The Academic Index (AI)

In this chapter, I will reveal one of the central mysteries of the Ivy League admissions process, the academic index, or AI.* No matter how many books you have read on admissions, you will not see a reference to this index, because it has always been a kind of trade secret. I am now using the term Ivy League intentionally—although you can apply this formula to all highly selective colleges, the formula itself is used solely at the eight Ivy League schools. The AI is a formula that combines the averages of student test scores (both SAT Is and SAT IIs) and high school rank in class (represented by an Ivy League invention, the converted rank score, or CRS). The Al is represented on a scale of 1 to 240, with 240 being the highest. In order to have a sense of the AI scale, please bear in mind as you read this chapter that the average applicant to Dartmouth typically has an Al of around 200, while the average AI of the matriculating class is about 211.

Most of the highly selective colleges use two ratings for each student, an academic ranking and an extracurricular/personal rating. Each officer assigns a ranking to every student and that ranking is represented as a fraction, academic over extracurricular/personal. For example, if a school had a 1 to 9 scale, with 9 representing the highest rating, a student could receive any combination from a 1/1 to a 9/9. Using this 1 to 9 scale, a 5 would be the average applicant in the Ivy pool.

Let's take a look at how this ranking system is used. For example, a student may be ranked as a 9/6. This would mean that the student is in the highest-possible academic category (probably at the very top of his class, with very high test scores and lots of academic power) and has an above-average to excellent involvement and leadership in extracurricular activities. In contrast, a student with a rating of 3/4 would be a below-average candidate academically for the Ivy League. The numbers show decent extracurricular involvement, but probably the student occupied few leadership positions. The 9/6 would be a certain admit, while the 3/4 would probably fall short of admission.

Selective colleges give much more weight to the academic ranking than to the extracurricular/personal rating—typically, between 70 to 85 percent of the final decision will be based entirely on the academic ranking. This academic ranking is directly proportional to high school achievement and standardized testing scores. High school achievement in the Ivies can be measured by the CRS, which is integral to calculating the AI. The CRS tries to establish a uniform method for comparing high school rank or standing for all students applying to college. In most of the Ivies, the AI is directly proportional to the student's academic rating, even if the school does not base its ranking strictly on the AI calculation.

Before we delve into the intricacies of the AI and CRS calculations, it will be helpful to define a few key terms and concepts. The most important is the concept of weighting, which can be applied either to rank or GPA. Basically, if a high school weights grades, it adds a certain point value to advanced courses such as honors or AP classes. There are many different ways to weight grades, but one typical one is to add .5 points to the final grade achieved in an AP class, so if the student earned a 4.0, he would receive a grade of 4.5 for that class. If grades are reported on a 1 to 100 scale, sometimes two to three points are added for advanced courses, so a 94 would be weighted to a 97. Since every school has a different system, it is impossible to give a range of GPAs—unweighted grades tend to be reported on a straight 4.0 or 100-point scale, while weighted grades can be reported on a scale that goes up to 4.5 or higher or over 100 in a 100-point system.

For high schools that weight the final rank, usually the grades on the transcript are reported exactly as they are (in an unweighted form), but honors or AP classes are taken into account when class rank is computed. In these high schools, if two students had a 4.0 but one student took more APs than another, that student would be ranked correspondingly higher in the final class standing.

For Ivy League purposes, the most helpful way of reporting grades is really a weighted rank, which tells the colleges how hard your courses are and how you have done in relation to the rest of your class—both at the same time. The next best thing would be unweighted class rank, since colleges can see how your grades compare to your classmates’ and they can use the school profile or the guidance counselor's explanation to figure out how hard your course load has been. GPAs by themselves are not very helpful if the college cannot calculate roughly where that GM would put you in relation to your classmates. With these basics in mind, let's turn to the subject at hand, the AI.

Knowing your academic index, along with having a complete understanding of how applicants are evaluated, will give you a good idea of what your chances are for gaining admission to an Ivy League or highly selective college. One crucial fact before we begin: You must learn how the AI is used before you can fully understand how it can help you estimate your chances of being admitted to an Ivy League school. With this understanding in mind, I have organized this chapter into five parts: calculating the AI; inequities and other problems with the AI; how to override the AI to make it more equitable; academic ranking systems; and what you might be able to do about improving your chances for admission.

CALCULATING THE AI

As I'sve already mentioned, the AI is the sum of three factors: (1) the average of your highest SAT I math and verbal scores, each rounded to two places (800 and 800 would be 80 + 80 = 160, not 1,600); (2) the average of your three highest SAT II subject tests (also rounded to two places, so that 750 = 75, 640 = 64, 500 = 50, etc); and (3) your converted rank score (CRS). In 1996, the formula was changed slightly, but since the change was not very dramatic and only intended for recruited athletes, I will not elaborate here. These factors are set forth in the AI Blue Book, which is used by all Ivy League admissions officers, or at least by the systems technicians, who are the ones who actually do the math and then input the results into the computer for the officers to see. Here is my rendition of the formula used for calculating the AI:

Again, note that the average test scores are rounded to two places so that an 800 becomes 80, and so on. In addition, the highest scores are used, so if a student took the SAT I three times, only the single-highest verbal score and the single-highest math score would be used for the calculation.* Since the highest-possible CRS is 80, the highest-possible AI is 240. Thus, if a student scored double 800 on the SAT I, 800 on all three SAT II subject tests, and was valedictorian in a class of 350 students, that person would have a perfect AI of 240.* Of course, this is extremely rare, but it gives you an idea of the very top end of the academic scale.

