ELEVEN

LOS ANGELES

DURING THEIR TIME IN THE BRONX, THE INTERNATIONAL SUBMARINE BAND never complained about Gram’s willingness to work or his commitment to the band. He wrote constantly, rehearsed hard, and played their many sets with dedication. Gram’s time in Los Angeles would be marked by periods of passivity, a disinclination to rehearse, pissed-off band members who regarded Gram as a lazy prima donna, and canceled gigs. Gram would have periods of intense commitment in L.A., but they were not the norm.

Gram’s hard work in New York might have sprung from the excitement he felt being in a community of great players, living and working full-time with a real band. Youthful enthusiasm doesn’t provide a sufficient explanation, because Gram didn’t outlive his youth by much. The obvious culprit in Gram’s eroding work ethic would seem to be drugs. In New York, Gram had smoked a lot of pot, dropped a disputed amount of acid, and spent the odd afternoon puffing cow tranks and rolling on the floor. In L.A. he would discover barbiturates and heroin. While on those, he never worked with the drive he showed in New York.

The band’s fast start in California seemed to augur well. Their new booking agent, Ronnie Herrin, placed them in prestigious opening slots in Long Beach, the L.A. Palladium, and clubs in Southern California. The ISB packed their gear in a van and drove from gig to gig. They opened for the Doors, those darlings of the Sunset Strip, whose first album had just been released in January 1967. They opened for Iron Butterfly, whose “In-A-Gadda-Da-Vida” wouldn’t be released until 1968, when it would spend eighty-one weeks in the top ten. The Butterfly were the quintessence of a jamming band; “In-A-Gadda” et cetera, all seventeen minutes of it, took up the whole first side of their second LP. Together with the amped-up English blues band Cream, the Butterfly could be held responsible for the plague of drum solos inflicted on concert crowds for the next seven years. Their onstage ramblings provided an extreme contrast to the ISB’s three-minute version of “Buckaroo.”

The International Submarine Band, newly arrived in L.A.: Ian Dunlop, John Nuese, Gram Parsons, Mickey Gauvin. (Courtesy Marcia Katz)

As the ISB opened for successful bands with clear-cut identities and crafted stage shows, they were coming undone. In New York the band worked well together. Their separate Los Angeles lives ate into rehearsal time and gave rise to an indulgence that did them no good.

One night they opened for Love at a two-thousand-seat arena in the San Fernando Valley. Love’s single “Seven & Seven Is,” had reached number thirty-three but the band had a far-reaching influence not represented by its chart position and performed tight, well-written songs. For their part, the ISB gave a hysterically disjointed performance that demonstrated the fissures opening within the group. Their set began with the usual repertoire of Buck Owens, a couple of Gram originals, “Six Days on the Road,” and soul covers. Then the band branched into a disastrously free-form jam. Gram played organ. In addition to his drums, Mickey had a theremin, an early electronic instrument played by moving one’s hands between two antennae, creating an eerie ululation most readily associated with soundtracks from low-budget fifties sci-fi movies. As the music unfolded, bereft of any structure, Ian assembled a sculpture onstage. The theremin jam and sculpture erection evoke a scene out of Spinal Tap. Drug-fueled misunderstanding and bad judgment might be the explanation, but Ian Dunlop painted the show as an earnest effort to stretch out—and a reflection of diverging interests. “While it could have been an interesting departure,” Ian reflects, “it underscored the dispersal of the band.”

The ISB was losing momentum. The boys rehearsed less frequently and, when they got together, tended to jam rather than polish their songs. They would set up and play casually at Brandon’s house in Topanga Canyon, where Peter Fonda was a regular visitor. Life in the Bronx house had hardly been monastic. It came to seem rigorously focused compared to the temptations of L.A.

Fonda became a countercultural star for his role as the sensitive Hell’s Angel leader Heavenly Blues in Roger Corman’s 1966 biker-exploitation drive-in movie classic The Wild Angels. Featuring episodes adapted from Hunter S. Thompson’s Hell’s Angels: A Strange and Terrible Saga, Corman’s film costarred Nancy Sinatra, Bruce Dern, and several members of the Hell’s Angels San Bernardino and Oakland chapters.

Fonda’s portrayal of the conflicted, violent-yet-poetic Blues produced the first true counterculture movie hero. Blues is a sixties update of the macho cowboys and tough warriors of the post–World War II era. Wild Angels set up Fonda’s starring role in the Dennis Hopper–directed (and Fonda-financed) Easy Rider three years later. Easy Rider grossed a hundred million dollars and, like the 1969 Woodstock music festival, demonstrated the shocking market power the counterculture possessed. More than the Beatles, it was Easy Rider that taught Middle America how grossly uncool it was to not have long hair, to not smoke marijuana, and to not be nice to hippies. Easy Rider is only one example of the artifacts tossed off by the originators of sixties aesthetics and style that were seized by the slow-moving mass market as beacons lighting a new road. While the masses embraced these new archetypes, the originals who created them had already moved on, hunkered down, burnt out, or cashed in.

Fonda met Gram when he was starring in Roger Corman’s LSD film The Trip. The screenplay, credited to another Corman regular, Jack Nicholson (though Corman did not shoot Nicholson’s script), sought to re-create the experience of an LSD trip. The Trip reflected Corman and Fonda’s evangelistic fervor about the drug. Fonda had taken acid with the Beatles and told them of a childhood near-death experience, repeating, “I know what it’s like to be dead.” The Beatles re-created that conversation in “She Said, She Said” on their album Revolver.

The movie star and the musician hit it off—“Gram was kind, and that’s a rare quality,” Fonda said—and Fonda featured Gram’s band in The Trip, putting them onstage in a scene shot in a club. Gram wears a turtleneck and jeans. He lip-syncs to the music of the Electric Flag, an all-star psychedelic blues band featuring guitarist Michael Bloomfield, drummer Buddy Miles, and keyboardist Barry Goldberg, who would later write songs with Gram. “I wanted to give the ISB any exposure I could,” Fonda continued. “John Nuese was a fine guitarist and Mickey was a hell of a drummer. A fast foot—that boy had a fast foot.”

Gram paid for a Sub Band recording session at Gold Star Studios in Hollywood. The ISB cut Gram’s original composition “Lazy Days.” Featuring the driving cut-shuffle beat that Gram picked up from the Bakersfield sound, it’s a witty seduction song, with Gram promising, “I think I’ll teach you how to relax.” The lyrics also reflect Gram’s emerging comfort with life in L.A.

“Lazy Days” was intended for The Trip. Roger Corman rejected the song as “not acid enough.” Fonda was more taken with Gram’s “November Nights,” the “Bach-ian,” Beatlesesque folk number he’d recorded at Jim Carlton’s house. A wordy, rueful look back at a former love, “Nights” reflects Gram’s early inspirations (Dylan and the Beatles, mostly). The best moments foreshadow Gram’s mature, harrowing, confessional songs. In the song’s most personal lines, Gram sings, “You think you were taken for granted / You’re probably right.”

Fonda told Gram it was terrific. “He taught me to play it,” Fonda said. “I practiced and practiced and practiced. Then I went out and cut it. Gram was thrilled.” Fonda’s producer was the black South African expatriate jazz trumpet player Hugh Masekela. Best known for his instrumental hit single “Grazing in the Grass,” Masekela was perhaps not the first choice that comes to mind to produce a strummed-guitar folk song. Masekela had also produced the “Lazy Days” sessions, so he was at least acquainted with Gram’s music.

