KATARZYNA KWAPISZ WILLIAMS

In looking at their history and identity the Poles show a clear tendency to highlight sufferings as the key to the nation’s philosophy of history. For more than three centuries suffering has been a constant historical determinant of Poland and the price paid for patriotism. Suffering can mean defeat; it can be regarded as proof of the absence or impotence of God. Polish spirituality, however, puts suffering in a different perspective. Suffering is seen as a sign of chosenness and the specific mission of Poles. The notion of chosenness is historically rooted. It explains all events in the light of the role and position of the Polish nation in God’s plans.

Chrostowski, ‘The Suffering, Chosenness and Mission of the Polish Nation’

The image of Poland’s ‘chosenness’ and messianic role has been recycled and reused by Poles in different historical contexts over the centuries to alleviate the pain of defeat they have suffered at various hands. The belief that Poles as a nation are exceptional in comparison to other nations was adopted from the messianic doctrine popular in Europe as early as the sixteenth century, further developed as a response to the long and unsuccessful struggle for independence, especially during the partition of Poland (1772–1918), and recycled in the coming years of occupation (Chrostowski).1 Polish Romantics, writing in the aftermath of the failure of the 1830 Uprising against Russia, most effectively evoked the image of Poland as ‘a Christ of Nations.’ There have been many examples of literary works created since the Romantic period in which the motif of an uprising, struggle for independence, and the idea of suffering and heroism of the Polish nation is prominently exhibited.2 This collective, national martyrology continued during the Second World War, enforcing the self-image of Poles as simultaneously betrayed victims and heroes. The failure of the last national uprising before the end – at least for most nations – of the Second World War, plus the following years under the Soviet rule, enforced the position of the myth of heroic struggle for freedom in Polish culture. Finally, in post-Soviet Poland, the growing number of museums and monuments – an imperative of living memory – changed, as Małgorzata Sugiera claims, from a ‘necessary and slow process of mourning into automatic and institutionally encouraged duty of remembering’ (14).3

Stories of the 1944 Warsaw Uprising, one of the most tragic and least known episodes of the Second World War, are told in numerous ways and contexts. Since 2006, to commemorate the anniversary of the Uprising, the Warsaw Uprising Museum has organized annual performances that celebrate the memory of war and retell the events of 1944 in, as they claim, ‘a modern way.’ According to the Museum’s official sources, its objective is to ‘universalise the experiences of war, occupation and the Uprising itself through classical literature,’ and to question the way that the Warsaw Uprising is usually presented and understood in Poland, that is, ‘either as a tiresome Polish martyrdom, or as an experience sanctifying Poland … [more] than any other nation’ (‘Odczytać Powstanie’). Although the Museum’s efforts, closely aligned with the conservative political party Prawo i Sprawiedliwość (Law and Justice), imply institutionalisation of national memory and continuation of national mythology, the productions organized and sponsored by the Museum function in a rather unexpected way: by questioning what Sugiera has called the ‘privileged ways of representing the past’ (14). Moreover, young directors with unconventional approaches to art and history have used diversified forms of expression that attract young audiences.4

The audience that gathered in the Warsaw Uprising Museum on 1 August 2008 to watch Paweł Passini’s stage play Hamlet’44 was encouraged by the production to reflect on the heroism of fighting and dying for one’s country, to consider death, its purpose and meaning, but also to think about Polish war history in universal terms, as existential experiences of freedom and fear known from philosophy and world literature (‘Odczytać Powstanie’). Most probably Passini’s audience anticipated, maybe even desired, the repetition of certain motifs used in ‘modern Shakespeare’ productions. Yet, they were perhaps surprised to hear the famous ‘To be or not to be’ soliloquy recited by a group of young actors portraying insurgents who fall dead on the gravel under the fire of a Nazi squad, get up immediately, and then fall again. And get up and fall again. And get up and fall again. Reused and reclaimed in numerous cultural, social, and political circumstances, Shakespeare proved that the best way to understand his texts is by appropriating them to the local context. There may also be no better way to comprehend the terrifying events of war than by exposure, repetition, recycling.

15.1 Maciej Wyczański (Hamlet) and Łukasz Lewandowski (Horatio) in Hamlet’44, directed by Paweł Passini, Museum of the Warsaw Uprising, 2008. Photograph by Julia Sielicka-Jastrzębska, reproduced courtesy of the Museum of the Warsaw Uprising, Warsaw.

The Warsaw Uprising (1 August to 3 October 1944) was organized as a part of ‘Operation Tempest’ by the Polish resistance movement – the Home Army (Armia Krajowa) – in the hope that, with Allied air-drops of supplies (weapons and food) and the military support of the advancing Red Army, Warsaw could be liberated from Nazi occupation and that the authorities of what became known as the ‘Polish Underground State’ could seize power in Poland before the Soviets did so.5 However, the expected support did not arrive and, after sixty-three days of struggle, the Polish forces surrendered. During the Uprising the city of Warsaw was razed; between 130,000 and 180,000 civilians died,6 and 16,000 Home Army soldiers were killed or reported missing.

The Uprising has always been a controversial and sensitive issue. After 1945, once the Communists seized power in Poland, reference to the Uprising became unpopular because it cast the Communists in a bad light, drawing attention to their failure to lend assistance to the Poles during the fighting. The legend of the Uprising remained; it lived underground and provided an arena for a struggle against Communism. Following the fall of the USSR in 1989, Polish history, which had been so often an uncomfortable topic, began to be reinvestigated and retold. Yet, the Uprising became a difficult ‘myth’ to cultivate. The young and the intellectuals died, as some say, ‘without weapons and without reason,’ but – as it is officially proclaimed – having achieved ‘moral victory’ (Sidorowicz 47).