Let's look at another basic example. Suppose a student has a CRS of 67 (next, we will look at how the CRS is calculated), SAT I scores of 700V, 800M, and SAT Its of 600, 650, and 700. The average of the SAT I scores is 750, but we have to round it to two places—hence, 75. The average of the SAT Its is 650; rounded to two places, it is 65. And the CRS is 67. Therefore, in this case, the AI is 75 + 65 + 67 = 207.

The first two components of the AI—the average of the highest verbal and highest math SAT I and the average of the highest three SAT II scores—are very easy to calculate. Let's focus on the third component, the converted rank score, or CRS, since this is much harder to calculate. As the name suggests, the purpose of the CRS is to transform class ranks generated in a variety of different ways, from a variety of different high schools, into one uniform scale. This common scale facilitates comparisons between students graduating from different high schools. Eighty represents the highest-possible CRS score.

Earlier in this chapter, I explained weighted grades and weighted ranks. There is an established order of preference for determining CRS in the Ivy League. This means that the systems technicians in every Ivy League office calculate the CRS by first looking for exactly how each school reports rank. They are bound by Ivy League regulations to use the following order of preference:

1. Exact rank (weighted if available; if not, unweighted)

2. Decile, quintile, quartile rank

3. Weighted grade point average (as provided by the high school)

4. Unweighted grade point average (as provided by the high school)

5. Unweighted grade point average (as calculated by the systems technicians in each Ivy League office)

This means that if a high school reports both an exact rank and a weighted grade point average, the Ivies would be bound to use only the rank, since that factor has a higher preference. If a high school reports both weighted and unweighted rank, the Ivies are bound to use the weighted rank. Here is how your CRS is computed for each of these different scenarios.

CASE 1: RANK

The first component the systems technician looks for is your class rank. Your class rank is either weighted or unweighted, if your high school ranks at all. A weighted class rank adjusts your class rank for the degree of difficulty of your course load. For example, suppose you took very demanding AP courses during your junior year and your high school employed a weighted ranking procedure. If, after adjusting your grades in these courses, you ranked sixth in a class of 120 seniors, your weighted rank will be reported as 6/120. If your high school does not adjust your grades for their degree of difficulty, it is using an unweighted ranking procedure. As I have explained, the Ivy admissions officers are obliged to use the weighted class rank, if this is reported.

To find your CRS, first ask your guidance counselor where you are ranked as of your senior fall, when you will be applying to colleges (or as of junior spring, in order to get a rough idea); then look in the appendix at Table A for the number of people in your senior class. Again, let's suppose that you are ranked sixth in a class of 120 and that your high school reports only the unweighted rank.*

There are two ways to figure out your CRS from an exact rank. The quickest and easiest for an individual (as opposed to a computer) is to use Table A. Find the section of the table that reflects the size of your class, go down the left-hand column to find your rank, and then look at the right-hand column to find your CRS. If you look under the heading “Class Size 100–149” and then look for number 6 in the left-hand column, you will see that the CRS in the right-hand column is 67. The way the computer calculates your CRS yields the same result. It is worth running through one example so you can assure yourself that both methods yield the same result.

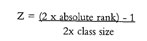

The computer uses the following simple formula:

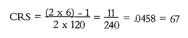

After the computer calculates this decimal (Z), it then locates the resulting number in Table B in the appendix to ascertain the CRS. In the case above, we would use 6/120 as the rank and apply it to the formula as follows:

Note that once you compute the decimal value, when you look at column “Z” in the table, you always pick the next-highest decimal, which corresponds to the lower CRS. In the case above, the student would get 67 out of a possible 80 CRS points no matter which method was used to compute the CRS.

CASE 2: PERCENTILE RANKINGS

What if your high school does not provide a weighted or an unweighted rank? In that case, things get more complicated, and the next option is used. Let's take a new example and say your high school reports a decile ranking, such as “within the top 10 percent,” or a quartile ranking, such as “within the top 25 percent.”*

How do the Ivies determine class rank when only percentage information is provided? The short answer is that the AI Blue Book tries to define as precisely as possible what the phrase “top 10 percent” means and then multiplies the appropriate percentage by the size of the class to obtain a “best guess” of what the true class rank might be. In other words, since colleges cannot tell if you are at the very top of the top 10 percent of students (let's say number one out of a class of one hundred students) or at the very bottom of the top 10 percent (number ten out of one hundred students), they try to be fair by putting you in the middle of the distribution, which in this case would be number five out of one hundred students, even though that is clearly an approximation of “top 10 percent” and not an exact rank.

The language of the AI Blue Book is about as clear as the tax code, but here is the technical description of what the Ivy officers must do in order to arrive at your CRS. First, the reported top decile, quintile, or quartile is translated into a percentile. Next, the midpoint of that percentile must be found. The resulting percentile is then subtracted from 100 and the result is divided by 100 to yield a percentage. In formula form: 100 - ×% ÷ 100 = %. The resulting percentage is multiplied by the number of students in the graduating class to obtain an imputed class rank. The imputed class rank is used in conjunction with Table A to obtain the CRS.

