“Mrs. Yombo!”

An ancient black woman came to the kitchen door. Filaments of smoke trailed from her pipe.

“More rice for Mister Robert,” the priest said.

She came to the long table, took Robert’s bowl, and went back to the kitchen.

The priest filled Robert’s glass with water, his own glass with wine, lit a cigarette, watched Robert lift his foot off the floor and place it on a chair.

“You must drink more water,” the priest said. “The sulfadiazine.”

Robert drank the glass down. Mrs. Yombo came with a bowl of rice and fish. The priest watched Robert spoon the rice into his mouth. He filled the glass from the pitcher and signaled for Robert to drink again.

“They won’t bother whites,” he said. “They didn’t last time.”

“This is Minah’s territory,” Robert said. “If this thing is between Momoh and Minah, there will be fighting.”

“Momoh is too strong for Minah. It will be over quickly. Before it gets bloody. It won’t be like last time.”

“It’s already bloody.” Robert pushed the bowl away. “I’d like to look at your radio.”

“You can fix it?”

“I don’t know. What’s wrong with it?”

The priest shrugged. “It stopped working.”

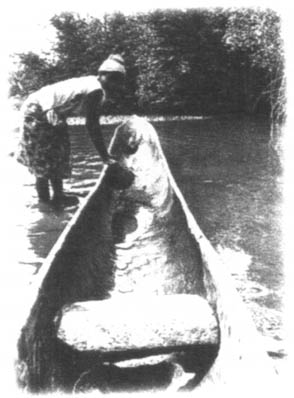

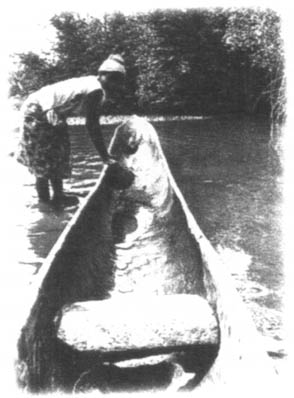

Robert limped across the room to the desk, which was positioned under a wide, iron-barred window that looked out on bare earth sloping down to the landing beach. The dugout remained where he had pulled it ashore. The priest had welcomed him and given him coffee, then sat him down on the bench in the kitchen and cut away the muddy bandage and cleaned the wound. After Robert had showered he gave him the sulfadiazine tablets for the infection, some codeine, bandaged his foot and sat him down to food and questions. Robert had seen the radio as soon as he’d come into the room and had asked to use it and the priest had told him that it was broken. Now he stood looking down at the set.

“What do you need?” the priest asked.

“Screw driver, steel wool, alcohol, cotton swabs.”

Robert lifted the radio off its table and placed it on the desk where he had light from the window. He leaned over it, examined the wires leading down to the battery connectors. The priest went into the kitchen and came back with a small tool box. Robert took a screw driver and began removing the cover.

“I don’t suppose you have a meter?”

“A what?”

“A multimeter.”

The priest shook his head.

“What about the manual?”

The priest shrugged. “I have never seen one.” He watched Robert poke around inside. “What are you doing?”

“Looking for corrosion—it’s the most obvious problem. I need the steel wool and the alcohol.”

The priest went through the kitchen door. Robert pulled a chair up to the desk, sat, removed a circuit board from the radio, examined it, saw nothing unusual. A little corrosion, but no broken solder, no burned places. He put the board on the desk and settled back in the chair to wait for the priest. He raised his hand and touched the side of his face. His ear was still swollen, but the ringing had stopped. He ran his fingers over the stubble of beard. The scabs covering the scores of tiny cuts felt as coarse as his beard.

His gaze wandered to the window. An old woman had landed a dugout next to the one he had stolen and was pulling it up on the muddy shore. She lifted a basket to her head and started up the beach. A young man in dirty shorts and a shirt with a skull and The Grateful Dead printed across its back came into view and greeted the woman. Then Mrs. Yombo appeared in her orange and black lapa and white brassiere.