For today’s culture of sorting and separating, reusing and recycling, refashioning myths, the process of retelling stories and revaluating history does not seem problematic. In 2008, on the occasion of the sixty-fourth anniversary of the Warsaw Uprising and as part of the project ‘Reading the Uprising – Theatre/Museum,’ Paweł Passini directed Hamlet’44. Through Shakespeare, Passini presented a contemporary interpretation of the Second World War’s tragic events and the struggle of young insurgents during the Uprising.7

One of the most violent periods in human history became a perfect age for Shakespeare to comment on. After all, Shakespeare was familiar with wars: ‘warfare is everywhere in Shakespeare,’ as Charles Edelman observed; his history plays are all about battles and even in ‘the most non-military comedies … there is a great deal of military imagery’ (1–2). In addition, his works have always functioned as reusable goods.8 During the war Shakespeare was ‘repossessed’ by secret and military theatres, by theatres in exile, salvaged in prisoner of war camps and concentration camps, recovered by those who witnessed the evil of war, as some of the essays in this volume reveal. It is no surprise, then, that after the war he also became a part of the postmodern discourse of recycling the past, its values, and myths – a discourse that promotes ‘a narrative of cultural production and progress that negates the idea of significant loss’ (Kendall and Koster). He became a part of the process of modern cultural production that is often defined by such notions as ‘bricolage,’ ‘différance,’ ‘simulacrum,’ and, most frequently as ‘appropriation’ and ‘recycling.’ Shakespeare is ‘already disseminated, scattered, appropriated, part of the cultural language, high and low’ (Garber 7). As Garber claims, ‘the word “Shakespearean” today has taken on its own set of connotations,’ while modern Shakespeare ‘often becomes a standardized plot, a stereotypical character, and, especially, a moral or ethical choice – not to mention the ubiquitous favorite, “a voice of authority.”’ He appears in journalistic jargon, is often sampled ‘in forms from advertising to cartoon captions,’ and his plays are now being used, ‘regularly and with success, to teach corporate executives lessons about business’ (4–7). Shakespeare also proved that recycling, after all, ‘can make you feel good’ (Hawkins 95).

15.2 Tomasz Dedek (Claudius), Paweł Pabisiak (Guildenstern), and Michał Czachor (Rosencrantz) in Hamlet’44, directed by Paweł Passini, Museum of the Warsaw Uprising, 2008. Photograph by Julia Sielicka-Jastrzębska, reproduced courtesy of the Museum of the Warsaw Uprising, Warsaw.

Shakespeare’s works have always functioned as re-usable goods, even for the playwright himself.9 He was already ‘recycled’ in the Restoration period and then, for centuries, his texts were modified to please the tastes of the reading public and critics. The eighteenth century taste for adaptation, for cuts and additions, modernization of language, simplification of plot, changing characters and scenes, for interludes, afterpieces and divertissements, evinces extravagant if not violent ways of materializing Shakespeare both on stage and page.10 Though adaptations were traditionally criticised as ‘a symptom of a diseased popular taste’ (Marsden 7) or as a ‘deterioration and degradation of Shakespeare’s art’ (Bristol 65), they have been often preferred over the original text, because they were informed by contemporary life.

Modern adaptations obviously assume various degrees of distance from the original, but they all attempt to reclaim Shakespeare for the present. We have finally accepted the fact that literary works, canonical works especially, in spite of all their universality and timelessness, are like other products of modern culture – they are products with a limited useful life: each culture and generation must recover them for further use of their own. Especially after Jan Kott’s Shakespeare, Our Contemporary (1965), many theatre directors were inspired to recycle Shakespeare and relate him to present audiences. One of them, Charles Marowitz, who authored very bold recensions of Shakespeare’s works (see his The Marowitz Shakespeare), believes that ‘recycling’ enables the contemporizing of Shakespeare, but it also allows one to produce true art, keep theatre alive, and challenge ‘the assumptions of the past’ (‘Improving’).11

Hamlet’44 was one such attempt to challenge the ‘assumption of the past,’ to recycle the old play, together with Poland’s history and memory. The war does not appear in allusions only; the performance was all about war and war drama; some scenes even confront the audience with projected images from the actual war. The play was staged outdoors, in the park surrounding the Warsaw Uprising Museum, located in the city district (Wola) where the fighting had been particularly fierce and where mass executions once took place. Some elements of the performance were projected on the Memorial Wall on which the names of thousands of insurgents who died during the Uprising are engraved. Thus the stage became a space marked with a very special meaning: it was the place of a real battlefield and a war grave.

As with other nations, in Poland Hamlet was often a vehicle for social and political commentary. During the long struggle for independence under various occupants, debates about freedom raged, and Hamlet was used and regarded as representative of the Polish nation, an ‘intellectual, prisoner, and fighter’ (Sułkowski 171): ‘the Polish Prince.’ With the end of Communism in Eastern Europe in 1989 and the end of ‘the struggle for the national cause,’ the play became less attractive and less useful, giving way to Macbeth, which brought a different vision of war – not a national heroic struggle, but a global conflict and a universal culture of war. Now, in 2008, Hamlet returned but served a different function. The play was recycled to comment on sensitive matters of the past, of political and ideological implications, to help find new myths in a different, new Europe. It was recycled to refresh our memory, free it from banalities and simplifications. It was staged to encourage contemplation of the fact that reality is never black or white.

