FIFTEEN

THE GILDED PALACE OF SIN

GRAM TOOK THE BAND TO NUDIE’S TO GET CUSTOM SEQUINED SUITS FOR THE album cover shoot. Knowingly or not, A&M footed the bill. Chris Ethridge’s suit was tailored in an Edwardian cut with a below-pocket-length, double-vented white jacket. It had high lapels and was covered in ornate roses: Red blossoms climbed up each leg; red roses on green stems decorated the sleeves, chest, and lapels; yellow bouquets provided accents. The back featured a huge three-stemmed red rose and two yellow free-floating blossoms above.

Sneaky Pete got a black velvet pullover shirt with a gold pterodactyl in full flight on the front and twin Tyrannosaurus Rexes rampant on the back. The shirt matched his plain, full-cut black velvet pants. “I designed my own,” Pete says. “I was a motion picture special-effects guy, so I figured dinosaurs, wow, that’d be great.”

Chris Hillman’s screaming neon-blue suit had a business cut, with peacocks of gold and green on the chest and sleeves. The back was a golden sunburst. The pants had red sequin peacock feathers and vines unfurling up his legs.

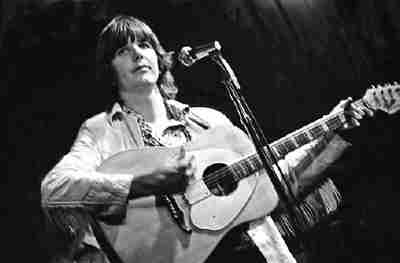

The Gilded Palace of Sin photo shoot: Chris Ethridge, unidentified, Gram Parsons, unidentified, Sneaky Pete Kleinow, Chris Hillman. (© Barry Feinstein, www.barryfeinsteinphotography.com)

Gram’s suit, a garment of legend, hangs in the Country Music Hall of Fame. It reflects his passions and contradictions, Gram’s brazen sense of humor and his insistence that his most outrageous statements be grounded in country traditions. The belled pants are jean-cut and hang low, with scarlet flames reaching up the legs and poppies on the front pockets. Poppies cover the back pockets, too. A naked woman, rendered as an old-school sailor’s tattoo, adorns each lapel of the belt-length, silk motorcycle jacket; red poppies embellish the shoulders. Growing up the chest are carefully articulated, deep-green marijuana leaves. On the sleeves are embroidered Seconals, Tuinals, and a sugar cube representing LSD. In blazing contradiction to the women and the drugs, the back of Gram’s jacket is covered, top to bottom, by a flaming red cross surrounded by radiating shafts of blue and gold light.

“The first couple of times I played the Palomino I nearly got killed,” Gram said. “There I was in my satin bell-bottoms, and the people couldn’t believe it. I got up onstage and sang, and when I got off a guy said to me, ‘I want you to meet my three brothers. We were gonna kick your ass, but you can sing real good, so we’ll buy you a beer instead.’ Thank God I got up on that stage.”

“They thought he was out of his mind,” Miss Mercy says. “They were like these conservative rednecks, right? And they’re goin’, ‘What the hell?’ Big cross…he had the big Nudie cross on the back of his suit. They thought it was anti-religious. It was absolutely hilarious. People didn’t get it.”

For the album cover shoot the band posed in Pear Blossom, California, in the desert east of L.A. They stood in front of a tiny shack meant to represent a whorehouse, the Gilded Palace of Sin of the title. Two models lounge against the shack and, on the back cover, in the arms of Gram. Gram and Ethridge wear their suits with aplomb. Hillman’s suit appears to be wearing him, and Sneaky Pete might as well be wearing pajamas. The band looks uninterested and high, save Sneaky Pete. He looks intense and strange, like a pedal-steel player.

The Gilded Palace recording sessions ended in January. The Burritos were unveiled in all their glory at a promo show at the Whisky a Go Go, the center of the late-sixties Sunset Strip. A small club with a high ceiling, the Whisky was dominated by a postage-stamp stage seven feet off the floor. Tables and a dance floor curved around the front of the stage, and a shallow standing-room balcony wrapped around above. The proximity of the audience to the stage, and the crush of the crowd at a well-attended show, turned the Whisky into a cauldron of sweat and energy.

The opening act, which had been booked by Warner Bros., was Van Morrison—then and now a notoriously difficult guy. “The place was packed,” Vosse says. “Van was drunk—no big surprise—and he was not about to stop. Long past where the first set was supposed to end, Van kept going and going. The Burritos were getting agitated because they wanted to get onstage. The people that we had gotten to come see them were like, ‘Jesus Christ, I’ve got to go.’ I remember yelling at people from Warner, saying, ‘Get this fucking guy off the stage!’ They said, ‘You don’t understand. There’s nothing we can do!’”

When Morrison finally stopped, the Burritos went on an hour late and nervous. “I cannot tell you for the world whether they were good or not,” Vosse says. “It was a nice evening and it accomplished what it was supposed to accomplish.”

Vosse adds that the band’s club performances were rarely stellar. “Usually they were underrehearsed. All it took was for one or two of them to be on coke and not on the same page.

“It was never horrible, because Sneaky Pete could save anything. You’d turn to Pete during a bridge and let him do a solo and take the lead and songs could come back together again. Gram could sing when he was fucked-up, that was the other thing.”

“I cannot recall one performance where I was not embarrassed to tears,” Sneaky Pete says. In his recounting of that evening at the Whisky, Jerry Moss and Herb Alpert were sitting in the audience, waiting to see A&M’s new band. “Gram was so stoned he couldn’t play the piano. Chris Hillman, of course, was right up there plugging, but Chris Ethridge had smoked a little too much of something.” Ethridge grew progressively more disoriented until he passed out. A roadie scooped up his bass and stepped in to replace him. “The suits got up from their table in midconcert and walked out,” Pete says. “We thought we were finished. It was typical.”

“On Monday nights the Troubadour had a Hoot Night, which was an open-mike night,” guitarist Bernie Leadon says. “You had to sign up and be approved by the guy who ran it. The Burritos showed up wearing their Nudie suits. There was quite a buzz about them. I sat there and couldn’t believe what I was seeing because they were so bad. It was atrocious. It was as if they had never met. Nobody had electronic tuners, and they were out of tune. They didn’t stop and start at the same time. They didn’t sing in tune. I couldn’t believe it. I went, Wow, there’s something here, but I can’t make it out.”

A thorough listen to most live bootleg tapes from 1969—before Bernie Leadon joined the band—reveals the Burritos to be unbelievably sloppy, even by the lax standards of live shows at that time. They could occasionally nail the moment, as their blistering set at 1969’s Seattle Pop Festival demonstrates. The Burritos’ consistent inconsistency makes it clear how seldom they rehearsed. Bakersfield music isn’t hard to play. Buck Owens turned it into an art form by performing his simple compositions with rigorous Zen discipline. There’s no question the Burritos were skilled musicians—except for drummer Michael Clarke. The Byrds’ original drummer joined the Burritos officially. He could not keep time. His beats are ragged. Sneaky Pete zings his deranged Sun Ra–like steel lines across every minute of every song. The band was too disorganized for Sneaky to play carefully placed accents. The absence of lead guitar meant the soloing fell to him. Gram sounds more high than anything else, disconnected from the songs and singing with all his might. It’s difficult for any band to pull off live shows that reflect their true abilities. The Burritos’ laziness makes their performances painful.

