Chinese Cosmopolitanism

and Media Use

John Sinclair, Audrey Yue, Gay Hawkins,

Kee Pookong and Josephine Fox

The patterns of Chinese migration represent one of the world’s most impressive and complex cases of the phenomenon of diaspora. At least in the sense of forming a potential television audience on a global scale, we can think of the worldwide diasporic communities of Chinese as an extension of “Greater China”—a virtual “imagined community” or common cultural region united either through the “time–space compression” of satellite broadcasting or, where this is not the case, then instead by the portability and reproducibility of video (Sinclair et al., 1996).

In most countries of the world, both public and commercial television networks within the national boundaries continue to assert their traditional role of generating a sense of national belonging and identity. And in Australia, people of Chinese origin can be expected to be attending to such national media to a greater or lesser extent. However, they also can use media to maintain their links and orientation to a whole cultural world outside their nation of residence by means of “narrowcast” channels for specific markets, such as Chinese-language services on pay television, and other media forms such as video rental and cinema distributed from the Chinese-speaking nations.

It is the questions produced within this tension between the national and the diasporic, the local and the global that motivate the research outlined here. How are audiovisual media, especially television and video, used in the everyday lives of diasporic communities such as the Chinese in Australia? By what processes can and do these people maintain cultural connections with the Chinese world while negotiating a place within the host culture? How are they able to maintain access to Chinese-language audiovisual material? As well as ethnographic investigation, this research incorporates a mapping of the sources of production and the systems of distribution of audiovisual products and services which emanate from the nations comprising Greater China (Mainland China, Taiwan and Hong Kong), so as ultimately to assess the actual patterns of consumption against the political economy of production and distribution.

In order to trace the entire process from local consumption to global production and distribution of Chinese-language media products and services, various lines of investigation were pursued, drawing on a selective mix of methodologies. Institutional studies were made of the main narrowcast television networks, and the actual use of these services was investigated through direct viewer research. Trade research traced the complex entrepreneurial connections between the television programs, films and videos available to Chinese-speakers in Melbourne, and the corporate provenance of this material in Greater China. Finally, consumption in the home of these and other communication media products and services was studied via a two-stage approach involving a household survey linked to more specific, qualitative ethnographic case studies.

The Chinese in Australia: Global Diaspora in Microcosm

Size and Composition of the Chinese-origin Population

From the point of view of how immigrant communities can use communications media, whether to maintain their cultural identity or to adapt to a new environment, the Chinese in Australia provide a valuable case study, as they present a microcosm of both the past and present Chinese global diaspora. In recent decades, major immigrant communities from Mainland China, Hong Kong, Taiwan, Malaysia, Vietnam, and smaller groups from Singapore, East Timor, Indonesia, Cambodia, Papua New Guinea and other parts of the world have settled in various cities of Australia, particularly Melbourne and Sydney. Many have come not directly from Chinese nations, but from the “Nanyang” countries of Southeast Asia to which their ancestors migrated during the century prior to World War II, and where over 15 million “Overseas Chinese” still live (Esman, 1986; Kee, 1995). There is also a large local-born Chinese population which has developed from earlier immigration, comprising a relatively high proportion of third- and even fourth-generation Australians of Chinese descent (Kee and Huck, 1991). The 1991 Census found 261 466 Chinese-speaking persons out of an estimated 400 000 people of Chinese ancestry in Australia (Kee, 1997).

The sources, socioeconomic backgrounds and circumstances of Chinese immigrant arrivals in Australia have been much more diverse than those of Chinese communities in the other great contemporary immigrant-receiving countries such as the United States, Canada, Britain and New Zealand, or earlier immigrant-receiving countries in Southeast Asia, South America, Europe and Africa. The first Chinese migrants, especially those who came during the Gold Rush of the latter half of the nineteenth century, were predominantly from the Cantonese-speaking Sze Yap (Four Districts) of the Pearl River Delta in Guangdong province, but their numbers were drastically decreased by the immigration restrictions against non-Europeans enforced for the first half of the twentieth century—the “White Australia” policy. With the eventual abandonment of such a race-based immigration policy from the late 1950s onwards, and particularly with the progressive “multiculturalism” policy phase of the 1970s and 1980s, Australia has attracted relatively large communities of Chinese from Malaysia, Singapore and Hong Kong, including many who previously had studied in Australian universities. Those from Malaysia in particular enjoy high levels of education and have become concentrated in the professions (Kee, 1995).

By contrast, large numbers of Chinese with relatively few formal qualifications, limited English-language skills, and no prior familiarity with Australia’s still predominantly British values and institutions were admitted in 1978, for the first time in the twentieth century, when the Fraser Coalition government began to accept Indochinese from refugee camps in Southeast Asia. This began a process of diversification that has been extended and consolidated in a quite different direction since the 1980s by the Business Migration Program, which has seen a rapid growth in the numbers of Chinese coming from Taiwan. Whereas many of the Indochinese came with the skills and some also with the capital, which enabled them to set up small businesses, the Taiwanese as a group are much more affluent, and have a low participation in the labour force. This is partly because of the number who continue to travel back to Taiwan to conduct business there—the so-called “astronaut syndrome”, which is very much a part of the contemporary diasporic experience for this type of migrant. The Taiwanese are mainly speakers of Hokkien and Mandarin, unlike their predecessors from Southeast Asia and Hong Kong who mostly came speaking Cantonese and were also fluent in English (Kee, 1997). Importantly, the advent of these business migrants, from Hong Kong as well as Taiwan, gears Australia into the “essentially stateless” business networks of the Overseas Chinese (Langdale, 1997: 307), the powerful informal links underpinning Chinese capitalism, not only in the Asian region, but throughout the diaspora (Kotkin, 1993; Ong, 1997).

Beginning later in the 1980s, an intensification of efforts to attract overseas students into Australian universities led to the resumption of a steady flow of new settlers from the Chinese Mainland, a movement that had terminated earlier in the century, not just as a result of the “White Australia” policy, but also the great political upheavals in the People’s Republic of China (PRC). Prior to the Hawke Labor government’s granting of residence to those PRC nationals who were here before the Tiananmen Massacre in June 1989, and even to a substantial number of those who arrived afterwards, Chinese immigrants in Australia had originated very much from the periphery of China—although, as noted, many were children or grandchildren of earlier Chinese emigrants from Guangdong, or were themselves secondary migrants from China. The new Mainlanders have come mostly from Beijing, Shanghai and Guanzhou. Although the student population of more than 30 000 at the core of the Mainland community has greatly increased the number of Mandarin speakers, and those from Shanghai have added yet another dialect to the varieties of Chinese spoken in Australia, the Cantonese of the earlier groups continues to be predominant (Kee, 1997).

While more favoured with education and creative talent than the great bulk of contemporary Chinese society, the PRC nationals in Australia still reflect Mainland values and behaviour—albeit in highly variable ways, given the differential impact of the cultural, social and political transformations set in play by the Communist Revolution of 1949, the Cultural Revolution of 1966–76 and the more recent socialist market reforms. In contrast, the communities of Chinese in Taiwan, Hong Kong, Malaysia and Singapore have adhered more closely to the traditional forms of Chinese values and practices. Confucian codes of conduct, Buddhism and folk beliefs have influenced the worldview and behaviour of these Overseas Chinese to a greater degree than their counterparts from the Mainland.

