How to Shell a Crawfish

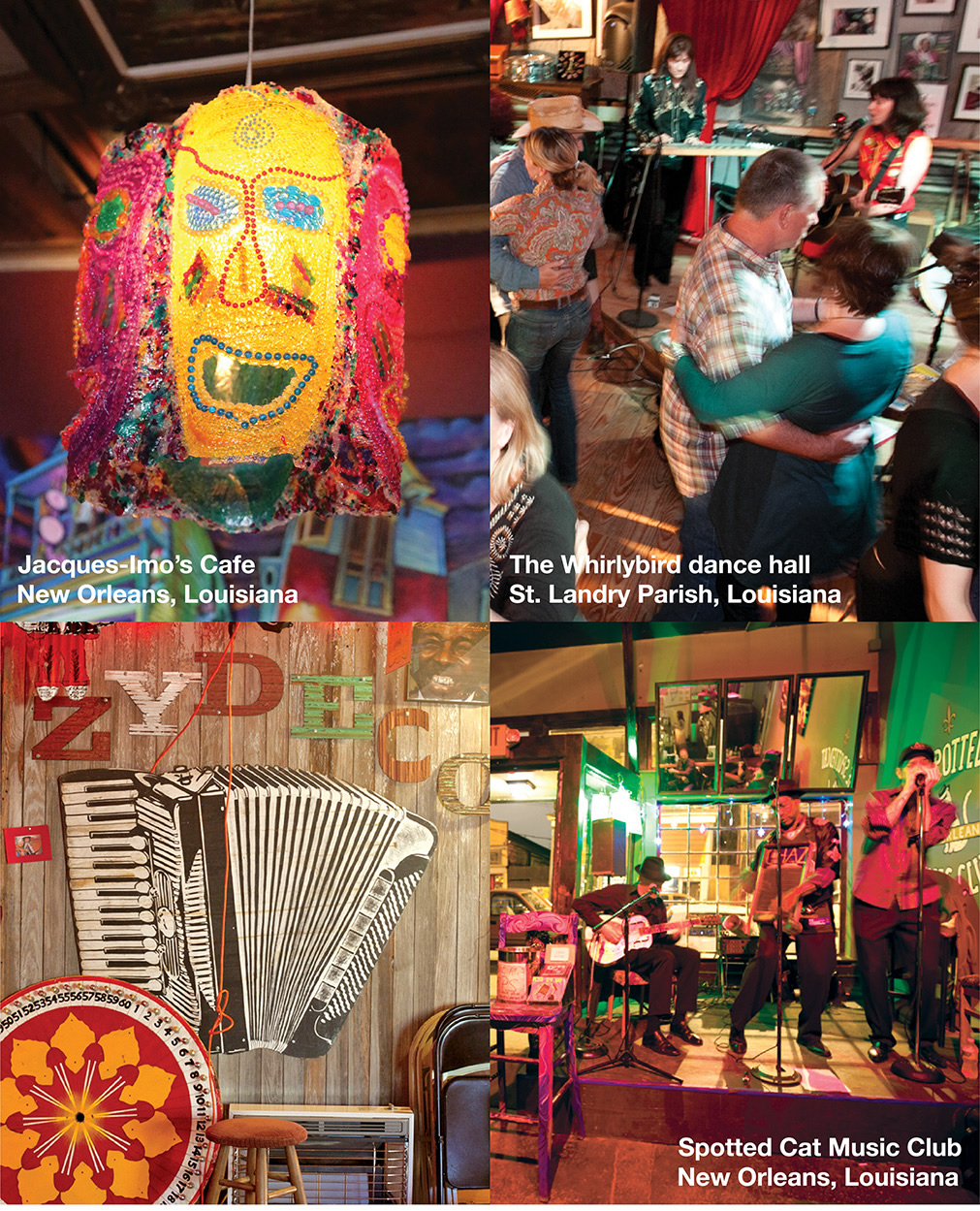

Cajun Country

Small but feisty, southern Louisiana is home to about 700,000 people, about a third of the state, and about 300 miles of coastline. Its heart is 40 miles from the Gulf of Mexico, 70 miles from Texas, and 80 miles from New Orleans. And it’s a world unto itself.

Originally called Acadiana, Cajun country was named for its French-Canadian settlers who fled Canadian colonies after the British wrested those colonies from the French in the late 1750s.

Exiles from the prosperous French New World colony of Acadia (which included Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and Prince Edward Island in Canada, and part of the state of Maine) moved south—all the way south, to Louisiana—to hook up with what was then the largest of the French colonies in the Americas.

They first settled upriver of New Orleans in the area named St. James Parish, and later spread west and founded settlements along Bayou Teche and Bayou Lafourche.

This trio came to be known as Acadiana, and the Acadians who lived there were called “Cajuns.”

Today we know that Cajun is not really about geography: It is a culture with its own distinct food, music, economic conditions (both very high and very low), and even governmental traditions. The Cajun culture makes this especially active, vibrant region of Louisiana distinct from all others. It’s home to zydeco music, curtains of Spanish moss, hurricane cocktails, and just plain hurricanes. It has streetcars and oyster po’boys. Folks here drink coffee with chicory and eat Tabasco sauce on most things.

The area is also renowned for its Mardi Gras celebrations, its amazing Garden District, and the Audubon Zoo. When people doubt what America has contributed to the world, we would do well to show them this particularly zesty slice of our collective pie.

New Orleans, Louisiana, was founded in 1718 by the Montreal-born French colonist Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne. Called the Crescent City because it sits on a crescent-shaped bend in the Mississippi River, it was ruled variously by Spain and France until the Americans got hold of it in the Louisiana Purchase of 1803, still known as “the greatest land bargain in U.S. history” (more than 800,000 square miles from Mississippi to the Rockies sold for between 3 and 4 cents an acre).

New Orleans constantly ranks in polls, novice-run and expert-produced alike, as one of the nation’s top dining destinations. Indeed New Orleanians take food very seriously; it is the local obsession that not even Saints football can compete with—and that’s saying a lot in the Drew Brees era.

From the beginning, New Orleans has been a place with its own mind, a rugged individualist among American cities. It has its own vernacular: The streets are rues; the counties are parishes. It has its own customs: The dead are buried in above-ground mausoleums (the city is below sea level). It has its own religion: The city has always been predominantly Catholic, as opposed to the Anglo-Saxon Protestant norm of the day in which it was founded. And it has also always been heavily populated by African-Americans.

Well before the Civil War, Africans who entered New Orleans in shackles had the chance to live free and work for themselves. As Lolis Eric Elie, a columnist for the New Orleans Times-Picayune, put it: “The French in New Orleans had different conceptions about slavery than the English in the rest of the country.” Slaves could own property, and those who could afford it were allowed to buy their freedom and establish their own part of town.

Tremé (treh-MAY), the first of those areas for freed slaves, today is widely considered the oldest black neighborhood in the United States. Established in the late 1700s and incorporated into New Orleans in 1812, it’s where the country’s first African-American daily newspaper was born. (Since 2010, the neighborhood has been the subject of a fictional TV program that shares its name and explores the city’s long road to recovery and flood-proof culture in the wake of Hurricane Katrina.)

For a time before the Civil War, New Orleans was one of the richest cities in America, and you can see evidence of what that wealth was like in the Garden District, the premier neighborhood lined with Greek Revival and Victorian-style homes that were built in antebellum days.

New Orleans was firmly with the Confederacy for economic reasons: Slave labor enabled the sugar and cotton plantations of the Mississippi Valley. When the war came, New Orleans was one of the jewels in the Confederacy’s crown because it controlled access to the Mississippi River from the Gulf of Mexico.

Despite this, New Orleans wasn’t particularly well protected, and the Union took it over in the late spring of 1862. This was a turning point in the War: When the Mississippi River was claimed by the Union forces, the Confederacy was essentially cut in two, making it significantly weaker.

Historians say that brunch was invented in this town: Madame Bégué, a German immigrant to the city who married a Frenchman, opened a restaurant in 1863 that became famous for its “second breakfast,” a multicourse affair served at 11 a.m. daily. (Other dishes invented in New Orleans include Bananas Foster, which came about at Brennan’s, and Oysters Rockefeller, which first showed up at Antoine’s.)

Parties in New Orleans are legendary. The king is Mardi Gras. Based on thousand-year-old pagan fertility rites including the Roman Saturnalia, Mardi Gras has become one of the great American festivities. (When Christianity came to Rome, the Catholics adopted these festivals. That’s why Mardi Gras is associated with Catholicism, why it’s held as a precursor to Lent, and how it got its name. In French, Mardi Gras means “Fat Tuesday”—a day of feasting before the start of Lenten fasts.)

Mardi Gras has been going on in New Orleans since the city’s first days; the earliest one was held in 1703. Since then it has been dominated by “krewes,” local nonprofit crews or clubs financed by dues and fund-raising projects.