The addition of Michael Clarke, who’d been playing with Dillard & Clark, didn’t help the band. Gram biographer Rick Cusick refers to Clarke as the King of Common Time, meaning that all Clarke could play was 4/4. “I know Jon Corneal played on tracks on the album. But he looked like a schlump. And the Burritos wasn’t about that,” a member of the Burritos organization says. “The Burritos had to be pretty. Corneal didn’t fit. They didn’t even put him on the cover. They needed someone pretty. Michael Clarke—for all of his bad points, chicks dug Michael Clarke.”

HILLMAN AND GRAM conceived a band tour by train, like the old-school country stars. Lacking a proper manager—Larry Spector had been fired—they hired Keith Richards’ factotum Phil Kaufman as their road manager. Michael Vosse came along for the hang. “I didn’t work for the Burritos,” Vosse says. “I worked for A&M. It was a promotional tour. It was easy to go. It was cheap. A&M was paying for it.”

The day after the going-away party that launched the tour, Pamela Des Barres wrote in her diary, “Gram was practically stuffing [cocaine] up people’s noses on the train last night—big globs of it. I had the feeling at the station that Gram wanted to be wild and free. Brandon and I are driving up tomorrow to see Nancy.” They wanted to console her; she was still suffering over Gram’s wedding ruse.

The train tour was bound for Chicago, Detroit, Boston, New York, and Philadelphia. Reliving Gram’s trips from Waycross to Winter Haven, the band had its own car and everyone had his own compartment. In Phil Kaufman’s book Road Mangler, Kaufman reports that he insisted all the musicians give him their drugs. He argued it was safer to have all the dope in one place, and for each person to come ask him for their drugs, than to have six separate stashes scattered about the train. “It was debauchery personified,” Kaufman writes.

Michael Vosse did not like Kaufman. He thought Kaufman had no idea how to manage a tour. Cocaine was Kaufman’s drug of choice, he says, “because the Burritos would give him money to buy drugs. Still, the baseline was marijuana. People were happy getting high on marijuana and it was easy to get. Everyone was always smoking a joint except for Sneaky Pete. I never even saw him drink.”

“Things were always going wrong with the Burritos,” Hillman said. “We toured before the album was out, so audiences didn’t know what to expect.” The band arrived in Chicago to discover they had no promotional appearances booked. Michael Vosse knew the Chicago journalist Studs Terkel (author of Working and Hard Times) and asked if the band could appear on Terkel’s popular radio show. Terkel, unsurprisingly, had never heard of them. He listened to their record and agreed. “Gram and Hillman were good,” Vosse remembers. “Ethridge and Sneaky were pretty quiet.”

The band stayed in a small hotel with an expensive, highly regarded restaurant on its ground floor. “The band found out that they liked the lemon soufflé, so late at night they would order dozens,” Vosse says. “They would hoard the soufflés and eat them. It was this panic situation with the soufflés, like somebody might wake up at three A.M. and have to have one.”

Gram was drinking heavily and doing a lot cocaine. “I never saw Gram do that shit out in the open,” says a Burritos source. “One of the reasons was Michael Clarke was an addict. And if you had powder, as he called it, he would be all over you. Gram didn’t want Michael to know he had powder. He’d sneak off to another room and maybe take Hillman with him. Michael would come around and say, ‘Where’s Chris?’ And he would nose his way into the bathroom. If you had an ounce, Michael would do an ounce and a half. That was his m.o.”

Sneaky Pete did no drugs. He seldom socialized with the band after shows. He liked to go back to the hotel and call his children. Sneaky was the one Burrito with a real job—animation. “Woe unto anyone who would be mean to Pete,” Vosse says. “The one person everybody thought was most important for the sound of the band was Pete. He was so fucking good and awesomely hardworking. If the guys were having a bad night, he was not having a bad night. He didn’t have bad nights. He had nights where he would get irritated because things weren’t going well. He wasn’t a junkie or a drinker. So when they would go to the hotel to do coke and go over the show, he was nowhere to be seen.”

In Boston the Burritos shared the bill with the Byrds. The prospect of being outplayed caused the band to be more sober—or at least less fucked-up—for that show than for any other on the tour. The Burritos’ set included “Close up the Honky-Tonks” and “Sing Me Back Home.”

After the show, Gram took the band to visit Jet Thomas. “He had a little apartment on Harvard Yard,” Vosse remembers. “It was so wonderful. It was snowing and we all got invited. He had a collar, which he had unhooked. I think he had just done vespers or some bullshit. He had this dream apartment with plenty of books and nice leather chairs and pipes. He was so hospitable and polite. Scholarly people smoked pot. He had this fishbowl full of pot and Ethridge did nothing but look at it. Ethridge was just, ‘Ahhh.’ He had this big smile and his eyes were real big and he didn’t know what to do about it and he said, ‘Michael? Do you think that that’s pot? Do you think he’ll give us some?’ It was as if Chris had walked into the enchanted forest. He’d never seen anything like that in his life, plus the guy was in a collar and we were at Harvard. After we left we talked about it for hours. It was like [imitates Chris], ‘We’re in Boston, Massachusetts…we’re at Harvard University, that person is a priest [sic], and there is a big bowl of marijuana on his coffee table?’ Chris thought that this meant the world was going to be fine.”

The first show in New York City was to be at Steve Paul’s Scene, a cramped, happening basement in midtown Manhattan. A snowstorm canceled flights from Boston to New York. Kaufman failed to organize transportation and each band member made his separate way. Anarchy ensued. One Burrito (the source for this story wouldn’t reveal which one) rented a car with a friend, dropped acid on the road, got hopelessly lost, and showed up in New York a day late. As a result, the band—A&M’s big new signing, featuring two ex-Byrds—did the unthinkable: They missed the gig.

A&M was infuriated. They regarded the New York Scene performance as the whole point of the tour. The Burritos’ lack of professionalism made A&M look ridiculous. The label worked to get the New York rock press to the show. There was no show for them to see. A&M blamed Vosse; Vosse blamed Kaufman. The Burrito whose absence caused the problem was “all coked up,” Vosse remembers, “and angry that anyone made an issue out of it.”

To make matters worse in the eyes of A&M, Vosse had shifted the band to a more expensive hotel only hours before the missed gig. A&M had been readying costly support for the Burritos. Jerry Moss was trying to get David Geffen (creator of Asylum and Geffen Records and later co-owner of the film studio Dreamworks SKG) and his partner to manage the band. Geffen had signed Crosby, Stills and Nash and so was reluctant to help the Burritos. Between the missed showcase and the indulgent hotel, A&M lost patience with the band. They wrote the Burritos off as a bad investment.

The band did manage to make their second scheduled appearance at the Scene. Billboard writer Fred Kirby reviewed the band’s one show in New York: “Country-style music landed at Steve Paul’s Scene on Tuesday in the person of the Flying Burrito Brothers [who] brought the act in splendidly….[The band], whose first A&M album is due early this month, would seem to have a bright future with country music becoming one of the day’s in sounds.”

