Chapter 6

S: SUSTAINING PRACTICES

Beth

Beth is a hard-charging Manhattan publishing executive. When I first met her at Canyon Ranch, her routine was simply depleting. Dinner was takeout or going out with business associates to cocktail parties or restaurants—near-constant work-related socializing. She went to bed around midnight with a stack of spreadsheets and book manuscripts, so she didn’t actually fall asleep until around two a.m. If iPads and smartphones had been around when I first started working with her, she would have gone to bed with them too—so many of my clients now glow in the dark as they catch up on the day’s e-mails and Web surfing.

Beth admitted to me that her batteries were running down. Her weight was up, her energy was down and the usual middle-age warning lights were flashing—elevated cholesterol and blood pressure. While she was at the Ranch, she braved the scale and the number that came up got her attention. Still, she didn’t deprive herself at mealtimes—the delicious, healthy cuisine was a big part of the draw. But eating at regular hours, going to bed earlier and being physically active in the morning—she loved the nature walks—had an effect after just a couple of days. She was hungry for breakfast in the morning, getting back in tune with her body’s natural rhythms. When we checked in on the last day of her five-day stay, she was surprised that she had dropped four pounds, something she’d long written off as impossible.

When I worked with Beth after her stay, we made some permanent changes in her routine that paid off. When she went out in the evenings to social events, she alternated glasses of club soda with a splash of bitters with her usual wine, cutting down on the empty calories. I can’t say Beth became an ardent home cook, but she held on to the concept of healthy portion size no matter where she was eating, and she ordered meals she never would have dreamed of ordering before—fish rather than steak; a side salad and vegetable instead of fries; fruit for dessert. And she joined a gym and had a personal trainer who made sure she stuck to her moderate exercise routine three times a week. She put down her work an hour before bedtime with rare exceptions, and turned to her wish list of novels she’d wanted to read for years! Nothing radical, nothing that pushed her too far outside of her comfort zone. The weight kept coming off and in less than two years she’d lost thirty-five pounds and had gotten a clean bill of health from her physician. Best of all, she has maintained her weight and health to this day, and I have no doubt into the future.

In Chapter 2, we learned about how the mind and gut are connected and how everything from ideas and emotions to the timing of your meals can affect digestion and weight. In Chapters 3 and 4, we learned about the nuts and bolts of healthy eating and weight loss: which foods to eliminate or restrict; which foods nourish the body and promote healthy digestion and weight. Chapter 5 was devoted to supplements, how supplements can provide significant “value added,” with probiotics in particular bringing us closer to an era of individually tailored “microbiomatic” health and weight loss.

So what’s left? Chapter 6, “S: Sustaining Practices,” is about everything else! It’s about how you live most of your life. The everyday routines we develop, or fall back into, will, in large measure, determine whether we will continue to make smart eating choices and stay on the nourishing life course we’ve set for ourselves. You may recall that I ended Chapter 1 with the idea that successful weight loss and digestive health was about “digesting” your life as a whole.

Consider my client Beth, the high-powered New York City publishing executive. I began working with her before most of the new microbiome research was even dreamed of. Even if that research had been available to provide a nutritional blueprint, she was never going to be meticulous in her approach to cooking and eating. But just making some simple changes to reboot a manifestly unhealthy lifestyle, without pushing a meal plan that was more rigorous than her temperament would tolerate, made such a difference. In the Swift Diet, when we combine a healthy lifestyle with a mostly plant-food, mostly home-cooked diet that operates in sync with the microbiome, even bigger things are possible.

In 2012, I served on a panel that was convened by Lieutenant General Patricia Horoho, the U.S. Army surgeon general, to discuss a program she was spearheading to improve the health of our armed forces. Traditionally, army doctors were mostly concerned with patching up soldiers after combat. But Lieutenant General Horoho was facing a scenario where three out of four young Americans weren’t even eligible for military service in large measure because of weight and medical issues. And so she was consulting a wide range of health care professionals to develop a program to get at the root of this rot. She called it “the Triad”: sleep, exercise and nutrition. I think the army surgeon general picked her targets well.

In this chapter, I’m going to zero in on two major areas, sleep and exercise, which provide a lifestyle foundation for the eating plan that follows in the next chapter. Sleep, exercise and nutrition really do form an interlocking triad. Think about it. Good, sufficient sleep provides us with the physical energy required to do the exercise that revs up the metabolism and builds the lean muscle tissue that burns calories and promotes weight loss. It also contributes to the mental clarity and positive mood that we need to continue to make smart food choices. Bad, insufficient sleep? We’re liable to slip into a groggy state of distraction that is a recipe for falling off the wagon. And insufficient sleep undoes us at the biochemical level as well. It drives up levels of our primary stress hormone, cortisol, which pumps up the body’s production of insulin and drives cravings for sweets and fast-digesting carbs. In turn, regular exercise promotes a good night’s sleep—when the body is tired, in a healthy way, the mind tends to shut off when we turn off the light at night. And especially for people who suffer from the common health problem of sleep apnea, losing weight can dramatically improve the quality of their sleep. The arrows connecting the three elements of the triad run in every direction you can imagine.

This isn’t just for beginners. I have clients who are very successful at losing weight by following the diet changes I lay out and then eventually—it’s the same for any woman on any diet—the progress will slow down or even halt, sometimes before they reach their personal goals. This is the plateau phase. That’s when we need to reboot the lifestyle elements that are keeping you stuck at a weight that you’re not happy with or suffering unpleasant (or worse) digestive symptoms. Beyond sleep and exercise, in the second half of this chapter we’ll shift the focus inward, introducing some basics from two mind-body traditions, yoga and qigong. If improving your sleep and exercise was about getting your body in tune with the demands of the external world, this is about getting in tune with yourself!

At an obvious level, these mind-body techniques reduce stress and, as we discussed, calm the stress hormones that drive carb cravings. But in a subtler way, by encouraging us to focus all of our attention on synchronizing the breath with a few relatively simple movements, they train us to block out the noise of everyday life and to be more present and in touch with ourselves as physical and even spiritual beings.

So, in a sense, we’re finishing up the MENDS program where we began. In the M step we learned to bring attention to the way we eat and to begin to get a handle on the fears and anxieties that overstimulate the enteric nervous system. In this final section of the S chapter, we’ll learn a few systematic techniques to detach from those anxieties and lessen their grip.

Sleep: The Big Recharge

The more we learn about sleep, the more important it becomes. A brand-new avenue of research keys in on sleep as the brain’s way to get rid of waste products in much the same way as the lymphatic system drains off waste from the rest of the body. It may well be that getting the seven to nine hours that sleep experts think most people need is the best way to protect against the excessive buildup of brain plaque that’s implicated in neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s. That’s in addition to the established research linking poor sleep with increased rates of obesity, type 2 diabetes, high blood pressure, heart disease and premature death!

Indisputably, the lack of quality sleep drives weight gain and digestive problems, our main concerns here. The digestive part of the equation will probably come as no surprise. I imagine we’ve all had the experience of having to get up after only a few hours of sleep and discovering that our insides were in an uproar. Stress and sleep disruption have been found to affect gut motility—the speed at which the digestive system sends waste out of the body, sometimes too quickly, sometimes not fast enough, depending on the individual. The weight gain aspect is less obvious, more insidious, and women in particular seem more susceptible. In one recent in-patient study, subjects in a hospital setting were restricted to five hours of sleep for five nights, the equivalent of a stressed-out week of work deadlines and family responsibilities, and then allowed to sleep as long as they wanted for another five nights, up to nine hours a night. The men’s weight fluctuated by only a small amount but the women gained on average about a pound on the sleep deprivation regimen and lost about half a pound with generous sleep.