It actually starts two weeks before the big Mardi Gras day with parades galore (most follow the same route: St. Charles Avenue through the Uptown, Garden District and Lower Garden District neighborhoods, before proceeding through the Central Business District and disbanding at the border of the French Quarter.)

Notable paraders include the so-called Mardi Gras Indians—African-Americans who feel tied to Native Americans by bloodlines and a history of resistance—who have paraded informally, in terrifically decorated, feathered, beaded, and brightly winged costumes, at Mardi Gras for more than a century.

Everything is purple (for justice), gold (for power), and green (for faith)—buntings, flags, tinsel displays, masks, wreaths, beads thrown from floats, and the icing on the famous Mardi Gras king cake. Find the little gold or plastic baby Jesus inside for good luck or, some say, the obligation to bring the king cake next year.

The other important New Orleans party is Jazz Fest, officially known as the New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival, first held in 1970. When it was founded, Jazz Fest was a very deliberate thing, an attempt by city leaders to recognize New Orleans as the birthplace of jazz.

To that end, they hired George Wein, jazz impresario and the founder of the Newport Jazz Festival, to come down and orchestrate something suitable.

Wein delivered, producing an all-day concert with various acts playing on different stages in a “something for everyone” approach that quickly became an annual tradition.

Today there are some 12 stages, the event lasts four days, and headliners include the likes of Fleetwood Mac. (Previous Jazz Fest performers have included Aretha Franklin, Bob Dylan, Santana, Paul Simon, B.B. King, Lenny Kravitz, Linda Ronstadt, Willie Nelson, and many more legends.)

There’s no way to talk about New Orleans without mentioning August 29, 2005, the day Hurricane Katrina—one of the strongest storms to impact the United States in a century—struck the city and breached its levees. “New Orleans will forever exist as two cities,” declared a Times-Picayune headline. “The one that existed before that date, and the one after.”

New Orleans’s many fans around the globe watched in horror as the beloved city sank beneath the water, its Superdome filling with more than 10,000 evacuees, boats washing onto highways, residents stranded and trapped in their homes, hundreds dead, and thousands displaced.

Our collective party capital, the Crescent City, was dealt a bracing blow. But New Orleans is a town with a special spirit, and it has risen again—if not exactly to its former carefree glory, then at least to a place where the good times are even more cherished.

When people doubt what America has contributed to the world, we would do well to show them Cajun Country, a particularly zesty slice of our collective pie.

Historians say that brunch was invented in New Orleans. So was Bananas Foster, which came about at Brennan’s, and Oysters Rockefeller, which first showed up at Antoine’s.

New Orleans is a town with a special spirit, and it has risen again—if not exactly to its former carefree glory, then at least to a place where the good times are even more cherished.

In Cajun country proper, the big city is Lafayette, Louisiana, about two hours west of New Orleans. How do you know you’re in Lafayette? The street signs say Rue instead of Street. You spot herons and ibises, alligators and yellow-bellied turtles along the bayou. Lacy curtains of Spanish moss hang down from the trees, and rows of okra grow in fields nearby.

A bona fide oil boom has made once-poor Lafayette fairly prosperous, though, so now instead of seeing swamp houses you’re more likely to find tidy suburbs. (It helps that Hurricane Katrina didn’t much touch the town, too.)

In nearby Breaux Bridge, about 10 minutes away from Lafayette, you can experience what is quite possibly the best amalgam of music and food anyplace, anywhere: the “zydeco breakfast” held at Café Des Amis every Saturday from 8:30 to 11:30 a.m. It’s a bit early for some, but it’s always packed. They garnish your Bloody Mary with pickled green beans and serve platters of cheese grits with andouille sausage and floorboard-shaking, accordion-driven dance music.

Cajun food is defined by its unique mixture of French home-cooking techniques and bayou ingredients. The latter refers to everything from the okra that the African slaves brought over and the cayenne pepper imported from the Caribbean to the native Louisiana blue crabs, crawfish (“suck the head, and eat the tail”), oysters, and shrimp. It’s a heady combination that has naturally led to the headiest and most aromatic and richly spiced dish in the American food canon: gumbo.

Another regional favorite is jambalaya. “Jambalaya and a crawfish pie and filé gumbo / ’Cause tonight I’m gonna see my ma cher amio. / Pick guitar, fill fruit jar and be gay-o / Son of a gun, we’ll have big fun on the bayou.” So sang the late, great Hank Williams Sr. in 1952.

In many ways, jambalaya is the ultimate fusion dish: It was first made by Spanish settlers in New Orleans who were seeking to re-create their own paella—but the Cajuns quickly adopted it and made it their own.

Jambalaya is one of those robust, throw-everything-in-the-pot meals, a crowd-pleaser with especially bright, zesty flavors, that’s just designed to feed a group. Traditionally, it features shellfish, chicken giblets, spicy andouille sausage, and tasso ham (the peppery smoked pork made not from the hind leg but from the fattier shoulder).

It’s made by browning the meat in a cast-iron pot; adding onions, celery, and green peppers, and sautéing until they are soft; adding rich stock and seasonings and uncooked rice; and simmering over very low heat until the rice is fully cooked.

Variations of the dish and theories on the origin of the name abound. Some say it’s a cross between jamon and paella. Some suspect it comes from the African term ya for rice. Others hold that it came from the Provençal word jambalaia, meaning mishmash. In Cajun country everybody claims this dish.

Now is a good time to talk about Creole cooking, which is essentially the other thing that goes on in New Orleans and its surroundings. The distinction between Creole and Cajun is difficult to define. Folklore suggests that only Louisianans can tell the difference. But of course that doesn’t stop people from trying.

“Creole cooking is more refined than Cajun,” concluded New York Times food editor Craig Claiborne in a 1987 column on gumbo. “While its origins are also classic French, it was influenced by Spanish, African, Italian, and Native American cuisines—that is, by the culinary practices of the ethnic groups that settled in Louisiana.” And indeed there is a New Orleans proverb that goes something like this: “A Creole can feed one family with three chickens, and a Cajun can feed three families with one chicken.”

In general, Creoles lived in the city and had access to better markets and ingredients, while Cajuns lived in the country and had to make do with what was available beyond the city limits. The famous New Orleans chef Paul Prudhomme has said that the difference comes down to African-American people who, as cooks in many Louisiana homes, incorporated the various styles of cooking into their own. In Creole homes, there were servants; in Cajun homes, there were not.

Cajun and Creole cuisines have grown up together and informed each other so much that it’s easier to talk about what they have in common than how they differ. The main conjoiner, as it were, is roux. The base for almost all of the classic French sauces, roux is the starter for the classic gumbos and stews of both Cajun and Creole kitchens.

A classic French chef would say that a roux is a blend of butter (or some other fat, such as lard) and flour. Cajun and Creole chefs take the formula and make it their own, creating a veritable rainbow of roux colors, cooking it until it is dark blond to flavor chicken and other light-meat dishes, sautéing it until it is medium-brown to flavor game dishes, and roasting it until it is almost mahogany for gumbo. Louisiana’s chefs say this proprietary, much-sweated-over roux gives a good gumbo its characteristic richness and nutty flavor.

While some argue that Creole roux is made from butter and the Cajun variety is made from lard, others swear by the opposite. Both sides tend to agree that when you want to make a roux, you can’t even think about leaving the stove to stop stirring until the entire gumbo or stew has come together. Then you get to leave it alone for hours so the flavors will meld and marry.

In Cajun country, the supper club tradition is alive and well—only these aren’t dress-up, stuffy, cocktail party-type affairs. You can don your cowboy boots and eat your crawfish and do the two-step.

In fact, music is integral to enjoying the food in Cajun country. Along with their roux, the Cajuns fleeing Canada for Louisiana brought their French folk music traditions.

These, like the food, became mingled with the local ingredients and customs and took on many variations.

The fiddle drives traditional Cajun music, which in general has lyrics and a woeful tone. Though born of the same roots, zydeco is something different altogether. It’s basically what happens when the blues meet French traditions, and it’s a party: Hard-driving accordions chime in with the fiddles, basses, guitars, and percussion instruments.

The best thing that can happen to you when eating in these parts is to find yourself in a place with great examples of both the food and the sound.

Cajun country is the kind of place where a certain authenticity of spirit is prized.

As the infamously freewheeling political consultant James “The Ragin’ Cajun” Carville once advised, “stand for yourself, be for something, and the hell with it.”

Down here, folks are going to have a good time, dance well, and eat the best that they can for as long as they can. Let the good times roll, indeed.

Folklore suggests that only Louisianans can tell the difference between Creole and Cajun. But of course that doesn’t stop people from trying.

Also sometimes called Haitian Creole, Louisiana Creole is heavily influenced by aspects of west and central African linguistics. It’s the language of some natives of Cajun country.

Cajun Creole, on the other hand, derives more from the language spoken in the French colony of Acadia at the time the Acadians were expelled. But even it is not pure, deriving some of its vocabulary from the Spanish, German, Portuguese, and Haitian Creole that it met when it got to Louisiana.