In Philadelphia Gram bought everyone turbans to wear onstage. They were both ridiculous and an obscure homage to the crazily dressed soul singers of the past. “In Philly the shows were great,” Vosse says. “One night they opened for Three Dog Night and one night for Procol Harum. Procol Harum’s road manager was Nick Brigden, who has since become a big shot at Bill Graham Presents. He was the sweetest and most professional guy. That night everything got done well because Bridgen took care of it. I hadn’t been on the road much and I thought, ‘Oh, my God, this is the way it’s supposed to go.’ It was all done simply and professionally. They got the equipment ready and did a sound check, and none of this was being done with Phil.

“The band felt good because it was a much bigger crowd. Three Dog Night was huge then. It was a good audience, and they played well at both of those shows. They weren’t intimidated, but goaded that this crowd would expect them to do a good job. We went to Philly from New York—from catastrophe to that.”

An entourage member remembers the groupie habits of the Burritos on tour: “Philly was the only place on the tour I remember Gram not sleeping with floozies. The rest of them would go for groupies except for Ethridge. He was chaste. Gram never did groupies. He would go to bars and pick up [hardcore bar girls] who were older than him. Keith Richards talks about these hardened bar girls in Topanga Canyon who would cry when Gram sang. Gram was drawn to these people. They were soulful to him. And they didn’t have an agenda. They didn’t know who the fuck he was and he was drunk by the time he made his choice anyhow. They would be in their thirties and not particularly beautiful. You wouldn’t see them. They would be gone the next day.

“On the road, Hillman always had your prototypical groupie. They almost all looked the same…the long hair…find a picture of a little hippie girl from that era, there you have it. Ethridge, no. Pete, no. Michael Clarke, sure, but it would be whoever was willing to go home with him because he was so drunk. Gram separated himself from everybody. I never saw him at the hotel playing poker. The others would keep their girls around, but not him.

“But in Philly, Gram had a little filly. He had a little blond colt. And things got way out of control. She was like sixteen or something, and people had to get her the fuck out of the hotel. Flash forward to the next night backstage: I was called back to the door because there she was with her parents to meet Gram. We kept it away from him. That was the only time that I remember him going for a groupie that came up after the show—she was really, really cute. I remember saying to someone, ‘What the fuck? Is that a twelve-year-old?’ [Usually] he didn’t dabble in that area because he’d get drunk and couldn’t tell about age. Gram would go to a bar and find some hardened woman with a face all lined with sorrow and he’d be happy.”

On their last night in Philly the Burritos played a local TV dance-party show. They wore their turbans and Nudie suits and mimed to “Christine’s Tune (Devil in Disguise).” Chris Ethridge and Michael Clarke switched instruments; Chris faked the drums and Michael the bass. Footage from the show can be seen in Gandulf Hennig’s Gram documentary, Fallen Angel.

The tour ended unhappily. “We got to New York and discovered that the managers hadn’t gotten the right work permits,” Gram said. “So we had to turn around and return to L.A., starving and in debt. We burned a lot of bridges when we left, like leaving unpaid phone bills and stuff.” The work permits reference New York musicians’ union requirements, but Gram was finding any excuse for the catastrophe of the tour. Between the bills for drugs and expensive hotels and the missed showcase in New York, A&M had had enough. They canceled further support and promotion for the band.

CHRIS HILLMAN FOUND another house to share with Gram, a new Burrito Manor, on La Castana Drive in Nichols Canyon in the Hollywood Hills.

Hillman also asked Byrds road manager Jimmi Seiter to work for the Burritos. After the nightmare of New York, Gram wanted Seiter to comanage the band with Phil Kaufman. Seiter was reluctant. “Gram insisted that Phil and I be partners in managing the band,” Seiter says. “I didn’t want that. Hillman didn’t want that either. The management contract was signed by everyone but Gram. He didn’t sign it when it was time. Gram didn’t want to sign anything with anybody because of his bullshit with Hazlewood.”

The Gilded Palace of Sin was released in the midst of the tour, in February 1969. It reached #144 on the charts. It’s estimated that fewer than forty thousand copies sold.

Despite the crap sales, some contemporaneous critics recognized the worth of the album. “This album quite clearly stands as a complete definition of the term country rock, using a heavy instrumental approach combining strong country roots,” John Firminger later wrote in Country Music Review. “The lyrical content showed a departure from the more traditional subjects and involved topicalities like drugs, draft dodging, and sex, matters that the younger generation could readily identify with as part of their life styles.” When Rolling Stone asked Bob Dylan to name his favorite country-rock band, he answered, “The Flying Burrito Brothers. Boy, I love them. Their record instantly knocked me out.” Allan Jones, writing for the influential British rock weekly NME (New Music Express), raved, “Let me discourse on the sheer magnificence contained within the micro-grooves of Gilded Palace of Sin.”

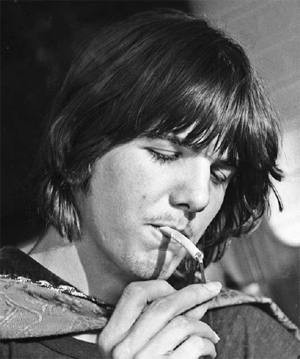

Gram, Bonnie Muma, and Robert Parsons. (© Andee Nathanson, www.andeenathanson.com)

Stanley Booth, writing in Rolling Stone, showed greater prescience and understanding than any critic of the time. He so captured the valence and intent of Gilded Palace that his arguments have framed the critical discussion of Gram’s music ever since. After citing Sweetheart of the Rodeo as “one of the best records of last year,” Booth wrote that Gilded, though possessed of “less surface charm,” “is the best, the most personal [music] Parsons has done.” The album, Booth noted, is about the temptations of urban life and the suffering of a man who finds himself at home neither where he came from nor in the city he has escaped to. Exploring these themes in a song-by-song analysis, Booth concluded that the album’s final cut, “Hippie Boy,” “summons up a vision of hillbillies and hippies, like lions and lambs, together in peace and love instead of sin and violence, getting stoned together, singing old time favorite songs.”

Despite Booth’s rave in the most important rock magazine in America, airplay was hard to come by, especially with no support from the label. The common wisdom of the album’s poor commercial reception is that the rock audience found the Burritos too country and country music listeners dismissed them as too hippie and rock and roll. There may be some truth to that view. The album’s slapdash production and cheap, tinny sound did not help. Among all the records that remain such major influences on the course of American rock and roll, Gilded Palace is the most shoddily produced.

Gram, playing the street-tough artist, told Fusion magazine, “They’ve let us follow our concept. They are in it for the money like every other record company, and if people start buying our records they’ll let us run with the ball. If I have to pay more dues I’m willing to, because I dig honky-tonk and rock ’n’ roll—and being on the street doesn’t bug me at all. I don’t need to have an image. So it doesn’t matter, one record company or another.”

Back home, the Burritos played regularly at the Palomino. They were heckled often—“Get off the stage, goddamned queers”—but their renditions of Porter Wagoner and Conway Twitty songs won the crowd over.