So what’s going on here? It won’t surprise you by now that the gut microbiome is likely involved. Some interesting research showed that disrupting the sleep/wake cycle of mice increased the permeability or “leakiness” of their gut wall, which sets the stage for systemic inflammation and MicroObesity. Beyond the theoretical level, we know that lack of sleep is a body stressor that pumps up cortisol, associated with increased production of insulin, our fat-storage hormone, and, consequently, abdominal fat deposition. This makes sense in evolutionary terms. If you’re trying to evade predators or survive long stretches without food, it’s a handy thing to have a reserve energy supply around your middle. In our modern world, it’s a disaster. These days, researchers consider chronic sleep deprivation a risk factor for insulin resistance, as in, what happens when the cells stop responding to all that extra insulin. Insulin resistance is the royal road to obesity, metabolic syndrome and, ultimately, type 2 diabetes.

The latest experimental work on sleep and weight gain goes beyond the hormonal explanations to look at how sleep deprivation, especially going to bed late, encourages gratuitous snacking. The researchers call it “emotional disinhibition.” You can think of it as motive meeting opportunity. It’s late at night, maybe you’re zoned out watching TV and you reach for a cookie and then a few more, or a bag of chips. Or maybe you’re hard at work on some important project and you feel the need for some extra calories to keep your brain fueled. You’re right; the brain consumes about 70 percent of the glucose the body takes in, and the longer you’re awake and the harder you’re thinking, the more fuel you need. But night owls habitually overcompensate and eat more than what’s required. Whatever the combination of physiology, psychology and environment—and it surely varies from person to person—the late-night lifestyle is a recipe for weight gain. Here’s my plan to combat it.

Circadian Rhythms and Chronobiology

Sleep is actually part of a larger story about how our body is governed by its circadian rhythms. Think of these rhythms collectively as a timer in the cells of the body, synchronized to the patterns of light and dark over the course of a twenty-four-hour day. A new science has even grown up, chronobiology, that has discovered “clock genes” distributed throughout the cells of the body that in turn answer to a “master clock” located in the hypothalamus in the brain. These clocks help regulate a host of critical body processes, including the sleep/wake cycle, body temperature and the secretion of hormones. And when we depart too far from the way the system is genetically programmed, we pay a price. We’re resilient, so an out-of-sorts week is unlikely to do us any permanent harm. But when we routinely take our meals at all hours of the day and night, the gut will likely register upset. (Yes, there is a “gut clock.”) When we habitually keep strange hours and don’t get enough quality sleep, we’re at increased risk for everything from obesity to heart disease. This last one cuts especially close to home. My father was a shift worker in upstate New York and I strongly suspected the topsy-turvy hours he kept at his job contributed to his being overweight and then dying young from heart disease. The first paper I ever wrote as a nutrition undergrad in the seventies looked at this link between circadian rhythms and obesity.

Rhythm is such a powerful concept when we’re thinking about how we want to address the day, not just for weight loss and digestive health, but for pleasure too! Most days should unfold with a predictable and reassuring rhythm, and meals are important rituals that are part of that flow.

The “Nature Cure”

Another big piece of that daily rhythm that’s all too often ignored is spending time outdoors. At a purely physiological level, exposure to natural light fine-tunes our circadian rhythms and has a positive effect on mood. Researchers have discovered, for instance, that exposure to early-morning sun is an important natural check against depression and a potent natural antidepression therapy. Outdoor exercise is of course hugely beneficial—we’ll get to that in the next section.

But there’s something about being in nature itself, whether you’re walking on a trail or just sitting on a park bench, that confers its own independent benefit. You don’t have to book a trip to a national park. Any place where you share the space with some trees and plants and, if you’re lucky, animals besides humans, will do the trick. The Harvard biologist E. O. Wilson coined the term biophilia to describe the human need to experience other species, and by extension the landscape they inhabit. Nature takes us out of ourselves and our preoccupations. Being in nature becomes a kind of meditation, whether we choose to think about it that way or not. Living in the Berkshires, I’m lucky enough to have easy access to a network of forests and hiking trails. My friend and coauthor Joe Hooper is a Manhattanite who credits short near-daily visits to Central Park with preserving the sanity of a longtime freelance writer.

I’m guessing most of you have had similar experiences even if you’re not currently budgeting your time to make room for them. But I believe you should, even if it’s just having lunch a few times a week in a local park or on the outdoor office picnic bench. The physical reality of nature is probably our best antidote for the unreality of a work life dominated by the computer, our downtime by TV and our social life (at any rate, our kids’ social lives) by digital social media.

Richard Louv, author of The Nature Principle, dubs the effect “vitamin N,” and it’s supported scientific literature that has begun to measure its health and weight effects. In one study from the University of Essex in England, the same group of people took two walks of the same duration, through a country park and an indoor mall. While almost everyone in the group experienced a mood lift outdoors, 22 percent were more depressed after the mall walk! In a study in American Journal of Preventive Medicine, the researchers looked at the lives of over thirty-eight hundred inner-city children and found that, on average, the greener their neighborhoods, the lower the kids’ body mass index!

Exercise: The Weight-Loss Edge

Exercise is, of course, a fantastic mood lifter, sleep enhancer and stress fighter. If you could patent it and put it in a pill, you’d have the most broadly effective and safest drug in the world. Studies have found exercise to be as good as or better than drugs in treating mild depression, and in a landmark 2013 study coauthored by Stanford epidemiologist Dr. John Ioannidis, exercise tested out about as well as drugs in the treatment of four common killers—heart disease, chronic heart failure, stroke and diabetes—without side effects.

When it comes to weight loss and digestive health, it’s hard to overstate how good exercise can be for you. It may promote the growth of friendly bacteria in the gut. Getting moving certainly has the effect of getting the bowels moving, and constipation can set in motion all sorts of digestive problems you’d rather not deal with. When you’re working out, you’re doing a lot of things that the GI system appreciates:

- You’re increasing the forces of gravity that are helping to send waste out of the system.

- You’re stimulating the body’s production of nitric oxide, which protects the mucous lining of the gut.

- You’re also stimulating the body’s lymphatic system, another waste removal system, which protects against bloating.

The pioneer in the field of digestive health and exercise—in the entire field of women and digestive health, actually—is Dr. Robynne Chutkan, a Georgetown University gastroenterologist and the founder of the Digestive Center for Women. Her book, Gutbliss, is a wonderful guide to the gut, and the nonprofit group she founded, GUTRUNNERS (gutrunners.com), works to bring attention to digestive health, with a special emphasis on exercise.

Most weight-loss veterans will tell you that losing weight is not nearly as challenging as keeping it from coming back. Here is where exercise really shines. One of my heroes in the obesity field, Dr. Rena Wing at Brown University, maintains a National Weight Control Registry of about ten thousand people, most of them women, who have lost a lot of weight (the average is seventy pounds) and kept it off for at least six years. The statistic that jumps out from this pool of weight-loss maintainers: they exercise, on average, the equivalent of a daily four-mile walk. If your weight-loss goals are more modest, you may not have to be quite as religious about exercise. But I and most of my clients are out there most days of the week doing something or some combination of things: walking, hiking, jogging, cycling, swimming laps, doing Pilates, Rollerblading, you name it.

