The chimes of Big Ben announced to London that it was two o’clock in the morning. At this cold moment in February, a pea-soup fog had fallen over the city, obscuring early morning traffic on the Thames. Prostitutes still walking the streets of Soho, in what is known as “the desperate hour,” referred to it as “Jack the Ripper” weather.

In a black sedan, a doctor, Charles Huggenheim, sped rapidly north through nearly deserted streets. He was heading for Hampstead, where an urgent call had summoned him to the house of an American couple. A former stage actress was about to give birth.

With the screech of his brakes, the doctor parked and rushed to an open door at 8 Wildwood Road in Golders Green, where two anxious men stood. He did not have time to determine which one was the father, as the nanny directed him up the steps where the sounds of pain led him to the master bedroom.

A little baby girl, weighing 8½ pounds, entered the world at exactly 2:30 that morning. It was a relatively smooth delivery. Before the baby was born, the mother had told him, “Two years ago I had a boy. He was called a Botticelli angel. I know this one, boy or girl, will be even more beautiful.”

Almost immediately after the delivery, Sara fell into a deep sleep. She didn’t even see the child before the nanny took her away.

Dawn had broken across the London Heath before Sara woke up. The morning sun had chased away the nightmarish fog.

On her left, her husband, Francis Taylor, held her hand. “You’ve come through, precious one,” he said in a soft voice. On his right, Victor Cazalet, a conservative Member of Parliament, held her other hand. “The three of us have a healthy baby daughter,” he told her, squeezing her hand.

Francis was her husband, Victor was her lover. Not only that, but Victor was also the lover of her husband. She’d never known that any two men could be that devoted to each other. As only her closest confidants were aware, she did not really know which one was the father of her newborn.

In a weak but determined voice, she said, “For appearance’s sake, Francis will be the father. As for you, Victor, we’ll make you the godfather. I know that both of you will love the girl like she was your own blood.” After receiving assurances from both men, she asked them, “Would you please bring in our little girl?”

Francis went for the infant in the nursery. While he was gone, Victor leaned over and kissed Sara on the lips.

“Oh, my darling man, you’ve given Francis and me such a wonderful life. You’ve made us a part of your world. You’re the only person Francis has ever loved. He’s devoted to you and your every wish. I, too, love you with all my heart. I know you’ll bestow your love on our beautiful daughter and take care of her, too.”

“That I promise, and I don’t have to tell you and Francis that I’m a man of my word.”

As he was saying that, Francis came back into the bedroom, holding the newborn girl swaddled in a pink blanket. At bedside, he stood beside Victor, giving him a long, lingering kiss. “Okay, Daddy, present our girl to its mother.”

Victor very gently took the baby and lowered her to Sara’s outstretched arms. “May I present Elizabeth Rosemond Taylor Cazalet?” he asked.

The morning sun streaming in had brightly lit the bedroom. Sara reached for her newborn, taking her in her protective arms.

For the first time, she gazed lovingly into her baby’s face. Suddenly, her own face became one of shock and horror. “Take her away!” she shouted at Victor. “It’s not my daughter. The hairy little thing is the newborn of a money at the zoo!”

Victor quickly retrieved the bundle and passed her immediately to Francis, who carried her from the bedroom back to the nursery and the nanny.

“The doctor assured me she won’t always look that ghastly,” Victor said. “In a few months, all that hair will fall from her body—at least that’s what happens in most cases. Nature itself will cure these genetic defects.”

The cries coming from the nursery sounded more like a screaming rage.

Only a handful of people took note of the historic date of February 27, 1932, and that birth of this ghoulish little girl. But this pathetic little creature with a head far too big for its narrow shoulders would eventually be hailed as “the world’s most beautiful woman.”

A lifetime of tragedy and triumph awaited her in the more than seven decades that followed, decades that would evolve into a new millennium not yet born.

Elizabeth Taylor would both enchant and appall the world she’d so awkwardly entered.

Besides her unusually colored eyes—a curious shade of violet—she would become known for her breasts. A Welsh actor and her future husband, Richard Burton, would refer to them as “apocalyptic. They will topple empires before they wither!”