Robert allowed his eyelids to close and his face relaxed and his head drooped; he began sliding; deliciously, irresistibly. He heard voices and his head jerked up. He saw the iron bars, the two dugouts, the woman with the basket on her head, and Mrs. Yombo and the young man, still talking. And then the priest came from the kitchen with a bottle of alcohol, some steel wool, and a wad of cotton.

When Robert finished cleaning the connections the priest went outside and started the generator. Robert turned the radio on. Nothing. He worked his way through the set, checking one connection after another. Finally, he pushed back, looked up at the priest. “There’s nothing obvious—without a meter or the manual or a spare board—” He shrugged.

“We’ll know soon enough, anyway. All we have to do is wait and we will hear.”

Afternoon heat woke him. His body was slick with sweat. He rolled out of bed and limped across the hall to the bathroom, washed, changed into the khaki shirt and shorts the priest had laid out for him, then went to the living room—a long whitewashed, stucco-walled space. Gauzy white curtains were drawn back from the windows. The room was sparely furnished: a long rough-hewn table with a half-dozen chairs, side tables with lanterns and candles, and on every wall shelves of books. The floor was a checkerboard of black and beige tiles. A golf bag with a half-dozen clubs leaned against the kitchen door. Bits of moist grass clung to the club heads. The priest was at his desk, writing, the back of his khaki shirt dark and damp. Smoke from his cigarette rose from the ashtray and drifted out the window. He heard Robert and turned.

“You slept long,” he said, rising and going to the table. He pulled a chair out. “Come and sit.”

“Any word of the others?”

“Alusine and I went upriver, to the mound. Some farmers saw us and came and told us soldiers had come and found bodies in the river. Two soldiers and an old man with a blue shirt and trousers.”

“Pa Bangura.”

“Your driver?”

“Yes—what about the others?”

“Nothing.”

“I’m gonna take the canoe upriver.”

“We looked for them. Very thoroughly. We went as far as your lorry and we found no trace.”

Robert looked out the window at the dugout, still on the landing beach where he had pulled it up early that morning.

“The soldiers—” Robert said, his eyes still on the dugout.

“I didn’t see any.”

“If I went up as far as the doublecab—”

“It’s no use. We searched thoroughly.”

Robert looked at the priest. “Down river then? Anybody looked there?”

“No. It is possible they got out of the river.”

Robert thought of Prince lying semiconscious in the bed of the doublecab, and his last sight of Daniel, clinging to the side of the vehicle as it slid off the barge into the river.

“How is your foot?”

“Sore as hell.”

“I want to look at it.”

The priest got his scissors and cut the bandage off. He wrinkled his nose, held the bandage up to Robert. Robert shook his head; he already knew the smell.

“It seems worse. We’ll increase the sulfadiazine. Stand and loosen your trousers and let me look at your lymph nodes.”

Robert stood and pushed his shorts down to his knees. The priest ran his fingers down the crease of skin between Robert’s torso and thigh. He stopped when he felt bumps.

“Sore?”

Robert nodded.

The priest motioned for him to pull his shorts up, got to his feet and went into the kitchen, then reappeared a minute later. “Mrs. Yombo is preparing a potassium permanganate soak. And Alusine is making you a crutch.”

Robert told the priest then that he had decided to make his way by canoe to Bonthe. He would look for Daniel and Prince on his way down river. The priest looked surprised.

“My friend, you cannot make that journey in a canoe—not with that foot. You do not know—”

“I’ve traveled the lake and I’ve worked for years with the villagers in the Kitammi, below Gbap.”

“But the swamp.”

“There’s only a few miles of it—after that there’s Gbap. When I get there the fishermen will take me to Bonthe. I can contact Freetown from there.”

The priest shook his head. “You have no papers. If you run into soldiers—”

“There are no soldiers down there.”

“Your foot—”

“I’m going and you ought to go with me.”

The priest’s eyebrows arched. “Me? Go into that swamp?”