An essential key is matching the person with the exercise that speaks to her.

Walking is perfect for the woman who hasn’t been physically active for years, and swimming for the woman who is ready for something more physically demanding but who has joint issues. I’ve found Pilates often works well as one exercise component for women entering the perimenopausal years. Experiencing hormonally influenced weight gain, they want to regain control of their core. In the case of sports like jogging and cycling, it’s often a question of recovering what you used to do and reclaiming it in the present.

My friend Reba Schecter, for twenty years the director of exercise physiology and physical therapy at Canyon Ranch in the Berkshires, puts it this way: “The best exercise is one that you enjoy doing. At any rate, you’ve got to enjoy it enough to keep doing it!”

Reba developed an exercise template for the Swift Diet that covers all the major fitness elements: cardio, strength, flexibility and balance. It provides the missing ingredient for those of us who know we need an exercise routine to supplement our weight-loss program but don’t currently have one: structure. The program is self-paced, but you’ll want to begin with some professional guidance. First, see your doctor and make sure that you don’t have medical issues that would stand in the way of an exercise program that increases in intensity. Then consult with a physical therapist or an exercise physiologist for a session or two to go over any muscle and joint issues that need to be addressed. If you’ve been out of the game for a while, they’ll provide a reintroduction to some exercise and exercise equipment basics. Then, if you choose, you’re on your own. Or, if your schedule and finances permit, you might work with a knowledgeable trainer, either at a gym or at your house. For those of us whose motivation is a little shaky at the outset, this can be a great way to go.

The Cardio Burn

Let’s tackle the elements in Reba’s template, one at a time. Cardio is the most important. The endurance work is where you’re going to get the steady calorie burn and what you’re going to devote the most time to every week. It’s mostly in the aerobic range; in other words, done at a comfortable pace where you can still carry on a conversation. Which activity you choose for the cardio work is up to you. It could be walking or jogging or cycling or, if you have access to a pool, swimming or pool aerobics. If you happen to live near a body of water bigger than a pool, kayaking or sculling is on the menu. The cardio machines at the gym are also fine, as is a vigorous sport like tennis (singles, not doubles). Mix and match as you see fit. The prescription is thirty minutes a day of cardio, done five to seven days a week. If you can do the routine every day without feeling washed out, do it; you’ll reach your weight-loss goals that much faster. If you find yourself craving a rest day or two a week, take them. However, and this is a big however, if you suffer from a chronic pain or chronic fatigue syndrome, go much more cautiously. Exercise is therapeutic here, but in smaller doses. Work out every other day and carefully monitor how you’re feeling. At the first sign of worsening symptoms, dial it back. Be sensitive to how much your body can and wants to handle. If at first you need to spread the thirty minutes out into two or three increments over the course of the day, that’s fine.

As you’ll see in Reba’s list, this is a graduated program that gets more challenging as it progresses over three phases. How fast you progress is up to you. When the physical demands of a phase become routine and intuitively you feel you can move up to the next phase, give it a try. You might need a month in Phase 1, especially if you’re reintroducing exercise after an extended time off. Even though the duration of the Phase 1 and Phase 2 cardio sessions is the same, thirty minutes, Phase 2 is more challenging because of the higher-intensity interval workouts. You might stay there longer, six weeks, for example. Phase 3, for long-term maintenance, devotes one session a week to an hour workout (more if you can handle it). These sustained efforts burn a lot of calories and train your metabolism to draw on fat stores for fuel. But variety is important here—you don’t want to overtax the same muscles you’ve been training all week. So, for instance, if you jog your regular half-hour cardio sessions, the hour-long session might be a bike ride.

Reba uses a “perceived exertion scale,” from 1 to 10, to measure the intensity with which you do the sessions. A relaxed steady lope might be a 5, a peppier effort might be a 7, and above 8, you’re pushing into the anaerobic range—talking is difficult or impossible; breathing becomes deeper and faster and a bit labored. You’ll only be able to sustain this for a minute or two at a time.

In Phase 2, every third session will be an interval workout. You’ll alternate going hard for two minutes (perceived exertion in the 8 to 9 range), running or swimming or cycling or whatever you’re doing, and then going easy for two minutes (perceived exertion below 5), for a total of thirty minutes. You’ll burn a lot more calories at these higher intensities.

Cardio Program

Phase 1 / Building a Base

Activity: Walking, Swimming, Pool Aerobics, Paddling, Kayaking, Rowing, Elliptical, etc.

Duration: 30 minutes

Intensity: Any effort that you can maintain comfortably at a steady pace; perceived exertion 5 to 7 on a scale of 1 to 10

Frequency: Five to seven days per week

Phase 2 / Adding Intensity and Intervals

Activity: Walking, Swimming, Pool Aerobics, Paddling, Kayaking, Rowing, Elliptical, etc.

Duration: 30 minutes

Intensity: Every third day becomes interval training day: alternate 2 minutes hard, 2 minutes recovery; perceived exertion is 8 to 9, followed by recovery below 5.

Frequency: Five to seven days per week

Phase 3 / Increasing Duration

Activity: Walking, Swimming, Pool Aerobics, Paddling, Kayaking, Rowing, Elliptical, etc.

Duration: 30 minutes, including the interval session every third day. But lengthen one noninterval session per week to 60+ minutes

Intensity: This longer session can begin at a perceived exertion of 6 and progress to 7

Frequency: Five to seven days per week

Sculpting the Body: Body Composition

Addressing strength work brings us to the subject of body composition. It’s incredibly important! Women can pay so much attention to the number on the scale, they ignore their muscle tone, specifically how much fat and how much lean muscle their frames are carrying. (Dress or slacks size is a better indicator of body composition than weight, but it’s far from perfect—witness the number of thin, unfit women, the TOFIs, “thin on the outside, fat on the inside.”) Having an adequate amount of muscle offers protection against the metabolic ravages of aging, like type 2 diabetes and heart disease, as well as against falls in the senior years that too often result in a broken hip and a loss of independence. There is weight-loss payoff as well. Increasing our muscle mass will increase our resting metabolism; in other words, the amount of calories we burn just by being alive. “It’s a small but significant effect,” Reba says. “And we want to use every advantage we have.”

So how much time you invest in strength training every week will, according to Reba’s plan, depend on how much you need it. If you are low on muscle based on your body fat measurement, work up to three sessions per week of thirty to sixty minutes each. Check the list on the next page that breaks out four measurable aspects of body shape. The most common, body mass index or BMI, is probably the least useful because it doesn’t make a distinction between muscle weight and fat weight. But if you don’t fall within the recommended range for any of the other three measures—waist circumference, waist-hip ratio, or the body adiposity index (BAI)—then we’re going to recommend three strength workouts a week, in addition to the five to seven cardio sessions. Otherwise, two strength sessions will do the trick.

Of these three body measures, the one you likely won’t be familiar with is the body adiposity index. Emerging research suggests that for women, your BAI score may be a better predictor of heart health than other conventional body shape measurements. And no math required. Just go on the Web site listed in the table, plug in your gender, age, height and hip circumference, and receive your number. Or, if you prefer, go to the gym and get a trainer to measure skinfolds with a caliper. You should get a similarly useful result.