Describing the process might make it sound more complicated than it actually is. Let's look at the following example in order to clarify the sequence. A person who graduates within the top 10 percent of the class could have graduated in the top 1 percent (so he would be better than 99 percent of the students) or ahead of all but 10 percent of his classmates (in which case he would have been better than 90 percent of the students). A statement that the student graduated “within the top 10 percent” is not specific enough to locate precisely where within the distribution of class performance a student lies. Unless the exact position in the distribution is indicated, the members of the Ivies have agreed that the midpoint of the relevant distribution is used—in the example above, the midpoint would be number five out of one hundred students, since that represents the midpoint between number ten and number one of one hundred students. Consulting Table A, you can see that the resulting CRS would be 68.

So for purposes of the formula, a student who graduated in the first quartile, or top 25 percent of the class, did better than 87.5 percent of his classmates, 87.5 percent being the midpoint between 100 percent and 75 percent. Let's say that the student's graduating class had 445 students. The student's imputed class rank is 56/445. This is found by subtracting 87.5 from 100, dividing the result by 100—yielding .125—and multiplying .125 by 445 (56). By consulting Table A, you find that 56/445 equals a CRS of 61. Demonstrate to yourself that someone in the second decile in a class of 153 would be determined to have a rank of 23/153, or a CRS of 62.*

CASE 3: NO RANKING AND NO PERCENTILE INFORMATION PROVIDED

When your high school does not provide rank or percentile information the Ivy League AI Blue Book suggests that officers do everything possible to force a rank using the high school profile.* If it is impossible to tell from the high school profile and the high school will not help, the general conversion table must be used (see Table C in the appendix).

It is quite possible that you attend a high school where rank and percentile information is not provided. Surprisingly, the computation of your CRS in this last case is quite simple. Table C converts your GPA or letter grade directly into a converted rank score.

On a final note, the AI Blue Book has a separate section of tables from several high schools with unconventional grading systems, sometimes on a 1 to 12 scale, or a 1 to 6 scale—there is quite a range. These high schools either have their own special CRS tables that systems technicians in each Ivy office must refer to when calculating CRS or they use methods that are not specific enough for determining rank, so the Ivies simply recompute a GPA or perhaps have directions to use either the weighted or unweighted GPA—it is different for every school. Some of the high schools in this special category are: Brearley School (New York, NY), Brooks School (North Andover, MA), Burke Mountain Academy (East Burke, VT), Choate Rosemary Hall (Wallingford, CT), Collegiate School (New York, NY), Darien HS (Darien, CT), Fairfax County Public Schools (Virginia), Friends Academy (Locust Valley, NY), Gilman School (Baltimore, MD), Greenwich High Schools (Greenwich, CT), Groton School (Groton, MA), Gunnery (Washington, CT), Head Royce School (Oakland, CA), Hillsborough HS (Tampa, FL), Holmdel HS (Holmdel, NJ), Hopkins Grammar Day Prospect Hill School (New Haven, CT), Horace Mann School (New York, NY), Hotchkiss School (Lakeville, CT), Kent School (Kent, CT), Lakeside School (Seattle, WA), Lexington HS (Lexington, MA), Longmeadow HS (Longmeadow, MA), Milton Academy (Milton, MA), Montgomery County Public Schools (Maryland), Newton North HS (Newton, MA), Phillips Academy (Andover, MA), Phillips Exeter Academy (Exeter, NH), Pingry School (Hillside, NJ), Princeton Day School (Princeton, NJ), Princeton HS (Princeton, NJ), Ransom Everglades School (Miami, FL), Regis High School (New York, NY), St. Alban's School (Washington, DC), St. Ann's Episcopal (New York, NY), St. Mark's School (Dallas, TX), St. Paul's School (Concord, NH), St. Stephen's Episcopal (Austin, TX), Stratton Mountain Academy (Stratton Mountain, VT), Tabor Academy (Marion, MA), Taft School (Watertown, CT), Townsend Harris (Flushing, NY), Trinity School (New York, NY), United Nations International School (New York, NY), Western Reserve Academy (Hudson, Ohio), Wheeler School (Providence, RI), and the Wooster School (Danbury, CT).

If you attend one of these high schools, you can still use the methods I have outlined in this chapter, because they will yield very similar results, but if you really want an exact number, see if your college counselor knows what the special table is for your high school or what method the Ivies use. If your counselor-does not know, just revert to the standard method for calculating CRS.

INEQUITIES

The factors in the AI formula are weighted equally. Thus, the first thing that should strike you is that two-thirds of this formula is derived from test scores, while only one-third is derived from a student's high school GPA or rank. This is in direct contrast to what all the Ivies say in their literature—that is, that the most weight is given to academic performance in high school, followed by test scores. As I have stressed in the preceding two chapters, test scores are very important. Now you can begin to see exactly why this is so.

Moreover, the CRS is not comparable in all cases (and therefore, neither is the AI, since the CRS is one of its three components). This is because it is calculated in different ways, depending upon the information provided by the high schools. As you have just seen, it can be calculated using methods ranging from exact rank (sometimes weighted, sometimes unweighted), to GPA (sometimes weighted, sometimes unweighted), to approximations derived from deciles, quartiles, or quintiles, to recomputed GPAs.

What are the inequities involved in calculating the CRS using exact rank? To answer this question, let's take a closer look at Table A and compare several number-one-ranked students. Consider the case of two valedictorians, one from a small graduating class and the other from a large one. One striking fact that you will notice is that if you come from a small high school, your CRS will automatically be on the low side. Thus, the number-one student in a class of twenty-four seniors can obtain a maximum CRS of only 70 out of a possible 80. If the second student was ranked at the top of a class of three hundred or more students, he would earn the highest-possible CRS: 80.