Nevertheless, with the significant exception of the Indochinese refugees, the Chinese who have come to Australia generally have high levels of education, as well as a secular outlook. Many are also affluent and well-travelled, and much more cosmopolitan than most other communities which have been formed as a result of postwar immigration. They are predominantly urban, with the Mainlanders, Taiwanese and those from Hong Kong favouring Sydney, while those from Malaysia and Indochina are proportionately better represented in Melbourne (Kee, 1995). However, in Melbourne and the surrounding state of Victoria, where a quarter of the Australian population lives, Mainland China has replaced Vietnam as the main source country of immigrants of Asian origin, with Hong Kong a distant eighth (Department of Immigration and Multicultural Affairs, 1997). Like other world cities with an appreciable Chinese-origin population, Melbourne and Sydney both have a Chinatown in their central business districts, dating from the mid-nineteenth century; there are also clusters of suburbs with a high proportion of recently arrived migrants, as well as more settled—or just more affluent—Chinese-origin families sprinkled throughout their metropolitan areas.

In short, Chinese groups in Australia present a microcosm of the differences within the Chinese diaspora: differences in countries or regions of birth, socioeconomic status, languages, dialects, religions and degree of “de-sinicisation” of values and behaviour. As such, they provide an excellent opportunity for the study of diasporic cultural identities, specifically of the factors which shape the identities of people of Chinese descent on a more universal scale.

The Meaning of Chineseness

Within the Chinese imagination, “China” (zhong guo), as the Middle (zhong) Kingdom (guo), has always glorified itself literally as the centre of the world, designating all non-Chinese as “barbarians” or “red-haired devils”. Such constructions manifest China’s paradoxical relationship to the West, a relationship which is at once negative and affirmative, signifying both fear and desire. In the (imperial) Western imagination, “China” exists, on one hand, in the terms of Edward Said’s discourse of Orientalism, as a primitive, eroticised and exoticised Other. On the other hand, it is also worshipped as the Great (Other) Civilisation, one is that is the opposite, yet equivalent in status, to its Western counterpart. As a postsocialist paradox, China is thus both “empire” and “victim”, caught between the forces of “First World” imperialism and “Third World” nationalism. In more recent times, the exotic homeland myth of China has produced an Oriental form of Orientalism, with the East appropriating the instruments of the West to fantasise itself and the world. Chen Xiaomei (1995) terms this creative discursive practice “Occidentalism”, a process whereby the Chinese Orient obverts the Western construction of China into a Chinese construction of the West.

Within the diaspora, the imaginary homeland of “China” has tended to become the absolute norm for “Chineseness”, against which all other Chinese cultures have to be measured. Discursive concepts such as “Mother China”, “the motherland”, “the fatherland” or “the ancestral land” evoke a nostalgic emotional reverence. Consistent with the mythologised image of traditional China in the critically acclaimed Fifth Generation Chinese films, postcolonial feminist Rey Chow (1991) has argued that Chinese from the Mainland might be seen as more “authentic” than those who are from Taiwan or Hong Kong because the latter have been “Westernised”. Yet such an essentialised concept of “authenticity” implies both an abundance and a lack. Depending on where one is situated with regard to the boundaries which mark out nations as “homes” and “hosts”, it is conceivable that either privilege or disempowerment could be constituted by such notions as “too Chinese” or “not Chinese enough”.

Cultural theorist Ien Ang (1992) offers an autobiographical staging of her own “Chineseness” as a strategy to illuminate the precariousness of diasporic identity, highlighting the very difficulty of constructing a position from which one can speak as (an “Overseas”) Chinese. Originally a speech in English at a Chinese symposium in Taiwan, her essay, aptly entitled “Not Speaking Chinese”, maps a strategic positioning which calls to task the indeterminacy of “Chineseness” as a signifier for “identity”. Tracing the discursive otherness and the incommensurabilities of her life as an Indonesian-Chinese, Peranakan, Dutch-speaking and educated woman living in Australia, Ang argues against the hegemonic condition that “not speaking Chinese” signifies the loss of “authenticity”. She puts the case for the recognition of a heterogeneous “Chineseness”, the meaning of which is not pregiven and fixed, but constantly renegotiated and re-enunciated, both inside and outside China.

A similar argument is articulated by Aihwa Ong and Donald Nonini (1997), who find that the heterogeneity of Chineseness apparent in the emergent cultures of Asian modernity manifests a new Chinese identity that displaces and de-authorises China as the centre of the world. In this perspective, diasporic Chineseness is constituted by deterritorialised Chinese transnational practices operating across all recognised borderlines.

If, on one hand, Mainland China is too often mythologised as the “real” China, Hong Kong can be seen as a kind of Chinese diasporic centre for cultural reformulation, being a hybrid of East and West, as well as one of the world’s largest production centres for films, comparable to Hollywood and Bombay (Mumbai). The Chinese communities of Asia, Australia, Europe and North America form a “geolinguistic region”, or worldwide audience for the Hong Kong film industry. Its hybrid cinematic aesthetics fuses different genres and creates a syncretism analogous to the constitution of hybrid personal identities. Its narrative preoccupations, particularly prior to 1997, which centred on such postcolonial themes as exile, displacement and migration, offer their own kind of ethnography of the Chinese diaspora, and resonate with the diasporic sensibilities of loss, deterritorialisation and incorporation. Clara Law’s Floating Life (1996), the first-ever foreign-language film to be made in Australia, provides an excellent illustration of such narratives of displacement, not unlike the stories of some of the respondents who participated in this research.

In Australia, in the name of an immigration and settlement policy which aims to protect the rights of immigrants to keep their cultural differences, the official discourse of multiculturalism ironically almost obliges them not just to “have” a culture, which they come with, but furthermore to maintain it. This rhetoric valorises an essentialist concept of “culture”, largely manifest as language, food and ritual. Whereas the Chinese of the Southeast Asian and Indochinese countries are accustomed to living in societies which, while not necessarily tolerant and harmonious, at least give them some experience of cultural pluralism and sense of difference, this is not true for the Taiwanese, nor for the Mainlanders. Thus, apart from the likelihood that these latter groups have not been prepared by their culture of origin to know how to respond to the “discovery” of their own racial and cultural difference, Australian officialdom, even as a benevolent host, can also make them acutely aware of their “Chineseness”. Furthermore, since 1996, having to bear the role of Chinese subject ascribed by the official though benign discourse of multiculturalism has been given a darker side, to the extent that all Asian ethnicities have been very publicly racialised by the notorious Pauline Hanson and her One Nation party.

In the context of international power relations, Taiwanese Chinese now resident in Australia have their own reasons again for relating to the host society and the media in a state of awareness of their Chinese ethnicity. The public political culture of Taiwan, in which Taiwan is set off ideologically against the PRC and the Communist Party as the sanctuary and the guardian of Chinese culture, arguably leads to Taiwanese migrants carrying with them an already acute, if overdetermined, sense of Chineseness as a dutiful burden. Thus, due to both their characteristic collective historical experience and the shifting features of the new social environment with which they must deal, they are likely to continue to occupy the position of “Chinese subject”, much as they would have done in Taiwan. In the case of the Mainland Chinese, by contrast, few of them leaving China in recent years are likely to have identified themselves with the position of “Chinese subject” as promoted by the government of the PRC, being rather more influenced by the “leave-the-country fever” (chuguore) prevalent after Tiananmen (Yang, 1997: 305).

Narrowcast Institutions: SBS and New World

Broadcast television in Australia is a mixed system, with a private sector comprising three national commercial networks (Channels 7, 9 and 10), while the Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC) provides its national network out of public funds, and the Special Broadcasting Service (SBS) delivers a “multicultural” service to the main population centres, funded by a combination of sponsorship and government allocation. Within its wide range of foreign-language news and entertainment programming, SBS provides daily news services in Chinese (both Mandarin and Cantonese), and screens occasional films from the nations of Greater China. In addition, there are low-power “community” channels in Sydney and Melbourne, where the Asian Community TV program is broadcast, having been prepared by volunteers from the Asian communities.

