Given the enormous expectations that our clients and society as a whole have for the houses we architects design, I’d think that uninitiated architects would have some trepidation about wanting to design houses as a part of our professional practice.

For those of us who primarily work in the commercial or institutional design world, the chance to interact with an end user who can make decisions based on personal taste (and whim within the budget) and not based on a business case or financial return is very attractive. It is a big part of why our residential design practice has become so much fun in our office and why we put up with the challenges to continue doing it. A look at the professional architectural press and the related home design and shelter publications reveal that houses generate a great deal of interest, a completely understandable situation. The house is an attractive and easily comprehensible building type—both for us as professionals and for the public. Everyone lives in some kind of housing, and being aware of the opportunities and aspirations available is exciting and interesting to consider, no matter the person’s economic status.

Most residential projects provide the opportunity to design a building with a relatively high cost per square foot when compared to other project types, allowing you to work with materials, details, and finishes often not available for consideration in the corporate and institutional world. Houses are one of the last places in which certain building techniques, technologies, and finishes still have an acceptable place, where building codes and rules for accessibility are not integral to all your design considerations. These concerns are the legitimate responsibilities of our profession, but in designing a single-family home they are typically not a consideration unless made a priority by the client. In designing a house, you have the opportunity to utilize small and often carefully detailed components that can be celebrated at this relatively small scale, but would be potentially inconsequential in a larger project. In residential design, you can help your clients select and work with finishes that have neither the durability nor the economy to be used in larger projects. The only justification required for any material selection is that your clients have a fondness or inclination to use those things in their personal environments. One analogy I use when explaining the design possibilities inherent in residential architecture to architects who have never designed a house, is that you are treating a whole building as if it were the lobby of a commercial office suite. It’s the place where multiple finishes, carefully chosen lighting, and emblematic details are all brought together for optimum effect.

The complexity of most nonresidential building programs is reflected by the multiple issues that have to be incorporated into their design (codes, entitlements, budgets, schedules), when compared to houses, require straightforward programs and (relatively) small scale. Houses, even very large ones, can still be conceived and executed by one design professional, the full professional services required encompassed as an effort of one thoughtful practitioner. From a programming point of view, the varied domestic spaces that make up a house are usually immediately comprehensible, and most clients have a basic understanding of their function and use. The spatial adjacency and flow of these spaces are by nature flexible, and the variety of compositional alternatives to take advantage of a specific site and the needs of the user will guide the choices you make when organizing the work.

To comprehend the design of houses as an area of professional practice, it is good to start by considering some basic questions that reveal how specialized a residential practice really is. For those architects who have never designed a house, viewing houses in magazines and books gives the impression they are all exercises in architectural creativity paired with patronlike clients to achieve iconic results. In reality, residential architecture offers a full variety of client expectations, program needs, and budgets, analogous to the conditions that come to bear on any commercial or institutional structure. The questions concerning residential architecture and your suitability to engage in its practice are largely philosophical, but they speak to the core of how truly specialized single-family residential design is and the conditions you will have to deal with and overcome to be successful.

The first question deals with the place architects have in the design of single-family homes in U.S. society. Do you think that the quality of urban and suburban life in the United States would be better if we (licensed architects) designed all the houses built in this country specifically for the sites and the programs of the individual homeowners?

On the surface the answer to this question is a wholehearted and emphatic yes. If we as architects had the opportunity to design houses for everyone, it would probably be a more thoughtfully conceived and perhaps (depending on your aesthetic viewpoint) more beautiful world. It would also encompass a reality of fewer people living in houses, the added cost of our fees, and the cost multiplier for constructing unique single-owner designs which would probably allow fewer people to own homes. Places where architectural control and individual designs are required to build a home are usually very expensive, places only the wealthy can afford. Think of Seaside, Florida, with its award-winning plan and wonderful collection of houses. An older, but just as valid example is Oak Park, Illinois, where so much of Frank Lloyd Wright’s early work was built. It is hardly an affordable neighborhood; it was never intended to be. The clients for the houses designed by Wright and the other architects working in Oak Park at the time were all solidly upper middle class, with the wherewithal to buy a lot in an expensive garden suburb and have a house designed and built specifically for them. Most major metropolitan areas around the United States have neighborhoods like this, and they continue to be the places where residential architects have the greatest ongoing opportunity to practice. The real estate values are tied to the overall transcendent qualities of the neighborhood, and the housing stock is constantly in transition, subject to remodels and replacement.