Body Mass Index (BMI)

What it measures and optimal target:

- Height and weight are used to calculate BMI.

- A BMI of 18–25 is considered to be in the healthy range.

What it means:

- Limited value since it does not take into account one’s body composition (muscle, bone, water).

- Assess other markers along with BMI.

Waist Circumference* (inches)

What it measures and optimal target:

- Waist measurement of less than 35 inches (women).

- Waist measurement of less than 43 inches (men).

What it means:

- High waist measurements are associated with more abdominal and visceral fat (fat around organs) and health risks (diabetes, heart disease, cancer).

Waist: Hip Ratio (W:H)

What it measures and optimal target:

- W:H range less than .8–.86 (women)

- W:H range less than 1.0 (men)

What it means:

- Another measure of health risks associated with excess abdominal and visceral fat.

Body Composition

What it measures and optimal target:

- Can be measured a number of different ways, including special scales, skinfold calipers, etc.

- Body adiposity index (BAI) is a newer estimate of body fat.

What it means:

- BAI is derived from a calculation that takes into account gender, age, height, and hip circumference.

- Calculate your BAI at: http://easycalculation.com/health/body-adiposity-index.php.

- A healthy range of body fat is gender and age specific; go to the link above and see the interpretation based on the research to date.

Healthy BAI Ranges

|

AGE |

WOMEN |

MEN |

|

20–39 |

21–33% |

8–21% |

|

40–59 |

23–35% |

11–23% |

|

60–79 |

25–38% |

13–25% |

How you want to go about getting stronger is up to you. It might be anything from resistance bands or dumbbells and ankle weights that you can use at home to making use of the full complement of resistance training machines at a gym. To get results, and to avoid getting hurt, you need to know what you’re doing. That means working with a trainer or a physical therapist at least for the first couple of sessions. And you need to make sure that you’re working out the six major muscle groups: chest, upper back, shoulders, abdomen, lower back and lower body. (Pilates is a great toner for the core muscles in the abdomen and the lower back, but just because you may have a wonderful Pilates class, don’t think that you can skip the other four muscle groups!)

As you’ll see in Reba’s list below, you move through three phases. Progress is individual but a reasonable benchmark might be:

- Four to six weeks in Phase 1

- Four to six weeks in Phase 2

- Phase 3 for long-term maintenance

The frequency stays the same—two or three sessions per week, which should take no more than thirty minutes per session—but, no surprise, the challenge increases. In Phase 2, for example, you’ll do fewer repetitions at higher intensity (stiffer resistance) before hitting the fatigue wall, when you no longer have enough strength to do another repetition with proper form. (What constitutes proper form depends on the exercise. Follow your trainer’s lead.) In Phase 3, you’ll stay at this higher intensity—it’s a more efficient way to build muscle—but you’ll be doing two sets of exercises for each muscle group, not one.

Strength Training Regimen

Phase 1

Duration: Suggested four to six weeks

Type: Six major muscle groups

Mode: Any (handheld weights, machines, water weights, body weight, resistance bands, etc.)

Frequency: Two to three times per week, depending on body fat measurement

Sets: One per area

Intensity: 10 to 15 reps to fatigue

Phase 2

Duration: Suggested four to six weeks

Type: Six major muscle groups

Mode: Any (handheld weights, machines, water weights, body weight, resistance bands, etc.)

Frequency: Two to three times per week, depending on body fat measurement

Sets: One per area

Intensity: Increase resistance; 8 to 12 reps to fatigue

Phase 3

Duration: Maintenance

Type: Six major muscle groups

Mode: Any (handheld weights, machines, water weights, body weight, resistance bands, etc.)

Frequency: Two to three times per week, depending on body fat measurement

Sets: Two per area

Intensity: 8 to 12 reps to fatigue

Flexibility and Balance

At the end of a full session, thirty minutes of cardio, twenty to thirty minutes of strength work, finish out with five to ten minutes of stretching. The muscles will be warmed up and more malleable then. A physical therapist can help you recognize tight muscles that will benefit from stretching and work with you on a personalized stretching routine that hits the key muscles. The usual drill: holding a stretch for twenty to thirty seconds in a static position to lengthen the soft tissues.

In a weight-loss-oriented program, you may not need special work on balance unless you’re training to get better at a particular sport. Take this test: stand on one leg and bring the other leg up so that the thigh is parallel to the floor. If you can hold that position for thirty seconds without holding on to anything and without much wobble, you pass—balance exercises don’t need to be a priority now. (But make sure to test both legs.) If you can’t balance for thirty seconds, then incorporate five to ten minutes of these leg lifts into your workout until your balance improves.

Work Spa

Making time for exercise is an issue for most of us. One tip: you can subtract minutes from your dedicated workouts by putting in some minutes at the office. Stair walking is a great cardio workout for the high-rise-office set. And here are two resistance exercises that can be done in an office setting without attracting too much attention to yourself. Besides building up strength and flexibility, you’re relieving stress and breaking up the amount of time you spend motionless in your chair—some researchers consider prolonged sitting to be a health risk factor on par with smoking!

1. Core/lower-body exercise: Stand, holding the back of a stable chair for balance. Sink into a squat position, pushing hips far back and lowering until thighs are parallel to the floor. Use core and legs to stand, lifting the chest. Or you can invest in a stability ball. Sitting and balancing on it, you’re working your core and leg muscles continuously without even thinking about it. If a large inflatable ball would attract too many stares in the office, use it at the beginning or the end of the workday or during the lunch hour.

2. Back/posture exercise: While either sitting or standing, grab a resistance band at either end and place it in front of you, across your body at chest level, your elbows bent at ninety degrees. At the start, your hands should be slightly wider than shoulder width apart. Then tighten the abdominal muscles and stretch the band by bringing your shoulder blades together. Hold for ten seconds. Slowly return to the original position and relax for ten seconds. Repeat ten times.

Mind-Body-Spirit

Marian

I work with a lot of busy doctors like Marian, who has a thriving family-medicine practice in the Berkshires that doesn’t leave her much time to take care of herself. I’d been seeing Marian for a few weeks for that stubborn ten-pound weight issue along with an assortment of digestive symptoms, and we weren’t seeing much change. Then we decided to tackle her stress issues head-on. I got her to agree to do a simple belly-breathing exercise in between patient visits, when she was updating her records—she put a Post-it on her computer screen to remind herself. Then I encouraged her to take a good look at her office, where she spent so many hours during the day. Did it reflect a healing environment? She added some plants and a bowl of fresh fruit on her desk. And we found a yoga class in the area that she tries to get to twice a week, most weeks. It’s enough to get her to begin to catch her breath, to appreciate her work as a healer for her patients and how important it is to take care of herself. These simple changes led to some other healthier choices, and two months in, Marian had lost five of the ten pounds that were bothering her and her irritable bowel symptoms had markedly improved. As it turned out, her eating habits weren’t the main issue. It was the rest of her life.

I’ve been using a techniques like affirmation and visualizations with my nutrition clients for most of my career. But when I came to Kripalu seven years ago, I witnessed the power of mind-body practices such as yoga and qigong to support both weight loss and digestive health. Those of us with weight and gut issues have in some real sense lost touch with our bodies, how they want to look and feel. By focusing our attention on the physical self in a positive way, how we can bend and reach and stretch, even just a few basic techniques can wake us up! Although yoga hails from India and qigong from China, both traditions conceptualize their mission in a strikingly similar way. They are concerned with accessing and intensifying the life energy that courses through us—prana in Sanskrit, qi in Chinese. You could say that the Swift Diet is devoted to strengthening and nourishing the “digestive and metabolic qi”!