As well as programs, cultural products such as television services attest to the formation of transnational networks of media circulation and (re)production between “home” and “host” sites, the technological means for cultural maintenance and negotiation. In this context, new services such as New World TV, an Australian Chinese-language subscription television channel, can be regarded as a form of specifically diasporic television because the “global Chinese” of Melbourne and Sydney are targeted as the sole audience for this kind of “narrowcast” service. Both SBS and New World were therefore of great interest to this study from the viewpoint of their sources of programming and its timeliness, relative to the countries of origin.

Within the diverse complex of media used by Chinese viewers in Australia, narrowcast television services have a special place. While broadcasting is driven by the logic of maximising audiences across difference, by the production of an abstracted “mass”, narrowcasting fragments the audience using niche media targeted at minority publics or markets. While broadcasting generally denies difference, narrowcasting exploits it, often fetishising a notion of a singular or “special” identity determined by a fundamental essence: ethnicity, race, sexuality or whatever. There are, of course, other forms of narrowcasting which service various taste markets or restricted localities, but for diasporic Chinese viewers in Australia, it is those television services that speak directly to their Chineseness—that invite various forms of diasporic identification—which are the most significant. As the marketing slogan for New World TV, a Chinese-language subscription channel, used to declare: “Intimacy is to speak your language.”

For Naficy (1993), narrowcasting remains an under-appreciated discourse. He argues that the processes at work in the specialisation and fragmentation of television demand more thorough attention. This is not simply because these developments are important evidence that the media imperialist and global homogenisation theorists are wrong, but also because ethnic narrowcasting is a manifestation of the emergence of new media sites that address the experience of hybridity, migration and diaspora, speaking to the disruptive spaces of postcolonialism. Narrowcast media, then, provide one example of a growing third or multiple cultural space where various “othered” populations are creating sites for representation, where all kinds of “resistive hybridities, syncretism and mongrelizations are possible, valued” (Naficy and Gabriel, 1993: x). Implicit in this valuation is a fundamental opposition between broadcasting as the heartland of nation and family, and narrowcasting as the space of the migrant, the exile, the refugee. But the space of narrowcasting is not simply a space of representation: it is also a space of consumption, a space where otherness circulates as a commodity. How, then, should the distinctive cultural economies and topographies of desire shaping narrowcast television services for Chinese viewers in Australia be understood?

The crucial point, Naficy argues, is to recognise the various ways of being narrow, to understand the specific dynamics of inclusion and exclusion ordering minority media. This is the reason why two Chinese-language narrowcast services available in Australia have been investigated: in order to track patterns of similarity and difference in their institutional and cultural logics. By looking closely at the Chinese programming of SBS, Australia’s unique free-to-air (but advertising-supported) public-service multicultural channel, and at a cable subscription, or “pay TV”, channel—New World TV—it is possible to see the complexities and variety of narrowcast television.

The other reason for singling out these two services is that they provide the main source of audiovisual news for Chinese audiences in Australia. As many studies of the migrant experience have shown, news from or about “home” has special status and value. It is a privileged form, watched avidly and intently and often in a state of what Naficy (1993: 107) terms “epistephilic desire”. News generates strong demand: all services programming Chinese news in Australia report intense viewer requests for more, which confirms the strength of demand apparent across all groups in our household interviews, to be detailed later. So, in the maze of diverse textual forms available to Chinese audiences, news is distinctive not just in terms of the way that it is watched, but also in the symbolic value it holds as a source of direct access to and information about homelands. News generates very specific relations in space between here and there, because of the way it mediates the play of separation and connection in time, then and now. By contrast, in the absence of any referent in real space or time, purely fictional texts function quite differently in the kind of longing they work upon.

Thus, in focusing on these two services, SBS and New World TV, the intention is to examine the nature and meanings of their narrowcast organisation through the specific example of news. In this way, it will be possible to not only understand how news is implicated in particular forms of diasporic identification, but also how differently two narrowcasters use news to establish distinctive relations with Chinese viewers.

Special Broadcasting Service

SBS Television was established in 1980 with the mandate to be both multicultural and multipurpose. The channel has to service various special communities (ethnic, indigenous, minority), reflect multiculturalism to all Australians, and increase diversity in the broadcasting system. As a public service broadcaster, SBS is unique in the world. Established as a key institution of multicultural social policy, it is charged with the dual tasks of representing and maintaining different identities and adding quality and innovation to the Australian television landscape. The complexity of SBS’s mixture of objectives adds up to a bizarre and pleasurable heterogeneity. To scan its program guide on a given day is to encounter a strange collection. For example, one evening during the research period included the previous night’s news bulletin from Beijing in unsubtitled Mandarin; the OUT Show (a local gay issues program then current); a studio debate about cultural diversity in Australia; an avant garde animated film; and a movie from Turkey. This heterogeneity means that SBS has several different logics of narrowcasting at work within the one service, unlike exilic TV or other single-purpose niche TV services.

At the simplest level, SBS is a narrowcaster because it imagines the nation as a series of fragments, a multiplicity of constituencies produced through various axes of difference—often those very differences that broadcasters are unable to see in their obsession with maximising audiences. In fragmenting the nation, SBS also recognises its members’ connections with other places, and acknowledges identities constituted through relations of movement and longing across national boundaries. Programs in languages other than English, programs imported from outside the dominant Anglo-American nexus, implicitly disrupt narratives of national cohesion. Most significant here is the example of WorldWatch, SBS’s morning news service, which broadcasts satellite-delivered national news bulletins from around the world.

WorldWatch began on SBS in 1993 with screenings from 6.30 a.m. onwards of daily news services from CCTV (China Central Television) Beijing in Mandarin; France 2 Paris; Deutsche Welle Berlin; the Russian News, Vreyma; and two current affairs programs from public broadcasting stations in the United States. These services were generally picked up the night before by various satellites to which SBS had access, taped and then broadcast unsubtitled the following morning. Access rights were free, so the cost of the services has been negligible, while allowing SBS to assume a role in providing timely news to an impressive variety of niche audiences. Since its inception, WorldWatch has steadily increased its representation of nightly news or weekly current affairs magazines to include bulletins from Italy, Indonesia, Japan, Hong Kong, Lebanon, Spain, Hungary, Chile, Poland, Greece and the Ukraine.

The significance of WorldWatch on SBS is that it is evidence of its capacity to establish a particularist or minority stance within a broader multicultural framework. While most non-English shows on SBS are subtitled in the interests of national access, in not subtitling WorldWatch (a decision predicated on cost and time pressures), SBS addresses migrant and diasporic audiences without symbolically “assimilating” them into the nation. However, the absence of subtitles also means these bulletins are subtly marginalised within the overall institutional politics of the network, in that SBS remains primarily a broadcaster, albeit of a very particular kind. Thus prime time is the privilege of multicultural programming accessible to all, rather than minority or narrowcast programming.

SBS’s CCTV4 news in Mandarin is one of its most controversial services, generating a significant number of letters and phone calls protesting that the service is nothing more than a propaganda exercise. Once again, this is consistent with the train of comments made about it in the household study, to be presented later in this chapter. CCTV is Mainland China’s national broadcaster, and Channel 4 is its international service, aimed at diasporic audiences and able to reach almost every part of the globe.

CCTV4 leases satellite capacity around the world, and SBS has an agreement with it to access the service without charge via the PanAmSat private satellite network. SBS’s only costs are infrastructural, as a dedicated downlink and encoder are necessary to pick up PanAmSat. Beijing authorises SBS’s use of this service through a special code and pin number, although this authorisation is never completely assured. For example, SBS has wanted to develop a Taiwanese service on WorldWatch, but fears that Beijing may revoke its licence to CCTV4. SBS initially picked up CCTV4 via the Russian satellite, but the service is now more sophisticated and has moved to PanAmSat which has far wider reach and digital transmission. CCTV4’s 9.00 p.m. (China time) news, which SBS picks up at midnight, tapes and screens at 7.55 a.m. the next morning, is more outward looking than its 7.00 p.m. service. It has shorter domestic stories and a slight orientation towards international issues.