Since the Uprising became a legend in Poland and ‘the myth of the heroic dash of [the citizens of] the Capital’ to liberate Warsaw from Nazi German occupation is still alive in Polish society (Sidorowicz 46), Hamlet’44 seemed to make an attempt to measure its strength against the official interpretation of the Uprising: that it was necessary, unavoidable, heroic, and in some respect, even successful.12 In the 1990s, Bogusław Sułkowski conducted sociological research on the Polish reinterpretation of Hamlet on an audience who ‘has not personally experienced the totality of war … the first generation whose physical existence has not been endangered.’ He concluded that modern artists and audiences must revaluate history and develop new tools for interpreting reality; in doing so they are to be inspired by Shakespeare, and ‘they, in turn, inspire Shakespeare’ (222) – that is, they appropriate his texts for their individual use. However, since Shakespeare’s text in Hamlet’44 has been significantly rewritten and extended with many additional lines and plot elements, some reviewers wondered why Shakespeare was used here at all. They considered whether the only reason for this production was the fact that the director found a soldier with the pseudonym ‘Hamlet’ on the list of dead insurgents (Drewniak). Some insisted that introducing the themes of war into the play was rather artificial and unjustified, as well as an abuse of Shakespeare’s genius (Bończa-Szabłowski). Other reviewers believed that inserting Hamlet into the heroic history of the Warsaw Uprising seemed quite natural, since that was the time when Poles faced Hamlet’s dilemma: deciding whether ‘to be or not to be’ symbolically, as a nation, or, literally, as individuals. For the director of the performance and the organizers of the ‘Reading the Uprising – Theatre/Museum’ project, Shakespeare was to help to tell the war story, narrate the Uprising ‘without [mental] complexes, or even with some vigour and spirit’ (‘Powstańcy u Szekspira’). Recycling Hamlet, as the director clarified, was to help to extract the tragic dimension of the Uprising (Kopciński 19) to the utmost, to present its appalling and grievous facts, but also to reflect its complex nature, which still offers no simple interpretation. Adam Zamoyski explained that, for Poles, the Warsaw Uprising is

the subject of a never-ending conundrum – was the rising an act of heroic if doomed self-defence, a historical imperative, or was launching it an act of criminal recklessness, resulting in the death of hundreds of thousands and the destruction of the capital? … The issue will not go away because it has affected and continues to affect life in Poland … Despite the meticulous reconstructions, one cannot walk around Warsaw today without being aware that one is walking over a battlefield.

Undoubtedly, recycling old images and stories and looking at complex events and situations through familiar lenses helps to understand the past that lives only in these stories. Shakespeare is constantly refashioned and recycled ‘for the same reasons that we are constantly reinterpreting history, re-evaluating the lives of its leading figures, and revising the significance of its most seminal events; trying always to dig deeper and learn more than the generations before us’ (Marowitz, ‘Improving’). The play, and Hamlet’s dilemma in particular, inspired interpretations that, in the Polish context, have become vital comments on war and its dimensions.13 On the one hand, Hamlet’s dilemma became a metaphor of a moral dilemma: ‘to fight or not to fight,’ raising the question of moral paralysis, the inability to act. On the other hand, it expressed the extremities of the situation, a unanimous war cry, without restraint, without doubts, and was not posed as a question. Though the theme of hesitation and inability to act has usually been present in Polish appropriations of the play, the phrase ‘To be or not to be’ became a symbol of a moral duty: to fight for the country’s independence or die as a nation. Jacek Trznadel observes that ‘[t]he myth of Polish Hamlet testifies to … the vitality of a certain idea and the ethos of a hero who wants to act, even in the most difficult conditions, in the name of truth and justice’ (310). This hero ‘who wants to act’ remained the strongest Shakespearean image associated with Poland’s struggle for independence.

Polish Hamlet has never faced a real interpretive alternative; ‘To be’ usually meant the struggle of the repressed Polish nation for freedom – for survival – while ‘not to be’ meant not fighting, as Kott claimed in his influential text ‘Hamlet po XX zjeździe’ [Hamlet after the Twentieth Congress] (1956: 3).14 It may at first appear that the production of Hamlet’44 continued this rhetoric of fighting for a national cause as the main dilemma of the Prince and one also shared by other characters. In such a view, the question is seemingly simple: whether or not to take part in the national struggle, to fight or not to fight. However, in the context of the Uprising, which, as many commentators and survivors believe,15 was bound to fail from the beginning, the question ‘To be or not to be’ becomes quite complex: does ‘to be’ mean ‘to fight and die achieving moral victory’ or rather ‘not to fight and survive.’ Passini explained that ‘in our performance “to be” means, for them [the insurgents], “to go”’ (qtd in Kopciński 19), to fight and sacrifice one’s life. The performance, however, showed that it is difficult, if not impossible, to provide the right answer to the question.

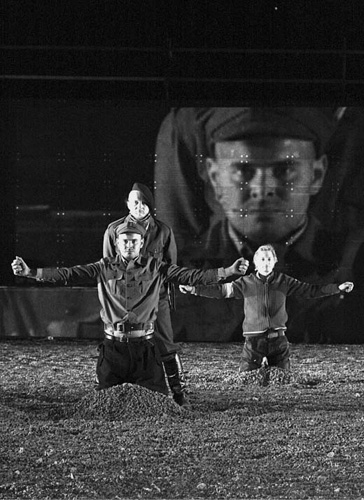

The phrase ‘to be or not to be’ was repeated three times during the production. It first appeared in a song sung by young boys in a pub, galvanizing them to fight. Then it was spoken by Hamlet himself. The third time, it was recited by young soldiers standing and falling in front of an invisible firing squad. The scenes, presenting various attitudes and convictions as equally valid, proved that Hamlet’s moral dilemma is still today a dilemma without a solution, as it juxtaposes the national tradition of a myth of devotion and heroism in the face of war with individual and very subjective feelings, fears, and desires. Hamlet’s father (seen as a monumental image projected on one of the museum’s walls) is a distinguished Polish officer who has no doubts about the response to the question, nor does he have sympathy for those who have second thoughts.

15.3. Maciej Wyczański (Hamlet) and Jan Englert (Ghost) in Hamlet’44, directed by Paweł Passini, Museum of the Warsaw Uprising, 2008. Photograph by Julia Sielicka-Jastrzębska, reproduced courtesy of the Museum of the Warsaw Uprising, Warsaw.