As discussed earlier, the idea of everyone living in an architect-designed house is a fantasy. And even if it could come true, we may not be the only people qualified to determine what a house is for anyone, let alone for everyone. Personal taste aside, when choosing how you want to live, the individual identity of the end user is an important part of the design choices. This individual determination of the “look and feel” of the places we aspire to live is an integral part of the American Dream. Inherent in this vision is the corresponding opportunity to live in a house that reflects your aspirations, within your financial means, and this consideration suggests that there would always be a diversity of styles, sizes, and expressions within a wide range of tastes. Wealthy people with tremendous means can just as easily be the clients for badly conceived and poorly built houses as can those of modest means who choose to buy smaller but correspondingly badly designed or executed homes. We have all been in the modest homes of people of great refinement who with simple means convey lovely taste, all rendered with inexpensive, even cast-off furniture and decorative objects. Such individuals would make wonderful clients for an architect, but if they cannot afford to pay for the architect’s services, it doesn’t matter. The old remark that money doesn’t buy taste is absolutely true. It is also true that the same money can pay you to work as a professional doing ugly things.

If you are reading this book, I can assume you are an architect or someone interested in working with an architect (or at least someone who aspires to be sensitive to design), and the next question gets to the heart of who we can expect to work for at a very personal level. Do you live in a house you designed from scratch and had built from the ground up (not remodeled or added onto)? Once people meet you and find out you’re an architect, do they inquire if you designed your own house? Why don’t all architects live in houses they designed and built?

The answer is pretty simple; it is the cost, which for any house is expensive, but for a one-off architectural design is even more so. We simply cannot afford to design and construct our own homes; they are too expensive, and like most people, we don’t have the means.

This situation represents a key paradox to understanding the professional opportunities open to you as an architect: If we architects believe that we could make life better for all those around us if we designed more of the houses people live in, then why are we not living that vision ourselves? If we designed houses for ourselves, at least the fees would be free (assuming we do them without charging ourselves)! We are not doing so for the same reason everyone else is not—we cannot afford it either.

How many architects do primarily residential design as a practice? A lot. The American Institute of Architects indicates that roughly one-half of its membership is sole practitioners, and many of these are engaged primarily in residential design, whether from the ground up, restoration, remodeling, or additions. Many architects are employed by the merchant builder housing industry, either directly in their companies or with firms that provide design services to them. Architects do indeed design a great deal of the housing stock in the nation, although we neither admit it nor acknowledge it.

The design departments in the major home building development firms in the United States are run by registered architects. They were responsible for designing 1,930,000 houses in the United States in 2006. Very few of these were designed specifically for a client or site, and many of the designs were constructed multiple times using prototypes; but still they were the work of architects. It is a myth that merchant housing is all designed by “building and residential designers” who have none of the architect’s specific skills or education. Professionals like us are actually creating Le Corbusier’s “Machine for Living”—housing that is financially accessible to a large portion of the population in large volumes around the country. We in the profession are closely involved in the creation of those merchant builder housing types that we love to hate, and even more ironically, we live in them too! A decidedly unscientific survey of architects in Dallas, where I live, including those working in my office, indicates that architects buy existing or new homes in the suburbs for the same reasons most Americans do—these are houses with amenities they want at a price they can afford and with access to good schools. Many may choose to buy these houses in an older, inner-ring suburb, but architects buy merchant-built tract housing just as everyone else does.

New affordable houses with the amenities people want are integral to the mission of the home building industry. The products are tailored to the marketplace through surveys and strategies guided to attract potential homebuyers and make them buy their houses. The overall quality and the detail of the finished work are not the primary concerns of most of these buyers, another by-product of our consumer society, which is focused on fashions and trends important or promoted at the moment. Few people buy homes with the thought it will be a place where they will live for the rest of their lives. The historical pattern of ever-increasing home prices has made a house just another investment, one that people own until they can move up to the next model. In a sense, the housing business in the United States has become much like the auto industry, geared to perceptions of newer and better products through a program of built-in obsolescence. It allows home builders to provide the maximum amount of square footage, paired with the required amenities, to make products attractive to the largest possible segment of buyers.

Although we probably don’t perceive it this way, our professional services as architects are too expensive, and in the framework of traditional practice (with all the phases of services we historically provide) we are really not positioned to be the best providers of housing for most people. No matter what their level of financial stability or their commitment to a good and a well-thought-out house, only a very small number of people can actually be considered as a market for our services, and identifying and contracting with these relatively few is a challenging prospect. Internalizing this fact is also an important reality.

If you want to design and build single-family houses, you need to understand who are the potential clients for your work. Many architects specialize in houses, and it is the majority of work within their practices, perhaps the only kind of projects they do. Some architects, myself included, design houses as one component of the mix of projects in their firm.