Fonda recorded with Masekela on trumpet and a standard four-piece backup band. Masekela’s label, Chisa Records, released the single with a B-side of Fonda singing Donovan’s “Catch the Wind.” It’s an astute pairing on Fonda’s part: “November Nights” has a certain Donovan feel. The record never got any airplay nor made a dent in anyone’s attention span at the time.

Gram was pulled away from the band by the time he spent with Nancy exploring their shared spiritual interests. “She opened spiritual doors for him that words could not provide,” Marcia Katz says. “He was so thirsty. He was seeking inner knowledge and higher thought. The two came together not just as soul mates but as spiritual beings that had come from some other higher place. They knew each other well. They were as kindred and of like kind as you could get.”

Gram and Nancy, at this stage in their relationship, spoke of one another in precisely those terms. They briefly attended Scientology meetings. Both also became intrigued by a spiritual movement known as Subud, founded in the twenties by an Indonesian guru, Muhammad Subuh Sumohadiwidjojo, and introduced to the West in the late fifties. It focuses on an experience of surrendering completely to the divine rather than on specific religious dogma. Roger McGuinn, cofounder and leader of the Byrds, was an avid follower. Adherents of Subud hold that changing one’s name can be an aspect of spiritual development; McGuinn changed his first name from Jim to Roger at the urging of his Subud guru, who believed a name starting with R would “vibrate better in the cosmos.” Much later in life, McGuinn became a devout Christian.

Gram’s Harvard advisor, Jet Thomas, also moved to Southern California. He attended Pomona College, doing postgraduate work in Heidegger, Wittgenstein, and the philosophy of language. “Gram got me to go with him to this Subud guru guy,” Jet says. “It was a quasi-Hindu thing. I don’t think it was dangerous. It was a little sect personality group around this person. We talked about it afterwards, but Gram was smart and had a good sense of skepticism. He would flirt with these things and had interest in them, but he never got involved with them.”

Gram burrowed deeper into his relationship with Nancy and pursued other interests. The ISB became less of a priority. “After the initial activity and getting gigs, things tailed off,” Ian says. “We were meeting with A&R people trying to get a deal. We weren’t doing much writing. Record people would occasionally come to gigs, but they didn’t want to take a chance on us. We stagnated. Not getting an opportunity definitely wore on us. I wanted to do more than sit around and wait.”

The problem wasn’t that Gram lived separately from the band or that he was in love. He also lived in a different economic reality. Despite the financial difficulties of the Snivelys, Gram’s portion of the Snively trust was intact. Though the figures are in dispute, Gram most likely received around thirty to forty thousand dollars, two times a year—a fortune in 1967. Gram never had to earn. If he wanted to let music slip to focus on love or spiritualism, he would eat no worse. That was not true for the rest of the band.

BILLY BRIGGS AND BARRY TASHIAN followed the ISB to L.A. With the band in disarray, Mickey and Ian regularly rehearsed with the two former Remains. They shared an interest in Fats Domino and what Billy describes as “rocking out.” After a successful audition at the Topanga Corral, a watering hole for long-haired musicians and their crowd, the four began to play more often than the ISB. Gram sometimes joined them onstage. So did a collection of Topanga music luminaries including Taj Mahal guitarist Jesse Ed Davis and legendary saxophone player Bobby Keys. Once a member of Buddy Holly’s touring band, Keys would later play with Joe Cocker’s Mad Dogs & Englishmen and with the Rolling Stones on Sticky Fingers and Exile on Main Street. Keys played with a singular, ripping tone and was as famous for his prodigious appetite for liquor, drugs, and hell-raising as for his music. As required of anyone who hung with the Stones year after year, Keys was gifted with an apparently indestructible constitution. As of 2007, he was still touring with the band.

The most luminous of L.A. luminaries joining the band onstage was pianist, guitarist, and songwriter Leon Russell. Russell is an intersection unto himself in rock’s history: Many other artists’ careers pass through his. He studied guitar under James Burton (Elvis’ guitarist, Gram’s future guitarist, and a legendary player), produced hits for Gary Lewis and the Playboys (Russell’s band played all the instruments on Lewis’ hits), and was part of the famed Wrecking Crew, the collation of L.A. studio musicians who provided music for Phil Spector, Brian Wilson of the Beach Boys, the Byrds, and the Mamas & the Papas among hundreds of others. Russell played on hits as diverse as Ike & Tina Turner’s Phil Spector–produced “River Deep, Mountain High,” the Byrds’ “Mr. Tambourine Man,” and Herb Alpert’s “A Taste of Honey.” Russell wrote “Superstar,” a number one hit for the Carpenters; formed Joe Cocker’s band Mad Dogs & Englishmen, led the band, and starred in the movie of their tour; recorded two influential records of Southern, gospel-inflected rock in 1970 (Leon Russell ) and 1971 (Leon Russell and the Shelter People); appeared onstage and in the film of George Harrison’s all-star Concert for Bangla Desh; and wrote “This Masquerade,” which soft-jazz guitarist George Benson took to number one in pop, dance, and R&B.

Russell was also responsible for the Shindogs, the house band for ABC’s weekly rock showcase, Shindig! Their lineup included guitarist James Burton, Elvis’ keyboardist and arranger Glenn D. Hardin, bassist Joey Cooper, and drummer Chuck Blackwell. Burton and Hardin would later play with Gram, Blackwell would tour with Russell and Cocker in Mad Dogs & Englishmen. Also in the lineup was guitarist and singer Delaney Bramlett. Delaney, a white Southern blues-gospel-country shouter, pursued, in his own chaotic, random way, the synthesis of American roots that Gram would later call Cosmic American Music. Delaney had an in-depth knowledge and repertoire of blues, traditional country, mountain folk music, gospel, and rock. Eric Clapton fell in with Delaney—for better or worse, Delaney’s credited with convincing Clapton to sing—and toured with him and his wife, Bonnie. Clapton was in search of musical roots that, as an Englishman, he felt he did not possess. The core of Delaney’s band, and of Russell’s, went on to back up Eric Clapton on his Layla sessions as Derek and the Dominos.

Leon Russell incarnates key ideas of Gram’s Cosmic American Music. He was a one-man melting pot, playing commercial pop, country, white roots, R&B, and his signature original sound, which owes much to Jerry Lee Lewis, Oklahoma church music, and the L.A. studio obsession with killer chops and sellable pop structure. The power and breadth of Gram’s influence on American commercial and underground music took years to mature. In the late sixties and early seventies, Leon Russell was California-white, commercial pop.

Russell taking the stage with Billy and Barry and Mickey and Ian at the Corral gave them instant credibility. His presence also speaks to how well they played.

The new group felt the need of a handle and, following the disaster of the name the International Submarine Band, came up with something even worse: the Flying Burrito Brothers. Both Billy Briggs and Ian Dunlop take credit. “We went to some funky Mexican restaurant-stall place in the Valley,” Ian says, “and I said, ‘Look, let’s go out and do some gigs and we’ll call the band, I don’t know, anything—the Flying Burrito Brothers.’ I said it just like that.”

“Ian will tell you that he invented the name the Flying Burrito Brothers,” Billy says. “But I invented the name, and the way I can prove it is that handwritten on the back of this poster for the Topanga Corral I have all the permutations of the possible ways to have it”—Flying this and Brothers that. “I finally came up with Flying Burrito Brothers. Maybe Ian thought of the word burrito.”

