CHAPTER 21

Bitter Ash

When the nineteenth century dawned in Venice, the widow Laura’s afternoon at the café Thistle seemed like ancient history. In a swift stroke, Napoleon had conquered the city with scarcely a shot. On May 12, 1797, under threat of imminent invasion and rumors of a planned bloodbath by Venetian revolutionaries, the Senate voted to dissolve the government. The Serenissima’s millennium of proud independence was over. Before the next carnival, among the welter of decrees from the tumultuous first year of the new order, would come an edict banning masks in cafés, streets, and other public places. With this, the small piece of waxed carton, the inscrutable public face of Venice for more than a century, vanished as abruptly as the Republic itself.1

Napoleon’s relentless drive through northern Italy had met little substantial resistance as city after city fell: Milan, Bergamo, Brescia, Mantua, Verona, Vicenza, Padua. When a skirmish in Venetian waters left a French commander dead, Napoleon seized the moment. An arrest warrant targeted the three State Inquisitors as the supreme authority. All other offices and magistrates were declared the “miserable instruments of [their] atrocities.” He raged to stunned envoys that he would tolerate no “inquisitions.” “Opinions must be free,” he told them, “and I will liberate every man who has been detained for his opinions.”2

Following the capitulation, the doge ceded authority to a sixty-member Municipality. Under the “protection” of more than three thousand foreign troops occupying the city, the body mimicked deeds from the rench Revolution’s earliest days. Noble titles were abolished, a National Guard was established, and elaborately didactic civic festivals were staged. Among the first official acts was a patriotic luncheon that culminated with the planting of a Liberty Tree in Piazza San Marco, a ceremony repeated over the coming weeks and months in neighborhood squares throughout the city. Sometimes fasces were erected on either side of the trees. An explicit French borrowing from ancient Rome, the cluster of sticks symbolized strength through unity. Another official act commissioned six stonemasons to chisel all lions off the city’s public facades as emblems of tyranny. When Venetians opposed to the new regime gathered in late July to protest, they were arrested. The Municipality then issued an edict formally outlawing opposition. It prohibited “incendiary” literature, forbade all acts of “insubordination,” and criminalized the cry Viva San Marco! The penalty was death.3

Public discontent seethed. Crowds vandalized the shop of a printer who displayed images of a lion enchained by Liberty. The principal instigator of this act of protest, a twenty-four-year-old named Antonio Mangarini, was sentenced to death by firing squad. The presence of foreign troops led to brawls, which were sometimes fatal. For having caused the deaths of two Frenchmen, the authorities made an example of two Venetians, Giuseppe Marinato and Sebastiano Panadella. They were also executed by firing squad. When Nicolò Morosini, a military commander from an ancient noble family, published a letter harshly critical of the Municipality’s direction, his property and possessions were seized, and he was banished for life. The case received considerable attention in the press, and the Municipality did its part to shape the story by publishing a decree that condemned Morosini’s “nefarious talents against the fatherland” and declared him to be “a felon and an enemy.” The decree was issued “in the name of the sovereignty of the people.” It was clearly intended to silence other critics.4

Propaganda rewrote the past business of the Venetian judiciary from hearing criminal cases to terrorizing its population. Didactic engravings were commissioned that featured chilling scenes: a Christlike figure stands nobly to hear his death sentence, a manacled prisoner is dumped into a canal as a priest looks cooly on, wretches in fetid cells soak in seawater or swelter beneath the prison’s lead roof. Pamphlets flooded public places describing the State Inquisitors as monsters and their deliberations as a chamber of horrors. One pamphlet, The Mask Falls, condemned “odious enemies of the fatherland” for their “pomposity, cruelty, ferocity, and inhumanity.” Another, Imposture Unmasked by Fact and by Truth, called the malice of the aristocratic republic a sin against the sacred laws of nature.5

Over a period of six months, members of the Municipality replayed key moments from the French Revolution. It created a Committee of Public Safety, called for the nationalization of patrician wealth and property, and proposed a renewed Reign of Terror to intimidate conspirators and purify the population. The latter plan, which was not acted on, would begin with the mass arrest of former government officials and the execution of ex-aristocrats and cittadini.6