The band got a more welcoming reception at the hippie-oriented Topanga Corral. Byrds roadie Carlos Bernal was there. “When the Burrito Brothers hit the stage with ‘Six Days on the Road’ at the Corral in Topanga, the girls were beyond themselves,” Bernal says. “They left their tables as if hypnotized. They left their boyfriends. They left their drinks, they left their drugs. They had to get onto the dance floor and start dancing. It was an ocean of the cutest girls in high heels and miniskirts. Ask any other drummer and they’ll say, ‘Michael Clarke was a hack.’ But if you ever had Michael Clarke playing drums behind you, you didn’t need to worry about a thing. He was a performer’s drummer. You never had to worry about the beat not being right up your ass. It was a driving force. The girls were in a frenzy. Our frenzy was country rock at a loud level. It was a sexy sound.”

Gram onstage in 1969. (© Andee Nathanson, www.andeenathanson.com)

Around this time, Earl Ball ran into Gram at the Palomino. “He wanted to talk and I wanted to talk to him so we leaned up against a car and chatted,” Ball says. “I looked at his suit. He told me, ‘I’ve been over to see the Rolling Stones and I’m getting them interested in country music.’ He was telling me he was going to pull this off…the youth was ready for it and it was going to be the next big thing. It was going to happen. He had the Rolling Stones on his side. He was real positive.”

In March 1969 the Burritos opened for the Grateful Dead in San Francisco. The Dead and their consorts were well-known for dosing those around them with LSD. It was unwise to eat or drink anything in the Dead’s proximity that you didn’t bring yourself. The San Francisco show was going well until someone gave Sneaky Pete a Coca-Cola that was, unbeknownst to him, laced with LSD. Of that there is no doubt. What happened next is disputed. A less reliable source claims the acid hit Sneaky in mid-set, that he freaked out onstage, crying, “Whoop, whoop, whoop!” as he played the steel, and then walked from the Fillmore to Marin County and back. A more credible source reports: “It was scary. Pete went from never, ever doing drugs to being fully dosed with acid. He had to be taken to an emergency room and given downers.”

Gram was not thrilled to be compared to the San Francisco bands. When asked if his group shared communal housing like the Dead and the Airplane, Gram answered, “No, we’re not wife swappers and we’re not faggots, so why live all in the same house together with the same old ladies with all those temptations hanging around?”

Gram and Hillman wrote “The Train Song” during the tour. Back in L.A. they called in Larry Williams and Johnny “Guitar” Watson to produce it in a one-song recording session. Gram and Chris wanted an old-time R&B authenticity for “Train Song.” What they got was a hard lesson.

Watson and Williams incarnated gut-bucket R&B roots. Williams’ first hit was “Short Fat Annie.” He followed it with “Boney Moronie” in 1957 and “Dizzy Miss Lizzie,” both of which he wrote. The Beatles covered “Dizzy Miss Lizzie” and almost everyone covered “Boney Moronie.” Williams’ royalties enabled him to become a heavy drug user. He was shot to death in 1980.

Watson’s first hit was a 1955 cover of Earl King’s “Those Lonely, Lonely Nights.” He played with R&B bandleader Johnny Otis (father of guitar prodigy Shuggie) and in 1962 charted with “Cuttin’ In.” He and Williams toured the U.K. in 1965. Together they hit with “Mercy, Mercy, Mercy” in 1967. In the seventies, Watson cut two idiosyncratic funk albums highlighting his wailing guitar and yielding the hits “Ain’t That a Bitch?” in 1976 and “A Real Mother for You” in 1977. Watson was a fearsome character who pimped to support his career as a session guitarist and producer. Or, rather, he played guitar when he could be called away from pimping.

In hiring Watson and Williams, Gram and Chris sought a link to the pure R&B they loved and covered in their live shows. Clarence White and Leon Russell played on the session, which turned into a drug-fueled circus. The Burritos felt like poor hosts when they had no weed to offer Watson and Williams. After the band apologized, Watson pulled out a fat joint. Referring to a popular margarine ad in which crowns magically popped up on people’s heads (“Taste fit for a king!”), Watson said, “I call this the butter. It’ll make you feel like you’re wearing a crown.”

Watson and Williams reportedly spent their time in the control room doing drugs and ignoring the band. According to Phil Kaufman, instead of injecting soul into the proceedings, the two producers sat in the control room doing lines of cocaine and saying, “Sounds great, guys. Sounds great.”

Leon Russell finally took over the board to make some sense of the chaos. Gram, as the paying customer, could have held Williams and Watson to a professional standard, or fired them on the spot. Instead, he snorted right along with them. “It was terrible! I was so embarrassed,” Jimmi Seiter says. “That’s the demise of the Burritos in my mind. All Gram wanted to do is have fun, party.” Burritos insiders agree with Seiter. For Hillman the sessions represented the peak of Burrito excess and indulgence, the end of a pure period of writing, recording, and playing the sounds they heard in their heads. It also ended Gram and Hillman’s dream of directly incorporating the R&B they loved into their music. The two worlds would not merge as easily as Gram and Hillman had thought.

Gram’s behavior was characteristically passive and destructive in the face of dashed hopes. He did nothing to rein in Williams and Watson; he endorsed their antics by snorting with them. He could have taken action but instead encouraged events to spin out of control. To be produced by two obscure R&B legends was Gram’s dream, but he declined to pursue the dream when it did not magically unfold.

Chris and Gram moved again, to Beverly Glen Drive. This house, too, was known as Burrito Manor, and the atmosphere was hardly different from the Manor’s previous address. “Strange women coming in and out, a lot of powder, liquor,” Hillman recalled later. “Gram was drunk and stupid a lot…. He would go up to some chick at the Troubadour and say, ‘Hel-lo, senorita.’ He had these big, sincere, brown eyes. We were hoodlums then, really the outlaw band.”

Being consistently underappreciated and forced into an outsider role led the band to develop an ethos to go with their clothes and repertoire—and their refusal to be professional about rehearsal. “We were musical rebels,” Sneaky Pete says. “We didn’t play according to any slick concept. We played rough, as we felt it. We were an outlaw band because we weren’t accepted by audiences or by our peers and contemporaries. A lot of musicians in other bands were derogatory in their remarks about us.”

“We’re the only true outlaw band,” Gram said. “Why? Because we’re treated great in one way and, on the other hand, we’re completely misunderstood. Rock critics and country critics completely misunderstand—it would be the same with R&B critics if they had the opportunity.”

Years later, Hillman reflected on how the Burritos’ outlaw style, musical and otherwise, set the tone for other bands. Glenn Frey, soon to be a founding member of the Eagles, was half of the duo Longbranch Pennywhistle. The other half was producer and songwriter J. D. Souther, who later formed a band with Hillman and Richie Furay. The Pennywhistle sometimes opened for the Burritos. Frey claimed he “learned a lot about stage presence and how to deliver a vocal” from watching Gram and the Burritos, according to Hillman. “Don’t think Glenn Frey wasn’t in that audience studying Gram. He was. And it is nothing bad. I have all due respect for Glenn and the Eagles. I think they are great. But they are an extension of the Burrito Brothers outlaw thing, an extension itself of the Byrds–Buffalo Springfield family. It’s a heavy family tree.”

Playing redneck clubs and low-down dives was key to the Burritos’ outlaw self-image, but it was also a fact of life. The band had once loved dives; now they had few other options. The two former Byrds felt they had too much stature to go back to playing second-rate venues, however romantically low-rent they might be.