At times the band called itself something even sillier, as bad a name as the annals of rock provide. According to John Einarson’s Desperados, they occasionally gigged as the Remains of the International Main Street Flying Burrito Brothers Blues Band. By that standard, the Flying Burrito Brothers is a masterpiece of branding.

The Burrito Brothers played comedy material, western swing, older rock and roll, soul, and country. “Suddenly Mickey and I were busy,” Ian says. “We were doing gigs, and the other thing seemed to be floundering or had gone a bit stale.”

Gram sometimes sang with them and played guitar when they played country. He began to woodshed with Barry Goldberg, one of the pioneers in the early-sixties movement of white musicians playing the Chicago and Detroit style of amplified blues. This represented a departure from the folkie movement of re-creating Delta or acoustic blues. The Chicago sound was urban, hard-edged, and raw. Exemplified in its original form by Howling Wolf, Sonny Boy Williamson, Muddy Waters, pianist Otis Spann, and harmonica player Little Walter, it was an inspiration for the Rolling Stones among countless others. Goldberg played piano and organ with Charlie Musselwhite, a white blues harmonica player who modeled his style on Little Walter’s, and can be heard on Stand Back!, Musselwhite’s best record. Goldberg also played with Michael Bloomfield and the Paul Butterfield Blues Band. Gram and Goldberg tinkered around and together wrote “Do You Know How It Feels to Be Lonesome?”

Fred Neil came to town and stayed at Denny Doherty’s house. Denny had been a member of the Village folk group the Mugwumps with Cass Elliot and Lovin’ Spoonful cofounder Zal Yanovsky. Denny hit it big with Cass as half of the Mamas & the Papas. Gram visited Fred Neil at Denny’s and there met Bob Buchanan, an old-school folkie who’d played with the New Christy Minstrels. “Whenever you go to Fred’s,” Bob Buchanan says, “there are guitars out. Gram had his and of course I had mine. Gram and I figured out that we had the Everly Brothers in common. It was a marriage made in heaven.”

Bob describes Gram at that time as “a pretty mellow fellow,” but with a lot of presence. “He was casual—he’d wear slacks and a button-down shirt, shoes and no socks. He held himself when he was out and about like he was a commanding kind of guy. He wasn’t shy, he was sure of himself. He knew who he was and he knew he had an agenda. We weren’t sure what it was, but Gram was unto himself. That was his agenda.”

Gram was searching out the context of the music that attracted and intrigued him. That meant heading into a nightlife that other musicians of his age and milieu avoided. Gram and Bob played impromptu gigs at the Corral and the Palomino in North Hollywood. The Palomino was a country bar, a redneck dive. Gram and Bob showed up for open-microphone talent nights; their repertoire included George Jones, Buck Owens, and Everly Brothers covers. They played or hung out at the Bandera on Ventura Boulevard when Delaney Bramlett had a regular gig there, the Rag Doll in North Hollywood, the Corncrib in Monrovia, and others.

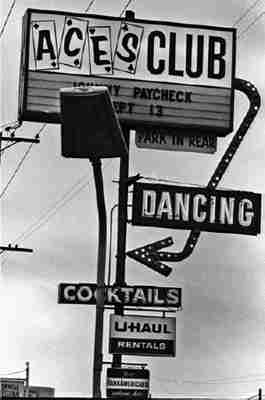

A favorite was the Aces in City of Industry, a louche industrial zone next to Los Angeles. It was the site of a jam session that pianist Earl Ball had originally run as an all-night, Friday-evening-to-Saturday-morning party at Okieville, a country bar in Fontana, home of the original chapter of the Hell’s Angels. “All those people doing all that speed needed someplace to go,” Earl Ball says. “And there were a lot of Okies and Arkies that liked to party late.” When Okieville shut down in 1967, Ball’s jam moved to the Aces.

It took courage for Gram to venture into country bars like the Aces. They were cultural enclaves—ghettos—in which the lines were clearly drawn: hippies on one side (suburban, likely middle-class, long-haired, dilettantes when it came to country music, anti-Vietnam, and pro-marijuana) and non-hippies on the other (working-class, defiantly short-haired, devoted to country music, likely veterans or self-anointed patriots, drinkers, and amphetamine users). In 1967, the relative rarity of long hair meant that anyone who dressed a certain way was automatically an ally. “If you played in a blues or a psychedelic or an English rock band,” David Barry says, “you had long hair and you were a hippie. You walk into a psychedelic club and everybody likes you because you were a hippie. Period. You listen to FM radio, you’ve got underground newspapers, you read Rolling Stone. You were hermetically in your own cultural universe—you could live in and work in it, at least in a few big cities.

The Aces after-hours club. (© Andee Nathanson, www.andeenathanson.com)

“And that was not true if you were into country music. If you were a hippie, you walked into a scene out of Easy Rider every time you wanted to play.”

In 1967, longhairs who stepped outside their own milieu could look forward to verbal and often physical harassment. In a noisy drunken room where hippies were rare, hostilities were more likely to surface. Gram was undaunted; he had been venturing into forbidden places since he went into black Winter Haven looking to buy liquor. He and Bob competed in the Thursday-night talent shows at the Palomino. Contestants would sing a song of their choice backed by the steel guitarist (and guitar technology innovator) Red Rhodes and his band, the Detours. Rhodes could play: The Country Music Association voted him Steel Guitar Player of the Year from 1965 through 1968. He played on Elvis Presley’s records and joined the Wrecking Crew when they needed a pedal steel. It speaks to the enclosed world of country music and to the status of the Palomino that a musician of Red Rhodes’ reputation and influence would run a house band.

Pedal-steel player Jay Dee Maness had played in the house band at Okieville until it closed. He occasionally sat in with the Detours at Palomino’s. “Talent night at the Palomino was always Thursday nights,” Jay Dee remembers. “Anybody who wanted to sing or play would sign a list up to a certain number. Many of the same people showed up every week. The MC would go, ‘Let’s hear it for so and so, come on up!’ and they’d do one song only. Usually it was average or horrible. People didn’t have good timing, and the band got to where we could follow them no matter where they came in or out of a song. That was our challenge. So talent night was popular, especially with the musicians.”

“Gram usually went in a T-shirt, a pair of jeans, and slightly long hair,” Bob Buchanan says. “My hair was longer. So they thought we were from over the hills in Hollywood—that we were the enemy. We’d always come in second to the guy in the wheelchair who did Johnny Cash impersonations.

“Gram kept going out there after I stopped. He got into a fight with some Marines and got his ass whupped. Gram couldn’t keep his mouth shut, even in the wrong situation.”

In a last attempt to hold together, the ISB cut a demo. Gram financed the sessions, hoping to emerge with product he could take to record labels. The band cut six songs at Gold Star Studio. “We recorded a mixed bag that was heavier, with not so much country,” Ian Dunlop says. “Gram played a big Hammond organ. We had a big, fat sound. I sang ‘Hooked,’ a slightly obscure Bobby Marchan number, and Gram sang a more bluesy soul thing, a cover of Little Milton’s ‘Feel So Bad.’ It was a good session. It was full of energy, with little angst. There wasn’t anything at risk, wasn’t any anticipation of disappointment. It was good fun.”

