Sara Taylor completely distorted her version of Elizabeth’s birth when she wrote an article for McCall’s in 1954. “As the precious bundle was placed in my arms, my heart stood still. There, inside the cashmere shawl, was the funniest looking baby I had ever seen! Her hair was long and black. Her ears were covered with a thick black fuzz and inlaid into the sides of her head. Her nose looked like a tip-tilted button, and her tiny face was so tightly closed it looked as if it would never unfold.”

Sara also declared that Elizabeth went ten days before opening her eyes. “That’s poppycock,” claimed Thelma Cazalet-Keir, Victor’s sister, who had been appointed as the child’s godmother. “I visited the day after the birth. Her eyes were not only wide open, they were as blue as a summer day.”

In time, the child would become celebrated for her violet eyes.

After leaving the Taylor home, Thelma reported back to the Cazalet family. “That is definitely Victor’s child. I think she should be named Elizabeth Taylor-Cazalet.”

The little girl was born with a genetic mutation—distichiasis, aka a double set of eyelashes. Child actor Roddy McDowall would later recall that during the making of Lassie Come Home (1943), the director called out, “Get that girl off the set—she has too much eye makeup on, too much mascara.”

Back in the makeup department, it was ascertained that Elizabeth was wearing no mascara at all. “That double set of eyelashes was the real thing,” Roddy said.

Elizabeth also had a localized form of hypertrichosis, which in the cases of most babies with the condition disappears after they’re three months old. However, in Elizabeth’s case, this chromosomal abnormality would sometimes reoccur, especially on her arms, and she’d have to have excess hair removed by electrolysis. One morning, her then-husband, Richard Burton, said he woke up in the dark and reached for his wife. “Bloody hell, I thought I’d gone to bed drunk with a fucking monkey.”

The excess hair on Baby Elizabeth’s body soon faded away, and she began to be viewed as a very beautiful young girl, except for her big head. When she was old enough to form an opinion of herself, she said, “What a podge! A big head set on a dumpy body.” And although her adult face would be universally applauded, her body often drew mixed reviews.

Her birth in 1932 was registered in the very unfashionable blue collar district of Hendon, bordering chic Hampstead. Years later, Elizabeth would claim that she had been born in Hampstead, although her future husband, Richard Burton, would remind her, “Ducky, you were just a low-rent girl from Hendon.”

As she grew older, her brother Howard called her “Lizzie the Lizard.” From then onward, she always hated to be called “Liz.” All of her friends knew to refer to her as “Elizabeth.” She was furious in 1995 when C. David Heymann published a thick (and well-respected) biography of her and entitled it Liz.

An art patron, Philip Beaver, purchased two valuable paintings from Francis at his Mayfair gallery and was invited back to Golders Green for dinner. He recalled the night. “I saw them socially, and both Sara and Francis looked unhappy. Francis drank a lot. I don’t think he wanted to be a family man. He spent most of the evening talking about Victor Cazalet. There was a story making the rounds of Mayfair that Francis had once been arrested in a gents’ toilet for inappropriate behavior. Their son, Howard, was a classic beauty. I was shown Elizabeth in her cradle. She was a strange little thing, with lashes so long they’d have looked more appropriate on a Soho tart. She still had her baby hair and a thick downy pelt. Who would have thought that such a little creature would grow into one of the world’s most glamorous women?”

As each passing year went by, Elizabeth grew into the dark-haired beauty that she was to become. Victor doted on her, buying her expensive presents. In many way, he seemed more like a father to her than Francis.

When Elizabeth turned three years old, she came down with her most serious illness to date, a harbinger of many afflictions that would haunt her for the rest of her life.

Hearing that she’d been running a fever of 103°, and how desperately ill she was, Victor drove through “buckets of rain” for ninety miles to reach her side. He stayed with her, often sleeping with her in his arms and doctoring her himself, until her fever broke. According to his biographer, Robert Rhodes James, after three weeks by her side, ignoring his commitments, both business and political, he finally left. But he formed a bond with her that would last forever, even beyond his death.

With money provided by both Victor and Howard Young, now back in New York, the Taylor family lived an upperclass life, with a full-time chauffeur, three maids, a private chef, and a nanny. Victor and Francis made frequent commuter flights to Paris, where they bought fashionable frocks “for our little daughter.”

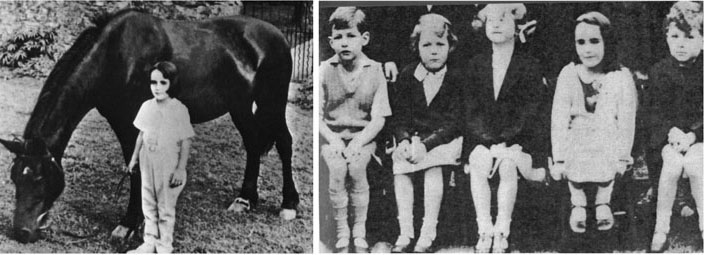

When Elizabeth was old enough, Victor bought her her first horse, which she named “Betty.” She rode it around his 3,000-acre estate. Later, she would claim that, “My greatest happiness as a child was riding Betty through the woodlands of Kent.”

“I had the best of both worlds,” Elizabeth later said. “The lovely countryside of Kent and that beautiful home in London where I would wander through the Heath every afternoon.”

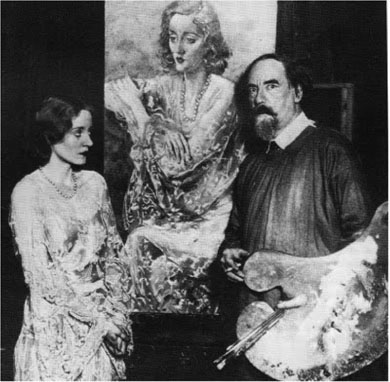

In a touch of irony, the Hampstead house where Francis and Sara lived had previously been owned by Augustus John, the Welsh painter who before World War I was known as the leading exponent of post-Impressionism in Britain.