None of these holds allegiance to any one tradition in Louisiana, and all are wildly entertaining to hear, though they can be a barrier to the uninitiated. You already know ki ça di (kee-sah-DEE) means “what’s up.” Here are a few more to help you get your bearings:

Cher is an abbreviation of the French cherie, meaning “sweetheart” or “dear.” Pronounced “sha,” you’ll hear it in calls from friendly business owners when you walk in—as in, “How ya doin’, cher?” Dat means “that,” and dey means “they.” To crawfish means to “back out of a deal.”

It only adds to the region’s charm when you decipher what someone means when he says: “Fisça da Geda ywum ywum doun bayeou!” (Loose translation: “We relish hunting alligators in the bayou—and eating them, too.”)

~ A Recipe from a Local ~

Hurricane Punch

Sweep away your cares with this fruity but potent cocktail.

Makes 8 1/4 cups Hands-On Time 5 min. Total Time 5 min.

1/2 (64-oz.) bottle red fruit punch

1/2 (12-oz.) can frozen limeade concentrate, thawed

1 (6-oz.) can frozen orange juice concentrate, thawed

1 2/3 cups light rum

1 2/3 cups dark rum

1. Stir together all ingredients. Serve over ice.

Kathy Bowes

Metairie, Louisiana

Crab Cake Hush Puppies

Hush puppies were perhaps the original dog treat. Legend has it that Southern fishermen and Civil War soldiers made the golden nuggets from scraps and tossed them to barking and begging dogs with the simple command: “Hush, puppy.” This version is bound to hush your mouth, too.

Makes 8 servings (about 32 hush puppies) Hands-On Time 30 min. Total Time 40 min.

1 cup self-rising white cornmeal mix

1/2 cup self-rising flour

3 green onions, thinly sliced

1/2 cup finely chopped red bell pepper

1 Tbsp. sugar

1/4 tsp. table salt

8 oz. fresh lump crabmeat, drained

1 large egg

3/4 cup beer

Vegetable oil

1. Stir together cornmeal mix, flour, green onions, bell pepper, sugar, and salt in a large bowl.

2. Pick crabmeat, removing any bits of shell. Stir in crabmeat, egg, and beer until just moistened. Let stand 10 minutes.

3. Pour oil to depth of 2 inches into a Dutch oven; heat to 360°.

4. Drop batter by tablespoonfuls into hot oil, and fry, in batches, 2 to 3 minutes or until golden brown, turning once. Serve with your favorite rémoulade or cocktail sauce.

Rémoulade

You can make this sauce ahead to serve with boiled shrimp, spread on sandwiches, or use as a dip for hush puppies. Leftover sauce will keep in the refrigerator up to two weeks.

Makes 5 cups Hands-On Time 10 min. Total Time 10 min.

6 garlic cloves, peeled

3 celery ribs, chopped

1/3 cup white vinegar

1/2 cup egg substitute

1/4 cup ketchup

1/4 cup prepared horseradish

1/4 cup Creole mustard

1/4 cup yellow mustard

2 Tbsp. mild paprika

2 Tbsp. Worcestershire sauce

1 Tbsp. hot sauce or to taste

1 tsp. ground red pepper

1 1/2 cups vegetable oil

6 green onions, sliced

1. Process first 12 ingredients in a blender or food processor until smooth. With blender running, pour oil in a slow, steady stream until thickened. Stir in green onions; add kosher salt and black pepper to taste. Cover and chill until ready to serve.

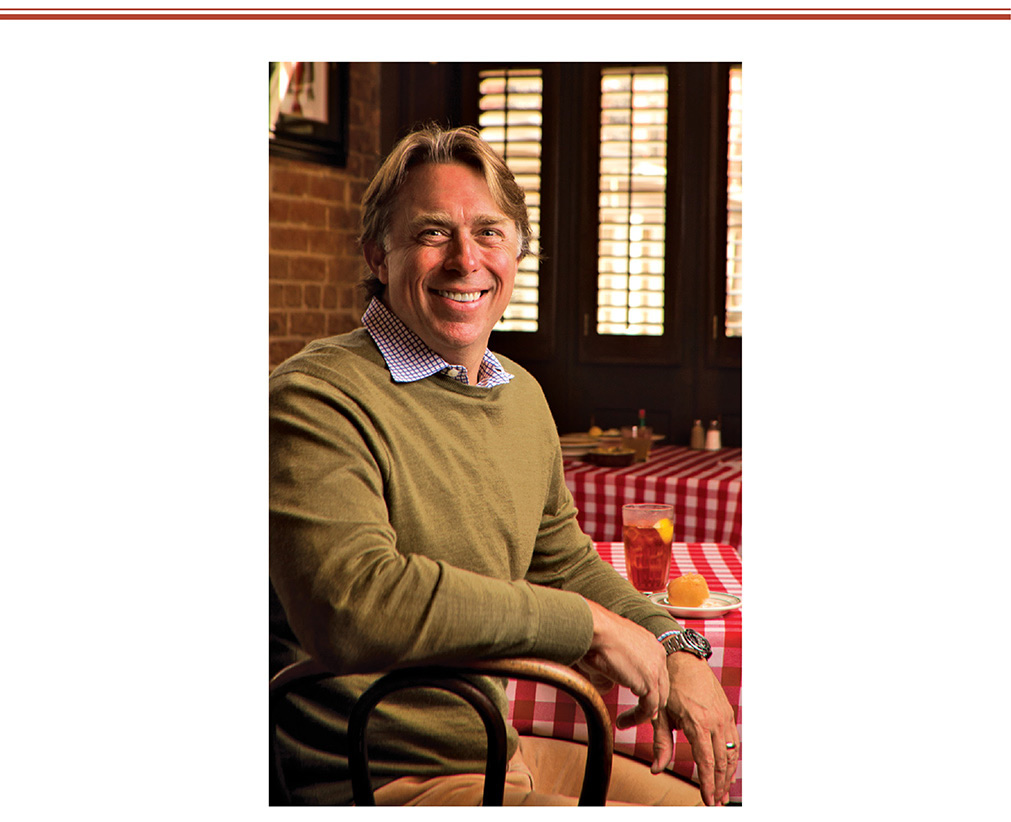

Meet Chef

John Besh

Born in Meridian, Mississippi, and raised in southern Louisiana, Besh was cooking at the highest level at his New Orleans restaurant August long before the hurricane. But it was afterward that he came to symbolize the city’s dedication to getting back on its feet, starting first at the table. A former Marine who led an infantry squad in the Persian Gulf War, Besh toured his flooded city in a little speedboat delivering food.

His efforts earned him just about every award there is for feeding people, including a “best new chef” moniker from Food & Wine and a best restaurant award for August from the James Beard Foundation.

He’s now busy raising four boys and running nine restaurants (eight in New Orleans and one in San Antonio, Texas.) His eateries range from upscale French-Cajun canteen August to Soda Shop, a cafe inside the National World War II Museum.

“This recipe requires high-quality wild shrimp. Of course, I prefer wild Gulf shrimp from the waters I know. You can mix up your vegetables with the shrimp, using whatever’s fresh and local.” —John Besh

Pickled Shrimp

Makes 10 servings Hands-On Time 40 min. Total Time 1 hour, 15 min., plus 1 day for pickling

BRINE

2 cups rice vinegar

Zest and juice of 1 lemon

Zest and juice of 1 orange

1/2 cup sugar

1 Tbsp. coriander seeds

1 Tbsp. mustard seeds

1 Tbsp. black peppercorns

1 Tbsp. dried crushed red pepper

5 garlic cloves, thinly sliced

2 bay leaves

Pinch of kosher salt

REMAINING INGREDIENTS

2 lb. unpeeled large wild Gulf shrimp

12 small carrots with tops

12 fresh green beans

12 pearl onions, peeled

12 small fresh okra

1. Prepare the Brine: Combine all brine ingredients in a large nonreactive saucepan. Add 2 1/2 cups water, and bring to a boil. Remove pan from heat, and cool 10 minutes.

2. Prepare the Remaining Ingredients: Bring a large pot of salted water to boil; add shrimp, and remove pan from heat. Let stand 1 minute or until shrimp turn pink. Drain and rinse with cold water. Peel and devein. Peel carrots, trim greenery to 1 inch, and halve lengthwise. Pack shrimp, carrots, green beans, pearl onions, and okra in alternating layers into a 1-gal. glass jar or very large glass bowl. Pour hot brine to cover over the shrimp and vegetables. Cover and cool. Refrigerate overnight. Serve right from the jar when you’re ready.

~ You've Gotta Try ~

Gumbo

It almost always involves crabmeat and shrimp, sometimes oysters, sometimes chicken, sometimes okra (the name is said to come from the African word for okra), and always a dark brown sauce with a roux (a combination of fat and flour that thickens and enriches many dishes in and beyond Cajun country).