Taken together, the moves to demonize the ruling class and punish counterrevolutionaries made reforming the Venetian political system—and not the billeting of French troops, pillage of cultural patrimony (twenty paintings, five hundred manuscripts), or substantial transfers of arms and money to France—the main story. French and Venetian negotiators agreed not to make public these latter terms.7 Napoleon possessed the ultimate secret, which staggered even his most ardent defenders. He held a tentative agreement, concluded before the Republic had fallen, to transfer a conquered Venice to Austria. In late January 1798, the French ceded the city to the Hapsburg throne, which nullified the ordinances of the Municipality, restored the rights of patricians, and, in the name of public tranquility and individual security, banned carnival and outlawed masks.8

Venice’s past as a city of masks and its carnival tradition were easily recast to fit the narrative. Both were declared symptoms of the Republic’s tyranny and marks of moral decline. Venice fell so suddenly because its extravagant pleasures, the mad orgies of a desperate people, had sapped the body politic of its vitality. Napoleon simply finished what the sickness had already begun. An official (i.e., Austrian-approved) newspaper account connected the dots, describing carnival as a poison that had infected its revelers and weakened their moral fiber. The language betrays morbid fascination.

I still remember the immense, ever-swirling vortex of disguised, masked people in a thousand-thousand fashions and forms blocking every entry and obstructing every street with the clamor of bacchantes. Each access vomited forth this proud tumescent torrent into the vast magisterial piazza, the true marvel of the modern universe. I remember finally so many singers, players, and dancers all jumbled together, the endless charlatans, mountebanks, storytellers, and crooks that covered the piazza and the so-called Riva degli Schiavoni, and the inns crammed with foreigners and their banquets, feasts, and parties—in sum, an ordered disorder that delighted with the most surprising chaos of sport and merriment that nevertheless harmed no one and made the carnival of Venice the first and most pleasing carnival of our mad hemisphere.

The writing is deft, discrediting the event without denying locals their remembered pleasures. A malign air of sexual disease hovers over the account. “To the consequent moral breakdown was added every physical corruption and misery, first convulsing and then destroying the delicious happiness now lost.”9 The city had tolerated its despots by chasing after mad pleasures, willingly distracted and oblivious to the decay.

Exceptions were eventually made to the decree banning masks, but only for the highly decent and closely monitored masquerade balls at the Fenice and San Benedetto theaters. Nearly twenty years after the decree, the press was defending it in vaguely patronizing terms. “It follows that after such an extended and dangerous illness—and even in its continuing convalescence—the patient cannot in full but only in part resume its habits.”10 The Ridotto, which had been closed for nearly seventy-five years, underwent substantial renovation to reopen in 1816 as a model of decorum. New lighting eliminated its dark recesses; marble columns shimmered in the new central hall; there was a restaurant for diners, a salon for conversation, and a large area for dancing. That year, it hosted seven balls in January and eight in February. High ticket prices insured that the participants were respectable. There were no reports of disorder.

Eventually the Austrians permitted popular carnival celebrations to resume, but they were policed to such a suffocating degree that the civic spirit known before the fall never returned. In its place was a weaker version, vapid, commercial, and staged primarily for wealthy tourists. Official accounts of carnival wear a forced smile for most of the nineteenth century, as bearded Austrians in top hats and greatcoats took the places of Venetians in mantles, masks, and tricorns. The descriptions conclude predictably. The population is happy, the festivities are at last decent, gratitude reigns.

Such is the history written by those who win wars.

Giandomenico Tiepolo offered an alternate eulogy for the mask that was not triumphant. His dark farewell to the Republic came in a collection of pen-and-wash drawings he called Amusements for Children. Despite the title, Divertimenti per li regazzi is neither simple nor innocent. The 104 images that make up the set depict a race of Pulcinellas living among ordinary Venetians. Their lives look much like those of other Venetians. They fall in love, marry, and raise children; they work as carpenters, tailors, barbers, and schoolteachers; they sing, drink, dance, and die. Some deaths are not ordinary. Two are executed, one by hanging and the other by firing squad.11

Amusements for Children is the offspring of national collapse and personal withdrawal. It is also the unique product of a culture in which masking was widespread and not always festive. The masks of these Pulcinellas do not disguise or deceive. Their baggy blouses and trousers are not costumes. The strangeness of Venetian masking in the eighteenth century—its haunting blankness, its absurd coupling of hilarity with solemnity, its self-replicating uniformity—is captured in these drawings. In Divertimenti per li regazzi, Tiepolo extends the mask to all moments, public as well as private. Pulcinellas come into the world, go about their business, and are laid in the grave with their faces half covered.