You might think that you'sd get additional credit if you graduated from a very large high school, but this is not the case; no additional credit is given if you graduate from a high school with more than three hundred students. You will earn the same CRS if you are number one in a class of three hundred students or number one in a class of two thousand, even though in the latter case the accomplishment is more impressive. Through no fault of your own, you will be handicapped in terms of the AI if you attend a small high school and your high school reports a rank rather than a GPA. In general, students in large high schools, whether public or private, fare better than those in small high schools if their school reports an exact class rank.

What are the inequities involved in calculating the CRS using decile, quartile, and quintile approximations? The first problem is that officers are using approximations. Because the midpoint only approximates the student's actual location in the distribution, high schools using percentile, quartile, or other relative ranking measures will inadvertently hurt their very best students, because the true rank of these students will generally be understated by the approximation. In other words, in the example we have used before of the number-one student in a class of one hundred students, numbers one through four will be hurt by the approximation, since it assumes that their rank is number five, the midpoint of the first decile. On the other hand, high schools that use these relative ranking measures will enhance the prospects of relatively weaker students, because the true rank of these students will be overstated by the approximation. In this same example, numbers six through ten would be helped, since their rank is “raised” to number five.

My own high school, with its typical senior class size of around 120 to 135 students, has inadvertently handicapped its top students since the school board abolished rank a few years ago. Now the school uses a decile system, so usually the highest CRS possible is around 67 of the full 76. Thus, the very top students from this school are starting out with a nine-point handicap, which, as you will soon see, can be the difference between a top academic ranking and a mediocre academic ranking. How is this decile rank computed?

As we see from Table A, the number-one student in a class of between 100 and 149 students would have a CRS of 76. But if only “first decile” is reported, even this top student can get only a maximum CRS of 67, since the midpoint of the first decile is used yielding an imputed rank of 6/120, or a CRS of 67 (Once again, the midpoint of the first decile is 95, subtracted from 100 is 5, and divided by 100 is .05. Multiplying .05 by the class size of 120 yields 6, so the imputed rank is 6/120 and Table A shows that the corresponding CRS is 67.)

Finally, what are the inequities in calculating the CRS using straight GPA? To answer this question, we need to examine Table C closely. A student with a 95 GPA* would get a whopping CRS of 77 out of a possible 80. But what if that student had only been ranked in the second decile if the high school had reported a decile rank? If the high school did not report that decile, the student would be awarded a CRS of 77, even though in this case the CRS would be tremendously inflated. In other words, it makes a big difference in this case if your high school reports GM rather than just a decile. The student in this example would receive a boosted CRS just because the high school reported a GPA instead of a decile ranking. Conversely, the student would receive a much lower CRS if the high school used decile ranking rather than GPA, even if he had a rather high GPA.

To make matters worse, the most striking thing about Table C is that it makes absolutely no allowance for weighted or unweighted CPAs. In other words, what if your high school only has a 4.0 scale and you have a perfect 4.0? Unfortunately, you could only get a CRS of 77 out of a possible 80, since the only way to get a 4.3 GPA and a CRS of 80 is to have a weighted average that would bring your CRS up to its full value.

In an even more pointed example, what if a student from. one high school has a weighted 93 average, while a student from another high school has an unweighted 93 average? (Assuming that they are taking the exact same number of AP classes) Common sense tells us that the student with the unweighted GPA really has a higher GPA (and deserves a higher CRS), since no credit has been given for honors or AP classes; but, according to the CRS formula, both students would get exactly the same CRS, 73 out of a possible 80. Finally, what if the rating scale goes up to a number higher than a 4.3 GPA? Let's say a student had a 4.4 weighted GPA, but that only represented a student in the second decile, because the highest weighted GPA at this high school was a 5.2. According to the table, any student with a GPA of 4.3 or above would get a CRS of 80, even if his average was nowhere near the top GPA at the high school.

HOW TO OVERRIDE THE CRS IN UNFAIR CASES

In practice, admissions officers do not blindly accept the CRS, since in many cases one ends up comparing apples to oranges. In many of the examples I gave in the previous section, an officer can override the CRS. Officers scrutinize the CRS, particularly in cases other than exact rank. If the CRS seems truly unfair, officers have the authority to raise or lower the CRS, and therefore the AI, accordingly.

How do admissions officers obtain their information so they can make fair adjustments? Even in the absence of rank and percentile information, many high schools provide detailed profiles of their classes to assist the admissions office. The profile might provide a histogram or bar graph so that it is possible to figure out where the student fits in the class.

Let's say the college counselor provided only a GPA—88 (B+)—since the high school had a no-rank policy. If the high school did not provide any kind of decile distribution, the admissions office has no way of knowing whether 88 represents a good GPA at that high school or a weak GM. Officers would probably assume that it was not a very high GPA if the college counselor did not provide more information. The situation would be entirely different if the college counselor provided a grade distribution that looked like this: A = 88-92 (4 percent of class), B = 83-87 (12 percent of class), and so on. Suddenly, the officer could tell fairly accurately where the student falls in the class, even though the high school does not rank—in this case, an 88 average is rather high (judging from this profile, grading is tough at this high school) and would put the student in the top 4 percent of the class. In a case like this, the officer would give the student additional CRS points and raise the AI accordingly because just the 88 GPA does not give accurate-enough information—by itself; it would drop the student's CRS to a 67.