Gumbo may be seasoned and further thickened with filé (the powdered, dried leaves of the sassafras tree), spiked with spicy tasso or Spanish chorizo or both, scented with bay leaf, and bruised with plenty of black pepper.

~ A Recipe from a Local ~

Chicken-Tasso-Andouille Sausage Gumbo

Tasso is a spicy, cayenne-rubbed, smoked pork popular in many Cajun dishes.

Makes 5 qt. (about 20 servings) Hands-On Time 45 min. Total Time 5 hours

4 lb. skinned and boned chicken thighs

1 lb. andouille or smoked sausage

1 lb. tasso or smoked ham

1 cup vegetable oil

1 cup all-purpose flour

4 medium onions, chopped

2 large green bell peppers, chopped

2 large celery ribs, chopped

4 large garlic cloves, minced

4 (32-oz.) boxes chicken broth

1 1/2 tsp. dried thyme

1 tsp. black pepper

1/2 tsp. ground red pepper

1/3 cup chopped fresh parsley

Hot cooked rice

Garnishes: sliced green onions or chopped fresh parsley, filé powder

1. Cut first 3 ingredients into bite-size pieces. Place in a large Dutch oven over medium heat, and cook, stirring often, 20 minutes or until browned. Drain on paper towels. Wipe out Dutch oven with paper towels.

2. Heat oil in Dutch oven over medium heat; gradually whisk in flour, and cook, whisking constantly, 25 minutes or until mixture is a dark mahogany.

3. Stir in onion and next 3 ingredients; cook, stirring often, 18 to 20 minutes or until tender. Gradually add broth. Stir in chicken, sausage, tasso, thyme, black pepper, and ground red pepper.

4. Bring mixture to a boil over medium-high heat. Reduce heat to medium-low, and simmer, stirring occasionally, 2 1/2 to 3 hours. Stir in parsley. Remove from heat; serve over hot cooked rice.

For Shrimp-Tasso-Andouille Sausage Gumbo: Omit chicken thighs and, in Step 4, stir in 4 lb. medium-size raw shrimp, peeled and deveined, during the last 15 minutes of cooking.

Philip Elliott

Baton Rouge, Louisiana

Meet Chef

Emeril Lagasse

The South was, perhaps, an unlikely destination for Lagasse, a native of Fall River, Massachusetts, who found his passion for cooking in high school while working in a Portuguese bakery. After culinary school in Rhode Island, and stints in France and the Northeast, Lagasse was hired in 1982 by the famed Brennan family of New Orleans restaurateurs, to take over their flagship Crescent City restaurant, Commander’s Palace, from Paul Prudhomme.

He left Commander’s Palace in 1990 to open Emeril’s. It was an instant hit, a fusion of all of the flavors Emeril himself loved best, including Cajun, Portuguese, and Italian. It was named Restaurant of the Year by Esquire that year.

Today, Lagasse has an empire of restaurants (13 at last count), a line of cookware, and a thick stack of best-selling cookbooks. In addition, he runs a foundation that supports children’s enrichment programs in and around New Orleans.

These oyster po’boys are from his 2012 cookbook, Emeril’s Kicked-Up Sandwiches.

“Oh, baby. The crispy fried ‘ersters,’ the salty bacon, and the creamy avocado all come together in this ultimate oyster sandwich. If you’ve ever wanted to re-create the experience of a fried oyster po’boy from New Orleans, save the flight—this is it!” —Emeril Lagasse

Fried Oyster Po’Boys with Jalapeño Mayonnaise and Avocado

Traditional New Orleans po’boy loaves are airy, long French breads. If you cannot find po’boy bread in your area, substitute any long Italian or French bread loaves that are not too dense. If the only bread you can find is very dense, consider pinching out the center doughy portions so that your po’boy is not overly bready.

Makes 4 servings Hands-On Time 40 min. Total Time 1 hour, 10 min.

1 1/4 cups buttermilk

1/2 cup your favorite Louisiana red hot sauce

1/4 cup Emeril’s Original Essence or Creole seasoning, divided

4 dozen oysters, shucked and drained [or 2 (16-oz.) containers]

1 1/2 cups masa harina (corn flour)

1 1/2 cups all-purpose flour

Vegetable oil

4 (8-inch) lengths po’boy bread or French or Italian loaves, split lengthwise

3 Tbsp. butter, melted

1 cup shredded lettuce

1 medium tomato, thinly sliced

1 avocado, thinly sliced

8 to 12 cooked bacon slices

1. Combine the buttermilk, hot sauce, and 2 Tbsp. of the Essence in a medium mixing bowl, and stir to combine. Add the oysters, and marinate in the refrigerator up to 30 minutes.

2. In a separate medium bowl, combine the masa harina, all-purpose flour, and remaining 2 Tbsp. Essence; stir to blend.

3. Pour oil to depth of 2 1/2 inches into a medium-size heavy pot or deep-fryer; heat to 360°. Working in batches, remove the oysters from the buttermilk marinade, and transfer them to the masa harina mixture. Dredge to coat, shaking to remove any excess breading. Cook the oysters in small batches in the hot oil 2 to 3 minutes or until golden brown and crispy. Remove with a slotted spoon, and transfer to paper towels to drain. Sprinkle with salt and black pepper to taste.

4. To assemble: Spread the bottom halves of the bread with the melted butter. Generously spread the top halves of the bread with Jalapeño Mayo. Divide the oysters evenly among the bottom halves, followed by the lettuce, tomato, avocado, and bacon. Place the top halves of the bread over the fillings and press lightly. Cut each sandwich in half, and serve immediately.

Jalapeño Mayo

Keep this in the fridge to wake up your old standby roast beef or turkey-and-cheese sandwich, or use it with fried seafood, such as the oyster po’boy.

Makes 1 3/4 cups Hands-On Time 15 min. Total Time 15 min.

1 large egg, at room temperature

1 large egg yolk, at room temperature

2 Tbsp. chopped fresh cilantro leaves (optional)

1 Tbsp. freshly squeezed lemon juice

1 tsp. minced garlic

1/2 tsp. Dijon mustard

2 to 3 jalapeños, stemmed, seeded, and chopped

1 cup vegetable oil

3/4 tsp. table salt

1/4 tsp. freshly ground black pepper

1. In a food processor or a blender, combine the egg, egg yolk, cilantro (if using), lemon juice, garlic, mustard, and jalapeños; process until smooth. With the motor still running, add the oil in a thin stream until a thick emulsion is formed. Add the salt and pepper, and transfer the mayonnaise to a nonreactive container. Cover and refrigerate until ready to use or up to 3 days.

Note: This recipe is prepared with raw eggs. Consuming raw eggs may increase your risk of foodborne illness. For a cooked alternative, omit the egg, egg yolk, and salt, and blend the remaining ingredients into 1 1/2 cups prepared mayonnaise (such as Hellmann’s).

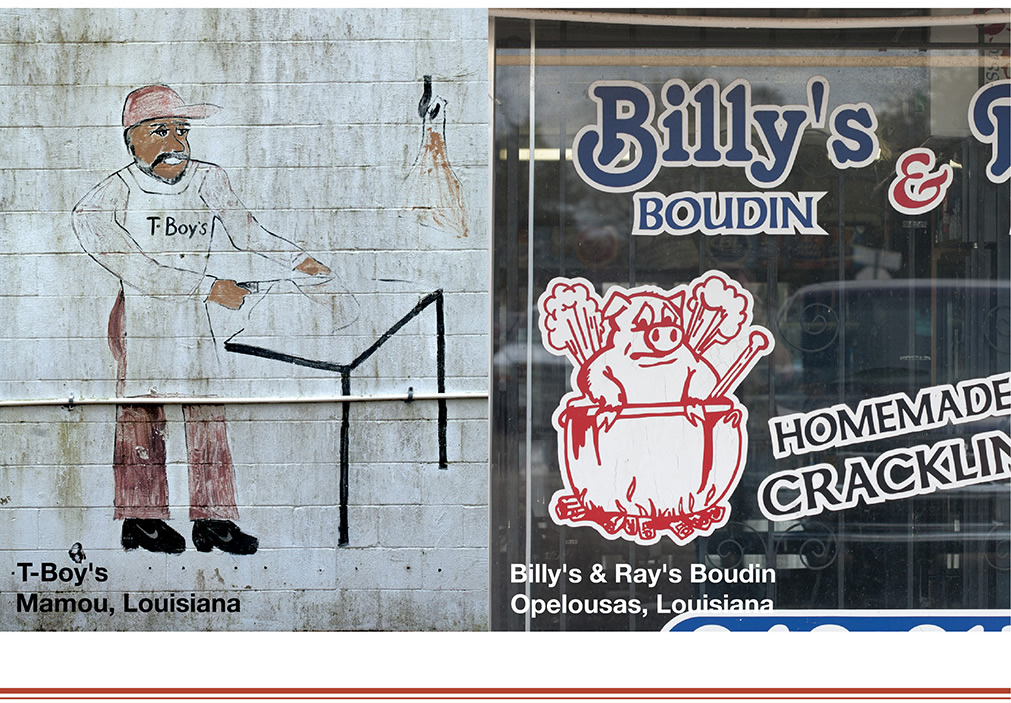

If you think you already know what boudin (BOO-dan) is, you’re probably thinking of its French ancestors, boudin blanc (a white-meat-only sausage made of pork and chicken) and boudin noir (a darker, richer version of the same, made with pig blood). In Cajun country, boudin is something else altogether, a sausage made from the shoulder, neck, and sometimes trotters (that means feet) and liver of the hog, combined with rice, onion, lots of freshly ground black pepper, and a bit of cayenne.