***

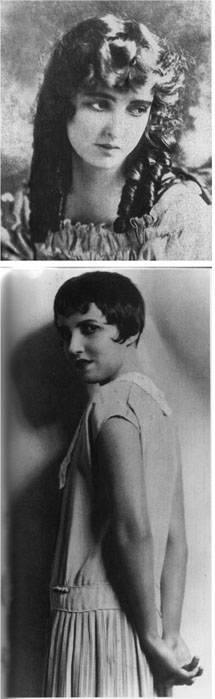

When Elizabeth Taylor became an international star, Sara vicariously lived her daughter’s life. Stardom had been the dream of Sara herself.

Born Sara Viola Warmbrodt on August 21, 1896, she was the daughter of Samuel Warmbrodt, an émigré laundry manager who’d been trained as an engineer. In the milltown of Arkansas City, Kansas, he’d married Anna Elizabeth Wilson, a talented singer and pianist, whose own dream of an artistic career had been abandoned when she became a housewife.

By the time Sara was only eight years old, Samuel claimed that his beautiful daughter had a “bloodthirsty ambition.” Dropping out of high school, she set out to pursue her goal, taking the train to Los Angeles and changing her name to Sara Sothern, “because it will look better on a theater marquee.”

In California, she met a “swishy actor” [her words], Brooklyn-born Edward Everett Horton, who had established a stock company presenting theatrical performances in Pasadena. He would become famous in the movies of the 1930s, for which he was known for saying, “Oh, dear,” in numerous films. His face, with its beaked nose, looked “in perpetual pain,” as the critics said, and he had a jittery voice.

Horton cast Sara in a minor role in The Sign on the Door (1922), a play by Channing Pollock. In 1929, the drama would be adapted for the screen and retitled The Locked Door. It included a role for Barbara Stanwyck as one of her first films.

Pollock was so impressed with Sara’s acting that he cast her in a key role in his next play, The Fool, (1922-23). She played a fifteen-year-old crippled girl, Mary Margaret, a modern-day interpretation of Mary Magdalene. The play was about faith healing, which appealed to Sara, who had been brought up by her mother as a Christian Scientist. At the finale, a crippled Sara throws her crutches away and shouts, “I kin walk!”

The critics attacked it, but evangelical audiences adored it. The play received so much attention that it attracted Alla Nazimova as a member of the audience. Nazimova was enjoying a brief reign as “The Queen of MGM” in spite of her gunboat feet and pumpkin-shaped head. Born in the Ukraine, she lived in a mansion on Sunset Boulevard called “the Garden of Alla.”

Backstage, after one of Sara’s performances, Nazimova swept down like a bird of prey onto the more innocent Sara, dazzling her with her appearance in a peacock gown. “I saw a brilliant actress in the making on the stage tonight,” she told Sara.

By that weekend, Sara was living with Nazimova at the Garden of Alla. The movie queen was known for seducing young women. Some of her earlier involvements had included sexual and emotional flings with Natacha Rombova, wife of Rudolph Valentino, and Dolly Wilde, the niece of Oscar Wilde, described as “the only Wilde who likes women.”

Nazimova arranged a screen test at MGM for Sara, which she directed herself. Although at the time, she still had considerable influence, no director found Sara worth even a minor role in any of their silent films.

Through Nazimova, Sara met her first “beau,” Franklin Pangborn, a member of Nazimova’s stage company. The effeminate actor would enjoy a long career in films, becoming known for his droopy puss and his “hands on his hips” style of acting, indicating his disapproval of the antics being played out before him. Critics called him “the screen’s most effete fussbudget.”

There couldn’t have been much of a romance between Sara and Pangborn, as he was known as one of Hollywood’s most stately homos. Nazimova disapproved of the relationship. “What do you want with that mincer? My more masculine actors go to his dressing room for fellatio.”

By modern standards, Pangborn is hailed as “a gay stereotype of the 1930s.” Over the years, Sara occasionally encountered him in Hollywood. The actor lived in Laguna Beach with his devoted mother and his partner, Gavin Gordon.

As the years went by, Sara would have a number of discreet affairs with women, although she confined most of her adulterous relationships to men.