Pulcinella was the one character of commedia dell’arte not to conform to a prescribed repertoire of roles. Some have supposed that Tiepolo chose the figure to stand as an Everyman in Amusements—“our Doppelgänger, our mirror or surrogate,” as one art historian puts it.12 In the collection, Pulcinellas are varied in the extreme. They populate all reaches of the social scale as masters and apprentices, schoolteachers and pupils, lords and tenant farmers, executioners and their victims. If Pulcinella is an Everyman, his pleasures and pursuits identify him as Venetian. Tiepolo’s integration of this curious breed into the affairs of the city creates an uncanny sense of familiarity, as though commedia characters have finally managed to free themselves of the stage and are at last living as they wish. Like Goldoni, Tiepolo made these characters fully human, but in Amusements for Children he found a way to do so that was also faithful to the public face of this city of masks. In retaining their masks, Tiepolo sacrifices none of his subjects’ dignity, individuality, or expression.

Tiepolo’s Pulcinellas are likewise freed from commedia’s degradations. They are passionate in love and high-spirited in play. They prepare meals with gusto and relish eating. They drink wine, doze, quarrel, and brawl. When they have to, they urinate or defecate by the roadside. They are not drunks, lechers, clowns, half-wits, or gluttons. They are not insolent, vulgar, or brazen, and there are no obvious displays of disobedience to authority. There is nothing demonic, or even particularly disruptive, about their masks or antics. A carnival scene, for instance, has two Pulcinellas on donkeys and a clutch of others dancing with banners and musical instruments. The mood is jubilant rather than raucous.

Their joy is full-throated and abundant. They link hands to dance with peasants in the country, clapping, prancing, playing pipes and tambourines. In a badminton match their glee is childlike; they carry the winner on their shoulders in triumph. They marvel at the circus, and at the leopard’s cage several speak at once, comparing observations (figure 31). The images draw a smile, but the humor is not easy to classify. There are few jokes at the Pulcinellas’ expense, and they do not pull pranks on one another. Although distorted by hunchbacks and bulging bellies, the figures are not exactly caricatures. The exaggerations do not mock or deride. The public scenes lack Hogarth’s scathing satire. Those with violence are far from the savagery of Goya. The elegance conveyed—in Pulcinella’s wedding procession, for instance, or when Pulcinella escorts a masked woman—lacks Watteau’s charm. A deliberate lumpiness in the images works against enchantment or sensuous delight. The line is tremulous, the shading splotchy.

FIGURE 31. Giandomenico Tiepolo, At the Leopard’s Cage (no. 38)

Yet Tiepolo’s mastery of bodily expression communicates human pathos, tenderness, and joy in situations that would otherwise be absurd. The effect both attracts and perplexes. A mother peers with wonder into the eyes of her baby-Pulcinella, masked and in swaddling clothes, who stares back intently at her (figure 32). Her Pulcinella-husband rests a protective arm across the chair and leans toward a visitor with pride and a little defiance. Only the dog is excluded from the group’s interlocking gazes. Judging by his expression, he has already grasped what this means for him. (Hangdog in Italian is cane bastonato, “whipped pup.”) Late in the series, Pulcinellas work awkwardly to lower a dead companion into the pavement (figure 33). The rump of one looms up; another twists his torso and braces a foot to keep his balance. Three onlookers show more fascination with the maneuver than sorrow. A young Pulcinella off to the left—is he a son of the deceased?—has lost his hat in his grief.

FIGURE 32. Pulcinella Swaddled in His Crib (no. 10)

An undertone of melancholy runs through Amusements and is present even in the happy scenes. The overall mood is elegiac, a late-work sense of leave-taking compounded by cultural loss. As one of the subtlest commentators on Tiepolo has written, the collection is “the disenchanted testimony of a dying society unaware of its own end.”13 Yet its moments of anguish occur as if at a remove, lightened as they are by the masks and attire. A Pulcinella has collapsed on a country road and others now gather to comfort him. Pulcinella’s sick lover vomits into a bedpan that he awkwardly holds for her. A dying Pulcinella, his hooked nose pointing toward heaven, receives the last rites. The Pulcinellas live with immediacy and ardor, now dancing, now weeping, now flaring up in anger. Their delight is both ours and not ours. Their pain is real although felt from a distance. The late Philipp P. Fehl, an artist and author who fled Vienna as storm troopers swept the city for Jews, found both sweetness and terror in these drawings. For him, they exhibit “the most significant use of poetry: the consolation it affords us by taking the measure of true things bravely, and with a wink.”14