He does not even take into account the possibility that his son could hesitate; he focuses on explaining in detail how to fire a rifle, how to fight. Undoubtedly the father, played by Jan Englert (dressed in the same Polish officer uniform he wore in Andrzej Wajda’s Oscar-nominated 2007 film Katyń) represents the old myth of unflinching Polish heroism in an indisputably glorified struggle for independence. Polonius, unlike Hamlet’s father, represents the survival instinct. He trembles for his children’s lives, he is aware of danger and does not want them to die, even for the so-called right cause: ‘reaching for a weapon, you join the madness’ (Hamlet’44). Yet, Laertes plunges into the maelstrom of war and Ophelia also joins the insurgents. Polonius is not the only tormented parent. Gertrude explains that she married Claudius, who works for the Gestapo, only to save her son’s life, as ‘Claudius breathes for us all’ (Hamlet’44).

Hamlet’s dilemma, as well as Polonius’s and Gertrude’s decisions, provides an important perspective for looking at war, a possible new interpretive scenario. Horatio, a synonym for honour, for whom ‘to be’ means ‘to be in the war,’ presents a real ‘fragment’ of war: he introduces to the audience two elderly people, a man and a woman, real-life insurgents who tell their story on the stage. This is the most poignant fragment of the production and, as Drewniak noted in his review, for a moment the audience’s judgment is humbled; it is not theatre any more. The survivors tell stories that are tragic but somehow straightforward, simple, and unpretentious. By contrast, the characters in the play ‘really want to play their own heroic death, grow up to the role in the national drama. Bowing down like [performers] on a stage, they die – individually, in groups’ (Drewniak).

15.4. Maria Niklińska (Ophelia) and Władysław Kowalski (Polonius) in Hamlet’44, directed by Paweł Passini, Museum of the Warsaw Uprising, 2008. Photograph by Julia Sielicka-Jastrzębska, reproduced courtesy of the Museum of the Warsaw Uprising, Warsaw.

The image of the ‘real’ war becomes quite vivid with the testimony of these survivors, with the reading of the insurgents’ letters to their family, and with the descriptions of executions of civilians. This image of war recreated on stage provokes difficult questions and raises anxiety:

Real insurgents – not those who pinned the Home Army Crosses on [their own chests] in the 1990s, because there are many of those, but those who were on the barricades – were very critical of the Uprising. They had the feeling that they were a deceived generation. The civilians also felt harmed. We do not write about this, because it is not proper, it is not politically correct. (Wieczorkiewicz 9)

It may seem that the production managed to present the Polish tragedy in all its complexity and that it moved well beyond the simplistic polarity of right and wrong. Yet, the border between real life and stage was quite delicate in the performance. Telling their stories, the insurgents entered the stage as the actors of ‘The Mousetrap.’ Horatio introduced them: ‘the actors arrived.’ On the one hand, this scene destroyed the illusion of the performance; on the other hand, it forced the insurgents to be viewed through ‘a theatrical metaphor’ (Paprocka 26). The former insurgents who had attended the rehearsals also wanted the actors to dress up, ‘change into their [the insurgents’] old clothes, battledresses. To try [them] on’ (Kopciński 18). The theatrical nature of the scene was carried through at the end of Hamlet’44, which concluded with a fragment from Wyspiański’s Studium o ‘Hamlecie’ [Study of Hamlet], a bold attempt to examine and define the essence of theatre – its objectives, ideal stage, actors.16 Through these various devices, Passini also encouraged such a theatrical perspective of the Uprising itself (Mościcki).

One of the reviewers observed that this interpretation of the Warsaw Uprising is highly inappropriate because at that time people did not treat the Uprising as theatre, nor did they ‘hamletise’ – that is, philosophise or hesitate; they were not in a quandary, but did make decisions and gather up their courage (Mościcki). It is not, however, at the reconstruction of real wartime events that the production took aim. Wyspiański provides a clue: discussing his ideal theatre, he desired to revive the past by selecting details and transplanting them into the present, creating theatre that does not reconstruct or pretend, but remains a synthesis of reality. Similarly, Passini wanted his performance to encourage discussion about the ‘continuation’ of the Uprising, about its topicality. The performance was, he mentioned, an attempt to transform ‘this myth into one’s own experience’ (Kopciński 19). But perhaps the rhetoric of theatre also allows for an open interpretation, without any pretensions to truth and without imposing any judgment; the Uprising did not arouse the world’s conscience in 1944, as its leaders had hoped, but it should arouse the conscience of each individual now.

Passini used the word ‘recycling’ to refer to his production and to similar projects. He seemed to understand recycling as recovering those thoughts and concepts whose value is too obvious or customary to still influence reality today (Kopciński 18).17 By recycling both Shakespeare (refreshed by the context of current dilemmas concerning how to interpret and remember the past) and the Warsaw Uprising (retold in a new institutionalized context), the war was contemplated once again in its complexity and terror. Even if Shakespeare may not necessarily require any new reading to be understood in a contemporary context, the Uprising actually needs rereading in order to be understood at all. Hamlet’44 did not repeat the traditional ‘parochial Polish conundrum’ of whether it was right or wrong to launch the Uprising, but tried to show the everyday life of those who were there – whether by choice or by accident. Passini explained: ‘There are no Germans in this performance. Because for us the most important [thing to show] was what happens between people in the streets and those behind a curtain’ (qtd in Kraj). In order to make the war meaningful, give meaning to the event that was often seen as ‘a useless commitment, vain effort, wasted sacrifice’ (Stępień 266), one has to try to understand decisions, perhaps even dare to make some themselves – recycle history and memory, reconstitute the story.