Nazimova liked to dominate her young protégées, and Sara was a very self-determined woman with an independent streak.

When an offer arrived to star opposite James Kirkwood, Sr. on Broadway for a repeat of the role she had played in The Fool, Sara told Nazimova goodbye and took the train East.

Kirkwood had made his film debut in 1909, and was both a director and an actor, playing leads for D.W. Griffith and later directing Mary Pickford, who also became his lover. Before his death in 1963, he would be involved with more than two hundred films, either as an actor or as a director.

[Ironically, Kirkwood Srs.’ son, James Kirkwood, Jr., would one day write a novel, There Must Be a Pony, in which Elizabeth would star, in 1986, for Columbia TV, opposite Robert Wagner, her former lover.]

Critics labeled The Fool as “religious buncombe” and even attacked the audiences who went to see it. “Their favorite tune is Onward, Christian Soldiers,” wrote one columnist. In time, however, five million devout believers would attend performances of The Fool.

The play became so successful that it was taken to London, opening in September of 1924 at the Apollo Theatre, starring Henry Ainley, the lover of a very young Laurence Olivier. Sara retained her role as the crippled girl. The critic for The Times attacked it as a “religious orgy.”

On Sara’s free night, she went to see “the toast of London,” Miss Tallulah Bankhead, starring with Nigel Bruce and C. Aubrey Smith in The Creaking Chair. The noted playwright, Emlyn Williams, said of Tallulah’s voice, “It is a timbre steeped as deep in sex as the human voice can go without drowning.” Sara came backstage to congratulate Tallulah on her performance, and they were seen an hour later driving out of town together in Tallulah’s new emerald-green and cream-colored Talbot Coupe, heading to a country house in Surrey that C. Aubrey Smith allowed Tallulah to use for sexual trysts.

Sara arrived at the theater the following night “a little worse for wear.”

Ironically, Sara’s future daughter, Elizabeth, would take over roles previously performed on Broadway by her mother’s lover, Tallulah.

Later in life, when Francis Taylor met Tallulah, the outspoken Alabama belle said to him, “I’ve had your wife. You’re next!”

During her London stay, although Sara did not build up the massive lesbian cabal of fans that Tallulah did, numerous female admirers awaited outside the theater door for a glimpse of her every night.

As the playwright, Channing Pollock said, “These baritone babes were clamoring for bits of Sara’s frock or locks of her hair as souvenirs.”

When The Fool closed in London, Sara went back to New York, where her career wound down as she appeared in one flop after another. In the late summer of 1925, she starred on Broadway as Colette in The Dagger, a play which critic Alexander Woollcott defined as “childish rubbish.”

Meanwhile, Pollock had written a new play called The Enemy, and Sara desperately wanted to play the lead. But Pollock preferred Fay Bainter instead. Sara sent him what Pollock later called “the most vulgar, venomous, and vicious letter in the history of the theater.” Perhaps daughter Elizabeth inherited her famous potty mouth from her mother.

In October of 1925, Sara appeared in a featherweight musical called Arabesque. Bela Lugosi was ridiculously cast as a lecherous sheik, for which he was laughed off the stage. But in 1931, he made a marvelous film comeback as Dracula.

Three days before Christmas of 1925, Sara opened in Fool’s Bells, which ran for five nights. It was a fantasy in which she played a character trying to bring solace to a hunchback, evocative of Charles Laughton in The Hunchback of Notre-Dame. Unwilling to abandon her hopes of working as an actress, she made two more attempts at stardom, opening on February 22, 1926 in Mama Loves Papa, a matrimonial farce that was ridiculed in the press. Her final stage appearance was in August of 1926 when she starred in a pallid comedy called The Little Spitfire. It sputtered out at Broadway’s Cort Theater.

By then, Sara had decided that she wanted to play another role—that of the wife of a successful man. Nearing thirty, she went with her roommate, Leatrice Loyale, to El Morocco, a nightclub where wealthy clients pursued showgirls.

In the club, she was seated two tables away from a handsome man about her own age and an older, distinguished-looking gentleman who appeared to be his patron, possibly his lover. She studied the younger man’s face carefully, as it looked familiar. She finally concluded that it was Francis Taylor, whom she’d known back in Arkansas City.