How does a shared rank affect the overriding of the CRS? If an officer noted after reading the profile that forty students in the high school shared a number-one rank,* he would probably knock the CRS/AI down manually because there is no way to pinpoint if those students really were number one or number forty. Conversely, if a student had a “first decile”- based CRS that only converted to 67 but the college counselor said something like “We don't formally rank our seniors, but if we did, Maria would be number one because she has the highest GPA in the class,” the officer would boost the CRS several points (depending on class size), which would boost the AI.

In short, officers are always on the lookout for unfair use of the CRS. However, the less information the high school provides, the less the officer can exert influence to change the CRS. If there is no evidence one way or the other—just a GPA reported totally out of context—there is nothing the officer can do. In order to change the CRS manually, the officer must provide a quick written explanation so all who read the file can understand the rationale behind the decision.

There are some general rules I would like to provide for the benefit of college counselors regarding how best to report a student's class performance to highly selective colleges.

1. In high schools that have very small senior classes (under forty-five to fifty), the high school is better off reporting a weighted (or unweighted) GPA instead of a rank. As you can see from the CRS conversion tables, even if a student is number one but comes from a small high school that has only twenty seniors, that student's CRS will be quite low. The CRS is always abnormally low when using rank in a small class, even if the student is right near or at the top of the class.

2. In high schools that have large senior classes (over one hundred or so), it is much better to report an exact rank than to provide a decile, quartile, or quintile. If for some reason the high school board forbids reporting rank, the high school counselor can easily get around this prohibition by providing a grade breakdown: 94–99 (3 percent of class), 90–93 (4 percent of class), 85–89 (7 percent of class), and so on. In this case, a student with a 93 GPA would be roughly in the top 3 to 5 percent of the class. Notice that this approximation is much more accurate than just saying “top decile,” which only states that the student is between the top 1 and 10 percent of the class.

3. For small high schools that report only a GPA, it is crucial to provide some kind of written explanation as to where in the class that GPA puts the student. What happens if admissions officers have no information at all, just a reported GPA of 92? As I explained in a previous chapter, if officers have no way of figuring out where a student stands in the class, they almost have to ignore the student's entire high school record. Thus, they have to rely more on the student's own writing, standardized testing, and teacher recommendations. Testing will get a disproportionate amount of weight, which almost always hurts the student.

4. Finally, high schools should be consistent for all students, even if a few different guidance counselors write the school recommendations (as is the case with large senior classes where the class is split up among two to ten different counselors). Most officers keep notebooks, so if they know that a big public high school always uses rank, but for some reason the school reported three students in deciles but fifteen others with rank, they would have to call the high school to ask for the exact ranks of those three students. Schools should pick a system and then apply that system to all students, regardless of where they fall in the class.

ACADEMIC RANKING SYSTEMS

All the highly selective colleges use a ranking system of some kind for the academic criteria of every applicant, and usually the same ranking system for the extracurricular/personal criteria. As I have said, the final ranking is usually expressed as a fraction, with the academic ranking over the extracurricular/personal ranking. In this chapter, I am referring only to the academic ranking, but later we will consider the extracurricular/personal rating, as well.

In order to get an idea of how the ranking systems work, let's look at some representative examples from highly selective colleges. Harvard uses 1–6 for both rankings, with 1 being the highest; Brown uses 1–6 with 6 being the highest; Columbia uses 1–5; Cornell does not use a numerical ranking system—instead, they invite faculty to evaluate parts of the file; Amherst uses a 1–5 system, with 1 being the highest; both Dartmouth and the University of Pennsylvania use a 1–9 system, with 9 being the highest; Georgetown uses a 1–5 system, with 5 being the highest; Princeton uses a 1–5 system, with 1 being the highest (they also recompute a GPA for every applicant on a 4.0 scale that leaves out ninth grade); Yale uses a 1–4 scale, with 1 as the highest; and MIT rates 1–5 on both an academic and personal scale, using a system of cells such that one cell is 5/5, one is 5/4, one is 5/3, et cetera, for every possible combination. Stanford gives all its admissions officers a four to-five-hundred-page manual when they start work; it explains the many different areas in which they rate students. They seem to avoid numerical ratings for the most part and to rely on prose descriptions in many different categories.

I'll use Dartmouth's ranking system of 1–9 (9 being the highest) as a representative example that can be effectively applied to all the highly selective colleges, even though the scales are not identical. Before looking at the numerical determination, study the prose descriptions of the different academic ratings at Dartmouth. They will also give the reader an idea of the competitive nature of the applicant pool.

A 9 ranking. Academic 9s are the créme de la créme of the entire applicant pool. Typically, they represent the top 1 percent of the total number of applicants and their most salient quality is an intense love of learning. Love of learning and the pursuit of intellectual endeavors in school is characteristically coupled with academic initiative outside the classroom. Often, these students take college courses or follow up on their interests by means of special projects, research, and independent study involving extensive reading and writing. Students in this category explore a wide range of subjects, from astronomy and classical archaeology to zoology, impelled by their own curiosity. It is not unusual for academic 9s to be valedictorian or salutatorian of their high school and taking challenging honors/AP classes. The intensity of these intellectual pursuits suggests that academic 9s have the potential to become leaders in the academic/intellectual field of their choice in the world beyond college.