The meat is coarsely ground, mixed with the other ingredients, usually by hand, and either rolled into sausage balls and fried (“boudin balls”) or pumped into casings, and then either gently simmered or smoked until done. Here’s where it gets interesting: To eat boudin like a Cajun, you bite a hunk off the link, and then, using your fingers or, preferably, just your teeth, you pull the meat out of the casing. This is often but not always accompanied with bracing Creole mustard (like Dijon, but spicier), a cold beer, and maybe some crackers. It is messy, it is visceral, and it is not for the faint of heart; that said, it is singularly delicious.

Although Cajun country is not exactly enormous, it offers a TON of boudin joints to choose from. Lots of folks like the Eunice Superette & Slaughter House. Others swear by Johnson’s Boucaniere in Lafayette. The Lafayette Parish Convention and Visitors Commission’s website (www.cajunboudintrail.com) lists the best places to get your boudin on.

~ A Recipe from a Local ~

John’s Red Beans & Rice

This one-dish meal is a favorite comfort food served throughout Louisiana. Long simmering helps the flavor develop.

Makes 10 to 12 servings Hands-On Time 30 min. Total Time 3 hours, 55 min.

1 (16-oz.) package dried red kidney beans

1 lb. mild smoked sausage, cut into 1/4-inch-thick slices

1 (1/2-lb.) smoked ham hock, cut in half

1/4 cup vegetable oil

3 celery ribs, diced

1 medium-size yellow onion, diced

1 green bell pepper, diced

3 bay leaves

3 garlic cloves, chopped

2 Tbsp. salt-free Cajun seasoning

1 tsp. kosher salt

1 tsp. dried thyme

1 tsp. ground black pepper

3 (32-oz.) boxes reduced-sodium chicken broth

Hot cooked rice

1. Place beans in a large Dutch oven; add water 2 inches above beans. Boil 1 minute; cover, remove from heat, and let stand 1 hour. Drain.

2. Cook sausage and ham in hot oil in Dutch oven over medium-high heat 8 to 10 minutes or until browned. Drain sausage and ham on paper towels, reserving 2 Tbsp. drippings. Add celery and next 8 ingredients to drippings; cook over low heat, stirring occasionally, 15 minutes.

3. Add broth, beans, sausage, and ham to Dutch oven. Bring to a simmer. Cook, stirring occasionally, 2 hours or until beans are tender. Discard ham hock and bay leaves. Serve over hot cooked rice.

Chef-Owner John Harris, Lilette Restaurant

New Orleans, Louisiana

New Orleans Barbecue Shrimp

When you see the words barbecue and shrimp together in New Orleans, don’t be looking for the grill. Barbecue shrimp here is actually a lot more like a Belgian mussels dish, with the main ingredient cooked up a skillet at a time in a flavorful sauce, served in bowls, and eaten with your hands and plenty of good bread to sop up the sauce. This version involves marinating the shrimp ahead of time for maximum flavor and finishing them in the oven for incredible ease.

Makes 6 to 8 servings Hands-On Time 10 min. Total Time 2 hours, 30 min.

4 lb. unpeeled, large fresh shrimp or 6 lb. large shrimp with heads on

1/2 cup butter

1/2 cup olive oil

1/4 cup chili sauce

1/4 cup Worcestershire sauce

2 lemons, sliced

4 garlic cloves, chopped

2 Tbsp. Creole seasoning

2 Tbsp. lemon juice

1 Tbsp. chopped parsley

1 tsp. paprika

1 tsp. oregano

1 tsp. ground red pepper

1/4 tsp. hot sauce

French bread

1. Spread shrimp in a shallow, aluminum foil-lined broiler pan.

2. Combine butter and next 12 ingredients in a saucepan over low heat, stirring until butter melts, and pour over shrimp. Cover and chill 2 hours, turning shrimp every 30 minutes.

3. Preheat oven to 400°. Bake, uncovered, for 20 minutes; turn once. Serve with bread.

Chicken, Shrimp, and Ham Jambalaya

Rice is the main thing in jambalaya. After that, anything goes. This recipe, adapted from Eula Mae’s Cajun Kitchen by legendary Cajun cooks Eula Mae Doré and Marcelle R. Bienvenu, involves shrimp, chicken, and ham. But you can incorporate smoked sausage, pork, oysters, or whatever you have on hand. For more kick, add an extra dash of hot sauce to each serving.

Makes 6 to 8 servings Hands-On Time 45 min. Total Time 1 hour, 50 min.

2 lb. unpeeled, medium-size raw shrimp

1 1/2 lb. skinned and boned chicken thighs, cut into 1-inch cubes

1 tsp. table salt

1/8 tsp. freshly ground black pepper

1/8 tsp. ground red pepper

2 Tbsp. vegetable oil

1/2 lb. cooked ham, cut into 1/2-inch cubes

4 garlic cloves, chopped

2 medium-size yellow onions, chopped (2 cups)

2 celery ribs, chopped (1 cup)

1 medium-size green bell pepper, chopped (1 cup)

3 cups chicken broth

1 (14.5-oz.) can diced tomatoes

3 green onions, chopped (1/2 cup)

2 Tbsp. chopped fresh parsley

2 cups uncooked long-grain rice

1 tsp. hot sauce

1. Peel shrimp; devein, if desired.

2. Sprinkle chicken evenly with salt, black pepper, and red pepper.

3. Heat oil in a Dutch oven over medium heat. Add chicken, and cook, stirring constantly, 8 to 10 minutes or until browned on all sides. Remove chicken using a slotted spoon.

4. Add ham to Dutch oven, and cook, stirring constantly, 5 minutes or until lightly browned. Remove ham using a slotted spoon.

5. Add garlic and next 3 ingredients to Dutch oven; stir to loosen particles from bottom. Stir in ham and chicken. Cover, reduce heat to low, and cook, stirring occasionally, 20 minutes.

6. Add chicken broth. Bring to a boil over medium-high heat; cover, reduce heat to low, and simmer 35 minutes. Add tomatoes and next 3 ingredients. Bring to a boil over medium-high heat; cover, reduce heat to medium-low, and simmer 20 minutes. Stir in shrimp and hot sauce; cook, covered, 10 more minutes or until liquid is absorbed and rice is tender.

Cajun-Baked Catfish

Fried catfish is a favorite in and beyond Louisiana. This oven-fried version renders flavorful and crispy fish with no deep-frying and less mess.

Makes 4 servings Hands-On Time 15 min. Total Time 45 min.

2 cups cornmeal

2 tsp. table salt

1 Tbsp. black pepper

8 (3- to 4-oz.) catfish fillets

2 Tbsp. Cajun seasoning

1 to 2 tsp. seasoned salt

1/4 cup butter, melted

Garnish: lemon wedges

1. Preheat oven to 400°. Combine first 3 ingredients. Dredge catfish fillets in cornmeal mixture; place fillets, skin sides down, on a greased baking sheet.

2. Combine Cajun seasoning and seasoned salt; sprinkle over fillets. Drizzle with butter.

3. Bake at 400° for 30 minutes or until golden and fish flakes with a fork.

~ A Recipe from a Local ~

Creole Potato Salad

Makes 10 to 12 servings Hands-On Time 35 min. Total Time 1 hour, 10 min.

5 lb. baby red potatoes

1/4 cup dry shrimp-and-crab boil seasoning

12 hard-cooked eggs, peeled and chopped

1 1/2 cups finely chopped celery

1 cup finely chopped green onions

1 1/2 Tbsp. Creole seasoning

2 cups mayonnaise

1/3 cup Creole mustard

1. Bring potatoes, shrimp-and-crab boil seasoning, and 4 qt. water to a boil in a large stockpot over high heat. Boil 20 minutes or until tender; drain and cool 20 minutes.

2. Peel potatoes; cut into 3⁄4-inch pieces. Toss together potatoes, eggs, and next 3 ingredients; stir in mayonnaise and mustard.

For Cajun Shrimp Potato Salad: Stir in 1 lb. peeled, medium-size cooked shrimp.