“The civil war started right here. This is where it will start again.”

“The soldiers will not harm me.”

“If there is fighting they’ll kill whoever seems to oppose them. They’re all terrified of white mercenaries.”

“We still don’t even know what’s happened.”

“We know enough. I think you ought to go with me.”

“No. I need to be here.”

Robert rested the paddle across the dugout in front of him and opened one of the plastic bottles of water the priest had put in the canoe. To his right he saw trees in the haze, to his left the white sky merging seamlessly with the silvery lake. His arms and shoulders ached and his shirt and shorts showed lines of dried sweat. His lower back had begun cramping again and his legs were numb. He took one more drink from the bottle and leaned back against the stern and closed his eyes and tried to relax the soreness and the cramps away.

He had pushed himself very hard to get as far as possible down the lake before the onshore wind came up, knowing that it would come right in his face and the work would be twice as hard. But the morning had remained calm, the lake flat, the silence interrupted only by the splash of his paddle. As he’d slid along over miles of river and then lake, and the long morning became afternoon, he had looked for Daniel and Prince, with little hope of finding them; and wondered about how things were in Freetown, wondered if there was fighting, wondered if Gunter and Rex and Alexander had been taken.

He felt his strength trickle back, thought about the tire patch kit, and wished he had some of the fine Kabala jamba. He pulled himself back to a sitting position and drank more water, then reached forward and got a piece of bread and a tin of sardines out of his knapsack. He opened the sardines and made a sandwich, and with the oil dripping on his legs, ate it, swigging water to get it down.

He guessed he was near the head of the river, but he did not know how it came out of the lake—whether through many small channels in the mangroves, or less ambiguously in a single wide channel that he could easily identify. There was no map of the area, but he did not need one; he had only to keep the shoreline on his right and he would come to the head of the river.

He finished his sandwich, swallowed some more sulfadiazine, and drank more of the water. He resumed paddling, at a leisurely pace, in no hurry now that he had traveled much of the distance he had hoped to make on this day. When he found the river the going would be easier.

He moved steadily along the meandering shoreline, entering every little embayment that opened up in front of him, following each to its termination at a wall of mangroves, expecting to find in each the head of the river. Not finding it, he would paddle on around the end of the bay and out into the lake again. Coming out of one such embayment he saw a shadow out in the lake and stopped paddling. It was a patch of gray against the white. As the patch moved slowly along it took on the shape of a man in a canoe. He paddled toward it. After a few minutes he saw that it had stopped. By then he was close enough to make out the profile of a fisherman bending forward. Robert shouted a greeting. The head came up, turned in his direction, and in turning revealed a woman’s profile. He waved the paddle. The woman watched him approach. In front of her in the canoe were several cylindrical fish traps and a basket of small fish. When she saw that he was a white man, she began paddling toward him.

He greeted her in Krio, telling her he was traveling to Gbap. He asked her where he could find the head of the river.

She responded in Sherbro, speaking too rapidly for him to understand. He interrupted, asking her to speak slowly. Pointing across the lake, she told him the river flowed out of the lake close to the beach near her village, which was called Bengani. She had heard from fisherwomen in a village one day’s travel up the lake that white men had come to help the people. She asked if he was one of them.

He told her that he was one of the white men, that he had gotten separated from his friends and was traveling by canoe to Bonthe. He asked her if she would take him to the river.

She said it was too late, she would bring him to her village, and the next morning she would show him the way.

The thatch roofs of the houses of Bengani were old and gray and smelled of rot. Mud had dissolved out of the walls of most, revealing sections of wattle skeleton. Under a cotton tree not far from the lake shore the villagers had built a baffa. Beyond that was the bushpole framework of a smoke-blackened banda. Over it all hung the smoky, acrid smell of dried fish, which even a strong onshore breeze did not dispel.