FIGURE 33. Burial of Pulcinella (no. 103)

Tiepolo was seventy years old and living at the family’s mainland villa when the Republic collapsed. His father, Giambattista, had died in 1770. For most of his professional career, Domenico had worked in the shadow of the elder Tiepolo, whose glorious rococo frescoes of saints and the holy family direct the eye upward: to pink-orange clouds, angels rocketing to heaven, martyrs clothed in blazing whites and silvers, and serenely imperious Madonnas. Domenico’s works are mostly earthbound. His Mary and Joseph make their dusty way to Egypt. His saints endure agony. His Stations of the Cross, painted for the Oratory of the Crucifix in Venice’s Campo San Polo when he was twenty-one years old, are emotionally raw. Christ stumbles through crowds of the beseeching and the indifferent. Lining the way are despots in their robes and turbans, brutish soldiers, affluent children, and Domenico’s own plausible contemporaries, who look back at us helplessly from inside the frame. In Domenico’s work, cruelty, ugliness, and banality defy—and at times sully—the pure. St. Stephen is martyred not by stones but by boulders dropped from above. A soldier braces a foot against Christ’s leg to whip him. A bored dog stares off into the distance as Mary cradles her dead son.

FIGURE 34. Birth of Pulcinella (no. 1)

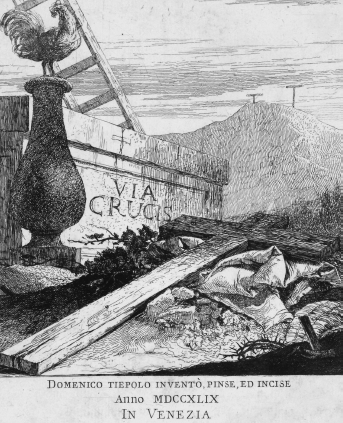

In retirement, Domenico spent his days covering the interior walls of his villa with frescoes. Pulcinella is present in most of them, frolicking with a lover, strolling with country-folk, bunched in a tight group to watch acrobats leap and tumble. On the ceiling of a small interior room, a happy Pulcinella on a swing thrusts himself into the skies. Amusements for Children was drawn in this villa. Tiepolo likely began it sometime after the Republic’s fall in 1797. It is not known when he finished the drawings or what his intentions for them were. In 1921, the set was shown publicly for the first time at an exhibit in Paris sponsored by Sotheby’s. It was photographed and then auctioned off, print by print. Seventy-seven drawings survive in private and public collections; the other twenty-seven are unaccounted for. Although Tiepolo numbered the pages, the order defies any clear narration. The images are untitled. In the first drawing, Pulcinella is born in a stable from a turkey egg (figure 34).15 A wedding follows, and a wedding feast. Then comes a courtship, and after that an infant. Is this the jumbled biography of an individual, or are we witnessing key moments from the lives of many Pulcinellas? The set’s frontispiece is mysterious. A marble monument set in a forlorn landscape bears the title, Divertimenti per li regazzi (figure 35). Before it stands a solitary Pulcinella clutching a doll that seems more alive than he. The monument could be a stage, or an altar, or a tomb. Is this an introduction to these lives or a desolate conclusion?

