double their risk of heart disease. When you inhale smoke, your heart beats faster, your blood vessels constrict, and your circulation slows down. The nicotine in cigarettes promotes blood clots (which can lodge in your arteries to cause heart attacks or stroke). Smokers also have a greater risk of high blood pressure and emphysema.

Being Smart about Your Heart

Eating a healthy diet, watching your weight, exercising routinely, avoiding unhealthy habits, and getting annual medical examinations are the best ways to prevent cardiovascular problems.

Weighing an ounce of prevention

Keeping your blood clean and lean really helps prevent hardening of the arteries, which is the source of many serious problems. Controlling your cholesterol boils down to eliminating unhealthy habits (smoking, drinking too much alcohol, using recreational drugs, and so on), sticking to a healthy diet (check out Chapter 18), and exercising five days a week for a half-hour (turn to Chapter 19).

If you’re not able to control your cholesterol through lifestyle changes, you and your doctor can consider alternatives. A variety of medications are available today that can lower your cholesterol.

But many people develop hypertension even though their cholesterol levels are terrific. Doctors always seem to check your blood pressure as soon as you step in the door. So keep those doctor appointments and, if your blood pressure is high, seek help. Your doctor will work with you to find the right medication for you, but you’re the one who has to take it every day if it’s going to work.

Routine checkups (that means at least once a year) with your internist and gynecologist should prevent cardiovascular problems from sneaking up on you.

Treating what ails you

If you maintain regular appointments and seek help when you feel any weird happenings in your heart (such as palpitations or pain), you should be pretty safe. Of course, you have to follow the advice given to you by professionals when problems are detected. If you have high blood pressure, you need to take your medication. Even though you usually have no symptoms with hypertension, not taking your medication can cause trouble — same goes for cholesterol. Many people have no symptoms when their cholesterol is high, but if they go untreated, faulty cholesterol levels can cause a world of problems.

Today, a variety of medications are available to treat these conditions. Sometimes you and your doctor will have to experiment a bit to find out which medicines work for you, but the effort is worth it because the reward is a prolonged life.