An old woman, a pair of old men, and many children came to the landing beach when they saw that one of the canoes carried a white man. One of the old men waded into the mud and pulled the bow of Robert’s canoe up on the grass. Robert steadied himself with his crutch, stepped gingerly out of the dugout. The children crowded round him, laughing and screaming.

The evening breeze kept the mosquitoes down. The flies were more troublesome: when the wind dropped even a little they came up from the ground in thousands. Robert put on the socks, long pants, and long sleeve shirt that the priest had packed into the knapsack.

He sat with several young fishermen and the two old men who had met his canoe in the afternoon. The smell of fish—dried and fresh—permeated everything, mingling with the smoke and the pungent sour sweat odor of the men who sat close around him in the baffa. Dusty potbellied children lingered outside the baffa, staring at Robert as they had all afternoon, intently and endlessly, not quite able to fathom his whiteness. On the earthen floor of the baffa an empty two-gallon antifreeze container rested on its side. It had recently contained palm wine. They had drunk it all. A cooking fire smoldered nearby, flaring up from time to time as an eddy of air pushed through the stones surrounding it.

The fishermen had heard from their cousins up the lake that white men had come and asked many questions about the problems of fishermen and farmers. They were very happy to see him, for they also had many problems. With only the barest preamble of courtesy they set about telling Robert their needs. They wanted guns to kill the animals that swam in the lake and tore the women’s traps apart. They wanted the white men to force the big shrimp trawlers from Ivory Coast to go far offshore where they belonged, and stop destroying the long lines. They wanted better fishing gear and more of it. They wanted the white men to come and help them get fresh water to drink, for they had to drink the brackish lake water, even though it made them sick. They wanted medicine for malaria and cholera and worms and polio and the other diseases that killed their children. They complained about the high cost of palm oil, which they could seldom buy nowadays, though everyone knew that without palm oil even the best upland rice and the biggest fish were poor food. And, of course there was the transport problem. Always, everlastingly, transport: the problem of all problems.

Robert tried to explain that he and his colleagues had come to learn about the problems so that they could help the villagers help themselves, but his command of Sherbro was inadequate. The young fishermen could not believe they heard him right because his words made no sense. After he spoke they looked at one another in puzzlement, then talked all at once. After a while Robert gave up explaining; he simply let them believe what they wanted to believe.

In late afternoon the girl who had led him to the village returned with her fish traps and her catch. As the fishermen talked about all the things they wanted he had watched her move about the smoking banda arranging her fish on the drying frame. Her eyes came up from her work often to see if he still looked at her. A little later he observed her at the cooking fire as she worked with the other women. Still later he watched her as she moved about the baffa, serving food and pouring the brackish water for the men. The upright springiness of her breasts and the small, hard muscularity of her belly and the bones showing beneath the skin of her back reminded him of Aminata.

Before the light was gone the women brought rice on a piece of flat metal that was shaped like a tray, over which they’d poured grin-grin plasas, which, though it had only a flavoring of palm oil, contained big pieces of fish. Robert ate like the others, with the fingers of one hand while he waved flies off the food with the other. To make up for the poverty of palm oil the women had made the plasas peppery hot. This made him thirsty, but he did not drink their water, and he did not drink his own, for he knew if he brought it out simple courtesy would require that he pass it around. Then it would be gone and he would have nothing but swamp water for the next day. They resolved the problem for him by topping some coconuts and then by bringing out the big yellow antifreeze jug full of palm wine.

Later Mister Sama, the headman, took him to one of the huts, which a young family had given up so that Robert could have it to himself. He got a candle from his knapsack and in its light he and Mister Sama tied his mosquito net to bushpole rafters so that the netting formed a tent above the dirt floor. Mister Sama ostentatiously admired the netting, hinting that he would love to have a thing like this—he would like it more than a gun, he said. Robert ignored the hints. When they finished Robert spread his sleeping mat and sheet under the netting and waited for Mister Sama to leave. But the headman lingered. Finally he spoke of the girl, saying she was strong and good to look at. Robert told him he was tired, and had to sleep now.