Screening directly before CCTV4 on WorldWatch is Hong Kong News, aimed at balancing the Mandarin service with a Cantonese one coming from outside the Mainland. Hong Kong News was picked up as a direct result of community demand, and helps SBS avoid accusations of bias or special privileging of one section of the Chinese audience over another. These sorts of delicate negotiations and accommodations are not peculiar to SBS’s Chinese programming, but occur across many different languages. They reveal the difficulties in assuming any sort of coherence within categories like “Chinese viewers” or “the Chinese community”. They also reveal the potential within narrowcast services to fragment audiences into ever more specific niches.

Hong Kong News comes from Asia Television Limited (ATV), one of the two commercial free-to-air broadcasters in Hong Kong that provide programs domestically in Cantonese, Mandarin and English. The Cantonese language bulletin on SBS is primarily produced for audiences in the United States. It is commissioned from narrowcast channels in the United States and Canada, and compiled using large segments of content from the ATV domestic news bulletin for Hong Kong. As the satellite signal from Hong Kong is available only on a hemispheric northeast beam to northern America, the SBS pictures travel to the west coast of the United States first before being re-routed via the same satellite to Sydney.

The significance of the Chinese and other non-English language news services on WorldWatch is that they represent a very unique and innovative form of public service narrowcasting within the overall context of a multicultural free-to-air channel. While SBS is without question a niche service, its political rationality has historically favoured rhetorics of access and tolerance in the name of serving “all Australians”. This has been evident in the symbolic economy of English subtitling, which has functioned to make all shows in whatever language accessible in the interests of national coherence and the promotion of intercultural understanding and tolerance. Yet, by switching on WorldWatch in the morning, the monolingual English speaker can have the interesting experience of exclusion—of confronting what Benedict Anderson (1983) aptly describes as the vast privacy of language. In this moment, non-subtitled Chinese and other news services disrupt the hegemony of the singular national language; they manifest a form of narrowcasting that is militantly particularist, and that implicitly contests multicultural rhetorics of national unity across difference. The absence of subtitles on WorldWatch could mean forms of identification unmediated by the obligations of multiculturalism, diversity without access and difference without nation. Perhaps it even prefigures a new form of postnationalist or even postmodern public service television.

New World TV

The example of SBS is extraordinary because of its singularity. Here is a free-to-air public service channel offering an impressively diverse array of narrowcast programming from avant garde video for yuppie taste markets to unsubtitled news bulletins for diasporic, migrant and refugee communities. In contrast, pay TV operates within a quite different set of cultural and economic dynamics. For a start, it is fundamentally demand-driven in its relationship with the subscriber base. This means that it is not necessarily committed to increasing media diversity: more channels does not mean more variety or difference in program types or sources. Pay services still tend to be driven by competition for big audiences, hence the favouring of mass-appeal shows. The genuinely narrowcast channels that pay does offer exist on the margins, and there remains a certain reluctance to provide them, on the assumption that so much television viewing still seems to be habitual rather than discriminating. There is obviously a fear that too much targeting of niche audiences could undermine the search for a big and therefore broad subscriber base.

Narrowcast channels on Pay are thus relatively scarce in Australia and exist as tiered add-ons to subscription packages. This was notably the case with New World TV (NWTV), a Chinese-language channel available to subscribers of Australis Media’s Galaxy pay TV service for an additional monthly fee. NWTV began transmission in Sydney and Melbourne in 1994. By 1998, when the service ceased with the collapse of the Australis Media company, it was transmitting 24 hours a day to all capital cities except Hobart and Darwin, using a mixture of MDS and satellite. Programming was put together in Sydney, nearly all of it being imported from three main sources: Television Broadcasts International (TVBI) which offered satellite news, variety, movies and specials in Cantonese; Chinese Television Network (CTN), also from Hong Kong, but in Mandarin, with two channels, one on news and finance updates (the Chinese version of CNN), the other focusing on lifestyle and infotainment; and Television Broadcasts Superchannel-Newsnet (TVBS-N), a popular cable channel from Taiwan in Mandarin. A small minority of drama and documentary programs came from Radio Television Hong Kong (RTHK), the government-owned service in Hong Kong. There was negligible “local”—or, more specifically, Australian-made—content on New World TV: only around ten minutes per week.

The sources of programming reveal the strong links which NWTV had with Hong Kong, the centre of Chinese languages audiovisual production and export. They also show the sense in which NWTV could be classified as a form of diasporic narrowcasting. This almost complete reliance on imported content is a product of economic and policy factors. Australian pay TV regulations do not demand local content on narrowcast or non-drama channels. In contrast, Canada has foreign content rulings on pay which mean that 40 per cent of programming on Chinese channels has to be locally produced. There were no such obligations on NWTV and this had significant implications for the overall feel of the channel, for its sense of place—or perhaps placelessness. Studies of free-to-air broadcasting have noted the crucial role of links, station identifications and promos in generating a sense of audience loyalty and identity that is place-based. These televisual forms work to localise the channel even though it may be part of a network. This strategy was not crucial to the operations of NWTV, which had a constantly shifting array of links, modes of address and promos in which the local was absolutely marginal. Viewers were rarely addressed as members of an imagined community known as the “Australian Chinese”, linked by their common location in Australia and common pleasure in NWTV. Instead, they were internally fragmented with a service that spoke to diverse forms of Chineseness and diverse senses of homeland.

If there was any location that did give NWTV some sense of place, it is Hong Kong. Most of the news, financial reports, forums and movies came from there, as well as the very distinctive and popular soaps. This Hong Kong-centrism reflects its history of long-established dominance in media production, and the way in which Hong Kong has come to stand for what could be described as an Asian version of Hollywood. For not only do Hong Kong media companies engage in aggressive distribution to Chinese markets overseas, but they have also been central in providing the spaces where narrations of East–West relations are negotiated. Hong Kong stands as a key signifier in this relation, the New York of the East: the site of consumerism and upward mobility. Hong Kong’s domination in media exports to Overseas Chinese is also linked to hierarchies of Chinese identities, and to the complex politics of inclusion and exclusion in Overseas Chinese communities, with Hong Kong Chinese having higher socioeconomic status and better social connections (guanxi) than, for example, Mainland or Vietnamese Chinese.

News services were a major component of NWTV’s schedule. Audience surveys conducted by the channel consistently revealed a strong demand for news. This was always rated as the most desired content, but this desire was qualified by demands for very particular types of news. CTN’s global orientation, its address to the “global Chinese”, was not valued nearly as much as local news bulletins from the homelands, synchronised as closely as possible with the country of origin. In order to satisfy this demand, NWTV was picking up the nightly news bulletin from TVBI in Cantonese on a satellite feed via PanAmSat2, taping it, then immediately screening it. Taking into account time differences, this meant that the TVBI news went to air at about 11.30 p.m. in Australia—too late for many viewers—so it was repeated at 7.00 a.m. the next morning. The only news service that was broadcast live—direct via PanAmSat2—was CTN’s Zhong Tian News Channel in Mandarin, which was basically used as filler between 1.30 and 6.30 a.m. TVBS-N’s midday news from Taiwan in Mandarin was fed to Hong Kong for satellite re-broadcast internationally. It was going to air on NWTV at 4.35 p.m. on the same day.

With the demise of the Australis service in 1998, Optus Vision was left with the only available pay channel in Chinese. This effectively is no more than a package of the Hong Kong CTN feed formerly seen on NWTV, and the Mainland CCTV service, already available free-to-air on SBS, as previously discussed. The pay market leader, Foxtel, has not sought to fill the vacuum created by NWTV’s disappearance, suggesting that the complexities of providing a satisfactory range of programming for the substantial but diverse communities of Chinese in Australia do not warrant the returns to be gained, particularly where there are free-to-air programs on SBS.

