We stood outside the station, bags at our feet, and waited for the carriage to come and whisk us away to Butterfield Park. I’m usually an excellent waiter. I once waited for a miracle. It took seven and a half weeks. Yet I never gave up.

But right now I was tired. And it was getting late.

“Lady Amelia didn’t say she would send a carriage in her letter,” I said, swatting away an insufferable moth. “I just assumed on account of me being a welcomed guest. . . .”

“Don’t be shocked, Ivy,” said Rebecca, still gazing with alarming fondness at the mysterious box in her hands. “I’m sure my aunt meant to send the carriage, but it’s easy to be forgotten at Butterfield Park—unless your name happens to be Matilda.”

“Do you have any more cake, dear? I’m positively starving.”

“You ate the last piece twenty minutes ago.” Rebecca sighed. “We’ll have to go on foot. I hope you’re a good walker, Ivy.”

“Stupendous,” I said, picking up my bag. “When I was four, I walked across India with my father. He wanted to paint ashrams and elephants and whatnot. I hardly broke a sweat.”

Rebecca frowned. “You’re lying.”

“Who can say?” I pointed at the suitcase. “Shall we get started?”

We mounted the crest of a small hill and headed down an avenue bordered by elm trees, through which Butterfield Park was revealed in all its glory. It was a fine building with marble columns and magnificent turrets and chimneys reaching towards the heavens. A clock tower crowned the east wing. Surrounding the main house was a tapestry of formal gardens full of roses and tulips, a wildflower meadow, an apple orchard, and a pretty summerhouse. The entire estate was circled by woodlands.

“It’s perfectly lovely,” I declared.

“Wickam took care of the gardens,” said Rebecca softly. “He loved them so. I think he was the only person around here Grandmother actually liked—well, apart from Matilda.”

“Has he been gone long?”

“He died last winter. We have a new gardener now.” Rebecca scratched her nose. “He’s young and clever and full of new ideas for the wildflower meadow. Everybody hates him.”

“Quite right too,” I said.

Rebecca giggled.

We ambled up the gravel drive. “They are probably still packing up from the theatrical last night,” Rebecca said glumly. “My aunt fancies herself a writer. She loves to put on plays and recitals.” She must have noticed the ravishing smile upon my face because she said, “Do you act, Ivy?”

“Brilliantly,” I said. “I toured America in a production of The Secret Garden. I played Mary Lennox, of course. The critics raved about me. Said I lit up the stage like a mid-sized house fire.”

Rebecca was frowning. “You did no such thing.”

“Of course I did.” I shrugged. “I’m practically positive.”

We reached the large oak doors and were ushered into a great hall. I spun around, taking in my surroundings. The hall had dark paneled walls, a massive carved staircase, a large coat of arms above a marble fireplace, and a stupendous chandelier suspended from the vaulted ceiling. Rebecca told me the house had more than ninety rooms. A west wing and east wing. Servants’ quarters. A majestic library. Staircases everywhere you looked. Banks of stained-glass windows. More hallways and corridors than a hospital.

“Where is my aunt?” Rebecca asked the butler.

“She’s in the library, waiting for little Miss Pocket,” came a voice from behind us.

“Blast!” hissed Rebecca. She pushed her mysterious box into my arms. “Pretend it’s yours,” she whispered. “Please.”

Of course I played along—for I have all the natural instincts of a professional trickster. I turned and was rewarded with my first glimpse of Matilda Butterfield. She was a contrast to her fair cousin—dark hair, hazel eyes, the reddest lips I’d ever seen, and an olive complexion. She looked like a doll. Lovely, but somehow unreal.

Rebecca introduced us and we exchanged a polite greeting, but the whole time Matilda’s eyes were fixed on the package I was holding.

“Is that it?” she said eagerly. “Is that my diamond?”

I looked down. “This? Of course not, dear.”

“Then what is it?” asked Matilda.

Rebecca gulped and looked at me with pleading eyes. I had no idea what was going on. But I knew she needed me. “Nothing,” I said. “Just something I picked up in London.”

Matilda smiled coolly. “Is it nothing or something?” she said. “You seem confused, Pocket.”