He rolled over and saw, a foot from his face, a spider as big as his hand, clinging to the mosquito net. He reached over the girl and fumbled about in the knapsack for the priest’s flashlight. Turning it on the spider, he saw that the creature was on the outside of the net. He slapped it with the flashlight. It bounced across the dirt floor toward the door-less doorway, recovered and darted off into a dark corner.

He sat up. The girl was curled on her side next to him with the sheet pulled round her. Scores of tiny braids trailed across her face. She stirred, murmuring something low and musical. He had been so full of codeine and exhaustion the night before he’d not discovered Mister Sama had sent her to him until sometime in the early morning when discomfort had brought him momentarily awake.

He rolled out from under the net, wincing from the pain that darted up his left leg, pushed himself to his feet and pulled his shorts up, then got his crutch and slipped his feet into his halfbacks and hobbled out of the hut. Wisps of fog hung in the air over the lake, little streamers of shadowy gray against the gray of first light.

His arms and shoulders were sore, his hands stiff, but these small discomforts did not diminish him; quite the contrary; he felt strong, rested. Perhaps the sulfadiazine was working. He went back inside, got a handful of the yellow tablets from his knapsack, which he swallowed with water, and then got some toilet paper and limped in the half light past several huts, working his way along a trail through grass along the shoreline, until he came to a brushy place where the sweet, rotten smell of old shit hung in the air. Mister Sama had told him where he would find this place. He found a clear spot, stepped out of his shorts, squatted.

When he came back he took the cooking pan from the knapsack and got some water from the lake and returned to the hut. The girl was sitting cross-legged in the tent of mosquito netting, with the sheet pulled round her shoulders, yawning. Through the netting she watched him wash, her dark eyes roaming frankly over his chest and crotch and legs, studying him like the children had studied him, with open-mouthed intensity, as if seeking to understand the disfiguring whiteness of him—particularly that pallid band of sickly translucence around his torso from his belly down to his thighs.

When he was through washing he went to his knees and slipped under the netting. The scent of soap lingered in his nostrils. Against that freshness she smelled strongly of dried sweat. She looked up at him through strings of plaited hair, her eyes big, her lips full. But for breasts and the patch of black hair between her legs, she could have been taken for a child. He knelt before her, to get his knapsack, and she, thinking he was readying himself for her, stretched herself out and opened her legs to him. She looked intently up at his face, her white teeth peeking out from behind big outward thrusting lips, her face the fat-tight face of a child.

He got the knapsack, stood, got into his shorts, began taking down the mosquito netting.

He followed her canoe through tendrils of fog that hung vertically above the silvery lake. She stopped paddling and he glided up to the side of her canoe, reached across the water and grasped the side of it and brought the two dugouts together. The canoes rocked gently, turning slowly.

She pointed. Two hundred yards away walls of mangroves receded into the haze. He looked back at her. She knelt in the canoe, her weight back on her heels, her lapa round her waist, her upper torso bare. Piled in front of her in the canoe were a half-dozen fish traps—light, graceful, fragile cylinders of reed and grass.

He opened one of the side pockets of his knapsack, which the priest had stuffed full of two-leone notes, and pulled some of the money out, passing the bills over the water to her. Her eyes lit up and she smiled and bobbed her head and murmured her thanks. He said good-bye and pushed off, paddling toward the gray void that opened between the mangrove walls. After a few minutes he glanced over his shoulder. All he saw was the silvery lake merging into dimensionless white sky.

It was as Mister Sama and the others had said. The water moved, but very slowly, almost too slowly to notice. They had said the river was really part of the lake, except that it moved through many narrow, meandering channels that came together every few miles in a body of almost still water, which would be perhaps a mile long and a quarter mile wide, then the water would flow back into narrow channels. They had warned him to be careful about the side channels, to stay always in the biggest stream, so that he did not lose his way. If he came to a place where he was not certain of which channel to take he was to put a leaf in each of the channels and take the channel in which the water moved. He must proceed carefully and patiently. If he did not make it through to the Sewa on the first day, he should find a place where the channel meandered close to the storm berm that separated the ocean from the mangrove swamp. There were sandy places where the mangroves were thin, and he should beach his canoe at one of these, go up on the storm berm, and sleep on the ocean side to get away from the mosquitoes.