Yesterday’s News

Indeed, the variety of Chinese news programs available on SBS’s WorldWatch and formerly on NWTV provides evidence not only of the diversity of viewers, but also of the special status news holds for diasporic communities. While other genres such as movies or soaps may be enjoyed by Chinese audiences from different backgrounds and countries of origin, news does not generally function in this way. Naficy’s (1993) account of epistephilic desire reveals the intensity of longing for specific information about “home”—the desire for immediate, simultaneous access to knowledge about “there”. Domestic news bulletins from countries of origin are the key form sought out to satisfy this longing. This very distinctive use of news shows how crucial this genre is—probably more so than any other—in mediating senses of liminality, and in providing a space where the movement of separation and connection, of ambivalent and unstable points of personal and national identification, are negotiated.

There are several reasons why news occupies this role beyond the obvious fact that it is a major source of information and national imagining. Studies of the relationship between television and everyday life point to the central role of news bulletins in ordering the lived experience of time. For Paddy Scannell (1996), the structuring principle of broadcasting is “dailiness”: the processes through which radio and TV retemporalise time via institutional regimes like the schedule and audience viewing rituals that are shaped in relation to this. News is crucial in this process because of its location in the schedule as a marker of each day passing and because of its textual principle of liveness, of specifying what is going on rather than what has been, what marks the particularity of this day. Broadcast television news, then, is central to how senses of home and the everyday are both ritualised and temporalised.

What then of news bulletins on narrowcast media, screened out of the context of a national television service, and in a different time zone and frame? How are these experienced by viewers? Chinese audiences for SBS and NWTV watch yesterday’s news. They wake in the morning and switch on last night’s bulletin from Hong Kong, Beijing or Taipei. These minority audiences access evening news from home (with all the temporal effects that are associated with news as a summation of the nation’s day) the following morning. This temporal dislocation may appear insignificant. After all, narrowcast television channels are still satisfying the fundamental desire for access to homeland news services. There can be no doubt that, for these audiences, narrowcast news generates a double imaginary of time, a sense of being in two temporalities: here and there, then and now. Scannell’s argument about dailiness applies more to the national rhetorics of broadcasting. In the cultural and economic logics of global narrowcasting, the schedule has a quite different function and generates correspondingly different audience rituals and temporalities. In interviews, Chinese viewers of these news services described how they delayed going to work in the morning in order to find out what happened at “home” yesterday. They needed this information, this sense of ritualised summation of the day over there, even if it was experienced in another place and another temporal order.

One Taiwanese family interviewed had a distinctive set of news-viewing practices. This family subscribed to NWTV because of the mother’s strong desire for access to the TVBS-N news service, which she had watched daily in Taiwan. News was the main form of content that the family watched on NWTV. The father watched the TVBI service in the mornings on a semi-regular basis for business reasons, but he had problems with the incomplete subtitles because it was in Cantonese, and he also found its Hong Kong-centrism very frustrating. His preference was for news in Mandarin, and found subtitles a major disincentive on television news, so often preferred to read a newspaper. It was a similar story for the two daughters still living at home in this family. They occasionally watched CTN’s lifestyle channel, Dadi, for gossip about the Hong Kong film and pop industry, but generally were not home during the day for the TVBS-N service direct from Taiwan.

The most avid news watcher was the mother, who watched TVBS-N daily. A significant value of this service to her was that it was being screened close to real time in Taiwan. This is the same service that she and the father used to watch in Taiwan over lunch, and now could watch in Melbourne later in the afternoon. For the mother, this service generated intense epistephilic pleasure, not just because it provided information, but because it was a domestic service, not one re-edited for an international market. It provided a strong sense of temporal and spatial connection with home—as she said herself, it made her feel “very close to home”. This was definitely not yesterday’s news, unlike all the other news services that were then available on NWTV. It could be argued that, with this service, the mother was able to maintain a sense of dual dailiness, a doubling of time that allowed her to remain connected to experiences of everdayness, both here and there.

Also of interest were the family news-viewing rituals in this household. Every evening over dinner, everyone watched the ABC news. The daughters often had to translate, but there was generally a lot of discussion, especially about the ABC’s coverage of Taiwan. This repeated a domestic practice from Taiwan, where the family would watch the government news at 7.00 p.m. daily. Here, too, is another sense of dailiness produced through the maintenance of a ritual, and the ways in which evening news bulletins are incorporated into family interaction. ABC news is of a quite different order textually, and was much more connected to the family’s sense of location in Australia. For the daughters especially, knowing about “here” was highly valued. These complex and various patterns of news viewing are, of course, open to disruption. When there is a major event in Taiwan or elsewhere in Greater China, every available news service is devoured, such as was the case with the events of Tiananmen Square. Significant events generate another sort of temporality that disrupts the sense of a daily summation or a never-ending flow of information, as they have a quite distinct temporal existence and duration.

Uses of narrowcast news services by Chinese audiences in Australia are complex in that they are intricately connected to questions of time, to the relation between the distinctive temporalities of televisual news which privilege presentness—the live—and a ritualised marking of the immediacy of each day—the phenomenological time of viewers. The mother’s use of the TVBS-N service, which explicitly was not a global news service structured around a 24-hour flow of never-ending information, but a national domestic service structured around the daily ordering of information and events marking the particularity of each day in Taiwan, raises interesting questions about the significance of the temporal and the pleasures of double time for such diasporic viewers.

Distribution of Chinese-language Video and Film in Australia

In order to bring to light the circulation flows and distribution circuits of non-broadcast media products (film as well as video) which connect the countries of origin of such material with their diasporic markets in Australia, the audiovisual media consumption of diasporic audiences in Melbourne was investigated through a series of interviews with video store traders and a film distributor. More particularly, the purpose of interviewing video store traders was to obtain inside information and opinion on the organisation of the Chinese video business, including the relationship of video store owners to the distributors; and to collect the traders’ observations of the characteristics of the market for Chinese videos: its dynamics, its demographics and any segmentation it might exhibit. As well, information was obtained on the Chinese cinema circuit, and the integration of cinema exhibition and video distribution, using both interviews with individuals involved and printed material from business and trade journals, and from secondary sources.

While videos from their home or culturally proximate countries are an important medium for diasporic viewers, it should be appreciated that they do not rely necessarily or exclusively on commercial distribution through video stores as a source of their videos. Some of the respondents in the household interviews did not rent videos from local stores at all, but did watch them occasionally when tapes were circulated amongst their informal kinship or other social networks. Videos are constantly brought into Australia by diasporic viewers themselves—some of whom are frequent travellers, as we have seen—or by visitors from their home countries, and then passed throughout such networks.

Furthermore, videos and other audiovisual products such as karaoke tapes are not just imported in a single, direct flow from the home country to Australia. Sometimes, they are involved in a lateral distribution circuit—for example, Hong Kong videos might first circulate in other parts of the Chinese-speaking world, such as Singapore, Malaysia or China, before being brought to Australia. In other words, some of our household respondents in Australia, particularly Southeast Asian ones, would have acquired Hong Kong tapes from such other countries, but not so much from Hong Kong. In some instances—especially when the tapes are acquired in Singapore—the original Cantonese vernacular is dubbed into Mandarin: in Singapore, Hong Kong material in Cantonese is not allowed to be distributed, so it is all dubbed into Mandarin.

In fact, this language difference—Cantonese being the language of Hong Kong and Mandarin of Mainland China and Taiwan—turned out to be a decisive determinant in the structure of the video business. The Mainland Chinese and Hong Kong video industries effectively run in parallel, each with its separate producers, distributors, rental outlets and customers, with very little crossing over to the other side. This is for linguistic rather than business or political reasons. Thus, because Taiwanese videos—like those from the Mainland—are in Mandarin, they are also available in stores which rent Mainland videos. The subtitling of Hong Kong as against Mainland Chinese and Taiwanese videos does allow for some crossing over, since the written language is much the same.