Tugging at her roommate’s sleeve, she said, “The night is young, but I’m getting older every minute. Let’s go over to that table and say hello to these guys. I know the younger one. He doesn’t know it yet, but I’m going to marry him.”

***

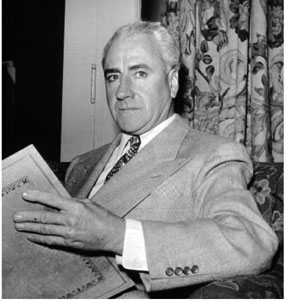

Francis Lenn Taylor, who may have been the father of Elizabeth, was born in Springfield, Illinois on December 18, 1897, the son of Francis Marion Taylor and Elizabeth Mary Rosemond. Later, his parents moved to Arkansas City, Kansas. To earn a living, the senior Francis became what was known at the time as “a commercial gent” (i.e., a traveling salesman). Eventually, he left the road to settle down in Arkansas City, where he opened a lucrative private express mail messenger service.

Young Francis inherited the good looks of his tall, rugged father, who had a bloodline that was both Scottish and Irish. Unlike his more outgoing father, the son was shy and introverted.

In school, many girls found him very good-looking and tried to strike up a conversation with him. He was polite but definitely not interested. Any free time he had was spent with football hero Randolph Parrafin, whom he affectionately called “Randy.” Three years older than Francis, Randy had almost a devoted slave in Francis, who spent whatever money he had on presents for the football athlete. On many days, Randy ate both his own packed lunch and part of Francis’ paper-bagged lunch as well.

One summer, Randy took Francis for a six-week camping trip through the Ozarks. But for his senior year, he dumped Francis and took up with the school’s beauty queen, Marcia Rothermere. Randy had no more time for Francis. After he was graduated from school, the older boy married Marcia and moved with her to Kansas City.

Sara, a year older than Francis, befriended him. Romance didn’t seem a factor. Sara seemed to console Francis, as each of them plotted various ways to get the hell out of this bleak Kansas landscape. Each of them dreamed of life in Hollywood or New York.

Sara was the first to leave, abandoning Francis, who felt lonelier than ever. But he was rescued by the arrival of his uncle, Howard Young. Uncle Howard was a rich art collector, who had married Mabel Rosemond, the younger sister of Francis’ mother.

Howard had made a small fortune from his lucrative business of retouching and tinting family photographs and selling them in gold-colored oval frames. With the profits, he’d invested in the booming oil well business of Texas and Oklahoma.

Newly rich, he’d opened an art gallery in St. Louis, specializing in Old Masters from Europe, which he sold to the nouveaux riches of the Middle West. For some reason, Howard took to Francis, virtually adopting the sixteen-year-old. “He became like the son I never had,” Howard said. “When you looked into the sparkling blue eyes of his, the day was yours. He was a handsome and charming boy, but he knew nothing of art. I talked to him about art for hours at a time, and he absorbed everything I said like a sponge.”

Before Howard ended his family visit, he’d convinced Francis to drop out of school and go to St. Louis with him as his secretary.

Francis’ parents were jealous that Howard had taken their son from them, but his mother said, “Howard can give you all the advantages in life we can’t.”

The father was more cynical. “There’s something about your brother…well, something unnatural,” he said to his wife. “I can’t put my finger on it.”

“Don’t be a silly old goose.” Elizabeth Mary responded. “Howard was always artistic.”

Francis learned how to run an art gallery so quickly that Howard invited him to come and live with him in New York, and help him operate the Howard Young Art Gallery at 620 Fifth Avenue.

As an art dealer, Francis was an immediate success. Many of his older women clients preferred to be waited on by him, and he was often presented to their eligible daughters, but he showed no interest,.

Howard objected to the nights when Francis would disappear into the taverns of Greenwich Village, often not arriving back home until nearly dawn.

Francis admired his uncle and listened to stories of how he’d come out of Ohio, arriving in New York without a penny. By the time he was eighteen, he’d accumulated half a million dollars, which was a fabulous fortune in those days. Eventually, he found himself in the position of selling Old Master paintings to the Ford and Fisher families of Detroit.