A 7 ranking. Academic 7s are among the strongest in the applicant pool as well, but they tend to show a little less evidence of the academic intensity and love of learning than do academic 9s. Even so, these students still show an impressive inner drive to achieve and, indeed, are perceived as high achievers by peers and educators. In contrast to the 9s, these students' inner drive seems to stem more from a sense of competition than from a love of learning for learning's sake. For example, an academic 7 might underachieve in certain subjects on the grounds that proper motivation was not provided by the instructor or class environment. Though many students in this category perform extremely well in high school (roughly top two to five percent in their high school), lower performance could result from a sense of boredom experienced in a class perceived to be below their level. However, like academic 9s, these students pursue subjects beyond their high school classes, take college classes, follow up their academic interests through projects and research, and can be top students in certain subjects. In short, academic 7s are likely to make a big contribution intellectually to their college class.

A 5 ranking. Students in this category are considered to be average in the Ivy League pool of applicants. They are still impressive performers who might look very strong on paper: captain of a sport, high school rank within the top 10 percent, fairly high test scores, advanced classes, and so on. What might be missing in the case of these students is initiative, particularly in following up outside of class on exploration of subjects that interest them. They tend to lack the creative, intellectual spark. Academic 5s can be perceived as very diligent and dutiful students who possess a tremendous work ethic but lack the intellectual edge that can be seen in the case of 9s and 7s. The actual motivation for a student in the academic 5 category may not be clear—rather than love of learning, or the fascination with a particular subject, is it the thrill of besting their classmates that inspires them? One gets a sense that most of what they have done—the record of their achievements—has been geared toward getting into the “right” college. Still, these students are clearly capable of doing the required college work and do contribute to the life of a top college, as well.

A 3 ranking. Academic 3s represent the solid student who does fairly well in school (typically top 25 percent) in a variety of honors classes, AP classes, and some regular courses. However, the student does not stand out in any particular subject or area. In the case of 3s, there is little evidence of seeking out challenges or pursuing knowledge beyond the bounds of the classroom. At the end of a high school career, the student's true interests remain undefined and perhaps even unexplored. It is unclear what students in this category would add to the life of the college.

A 1 ranking. Academic 1s are, simply put, not competitive candidates for admission to an Ivy League institution. Typically, these students are taking light course loads compared to their classmates; they fall below the top 40 percent of their high school class, show little real interest in academic study, and do not display the kind of potential to contribute to the class that is typical of the higher stanine students. The academic 1's performance indicates little academic potential, which might be evidence of the fact that his real talents lie in another area.

To compare these descriptions to those of another Ivy League school, let's look at Princeton's 1–5 scale. Fred Hargadon, the director, has described their highest rating, a 1, as someone who has five or six test scores over 700, probably a 4.0 GPA, and at least twenty solid academic classes. An academic 2 rating represents a profile lower than a 1, and so on down to the lowest, 5. He estimates that 55 percent of all applicants to Princeton fall into the category of academic 2s and 3s, whereas only about 10 percent are academic 1 s. * Notice that even without basing their ranking scale on the AI, test scores and high school grades are still the primary determining factors in the academic ranking. To be an academic 1, the student needs many test scores over 700.

FINE, BUT WHAT USE IS THE AI?

Remember, only the Ivies calculate Als, since the formula was invented to compare athletes in the same league so an academic standard could be upheld. Theoretically, the AI is only for athletes, but thanks to computers, it is relatively easy to compute an AI for every single student who applies to any Ivy League school. After all, the AI is supposed to be a formulaic method for comparing students from different high schools around the country against one uniform scale. So why not use it for non—recruited athletes, as well?

Let me be clear about the fact that not all the Ivies base their academic rankings directly on the AI as Dartmouth does. (Some do: the University of Pennsylvania uses the same 1–9 scale as Dartmouth does, also using the AI as the determining factor.) In fact, some of the Ivies do not even bother to compute an AI for every student. Why, then, is Dartmouth's AI-based ranking system useful to students, parents, and counselors as an approximation of the chance for admission at any highly selective college?

I would argue that if you were to look at those students to whom the Ivies assigned high academic rankings (using the descriptions that I have provided), there would be an extremely high correlation between high AI students and highly ranked students on each Ivy scale. This is because all the Ivies have nearly identical standards for evaluating their applicants, and these standards put a premium on test scores and class rank, as can be seen in the Princeton example. Even if the actual AI ranking system was not used, the Ivies cannot and will not change their basic system of evaluation because it is based on academic performance and, by definition, must be determined using this criteria.

This correlation is borne out by the many students who are accepted both to Dartmouth and to the other Ivies to which they applied. In the majority of cases, a student who is accepted by Dartmouth will be accepted by Yale, Princeton, Brown, Columbia, and so on. Conversely, it is rare to find a student who is rejected by Dartmouth but accepted by Yale, Harvard, or Princeton. Since the University of Pennsylvania and Cornell are slightly less selective, you might find students rejected by Dartmouth but accepted by Cornell and Penn, but you will rarely find the reverse. In fact, even though the other highly selective colleges, such as Amherst, Williams, and Swarthmore, do not even have an AL you would find the same very high correlation. Thus, most students who are accepted by Dartmouth will also be admitted to most of the other highly selective colleges.

Even in non–Ivy League colleges, which do not use the AI, other numeric systems are employed. For example, Georgetown uses a similar ranking to the AI, but its ranking system gives more weight to class rank than to testing, unlike the AL Its system is arguably fairer (and closer to the highly selective colleges's public declarations that high school performance is more important than testing) than the Al because Georgetown does not face the inconsistency problems involved in the different ways the CRS can be calculated. It uses only the numerical scale if the student has an exact rank. If the high school reports GPA or anything other than rank, the formula is simply not generated and not used.