Videos of cinema releases carry subtitles in Chinese characters, so that Chinese who do not speak Mandarin can follow a Mainland or Taiwanese film, and Chinese who do not speak Cantonese can follow a Hong Kong film. Some film studios, certainly those in Hong Kong, also give English subtitles to their cinema releases. However, it is interesting to note that television series and variety programs produced for domestic viewers in Hong Kong, China or Taiwan, and then marketed as videos, are not subtitled—the expectation being that television product is less tradeable across national borders within the Chinese-speaking world than is film.

Distribution Circuits

Apart from its geopolitical position on the threshold to the “motherland” of China, its central location within the networks of Overseas Chinese, and its mythical status as the metropolis and global disseminator of Chinese popular culture, Hong Kong is in fact prominent in television production and distribution in Asia, based on its older pre-eminence in cinema production and export. Television production is based on the two networks which dominate the domestic market, TVB and ATV.

TVB (Television Broadcasts) is controlled by Sir Run Run Shaw and the Malaysian-Chinese entrepreneur Robert Kuok. Through its international arm, TVBI, it exports most of its domestic production—around 5000 hours annually—in various forms and in several languages, but principally to diasporic markets. As well as having its own video outlets in Southeast Asian countries such as Malaysia, it also has cable subsidiaries in the United States and Canada, and a satellite superstation aimed mainly at Taiwan, TVBS. These are its major overseas markets, from which it was deriving over 15 per cent of its income by 1995 (Chan, 1996; Langdale, 1997; Lovelock, 1995; To and Lau, 1995).

As well as its vertical integration of television production and distribution on an international scale, TVB is horizontally integrated with Shaw Brothers (Hong Kong) Limited, a major distributor of cinema (Lent, 1990). After these, the next largest companies in Hong Kong active in media exports to diasporic and other overseas markets are built on similar vertically integrated models to TVB and Shaw Brothers, but are not related. These are the television network ATV and Golden Harvest, which is a major exhibitor as well as producer and distributor of films, well known in the West through one of its principals, Jackie Chan (“Hong Kong Films Conquer the World”, 1997). In 1998, it was announced that Golden Harvest would issue shares to Rupert Murdoch’s News Corporation, as well as to Robert Kuok and the Hong Kong communications entrepreneur Li Ka-Shing. Also at that time, Australian cinema distribution and exhibition company Village Roadshow had more than a 16 per cent share in Golden Harvest, and a joint venture with it in building cinemas in Southeast Asia (Mathieson, 1998).

As for Mainland China, television production and distribution—both for the domestic and international markets—is centralised under CCTV (China Central Television), which commenced a global service for the Chinese diaspora in 1995 (Langdale, 1997: 315). There are also significant provincial and municipal stations in Shanghai, Guandong and Sichuan. According to Chan (1996), all of these are active in program exports, both in their own right and coordinated through the export agency CTU (China Television United). Films are marketed overseas through the Beijing Film Export Corporation. Thus Mainland China, as well as Hong Kong, is active in pursuit of audiences of diasporic Chinese.

Our research in Australia has found that there are direct links between the many small neighbourhood Chinese video stores and the major distribution corporations of both Hong Kong and Mainland China. These same global distributors also supply films to the specialist Chinese and cult cinema circuits, as well as the narrowcast broadcast television services which have been mentioned, evidencing how the patterns of horizontal and vertical integration in which they structure themselves in their domestic markets also extend out into their diasporic markets.

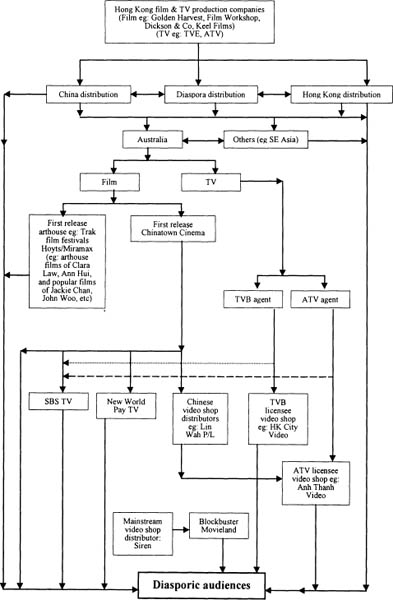

Figure 2.1: Flowchart of distribution of Hong Kong film, TV and video in Melbourne

To take video stores first, our research discovered that, in line with the market segmentation by language noted above, a video store would stock either Mainland Chinese videos in Mandarin (most are CCTV serials, in fact), or would be tied to one or the other of the two Hong Kong major distributors by licence agreement, and so stock either ATV or TVB Cantonese product.

Although traders in both kinds of store were suspicious of the project and gave evasive or reluctant answers, we were able to establish that the Hong Kong video stores in Melbourne sign contracts with TVB or ATV, but not both: each distributor requires that a store deal with it exclusively. The contract with the distributor typically runs for a year, and can cost at least $100 000. In exchange for this fee, the trader has access to TVB or ATV’s entire past and present stock, which includes movies and all television genres, for the term of the contract, which may then be renewed with another fee. However, video store owners cannot choose from catalogues, but must take what the distributor offers—a practice obviously advantageous to the distributor, particularly where distribution is vertically integrated with production. The trader is always given only one master copy, but authorised by the contract to make as many copies as necessary from his or her own blank tapes.

The Mainland Chinese side is organised on principles that generally follow the Hong Kong pattern. To quote one video store manager in an inner suburb: “There’s a distributor in Melbourne. We sign a contract with a distributor each year who deals with all the Chinese state-owned TV serial producers. We give the distributors their fee each year and they give us a package. We can’t choose.” This store dealt only with the one distributor. Another trader named a distributor in Sydney, Tangfeng, and said he dealt only with them.

While the Hong Kong stores are tied to either TVB or ATV, some do stock videos from other sources as well. For example, Anh Thanh Video is one of the biggest Chinese video chains in Melbourne. It has shops in the City (Chinatown Midcity Arcade), and those suburbs which have an above-average proportion of people of Chinese descent, namely Richmond, Footscray, Springvale and Box Hill. Anh Thanh Video stocks not only ATV programs and shows (including game shows, infotainment, music and variety shows, television serials and news), but also a similar range of Mainland Chinese Mandarin-language programs and shows; popular Japanese material (such as television serials, mangas, music and variety shows); and popular Taiwanese television programs, serials and shows in the hybrid dialect Minnanhua. Anh Thanh Video is exceptional in that it has a “parent” company called Lin Wah P/L with which it shares premises and a phone number. Lin Wah P/L is the licensee and main distributor of Chinatown Cinema videos to Chinese video stores in Melbourne, distributing Chinatown Cinema movie videos to both Anh Thanh and Hong Kong City TVB Video.

Chinese video shops are organised differently from mainstream video shops. Usually, there is a counter in the front of the shop, on which are several clear folders and photo albums of movie posters, surrounded by walls that are covered with handwritten lists, and more movie posters. Customers make their selection from the lists, posters, clear folders and photo albums, rather than browsing around and picking up copies of empty tape covers like in the mainstream chain outlets such as Blockbuster and Movieland. More often than not, customers will have already heard of the video they are after before going to the video shop. The trader usually charges customers about $30 (refundable) for membership, which entitles them to rent tapes which cost from $2 (old releases) to between $4 and $5 (new releases). There are no specific overnight loans because the number of days that one is allowed to keep the tapes is dependent on the number of tapes borrowed. For example, if a customer rents seven tapes, they are returnable in seven days’ time.