Sharon Cheadle

Slidell, Louisiana

~ You've Gotta Try ~

Crawfish

The diminutive creatures, which thrive at the bottom of muddy waters, are closely related to, and often referred to as a small freshwater version of, the much-lauded lobster. Their meat is delicate and sweet, the flesh meltingly tender, the flavor concentrated. Crawfish meat is “the candy of the salty world,” the great Cajun chef Paul Prudhomme has said. “It has a very sweet, creamy, twice-as-rich-as-lobster taste.”

The preparation and adoration of crawfish most likely began in France (where a European variety is raised), traveled to Nova Scotia, and then migrated to New Orleans right along with the French Canadians. Prime breeding ground for crawfish is in the nearly 1 million acres of wooded swampland known as the Atchafalaya Basin in south-central Louisiana. In the surrounding areas, locals discovered that they could raise crawfish in ponds, and that crawfish were an ideal crop to rotate with rice.

Although you can easily buy cooked crawfish tails frozen year-round, as many Cajun restaurants do, fresh crawfish do indeed have a season, from late January to early June. Their abundance in the area gave rise to the traditional spring crawfish boils in which great cauldrons of shellfish are boiled in spiced water and dumped onto newspaper-lined tables, along with sausages and sometimes new potatoes and sweet corn, for family and neighbors to feast upon. At boils, crawfish are eaten in the most traditional way: “Suck the head, and eat the tail,” as the saying goes. The head is where delectable fatty meat is stored, and the tail is a nice little chunk of tender seafood.

Crawfish are sacred to the cooks of Cajun country in other ways, too. Probably the single most popular presentation is in a rich one-pot stew called étouffée. It literally means “smothered” and, like so many Cajun dishes, begins with a roux. Historians say it was created in the 1920s in the kitchens of the old Hebert Hotel in the town of Breaux Bridge, about 9 miles northeast of Lafayette in St. Martin Parish.

Today Breaux Bridge bills itself as the “crawfish capital of the world.” The town hosts an annual crawfish festival the first weekend in May which, naturally, involves a crawfish étouffée cook-off.

How to Shell a Crawfish

1. Twist and snap head away from tail. Set aside.*

2. Peel shell away from widest part of tail.

3. Hold tip of tail; gently pull out tender meat.

*Note: Suck flavorful juices from the head, if desired.

Crawfish Boil

Nothing is better on a spring or early summer night than a traditional Louisiana crawfish boil. Repeat as needed to feed a crowd. Serve with lemon wedges, hot sauce, rémoulade, French bread, and good Louisiana beer.

Makes 4 servings Hands-On Time 1 hour Total Time 2 hours, 25 min.

10 bay leaves

1 cup table salt

3/4 cup ground red pepper

1/4 cup whole allspice

2 Tbsp. mustard seeds

1 Tbsp. coriander seeds

1 Tbsp. dill seeds

1 Tbsp. dried crushed red pepper

1 Tbsp. black peppercorns

1 tsp. whole cloves

4 celery ribs, quartered

3 medium onions, halved

3 garlic bulbs, halved crosswise

2 lb. new potatoes

1 lb. andouille sausage

5 lb. crawfish

1. Bring 1 1/2 gallons water to a boil in a 19-qt. stockpot over high heat. Add bay leaves and next 12 ingredients to water. Return to a rolling boil. Reduce heat to medium, and cook, uncovered, 15 minutes.

2. Add potatoes and sausage. Return to a rolling boil over high heat. Cook 10 min.

3. Add crawfish. Return to a rolling boil; cook 5 minutes. Remove stockpot from heat; let stand 30 minutes. (For spicier crawfish, let stand 45 minutes.) Drain. Serve crawfish, potatoes, and sausage on large platters or newspaper.

Meet Cajun Maven

Kay Robertson

They make cedar duck calls and run a successful sport-hunting business. Miss Kay is the matriarch who brings the family together with her Cajun cooking.

Kay is fully aware of her power, wielding her kitchen skills to settle disputes and foster happy relations amongst her brood. Consequently, she usually ends up feeding all of the family and most of the neighborhood.

Her most famous dishes are banana pudding, fried deer steak, sticky frog legs, and this crawfish pie, which is essentially the Cajun version of a chicken pot pie.

“I was raised in my grandma’s kitchen. My first memories are right there in that kitchen—learned how to do everything right there. I loved it from the very start. Food is the language, and I know how to speak it.” —Kay Robertson

Crawfish Pies

These pies are perfect for a crowd. If you have fewer folks to feed, freeze one of the pies, unbaked, for later. You can thaw it in the refrigerator overnight and bake as directed when you’re ready.

Makes 2 (9-inch) pies (8 servings each) Hands-On Time 30 min. Total Time 1 hour, 45 min.

2 Tbsp. butter

2 Tbsp. olive oil

1 3/4 cups diced green bell pepper

1 cup diced white onion

1/2 cup diced celery

1/4 cup chopped green onions

8 garlic cloves, chopped

1 1/2 Tbsp. cornstarch

1 (5-oz.) can evaporated milk

3 lb. peeled crawfish tails*

1 (10 3/4-oz.) can cream of mushroom soup

1 Tbsp. Cajun seasoning

1/2 tsp. table salt

1 tsp. black pepper

Pastry for 2 (9-inch) double-crust pies or 2 (14.1-oz.) packages refrigerated piecrusts

1 large egg, lightly beaten

1. Preheat oven to 350°. Melt butter with olive oil in a large cast- iron skillet over high heat. Add bell pepper and next 3 ingredients; cook, stirring occasionally, 8 minutes or until tender and starting to brown. Add garlic; cook 1 minute. Mix cornstarch with evaporated milk; add to skillet. Reduce heat to medium. Stir in crawfish and cream of mushroom soup; cook, stirring constantly, 3 minutes or until thickened. Remove from heat; stir in Cajun seasoning, salt, and pepper.

2. Fit 1 piecrust into each of 2 (9-inch) pie plates. Prick bottom and sides of piecrusts with a fork. Divide crawfish mixture between pies. Cover with remaining piecrusts; fold edges under, and crimp, sealing to bottom crust. Cut slits in top for steam to escape. Brush piecrusts with egg.

3. Bake at 350° for 45 minutes or until golden brown. Let stand 30 minutes before serving.

Note: You can use frozen pre-cooked crawfish tails or peeled shrimp for the crawfish.

Crawfish Étouffée

You’ll need 6 to 7 lb. cooked whole crawfish for 1 lb. of hard-earned crawfish tail meat. You can also substitute frozen, cooked, peeled crawfish tails.

Makes 4 to 6 servings Hands-On Time 25 min. Total Time 35 min.

1/4 cup butter

1 medium onion, chopped

2 celery ribs, chopped

1 medium-size green bell pepper, chopped

4 garlic cloves, minced

1 large shallot, chopped

1/4 cup all-purpose flour

1 tsp. table salt

1/2 tsp. to 1 tsp. ground red pepper

1 (14 1⁄2-oz.) can chicken broth

1/4 cup chopped fresh parsley

1/4 cup chopped fresh chives

2 lb. cooked, peeled crawfish tails

Hot cooked rice

Garnishes: chopped fresh chives, ground red pepper

1. Melt butter in a large Dutch oven over medium-high heat. Add onion and next 4 ingredients; sauté 5 minutes or until tender. Add flour, salt, and red pepper; cook, stirring constantly, until caramel colored (about 10 minutes).

2. Add broth and next 2 ingredients; cook, stirring constantly, 5 minutes or until thick and bubbly. Stir in crawfish; cook 5 minutes or until thoroughly heated. Serve with rice.

Hot Crawfish Dip

In Louisiana, February means two things: Mardi Gras and crawfish. Two-thirds of all mudbugs are harvested in February. Most locals start with a boil. What’s leftover goes into crawfish étouffée, crawfish pie, and luscious appetizer dips like this one.

Makes 8 to 10 servings Hands-On Time 30 min. Total Time 30 min.

1/2 cup butter

1 bunch green onions, sliced (about 1 cup)

1 small green bell pepper, diced

1 (1-lb.) package frozen cooked, peeled crawfish tails, thawed and undrained

2 garlic cloves, minced

1 (4-oz.) jar diced pimiento, drained

2 tsp. Creole seasoning

1 (8-oz.) package cream cheese, softened

Toasted French bread slices

Garnishes: sliced green onion, chopped flat-leaf parsley

1. Melt butter in a Dutch oven over medium heat; add green onions and bell pepper. Cook, stirring occasionally, 8 minutes or until bell pepper is tender. Stir in crawfish and next 3 ingredients; cook, stirring occasionally, 10 minutes. Reduce heat to low. Stir in cream cheese until mixture is smooth and bubbly. Serve with toasted French bread slices.