At the time of Howard’s death in 1972, he left an estate of $20 million, none of which went to Elizabeth. He claimed that his movie star relative already knew how to make her own money.

When he wasn’t working, Francis lived in luxury, visiting his uncle’s vacation homes in Westport, Connecticut, and in Minocqua, Wisconsin. In winter, he made frequent visits to Howard’s mansion on Star Island, Florida. Various young men from New York also accompanied him on his vacation trips. On one trip to Florida, Francis met one of Howard’s closest friends, Dwight D. Eisenhower.

Back in New York, Howard told Francis that he wanted to expand his galleries and was negotiating for a location in the exclusive Mayfair district of London. He wanted Francis to manage it, but only if he’d break from running around with a “rough gang of boys from the Village” and take a wife, presumably as a means of settling into marital bliss. “As the director of a major gallery in Mayfair, you must look very respectable to the rich Brits who are investing thousands of dollars in a piece of art,” Howard advised.

That night, Howard invited Francis to El Morocco to celebrate. With the challenge of a marriage in front of him, Francis was dressed immaculately for the occasion, sporting a pair of horn-rimmed glasses and a well-tailored suit in midnight blue with gray pin stripes.

When Sara and her friend, Leatrice, came over, Francis, of course, remembered her from their days together in Arkansas City. Both Sara and Francis had changed and matured.

At first, after learning that she was an actress, Howard objected to Sara, even though she told him that she was giving up the theater.

Sara and Francis resumed the friendly intimacy they’d enjoyed as teenagers, and began to date each other after their reunion at El Morocco. He took her to the theater, to art exhibitions, and for long walks in Central Park. The pressure to marry was strong for Francis, who talked it over with Sara. In fairness to her, he warned her that it might be a marriage based on love and respect, but she was told not to expect passion—“Perhaps sex every three months or so.” Attracted to the idea of the good life he held out for her, and having no other career options, she eventually accepted his proposal of marriage.

They were married at the Fifth Avenue Presbyterian Church, with Howard standing in as best man. The date was October 23, 1926.

After a brief honeymoon, the couple moved into a Manhattan apartment Howard rented for them at 55 West 55th Street.

Sara was dazzled to learn that Howard was going to finance a three-year honeymoon for them. With the understanding that the newlyweds would be based in London, Howard would orchestrate, and pay for, an extended tour of the capitals of Europe, including Budapest, Paris, Rome, Vienna, Berlin, Florence, and Venice. They were instructed to purchase Old Master paintings, with the understanding that they’d be shipped back to New York, where Howard would peddle them to wealthy art collectors at inflated prices.

Sara by now had informed Francis that within the confines of their marriage, she would be the boss. When she became angry with him, she reminded him that she could have been a great star had she not abandoned the theater to marry him.

During their long, drawn-out honeymoon, Sara spent many a night alone in her hotel suite, as Francis sampled the night life of various capitals, often in the company of handsome young men.

On one occasion, Howard joined the newlyweds in Paris. His nephew was candid in his confession, telling his uncle that he was experiencing sexual difficulties with Sara. “I find men exciting, but I am not excited by the female body, except when it is depicted in art. We do go to bed on occasion, but it is not something I look forward to.”

One of their sexual unions was fruitful, however. When Sara and Francis settled more permanently in London, she announced that she was pregnant.

After settling into an unsuitable residence, Sara found her dream house on the edge of Hampstead Heath. She recorded in her diary that in the yard, “the tulips were almost three feet high, with forget-me-nots, yellow and lavender violas, flaming snapdragons, rich red wallflowers, and a formal rose garden terraced down to the Heath.”

Their first child, a startlingly beautiful boy, was born in 1929. They named him Howard in honor of their patron, Howard Young.

At 35 Old Bond Street, Francis had immediate success with his art gallery, often catering to rich American tourists visiting London. Among less important work, he was selling paintings by Constable, Reynolds, and Gainsborough.