Whether you believe in the physical reality of this life energy or not, research strongly suggests that the attention we bring to these mind-body techniques can carry over from the mat to the everyday decisions we make about selecting, preparing and eating our meals. In one of my favorite studies, University of Washington epidemiologist Alan Kristal analyzed data on some fifteen thousand people. Those who had been overweight in their forties but who had taken up yoga for at least four years lost, on average, five pounds in their fifties. Remember, the vast majority of these people were not following a formal weight-loss program. And their counterparts, the ones who had not taken up yoga, gained, on average, eighteen and a half pounds!

An Australian study went the opposite methodological route and studied the intimate thoughts of a small group of overweight women taking a three-month yoga course. In their diaries, the women reported that as they began to feel more connected to their bodies, their eating habits improved: they made healthier food choices, ate less and ate more slowly. And in one small study by an Indian research group, yoga was found to be more effective than conventional drug therapy in treating IBS symptoms.

While the traditional yoga literature speaks to yoga’s health benefits, no less a modern medical authority than Dr. Chutkan, herself a practitioner of yoga, talks about its ability to help relieve uncomfortable symptoms like bloating and gas and to build up the core abdominal muscles that support good gut health. At Kripalu, senior yoga teacher Vandita Kate Marchesiello and I are teaming up to teach simple yoga practices that promote digestive resiliency and increased flexibility, stamina and strength in the muscles and joints.

I’ve enlisted the help of two dear friends to introduce you to some basic yoga and qigong techniques specifically designed to support digestion and weight loss. My qigong teacher, Dr. Yang Yang, who earned a kinesiology PhD at the University of Illinois, teaches this venerable Chinese practice to cancer patients at Manhattan’s prestigious Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center and to students at his own Center for Taiji Studies, also in Manhattan. Yoga instructor Jenne Young teaches yoga at Kripalu and at other studios in the Berkshires as well as to patients at Berkshire Health Systems. Together she and I have co-led nutrition-and-digestive-health-meets-yoga workshops all over the country, including at the famous Rancho La Puerta spa outside of San Diego.

By closing this chapter with techniques drawn from both yoga and qigong, I’m inviting you to try something on, almost like a piece of clothing. Shop this section until you find a few things that fit your life and that you can look forward to doing with joy.

Yoga 101

People are who aren’t so familiar with yoga tend to think of it as a collection of stretching poses. But the tradition, going back to the second-century Indian sage Pantanjali, is much richer than that, encompassing philosophy, meditation, breathing exercise and yes, the poses or asanas. Fundamentally, yoga is about the union of mind, body and spirit. Jenne’s work with our students delves into all of this in a multiday immersion. Here’s a step-by-step introductory session. Experiment with it. Try it out every day for a week. Each posture should take five to ten minutes.

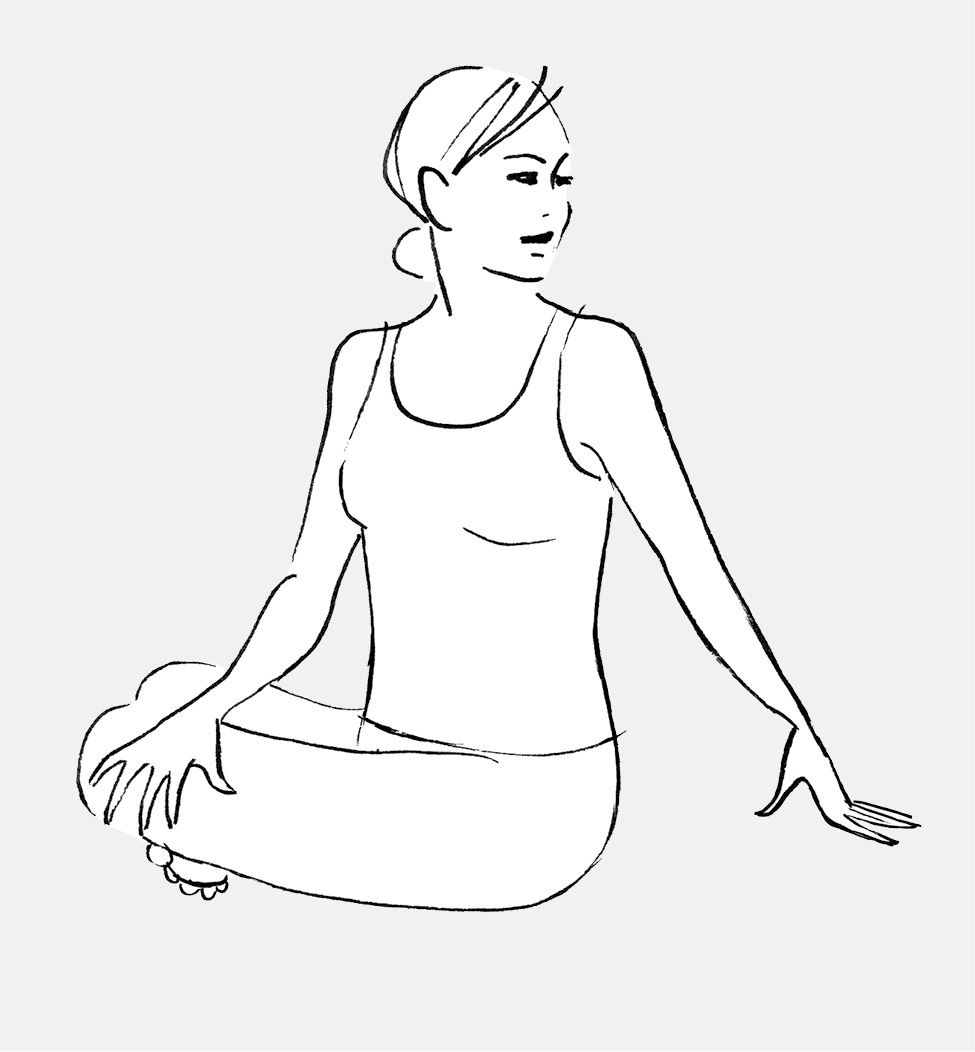

Sitting pose

Equipment: a yoga mat and a cushion or folded blanket.

1. Sitting pose: We’ll start in Sukhasana or “Easy Pose,” a comfortable cross-legged position. Sit on the edge of a folded blanket or cushion to support the natural curvature of your spine. Bending your right knee, bring your right heel in toward your groin. Bring the left foot to rest on the floor in front of your right leg or tuck it beneath the right shin. If you find that your knees are above the hips, add another blanket to raise you up, or support your knees with a cushion or rolled blanket. The idea is not to strain your knees but to allow them to relax. Root your sitting bones down as you lengthen out of the hips. Stack your shoulders over the hips and draw your shoulder blades back and down to open the chest. The crown of your head rises toward the ceiling. Gently tuck your chin to lengthen the back of your neck. Rest your hands on your thighs.