It seemed clear enough when they talked about it, but it was confusing in reality. Most of the time he was uncertain if he was in the river or in some side channel. The swamp was a place of black mud, still water, and motionless heavy air; of luminous greenish light and no sun; of rank shoots and runners that wove themselves together in a warp so impenetrable that even the light was dimmed by its roof of thick greenery, through which he saw not even a glimmer of the white sky.

He lost his way in the hottest part of the afternoon. His movement over the water had awakened the mosquitoes and his sweat kept washing the repellent off his legs and arms and face; his whole body tingled and itched maddeningly from the hundreds of bites. In his growing impatience he paddled the canoe more swiftly. When he came to a place where the channel split into two waterways, he chose too quickly and a half hour later found himself in a dead end of mud and tangled runners, a mile from the main channel. He could not even turn the canoe around. He had to turn himself around in the canoe—a difficult, painful maneuver—before he could paddle it back to the main channel. He came to one of the meanders the villagers had told him about, recognizing it only because he saw light through the mangrove wall. He paddled the canoe up to the place where he saw the light and grasped one of the runners and pulled the canoe up against the mud shelf. He reached up and grasped a runner, raised himself to his feet, looked into the tangle, and saw a patch of dead grass beyond the black mud.

He lowered himself back into the dugout and got the tape from the first aid kit, slipped his bandaged foot into the sandal and, setting his jaw against the pain, ran a band of tape under his heel and around his ankle over the bandage. He taped the other sandal on his right foot and grasped the runner above his head and raised himself to his feet once again, slipped his arms through the straps of the knapsack and settled it on his back, then stepped out of the canoe, reaching behind him as he did so and pulling it on to the mud.

It took much effort to work the bow of the dugout into a break in the mangrove wall. He was sweating heavily when he got his crutch and began working his way into the web of shoots and runners, which kept grabbing him, slowing him.

The mangroves petered out over a hundred yards, the last fifty yards of which he negotiated without sinking more than ankle deep in the black mud. By then pain enveloped his entire leg. The sandy, brushy face of the berm rose to a height of twenty feet. He limped slowly up the slope through patches of brittle gray grass. At the top he found low dunes, grass, and scattered palm trees, and he heard the rumble of surf. He looked back over the swamp, which extended in an unbroken green carpet that became greenish gray, then dark gray, then a light shade of gray against the white sky. There was no feature that he could memorize and come back to. It was all the same and it looked like it went on forever. He gouged at the sandy soil with his crutch until he had disturbed it enough to see it from a distance, then hobbled off toward the ocean. He came to a shallow depression that ran along the length of the berm and parallel to the beach on the other side. He limped down into the depression and crossed it, climbed up the other side and passed through dead grass and another stand of palms, stopping from time to time to dig at the ground with his crutch until he had made a mark he could easily find. He crossed two more depressions before he came to the ocean.

By then he was moving against the pain more than the terrain. Moving toward the sea to wash his feet clean of the fetid black mud and himself clean of the sweat. And wash himself clean of the pain with the codeine, but that only when he had reached the ocean and washed the sweat and mud away; only then would he allow himself to swallow the codeine, for the pain would not stop even with the codeine if he was moving about. He focused on the things he had to do: getting through the pain to the sea; washing in the salt water; resting. And of course the codeine; and on eating—though the pain had driven hunger out, he knew he had to eat—and on making a place to sleep; and then, when he had something in his belly, swallowing more of the priest’s sulfadiazine.