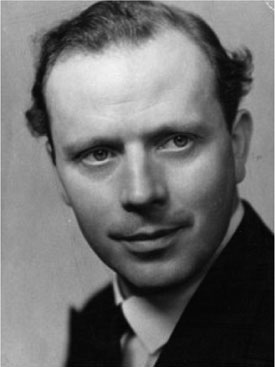

One slow, rainy afternoon, a handsome, gregarious bachelor, politician, sportsman, and art collector came into Francis’ gallery. He seemed to exude charm.

“Mr. Taylor, I presume,” he said in a cultured, aristocratic British accent. “I am Victor Cazalet. I collect art.” He paused, studying Francis carefully. “And other things that amuse me.”

***

Those who believe in love at first sight can point to Francis Taylor and Victor Cazalet to prove their case. Victor admired the paintings in Francis’ gallery so much he purchased three valuable ones that afternoon. Victor’s political enemies also spread the rumor that he purchased Francis, too.

After Francis closed the gallery, he had drinks with Victor at The Dorchester, followed by a lavish dinner at a private supper club in Mayfair. Francis called Sara, telling her that he wouldn’t be home that night, as he was spending it with a very important new client.

At Victor’s flat the following morning, his butler served his boss and Francis breakfast. Francis was attired in one of Victor’s satin robes. Apparently, the conservative Member of Parliament and the art dealer found in each other what each of them had been searching for for such a long time. From that morning forth, until World War II drove them apart, Victor and Francis became almost inseparable.

That night the two new lovers dined with Sara in Mayfair, Victor finding her a total delight. He obviously was pleased at how accepting she was of his newly formed relationship with her husband. Victor had a small bisexual streak in him, and soon he was bedding both Francis and Sara, but not at the same time. Most of his nights were spent in the arms of her husband.

“My brother practically adopted Sara and Francis, and they were seen everywhere together,” claimed Victor’s sister, Thelma Cazalet-Keir, who was also a Member of Parliament, one of the first women to occupy such a position. Advanced in thinking and outlook for a woman of her time, Thelma was understanding about her brother’s need for love, either from Francis or Sara. She never disapproved of his friendship with the Taylors, and often spoke of it to family and friends. It is because of her that future Elizabeth Taylor fans have an insight into what was going on before her birth.

Victor introduced both Sara and Francis into the closed door world of tout London, as they met financiers, politicians, the literati, theatrical stars, and the ruling class of lords and ladies. “My brother took Francis everywhere—and sometimes Sara was included,” Thelma said. “They visited great country houses of Victor’s friends. Francis—and Sara, too—got to see a slice of Britain that would more or less disappear when World War II came. Victor lavished presents on Francis, even giving him a red Buick when you didn’t see any red vehicles on the road, except for fire trucks.

Victor stook only five feet three and since childhood had been nicknamed “Teenie.” Even though short of stature, he was a towering figure in Britain, numbering Winston Churchill and Anthony Eden among his closest friends, and Queen Victoria herself as his godmother. When Elizabeth was born, Churchill, at least on one occasion, bounced her on his knee. When she met Eden, she would invite him to ride her favorite horse. The horse objected, tossing the famous British leader into a rose bush.

One morning, Victor invited Francis to a junk shop along Kings Road in Chelsea. It was one of those occasions that happens about as often as the average person wins Lotto.

With his keen eye for art, Francis spotted a portrait of a man which appealed to him. Victor purchased it for him for five pounds.

The next week, Francis called in three experts who examined the picture, Portrait of a Man, and defined it as having been painted by Frans Hals the Elder (c. 1580-1666), a Dutch Golden Age painter who is best known today for his portraits.

The valuable painting, years later, was owned by Francis’ daughter, Elizabeth Taylor, who was advised by art experts to value it at $2.3 million. Portrait of a Man became the cornerstone of her personal collection of world-class masterpieces.

Victor was a close friend of Dame Rebecca West (1892-1983), who was defined by one writer as “the greatest woman since Elizabeth I.” During her youth, West was a fiery suffragette and socialist, and, as she matured, she became one of the foremost publicly famous intellectuals of the 20th Century.

When Victor invited Francis to spend an afternoon with Dame Rebecca, she later said, “Francis was one of the handsomest men I’d ever met—a leonine head, lake-blue eyes, and thick dark lashes that spoke of adventure in faraway lands.”