FIGURE 35. Frontispiece, Divertimenti per li regazzi

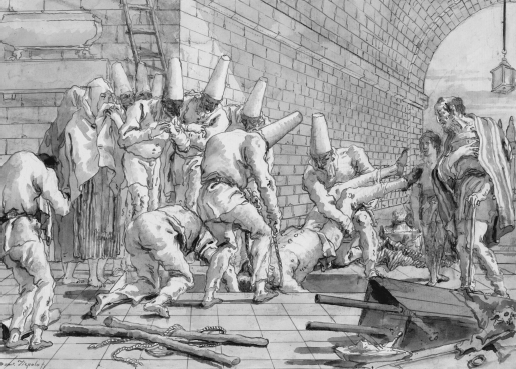

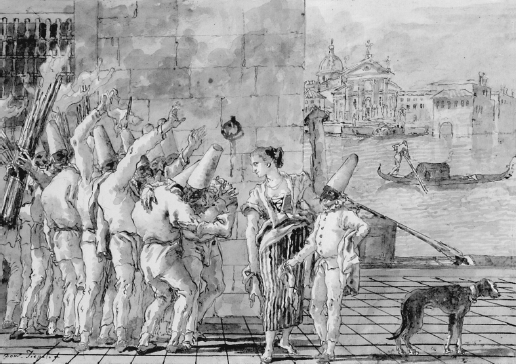

Read against the grim backdrop of events in Venice, the drawings reveal details rich in meaning. A third of the way into the set (no. 33), Pulcinella is taken into custody by officials wearing bicorn hats, headgear favored by the French as opposed to the tricorn, which Venetians preferred (figure 36). An unnumbered image (likely no. 34) shows Pulcinella in prison (figure 37). He holds a despairing hand to his head as a hooded woman speaks to him through the bars and a throng crosses the bridge before him. The busy action, which includes peddlers, women bending over a basket, a strapping lad with a pail on his head, and two idle or impatient Pulcinellas at the top of the bridge, distracts from what’s happening in the far left. A local boy is trying to pickpocket a man in a bicorn.

No. 35 shows Pulcinella before a three-man tribunal (figure 38). A secretary reads an edict granting pardon as a jailer removes Pulcinella’s shackles. One judge is fiercely resolute, a second registers disapproval, and a third shows sudden confusion or fear. The same hooded woman who appeared at prison and four Pulcinellas stand before the tribunal in bowed supplication, their cone hats deferentially removed. The next drawing (no. 36) suggests exile, as Pulcinella is embraced by a band of brethren on the quay before the prisons of the ducal palace (figure 39). Perhaps the four drawings are politically insignificant. This Pulcinella may be a thief or troublemaker. But no earlier crime is depicted. And what sort of regime arrests and imprisons a troublemaker only to pardon him grandly and send him into exile? One answer would be a regime intending to intimidate. The sequence evokes the fate of Nicolò Morosini, the former officer exiled for having criticized the Municipality.

FIGURE 36. Pulcinella Arrested (no. 33)

FIGURE 37. Pulcinella in Prison (no. 34?)

FIGURE 38. Pulcinella before the Tribunal (no. 35)

FIGURE 39. Pulcinella’s Farewell to Venice (no. 36)

FIGURE 40. At the Lion’s Cage (no. 39)

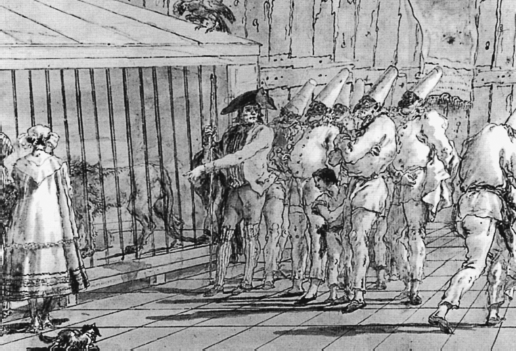

No. 39 in the series, which immediately follows the visit to the leopard’s cage, shows another group of Pulcinellas studying an animal, now in considerably different postures. Here an official in a bicorn and holding a pike points to a caged lion (figure 40). Its head is not visible, but its body looks scrawny and beaten down. A bird of prey waits above. The sentiments of six Pulcinellas are difficult to read. They are close-lipped, arguably distrustful or defiant, largely expressionless. A seventh turns out of the frame in what looks to be sudden grief. His posture is virtually identical to that of the boy who weeps as Pulcinella is lowered beneath the pavement in figure 33. The lion was famously the symbol of Venice. In the presence of occupiers, most locals would want to hide their thoughts or, if overcome with emotion, turn quickly away.

FIGURE 41. Pulcinellas Bring Down a Tree (no. 40)

If the drawings beginning with no. 33 form a sequence, then the next two are defiant. In no. 40, a scene in the countryside, Pulcinellas bring down a tree as others lift their arms in triumph (figure 41). To the left stand two onlookers, one with a conquering foot on a bundle of sticks that resemble the iconic fasces of the French Revolution. An ax typically enwrapped in the cluster announced the terror of swift justice. Here a woodsman holds the ax. The symbols prompt a political reading: crowds cheer as Pulcinellas pull down a Liberty Tree and dismantle fasces.