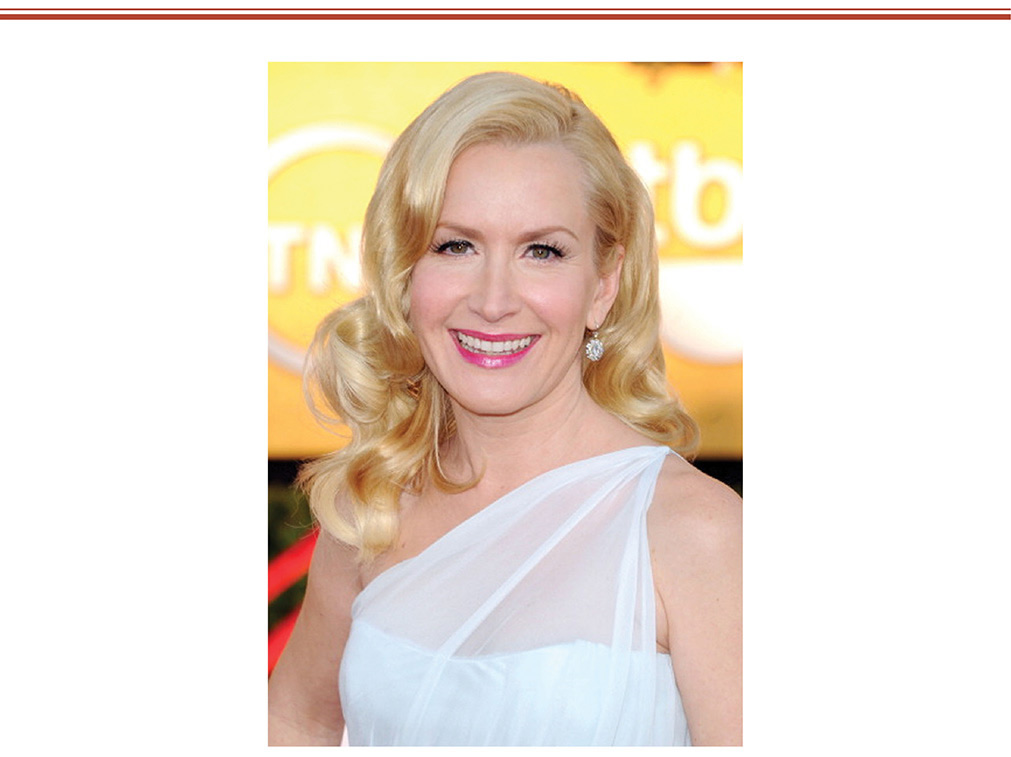

Meet Actress

Angela Kinsey

This fictional Angela Martin is also so diminutive in size that Steve Carrell’s character, Michael Scott, compares her to “a grain of rice.”

In real life, however, Kinsey is upbeat and larger-than-life hilarious. She got her start in the acting world through her involvement in various improvisational and sketch comedy troupes, including The Groundlings and The Improv Olympic Theater.

Kinsey was born in Lafayette and into a family of good cooks. They moved to Indonesia for her father’s job when she was a small child, came back to the States in her early teens, and settled in north Texas. Kinsey has a killer Texas-Louisiana accent to prove it, plus a trove of recipes from her mom, Bertie.

“I totally rely on my mom, Bertie, for recipes and inspiration. I’m learning to cook. It’s hard to eat out with a 2-year-old, and I’m not going to be a takeout mom.” —Angela Kinsey

Bertie’s Corn Casserole

Makes 8 servings Hands-On Time 15 min. Total Time 40 min.

1 Tbsp. butter

1/2 large onion, finely chopped

1/2 green bell pepper, finely chopped

4 cups cooked long-grain rice

2 cups drained canned whole kernel corn

1 3/4 cups (7 oz.) shredded sharp Cheddar cheese, divided

1 1/2 tsp. table salt

1/2 tsp. freshly ground black pepper

3/4 cup milk

1 large egg

1. Preheat oven to 350°. Melt butter in a medium nonstick skillet over medium-high heat; add onion and bell pepper, and sauté 5 minutes or until tender. Transfer to a large bowl; add cooked rice and corn. Mix well. Add 1 1/2 cups shredded cheese, salt, and pepper. Mix all together. Whisk together milk and egg; stir into rice mixture.

2. Spoon into a lightly greased 2-qt. baking dish, and sprinkle with remaining 1/4 cup cheese. Bake at 350° for 25 minutes or until thoroughly heated.

~ A Recipe from a Local ~

Creole Bread Pudding with Bourbon Sauce

This bread pudding is from New Orleans chef Leah Chase, the “Queen of Creole Cuisine.” And yes, it does call for 5 Tbsp. of vanilla extract!

Makes 10 to 12 servings Hands-On Time 20 min. Total Time 1 hour, 15 min.

2 (12-oz.) cans evaporated milk

6 large eggs, lightly beaten

1 (16-oz.) day-old French bread loaf, cubed

1 (8-oz.) can crushed pineapple, drained

1 large Red Delicious apple, upeeled and grated

1 1/2 cups sugar

1 cup raisins

5 Tbsp. vanilla extract

1/4 cup butter, cut into 1⁄2-inch cubes and softened

Garnish: fresh currants

1. Preheat oven to 350°. Whisk together evaporated milk, eggs, and 1 cup water in a large bowl until well blended. Add bread cubes, stirring to coat thoroughly. Stir in pineapple and next 4 ingredients. Stir in butter, blending well. Pour into a greased 13- x 9-inch baking dish.

2. Bake at 350° for 35 to 45 minutes or until set and crust is golden. Remove from oven, and let stand 2 minutes. Serve with Bourbon Sauce.

3 Tbsp. butter

1 Tbsp. all-purpose flour

1 cup whipping cream

1/2 cup sugar

2 Tbsp. bourbon

1 Tbsp. vanilla extract

1 tsp. ground nutmeg

1. Melt butter in a small saucepan over medium-low heat; whisk in flour, and cook, whisking constantly, 5 minutes. Stir in cream and sugar; cook, whisking constantly, 3 minutes or until thickened. Stir in bourbon, vanilla, and nutmeg; cook, whisking constantly, 5 minutes or until thoroughly heated.

Chef Leah Chase, Dooky Chase’s Restaurant

New Orleans, Louisiana

Bananas Foster Upside-Down Cake

The flaming wonder invented in New Orleans inspired this upside-down cake, which tumbles from the skillet, perfectly golden and party ready.

Makes 8 servings Hands-On Time 20 min. Total Time 1 hour, 20 min.

1/2 cup chopped pecans

1/2 cup butter, softened and divided

1 cup firmly packed light brown sugar

2 Tbsp. rum

2 ripe bananas

3/4 cup granulated sugar

2 large eggs

3/4 cup milk

1/2 cup sour cream

1 tsp. vanilla extract

2 cups all-purpose baking mix

1/4 tsp. ground cinnamon

1. Preheat oven to 350°. Bake pecans in a single layer 8 to 10 minutes or until toasted and fragrant, stirring once.

2. Melt 1/4 cup butter in a lightly greased 10-inch cast-iron skillet or 9-inch round cake pan (with sides that are at least 2 inches high) over low heat. Remove from heat; stir in brown sugar and rum.

3. Cut bananas diagonally into 1/4-inch-thick slices; arrange in concentric circles over brown sugar mixture. Sprinkle pecans over bananas.

4. Beat granulated sugar and remaining 1/4 cup butter at medium speed with an electric mixer until blended. Add eggs, 1 at a time, beating just until blended after each addition. Add milk and next 2 ingredients; beat just until blended. Beat in baking mix and cinnamon until blended (batter will be slightly lumpy). Pour batter over banana mixture in skillet. Place skillet on an aluminum foil-lined jelly-roll pan.

5. Bake at 350° for 40 to 45 minutes or until a wooden pick inserted in center comes out clean. Cool in skillet on a wire rack 10 minutes. Run a knife around edge to loosen. Invert onto a serving plate, spooning any topping in skillet over cake.

Traditional King Cake

If you like, hide a heat- and food-safe plastic baby (or a raisin or nut) in the dough of this Mardi Gras treat for one lucky (or unlucky) diner to find.

Makes 2 cakes (about 18 servings each) Hands-On Time 30 min. Total Time 2 hours, 30 min.

1 (16-oz.) container sour cream

1/3 cup sugar

1/4 cup butter

1 tsp. table salt

2 (1/4-oz.) envelopes active dry yeast

1/2 cup warm water (100° to 110°)

1 Tbsp. sugar

2 large eggs, lightly beaten

6 to 6 1⁄2 cups bread flour

1/3 cup butter, softened

1/2 cup sugar

1 1/2 tsp. ground cinnamon

Purple-, green-, and gold-tinted sparkling sugar sprinkles

1. Cook first 4 ingredients in a medium saucepan over low heat, stirring often, until butter melts. Set aside; cool to 100° to 110°.