“They couldn’t get booked anywhere,” Jimmi Seiter says. “They’re not country, they’re like a bastard son. They would book us these gigs and the venue would be expecting a pop band and we’re a rock band or country band or vice versa…. At rock festivals we were well received. But we weren’t country enough to play at a country nightclub…Gram didn’t mind playing the pop festivals, but he didn’t like playing clubs. Hillman didn’t like it either. Hillman had never played clubs before. When the Byrds played clubs they played the biggest clubs in Hollywood. The Burritos played shitholes, places in Colorado Springs. Hard-to-find places out in the middle of nowhere. Try to play ‘Hot Burrito #1’ for a country audience. They go, ‘What the fuck is this? Fuzz steel guitar? Get out of here!’

“They could play country. And a couple of times they had to redo the Burritos style and play a full-blown country set. They’d pull out the acoustic instruments and wing it. Fortunately for them, country songs are kind of easy. Like three chords and out. As long as you know the words you’re cool, and Gram knew a lot of them.”

“We played anywhere,” Sneaky Pete says. “High schools, grade schools, junior proms, even prisons. They loved us at the prisons. But generally audiences didn’t respond to us. We ended up in a black club that had just switched over the clientele and was not amused by our Nudie suits. They walked in and said, ‘Man, what is this shit?’ and then walked out.”

Gram naturally put a positive spin on their circumstances. “There is a good music scene in L.A.—a lot of good musicians have been playing together lately,” he told an interviewer. “But it’s not so much at the Whisky and places like that as in the honky-tonks out in the Valley. Groups like Delaney & Bonnie, Taj Mahal, the Tulsa Rhythm Revue. A lot of funky people coming from the South—Texas, Tennessee, and Tulsa—coming out to L.A. to make a little dough, and they find out you can’t because there aren’t many clubs in L.A. to play at…Snoopy’s Opera House, Peacock Alley, the Laurel Room, the Prelude, the Palomino, the Aces Club, and the Red Velour and the Hobo, clubs that nobody knows about in the San Fernando Valley, the City of Industry, Orange County. The clubs out in the Valley are honky-tonks and funky, nicer than the honky-tonks in Nashville, because the people are less liable to rap on you for having long hair. They see more of it and you can go out there and boogie all you want. That’s the most positive thing I can think of about L.A., these places out in the Valley—the most negative thing I can think of is the Strip itself…with all the people addicted to carbon monoxide.”

Gram was frustrated with the Burritos’ lack of success and the country-rock acts springing up in their wake. Michael Nesmith of the Monkees was making authentic country records; Poco’s first album, a sort of country-rock lite, was well received. San Francisco’s Moby Grape had begun a Bay Area movement away from psychedelic jams toward tighter, country-inflected material. The market was starting to embrace a variety of emerging country-rock forms, but not the Burritos.

“We paid a lot of dues, but we dug it,” Gram said. “While everyone else was going to the Whisky building up their egos, we were saying, ‘Jesus Christ, man, nobody likes us! What are we doing?’ We were going out to clubs and to forget our troubles we were getting smashed and rocking ’n’ rolling every night as hard as we could. Nowadays everyone wants to get in on the bandwagon, everybody wants to say they are country, including Bob Dylan, who I dig and respect, but he’s not as country as Crawdaddy [a national monthly rock magazine, now defunct] seems to think he is. Now [the critics and rock writers] are trying to project this country scene onto him. And Dylan isn’t country…he’s a poet.”

Gram spoke to the fuss raised over their sequined suits. “We think sequins are good taste,” he insisted. “Rolling Stone, the Free Press—they think that we’re a bunch of show-offs and we’re trying to put everything down. We’re merely reflecting everything because real music is supposed to reflect reality. You can’t build a reality in music, you have to reflect it. Like ‘original’ music was made to get people together. Like religious music, to form a bond between you and your ancestors, let’s say. In church you would have music that would make you nostalgic and think of the olden times and what the reality was that led you up to right now. That’s where music is at. You can’t build your own reality—that’s why psychedelic music is so jive. It’s everybody’s own bag. No, I’m sorry, you know, we’re all in it together. Like it or not.”

Gram was making his case for Cosmic American Music and stating the facts. Real country musicians wore sequins. Gram loved the sequins for their absurdity, and he loved them sincerely. The L.A. country rockers following Gram thought boot-cut jeans and cowboy boots were a uniform of authenticity. But in the world of real country, the blue-jeaned boot wearers were the poseurs, and Gram had it right.

“They’re so uptight about our sequined suits,” he said. “Just because we wear sequined suits doesn’t mean we think we’re great, it means we think sequins are great.”

IN THE SUMMER OF 1969, Gram left Burrito Manor and moved into the Chateau Marmont Hotel on Sunset Boulevard. He shared an apartment with Tony Foutz. When Gram moved out, Chris Hillman left to share a house with Bernie Leadon in the nearby beachside town of Venice.

Eve Babitz was an astute observer of and participant in the Sunset Strip scene. Like Andee Nathanson, Eve hung out in the music and movie worlds and dated musicians. A remarkable writer, she had a column in Esquire when she was nineteen and Esquire was the best magazine in America. She became a close friend of Gram’s and later portrayed him as a character in her fiction. The chapter “Rosewood Casket” from her first collection of stories, Eve’s Hollywood, describes Gram’s magical presence when Babitz first met him, and his later decline.

“When I first met Gram he was wearing a blue blazer and white pants,” Eve Babitz says, “and then it was, like, cowboy boots and Indian outfits and serapes. Gram was the perfect Hollywood person. He was so beautiful and a stranger from the South. I was amazed by him. He had charisma. He was like Elvis. I never met Elvis, but Gram radiated charisma. I had seen a lot of people with charisma by that point. There’s a tradition in Hollywood that we try to protect people who are going to be actors and stars from whatever’s going to go wrong with them. We try to keep them safe before they either go insane or die. When people have charisma, other people take care of them around here. They could get away with murder.” As for Gram’s mission to bring American roots music to resistant audiences while wearing a sequined suit: “He was so beautiful he got away with it.”

Gram around the time he moved into the Chateau Marmont. (© Andee Nathanson, www.andeenathanson.com)

When Gram moved into the Chateau Marmont, a room in the hotel cost only twenty-six dollars a night. “The Chateau Marmont is elegant,” Eve says. “Greta Garbo lived there. It’s intense and behind the scenes. Quiet. It was beautiful. Gram was perfect in it. It was as beautiful as he was.”

Eve points out that the hotel was part of a cluster of old-time Hollywood landmarks. The Garden of Allah apartment complex, where F. Scott Fitzgerald, Robert Benchley, and other literary and film celebrities lived, was across the street. Down the road was Schwab’s drugstore, a meeting place for old Hollywood where Lana Turner was supposedly discovered. “The Garden of Allah was torn down in the fifties and all the ghosts went over to the Chateau,” Eve says. “So the Chateau had this ancient patina. Of course, Hollywood has only been here since 1903. But the Chateau seemed to have five hundred years of history.”

With its separate self-enclosed bungalow apartments and thick, soundproof walls, the Marmont offered more privacy than the average hotel. “I once stayed next door to the country-rock star Gram Parsons, a man whose consumption of drink, drugs, and women was legendary, as were his good manners,” a British journalist wrote. “Indeed, he was very pleasant in the corridor, and for all the sounds I heard from his rooms he might as well have been at his prayers.”