I sighed. “It is really rather personal, dear. My aunt Agnes is a fruitcake. Barking mad. She’s been locked away for years on account of her blowing up Mrs. Digby’s prize-winning dairy cow. Naturally, Aunt Agnes spends most of her time in a straitjacket. But once a week, for one precious hour, she is freed from her restraints. And in that one hour, my insane aunt likes to bake. Cupcakes. She’s very talented.” I looked down at the box with suitable affection. “I receive a package like this every week, containing a single vanilla cream cupcake. It’s really very sweet, don’t you think?”

Matilda Butterfield didn’t say anything at first, her eyes moving back and forth between Rebecca and me. At last she said, “Can I try it?”

“Try what, dear?” I said.

“Your insane aunt’s cupcake, of course,” said Matilda, flicking her dark locks.

Before I could answer, she snatched the box from my grasp. Then she did the strangest thing—she put the box up to her ear. I looked to Rebecca, but she just groaned wearily and stared at her feet.

“I knew it!” Matilda declared. “You’ve done it again, haven’t you, cousin?”

“Done what?” I asked.

Now it was Rebecca’s turn to snatch the box away. “Mind your own business!” she hissed. Then she hurried away, practically running up the staircase.

I looked back to Matilda for some sort of explanation.

“Come on, Pocket,” she said, turning on her heel and striding from the hall. “My grandmother wants to see you.”

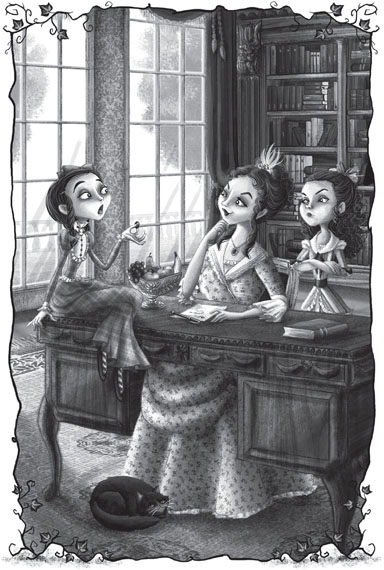

“Where is Rebecca?” That was Lady Amelia’s first question after I set down my carpetbag and introduced myself with a breathtaking curtsy.

“She’s gone to her room, Mother,” said Matilda sweetly. “Same as always.”

Lady Amelia was a regal and slightly pudgy creature, in a yellow gown of the finest silk, perched before a writing table, a black cat at her feet. She had Matilda’s dark hair and features (apparently she descended from Italian royalty).

“Did she . . . did she do it again?” she asked, looking anxiously at Matilda.

“I’m afraid so, Mother.”

“I don’t know what to do,” said Lady Amelia wearily. “We have tried everything to make her stop—but she will not.”

I could only assume they were referring to the mysterious box. Now, while I had no idea what that was about, I was certain I could help. “Forgive me, Lady Amelia,” I said, pushing a bowl of grapes out of the way and sitting down on the edge of her writing table, “but I got to know Rebecca rather well on our train journey from London. It’s clear the poor girl is unhappy. Why is she unhappy? Well, I can’t say for sure, but I’m almost certain it’s all your fault. Not just you, dear. The whole family.”

Lady Amelia was smiling now (strange woman). “I see. Go on . . .”

I jumped off the writing table and plucked a grape from the bowl. “Well, if melancholia is her problem, I have an excellent remedy. All I need is a glass of cranberry juice and a hammer. It’s remarkably effective.”

Lady Amelia’s laugh was rather musical. Why she was laughing, I hadn’t a clue.

“She’s mental,” said Matilda with a huff. “She makes no sense at all.”

I was outraged that she was talking about her cousin in that way. It was very rude. But before I could slap some sense into her, Rebecca appeared in the doorway. Rather sheepishly, she entered the library.

“Welcome home, Rebecca,” said Lady Amelia. “Was London a success?”

“If you mean did I get fitted for the dress, the answer is yes,” said Rebecca.

Lady Amelia regarded her niece carefully. “And did you keep your promise?”

Rebecca immediately looked at Matilda, who was smiling wickedly.

“Of course she didn’t keep her promise,” came a brittle voice from somewhere across the room. I turned but could see no one. That corner of the library overlooked the rose garden, and in front of the windows stood a single winged back chair. An elderly woman dressed all in black began to rise up from behind it. She moved slowly, with the aid of a cane.