From this system, it follows that traders will usually want to make numerous copies of latest releases, as customers are allowed to keep them for over a week—hence more copies to accommodate slower turnover. Also, there is an incentive to re-record new titles over tapes of old ones when their popularity ebbs, so our questions about which types of videos did the traders find were in higher demand and which they had the least stock of were irrelevant, because if traders found that they had higher demand for a particular tape, they would simply make more copies, and when their popularity faded, they would recycle the tapes for the next blitz of popular new releases. This practice is one reason for the extremely poor quality of the tapes, a matter on which most respondents in the household interview study made comment.

In these circumstances, piracy might become an issue, concerning whether or not the store owner has continued to copy and rent out videos once the term of the contract that covered them is over, and the broader issue of whether or not the film or television producer’s copyright has been infringed by the contract between the distributor and the video shop. Because, under the terms of the Berne Convention, action against infringement of copyright must be initiated by the possessor of the copyright, the copying of Hong Kong videos in Australia passes without attention from the film and television producers in Hong Kong, who neither need to nor wish to spend money and time on small claims in Australia, and who, for the bulk of the content available, are also vertically integrated with the distributors in any case.

China is not a signatory to the Berne Convention, but piracy in the Mainland sector is alleged to come about through unauthorised taping of Chinese television programs in China directly from broadcast television, then exporting them. It was not possible to tell from looking at the tapes on the shelves in the three Mainland Chinese video shops visited whether they had been released under licence by CCTV or not. Some were in sleeves with printed titles, indicating a master tape released to the trader under licence, but most were in sleeves with handwritten titles. This meant that they could have been pirate tapes, or they could have been copies that the trader was authorised to make from the distributor’s master tape under contract.

Cinema

Chinese-speakers in Melbourne can see first-release Cantonese-language Hong Kong films at the Chinatown Cineplex on Bourke Street, part of a national chain owned by Winston Leung. Tickets cost approximately $8 for a double-feature, one being a first-release main feature; the other usually a re-run. These are the popular films many diasporic viewers would watch in their “home” countries, and those able to travel back there for business or to visit do also watch such films when they have the opportunity.

There are also alternative arthouse cinema and film festival or other special-event circuits which screen films from auteur Chinese directors like Clara Law and Wong Kar-wai, films which the Chinatown distribution circuit will not show—at least unless they prove popular on one of the other circuits. Chinatown’s resistance can be attributed in part to the international (that is, non-Hong Kong-tied) nature of their funding, production and distribution, as well as to the off-beat character of the films themselves (that is, commercially risky compared with proven genres).

For example, Clara Law’s Autumn Moon (1992) was a Hong Kong film, but partly funded by a Japanese consortium. It was released in Cannes and picked up by the film festival circuit, and then distributed via the arthouse cinema circuit. Wong Kar-wai’s masterpiece Fallen Angels (1996) was not circulated via Chinatown Cinemas and its video outlets, but released in Melbourne and other capitals via the national arthouse group Palace Cinemas’ Cine7 event.

It is interesting to note the cultural and commercial exchange which occurs between the arthouse and the Chinatown circuits over these Chinese auteurs. Because they are acclaimed and “approved” by international arthouse audiences, their most recent films tend to bypass the Chinatown circuit altogether, and go straight into the arthouse/film festival circuits. The response to this is for Chinatown then to screen their earlier films as popular cult reruns. A similar process occurs with films which fail with Chinese audiences but go on to enjoy international critical acclaim in the “West”. Sex and Zen, Naked Killer and The East is Red are good examples of films that enjoyed very successful queer or film festival screenings, were picked up by the international arthouse circuit, and only then were screened by Chinatown.

Finally—at least over the last few years—there is the mainstream distribution circuit, in which the West has become infatuated with the kinaesthetic martial arts comedy style of Jackie Chan. Of late, most of his films have been repackaged and re-released in the West via mainstream cinemas and cult-fanboy specialist venues. In Melbourne, for example, Rumble in the Bronx (when bought, repackaged and re-released by the multinational consortium, Miramax) was released (dubbed in English) through the mainstream national chain Hoyts in 1996. John Woo is another example. Having migrated to the United States from Hong Kong and become involved in joint productions with American companies, Woo’s first American-produced film, Broken Arrow, was also released via the national chains in 1996, soon to be followed by his Face Off.

As a footnote, it is interesting to note that some films enjoy laserdisc release status before they are released even in Chinese cinemas overseas. Some interview respondents affirmed this when they revealed that they had already seen some Chinatown movies from laser-discs that they had rented. The researchers’ experience is that traders sometimes do pass the latest not-yet-released films, such as Fallen Angels, over the counter to their customers.

From Chinese Cinema to Mainstream Video

Since about 1995, local video stores in Melbourne belonging to the major English-language chains, notably Movieland and Blockbuster, have been stocking a regular supply of popular Hong Kong films. It transpires that a local company, Siren Entertainment, has purchased a licence from Winston Leung, the owner of Australia’s Chinatown Cinema chains, to become the official distributor of Chinatown cinema movies to mainstream video stores. Siren gets rights to distribute a film on video only after its initial release through Chinatown Cinema (which holds the rights for the first twelve months), and then its video distribution to the Chinese-language stores, namely through Chinatown’s licensee, Lin Wah P/L (which holds joint rights with Chinatown Cinema for the next twelve months).

The recent success of particular Chinese films with mainstream audiences—both cult/arthouse and popular—and the advent of Chinese videos in mainstream stores would seem to demonstrate that appreciation of Chinese culture is not restricted to the Chinese and their descendants. Rather, it becomes diffused into the host society, and appears particularly attractive to those whom we could call, without prejudice, “cosmopolitan”. That is, Chinese media products, if made accessible to non-Chinese-speakers via dubbing or subtitling, can appeal not just to “communities of difference”, but also to “communities of taste” (Hawkins, 1996b). Second-generation Chinese, for their part, respond to these products in the context of whatever assimilation they would have received into the mainstream culture, so their media experience is hybrid, or “cross-cultural” in the best sense.

Results of Household Interviews (Survey Phase)

A household study was chosen as the best means by which researchers could speak to respondents in the “natural” setting in which they made use of the audiovisual products and services to which they had access, and because the household as a site for this kind of predominantly qualitative research has become so thoroughly theorised in the literature (Gillespie, 1995; Morley, 1992; Silverstone et al., 1992). In particular, a theoretical linkage has been established between the micro world of the household and the macro context of institutional structure, conceived at both levels in terms of space and time (Giddens, 1979). As well, a range of available research techniques has been developed around such an “ethnographic” approach, and its focus on the household setting (Silverstone et al., 1991; Sinclair, 1992).

The purpose of using such a household-based ethnographic methodology is:

to understand relationships in space and time: relationships with the physical geography of the home . . . relationships to the networks of friends and kin (which extend and transform the boundaries of the household beyond the physical); relationships with the past and with the future, in the appropriation of images and identities and in the expression of hopes and fears (Silverstone et al., 1991: 206).

There were two phases of household study. First, semi-structured family interviews were carried out with a constructed sample of households in which all the major Chinese-origin groups were equally represented. Then, in contrast to such a relatively broad-based survey approach, more truly ethnographic follow-up visits were made to the small number of households that were willing to provide the considerable level of cooperation which such research requires. For brevity, these will be referred to as the survey phase and the ethnographic phase. Taken together, they provide both an overview of media usage as found in selected sectors of Melbourne’s Chinese-origin population, as well as a more closely observed account of how media are integrated into the lives of specific households.

A target sample of 50 households was decided upon, composed of a quota of ten households for each of the five major Chinese-origin groupings in Australia: the People’s Republic of China, referred to here for brevity as Mainland China (MC); Southeast Asia, namely Indonesia, Malaysia and Singapore (SA); the Republic of China, better known as Taiwan (TW); Indochina, comprising Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos (VC); and Hong Kong (HK). Households were defined to include both unrelated adults living together as well as families and, as far as was possible, they were interviewed when all members could be at home together. Researchers were able to conduct the interviews in Mandarin, Cantonese, other dialects of Chinese, or whatever combination householders felt most comfortable with.