L.A. scenester Suzi Jane Hokom heard about the band. After producing Kitchen Sink, a band from Amarillo, Texas, Suzi was looking for another project. She was well connected: Her boyfriend was the producer, arranger, songwriter, and hit maker Lee Hazlewood. A tough-ass Texan who’d written songs and produced for a number of smaller pop acts, Hazlewood built his reputation working with seminal guitar twanger Duane Eddy. In 1966 Hazlewood hit the big time by writing and producing the Nancy Sinatra smash “These Boots Are Made for Walkin’.”

Suzi convinced Hazlewood to sign the Sub Band to his Lee Hazlewood Industries label. Gram’s dealings with Hazlewood would produce nothing but trouble: Being the pet project of a powerful man’s girlfriend seldom proves a good career move. The upside was that Hazlewood came from Texas, knew country and hillbilly music, and was rolling in money and clout from his Nancy Sinatra hits. The downside was that Lee Hazlewood International was not RCA or Columbia.

Ian Dunlop wasn’t happy: “The ISB seemed to be floundering. We had interest from major labels and none of them panned out. Signing with Lee Hazlewood happened because the big-league labels passed. Gram was full of frustration. He was a big fish in a small pond in Florida. He showed so much promise and expected to get somewhere faster. Now we were doing a deal with LHI [Lee Hazlewood Industries] and making a country album? Lee Hazlewood didn’t sound interesting or adventurous to me. I was the only one who felt that way. That’s when I decided it wasn’t working.”

In June 1967, Ian officially departed from the International Submarine Band. He wanted to focus on the Flying Burrito Brothers, and Mickey Gauvin went with him. Their repertoire swung back to Mickey’s roots: soul music. They added a horn section and gigged like mad.

Ian and Mickey did not play on the ISB’s LHI sessions in July. John Nuese stuck with Gram’s vision: “Gram and myself felt country music was the thing to do.” He also found much to like about the L.A. lifestyle. “It was a different era,” he says. “It was the age of free love. The male-female relationship criteria were considerably different than they are now. At Shady Grove, Peter Tork’s estate [Tork was a Monkee and nationwide teen heartthrob], I lived in the pool house by this huge swimming pool. Every morning I’d get up by nine o’clock, and there’d already be eight or ten naked women sunning themselves at the pool. Every single woman that came to Peter’s estate eventually took off her clothes. Brandon [De Wilde] and I would take bets. ‘I’ll give her ten minutes, I’ll give her half an hour…’ Women in those days in that era wanted to show off their bodies, and they were beautiful. There hasn’t been anything like the sixties in California, with the love-ins and everyone getting high. This was similar to the promiscuity of the 1920s. The sixties were even possibly more pronounced. The age of free love.”

GRAM SIGNED WITH Brandon De Wilde’s manager, Larry Spector. Spector was pure Hollywood, with a pure-Hollywood career history. His mother had been Dennis Hopper’s bookkeeper. Hopper had a meeting at 20th Century Fox and felt vulnerable showing up without an agent or manager—so he ordered Spector into a suit and took him along as a prop. As could only happen in L.A., Spector parlayed his propdom into an actual career as a manager. Byrd David Crosby was Spector’s entrée; Crosby then introduced Spector to Peter Fonda, Brandon De Wilde, and other members of the Byrds. Byrds manager Jim Dickson quotes Hopper saying of Spector: “His only asset was a college education and that his mother was a bookkeeper. He winged it constantly and didn’t know anything about the business at all.”

Spector is remembered as an operator’s operator. He was a master of paperwork transfers, mysterious mortgages, providing assets without fronting cash yet still finding a way to take a cut. He shifted his clients from one house to another, from one car to another. When one client moved up to a Porsche, a less successful client would end up with his cast-off Pontiac. “Something happened with Bob Denver,” Ian Dunlop says, referring to the actor who played Gilligan on the hit TV series Gilligan’s Island. “He either got richer or poorer. Larry Spector got Brandon to take over Denver’s house in Topanga Canyon. That was the Wave View Drive house. It was your classic L.A. house with an empty swimming pool. It came complete with Berber rugs and pseudo-Kline paintings. All that shit stayed in the house. Denver out, Brandon in.”

Bob Buchanan moved into an apartment in the Sweetzer Avenue complex, where Gram was living with Nancy. “Gram and I were often at his or my place playing Everly Brothers, George Jones, and Buck Owens,” Bob says. “Gram wasn’t doing any folk music. Not one folk song. Not one protest song. Nothing. And when it came to Buck Owens, or George Jones, I was lost. I never listened to that as a kid. I was totally in love with it: the sincerity and the heartbreak. We were jamming on that and Gram says, ‘We’re getting a band together.’”

In Desperados, John Nuese tells Einarson, “Our approach to country music was from a rock end of things. We weren’t like a bunch of rednecks from Dixie, straight arrows with a quarter inch of hair. We were longhairs playing country music, so from that angle it was new to the longhair audience. It took a little bit of acclimating to, but once they heard it they got into it and liked it. To our knowledge, we were the only people playing hardcore country around L.A. at that time.”

Gram took Nancy for a visit to Winter Haven. Gram went fishing with the husband of his cousin Martha Snively, and insisted Martha cook Southern dishes including the traditional New Year’s Day good-luck meal, hoppin’ John, a mixture of rice, ham hocks, and black-eyed peas. Gram played piano, organ, and guitar at the Snively big house.

Martha thought Gram and Nancy “seemed to be in love. Not the huggy-kissy kind of love, but our family was not that way. We were not outwardly affectionate.” Gram’s friend Jim Carlton wasn’t so sure. “Nancy was a lovely woman, beautiful,” he says. “Over and over she and Gram said, ‘Marriage is a piece of paper you don’t need,’ et cetera, et cetera. But it felt like game playing. Gram wasn’t ready—he was twenty-one. Nancy was smart, but they were both too young for any kind of marital relationship, to settle down and have kids. Nancy was glamorous, and they were into the glamour and the rock and roll of it. She was sophisticated about their relationship, in the sense that Gram was certainly not faithful to her. Gram said, ‘Aw, we’re past all the cheap physical stuff.’

“I didn’t get the feeling he was that attached to her. He was fooling around with anyone he could at the time. Love the one you’re with, that kind of thing. He liked having her around when there was no one else, ’cause she was a gorgeous woman. She was lovely, but she was like those gals on album covers—just beautiful women, ornaments.

“Nancy was into him, but every woman he ever met was into him. Women found him attractive. Always did. And you look at him, he’s not a great-looking guy. He doesn’t have classic features. But you put all the pieces together and whatever that synergy is, he certainly made it work.”

Jim joined Nancy and Gram at the Snively mansion. “We were at the big house all alone,” Jim says. “The family had gone, so we were hanging there for a long weekend, doing acid. Gram was entranced by Ringo’s version of ‘With a Little Help from My Friends.’ He played it incessantly. He loved the song, he loved the version, he loved the feel. And he had that record on the turntable constantly, that one cut.”

After Nancy left, Gram and Carlton went to breakfast in Cypress Gardens. As they walked out of the restaurant, the waitress came running with Gram’s sunglasses, which he’d left at their table. Gram told her: “You’re a very nice country lady.” He showed the glasses to Carlton. “They were the sunglasses Fonda wore in The Wild Angels,” Jim says. “Gram got custody of them. They were a gift from Fonda and Gram was proud of them. Of course, he wouldn’t announce it. It had to come up in conversation.”

Jim recalls that Gram talked a lot about his new movie-star friend, however. “He brought home this grass called Icebag that Fonda kept buried in his yard. It was smuggled into the States in ice bags and was legendary smoke back then.”