“Foolish girl,” she hissed at Rebecca.

“Lady Elizabeth, do not be too harsh,” said Lady Amelia. “I am sure Rebecca tried her very hardest. This is a complicated matter.”

“Claptrap!” spat the old geezer. “She must stop, and she will. Or else. Is it any wonder I will not make her my heir?”

Lady Elizabeth was not at all what I had expected. While she spoke with all the regality of Queen Victoria, she had a head like a walnut. Hands like claws. A body withered and thin as a rake. Her skin had seen more bad weather than a lighthouse. She was also rather mean.

Rebecca mumbled something about being sorry and promising to try harder and whatnot. I was on the point of asking for a snack when Lady Elizabeth turned her wrinkled gaze on me.

“Where is the necklace?” she said coldly. “That is why you are in this house, is it not?”

“The diamond is somewhere safe,” I said, smiling at the old woman. “Now be a dear, and fetch me a dozen uncooked potatoes.”

“Fetch you what?” she barked.

“You must be famished after your journey, Ivy,” said Lady Amelia, hastily ringing the bell.

“Starving,” I said. “Haven’t eaten in days.”

“The necklace, Miss Pocket,” said old Walnut Head, eyeing me fiercely. “Bring it here this instant!”

“Not possible, dear,” I said, shaking my head. “The Duchess of Trinity gave me very strict instructions about the Clock Diamond. No one can see it until the birthday ball.”

Just then, a pale woman with startling red hair pulled back in a tight bun entered the library.

“Please excuse the interruption,” she said crisply. The poor creature had an accent. American, I think. “I am after a book of French poetry for my next lesson.”

“Where are the smelling salts?” muttered Matilda. “I won’t survive another of her dreary lessons!”

“Matilda, what an awful thing to say,” whispered Lady Amelia. “Miss Frost has only been here a few days. You must give your new governess a chance.”

Miss Frost hurried over to the shelves by the spiral stairs and busied herself sorting through the books. All the while, she kept stealing glances at me. There was something vaguely familiar about her, but I couldn’t think what. Which was odd.

“I demand you show me the diamond, Pocket,” snarled Matilda. “I have a right to see it! How else can I be certain it will complement my dress for the birthday ball?”

“Fear not, Matilda,” I said brightly. “You are blessed with such a naturally weather-beaten complexion, I am certain the necklace will do wonders for your appearance.”

A bitter smile creased the awful girl’s face as she glared at me. “I pity you, Pocket. You’ll never know what it’s like to wear a priceless jewel. To have every girl in England just wishing she was you.”

“Don’t be so sure,” I said, unable to help myself. “Not the part about having every girl in England wishing she was me, of course. Although I was voted Girl Most Likely to Burn at the Stake two years running. But as for the Clock Diamond—I hate to burst your balloon, dear, but I’ve already worn it, and I looked heartbreakingly pretty.”

A loud bang echoed through the great library. All eyes snapped to Miss Frost, whose book had tumbled to the floor. She looked frightfully pale as she bent down to pick it up.

“You had no right to wear what doesn’t belong to you,” bellowed Matilda.

“The Duchess of Trinity said that I could,” I told her, feeling the moment was right for some serious lying. “In fact, that dear, sweet, potbellied dingbat positively insisted. She was very particular when it came to the Clock Diamond.”

“I am rather stunned that she wished to give Matilda such a valuable gift,” said Lady Elizabeth shrewdly. “We were not exactly friends these past sixty years. It is most unexpected.”

I retrieved the Duchess’s letter from my bag and handed it to Lady Elizabeth. “I have a feeling she wished to make peace with you.”

“Hush,” snapped Walnut Head. She read the note, and I saw the fire in her eyes dim just slightly. She muttered softly, “Well, well, old friend . . .”

“It’s just so tragic,” said Lady Amelia gravely, “what happened to the Duchess.”

Matilda’s face clouded over. “I’m not sure I want a necklace from a dead woman.”

“Claptrap!” barked Lady Elizabeth. “The Duchess was rich and friendless, it’s no wonder someone put a knife in her chest.”

“Do you have any idea who killed her, Miss Pocket?” said Miss Frost rather suddenly. She had the book of poetry open in front of her. “She was murdered very soon after giving you the necklace, was she not?”