In the late 1930s, Victor took Francis and their newly born daughter, Elizabeth, to spend an afternoon in the country with Dame Rebecca. Elizabeth always remembered meeting this formidable woman. In later life, after Elizabeth had become a public advocate in the struggle against AIDS, she said, “Dame Rebecca was a kind of role model for me. I decided that before I died, I wanted to be known for something other than collecting diamonds.”

Victor became so enamored of Francis, and of Sara as well, that he presented them with a country home, Little Swallows, which was a fourteen-room, 16th-Century gatekeeper’s lodge located on his 3,000-acre country estate, Great Swifts, near Cranbrook, Kent. The home had been named after the birds that lived outside young Elizabeth’s bedroom window. Locals referred to it as a haunted house, and it was immortalized in the Jeffry Farnols novel, The Broad Highway.

When Howard Young flew to London and learned about Francis’ close relationship with Victor, he invited both young men to go with him on an art-buying spree in Paris. Howard joined them on wild nights on the town, as they patronized such clubs as L’Elephant Blanc, Scheherazade, and Monseigneur.

“Those two couldn’t hold their firewater,” Howard later revealed to his close friends in New York. “They kissed and held hands. They giggled and nibbled ears. They even danced together. Their behavior was acceptable for Paris, but, as I warned them, such antics surely would not be tolerated in Britain, where Victor was a leading member of the Conservative Parliament. What would Winston Churchill say?”

During a visit to Little Swallows, the distinguished art critic, Charles R. Stephens, said, “Victor and Francis were very, very close. One would start a sentence and the other would finish it. It was all too apparent that these two men were in love, but in the art world of London, I was accustomed to such liaisons.”

Allen T. Knots, who worked at the time as an editor at Simon & Schuster in New York, visited Little Swallows as a house guest. “In the middle of the night, I got up to use the bathroom. Out in the hallway, I saw both Victor and Francis chasing after each other. Each of them was totally drunk and jaybird naked. Victor and Francis occupied the master bedroom, and Sara slept in an adjoining room.” This was revealed by Knots to Robert Rhodes James, Victor’s biographer.

Often, Victor was away on some political event. When he was not in London, Francis was seen with a tall, handsome, blonde-haired twenty-year-old, Marshall Baldridge, who worked as his assistant in Francis’ art gallery. Francis was about twenty-five years older than Baldridge

During the late 1930s, Dame Rebecca said, “Victor was a man of great charm, but as an intellect, he was definitely a featherweight. He could be incredibly naïve.” She cited his strong support of General Francisco Franco and his Fascists during the Spanish Civil War.

In Rome, Cazalet said, “I’m very impressed with Benito Mussolini. The government of Italy is a one-man show, and law, order, and prosperity reign supreme today.” In 1937, he visited a concentration camp in Bavaria, and later cited it for being “quite well run with no undue misery or discomfort. The prisoners seemed quite content.”

But after that, just before the outbreak of World War II, Cazalet, along with Winston Churchill, opposed the appeasement of Adolf Hitler by Britain’s Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain. Victor also became the leading exponent in England for the promotion of a Jewish homeland in Palestine. He was most sympathetic to the plight of the Jews throughout history. He wrote, “If I were a Jew, I would cling onto the idea of a sovereign state for all I was worth.”

Often, Victor and Francis preferred to spend weekends in London, with Sara and their son, Howard, stashed in Kent. The two men attended concerts together and often saw plays in the West End.

On one occasion, they met a handsome and charismatic young actor, Laurence Olivier, and became intimate friends with him. A bisexual, Olivier often spent nights with Francis and Victor in their London flat. Olivier’s envious chief rival, John Gielgud, spread stories about how the three young men were involved in a ménage à trois.

When he heard these rumors, Victor denounced Gielgud as “a silly old queen. He’s no doubt jealous that he’s not included.”

During the summer of 1931, Sara prepared a special dinner for Victor and Francis in London at the home near Hampstead Heath. She had an announcement to make.

At the end of the dinner, when the men sat in the library enjoying their brandy, she came in to tell her secret. “I visited the doctor today. We are going to have an addition to our family. Surely no little infant in all the world could be blessed to have two such wonderful fathers.”