2. Dirgha breath: Still in the sitting position, we’ll begin with a basic breathing exercise, the three-part yogic breath or, as it’s called, Dirgha breath, which means “slow and deep.” In this breath, we use the full capacity of our lungs, warming up the system, oxygenating the blood, getting rid of toxins and calming the body. We’ll do ten Dirgha breaths. For each, slowly begin to inhale, filling the bottom of the lungs. Feel the belly expand. Continue inhaling and feel the middle section of the lungs under the rib cage expand so that the rib cage gently pushes up and out to the sides. Continue inhaling into the upper region of the chest, completely filling the lungs. Slowly exhale, letting go of the breath from the top of the lungs, then from the rib cage and finally exhaling all the air out of the belly. Squeeze the air out with your abdominal muscles, gently pulling the belly button back toward the spine.

Side bends

3. Side bends: Now we’re going to introduce movement, side bends, which are helpful for digestion because they stretch and strengthen the abdominal area and assist in relieving gas. After your last Dirgha breath, inhale and lengthen your torso, arms at your side. On the exhale, press your left hand on the mat. When you inhale, sweep your right arm up and arch it over to the left for a side bend. Keeping your sitting bones evenly grounded, take two full breaths, deepening into the side stretch. On the third inhale, come back to the center. Exhale and press your right hand on the mat. Inhale and sweep your left arm up and over to the right. Take two full breaths here, deepening into the side stretch on the right. On the third inhale, come back to the center. Repeat this two more times on each side. Take your time and enjoy.

Twists

4. Twists: Back to the center and still in the sitting position, we move into twists. Twists can improve digestion by relieving tension in the torso. They massage and stimulate the entire abdominal area, helping to relieve constipation, gas and bloating. To begin, lengthen your arms out to the sides, take your right hand to your left knee and place your left hand behind you, pressing into the floor directly behind your tailbone. Inhale and lengthen the crown of your head toward the ceiling. Exhale and slowly begin to twist your torso to the left. Begin by twisting your belly first, then the rib cage, then the shoulders, gently turning your head to look over your left shoulder. The head is the last thing that turns. Stay in the twist for two full breaths. With each inhale think of lengthening the crown of your head toward the ceiling; with each exhale, deepen into the twist. On the third inhale, begin to slowly unwind back to the center. As you exhale, bring your hands back down by your side. Repeat the twist on the other side. Do a total of three twists on each side.

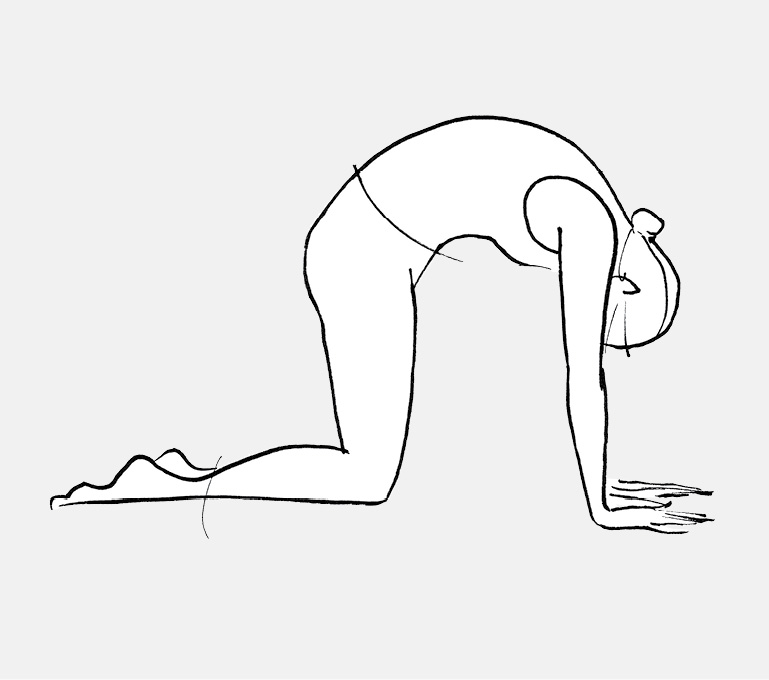

Cat and Cow

5. Cat and Cow: Slow movement between these two poses helps bring circulation to your abdominal organs. It also gently stretches the spine and helps relieve tension there that can disrupt good digestion. From the seated position, come into Table posture by bringing your hands directly under your shoulders. Your hips should be directly over your knees. You can place your blanket under your knees if they need extra support. Spread your fingers out wide and press into your fingers as well as your palms to create a strong foundation. On the inhale, lift your shoulders and tailbone toward the ceiling while you gently press your belly toward the mat. You should be looking straight ahead. On the exhale, drop your tailbone and shoulders toward the mat and begin to round your spine toward the ceiling. Gently tuck your chin toward your chest. Repeat this cow and cat movement five more times. Cow is when the belly is pressing toward the floor; cat posture is when your spine is rounding toward the ceiling.

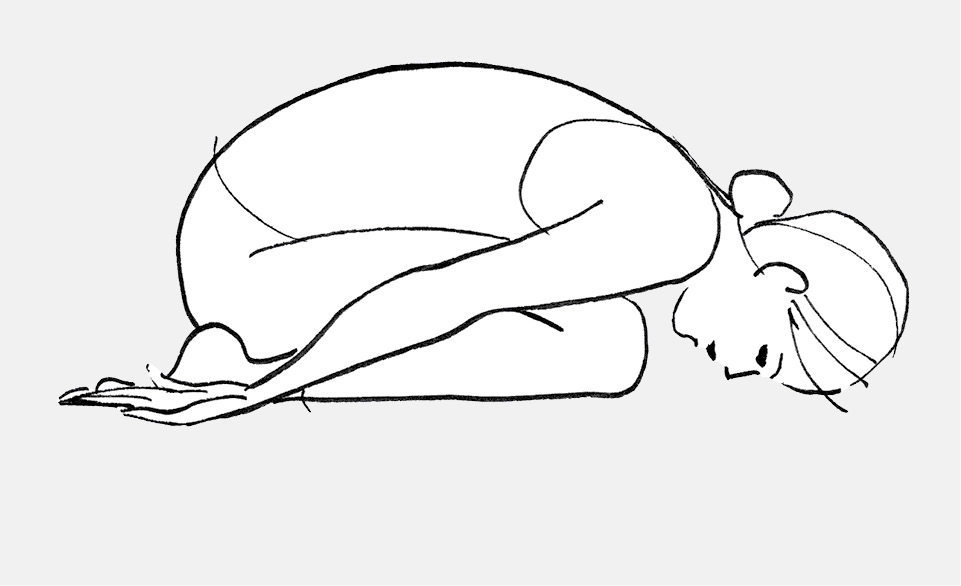

Child

6. Child: Now, we move into the Child pose. This is a resting pose that gently stretches and stimulates the stomach and lower bowels to aid in digestion. It also relaxes the nervous system, essential to good digestion. Come into a neutral Table position and begin to draw your hips back toward your heels. Your belly comes to rest on your thighs; your arms can be out in front or back alongside your legs. Your forehead is resting on the floor or blanket. Relax into this folded posture. After three relaxing breaths, place your palms under your shoulders and push up into a Sukhasana comfortable seated position or whatever you like. Take a couple more cleansing breaths and savor a few minutes of quiet meditation.

Qigong 101

At Kripalu, I’ve had the good fortune to study qigong with many teachers, including Deborah Davis, Roger Jahnke, Robert Peng, Lee Holden and Dr. Yang Yang. Qigong means, literally, “energy work”—qi is the vital energy and gong is work. It’s something of a catchall term that embraces a number of different Chinese traditions, from almost motionless meditations to the exquisitely athletic martial art of t’ai chi.