2. Stir together yeast, 1/2 cup warm water, and 1 Tbsp. sugar in a 1-cup glass measuring cup; let stand 5 minutes.

3. Beat sour cream mixture, yeast mixture, eggs, and 2 cups flour at medium speed with a heavy-duty electric stand mixer until smooth. Reduce speed to low, and gradually add enough remaining flour (4 to 4 1/2 cups) until a soft dough forms. Turn dough out onto a lightly floured surface; knead until smooth and elastic (about 10 minutes). Place in a well-greased bowl, turning to grease top.

4. Cover and let rise in a warm place (85°), free from drafts, 1 hour or until dough is doubled in bulk.

5. Punch down dough, and divide in half. Roll each portion into a 22- x 12-inch rectangle. Spread 1/3 cup softened butter evenly on each rectangle, leaving a 1-inch border. Stir together 1/2 cup sugar and cinnamon, and sprinkle evenly over butter on each rectangle.

6. Roll up each dough rectangle, jelly-roll fashion, starting at 1 long side. Place 1 dough roll, seam side down, on a lightly greased baking sheet. Bring ends of roll together to form an oval ring, moistening and pinching edges together to seal. Repeat with second dough roll.

7. Cover and let rise in a warm place (85°), free from drafts, 20 to 30 minutes or until doubled in bulk.

8. Preheat oven to 375°. Bake for 14 to 16 minutes or until golden. Slightly cool cakes on pans on wire racks (about 10 minutes). Drizzle Creamy Glaze evenly over warm cakes; sprinkle with colored sugars, alternating colors and forming bands. Cool completely.

For Cream Cheese-Filled King Cake: Prepare each 22- x 12-inch dough rectangle as directed. Omit 1/3 cup softened butter and 1 1/2 tsp. ground cinnamon. Increase 1/2 cup sugar to 3/4 cup sugar. Beat 3/4 cup sugar; 2 (8-oz.) packages cream cheese, softened; 1 large egg; and 2 tsp. vanilla extract at medium speed with an electric mixer until smooth. Spread cream cheese mixture evenly on each dough rectangle, leaving 1-inch borders. Proceed with recipe as directed.

3 cups powdered sugar

3 Tbsp. butter, melted

2 Tbsp. fresh lemon juice

1/4 tsp. vanilla extract

2 to 4 Tbsp. milk

1. Stir together first 4 ingredients. Stir in 2 Tbsp. milk, adding additional milk, 1 tsp. at a time, until spreading consistency.

It’s one of the largest and most important wading-bird rookeries in the country. Scientists believe it was formed more than 6,000 years ago, the result of a Mississippi River flood. In 1953 the State of Louisiana encircled its 765 acres with a levee, and now it’s a recreation area—and not just for people. Each spring until about July, some 20,000 herons, ibises, and other long-legged birds nest in the cypress trees and wade the swamps.

Any time of year is good for watching birds at Lake Martin, though. Swamp tour companies offer private tours to make it easy to spot the birds, most of which nest in the 250 acres at the southern end of the lake. We’re talking little and great blue herons, cattle and snowy egrets, black-crowned and yellow-crowned night herons—plus songbirds such as warblers, vireos, grosbeaks, and buntings.

Plenty of gators live here, too. Just ask those swamp guides.

~ A Recipe from a Local ~

Coconut-Almond Cream Cake

If the tops of the layers are a little rounded, level them with a serrated knife. This is a tall cake, and it needs to be level if you want your friends to admire your work before they devour it, as they absolutely will.

Makes 12 servings Hands-On Time 30 min. Total Time 2 hours, 30 min.

2 cups sweetened flaked coconut

1/2 cup sliced almonds

Parchment paper

3 1/2 cups all-purpose flour

1 Tbsp. baking powder

1/2 tsp. table salt

1 1/2 cups unsalted butter, at room temperature

1 1/4 cups granulated sugar

1 cup firmly packed light brown sugar

5 large eggs

1 cup whipping cream

1/3 cup coconut milk

1 Tbsp. vanilla extract

1 Tbsp. almond extract

1. Preheat oven to 325°. Bake coconut in a single layer in a shallow pan 6 minutes. Place almonds in a single layer in another shallow pan; bake, with coconut, 7 to 9 minutes or until almonds are fragrant and coconut is lightly browned, stirring occasionally.

2. Line 3 (9-inch) round cake pans with parchment paper. Grease and flour paper. Sift together flour, baking powder, and salt in a very large bowl.

3. Beat butter at medium speed with a heavy-duty electric stand mixer until creamy; gradually add sugars, beating until blended. Beat 8 minutes or until very fluffy, scraping bottom and sides of bowl as needed. Add eggs, 1 at a time, beating well after each addition (about 30 seconds per egg). Stir in whipping cream and next 3 ingredients.

4. Gently fold butter mixture into flour mixture, in batches, just until combined. Pour batter into prepared pans. Bake at 325° for 30 to 32 minutes or until a wooden pick inserted in center comes out clean. Cool in pans on wire racks 10 minutes; remove from pans to wire racks, and cool completely (about 1 hour).

5. Place 1 cake layer on a serving plate. Spread half of chilled Coconut-Almond Filling over cake layer. Top with 1 layer, pressing down gently. Repeat procedure with remaining half of Coconut-Almond Filling and remaining cake layer. Gently spread Coconut-Cream Cheese Frosting on top and sides of cake. Press toasted coconut onto sides of cake; sprinkle toasted almonds on top.

Coconut-Almond Filling

This filling is the glue that holds the layers together. It works best when chilled, so be sure not to skip that step.

Makes 3 cups Hands-On Time 10 min. Total Time 8 hours, 15 min.

2 Tbsp. cornstarch

1 tsp. almond extract

1 1/4 cups whipping cream

1/2 cup firmly packed light brown sugar

1/2 cup unsalted butter

2 1/4 cups loosely packed sweetened flaked coconut

1/4 cup sour cream

1. Stir together cornstarch, almond extract, and 2 Tbsp. water in a small bowl.

2. Bring whipping cream, brown sugar, and butter to a boil in a saucepan over medium heat. Remove from heat, and immediately whisk in cornstarch mixture. Stir in coconut and sour cream. Cover and chill 8 hours.

2 (8-oz.) packages cream cheese, softened

1/2 cup unsalted butter, softened

2 cups powdered sugar

1 Tbsp. cream of coconut

1 tsp. vanilla extract

1. Beat cream cheese and butter at medium speed with an electric mixer until creamy. Gradually add powdered sugar, beating at low speed until blended. Increase speed to medium, and beat in cream of coconut and vanilla until smooth.

Brooks Hamaker

New Orleans, Louisiana

Say

‘Praline’

Like a Local

It’s a freeform candy, meaning that instead of being poured into a mold, it’s poured onto a baking sheet while hot and allowed to harden in any old shape. Pralines are sold on the street, in drugstores, and in candy shops in the French Quarter and far beyond.

Legend has it that Ursuline nuns from France brought a recipe for almond candy when they came to New Orleans in 1727, but finding no almonds, they improvised with local pecans.

You’ll find similar confections today in France and Belgium and Luxembourg, but nowhere else in the world are they pronounced the way that they are in New Orleans: “prah-lean.”

Café au Lait Pecan Pralines

Makes 2 dozen Hands-On Time 35 min. Total Time 1 hour, 20 min.

2 cups pecan halves and pieces

3 cups firmly packed light brown sugar

2 Tbsp. instant coffee granules

1 cup whipping cream

1/4 cup butter

2 Tbsp. light corn syrup

1 tsp. vanilla extract

Wax paper

1. Preheat oven to 350°. Bake pecans in a single layer in a shallow pan 8 to 10 minutes or until toasted and fragrant, stirring halfway through. Cool completely (about 15 minutes).

2. Meanwhile, bring brown sugar and next 4 ingredients to a boil in a heavy Dutch oven over medium heat, stirring constantly. Boil, stirring occasionally, 6 to 8 minutes or until a candy thermometer registers 236° (soft ball stage). Remove sugar mixture from heat.

3. Let sugar mixture stand until candy thermometer reaches 150° (20 to 25 minutes). Stir in vanilla and pecans using a wooden spoon; stir constantly 1 to 2 minutes or just until mixture begins to lose its gloss. Quickly drop by heaping tablespoonfuls onto wax paper; let stand until firm (10 to 15 minutes).

Vieux Carré

Offer this classic 1930s cocktail after dinner. Vieux Carré (voo cah-RAY) means “old square,” a reference to the French Quarter.

Makes 1 serving Hands-On Time 5 min. Total Time 5 min.

Crushed ice

2 Tbsp. (1 oz.) rye whiskey

2 Tbsp. (1 oz.) cognac

2 Tbsp. (1 oz.) sweet vermouth

1 tsp. Bénédictine liqueur

2 dashes Peychaud’s bitters

2 dashes Angostura bitters

Lemon twist or lemon peel strip

1. Fill 1 (8-oz.) glass with crushed ice. Pour rye whiskey and remaining ingredients into glass; stir. Top with a lemon twist or lemon peel strip. Serve immediately.