The concept of recycling, a crucial element of postmodern culture, seems to be accepted by Shakespearean scholars, who with or without objection have to put up with modernized versions of the plays, pastiches, collages, and local appropriations. After all, as Marjorie Gar-ber observed, ‘We might say that Shakespeare is already not modern but postmodern: a simulacrum, a replicant, a montage, a bricolage. A collection of found objects repurposed as art’ (5). There is even, as Marowitz asserts writing about free adaptations of Shakespeare, ‘something culturally satisfying about toppling the idols we inherited from our forebears’ (‘Improving Shakespeare’). War, however, somehow resists this kind of rhetoric of reusing, modifying, or overthrowing the accepted interpretations. Reflecting on the past and coming to terms with the atrocities of war through recycling the themes of the Second World War arouses objections. This is because in Polish culture the concept of war and struggle is idealized; talking about war brings to the fore a myth of freedom and sacrifice indispensable to our understanding of the nation, its messianic role, and its martyr’s sufferings. Even though during the Second World War recycling, as it is literally understood, was an important element of national security – not only because it responded to the great need for materials and resources but also because it fostered a feeling of being active, useful, and motivated – the modern metaphor of reusing and salvaging implies something of a lower quality and value, waste to be recovered, something only deceptively ‘the same.’ By contrast, the tradition demands protection, demands to be unchangeable.

In times when myths are outdated, when grand narratives are assumed to no longer depict the past, when the confidence with which history is conceptualized is challenged, reconsidering war experiences becomes difficult: ‘collective mythology is a dangerous romanticism which takes away freedom from an individual and forces him to die’ (Kopciński 19). Now we do have doubts, ‘which then the insurgents probably did not have,’ explained Maciej Wyczański (the actor playing Hamlet), ‘[b]ecause I – born in 1981 – don’t know how it is to fight, be afraid of death, to take risks’ (qtd in Kraj). Thus, his Hamlet hesitates: ‘both answers are wrong. To be, that is to survive. What for? Not to be? That is to fight. In the name of what? To survive? This is a choice without choice’ (Hamlet’44). With these words, Hamlet blurs this clear meaning of a national myth. He is not an insurgent fighting for freedom; he is a contemporary, free man who wants to make an independent decision. He wants to have a choice that his father denies him.

Hamlet’s father seems to be tradition’s guardian; he is a ghost of all the soldiers/insurgents in all Polish uprisings and demands revenge for the wrong done to the whole nation. He doesn’t hesitate; Ophelia, Laertes, and Horatio follow him. In the production his monologue was reinforced and expanded with a fragment from Władysław Bełza’s patriotic poem drawn from a collection titled Catechism of a Polish Child, familiar to every Polish child. The fragment of the poem used in the performance included only the first two lines: ‘Who are you?/ I’m a little Pole.’ The audience, however, is well aware of the verses that follow: ‘What is this land?/ My motherland./ … Who are you for Poland?/ A grateful child./ What do you owe her?/ To sacrifice my life’ (Bełza 1). This poem, written before the First World War, became a part of the national myth, a source of patriotic feelings for future generations, including the Warsaw Uprising insurgents. The poem, however, complicates the interpretation of the otherwise clear voice of tradition in Hamlet’44. On the one hand, the ‘correct’ answer to the questions posed is obvious; every child, every patriot would know what to do. On the other hand, the senseless repetition of the poem’s lines (whose jingoistic meaning is presumably lost on most children preferring rhymes to sense) brings to mind this irrational drive to fight, to embrace a heroic death that adds splendour to the Polish myth of war. Perhaps it is this difficulty of not knowing, the difficulty of making independent decisions that is the main theme of Hamlet’44. Or perhaps it is the way of coping with the burden of the ‘correct’ answer that is the theme of the production. The final scene, when Horatio speaks directly to the audience convinced that the motherland is always the most important issue in one’s life, does not provide a simple solution either. Horatio’s direct message is disturbed by an image of insurgents lying dead on the ground and by the projection of the real insurgents’ names. The myth of heroic war – this helpless faith in its success, the allure of heroism – is contrasted with an ordinary fear (the desire to survive in the most physical, simple sense), but also with a fear of feeling remorse or blame (for not going to fight, for living, as well as its opposite – for going and killing). Hamlet asks Ophelia, who is eager to fight, ‘Have you ever killed a man?’ (Hamlet’44), implying that the right and just fight also causes destruction and burdens conscience.

Criticized for being ‘something like a comic book or action movie’ (Mościcki), Passini’s Hamlet’44 was actually meant to elevate the Uprising in cultural discourse. Though considered neither a very successful interpretation of Shakespeare nor a proper comment on war, the production did, however, stir ‘Polish fears, [open] wounds, prejudices, desires, expectations, phobias’ (Kopciński 20). Hamlet’44, presenting a specifically Polish national approach to war, combined the theme of war with the feelings of responsibility, guilt, and helplessness in the face of its chaos; it drew attention to the actions taken and not taken. It complicated the view of war and confused the dilemmas and problems of an individual faced with human depravity. Sixty-four years after the Warsaw Uprising, from a safe temporal distance, Passini emphasized the problems of volition and solitude; he recycled memory and myth, paid homage to national heroes and provided a space for contemplating national defeat.

With Poland’s re-entry into Western Europe, which led to the partial forsaking of the myth of Poland as a martyr and hero in favour of the vision of a common European future, such a production seems rather uncommon. A ‘Polish Prince’ has laid down arms; the play has already started to function successfully outside political allusions, focusing on its universal message and the modern globalized world, rather than on Poland’s history alone.18 The iconography of war and evil has also changed and the focus shifted from examining past experience to analysing the general concept of evil and contemporary political conflict.19 After the Nazis and Soviets, evil is now identified with terrorism and war in the Middle East. Looking at war through the prism of Shakespeare’s texts has, however, remained a potent way to deal with extreme social tensions and appalling conditions, although it is perhaps getting more difficult to present war and violence in theatre.

In the first week of the Second World War all theatres in Poland were closed. The National Theatre in Warsaw was destroyed in September 1939 and the remaining theatres through the coming years; but theatrical activity did not cease. Throughout the war, theatre, often the classics and Shakespeare in particular, continued to foster culture and lift spirits, as Krystyna Kujawińska Courtney has shown in an essay in this volume. Authors of critical and analytical texts published at that time tried to analyse the tragedy of war through the use of Shakespearean metaphors.20 Today, even more than before, directors put Shakespeare to their own uses as they see an urgent need to revive and question cultural memory, reconstitute cultural values, and voice unresolved, silenced, or new doubts and questions. To find a new role for Shakespeare in the modern world, his works have had to be recycled and reused, but (to use Michael Thompson’s term) they appear rather more durable than transient or ‘rubbish.’21 Appropriating and recycling Shakespeare anew in a specific Polish milieu ensures that the lost war – as it was for Poles22 – does not become a lost memory, that the nationally vital cultural themes such as heroic war are not melted ‘into the anonymous mass of an unrecognizable culture,’ while interpreting Shakespeare from the modern perspective of war prevents his works from ‘“(bio)degrad[ing]” in the common compost of a memory’ (Derrida 821).