The career of Dr. Yang Yang is a good illustration of its scope. As a child growing up in China, he was diagnosed with a congenital heart defect. The family steered him to qigong training in hopes that it would improve his health, since expensive surgery during the Cultural Revolution was out of the question. The young Yang Yang outgrew his heart problem and grew into a t’ai chi champion. Now, as a qigong teacher in the States, he has returned to the therapeutic roots of the art, especially at Memorial Sloane Kettering Cancer Center, where he builds up the bodies and the spirits of cancer survivors.

I am a certified teacher in Dr. Yang Yang’s school, but I have no ambition to master any difficult choreography. (“Empty movements,” he calls it; that is, if the student hasn’t developed the meditational foundation.) I, and many of my clients, have fallen in love with simple repetitive movements that are married to the rhythm of the breath. To the outsider, it may look very simple. But when you’re doing it, you feel like you are drawing on and building up an energy, very real and powerful, that can be your ally in weight loss and digestive health.

As for the Western research, it’s in its infancy, but promising. For instance, an Australian study examined whether regular qigong practice would have any physiological impact on a group of forty-one men and women with elevated blood sugar. After three months, the qigong group was found to have improved their blood sugar levels and lost more weight than a comparable group receiving standard medical care.

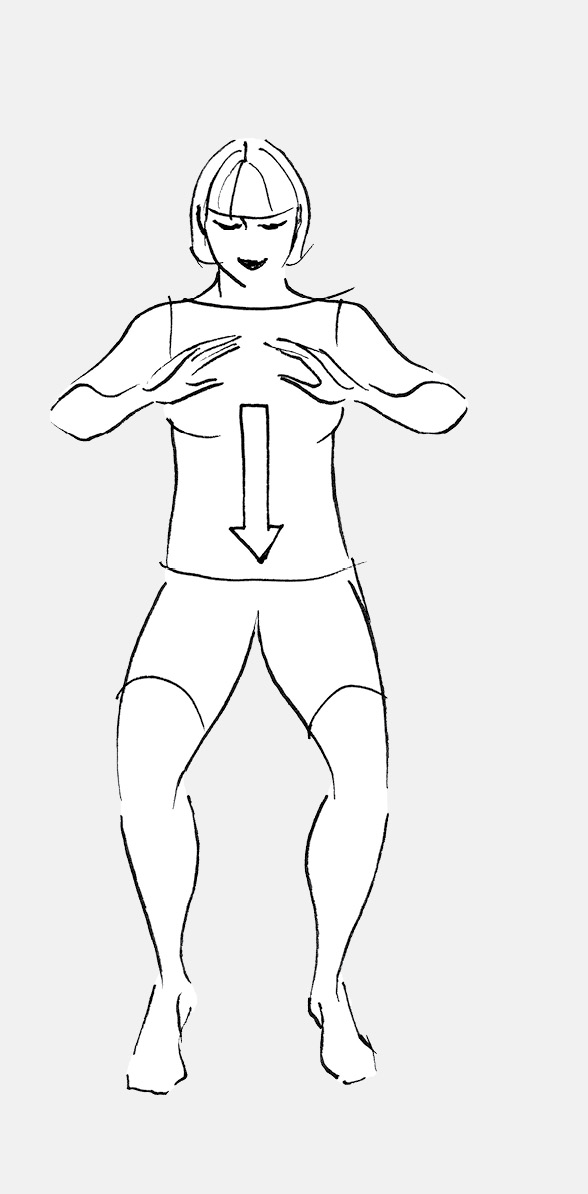

Here are three qigong exercises I’ve adapted from Dr. Yang Yang’s program that will serve as an introduction. Try them for a week and see how you find them. The sequence shouldn’t take more than fifteen minutes—it’s both relaxing and energizing.