For many architects an opportunity to design a single-family home is an obvious and early first opportunity for working independently and beginning to create a professional portfolio of work. Stereotypically, this first house is often for a family member or a close friend. Most residential clients don’t expect or require you to have the kind of office infrastructure and staff you need to support many other project types, hence the number of houses done by architects while moonlighting away from their regular employers. Houses, as a project type lend themselves particularly well to small firms or even single practitioners where only one person has a day-to-day relationship with the client. The design of a house can be approached from a small office suite or even a home office; the only equipment necessary is a computer or a drafting table. Rarely do the insurance requirements common to commercial or institutional projects apply to single-family houses, and many clients don’t know to expect you to have professional liability or errors and omissions insurance characteristic of the contract requirements for many projects. These considerations render the economic factors necessary to start a residential practice modest and attractive, a practical way to start an architectural firm.

Architects who are practicing as a principal, have an established architectural practice in another area of specialization, and currently have successful relationships with clients who know and enjoy working with them are probably the best candidates for initial residential design opportunities. In my case, clients for whom we had designed multiple retail stores asked us to do their new home. They knew who we were and how we worked, felt good about the quality of our services, and assumed it was logical to ask us to do their house. That initial house led to others, and the residential side of our practice evolved from there. It was also telling that these initial clients would represent the profile of virtually all our residential clients, a fact confirmed anecdotally when we visit with our peers and ask them for whom they design houses. The similarities are strong enough that I can outline them here and use them as a guide for how to target your efforts to begin work with them.

The people you will need to identify, so you can communicate your architectural abilities and create a residential practice, fit within a relatively small demographic slice of the U.S. population. Not surprisingly they will have a high net worth, for the most part be married couples or life partners, with professional or entrepreneurial backgrounds and advanced education. If you don’t know or work with these people in your day-to-day life, you will probably not find an opportunity to design houses. People of modest means don’t hire architects. People who lack abundant disposable income don’t hire architects. People who want instant gratification don’t hire architects. People with modest educations who are not necessarily intellectually curious and enjoy working through projects in a process to achieve desired results don’t hire architects. Even if you take all the affluent people you could identify as a group, not all will have the inclination to engage with an architect to design their homes.

To test these assumptions, think about the professionals outside your practice life with whom you usually work. Here I am referring to professionals as people with specific educational backgrounds who hold certifications or licensure that defines them as experts at an area of service for which they get compensated, in this case folks who do not provide a tangible product for their compensation. Like most Americans, you probably have a relationship with a doctor or a dentist, two examples of professionals who provide services for fees. Further you may have an accountant who provides you with bookkeeping and tax services. If necessary, you may engage a lawyer for business advice or family legal situations, again another professional with whom most people will interact at some time in their lives. Not so for architects. Most people, the vast majority, will go through their lives and never work with an architect. They won’t be building anything so it won’t be necessary for them to meet or have a professional relationship with an architect. This gives you a realistic context to understand how really specialized your profession is and just how relatively little opportunity there is for you to practice, especially for private clients designing a home.

So what makes someone decide to choose an architect to design a house for him or her? In my experience it takes three things for a client to be willing to engage an architect to design a house: ego, patience, and money. Without all three of these in largely equal measures, that person is probably not the right candidate for you to work with. Why?

First, consider ego as a client characteristic. In the case of clients for residential design services, this is not a bad or undesirable thing. Regardless of what motivates them, be it the perception of their peers or just their own need to create something unique, without a strong self-image clients would not try to create houses for themselves in a process that requires their input and approvals. They must have a large enough ego to believe that there is not an existing house available on the market, in the location they want, that they can buy and that will fill their needs. They have to believe that this accommodation of their program and desires can only be accomplished by working with an architect to design the “perfect” house for them.

Second, clients have to have abundant patience. They need patience because the process takes time. They have to realize and accept the direct correlation between the amount of time invested by you and your clients and the quality of the solution and how they will feel about it and the level of ownership they will have in the final product. Once you have finished the design and documentation for the house, then they have to wait to have it priced, select a contractor, and go through the construction process. Our experience has shown that an average of 30 months is required to design and build one of our houses. It is not unusual for it to require even longer—one recent project took over five years to design and build.

Third, clients have to have a lot of money (of course a lot is a relative term depending on the project and location). Money is critical to the process, but without ego and patience, it alone is not enough to create a successful house. Clients must have the resources to pay you to provide the services required to meet their needs and expectations, and then they have to pay for the house. In Dallas, where I live, the cost of an architecturally designed house per square foot from the ground up usually runs 50 to 100 percent over comparable square footage costs in upscale custom home subdivisions. For some of the people who could otherwise afford to be potential clients, this fact alone would make them skeptical of the value of the services of an architect.

Many architects do not want to design houses, often for reasons that include the perception of the inherent wastefulness of single-family homes, their relatively large ecological footprint, and their diversion of resources from other more necessary building types. If you are inclined to think this way, knowing that your opinions may not be appreciated by those commissioning you to design a house, you should probably stay away from new single-family design. If you desire to make an impact on society by emphasizing your understanding of sustainability and ecological principles through your design efforts, then single-family houses are not the best use of your passions and skills. It does not mean those elements are not integral to a responsible architect’s interaction with all her or his clients, but in this case you may be disappointed by the lack of priority for these kinds of issues by your clients.