In light of the extremely high correlation with regard to admission to many top colleges, we turn to Dartmouth's 1–9 academic ranking scale, which is based on the Al. The first reader to look at the folder would see the AI printed on the front and would then have to assign an academic ranking manually. For the class of 2000, these rankings were as follows: 1: 179 and below; 2: 180–188; 3: 189–199; 4: 200–209; 5: 210–215; 6: 216–220; 7: 221–224; 8: 225–228; 9: 229 and above. Because of a small change in AI calculation (too small to warrant a full explanation), the scale is slightly different for the class of 2001 and beyond: 1: 180 and below; 2: 181–192; 3: 193–202; 4: 203210; 5: 211–215; 6: 216–220; 7: 221–224; 8: 225–229; 9: 230 and above.

I have provided a list of acceptance rates by academic stanine (Dartmouth refers to these rankings as “stanines”) for the class of 2000, for which Dartmouth received almost 11,400 applications: Academic 9s were admitted at a 94 percent acceptance rate; academic 8s were accepted at 92 percent; 7s at 76 percent; 6s at 52 percent; 5s at 25 percent; 4s at 11 percent; 3s at 7 percent; 2s at 5 percent; and is at less than 1 percent.* Note the high correspondence between high AIs and high acceptance rates.

Even more interesting is the distribution among prospective applicants. Of the almost 11,400 applicants who applied for the class of 2000, only 2.2 percent were academic 9s; 2.7 percent were academic 8s; 4.6 percent were academic 7s; 7.5 percent were academic 6s; 11.8 percent were academic 5s; 22.5 percent were academic 4s; 21.7 percent were academic 3s; 12.3 percent were academic 2s; and a whopping 9.9 percent were academic 1s, of whom Dartmouth accepted one student. (As you will see in chapters 11 through 16, this student would have had to have been in a special category.)

This means a full 44 percent of the applicants were only academic 3s and 4s—very few of whom were admitted. Dartmouth considers the average (in its pool) applicant to be an academic 5, and even in this group, the acceptance rate is only 25 percent. The most numerous group is that of the academic 4s, of whom only 11 percent are accepted. I can say without a doubt that academic 4s are usually not weak students—typically an academic 4 has solid 600 scores all around and is ranked in the lower part of the first decile. The overwhelming impression is usually one of solidity—a solid but not exceptional student with particular strengths in one or more subjects, some decent leadership abilities, and strong recommendations. The average AI for the matriculating members of the class of 2000 at Dartmouth was 211. Of the 11,389 students who applied, the average AI was 200.

By now, you should have a sense of just how competitive it is at the most selective schools and how a few extra points in the CRS, and therefore the AI, can turn a marginal candidate into an easy admit. Guidance counselors should be aware that how they report students' ranking can make the difference between ac ceptance and rejection. The AI is the crucial number, since it affects the academic ranking. As we have seen throughout this chapter, the difference between an exact rank and a decile rank, or between a straight GPA and an exact rank, can result in a CRS difference (hence, an AI difference) of as many as twelve to fourteen points. Looking at the distributions above, even a twelve-point difference in AI can be the difference between an academic 8 (admitted at a 92 percent rate) and an academic 5 (admitted at only 25 percent). This difference cannot be understated. An academic 8 will almost always be accepted, while an academic 5 will probably not be accepted.

Many people assume that being valedictorian will virtually guarantee acceptance into any Ivy League school, but that is just not the case. Although typically 40 percent or so of the freshman class at Dartmouth is ranked either number one or number two in high school, each year Dartmouth rejects almost as many number ones and number twos as it accepts. Look at Princeton's class of 1999: Princeton received 1,534 applications from those who were ranked number one in their high schools, out of which only 495, or 32 percent, were accepted.

I can also tell you that after decision letters are mailed out, colleges get several weeks worth of “Why R” calls (“Why did you reject my child?”) and they almost always come from the academic 4 or 5 group. From the parents's point of view, their child has nearly all A's, highish test scores, and a fair amount of leadership ability. But, as you can see from the averages, the average SAT scores are over 1,415, the average SAT Its are usually in the high 600s to mid 700s, and roughly 40 percent of the admitted class is ranked number one or number two in their high school class. The competition is indeed fierce, and most academic 4s, although not at all weak, will not make it into the class. In fact, almost 90 percent of them will be rejected, and of the 10 percent that are accepted, it is fairly certain they will have something very strong going for them in another area, which might not be entirely merit-based. Note also that together academic is and 2s comprise about 22 percent of all applicants, but most of these are low enough in the pool that they warrant only a cursory read by two readers. When people ask me, “Well, doesn't everyone look strong?” I have to answer no, because academic is and 2s really do look significantly lower, particularly in testing, which tends to be in the 400 to 500 range.

WHAT TO DO IF YOU ARE AN ACADEMIC 1, 2, OR 3

A full 44 percent of all applicants at Dartmouth (and by extension, a very similar percentage at the other highly selective colleges) fall into the academic 1, 2, or 3 category, of which not very many are accepted. If you fall into this category, what are some of the compelling reasons admissions officers might find to admit you and what can you do to strengthen your case despite the long odds?