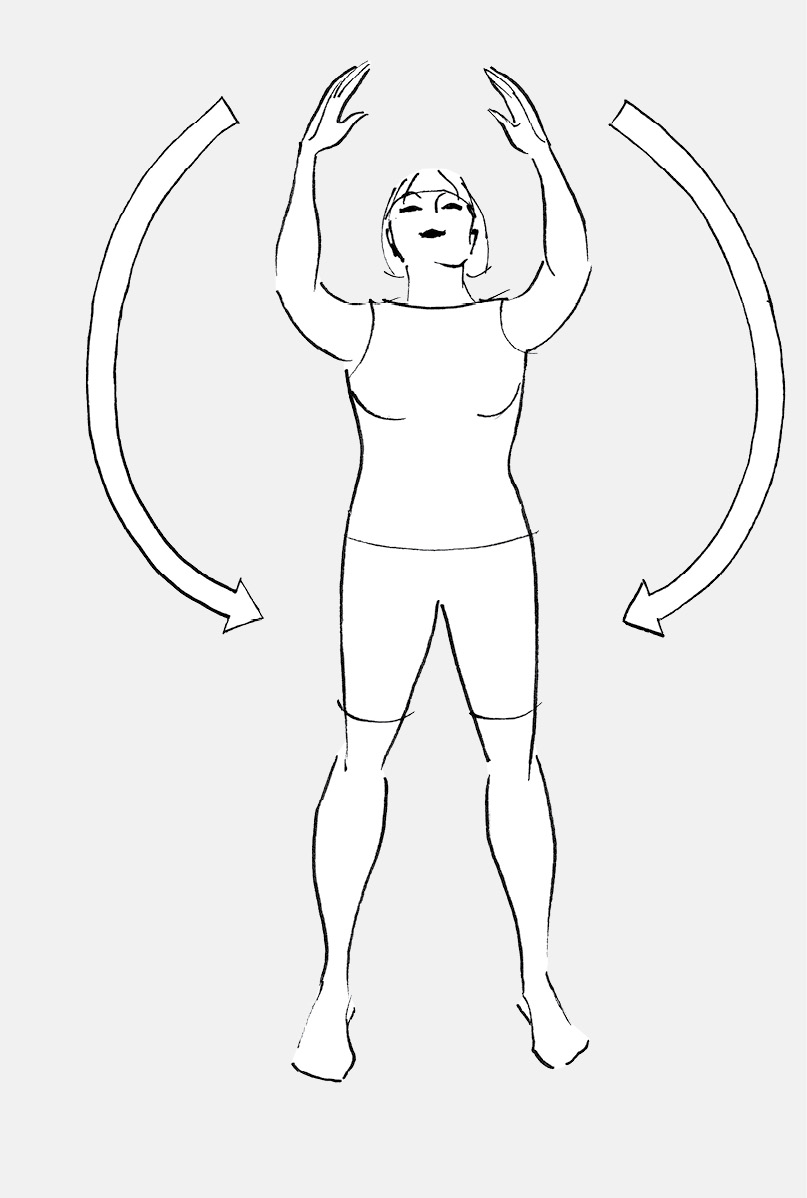

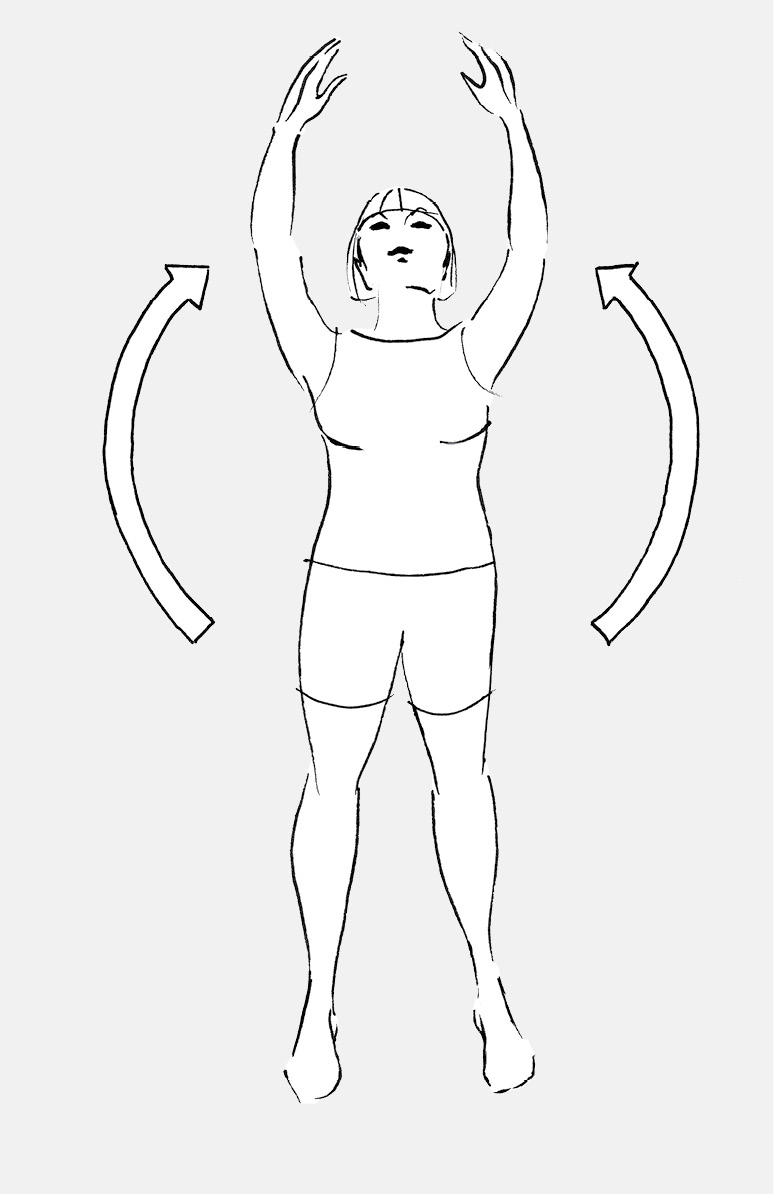

“Grand Opening and Closing” Slow Movement (five minutes): Assume a natural standing stance, feet even, slightly more than shoulder width apart, knees slightly bent. On the inhale, open the chest and extend the arms upward and outward in a circular motion, the palms facing out. Have the intention of rising, of expanding. Feel free to gently shift your weight to one side. On the exhale, close the chest, drop your arms downward and cross them, continuing the circular motion and bending slightly and comfortably at the knee. Have the intention of sinking, of compacting, and move slowly, gracefully, as if you are in water. If you shifted your weight as you rose, then shift your weight to the other side as you contract and come down. Repeat this movement eight times for a total of nine times, and remember to smile!

“Grand Opening and Closing”

Lying Down Qigong Meditation (five minutes): Lie down on a mat or a blanket. Make sure you are comfortable. You are giving the body time to find an optimal resting point. Empty the body! Put your hands on a spot two to three inches below the belly button, your “dantian” or “energy center,” where the qi collects and is distributed throughout the body. Imagine you are stretched out on the beach and your body is slowly sinking into the sand, starting with the head. Picture the imprint of your head in the sand. Move down to the neck, which is sinking, then to your shoulders, then your middle back, lower back and pelvis, one area at a time. Then move down to the lower legs and finally to the feet. As your body is sinking in sequence, scan for any tension; if you notice any, just acknowledge it, breathe and relax. Use your imagination. Don’t push; relax and sink. Close your eyes and ears and imagine your dantian. Have a gentle smile and beautiful day at the beach. If you fall asleep, that’s OK too.

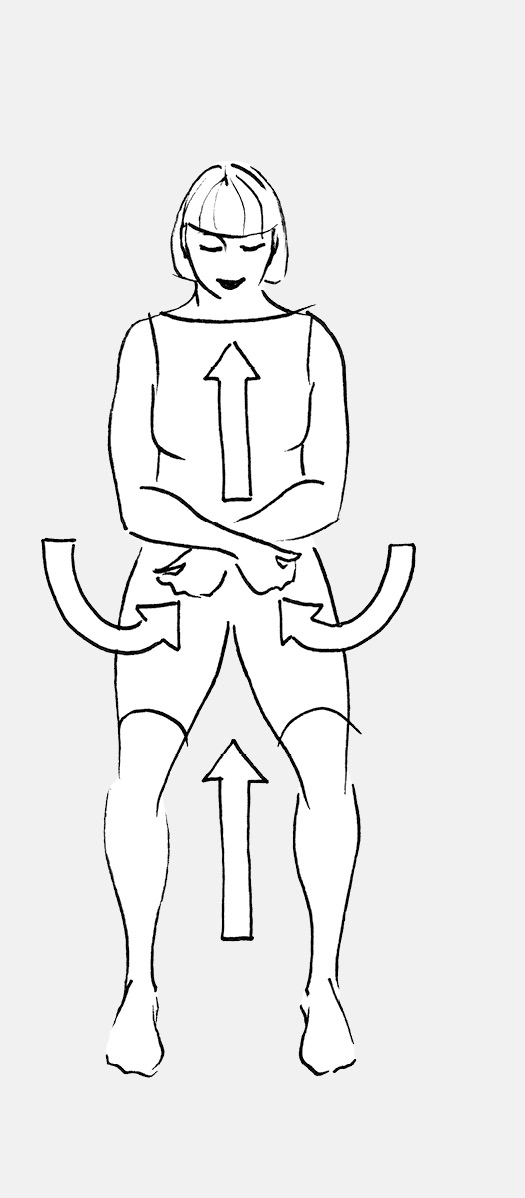

“Washing Organs”

“Washing Organs” Slow Movement (five minutes): Assume a natural stance, feet even, slightly more than shoulder width apart. Begin with your arms gently resting at your sides. Breathe normally. Bring both arms out to the side and raise them up over your head, following the slow movement with your eyes, gathering the energy from the universe as you do this. Then, with your palms facing down, let your hands drop very slowly in front of you. Imagine that the energy you gathered from the universe fills each and every cell of your body as your hands float down in front of you, allowing the energy to flow through your body, organs, tissues and cells. Bend the knees slightly and comfortably as your arms come down. Breathe, relax and SMILE! Dr. Yang Yang says, “You are collecting energy from the universe and nature. It can be from the ocean, from the snow, from the mountain.” Repeat this movement eight times for a total of nine times.

Swift Qi

So there you have it, the five elements of MENDS. If we’ve both done our jobs, you’re inspired by the idea of bringing conscious intention into your life—into your food and meal choices, into your daily routines and into the mind-body practices that can rewardingly take us outside those routines. You’ve embraced a philosophy of “whole foods, whole person, whole life.” You are suitably relaxed, open and ready to commit to the 4-week Swift Plan.