Andee Nathanson first met Foutz when she was eighteen and working as a model at Jax, the Beverly Hills fashion house. “The Chateau was hilarious,” Andee says. “It was like a well-located rooming house where the inmates were running the institution.”

“It was like a rock-and-roll hotel, but rock-and-rollers would change where they lived every five minutes,” Eve Babitz says. “They never lived there, except for Gram. They would buy one house here, one house there. The rock-and-roll scene was in Topanga, and they were out at five in the morning. Nobody ever lived anywhere. Gram was a bastion of stability, considering.”

Another worldly character in this scene was Prince Stanislas “Stash” Klossowski de Rola, son of the reclusive French painter known as Balthus. Discovered by Italian director Visconti at seventeen, Stash became an actor. In 1963 he went to Paris and played rock and roll with Vince Taylor, a performer credited as the inspiration for David Bowie’s Ziggy Stardust. In 1965, on tour with Taylor, Stash befriended the Rolling Stones and became close with Brian Jones. It was on the same tour that Jones met Anita Pallenberg, who had been hanging with Taylor’s band. Jones and Stash were busted together for drugs in 1967, further cementing their friendship.

Stash and Tony Foutz became acquainted in Rome, where both stayed at the Villa Medici. Stash moved frequently: L.A., Paris, Rome, and the Moroccan mansion of playboy John Paul Getty and his iconic bohemian wife, Talitha. Stash was one of the first prehippies to make the pilgrimage to India to study meditation.

“It was rather seedy and very much a home,” Stash says of the Chateau. “The Chateau Marmont was full of artists and longtime residents. It was the Chelsea Hotel of the West Coast.”

“The Chateau was a den of iniquity,” Eve Babitz says. “I would always leave before things got too weird. I would figure things are falling apart and I should leave.”

Even in this star-studded setting, Gram stood out. Just as he found a way to bring together the sex of rock and the pain of country, Gram combined the glitter of old-school Hollywood with the new hippie glamour. A glamour he helped create and codify.

“When I grew up, the bohemian community was in San Francisco, and L.A. was this square place where nothing ever happened,” Eve says. “L.A. was as isolated as an Iowa farmer town. They believed in stardom and sequins and rhinestones. And they took it seriously.”

As a connoisseur of the L.A. scene, Babitz was fascinated by Gram and recognized that he incarnated something magically, classically Hollywood yet totally brand-new.

“I was so into Gram’s looks,” she recalls. “I couldn’t see anything else when I was around Gram. I couldn’t see other people. I told him I wanted to come over and take pictures of him and he said, ‘You have to wait three days so I can lose some weight.’

“I would make him get dressed up and take pictures. But his ex-girlfriends and wife would tear them up when they left.”

Gram and Foutz’s apartment number was 4F—as visitors often remarked, the same designation as Gram’s unfit-to-serve draft status. John Phillips’ wife, singer Genevieve Waite, another Swinging Londoner, recalls that the door “had these incredible graphics that said: ALL ABOUT GRAM. I had never seen graphics like that: this great printing of spacemen all over the door. It was cool.”

Linda Lawrence moved to L.A. from England with her son Julian. Julian’s father was Brian Jones of the Stones. Linda met Gram at the Chateau. Shortly after, Linda and Julian moved in with Gram. The affair lasted a few months. Linda later went on to marry the hugely successful folk-pop singer-songwriter, Donovan Leitch.

“Train Song” was released in July of 1969. It garnered no airplay or sales.

On August 9, 1969, the sixties came to an end in Los Angeles when Charles Manson’s long-haired minions murdered actress Sharon Tate and four others at the house Sharon’s husband, director Roman Polanski, had rented from Byrds producer Terry Melcher.

“It was the end of the innocence,” Andee Nathanson says. “In Hollywood, in music, film, in L.A., that wasn’t supposed to happen. That was the bogeyman coming out. The energy shifted, from a sense of connection to, ‘Oh, my God, there’s crazy people out there that can kill you.’ In all this innocence and all this love, it came crashing down. The bubble burst. I’ve heard rock-and-roll people say, ‘Let’s not get too real.’ But that’s about as real as you can get.”

Manson burst the bubble for the originators of the sixties. A few days later, on August 15, Woodstock demonstrated the market penetration of the longhair lifestyle. The size of the Woodstock audience—almost five hundred thousand strong—shocked the business world into understanding how much money could be made from the notion of a counterculture. Simultaneously, Manson’s crew established that the trappings of the hippie lifestyle could be extended—for better or worse—in directions other than peace and love. As the groovier Angelenos reeled from their new perspective on the dark side, the movie Woodstock was about to convince the American public that the brotherhood of hippie-dom was alive and well.

Woodstock, the movie, brought the concept of an alternative community held together by rock and roll and drugs to every small town in America. At Woodstock, the festival, Joan Baez played “Drug Store Truck Drivin’ Man.” The song was not included in the film.

THE ROLLING STONES returned to L.A. on October 17 to mix Let It Bleed and prepare for their 1969 tour of America. They moved into several L.A. houses, including Stephen Stills’ estate—which had earlier been home to Monkee Peter Tork and his legion of naked girls. Phil Kaufman had to eject Stills, who didn’t want to leave because he was ill, and his drummer, Dallas Taylor, who was drunk.

Writer Stanley Booth, later the author of The True Adventures of the Rolling Stones, met Gram shortly after the Stones arrived in L.A. He and Gram both hailed from Waycross, but hadn’t known each other there. In his book, Booth describes Keith and Gram coming in from a tennis game and singing country tunes together around the piano, with Mick Jagger joining in. Added Booth, “Mick didn’t look sure he liked it.”

“When the three of us sang together, it sounded like Gaelic music. Like the Incredible String Band,” Gram said, referring to a popular English group given to sophisticated hippie sentiments and exquisite harmonies with an Olde English feel. “On one occasion at the piano with me and Jagger and Richards, there was Little Richard. ‘It’s all the same,’ that’s what Keith said. Two Georgia peaches and two English boys, stinky English kids…. It’s far out and drunk.”

“Gram was one of the few people who helped me sing country music,” Mick Jagger recalls. “The idea of country music being played slightly tongue in cheek, Gram had that in ‘Drug Store Truck Drivin’ Man,’ and we have that sardonic quality, too.”

At Gram’s urging, Mick and Keith hired country fiddler Byron Berline for “Country Honk,” the countrified album version of their cowbell-driven single “Honky Tonk Women.” Byron had played with the Dillards and recorded with Dillard & Clark; he and Gram met when both were recording at A&M.

As Berline tells it, the emerging country-rock scene in Los Angeles was like “a big family,” with everyone playing, experimenting with, and enjoying the same kinds of music. “Country music, rock-and-rolly stuff,” Berline says. “I get a phone call from the Rolling Stones. They called real late at night and were mumbling, ‘Hey, we’re the Rolling Stones.’ I asked, ‘The magazine?’ ‘No, the group.’ Finally I figured out it was Keith Richards and Phil Kaufman on the phone. I said, ‘Well, I’m gonna be out there in about six days.’ They said, ‘No, no, we want you out here tomorrow.’ So I flew out of Oklahoma City.”