1 During the seventeenth century the idea that the Polish nation played a special role in the history of Europe was presented by Wespazjan Kochowski (1633–1700), a noted historian and a poet of Polish Baroque, in his psalms. The partitions of Poland by the Russian Empire, Kingdom of Prussia and Habsburg Austria, from the eighteenth till the twentieth century, became perceived in Poland as a Polish sacrifice for the salvation of Western civilization (Prizel 41).

2 Adam Mickiewicz focused on the image of Poland as ‘a Christ of Nations’ in Books of the Polish Nation and Polish Pilgrimage. In his drama Dziady, Mickiewicz presented Poland as a martyr nation that is suffering and dying for other nations. Juliusz Słowacki, though disputing Mickiewicz’s idea of messianic devotion, also emphasized patriotism as the highest value (Kordian, 1833). Similarly, Zygmunt Krasiński focused on the problem of the enslavement of Poland and its struggle for liberation (Nie-boska komedia, 1833). Towards the end of the nineteenth century the motif of the uprising was continued by the writers who pondered on the reasons for Poland’s failure in the January Uprising (1863–5) (for example, Bolesław Prus, Lalka, 1890; Eliza Orzeszkowa, Nad Niemnem), or tried to raise the nation’s hopes for future freedom (for example, Henryk Sienkiewicz’s historical novels, Trylogia, 1884–8, Quo Vadis, 1895, and Krzyżacy, 1900). At the beginning of the twentieth century, Stanisław Wyspiański wrote one of the greatest dramas in Polish literature, Wesele (1901), in which he claimed that the Polish nation was not prepared to fight for independence. The list of literary works devoted or referring to the Polish struggle for freedom is very long and cannot be presented here.

3 All translations, if not indicated otherwise, are mine.

4 In a televised reproduction of the performance the young composition of the audience is emphasized, suggesting the continued relevance of the events of 1944 to Polish youth and the continuing institutionalization of national memory.

5 The Warsaw Uprising is sometimes confused with the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising (1943), the Jewish resistance that arose in the Warsaw Ghetto to oppose Nazi Germany’s plans concerning transportation of the ghetto population to extermination camps.

6 The number of casualties in the Warsaw Uprising is only roughly estimated by historians as no accurate documents exist in the public domain. For twenty years following the war the number of civilian causalities was considered to be 200,000, and during the 1960s, historians suggested that 250,000 civilians died, yet today they tend to agree on lower numbers, ca. 130,000 (Baliszewski).

7 In Hamlet’44 the major scenes from Shakespeare’s Hamlet (Claudius announcing his marriage to Gertrude, Hamlet meeting with the Ghost, Hamlet accusing Gertrude of betrayal, Hamlet rejecting Ophelia, the Mousetrap, and Claudius admitting his guilt) are set within the context of the Warsaw Uprising. The plot centres on Hamlet, who mourns the death of his father and becomes anxious after hearing of Claudius’s marriage to Gertrude. Though the ghost of Hamlet’s father openly asks him to avenge his death and Ophelia encourages him to fight, Hamlet remains hesitant to act and pushes both the Ghost and Ophelia away. Laertes, in contrast to Hamlet, has a very precise plan: he wants to go to battle, despite Polonius’s attempts to convince him otherwise. As the play continues, it becomes more and more focused on the theme of war and on Hamlet and Laertes’ differing responses to the wartime conflict. The play closes rather ambiguously with Horatio contemplating and defending Hamlet’s choice while projected images of marching army, tanks, and fluttering swastika flags suggest Warsaw’s capitulation.

8 See, for example, Bristol; Marsden; Krystyna Kujawińska Courtney, Królestwo na scenie: Sztuki Szekspira o historii Anglii na scenie angielskiej (łódź: łódź University Press, 1997); Krystyna Kujawińska Courtney, ‘Der polnische Prinz: Rezeption und Appropriation des Hamlet in Polen,’ Shakespeare-Jahrbuch (1995): 82–92; Kujawińska Courtney, K. and K. Kwapisz Williams, ‘“The Polish Prince”: Studies in Cultural Appropriation of Shakespeare’s Hamlet in Poland,’ Hamlet Works, ed. B.W. Kliman (www.hamletworks.org), 2009.

9 See, for example, Wolfgang G. Müller, ‘Interfigurality: A Study on the Interdependence of Literary Figures,’ Intertextuality, ed. Heinrich F. Plett (Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, 1991), especially 113–14, who draws attention to Shakespeare’s reusing of characters in various plays.

10 See, for example, Bristol; Marsden; Krystyna Kujawińska Courtney, Królestwo na scenie: Sztuki Szekspira o historii Anglii na scenie angielskiej (Łódź: Łódź University Press, 1997).

11 See also Charles Marowitz, Recycling Shakespeare (New York: Applause, 1991).

12 The Soviet Red Army was usually blamed for the failure of the Warsaw Uprising because on the first day they held positions less than ten kilometres from the Warsaw city centre but did not advance or provide promised (and expected) support to the insurgents. Therefore, during the era of Communist domination of Poland, the Warsaw Uprising was presented as a reckless and foolish endeavour that caused much damage to the country, while the soldiers of the Home Army were legally persecuted by the Communists. After the fall of Communism, historians tried to reassess the facts. Though ‘from the 1950s on, Polish propaganda depicted the soldiers of the Uprising as brave, but the officers as treacherous, reactionary, and characterized by disregard of the losses’ (Sawicki 230; Davies 521–2), the tendency was to construct and support a Warsaw Uprising cult or myth. Criticism of the Uprising was not welcome in Poland after 1989, as it was considered to continue Communist propaganda. Since then it has been unpopular (in press and academic review) to claim that the Uprising was poorly organized, with no strategic planning and, as a result, hundreds of thousands of people died and none of the military or political aims were achieved.