In London, his work was compared to that of both Matisse and Gauguin. A great deal of his fame rested on his style of portraiture, which was both imaginative and extravagant. By the 1920s, he’d become Britain’s leading portrait painter, interpreting subjects who included T.E. Lawrence (the famous Lawrence of Arabia), Tallulah Bankhead, George Bernard Shaw, and Thomas Hardy.

When Augustus John moved out of his Hampstead house for other digs, he’d abandoned several of his paintings, leaving them still hanging on the walls. Francis seized them as his property and shipped them to New York, where Howard Young sold them at exorbitant prices.

Francis and Victor often visited John, who had a habit of not finishing and discarding paintings that displeased him. Several times, Francis discreetly rescued them from the garbage and quietly sent them to New York where they, too, brought high prices. Francis, in fact, is interpreted today as the dealer who was most instrumental in making John famous among consumers and critics in America.

In spite of Francis’ exploitation of John, the two men became friends. Francis was astonished at John’s “insatiable sexual appetite,” as the artist himself defined his condition. “My appetite has destroyed the women who love me best,” John told Victor and Francis. As art critic Brian Sewell said, “He was driven to draw the women whom he bedded, and bed the women whom he drew.”

Many of John’s drawings were of beautiful nudes. Introduced to Elizabeth when she was six years old, he asked Sara and Francis if he could paint her. Both of them were overjoyed, and so was Victor. However, when Sara learned that Elizabeth would have to pose in the nude, she objected.

Years later, in Hollywood, Elizabeth would express her deep regret. “I should have posed bare ass for Augustus. My God, that painting today would be worth millions.”

When she came of age, Elizabeth attended school at Byron House, which was known for being “snobbish and strict” and reserved for children of only the finest families. She rebelled at the green cotton smock she was forced to wear like the rest of the girls. “I don’t ever want to dress like the rest,” she told her teachers. “When I grow up, I will wear only clothes designed just for me.”

Elizabeth also studied dance at the Vacani Dance School on Brompton Road, run by Pauline Vacani and her daughter, Betty. Years later, in Hollywood, Elizabeth claimed that she attended school with the Princesses Elizabeth and Margaret Rose. But that wasn’t quite true. For the royal sisters, a private instructor was sent to teach dance to the girls at Buckingham Palace. Betty denied that Elizabeth ever studied ballet at the school, as she’d later tell interviewers. “We didn’t teach ballet to girls that young. Elizabeth learned dance routines such as tap, polka, and such social dancing as the waltz.”

Members of the royal family did, however, attend an end-of-semester recital. The Duchess of York (later to become Queen Elizabeth, wife of George VI) attended, bringing the royal daughters, Elizabeth and Margaret Rose. After her presentation, Elizabeth (Taylor), dressed as a butterfly, remained on the stage by herself, curtsying and taking bows until the stage manager was forced to draw the curtain. Sara later recalled the incident. “I had given birth to a ham.”

Before she left England for America, Elizabeth did meet Margaret Rose on two other occasions when they were very young. “She gave me my first cigarette—called a fag—to smoke. I smoked it, or rather choked on it, and we talked about boys. Margaret and I were very advanced for our age, and we were thinking about the opposite sex when most girls our age were still nursing their dolls.”

Sara noticed this early interest in boys. “Elizabeth was maturing too fast.”

Francis told both Victor and Sara, as well as Thelma, that there was no cause for alarm. “Haven’t you heard of childhood sexuality? Five-year-old kids can show an interest in sex. If you don’t believe me, go sign up for a session with Anna Freud. She practices in London and is said to be an expert on child sexuality.”

Elizabeth and Margaret Rose would meet again officially on several more occasions.

In addition to introducing Francis and Sara to leading members of English society and politics, Victor also introduced them to prominent Americans living in London. In 1939, none was more famous than Joseph P. Kennedy, U.S. Ambassador to the Court of St. James’s.

At one point, Victor had suggested to Ambassador Kennedy that he should have his portrait painted by Augustus John. Victor invited Rose Kennedy and the Ambassador for a visit at Francis’ Mayfair art gallery, knowing that he could make the arrangements for such a portrait.

A deal was never struck, but Francis bonded with the Ambassador and Mrs. Kennedy. The expatriate Americans got along so well that the ambassador invited Sara, Francis, and Victor to a lavish party at the American Embassy on Grosvenor Square in Mayfair.

This was reciprocated by an invitation from Victor for the Kennedy family to spend a Sunday at his sprawling estate in Kent. It was on this occasion that a seven-year-old Elizabeth Taylor met the handsome and charismatic John F. Kennedy, who was twenty-two years old at the time.

Elizabeth would often discuss that afternoon with her friends in Hollywood. “I thought Jack was handsome, tall, rich, and on the prowl. For the first time, I cursed myself for being so young. When he flashed that smile at me, I melted.”

JFK and the young Elizabeth went horseback riding together. “I knew he wanted to be spending his Sunday with an older and more beautiful girl, but he was very gracious to me, although I could see that the look in his glazed eyes was far away.”

Elizabeth later said that before the day ended, “I became very bold. Before we got back to Victor’s home for dinner, I said something that must have amused him to no end. I told him that when I grew up, and that would be sooner, not later, I planned to marry him. When he looked at me with a most doubtful expression, I told him ‘Even if you’ve not the kind of man who wants to get married, I plan to make you my boyfriend.’”

“You mean, you and me…lovers?” he asked.

“That’s right. “You and me.”

In spite of her young years, Elizabeth turned out to be clairvoyant.