The semi-structured interview schedule used in this survey phase was designed for both adult and adolescent members of the household, asking them about their television viewing habits and preferences, though with particular attention to Chinese-related material. It also asked about their filmgoing and use of video, radio and other domestic information and communication consumer goods such as karaoke units and computers. Further questions were used to elicit socioeconomic status indicators such as occupation and education, as well as country of origin, citizenship and sense of cultural identity.

Mainstream Broadcast Television

When asked about the programs they regularly watched on television, there was quite a large number and wide range of programs mentioned, and without significant differences between groups, as Figure 2.2 shows. Programs in all genres were mentioned, from sport (the Atlanta Olympic Games were on during the period of some of the interviews, of particular interest to Mainland Chinese) as one might expect, to game shows, movies, series and serials, ranging from Australian soaps like Neighbours to thoroughly global programs such as The X-Files. News and current affairs programs of all types received frequent mention.

Figure 2.2: Number of English-language television programs named (all types)

Bearing in mind the sample size, the figures do suggest that the groups most fluent in English—those of Southeast Asian and Hong Kong origin—named slightly more programs in English. However, the number of times television programs in English were mentioned across the board by all survey respondents suggests that language is not so much of a barrier as might have been thought in watching mainstream television, even for the most recently arrived group: Chinese from the Mainland are every bit as likely to watch the news, or slightly less so a movie in English, as Chinese originating elsewhere.

Entertainment

On the other hand, the Mainland respondents’ remarks about their actual comprehension of television entertainment in English are illuminating, and suggest that television is often used as a means of access to mainstream language and culture. One (MC 9) said about The Oprah Winfrey Show: ‘The English is fairly familiar and informal, that’s why I’ve started to watch chat shows. I keep up with things watching them. I don’t watch regularly though.” That is, the accessibility of the English spoken on the show was a reason for this respondent to watch it, though she seemed aware that the program would be considered trivial by Anglo-Australians with her level of education.

Some of the Taiwanese respondents’ remarks about television (and about video and film) displayed a similar concern with comprehension, but also with informing themselves about culture—and in surprising ways. One 19-year-old Taiwanese respondent (TW 8) said about a national variety show, Hey! Hey! It’s Saturday, that: “It gives Australian news and humour. Trying to assimilate into Australian culture—that’s an indicator of how much you understand the language and the humour.” About Seinfeld, he said: “You watch and you learn quite a bit about Western culture, the way friends speak with each other sometimes.” Another respondent (TW 2) said, with a better sort of alibi: “Last month’s women’s group at La Trobe [University discussed] why Melrose Place attracts a female audience. Wanted to know why it’s so popular.”

The parochialism of news and current affairs on Melbourne television was a regular cause of complaint from respondents of all national origins. For example, regarding the Channel 9 news in particular, one Mainland respondent (MC 1) said: “News content not bad but pays more attention to British, Anglo-Celtic people.” A Cambodian-born respondent (VC 5) had a slightly more generous view of news: “They have very good news except that they are very limited, to Australian current affairs only. It would be better worldwide.” A Singapore-born respondent (HK 4) thought that: “In international news they’re very poor. Australia is very poor in terms of geographical and political awareness of the region.” A Hong Kong respondent (HK 5), asked whether there was enough coverage of events of concern to Chinese people on the Channel 7 news, said: “I wouldn’t say so. If I know something particularly is happening in China or Hong Kong, I will turn to the SBS news.” Similarly, a Mainland respondent (MC 4) said about the Channel 10 news: “The international news on Channels 7, 9 and 10 isn’t as good as on ABC or SBS. They [the commercial channels] have more Australian news.”

The ABC news fared a little better, though it did not escape criticism. A Malaysian-born respondent (SA 9) said: “[It] gives you more substance to the facts, more of a world view.” A Mainland respondent (MC 2) thought the ABC news was “All right. [It has] a bit more [on China] than the commercial channels. They have their own correspondent in Beijing.” An Indochinese respondent (VC 1) said it was: “Better [than the commercial channels], still mainstream, not analysis.” Asked if there was enough news on Chinese topics on the ABC, a Southeast Asian respondent (SA 5) said: “No. Slightly better than commercial news format. News is presented too short and snappy to get the full picture.”

The SBS news was best regarded for its international scope, but attracted different and sometimes contradictory charges of political selectivity. One Taiwanese respondent (TW 3) said it was “All right. Better than Channels 7, 9 and 10, because it’s broad in scope. The other channels have more Australian news.” A Southeast Asian respondent (SA 8) thought it was: “Very international. News mainly on Yugoslavian civil war lately but they had a comprehensive report on the flood situation in China. I prefer it to news focused on local content.”

However, while the global scope of the SBS news was valued, there were criticisms of the way in which news from China was framed. Another Southeast Asian (SA 5) said, with some theoretical knowledge: “Chineseness is constructed as other, exotic and different.” Yet another (SA 3) said it was: “Politically correct in Western terms—for example, the Dalai Lama; anti-Chinese, pro-Western standpoint.” A Taiwanese respondent (TW 8) said: “The materials they present are very selective. They try to avoid sensitive topics. Even if they’re concerned with something that could affect the Australian government, they just give a very brief story on it.” Another (TW 2) thought it: “Always portrays how people are fighting in Taiwanese parliament. Not OK, don’t like that way. Don’t really deal with what is happening.” One other (TW 9) was more concerned with the host audience: “It lets me know how Western people look at my country.”

Specialised Television Services

Unfortunately, in the whole sample, there was only one subscriber to the Chinese-language New World pay TV service discussed earlier in this chapter, and disappointingly few viewers of the Chinese programs on community television (Channel 31), a fact attributed by several to poor reception in the suburbs further out. Nevertheless, what those few viewers did say points suggestively—if rather insubstantially—towards an analysis of Channel 31 use based on country of origin or, more specifically, on whether or not there is or has been an established, institutionally based discourse of ethnic identity and of inter-ethnic relations in the countries from which the respondents have come.

Of the fourteen respondents who watched Channel 31 at least sometimes, five were from Indochina, five from Southeast Asia, three from the Mainland and one from Hong Kong. All the Southeast Asian and Indochinese respondents who watched the Asian community TV program counterbalanced their criticism of its poor production standards with the belief that Channel 31 is a valuable social asset that should be maintained. Although widely separated in socioeconomic terms, one thing Southeast Asian and Indochinese respondents do have in common is that they come from a part of the world where ethnic Chinese are in the minority. “Chineseness” was (and is) an issue of potentially great personal seriousness in both Malaysia and Vietnam in a way that it has never been in China. In countries where such minority Chinese communities exist, there are ethnically defined Chinese community organisations which fulfil both practical and spiritual functions at the local level, in a situation where state institutions are indifferent, actively hostile or just not equipped to perform such functions, and which mediate between the Chinese community and the government. It may be that the Southeast Asian and Indochinese respondents’ experience of these organisations as a form of civil society leads them to identify themselves with the Asian program on Channel 31, much as they do with their community ethnic organisations such as the Chinese Association of Victoria and the Indo-Chinese Ethnic Chinese Association of Victoria. VC 7’s view summed up this attitude: “It’s important that there should be such a service.”

We have noted that, in addition to its evening news program in English, SBS broadcasts a number of news services in other languages, including Mandarin and Cantonese, in morning timeslots. This is the WorldWatch programming examined earlier. Figure 2.3 shows the numbers of households who watched the Chinese-language services on WorldWatch. By comparison, there were only five households which regularly watched the SBS news in English, one in each of the groups in the sample, although—as noted—many more across all groups watched news in English on the other channels.

Figure 2.3: Households regularly watching SBS Chinese-language services