“Yes, dear,” I said. “The whole business is terribly mysterious. Lunatics left, right, and center. And as the Duchess’s messenger, I feel a great sense of responsibility to her memory.” I sighed mournfully. “I was the last person to see her alive.”

Miss Frost slammed the book shut. “I would imagine the killer was the last person to see her alive.”

Then she excused herself and stalked from the library.

“Well, I don’t think it’s fair,” muttered Matilda, throwing a cushion at the cat. “Why should I have to wait until my birthday to get the necklace? That’s not for five whole days!”

“That is not the worst part,” said her grandmother. “We are to be stuck with Miss Pocket for five whole days.” She looked at me hopefully. “Unless you have somewhere else to be?”

“Heavens no,” I said. “I’m soon to come into a fortune. Until then, I’m free as a bird.”

Rebecca picked up my carpetbag and said, “Ivy must be exhausted, and I’m sure she wishes to freshen up. I’ll show her up to the guest bedroom.”

Which was thrilling.

“Certainly not!” cried old Walnut Head in outrage. “Put her in the attic. Miss Pocket may be our guest, but she is not one of us. She is a maid, and maids do not sleep in guest bedrooms.”

And with that, she turned her back and returned to her chair by the window.

Beastly bag of bones!

The attic was tucked away in the east wing—up the main stairs, across a landing, down a long hallway, and up three more flights of rickety back stairs. Finally I was led into a dimly lit corridor. Frightfully narrow. A door on either side. I was informed that the narrow staircase at the far end led up to the roof.

My bedroom was plain. Wood floors. Sloping ceilings. Whitewashed walls. Jug and basin. Little window overlooking the schoolhouse. Which was a blessing. I had no tolerance for comfy chairs, pretty curtains, or comfortable beds. The room across the hall was apparently a dusty chamber used to store the costumes and props from Lady Amelia’s theatricals. So I was quite alone.

I washed my face, changed my dress, and went to explore the house. But not before sewing the Clock Diamond into the pocket of my new dress. I felt it was probably best that I kept the stone with me at all times.

I stood at the banister of the first-floor landing and looked down—a maid or two hurried past, carrying brooms and mops. Then my eyes were drawn by the radiant chandelier suspended above the great hall. Could that be just the place to hide the necklace? If only I had a ladder.

Footsteps clicked rapidly down the hall to my left. I heard a door open. Being naturally curious, I tilted my head and peered down the vast corridor—just as a girl slipped into a doorway at the far end. The door shut quietly. I thought it was Rebecca.

Only one way to find out.

“Rebecca?” I knocked gently on the door.

Nothing.

“Anybody there?”

I heard movement on the other side. Shuffling of feet.

The door opened. Just a crack.

“Yes?” It was Rebecca. She looked guilty. Or scared. Or something.

“Is this your bedroom, dear?” I asked.

She nodded. It was clear she had no intention of inviting me in.

“I have a dreadful problem,” I said. “As you know, I’m soon to have five hundred pounds. Which means I will need to smarten up my bedroom. And I was very much hoping you would let me see yours, dear. You know, as inspiration and whatnot.”

“It’s awfully messy, Ivy,” she said. “Perhaps some other time.”

“Oh, don’t worry about the mess,” I said brightly, putting my hand on the door and pushing just a little. Well, I tried to. Rebecca had her foot wedged against the other side. “If you like, I’ll help you clean up. I’m an excellent duster.”

Rebecca shook her head. Then she opened the door just enough to squeeze herself through and slipped out into the corridor. The door closed behind her before I could catch more than a glimpse inside. She then took a key—threaded on a ribbon around her wrist—and locked the door. Which I thought was rather excessive.

“It’s such a lovely afternoon,” she said. “Why don’t I take you outside and show you the schoolhouse? It used to be Lady Elizabeth’s summerhouse, but now it’s where Matilda and I have our lessons. It’s really very pretty.”

Before I had a chance to protest, Rebecca led me quickly down the hallway.

We made our way along a path beside a blooming avenue of yellow tulips, which led directly to the schoolhouse. The building was white, with a thatched roof and lattice windows. Terribly fetching. Miss Frost passed us, carrying a large dictionary and hurrying towards the schoolhouse. She stopped and directed her attention to Rebecca.