Jim and Gram frequented a Winter Haven lounge where Buddy Canova played. Gram got up to sing, and someone insisted he do “I Left My Heart in San Francisco.” Gram stumbled through it, then followed up with a rendition of Porter Wagoner’s “A Satisfied Mind” that brought down the house. Afterward at the lounge, Gram bragged to his high school friends that he was making a hundred dollars a day in Los Angeles as a session musician. No one but Jim Carlton knew enough about the music business to contradict him, and Jim let it pass.

While Gram went to call Nancy long-distance, a waitress approached Jim to ask if acquaintances of his across the bar were old enough to drink. Carlton shook his head, meaning he didn’t know one way or the other. The acquaintances, who couldn’t hear the exchange, took Carlton’s gesture to mean that he’d snitched them out to the waitress.

“Somebody onstage asked, ‘Where’s Gram? Will he come sing a song?’” Carlton says. “I said, ‘I’ll go get him.’ These guys followed and ambushed me. I knocked on Gram’s phone booth and said, ‘They want you to sing another.’ I turned around and one of these guys got me right in the neck with his fist. My glasses flew off and fell over this balcony down by the pool and I could not see. I yelled to Gram and he came out and the two of us took care of those guys. It was great. Gram had no qualms about jumping in and getting hurt. There wasn’t any of his pretty-boy crap. He could have gotten his teeth knocked out. So we took care of them, and Gram went down to retrieve my glasses. It was like the cavalry showed up…. Somebody told the manager, and he wanted to get the police. We were like, ‘No, no, no,’ ’cause we were underage, too.”

This fight contradicts the persistent “rich pussy” stories that paint Gram as a tough-guy poseur. Such talk originated among Gram’s more macho Winter Haven former bandmates. On the scale of redneck fighting men, Gram may not have been number one, but that didn’t automatically make him a “rich pussy.” Later, when Gram began to ride motorcycles that he could not handle, his harder-core motorcycle buddies in L.A. would resurrect the phrase.

Jim saw firsthand how Gram financed his lifestyle. “One night Gram told me, ‘You don’t know that I have this fund.’ He had collected his stipend and had thirty or forty thousand dollars laid out on the bed,” Jim recalls. “I didn’t know what to say…I was terribly broke. I had a ’57 Ford that needed a battery. I had to leave it running in the parking lot so it wouldn’t quit on me. Gram handed me twenty dollars and says, ‘Go buy a battery.’

“And every day he’d buy lunch. Paige was one of the Snively family secretaries. She’d drop by every day and bring a bond, a matured savings bond from way back when. Gram would buy lunch with that. I’d say, ‘Well, jeez, thanks for lunch,’ and he’d say, ‘Don’t worry about it. It’s on some old relative.’ Gram had little hundred-, two-hundred-, five-hundred-dollar bonds, whatever, they were rolling in…. Chump change in addition to his stipend from the trust fund.”

While Gram was in Winter Haven, Bob Buchanan was in Coconut Grove, recording with Fred Neil. Gram visited them in the Grove and brought Bob back to Winter Haven. The two took a train from Winter Haven to Chicago, where Bob gave Gram a tour of Chicago’s folk scene. They rode the Sante Fe Chief from Chicago back to Los Angeles, occupying a private compartment, singing train songs and working on new tunes the whole way. Together they wrote “Hickory Wind” and talked about their mixed feelings about returning to California. “We had family and locations that were very familiar,” Bob says, “and now we were going back to the City of Angels that was killing all the angels. I think deep down inside we both had this resentment for that Hollywood thing. Sucks people in and spits them out. He and I were aware of that, so we were both getting very cynical at our young age.”

Gram was coming back not only to Los Angeles but to his girlfriend. Nancy, feeling neglected, dramatized her upset with a range of attention-getting techniques. Tensions increased when Nancy became pregnant, in March. None of Gram’s friends believed he’d intended to become a father.

It’s an old story in rock that band members have little patience for girlfriends. Notwithstanding this tradition and the shortage of slack that Nancy would have got from Gram’s musician friends in any case, the tensions between Gram and Nancy during her pregnancy were real.

“We were having a meeting at my house with a couple of big-time guys, record executives,” Bob Buchanan says, “and Nancy took my car. Suddenly Nancy’s had an accident. She went four blocks and totaled it. ‘Come and save me!’ So the meeting’s over, and we had to go save Nancy. It was outrageous. I’m sure she didn’t try to do it on purpose, but she’d get herself in predicaments. Running up a bill here, or forgetting to do this, and Gram was busy being Gram. She had depth and stubbornness, so they were like two roosters in the pen.”

Nancy was accustomed to a certain level of drama. “She thrived on craziness,” Bob says. “Anybody that was hanging around with Steve McQueen and David Crosby and Gram Parsons had to be nuts. Nancy was outrageous on her own and she liked the excitement. She had an agenda: to be the famous one next to the famous one. She wanted to be Gram’s wife instead of girlfriend. She went to the point of trying to get him to come home and not be out running around all over the place being a musician. But she couldn’t get her way, and she was as stubborn as they come. Without meaning to, she could be quite a destructive force.”

Gram made no apparent effort to soothe Nancy or prepare for fatherhood. “Say Gram was trying to help somebody who OD’d,” Bob says. “Nancy would rather preach to the person who OD’d: ‘It’s not good to use needles, it’s bad for you,’ with the guy dying in front of her. She didn’t know how to deal. She’d call the ambulance or the police, and those were the wrong people to call. You don’t want the guy to die, but you don’t want everyone to go to jail, either.

“At this time Gram was not using needles, but I certainly was, and Fred Neil and Tim Hardin, a lot of people. All I saw Gram do was smoke his pot and once in a while he’d snort a little heroin. Gram liked his pot, but he was nowhere into needles.”

GRAM CONTINUED TO SEARCH for and hang out in the roughest country bars he could find, seeking the essence of the music. Like any serious mystic, he was convinced of the link between the magic and the setting. He became a regular at the Aces. “The Aces was rough,” David Barry says. “Everybody had a gun in their car. And a posse of L.A. sheriffs [sat] in the parking lot waiting for the inevitable brawl—those guys would shoot anyone.

“The toughness was part of the beauty of it. I loved it. Gram did, too. The City of Industry”—where the Aces was located—“was one of the worst places on the planet. The Aces club was the toughest place around, because not only Anglo rednecks but Mexican rednecks went there. The Mexican rednecks had plenty to fight about amongst themselves, but you put them together with the Anglo rednecks and you had a nice mix goin’ on.

“Of course the Aces had a country band. Country musicians tended to be crazy in a way that rock musicians weren’t, because the country drug was amphetamines and the country guys were always wired. To get a fight going was easy, and that was the scene. The Aces was the ground zero of country music in L.A. County.

“Gram described sitting outside that club. He’d been playing with David Crosby at an open mike. He described this strange hostile beauty and the sun coming up orange over the San Bernardino Mountains behind the oil derricks. He was so lyrical about it. That was his metaphor for his love of country music. He knew the shit-kicker mentality that produced the mix that all this music came out of. Gram knew the mentality informed the playing. That was not true of a lot of the guys who played country rock. Gram did not want a rock-diluted version of country music. He was into the real thing.”