13 Different interpretations of Hamlet all considered the play to be a tool or weapon in the struggle against foreign oppressors and focused on Hamlet’s ambivalence and ‘existential anguish.’ Tomasz łubieński emphasized the importance of the dilemma for the Polish nation in his book on the history of Polish national uprisings, Bić się czy nie bić. O polskich powstaniach [To Fight or not to Fight: On Polish Uprisings] (Cracow: Wydawnictwo Literackie, 1978). See also Kieniewicz 347.

14 This is how Kott titled his review of the 1956 production of Hamlet by Roman Zawistowski. The review was initially published in the periodical Przegląd Kulturalny 41 (1956): 3, and later reprinted with modifications as ‘Hamlet połowy wieku’ [Hamlet of the Mid-Century] in Shakespeare Our Contemporary (72–85). For Kott, Zawistowski’s Hamlet remained the most important production of the play, very contemporary and politically meaningful. It was staged when Khrushchev presented his secret report on Stalin’s crimes during the Twentieth Congress of the Soviet Communist Party. Thus, the production symbolized the beginning of a change in the political climate: ‘At first people whispered about the crimes on the throne, later they spoke loudly’ (Kott, ‘Listy o Hamlecie’ 111).

15 See, for example, Sidorowicz; Władysław Pobóg-Malinowski, Najnowsza Historia Polityczna Polski (Warsaw: Krajowa Agencja Wydawnicza, 1990); Jan Ciechanowski, Powstanie Warszawskie (Warsaw: Państwowy Instytut Wydawniczy, 1989); Janusz Kazimierz Zawodny, Uczestnicy i świadkowie Powstania Warszawskiego – Wywiady (Warsaw: Instytut Pamięci Narodowej, 2004), and Powstanie Warszawskie w Walce i Dyplomacji (Warsaw: Instytut Pamięci Narodowej, 2005); Lech Mażewski, Powstańczy szantaż. Od Konfederacji Barskiej do stanu wojennego (Elbląg: Elbląska Oficyna Wydawnicza, 2001); Tomasz łubieński, Ani tryumf ani zgon (Warsaw: Wydawnictwo Nowy świat, 2009).

16 Wyspiański considered himself a Polish heir of Shakespeare. He rewrote Hamlet, interpreting the play in the Polish political, social, and cultural contexts. This was ‘one of the first attempts of a theatrical exegesis of Shakespeare’s text in Europe’ (Gibińska et al. 51), very influential for future Polish interpretations of the play. Additionally, his work, known as Studium o’Hamlecie’ was dedicated to ‘Polish actors’ and its aim was to provide a vision of ideal theatre that would ‘hold a mirror up to nature.’ See K. Kujawińska Courtney and K. Kwapisz Williams, ‘“The Polish Prince”: Studies in Cultural Appropriation of Shakespeare’s Hamlet in Poland,’ Hamlet Works, ed. B.W. Kliman (www.hamletworks.org), 2009; and E. Miodońska-Brookes, ‘Mam ten dar bowiem: patrzę inaczej’: Szkice o twórczości Stanisława Wyspiańskiego (Cracow: Universitas, 1997).

17 See also Agata Diduszko-Zyglewska, ‘Jestem Jak Janko Muzykant. Wywiad z Pawłem Passinim’ [I am like Janko Muzykant. Interview with Paweł Passini], Dwutygodnik. Strona kultury 5 (2009), 30 May 2009. http://www.dwutygodnik.com.pl/artykul/194-jestem-jak-janko-muzykant.html.

18 See, for example, Hamlet by Krzysztof Warlikowski (1999), Hamlet by Tomasz Mędrzak (2001), Hamlet, książe Danii [Hamlet, Prince of Denmark] by Krzysztof Kopka (2001), or łukasz Barczyk’s television theatre production of Hamlet (2004).

19 Recent Polish productions of Macbeth either horrify with scenes of intense staged violence and images of dead bodies, or present war with a game like appearance. In 2005 Macbeth dominated the Polish stage with six premieres, including productions by Andrzej Wajda, Grzegorz Jarzyna, Piotr Kruszczyński, and Maja Kleczewska.

20 See, for example, Stefania Zahorska’s article ‘“Makbet” na emigracji’ [“Macbeth” in Exile] published in London’s Wiadomości Polskie [Polish News] in 1942, or Stanisław Cat-Mackiewicz’s pamphlet ‘Lady Macbeth myje ręce’ [Lady Macbeth washes her hands], published in London in 1945.

21 In Michael Thompson’s ‘rubbish theory,’ any cultural object transforms and changes its categorization according to the functions it plays in a society and the way people react to it; it can thus be transient (entertainment), rubbish, or durable. See Thompson.

22 Following the end of the Second World War, Poland was occupied by Soviet Russia for more than fifty years, resulting in the common understanding that Poland lost the war, even though the Allies won.

Baliszewski, Dariusz. ‘Zakazana historia i zakazane liczby.’ PIO – Polityka, Internet, Opinie 13 May 2007. 20 Feb 2010. http://unicorn.ricoroco.com/nucleo/index.php?itemid=82.

Bełza, W. Katechizm polskiego dziecka. Wiersze. Lvov: n.p., 1901.

Bończa-Szabłowski, J. ‘Hamlet pełen wątpliwości.’ Rzeczpospolita 181 (2008); n.pag. 10 Aug. 2009. http://www.e-teatr.pl/pl/artykuly/58430.html.

Bristol, Michael D. Big-time Shakespeare. London, New York: Routledge, 1996.