Something else is needed if you want to design and build adventurous, artistic, and more edgy work: You need clients who will support you in fully exploring your ideas and theirs to make something truly unique and special. They must want to compensate you to follow a creative path, perhaps of their own direction and with their full engagement in the process, to provide a house that satisfies their desire for something unique and iconic. These clients are rare and need to be treated for what they are—patrons who deserve special treatment and all the best your efforts can provide. We have had more than our fair share of these kinds of clients, with their willingness to allow exploration of spatial and detailing invention to the fullest, no matter what their relative program or budget. These projects are at once liberating and scary, carrying tremendous obligations not to squander the artistic opportunity or utilize the resources to the fullest in creating your design.

The likelihood that you will have the chance to work with clients like these is directly linked to how you approach each of your residential design projects and the opportunity you make of every commission. Depending on your professional goals, this approach involves taking a very long view. You have to accept that you may not be able to maximize the potential profits in every project. You will be making a decision to defer these tangible financial gains in service to a longer-term professional reputation. But once you accept this idea, you can focus on work of steadily increasing quality and construction cost which will ultimately justify higher fees. Deferred gratification can ultimately be very satisfying, but it includes an element of uncertainty.

Architects with clients who commission them for design projects based on their reputation and portfolio of completed work usually begin professional practice with fairly typical commissions where they make extra efforts and use their talent to transcend the program and optimize every possible opportunity to do something special. The reputations of these architects are built one project at a time, and bring the reward of working with design-oriented clients who are excited about the process of engaging with an architect to design their home.

Many of the prominent architects whose work is frequently published have reached a stage in their professional careers where they attract only those clients who come to them because of their reputations. By implication these clients expect to support the architect’s design efforts, resulting in very special homes for which their patronage will be recognized. This is the ultimate way of obtaining discriminating clients who have the inclination and resources to be patrons, having them coming to you because of your reputation.

Despite the potential artistic freedom that single-family homes provide, they are not all necessarily the place for you to be overly experimental or to explore your own design interests. Inevitably, many of your potential clients will want you to design a house in a certain historical style, or with very pedestrian design goals. If you are not fully prepared to entertain their goals for the project, taking on these clients requires tremendous intellectual honesty and introspection. During your initial interviews they will usually tell you up front what they are looking for; some may even have books or magazines with specific houses or, even worse, various elements of houses they fully expect to see incorporated into their new home. If you take on the commission, you need to make sure you can meet the client’s design and aesthetic goals without compromising your own in an honest and straightforward manner. Clearly you may not have either the artistic inclination or the skills to do houses in a traditional or historic style; but if you want the project, for whatever reasons, you have to be prepared to subordinate your predilections to those of your clients.

Often there are business reasons with potentially long-term ramifications for accepting or not accepting the commission for a house for clients with preestablished design goals. You need to understand that the commission may come with conditions you are uncomfortable with or unwilling to accept. It may require you to think through the commission itself and assess the pros and cons of its undertaking as well as possible outcomes for you and your firm. Further, it is worthwhile to explore each of these possible outcomes and fully understand their potential for your practice.

It is useful to understand why the potential client has indicated an interest in selecting your firm to design the new house. Perhaps you don’t have just what they would envision themselves wanting in your portfolio, and you may wonder what the attraction was. In the course of the interview process, you must have convinced them that you embody the professional characteristics of the person they want to employ. Consideration of the services you can provide, the level of your involvement, and the overall quality of your work have inclined them to commission you. This should be flattering, an extreme compliment regarding your approach and reputation, at least allowing you to consider the possibility that the clients, if not the project, represent.

It is always good to consider the source of the referral when you are considering a client. If the potential clients were referred to you by another client, one for whom you did a stylistically different house, this suggests that your clients recognized the value of the work you did for them, despite the stylistic differences, and were willing to suggest and endorse your firm to their acquaintances. Think about why they selected you, especially if you don’t have a portfolio of similar houses. Again you have set an impressive standard with your services, recognized by those you work for, that transcends your artistic inclinations.

A good question to ask yourself in evaluating whether to engage in a project is, does the potential client offer a relationship you and your firm would like to have for other reasons? Despite the fact the project may not meet your criteria for an acceptable addition to your portfolio, the clients may have other things to offer that may make working with them attractive. As noted above, in most cases the possible clients for your work are limited to a small demographic group, and the greater exposure you have to that group, the better your chances of being considered for other projects. Given that residential design work is sometimes a way to create relationships which can lead to other project types, it is good to consider whether the relationship you would create with this client could potentially allow your entrße to other projects or client referrals in the future.