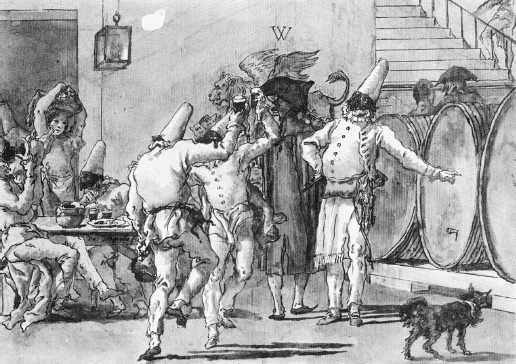

The next image (no. 41) is a spirited scene in a tavern, where two Pulcinellas kick up their heels with drinks in their hands (figure 42). The same shirtless lad who crossed the bridge in front of the prison is here, still bearing a load on his head. On the back wall Tiepolo has drawn a robust lion of St. Mark’s under two overlapping Vs. That piece of graffiti, then as now, sounds a cheer: Evviva! Together with the lion, it forms a rebus of the outlawed salute Viva San Marco! An earlier work by Tiepolo gives evidence of the artist’s changing intentions. It contains a substantially similar scene without the Pulcinella masks and clothes (figure 43). A single dancer hoists a glass in a tavern, with drinkers at a table to the left and a cellarer and casks on his right. A lion is pictured obscurely in the rear, near the steps. Moving the animal to the center and crowning it with double Vs turns the dance into a toast.

FIGURE 42. Tavern Scene (no. 41)

Domenico Tiepolo filled Amusements for Children with allusions to other artworks. One needn’t identify them to sense incongruity: in the observing presence of turbaned foreigners, alone or in pairs; in the man and child who attend Pulcinella’s burial in the pavement of Venice as if from another time; in a curious pair of miniatures before Pulcinella and his masked escort, as though Rembrandt’s Blue Boy has come to life alongside one of Goya’s majas. Near- or direct quotations add a cryptic layer to these drawings. The mother-and-son scene with Pulcinella in swaddling clothes resembles Giovanni Bellini’s Presentation at the Temple (itself inspired by a painting of Andrea Mantegna). A wedding banquet of Pulcinellas restages Veronese’s Wedding at Cana. A farmer-Pulcinella shovels earth in the exact pose of a worker digging a hole for a thief’s cross in Jacopo Tintoretto’s vast Crucifixion.16

FIGURE 43. Tavern Scene, 1791

FIGURE 44. Execution by Firing Squad (no. 97)

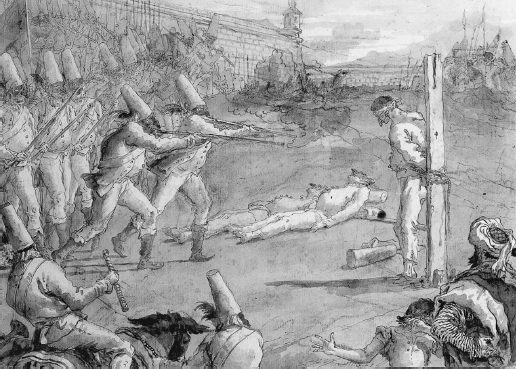

FIGURE 45. Jacques Callot, The Firing Squad

The two executions, both rich with allusion, come late in the series. The first is closely modeled on a scene from Jacques Callot’s Miseries of War (1633). A blindfolded victim stands bound to a post with a heap of bodies off to one side as his executioners step into formation (figure 44). Tiepolo’s modifications are worth noting. In the Callot print, the shot has just gone off (figure 45). We see a burst of smoke; a dog’s tail stiffens in sudden interest. Tiepolo, by contrast, captures the instant before the shot. He replaces Callot’s billowing plumes on the soldiers’ hats with jagged feathers resembling a (Gallic?) rooster’s tail. Tiepolo would have known about the execution of the Venetians Marinato and Panadella by a French firing squad in late December 1797, just two weeks before troops ceded authority to Austria.

In the second execution, a lifeless Pulcinella hangs from a noose (figure 46). A heavy mustache distinguishes the commanding officer, whose headgear has no rooster’s tail. Near the foot of the gallows, amidst a mass of Pulcinellas, stands a boy who looks out of place in his glistening, square-shouldered doublet. His ears tilt outward. This boy is also present in Tiepolo’s Stations of the Cross, seen from the back and gazing up as his mother speaks to Christ (figure 47). In Tiepolo’s Execution by Firing Squad, a girl in the foreground hides her face and splays her fingers in horror. That same hand, with its thumb bent back and a wedge of shadow in the palm, rises above the heads of onlookers in his Stations of the Cross as Christ falls (figure 48).