Chrostowski, W. ‘The Suffering, Chosenness and Mission of the Polish Nation.’ Occasional Papers on Religion in Eastern Europe 10. 3 (1993). n.pag. 26 May 2010. .http://www.georgefox.edu/academics/undergrad/departments/

socswk/ree/Chrostowski_Suffering_articles_previous.pdf

Davies, Norman. Rising ‘44. The Battle for Warsaw. London: Pan Books, 2004.

Derrida, J. ‘Biodegradables: Seven Diary Fragments.’ Trans. Peggy Kamuf. Critical Inquiry 15 (Summer 1989): 812–73.

Drewniak, Ł ‘Ostatnia wódka Hamleta.’ Przekrój 34 (2008). n.pag. 10 Aug. 2010. http://www.e-teatr.pl/pl/artykuly/58962.html.

Edelman, Charles. Shakespeare’s Military Language: A Dictionary. Athlone Shakespeare Dictionary Series. London: Athlone Press, 2000.

Garber, M. Shakespeare and Modern Culture. New York: Pantheon, 2008.

Gibińska, M., et al. Szekspir. Leksykon. Cracow: Znak, 2003.

Hamlet’44. By Magdalena Fertacz and Artur Pałyga. Dir. Paweł Passini. Warsaw Uprising Museum, Warsaw. 1 Aug. 2008.

Hawkins, Gay. The Ethics of Waste: How We Relate to Rubbish. Lanham: Rowman and Litttlefield, 2006.

Kendall, Tina, and Kristin Koster. ‘Critical Approaches to Cultural Recycling: Introduction.’ Other Voices 3.1 (May 2007): n.pag. 10 Feb 2010. http://www.othervoices.org/3.1/guesteditors/index.php.

Kieniewicz, S. Historyk a świadomość narodowa. Warsaw: Czytelnik, 1982.

Kopciński, J. ‘Robimy powstanie!’ Teatr 10 (2008): 18–22.

Kott, J. ‘Listy o Hamlecie.’ Kamienny potok. Szkice. Warsaw: Nowa, 1981.

– Szekspir współczesny (1965). Cracow: Wydawnictwo Literackie, 1997.

Kraj, I. ‘Wszyscy jesteśmy Hamletami.’ Rzeczpospolita 179 (2008): n.pag. 10 Aug. 2009. http://www.e-teatr.pl/pl/artykuly/58388.html.

Marowitz, Charles. ‘Improving Shakespeare.’ Swans Commentary 10 April 2006. 17 Feb. 2010. http://www.swans.com/library/art12/cmarow43.html.

– ed. The Marowitz Shakespeare: Adaptations and Collages of Hamlet, Macbeth, The Taming of the Shrew, Measure for Measure, and The Merchant of Venice. New York: Drama Book Specialists, 1978.

Marsden, Jean. The Re-imagined Text: Shakespeare, Adaptation, and Eighteenth-Century Literary Theory. Lexington, Kentucky: University Press of Kentucky, 1995.

Mościcki, T. ‘Rocznicowe głupstwa zamiast hołdu.’ Dziennik 183 (2008): n.pag. 10 Aug. 2009. http://www.e-teatr.pl/pl/artykuly/58481.html.

‘Odczytać Powstanie.’ Kultura polska: Portal kultury polskiej. Instytut Adama Mickiewicza. 27 July – 10 Aug. 2008. 14 May 2010. http://www.culture.pl/pl/culture/artykuly/wy_in_odczytac_powstanie_2008.

Paprocka, K. ‘Powstanie Tu i Teraz. Wywiad z P. Passinim.’ Teatr 10 (2008): 23–7.

‘Powstańcy u Szekspira.’ Raporty. 64. rocznica Powstania Warszawskiego. Portal TVN24.pl. 1 Aug. 2008. 10 Aug. 2009. http://www.e-teatr.pl/pl/artykuly/58410.html.

Prizel, I. National Identity and Foreign Policy: Nationalism and Leadership in Poland. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998.

Sawicki, J.Z. Bitwa o prawdę: Historia zmagań o pamieć Powstania Warszawskiego 1944–1989. Warsaw: Wydawnictwo ‘DiG,’ 2005.

Sidorowicz, J, ed. Kulisy Katastrofy Powstania Warszawskiego 1944. Wybrane Publikacje i Dokumenty. New York: Nieformalna grupa b. Powstańców Warszawskich, 2009.

Stępień, M. ‘Największe nieszczęście i wyraźna zbrodnia.’ Kulisy Katastrofy Powstania Warszawskiego 1944. Wybrane Publikacje i Dokumenty. Ed. Jan Sidorowicz. New York: Nieformalna grupa b. Powstańców Warszawskich, 2009. 261–6.

Sugiera, M. Upiory i inne potwory. Pamięć-historia-dramat. Cracow: Księgarnia Akademicka, 2006.

Sułkowski, B. Hamletyzowanie nasze: socjologia sztuki, polityki i codziennosci. Łódź: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu łódzkiego, 1993.

Thompson, M. Rubbish Theory: The Creation and Destruction of Value. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1979.

Trznadel, J. Polski Hamlet. Kłopoty z działaniem. Paris: Libella, 1988.

Wieczorkiewicz, P. Interview by Rafał Jabłoński. ‘Obłąkana koncepcja Powstania.’ Sidorowicz 7–14.

Wyspiański, S. The Tragicall Historie of ‘Hamlet,’ Prince of Denmarke, By William Shakespeare. Wedlug tekstu Jozefa Paszkowskiego, swiezo przeczytana i przemyslana przez St. Wyspianskiego. Cracow: Drukarnia Uniwersytetu Jagiellonskiego, 1905.

Zamoyski, A. ‘Solving the Polish conundrum. Rising ‘44: The Battle for Warsaw by Norman Davies.’ The Spectator 1 Nov. 2003. 10 Aug. 2009. http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_qa3724/is_200311/ai_n9331048/.