Berline played the song with the band a few times in the studio. He was told, “We have this idea to give it a little ambience—we’ll take you out to the sidewalk and record it there.” His track was recorded on the sidewalk. Berline learned that he’d been called because, “Gram tried to talk them into doing it more country, so they decided to use the fiddle on it. That was a big shock to me. That helped my career.”

The song does have a powerful outdoor ambience. It opens with the sound of wind, an acoustic guitar, and an iconic double car-horn honk as Byron spirals in the opening fiddle lick. Phil Kaufman later claimed he’d hired a woman to drive by and repeatedly hit the car horn.

Gram took the Stones to his favorite haunts. One night the crew turned up at the Topanga Corral. Gram and the Burritos played and sang and everyone whooped and drank beer. According to Stanley Booth, the evening reminded the Stones of the good old days when they had played in down-and-dirty clubs. “Now, getting ready to get back on the road,” Booth wrote, “it was good to be at the Corral and see all these different types, motorcycle boots, eagle tattoos, lesbian romancers, white English [singers], Beach Boys, Georgia boys brought together by the music.”

Gram, Andee, Keith, and Anita flew to Las Vegas to see Elvis Presley. It’s impossible to overstate how unhip Elvis was at that point. He incarnated everything destructive about the effects of show business on rock authenticity. “Gram was so excited, he was like a little kid,” Andee remembers. “I’ve never seen him so animated…. Gram was almost out of his seat, jumping up and clapping when Elvis appeared in a white outfit with sequins and all the little old ladies in front were so excited—it was electrifying. We met Elvis afterwards backstage. I think it was one of the great highlights of Gram’s life, and amazing to see them together.”

Gram was constantly high. “I would spend days taking drugs with Gram,” Eve Babitz says. “I thought he was always on drugs. He had huge bottles of drugs—jars filled with Demerol and Placidyl [a sedative and hypnotic whose production in the U.S. was discontinued in 1999] and Dexamyl [an amphetamine combined with a barbiturate] and stuff you shouldn’t be having. Stuff that would keep you up all night and all day. His friends were over and they all took them. I took as many as I could. Meth was the worst. You can write War and Peace but you can’t sit down. I would hang around, take drugs. We would wait all day for somebody to bring the grass…. That’s what people did in those days if they could afford it.”

The creative abuse of substances was another interest Keith Richards and Gram shared. “Gram was as knowledgeable about chemical substances as I was,” Keith says. “I don’t think I taught him much about drugs—I was still learning myself, much to my detriment. I think we were both basically into the same thing. He had good taste. He went for the top of the line. We liked drugs and we liked the finest quality. He could get better coke than the mafia.”

Throughout the Stones’ history, plenty of others liked drugs of the finest quality and tried to hang with Keith. Keith’s constitution is legendary, and no one who tried to match his drug consumption (or his appetite for staying awake days on end) could, in the final trial, stay the course. Stanley Booth wrote, “I decided that if Keith and I kept dipping into the same bag, we would both be dead.” Booth flatters himself. If the historical record is any guide, only one of them would be.

That’s not to imply that Keith bears any blame for Gram’s drug use. No one ever lived on Keith’s schedule for any length of time except Keith. What may have seemed like normal life to Gram was in fact junkiedom at the most taxing levels of consumption.

As for precisely when Gram added regular heroin use to cocaine and pills, no one remembers a Eureka! moment. No one describes being shocked to discover Gram using. No one suggests that Keith introduced Gram to shooting up. It struck Gram’s friends as inevitable, another step on the path.

“This whole generation has been into heroin, which I’ll never understand because it’s the worst drug on the planet,” Miss Mercy says. “Even though I’ve done it, I was never into it. L.A. was a wonderful place…but there were too many drugs. Everything was too drug oriented. At that point everyone was on downers and drinkin’. It was kind of sloppy—all Seconals and Tuinals.”

In a milieu where roots and authenticity—and relentless ego competition—loomed so large, the move from prescription downers to the baddestass street drug was, for the committed, almost unavoidable. In the immortal words of Keith Richards, as told to John Phillips, “Pharmaceuticals are for pussies.”

Well-off users assert that heroin, among the major addictive drugs, is not so bad for you. As long as you buy first-rate junk, as long as you don’t suffer withdrawal or do unreasonable amounts, their argument goes, heroin is manageable. It’s the withdrawing and becoming readdicted and withdrawing again that wrecks your health. That and not having the money or connections to buy clean shit. And for some, Keith Richards among them, it seems to be true. “Remember,” Richards once said, “I learned to ski on heroin.”

If your main heroin partner is a guy with those capabilities and attitude, then devoting yourself to keeping up is a dangerous decision. But Gram liked heroin, and nothing in his financial circumstances made addiction difficult for him. Gram never claimed to be a tormented addict. He often said he had no desire to quit.

Genevieve Waite came to a Stones session with John Phillips, who had drug problems of his own. “We went to the recording studio and Gram was there,” she says. “Everyone was on junk and John was really mad at him. John said to me, ‘We’re getting out of here!’ And I said, ‘John, why do we have to leave?’ And he said, ‘Well, everyone is on junk.’ John was trying hard not to be around it.”

Miss Mercy recalls the day that Jimi Hendrix’s girlfriend, Devon Wilson (the inspiration for his “Dolly Dagger”), came pounding on her door saying, “Keith sent me here for me to find Gram.” Miss Mercy took them to Gram’s place. “We found Gram playing with his fucking needles,” she says. “He was that far gone. Taking a lightbulb wire to clean out his needles so he could fix. But he was all excited that Keith sent Devon. Devon wanted to find Gram for heroin, and the heroin was there.”

“John [Phillips] was not a member of the Gram Parsons fan club,” Genevieve Waite says. “He was hard on Gram, like an older brother. He loved Gram and he loved his voice, but he wasn’t like a lot of people who were Gram sycophants. Gram was doing junk long before John started, and John hated it. He loved him, but he wasn’t going to ease up. Gram would come over to all our different houses and John would say to him, ‘What are you doing with the Stones? Why are you doing this?’”

The drugs, music, and elegant graveyard wit that Keith and Gram shared seemed only the signposts of a deeper bond. The two were so enmeshed that boundaries separating their two personalities began to erode.

“Gram and Keith were kind of in love,” Pamela Des Barres says. “I’m sure they never did anything physical, but they had this incredible mutual-admiration society. They understood each other and wanted to take parts of each other and make them their own…. They took different pieces of clothing from each other and traded. Gram started wearing makeup like Keith and Keith started wearing Nudie belts. It was incredible to watch.”

“Gram got so overtaken that he started turning into Keith,” Miss Mercy says. “It was crazy. Gram was just like Keith and Keith was just like Gram. They switched accents and they switched clothes. Gram was running around stage with his wrist [flapping] and acting so odd that people would roll their eyes up in their head. We were like, ‘Oh, my God, this is frightening what’s happening to this poor guy.’

“He had a limp wrist. That’s how influenced he got by Keith. He was acting like he was English and gay. You know the rest of the Burritos thought he’d flipped his lid. At the Troubadour, Gram started putting all this English stuff on and Keith was giving him clothes. Keith was getting more Gram-y. They changed identities, basically. Gram was almost getting an English accent and Keith was getting a Southern one. They were inseparable. Mick was annoyed.”