To record the album that came to be called Safe at Home, Gram and John Nuese set out to put together a band that would manifest that reality. While in Winter Haven, Gram tried to recruit local bass heavy Gerald Chambers. Chambers didn’t want to move to Los Angeles. Gram ran into drummer Jon Corneal, a man who knew country music. “I was down for my yearly visit home to see the orange blossoms,” Corneal says. “I had already moved to Nashville in July 1964. In 1965, Gram had a folk group [the Shilos] and he made fun of me for playing country. When I ran into him in 1967 he said, ‘Man, I’ve got some music I want to play you, some stuff I’ve discovered.’ And he had a reel-to-reel tape full of George Jones, Merle Haggard, Buck Owens, and Loretta Lynn, like he had discovered them. I had come off some Grand Ole Opry–style jobs. I had worked for the Wilburn Brothers for a year, Roy Drusky, Kitty Wells, and Connie Smith. I was leaving Connie Smith when I ran into Gram. I’d come off the road with the Wilburn Brothers.” Corneal was willing to relocate. He was in.

They hunted down steel-guitar player Jay Dee Maness. “Jay Dee had a DA haircut,” John Nuese says, meaning a duck’s ass, a high-topped, greased-back 1950s shit-kicker roll of hair ending at the back of the neck with a feathered, tapered flip like the hind end of a duck—“pointed shoes, and a skinny tie. He was leery of us hippie types, skeptical at first. I didn’t know him well, but what a player! He developed his own style and was one of the best steel players of all time. So we got him and Earl Ball, a piano player. Jon Corneal played drums and Chris Ethridge played bass. He’s from Meridian, Mississippi, and a great R&B bass player.”

“I started playing the pedal steel when I was eleven,” Jay Dee Maness says, “and was playing bars by age fifteen. My dad said, ‘If you always play that instrument you won’t ever go hungry. You’ll always be able to work.’ He was right.”

Jay Dee leaned on Gram and John to bring in Earl Ball on piano. Gram was reluctant to have any piano on the record; he wasn’t intending to play himself. He wanted a purer Bakersfield sound: rhythm and lead guitar plus steel, bass, and drums. But Jay Dee nagged until Gram gave in. Earl Ball remembers, “Jay Dee Maness came to me one night and said, ‘There’s this bunch of hippie guys and they’re trying to do country music downtown. They’ve got me hired to play steel guitar, and this guy plays the piano, but says he’d rather have a real country-music piano player if I knew one. I told him about you, so you come on down and do the session.’ That’s how I got connected with Gram.”

Earl Ball was the real thing. He first played on Jimmy Swan’s radio show in Hattiesburg, Mississippi, hitchhiking into town from the family farm for the show and hitchhiking back afterward. He played Ray Price and Hank Williams songs and made ends meet working door-to-door as a Fuller Brush salesman. Earl hooked up with a Johnny Cash soundalike, Danny Ray. Their travels took them to Los Angeles, where Earl became house pianist at Olie’s Bar, which later became Okieville. There Ball came to love the sound of Bakersfield honky-tonker Wynn Stewart and added rockabilly to his country playing. After a year at Olie’s, Earl became the house pianist at the Aces. “The ISB was the first people I ever heard of with that look,” Earl Ball says, meaning hippies, “that wanted to play country music.”

Earl and Jay Dee, whose standards were rigorous and unyielding, regarded Gram as something of an alien. “I thought, ‘This is a young guy and he sings pretty good,’” Jay Dee says. “He was never a great singer. But he wanted to be and he worked at it. What I call a great singer is George Jones or George Strait. Gram was always kind of in the middle, which became the trademark country-rock thing. None of them were great singers—they sang the way they felt it. Like the Rolling Stones. Those guys do great but they’re not great singers.”

Jay Dee and Earl’s reactions suggest the musical and cultural gulf that Gram was attempting to bridge. Gram wasn’t the only one hanging out in scenes he found seductive yet foreign and unsettling. “I went to his house one time when they lived on Sweetzer in Hollywood,” Jay Dee says. “It was quite an eye-opener. That was my first introduction to what we called hippies. It was like going into a garden. There were plants and strange things hanging on the walls. I hate to use the word hippie, but it wasn’t like going to a normal person’s home where you sit down to a meal. It was like going to a museum or thrift store. I thought, ‘They actually live like this?’”

Earl believes that it was drugs, rather than music, that eventually led the country and rock musicians to understand each other. “The country players took up marijuana,” he says, “and the rockers started in with speed.” In 1967 that magical rapprochement was still a couple of years off.

John and Gram rehearsed at Suzi Jane Hokom’s Laurel Canyon house. It turned out that she, with the blessing of her boyfriend, Lee Hazlewood, was going to produce the ISB sessions. John taught Gram flattop guitar parts with an emphasis on the chugging country backbeat. The band went into Studio B of Western Sound Studios in Hollywood in July 1967. Two songs were cut, both Gram originals: “Blue Eyes,” a shockingly accurate attempt at a Buck Owens domestic-bliss romance ditty (with a perfectly executed Buck Owens kindergarten chorus), and “Luxury Liner.” LHI Records released the two songs as a single.

The culture clash between rock and country was manifest in the studio. “We didn’t record the way I usually do,” Earl Ball says, “because I tried to have my band be a little more polished. I was older, only twenty-seven, but still older. I thought it was kind of rough, but maybe that’s the way the kids needed to hear it, a bit more rock and roll, in a looser form than Nashville.”

It was Gram’s first exposure to the way of country studio musicians as exemplified by Jay Dee Maness. “Jay Dee had a little problem with the whole long-haired hippie thing,” Bob Buchanan says. “He thought it was weird. Everybody on break going out and smoking a joint. Jay Dee would stay inside and drink coffee….

“He was used to working with great names; Jay Dee was a classic for-hire studio musician. Those guys hung around Nashville at these open-all-night restaurants sipping coffee and taking speed, waiting for somebody to come in and say, ‘Hey, so-and-so had to go home, you want to fill in?’ These guys were incredible players, and there would be anywhere from three to thirteen of them waiting all night to do a session. That was their livelihood, and it was good money. Once in a while they’d go on the road with a band, but they would rather be home with their family.

“Jay Dee was far and away a great steel-guitar player. He came to work like punching a clock. But he was not in his element. He’d say, ‘What do you want?’ Gram would say, ‘Do something you feel,’ and Jay Dee had a hard time with that. He wasn’t used to doing what he felt. All he was supposed to do was play the steel.”

If Jay Dee Maness stood for working-class professionalism, Earl Ball represented the universe of Southern California roadhouse honky-tonk speed. “I was a beer man,” Earl says. “Beer and uppers. Because I did those long jam sessions, I’d try for balance. I’d drink a good whiskey with those uppers, a bar whiskey, Kessler’s bar whiskey, and those round speed tablets you could get back then with the smooth edges…. That was the hillbilly music culture. The rock guys or hippies were doing more pot and a little LSD. But I went to this doctor one time, told him I wanted to do some LSD, what’d he think, and he said it would eat my brain up, so I said, ‘Well, okay, I won’t do that.’”

For a band with such diverse views on drugs, the ISB managed to produce a cohesive sound. With no thanks to Suzi Jane Hokom, whom the band considered a meddling amateur. “She was bossy in the studio and insisted on a piecemeal recording,” John Nuese says. “We were at loggerheads because she didn’t understand the procedure we used, which was to get everyone together and get a sound. Then you do the song.”

“We had some real difficult times making that album,” Suzi Jane Hokom said. “We had to do it in about two weeks because Lee [Hazlewood] didn’t want to spend a lot of money. I had big problems with John Nuese. He hated me. There was nothing I could do to make him like or accept me. It was a battle with him every day.”