The matches are not exact and are perhaps unintentional. But there are other echoes in the Pulcinella scenes from Tiepolo’s depictions of Christ that should be considered before discounting such similarities. The turbaned foreigners who appear on the road to Calvary are also witness to the two executions and other key moments in Pulcinella’s life. The stance, hood, and turban of an observer outside the grate of Pulcinella’s prison cell are virtually identical to Tiepolo’s engraving of the seventh Station of the Cross, a reverse image of the painting (figure 49). The turbaned men are also present when Pulcinella is lifted high in triumph, taken into custody, whipped, and, after his death, viewed by mourners, a narrative (which necessarily omits and conflates) that retells the life and death of Christ from his entry into Jerusalem (figure 50). If Tiepolo meant Amusements for Children to carry intimations of divine sacrifice, this is how he would have accomplished it.

FIGURE 46. Death by Hanging (no. 98)

The frontispiece to Amusements for Children shares features with the engraved frontispiece to Tiepolo’s Stations of the Cross done fifty years earlier. In the latter, a tomblike monument bearing the title is also set in a desolate landscape (figure 51).17 Their attributes are of course different—in one, a toppled hat and discarded jacket, wine, and a plate of gnocchi; in the other, the cross, a rumpled cloak, the crown of thorns, and a hammer—but both bear powerful witness to an absence. In one, it is the possessor of the jacket and hat. In the other, it is the man who wore the cloak and crown of thorns.18 Both contain ladders, one made of planks and the other of rounded beams. The flat-planked ladder leans against the cross in Tiepolo’s Stations to retrieve the body of Christ. The round-beamed ladder rests against the gallows in his Death by Hanging to cut Pulcinella down. It is also in the stable where, like Christ, Pulcinella was born (see figure 34, above).

FIGURE 47. Station 8 from Stations of the Cross

FIGURE 48. Station 9 from Stations of the Cross

In the late eighteenth century, a French traveler to Venice wrote that Pulcinellas proliferated in the city. He encountered them on the stage and in other entertainments, in paintings and literature, and especially among revelers during carnival. The procurator Marco Foscarini disapproved of these costumers’ crude talk and weighed banning all Pulcinellas from Piazza San Marco. Pulcinella was also a favorite puppet in the city. In the 1770s, a government agent reported that children were imitating his vile language.19

In the urban dreamscape of Amusements for Children, Pulcinella also proliferates, but here he is far from the vulgar clowns these contemporaries knew. Tiepolo humanized Pulcinella by integrating him into civic life and the attachments of family. This humanity brings a solemn, local cast to Pulcinella’s sufferings and especially to his death, whose intimations of sacrifice lead us away from the irreverent flood of puppets and revelers. The closer affinity lies with the “true Pulcinella” Diderot had reported in Piazza San Marco, where a Venetian priest lifted a crucifix in the midst of charlatans’ stages.20

FIGURE 49. Station 7 from Stations of the Cross

FIGURE 50. Scourging of Pulcinella (no. 85)

FIGURE 51. Frontispiece, Stations of the Cross

By conferring political and religious associations on a Venetian Everyman, Tiepolo cast the fall of the Republic as tragedy. This was in keeping with the ritual violence that marked the coming of spring every year in and around Venice. Tiepolo probably knew that among those ritually killed were effigies of Pulcinella. But there is one crucial difference that separates the recurring seasonal violence and the Republic’s immolation, which Tiepolo also understood. The demise of this carnival-city carried no redemption. This death of carnival, Lent without end, brought bitter ash.

The last image in Amusements for Children is horrific. Pulcinellas have come to a tomb in what appears to be morning light as a skeleton bursts hideously from the grave (figure 52). The decaying remains of another Pulcinella lie unburied. The living recoil in sudden fright, their arms raised in a tangle. The skeleton is in midair. His head turns back, but his toes have already begun to flatten against the ground. In a moment he will crash forward in a heap, his bones clattering across the rotting torso. There will be no resurrection.

FIGURE 52. Pulcinella’s Tomb (no. 104)