He dropped the knapsack at the top of a steep face of coarse yellow sand, his presence sending hundreds of crabs skittering down into the surf. He sat in the sand, got his knife out of the knapsack, and with shaking hands cut the tape away from his halfbacks and slipped them off. After cutting away the blackened bandage he pushed himself to his feet and limped down the beach face to the water’s edge, stripped off his clothes, and stepped into water as warm as a bath. The sandy bottom was steep; in three or four steps he was up to his chest in the warm water. He pushed off, dove, rose and swam out into the ocean. He turned. Amazingly, the beach was moving, perceptibly moving. The water was transporting him toward the northwest, in the direction he had traveled all day: a strong longshore current moving him as fast as he could swim. He laughed, delighting in the absurdity of the ocean moving so much faster than its daughter, the river; thinking he could forget about the river and the swamp and that fucking ass-numbing back-cramping dugout, he could turn on his back and rest and stare at the white sky while the ocean carried him to Sherbro Strait. Then he sobered, realized that he was no longer twenty feet off the beach, he was fifty yards from the beach. He panicked, threw himself toward the band of yellow sand, kicking and stroking, flailing at the water with an energy that he did not know was still in him. It took all of that energy, every ounce of it, to get the sand beneath him again. He stood, waist deep, his chest heaving, his legs quivering, his arms hanging like logs, the water tugging at him like a mountain stream. Shivering with the chill of water evaporating into the dry air, and from exhaustion, he pulled himself up on the beach, scattering crabs. As he limped back toward his clothing, some 200 yards away, he came upon sea-whitened nubs sticking out of the sand, the only feature breaking the smooth yellow coarseness of the steep beach face for as far as he could see. He stopped. One of the white nubs rose high enough out of the sand for him to see that it was a bone, a curve of white that could have been a rib. He knelt to look more closely, saw among the nubs of bone a fragment of cloth. He pushed himself to his feet, backed away from the remains of some fisherman, a cousin perhaps of the young woman with whom he had lain the night before. He looked down at the nubs of bone for a long time, then turned and limped along the water’s edge toward the pile of his clothing, which the crabs swarmed over and picked at, looking for the rotten stuff of which the clothing smelled. Beyond the clothing, going off into the distance, the surf haze hung above the steep face of the beach, mingling with the Harmattan haze, and beneath the haze, as far as he could see, thousands of crabs scurried in and out of the surf. He limped along, ankle deep in water, scattering the crabs before him, welcoming the chill that came as the water evaporated from his skin. He rinsed his sweat-wet clothes while the surf broke and rolled around him, then climbed the face of the beach. He opened his bedroll and spread his blanket and sat on it, then opened the knapsack and got one of the water bottles.

He brushed sand off his swollen foot and with a shaking hand poured water over the wound. He let the air dry it, then got the antiseptic salve and smeared it over the exposed flesh. Only then did he let himself swallow some of the codeine. He bandaged his foot and stretched out on the blanket and closed his eyes, remembered then that he had eaten nothing but the coconut jelly the girl had offered him that morning. He sat up and opened the knapsack and got the dried fish that she had wrapped in a banana leaf. He bit off pieces of the fish and looked up at the silver disk of sun, which was falling through the white sky toward the sea. It would turn to yellow soon and then it would redden and disappear.

The fish was the best that the villagers had to give: big pieces of kuta, brown from the smoke on the outside and white and firm inside. Not at all like the herring and the bonga shad that was the upland staple—small, desiccated, leathery, smoke-blackened, and not much bigger than a hand; caught in thousands in the ringnets of Ghana boats and dried by thousands over smoky fire—guts, skin, head, and all—with a taste of smoke and rancid fish fat even when fresh off the banda. No, the fish in his hand was solid and tasted good even without palm oil. He raised the piece of fish to his mouth—and saw that the white, shiny flesh moved. Astonished, he looked more closely. Oh God! Maggots! Scores of glistening white things swimming in the white flesh of the fish. His stomach knotted, quivered, jerked. He pitched the fish down the face of the beach, scattering crabs, put his face to the sand and vomited.