Though she and John Nuese disagree on every aspect of the sessions, one thing is clear: They battled constantly. John’s complaints about Suzi’s preference for recording piecemeal referred to doing a lot of overdubs. John had problems playing live and preferred to overdub his parts. Nevertheless he was reluctant to relinquish control. Gram was, too, even as he held back from firmly taking charge.

“Suzi Jane Hokom more or less had charge of things,” Jay Dee Maness says, “but musically we did what we wanted. We didn’t have a direction. We just played. Gram would go, ‘Here’s a song I want to do,’ and we’d look at each other and go, ‘Okay, you play the chorus and maybe you play the…’ Or we’d all start playing and it would fall in place. We’d develop it on the spot.” Bob Buchanan recalls, “It was the Gram Parsons Show. Suzi Jane Hokom had no idea what sound anybody was after. The sessions were like a toy. Lee Hazlewood’s a producer and he wanted to give his girlfriend a gift, a band to play with. But we didn’t know what sound, either. John Nuese and the band knew it was Gram’s show. They went in and played what he wanted.”

In addition to the stress of working with a producer who could neither guide the band nor help them find what they thought they wanted, tensions were emerging between Gram and Jon Corneal.

Jon had hoped to record his own originals for the album. He told the others he was a better singer and guitar player than Gram. He complained that Gram had promised him a chance to cut his own songs and felt he’d been lured to California by false promises. Jon had been in L.A. less than two weeks when Gram told John Nuese, “I have some reservations about having invited Corneal.” Moreover, Corneal proved too much of a shit kicker for the band’s social vibe. Or perhaps his shit-kicker behavior lacked the cool veneer that came naturally to shit kickers like Earl Ball and Jay Dee Maness. Corneal felt out of his depth in L.A. and took offense easily. Not having a girlfriend, Corneal was reduced to tagging along after Gram.

Gram brought the band to a few high-end Hollywood parties in the hills. At first people were amused by Corneal, who wore overalls and “fart kicker” boots and talked, as one bandmate put it, “like a stone-kicking farm boy.” When the sophisticates realized it wasn’t an act, the amusement soured. “You knew he wasn’t going to make it for long,” Bob Buchanan says.

Alone among the band, Jon was impressed by Suzi Jane Hokom. He insists that she played the ISB’s record for George Harrison when the Beatles were looking for artists for their Apple label. Suzi told Jon that Harrison wanted her to produce an ISB record for Apple, but that Lee Hazlewood wouldn’t allow it.

The band took a break after the release of the single. “Money was not a problem to Gram,” Jon Corneal says in Desperados. “He had plenty of it. But I had to work for a living. We needed to be gigging, but we weren’t. Gram and I used to go out and play places. We actually could have performed, but John didn’t want to, so Gram and I would go sit in at the Palomino. It was kind of a strange situation. But I knew I could go back to Nashville and get work.” According to Einarson, Corneal went back to Nashville and returned when the recording sessions picked back up.

Sessions resumed in November with little structure. “I’d walk in,” Bob Buchanan remembers, “and Gram would say, ‘We’re gonna do “Strong Boy.”’ And we’d run through it once or twice by memory. ‘Bob, why don’t you try singing an octave below me or a harmony?’” When Buchanan and others sang harmony with Gram, Suzi Jane tweaked the volume in their headphones, making it sound as if the others were as loud in the mix as Gram. In fact, the harmonizers were reduced to background vocalists without their knowledge. “So it wasn’t a band,” Bob says. “It was a Gram album with the band behind him. They called it the International Submarine Band, but Gram picked the songs and the harmonies. It was all Gram. Even Suzi Jane was obligated to get along with him. John would say, ‘Let’s do this part in the break,’ and if it sounded good to Gram, fine. If he didn’t like it, he would tell you and it wouldn’t happen. There was no equality in the band. Gram was the show.”

Glen Campbell came by to play guitar and add tenor vocals. Poised on the edge of stardom himself, Campbell at the time was a highly regarded L.A. session musician with credits on Brian Wilson’s Pet Sounds, among others. The session men, like Earl Ball, got along fine with Gram. They were not dependent on him for their home or their food.

Gram pursued a different dynamic with everyone else. He wasn’t afraid to bully the band. When John Nuese and Gram argued, John usually backed down. In the words of one of the session players, John Nuese “didn’t want to get in the way of the Gram Parsons machine. If Gram had an idea and Corneal didn’t like it, Gram would say, ‘Leave the session. I’ll get another drummer.’ Nuese and Corneal were upset. They both thought it was going to be an even band. There was not a lot of happiness. Of course Gram would never do that to Glen Campbell. Gram was in awe of the people who were good. If you earned Gram’s respect, you had it.”

The dissatisfaction spilled over at the band house. When Jon Corneal couldn’t take it anymore, he said those classic rock-and-roll band-breakup words: “Who does he think he is?” The inevitable realization followed: “I haven’t any money. I don’t have any work here. I’m broke. I’m going home.”

The overdubs were recorded by Hokom and Gram and whoever was necessary, day by day. “We were there several weeks for the first stint,” Bob Buchanan says. “Then we realized there were some weak points. We overdubbed some of the rhythm guitars and harmonies. By that time I had distanced myself from Gram. I went in, but I was in bad shape with my drug addiction. I wasn’t able to do the rhythm guitar parts. They had to get another guy.”

Gram showed a new level of assertiveness, a drive and a sense of ownership over the music. Musically and emotionally, Gram was a collaborator only to a degree. After years of wanting the spotlight, he did not waste his opportunity. Patterns were established that would hold true in all his recording sessions: a distaste for structuring his material before going into the studio; a preference for playing live with the tape machine running; not much interest in listening to a producer; ruthlessness about finding the best player for the part, regardless of whose feelings might get hurt; and a sense that everyone was laboring in the service of his vision.

In fairness, Gram drove himself to a standard that made it reasonable for him to be ruthless with others. At first listen, an outstanding aspect of Safe at Home is the skill with which the band apes then-current and traditional honky-tonk forms. To seek to capture those forms was a revolutionary, not evolutionary, step in 1967. There were no longhair rockers exploring these sounds with Gram’s accuracy and attention to detail or his fealty to the cultural mythology underlying the music. The album is pure City of Industry honky-tonk, executed with loving gusto and hell-raising sincerity, even on the joke songs.

“There are those that say the best thing Gram ever did was the International Submarine Band record,” John Nuese says. “The singing is great. It’s better than his later singing. He wasn’t drinking, he wasn’t taking hard drugs, he was concentrating. And that’s one of the things that made that album hold its position over the past thirty-seven years.”

Also evident on Safe at Home is Gram’s quirky, bemused genius for picking cover songs and his music-archeologist’s attention to aesthetic detail in performing them. He shows an astonishing grasp of the idioms in which he wrote originals as well. With his connoisseur’s ear, Gram demonstrated that he technically, emotionally, and musically understood the tiniest difference between highly specific country styles and traditions.

At the same time, he proved to have a tin ear regarding some material: His covers of Johnny Cash’s “Folsom Prison Blues”—which medleys into Arthur Crudup’s “That’s All Right Mama” (an early hit for Elvis)—and “I Still Miss Someone” are throwaways. They show little insight into what makes Cash’s minimalist delivery so potent. Alone on Safe at Home, these three covers lack soul. Jon Corneal overplays in the shuffle version of “Folsom/All Right.” The band is reaching, trying to infuse energy into arrangements that work against them. A stronger producer, or maybe any producer at all, might have imposed some needed discipline.