At various times in your career, projects will present themselves when your firm’s fortunes are such that you just need the work. At times like these, you may not be in a position to turn down the opportunity to work with a paying client on a real project. If business at your firm is not good enough to tell the client no and your moral compass will still allow you to give the project your best efforts, then consider taking the project. Often a project doesn’t have to be valuable just as a design opportunity. It can be a vehicle to refine your skills and keep the team you have assembled busy and active. In slow times as well as good times the opportunity in any project may not be immediately visible, and there is nothing to be ashamed of in doing meaningful, honorable work when you need it.

Another consideration is the very real chance that in working with the clients may develop more artistic goals and interests. Too often in our practice we have held our noses when taking on a project, only to have it turn into an exceptional experience for all the team members involved. In cases like this, architect, contractor, and most of all clients can sense the unique nature of the way the project is coming together, how really special their home will be as a place to live. Sometimes clients slowly realize the potential of architecture to provide them with much more than their initial expectations, and they allow us to design remarkable things for them, dramatically different from their initial expectations. In a few cases they have even evolved into the patronlike clients discussed earlier; but until you begin to work with them and establish a mutual level of trust, you cannot really know where the project will take you. I have been happily surprised far more than I have been disappointed with a client and a project I was wary of undertaking.

Finally, you never know when your investigations and research into more traditional architecture for one project may provide you with a way of exploring something new and exciting that will contribute to other aspects of your practice. It was designing and detailing traditional architectural woodwork and millwork that helped me to develop an appreciation for fine woodworking and joinery. That appreciation and the way we incorporate fine woodwork into our designs have been an integral part of our practice for more than 20 years. Although almost none of my work could be characterized as historical, I feel most of it is traditional in the sense it relies on traditional means and methods of construction, utilizes materials in ways that have been appropriate for centuries, and eschews newer materials for older, more tested ones. This is a direct outgrowth of working on more historical projects at an earlier time in my career and learning to understand and value traditional building methods.

Not all the architects with primarily residential practices are designing contemporary houses. It is good to keep in mind that there are more clients looking for traditional houses than contemporary houses. For many architects interested in designing houses this reality is a sad truth. But this same privileged demographic of potential clients I’ve been discussing in this chapter is often a conservative one, interested in houses that are traditional and historical, in styles that appeal to a broad cross section of their friends and peers. In most large metropolitan areas, there will be a talented selection of residential architects, doing largely traditional designs, who are available to this group of potential clients. These architects practice at an elevated level of service and design quality, and their work is superb, by any standards of evaluation. Most did not become architects practicing in this way as a default because they couldn’t get more contemporary work, but because they were attracted to more traditional domestic styles and found ample opportunity to fulfill their artistic needs and those of their clients. The architectural quality of their work is immediately visible and can easily be distinguished from that of traditional houses done by custom builders.

If the opportunity presents itself for you to take on the design of a more traditional house, then be prepared to provide the services at the highest level of professionalism. Despite your disappointment, execute your services with the same commitment to quality and detail. If you agree to a contract for a house that requires an aesthetic you don’t like and would consider treating it with less than your best efforts, then take the long view and don’t take the commission. You should never encumber yourself or your firm with clients or projects you don’t believe in, purely for the compensation. If you do take the project, remember that the client may not be willing to shift from her or his original design goals just because you “enlighten” the client on the better quality of life that a house designed using more contemporary principles can provide.

If you are too forceful with your clients about exploring another, different direction than they were expecting, you risk losing their support. Even worse, if you try to slide a more contemporary design by them by not fully communicating your design, you can create an atmosphere of mistrust and a feeling that you are not responding to their needs. From the client’s point of view, their vision of the house was expressed to you well before you signed a contract and now you don’t seem to be honoring your side of the agreement. As a professional you have a duty to serve your clients first, to provide the services they expect at the highest level of your abilities. If you disregard their wishes and create conflict over aesthetic objectives the clients have for the project, you are acting in bad faith and, by extension, providing bad service for their money. In the real world acting like Howard Roark is irresponsible. You can always seek a client who is more inclined toward your point of view, but it is wrong to try to force a client in a direction he or she does not want to go.

Remember that this thin slice of demographic pie represents a small world, and your reputation is your primary marketing tool. Many of the potential clients in your area may know one another, or at least be likely to have contact through other social or business networks. This reality, combined with the fact that word-of-mouth referral is the best source of new work for a typical residential practice, should help you understand that every client deserves your best and most sincere efforts. Bad word of mouth can hurt you, especially if you are terminated by a client who has been paying fees for work she or he considers unsatisfactory, without you being able to finish the project.