Pamela Des Barres wrote at the time: “Keith scared me; he’s like a foreign object and Gram is becoming his clone.” “The time he was spending with Keith didn’t have a very good influence on him over the long term,” Jet Thomas says. “It made the other [Burrito] members feel left out.” “Gram stuck out like a bleeding thumb in satins and nail polish,” journalist Rick Cusick says. “The rest of the Burritos wondered where he got the balls.” “Gram wanted to be in the Stones,” Bernie Leadon says. “Onstage with us he’d take off these scarves and start dancing like Jagger—with this country band! Hillman called this Gram ‘Mr. Mystique.’ But I liked him. The cat had balls—he didn’t care.”

“Chris didn’t like that—he didn’t get it,” Jimmi Seiter says. “One night, they played the Whisky, which was a good gig for them, and Gram arrived late, with his eye makeup on. You can’t imagine. Chris had this manly thing about him and Gram showed up with makeup and Keith’s scarves and belts. He started acting like Keith onstage—eventually he drop-kicked his guitar across the room, into the wall at the other side of the club. By that point Chris had turned his back.”

“The Rolling Stones got in the way tremendously,” Hillman says, “because Gram was like a groupie. ‘Oh, sorry guys, but I’ve got to go hang out with the Stones now.’ The times I picked him up at Keith’s house were a little strange. They’d come skipping out like kids.”

“Chris and I were living in this little house down at the beach, riding our bicycles and trying to be healthy,” Bernie Leadon says. “Chris and Gram were living different lives.”

Gram’s different life was wreaking havoc on his performances and his relationship with Hillman. “Sometimes Gram was fine in that drunken, good-old-boy, sorrowful voice of his,” a source recalls. “Other times it would be fragmented and you could see how angry Hillman was. A lot of shows weren’t as good as they should have been. A lot of recording sessions that could have been better. But there were also a lot of recording sessions that were fine.”

“[Gram and Hillman] both loved the music and worked together musically,” Jet Thomas says, “and during a certain period of time they were buddies with their motorcycles and Chris’ little pickup [truck]. They hung out together, but ultimately they were different people. I’m not surprised that over a period of time those differences became greater.”

Gram and Keith’s bonding caused strains for another partnership as well. “My only problem with Gram was Mick,” Keith says. “For some reason Mick has a hard-on about me. He’ll get incredibly shitty against anyone who appears to be getting too close to me…” According to Keith, he and Mick never spent that much time together outside of their work for the band. In Gram, Jagger had run up against what Keith called “a bigger gentleman. The biggest gent that I have ever known.” Keith resented Mick’s efforts to control who his friends were. Gram—as the bigger gent—reminded Keith that he had to get along with Mick.

Gram’s infatuation with the Stones, and Mick’s impatience with Gram, came to a head. The Burritos had a show to play, but Gram didn’t want to leave the Stones’ recording session. “I finally found him at the Stones session!” Hillman recounts. “I go in there to him and he’s going, ‘Ah, I don’t want to go.’ And Jagger got right in his face and told him, ‘You’ve got a responsibility to Chris, to the other band members, and the people who come to your show. You better go do your show now.’ He was matter-of-fact. I’ll never forget that. So Gram got up and went to the show.”

Jagger seemed to be the only person whose chastening made Gram behave more maturely.

Keith threw a party at Stephen Stills’ house for Gram’s twenty-third birthday, on November 5, 1969. One of the guests was sixteen-year-old Gretchen Burrell. She was a quintessential blond Southern Californian, an aspiring actress and the daughter of Larry Burrell, a conservative TV newscaster. Even by L.A. standards, where astonishing beauty is commonplace, Gretchen was astonishingly beautiful. She and Gram were immediately smitten.

Pamela Des Barres says of Gretchen: “She was a gorgeous model, a real beauty.” Miss Mercy found her stunning. Genevieve Waite says, “I met her once. She was in Gram’s room at the Chateau, sitting on Gram’s bed. She seemed like a happy, smiley, beautiful blond girl. She seemed happy with Gram and to love him.” Eve Babitz remembers Gretchen as happy when she first met Gram and then increasingly “pissed off.” Marcia Katz says, “He was heavy into drugs when he met Gretchen, so his whole involvement with her came from a drug-related state.”

In late November Chris Ethridge left the Burritos. He wanted to pursue his growing studio career. He later played with Ry Cooder, Linda Ronstadt, Jerry Garcia, and Willie Nelson. “I had never realized that Chris wasn’t a country bass player,” Gram says. “And it should have been obvious to me ’cause he’s such a great studio musician, but he’s not a country bass player. He realized it before anyone and said, ‘Wow, man, I’m sorry.’

“What we needed was somebody who could play country shuffle. Chris understood that, so he split. I suppose from the time he split I got sort of disillusioned.”

Even if it sounds like sour grapes, Gram’s assessment is accurate. Ethridge’s style inclines toward R&B and groove-oriented rock. His hands and mind are too busy for simple country bass playing. Ethridge tends to push the beat forward or lay back off it—slow-burn funk style—and neither works for country.

“I liked writing with him an awful lot,” Gram continued. “It blew my mind that he wasn’t the right bass player. And so when he was missing, it seemed the idea had been wrong, that we had picked the wrong people. And I didn’t know quite how to say it to Chris [Hillman] without getting in a fistfight about it. So I tried to stick it out, make it work, but…”

Chris Hillman moved back to bass. Bernie Leadon took over Hillman’s spot as rhythm guitarist. Leadon had played with Hillman in the Scottsville Squirrel Barkers, with the folk-country pioneers Hearts and Flowers, and with Dillard & Clark. He was a rhythm guitarist with an exceptional sense of the beat and the ability to blend driving guitar lines with the bass. He described himself as “a great utility infielder.” Leadon has skills and a singular cohesion; he makes any band sound tighter, their songs more energetic. That’s no small gift, and few have it. Leadon radiates an unshakeable air of purpose and bedrock sanity. Given that he later helped cofound the Eagles, one of the most popular bands in rock, remaining sane is no small accomplishment.

“The first album’s momentum had been spent,” Bernie says. “They had gotten a lot of critical acclaim, but they hadn’t sold much. Chris Ethridge had quit and now they’re a man short. Chris Hillman went back to playing bass and they call me.

“Gram was an incredibly charming, charismatic guy, and he made sure that people would look at him. He was dressed in an interesting, different way. He always had expensive clothes, scarves, and funny hats. He could afford a custom Harley [Gram had traded up from a smaller BSA] with a custom paint job and those clothes and to live at the Chateau Marmont.

“I was intrigued by all the music that Gram was listening to. He always had something on the record player or the tape player. He was the first guy that I knew that made custom tapes. He made mix tapes: He would have a bunch of different country people, R&B people, the Stones, the Impressions, Curtis Mayfield. He had a lot of obscure country stuff. He knew all these songs. He was a musicologist in that way. He knew the lyrics to hundreds of songs. He could always throw something out like, ‘Hey, let’s do this,’ and I was like, ‘What the fuck is that?’ He knew all this old country stuff and obscure R&B. He could pull it out of his pocket. He would start playing, or start strumming in some tempo or some key, and we would all fall in.”