Another cover, Merle Haggard’s “I Must Be Somebody Else You’ve Known,” shows much more exuberance than Merle’s world-weary delivery. The song slows in the middle and never recovers its pace—perhaps two different takes were spliced together. There’s a palpable joy in Gram’s singing and great, understated tempo comping in a Floyd Cramer style from Earl Ball. Gram’s love of wordplay and puns (evident from his early song “Sum Up Broke” to the double meaning of Safe at Home) is clear in how much he enjoys singing the title line.

Porter Wagoner’s “A Satisfied Mind” had been covered by the Byrds on 1965’s Turn! Turn! Turn! The Byrds performed it as the classic folkie’s lament about the perils of chasing after money (like that other folkie fallback, “The Ballad of Richard Cory”). Wagoner’s own version is right out of the hymnal. It’s lugubrious and echoes the slow-motion sincerity of the Louvin Brothers. Porter sings with such churchy sadness, you can almost believe the message: Be grateful you’re poor. Gram’s vocals are never equal to the song; his focus on singing with feeling keeps him from feeling whatever emotions he’s seeking. It’s hard to imagine that “A Satisfied Mind” was any fun for either the Byrds or Gram. The song is such a lesson. It’s as if Gram was determined to demonstrate his broad grasp of the canon: a couple Johnny Cash songs, a Merle, and a Porter Wagoner. Given that no one on earth can sing as slowly as Porter Wagoner, covering “Mind” in Porter’s style is a fool’s errand.

Even so, Earl Ball and Jay Dee Maness shine. The pedal steel is a virtuoso’s instrument—fretless, scaleless, and requiring two hands and feet. On “A Satisfied Mind” Jay Dee takes the steel through all its roles: lead guitar seizing the spotlight for a solo; string section providing a smooth road down which the other instruments travel; a horn section adding rhythmic punch; and that ineffable Greek chorus steel-guitar commentary, wherein the great players somehow manage to be within and without the song—moving it along and telling us about its themes at the same time.

“Cowboy” Jack Clement’s “Miller’s Cave” demonstrates Gram’s cunning at choosing unlikely covers and his glee in singing them. “Miller’s Cave” is that staple of the country charts, the story song. Some are historical narratives, like Johnny Horton’s “Battle of New Orleans” and “Sink the Bismarck” Jimmy Dean did Homeric epics like “Big Bad John” Ray Stevens made his name with the low comedy of “Ahab the Arab.”

“Miller’s Cave,” first brought to the charts by Hank Snow, historically aligns with Porter Wagoner’s “Cold Hard Facts of Life.” Both feature O. Henry or de Maupassant endings: an unexpected twist reveals the song to be told in flashback by a narrator who’s in big trouble. Gram altered the first line in the song to change its setting to “Waycross, Georgia.” He understood the original sufficiently to bring in a big, booming Mitch Miller–style multitracked male chorus for the final verse. Of all his faithful renditions of lower-brain-function country, this is the most deadpan and fun. Gram strives for emotion on the more canonical covers. This joke song seems his most sincere.

“Luxury Liner” demonstrates, in the arrangement as well as the lyrics, the future of Gram’s songwriting, the power he would find in his own pain. Part of the shock of the music of singer-songwriters George Jones, Lefty Frizzell, Wynn Stewart, and other honky-tonkers lies in their straightforward descriptions of their fucked-up lives, inability to love, life-altering romantic mistakes, and distanced self-perception. Their view of self is always through a prism of anguish. Country pain is expressed often without metaphor, simply and plainly. At first the expression seems crude and comical, but once the force of the music hits, it’s the bottomless emotional torment, and the singers’ naked confession thereof, that make raw country so moving.

“Strong Boy” is one of the last times Gram would tout his strength, rather than his weakness. Again relying on the shuffle beat, Gram tells off someone competing for his woman’s affections. It’s a brag song and seems incongruous, but he sings it with gusto. Earl Ball takes a cheerful, galumphing solo until Jay Dee Maness comes in with a real showpiece solo.

Safe at Home ends with Gram’s most straightforward and mournful song. “Do You Know How It Feels to Be Lonesome?” addresses the alienation that plagued Gram and describes depression with clinical precision. Andrew Solomon, author of The Noonday Demon, describes the salient aspect of depression as the constant illusion that one is alone and disconnected. The band treats the lyrics as typical honky-tonk: Earl Ball loses himself in tinkling Ray Price solos, and Jay Dee stretches the end of each lyric line with lingering, sorrowful wails. Though a chorus of almost-Nashville girl singers provides a soft bed of “ooooohhhs” under Earl Ball, the attempted sweetening only emphasizes the isolation of the singer. From this song onward, Gram’s best lyrics would place him on the outside looking in at the world and at himself.

Do you know how it feels to be lonesome?

When there’s just no one left who really cares

(Words and music by Gram Parsons)

Peter Doggett wrote in his exceptional history Are You Ready for the Country: Elvis, Dylan, Parsons and the Roots of Country Rock: “Ironically, the same isolation from the times which marked Safe at Home as a historical dead end is its greatest artistic strength.” Yet time has proven that Safe at Home was not a historical dead end: The ISB’s enthusiasms were simply alien to the rock-and-roll culture of the moment. Just as hippies walked into country bars with a wholly reasonable fear of being unwelcome (“And all they seem to do is stare”), country music was equally unloved and misunderstood by the larger rock audience. Gram and John Nuese loved the pain, the sincerity, the raucous ecstasy, and the deceptive simplicity of country music. They burrowed into its forms with an acolyte’s devotion. Corneal, Ball, Maness, and bassist Chris Ethridge didn’t need to learn. They were living it.

The most argued and least interesting question of Gram’s legacy is whether he invented country rock. Anyone immersed in the history of American popular music understands that almost nobody invents anything. (Miles Davis’ psychedelic period might well be the exception that proves the rule. Ditto Sun Ra and Mr. Cecil Taylor.) Sounds emerge as synthesis, in evolutionary steps; musical styles bleed into one another; musicians at different ends of the continent have similar ideas at similar times.

Almost four decades removed from the moment, though, it’s hard to remember how radical a breaking down of walls, a liberating of ghettos, Safe at Home proved to be. In 1967 there was nothing like it being recorded in rock and roll. The combination of rocker exuberance, roadhouse scholarship, and Nashville session tradition generated a new form.

In 1972, Gram told Chuck Cassell, an A&R man at A&M records, that Safe at Home “is probably the best country album that I’ve done. Because it had a lot of quick shuffle, brilliant-sounding country. Once in a while in the Burritos I’d run into some freak who had nine copies of it. Nobody else had ever heard of it. I had, like, four songs that I’d written on it that were good. I was real young and I got carried away. It was all recorded in a week. Mixed in one day.”

The album was not recorded in a week or mixed in a day. And in his conversation with Cassell, Gram sounds high as a cooter. Their interview occurred during a phase when Gram was most full of bullshit when talking to journalists or A&R types. His clear affection for Safe at Home still comes through.

Recording finished in early December of 1967. The wrap-up of the album coincided with the birth of Gram and Nancy’s daughter, Polly.

Having completed his first album and fathered a child, Gram abandoned his band and showed little interest in parenting. Shortly after their album was in the can, Gram left the ISB and charmed his way into a new band that offered greater fame and much more poisonous group dynamics.