It is likely that the people you are working with will have ongoing relationships with lawyers whom they engage when they feel they are being mistreated or taken advantage of. It is useful to remember that if they can afford to hire you to design a house for them, they can and, if necessary will, have lawyers advising them on a regular basis. Your potential exposure is not just for the fees they have paid you, but potentially for delays in starting construction incurred from your slow progress on work they didn’t want done. They will now be faced with selecting and hiring another architect and moving forward from scratch, a potentially devastating charge to be leveled against you.

In residential practice you will be working for people who will not be “professional clients.” In this sense I am suggesting that for commercial and institutional clients there are usually individuals or consultants, experienced professionals who act as the client’s advocates and representatives. They will be familiar with interacting with contractors and the nuances of the construction process and will have at least a working understanding of construction costs. Most residential clients will at best have an anecdotal understanding of construction costs, suggesting it will be incomplete and potentially inaccurate. Therefore clients will rely on you to verify or create expectations of the costs for their project. Often they will touch on this subject in meetings before you are hired, and it has been our experience it is best addressed early and in a thorough manner to ensure there are no misunderstandings. No matter what the design of the house will ultimately be, one area of construction cost is disproportionately significant in single-family homes when compared to commercial and institutional projects. These are the contractor’s general conditions, and we tend to talk about them early so our clients will understand what they are and their value to the project.

Aside from the professional fees for an architect and his or her consultants, one significant component of building a one-of-a-kind house is the general conditions and other fees that go into the cost of the project which, to your clients, will not appear to be building or providing anything tangible. By general conditions we are referring here to the necessary costs of the project that are not purchasing materials, labor, or equipment used in the construction of the house, but are the costs associated with the administration and management of the project.

In our experience it is not unusual for the general conditions, overhead, and profit to be 25 to 30 percent of the final cost of the house and very often more. Numbers of this nature would seem extremely unreasonable for a commercial or institutional project, but they have to be fully understood by you and your clients to make sense in a residential context. In a commercial or institutional project, many of the costs are comparatively the same as for a house, but the house is much smaller. When these costs are concentrated over such a relatively small area of square footage, they seem to require a very large portion of the total construction costs. That is why this discussion is included in this chapter about making houses an architectural practice; the information is counterintuitive, and not realizing it will affect your design work. If you don’t consider it when first working with your clients, it will present significant challenges to you once the project is designed. This surprising but undeniable reality is another difference you will need to understand and be able to explain when making the design of houses an architectural practice for your firm.

The items indicated above that a contractor will incorporate into the pricing for the project and will typically be included in their category for general conditions are listed and outlined below. The means by which they are determined has a direct bearing on how you should be establishing your fees for service during the construction of the project. An explanation and understanding of what goes into their cost is important so the clients can fully appreciate the value they are receiving. Although general conditions are typical in most construction projects, their relatively high percentage of the overall cost of an architect-designed house makes them a major consideration in the cost of the project. They can affect other choices you will make regarding the size, materials, cost, and complexity of the house and are one more reason the construction of an architect-designed house is really only for the very affluent.

The contractor’s management of the project both from their office and on-site is a large component of the general conditions. This is typically the cost of a project manager and project superintendent during the duration of the project and is usually calculated as a cost per week or month. The project manager usually has the role of estimating the costs of the project, generating and signing contracts with the subcontractors and suppliers, and generating the pay applications and change orders. It is not unusual for the owner or principal of many smaller construction companies to play this role directly. In some form the cost of the functions they provide will be charged to the project, although the amount as a percentage of the overall cost is likely to vary with the size and complexity of the house.

To explain this in simple terms, if you pay a project superintendent $1500.00 per week or $6000.00 per month for a project requiring 12 months, the total cost to the project will be $72,000.00 (12 months × $6000.00 = $72,000.00). If that superintendent is assigned to a 100,000 ft2 warehouse project, the cost per square foot for the duration of the project will be $0.72 ($72,000.00/100,000 ft2 = $0.72 per square foot). But if the same superintendent at the same salary is assigned to a 5000 ft2 house, the cost per square foot is $14.40 ($72,000.00/5000 ft2), more than 20 times as much in relative terms! The superintendent’s duties are the same on both projects, to coordinate and manage activities on the jobsite. But on the warehouse this cost is spread across a larger area, and the impact is proportionally less to the overall budget.

This illustration is true for all the items that normally make up part of the general conditions category. It is the reason why many houses are constructed without full-time superintendents and the subcontractors are only partially managed by the general contractor, despite the importance of the superintendent to the project’s execution and quality.