• Some students accepted in this category come from extremely disadvantaged backgrounds. Usually neither parent will have graduated_ from college. Sometimes, the student is the first in his family even to graduate from high school. A student in this category, despite low test scores, would have to show exceptional academic promise and proof that he went beyond his immediate surroundings to seek challenges.

• Some of these students will fall into one or more of the special categories to which I devote the last few chapters. For example, the number-one-rated male ice hockey recruit might fall into this category, but he still must show some academic signs of life.

• Students in this category will need truly inspirational recommendations from teachers and guidance counselors. They will also need some evidence (a regional science competition, research out of school) of exceptional academic achievements outside of high school, even if high school rank and scores are not top-notch.

• Students will need to write a truly extraordinary essay. Sometimes students will elaborate on their humble family backgrounds. Love of learning must come across.

• Grades must be improving dramatically and the student must be taking a challenging course load. Sometimes a student's CRS will be low because he had a weak ninth-grade year. Admissions officers will look closely at junior and senior grades.

• Students should have significant leadership and extracurricular involvement either in school or out of school. The colleges must be able to say to themselves, “This student would be a significant addition to our campus.”

• Some students in this category will have tremendous talents, probably national-level, in a particular field—an Olympic athlete, a musician involved in a nationally ranked orchestra, a Westinghouse science winner.

Students in this low academic category are somewhat of a long shot for Ivy League schools, but there is always the possibility of making oneself stand out enough to warrant admission.

WHAT TO DO IF YOU ARE AN ACADEMIC 4, 5, OR 6

Forty-two percent of Dartmouth's applicants fall into one of these three categories. Though I will group them all together in order to make some general suggestions, note that academic 6s have roughly twice the admission rate of 5s, so there is probably a subgrouping here of academic 6s, and then academic 4s and 5s.

• All the essays and other written information should showcase the student's academic strengths and intellectual ability.

• Teacher recommendations and guidance counselor recommendations should be outstanding. They should give specific examples of how the student has been a high-impact player in high school and how they think the student will continue to be. Many of the students in this category who are rejected tend to be very diligent students who show no real academic spark. Again, students should make sure they are vocal members of their classes.

• Students should make sure their grades are going up and that they are taking the most challenging courses. Sometimes students in these categories will be turned down because officers note that they are taking fewer challenging classes than their classmates.

• Students should show some degree of academic initiative—summer programs, independent research, regional awards, awards in the high school, and so on.

• Love of learning and intellectual potential should be evident throughout the application.

• Significant in-school or out-of-school leadership or talents such as sports or music should be evident. One reason students in this category get turned down is that they have no leadership ability at all (member of three sports teams, but never captain), no work experience, or no real talents to add to the class.

• Students should have strong character and personality. Teachers should comment favorably on a student's personal attributes. Remember, though, academics still account for about 70 to 75 percent of the admissions decision, but students in this category need strong extras and personal strengths in order to stand out from the pack.

• More than any other group, students in this category are aided by being in one of the special categories that will be discussed in chapters 11–16, because they are all “admissible,” and in close cases, a tip factor could really shift the balance to an “accept.”

If you fall into this academic group, you more than anyone need to focus on the following chapters so you can make sure you do everything in your power to put together the strongest possible application in every respect. Cases in this category can go either way, so the more you know about how to present yourself, the better your chances will be. Students in this category will be the ones who benefit the most from this book.

WHAT TO DO IF YOU ARE AN ACADEMIC 7, 8, OR 9

Most of the students (only 10 percent of the overall applicant pool) who fall into one of these academic categories will be accepted to any or all highly selective colleges they apply to. As general advice, students in this category should follow the advice for 4s, Ss, and 6s. The important thing to remember is not to rock the boat. You will be accepted unless you do something dramatically wrong on your application. For this reason, I have included specific reasons why a student in this high academic category might get turned down by a top college.

• The student shows signs of intolerance or bigotry.

• The student gets very negative character assessments (more in chapter 9) from one or more teachers.

• The student does absolutely nothing or the bare minimum outside of high school. There is no evidence that the student would add to any part of campus life other than the classroom.

• The student has some kind of honor violation or serious disciplinary problem.

• The student's essay and supplementary written material is poorly done and shows lack of academic strength.

• The student gets extremely low interview ratings on either his on-campus interview or alumni interview.

• The student is described by all as extremely diligent but not very interested in learning for learning's sake.

For the most part, students in this category should be accepted to many top colleges unless something is amiss. These students also will benefit from learning in depth about the reading process so that they will better understand what can go wrong in the reading of their applications.

Before concluding this important chapter, I want to mention an almost philosophical point about reading files. Much like using a particular method of literary criticism method to read “against” the fabric of a book, admissions officers see the AI (or if they don't see the actual Al, they see the GPA, rank, and test scores) and read against it. For example, if they pick up a folder that has a 230 Al, they have certain expectations: This student should show a love for learning, be exceptionally bright, have very high grades, write very well, and have extremely supportive teacher recommendations. At the same time, the readers are distrustful of the Al. Is the converted rank score overinflated? When officers see a very low AI, they will look closely for mitigating factors, such as poor background, exceptional hardship, or any other information that could boost the student despite a low AI.

Even if the Ivies were to abolish the Al formula someday, they will still use basically the same process for determining academic merit. Scores and class rank will still be paramount, as will intellectual curiosity and love of learning. The Al is only a vehicle for evaluating underlying academic qualities. Knowing your Al and approximate academic ranking will give you an idea of what your chances are of being accepted to the most highly selective colleges, and what concrete steps you can take to improve those chances.