“Class commences in ten minutes,” she said crisply. “You have completed your book report?”

“It is nearly done, Miss Frost,” said Rebecca rather meekly. “If you will just give me a little more time . . .”

“Oh, Rebecca,” said Miss Frost with a sigh. “You have only been my pupil for a few days, and already you are behind. I am certain you are a bright girl with great potential, but I cannot think what you do all day, locked up in your room.” Miss Frost’s gaze softened. “Will you promise to try harder?”

“Yes, Miss Frost,” came the faint reply.

“It’s my fault, dear,” I said, giving Miss Frost a congenial slap on the arm. “Rebecca was hunched over her report when I found her. I practically begged her to show me the gardens. I cried. Hit my head against the wall. All sorts of madness. So you see, it’s really my fault, not hers.”

To my surprise, Miss Frost didn’t bite my head off. In fact, her freckled frown faded and she laughed lightly. “You have a way with words, Miss Pocket. I don’t know that I believe any of it, but it is most entertaining.”

I huffed. The nerve!

Miss Frost looked back at Rebecca. “You have eight minutes to finish your report,” she said, pointing to the schoolhouse. “I suggest you hurry along.”

“Yes, Miss Frost,” said Rebecca, making a hasty retreat.

When we were alone, Miss Frost quickly turned her attention to more serious matters.

“I have no business saying this,” she said, her eyes falling intently onto mine, “but I am worried, Miss Pocket.”

“What about?” I said.

“The diamond. I read a great deal—it is rather a habit of mine—and I have learned something of the Clock Diamond’s history. It is dark, indeed. Have you . . . has there been any trouble since the stone came into your care?”

“Not really,” I said brightly. “The odd break-in and whatnot. A darling old lawyer in London thinks differently—he sees danger around every corner—but I have kept the necklace perfectly safe.”

“I have heard there is a vault here at the house,” said Miss Frost. “I am sure Lady Elizabeth would let you keep the diamond there until Matilda’s birthday.” She patted down her dazzling red hair. “It is just a thought.”

“There’s no need for that,” I said. “I keep the stone with me at all times.”

“That is very unwise,” declared Miss Frost, her face hardening. “In the last few weeks there have been several brazen robberies in the county. Lady Francesca’s daughter was hit in the head and had her gold watch stolen as she walked home from church. Furthermore, people in possession of the Clock Diamond have a habit of dying rather violently. You would do well to remember that.”

I sighed. “I suppose you think the diamond is cursed?”

“There is no such thing as a curse,” said Miss Frost tersely. “Where the Clock Diamond originated, no one knows. Few people have even laid eyes on it. But I have read that once they do, they find the stone very hard to resist.” She looked awfully grim! “Do you agree, Miss Pocket?”

“Not at all, dear. The necklace didn’t tempt me for a moment. And as for someone stealing it, fear not—I will take your advice and find a suitable hiding spot.”

“I am glad to hear it.” Funny, though, she didn’t looked terribly pleased—and I knew why. This wasn’t about some silly diamond.

“Forgive me,” I said, taking Miss Frost’s hand in mine, “but I can see from the pinched look upon your face that you have a heavy heart.”

She looked startled. Just for a moment. Then it passed, and Miss Frost smiled as if she hadn’t a care in the world. “Do I?”

“You mustn’t be embarrassed,” I told her. “Spinsterhood is no great crime.”

She frowned, pulled her hand away. “I beg your pardon?”

“Spinsterhood.” I said it slowly so she would understand my meaning. “You find yourself without prospects—heartbreakingly grim and monstrously unattached. This sort of thing is terribly common among book-loving, sour-faced governesses, so you are not alone. Do not give up hope! I feel certain there is a humpbacked footman or a toothless blacksmith just waiting to sweep you off your feet.”

Miss Frost looked as if she had been sucking on a particularly sour grapefruit. Which was thrilling. Then she tucked the dictionary under her arm and stalked off towards the summerhhouse. She may have muttered something about washing my mouth out with soap.

But I can’t be sure.

Filled with the warm glow that comes when you have helped a fellow traveler in need, I set off to find the perfect hiding spot for the Clock Diamond.