A typical house designed by our firm has an 18-month construction period, and for activities on the site to be executed correctly, a full-time superintendent is usually necessary. Merchant-built developer homes don’t require or have this level of supervision; the developers manage them with personnel assigned to watch over several houses at one time, distributing the cost over many housing units. This provides one of the cost advantages of developer homes over a house you will design. In some cases the owner or one of the principals of a small construction company will manage a project directly, helping to defer some of this cost, but supervision in some form will always be a cost to the project.

If a project has a full-time, qualified superintendent and part-time project manager assigned to it for 18 months, these costs can be significant, thousands of dollars per month, many tens of thousands of dollars across the life of the project. Generally part of the cost of the superintendent will be health insurance and benefits as well as costs associated with transportation to and from the site each day.

If the house is constructed in most incorporated jurisdictions, there will be permits and fees associated with the project, and these costs will be paid by the owner as part of the contract for construction. These will vary depending on the location and the permit costs which are usually indexed to the cost of the construction. The fees will again vary with the jurisdiction, usually covering such things as specific inspections or utility connections.

“Project G and A” is an abbreviation for project general and accounting. It is the cost for the contractor’s book keeping and accounting to reconcile the books and invoices each month and pay the bills associated with the project. If the contract calls for the owner to see every invoice charged to or generated by the project, this cost will cover the assembly of those costs into an invoice or statement each month, followed by the requisite cost accounting to reconcile statements after payments are made.

Testing is a category to pay for third-party testing related to work put in place on-site by the contractor in the construction of the project. Primary among these tests are slump and compression tests done to verify that the concrete used in the foundation and any concrete slabs meet the structural engineer’s specifications. Additionally if the project requires soils preparation, this category will pay for required testing for moisture content or compaction.

The survey category can be used for several activities during the construction of the project. This has nothing to do with the site survey provided by the owner before the architect starts to design the project. This is surveying done for the contractor for the layout of the house during the foundation phase of the project schedule. Later if the permitting jurisdiction requires a survey to confirm the house is sited within the property lines or any other required setbacks, the work is done using funds available in this category.

Labor is costs for work the contractor does directly, usually things such as installing site or finish protection, fine grading, or minor construction activities. This would not be labor in the form of construction labor doing erecting, installation, or fabrication of work.

Temporary utilities are the cost of the utilities used on-site during construction activities. The contractor and his or her subcontractors will require electric power and water to build the house and will use the services available on the site during the project. If the site does not have utility services, this category will cover provision of temporary power and water until the new utilities are brought to the site and available for the contractor’s use.

Trash removal is a major task during the construction of a house. In most cases the contractor will arrange for a dumpster to be placed on the site for the duration of the project with regularly scheduled pickup and removal of the trash. Typical trash generated includes waste building products, packaging, and general litter and debris.

Temporary services cover the cost of renting and servicing a jobsite temporary toilet for use by the construction crews doing the work.

From time to time during the construction of the house, the equipment rental category will be utilized for the rental of equipment used to build the house that the contractor will need for only a short duration or for specific tasks. Generators, portable heaters, scissor lifts, backhoes, and forklifts are all examples of the kinds of equipment that the contractor will need to rent on an as-needed basis.

Cleanup is the category that will pay for progressive cleanup and final cleanup of the project. Depending on the scope and status of the project, the contractor will have personnel available to police the site and place trash and debris in the dumpster. For some types of projects, especially in neighborhoods where a clean site is mandated by local regulations, it is not unusual to have someone on-site daily. At the completion of the project, a detailed final cleanup is done before the owner takes occupancy and moves into the house. This category will also pay for that service when it is scheduled to be completed.

It is common to build a site fence both for security and to keep construction activities within a defined boundary during construction. In a typical suburban neighborhood the fence will encompass the site boundary. In most cases contractors rent these fences from a fencing company that sets them up and maintains them for the duration of the project, then removes them when the project is completed. This work is paid for from the site fence category.

Finish protection is money set aside for the labor and materials used for the protection of finished work in place while construction actives are still underway. For example, if hardwood flooring is installed, this category will provide the contractor with funds to cover it all with a protective material that can bear the traffic for the rest of construction. For projects where fine woodwork or paneling is installed, this includes temporary cardboard covers used to protect it from dust and traffic.

Scaffolding and hoists are provided on an as-needed basis to facilitate certain activities during construction. Many contractors require the subcontractors doing certain work scopes to provide their own scaffolding and hoists. Other contractors provide it for use by everyone. The final cost will be reflective of the design of the house itself, how tall the house is, and the duration of elevated activities. These will be the considerations in how the contractor budgets for this work.

Add to the list of the general conditions outlined above other similar categories of costs that do not provide pieces of the house itself. This will include the category for insurance called builder’s risk and general liability, which the contractor is contractually required to have and the owner pays for as a part of the contract.

Finally, add the overhead and profit, which vary with each project and contract but are usually somewhere between 10 and 20 percent. Between all these categories and the associated markup and fees, the cost to build a single project becomes a significant investment in time and money.

This will give you an idea of the activities and costs associated with the project for its duration. This is a clear illustration of why these categories are such a significant part of the cost of the house. Consider that if you have a construction budget for the design of a house and you begin by taking 30 percent off the top for general conditions, overhead, and profit, then you can begin to understand what portion of the resource you actually possess to build the house.

As an architect, I learned one lesson from the commission for this house, and it was the importance of a jobsite sign. Dot Brandt lived in a house across the street from a site owned by one of our clients, and for a two-year period watched their new house being constructed from her back windows. Attracted by the design of the house, she decided she wanted one just like it, only smaller. She copied our name and telephone number from the jobsite sign and called me one day, requesting an appointment for an interview. We connected immediately and she became an engaging client and wonderful friend.

Dot was a single, socially active, artistically inclined, and an accomplished woman who had successfully raised three sons, all of whom were out of college and beginning life on their own. Now living alone with her two dogs, a Rottweiler and Great Dane, she no longer needed the 10,000 ft2 house where she had raised the boys and wanted a house all her own, reflecting her interests and lifestyle, large enough for her to entertain comfortably and to host family gatherings. Living by herself, she did not need many extra bedrooms and did not anticipate frequent overnight guests. Ignoring the advice of real estate agents, she planned to build a two-bedroom house with one bedroom for herself and one for visiting guests.

Dot was also an artist in the true sense—not the dabbling, art-as-a-hobby kind of artist, but a serious artist who worked in a variety of media and needed a large studio space where she could paint, weave, work on her photography, and make jewelry. Programmatically, this space would need to be the largest in the house, but also a place separate from the rest of the house where the mess could be closed off from daily living (and entertaining).

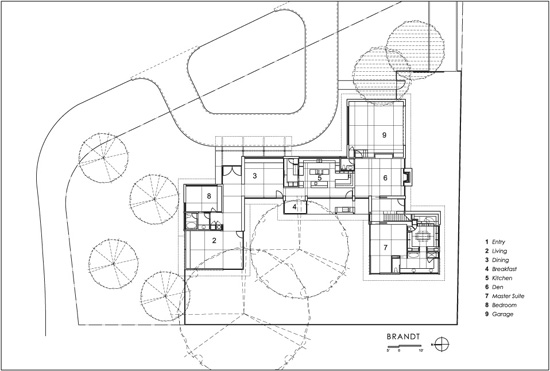

Deciding to build a new house, she first had to sell her present house, which happened relatively quickly. She then found a suitable lot with an aging house in disrepair nearby and had the existing structure demolished. The modest, but ample site was a corner lot in an established suburban neighborhood with several mature trees, and it was her desire that we integrate them all into our planning. This decision would necessitate a decentralized, linear plan of interconnected, narrow wings inserted between large trees, a wonderful starting place for the design. See Fig. 1.1.

The plan of the house was organized in a U shape, forming a courtyard around the existing mature oak trees. Most of the house is one story, with flat roofs and broad overhangs primarily to allow us to slip the buildings in under the spreading canopies of the trees. Since Dot was a single woman living alone and a sense of security and privacy were important, the outer walls of the house facing the street were rough limestone with only a few upper clerestory windows to provide some natural illumination. This limestone was cut into blocks 8 in. high, by random lengths, which created a varied pattern on the façade. As a result she could move freely around the house at night without concern of being watched. On the courtyard side the house opened up with all glass walls constructed of mill finished aluminum storefront, bringing the outside into the house. The courtyard was extensively landscaped and made a beautiful focal point for all the house’s rooms. Nestled beneath the canopies of the large trees is a covered dining area with an outdoor kitchen and built-in gas grill. This outdoor dining space is sheltered under an extension of the roof itself, which opens for convenience immediately off the kitchen. Shaded in summer and filled with sunlight in the winter, the courtyard is an attractive alternative living space and outdoor entertaining venue for Dot and her dogs. See Fig. 1.2.

FIGURE 1.1 Floor plan of the Dot Brandt house indicates the U-shaped plan organized to protect the two large existing oak trees by creating a courtyard. Each wing of the house contains a different function with the living room to one side; dining room, kitchen, and den in the center; and the master suite in the other leg. Outer walls facing the street have few windows, in marked contrast to the courtyard side which is virtually all glass. (Drawing by Zachary Martin-Schoch.)

A two-car garage with storage was placed at the rear of the site, forming an extension of the rearmost leg of the U. The garage door itself is not visible from the front of the house, but the stone mass of the garage acts to form an informal entry court for the semicircular drive. Extending into this drive is a partially covered drop-off area that accesses the front porch. Up a set of steps, the porch leads to the glass-walled foyer which is the only transparent element on the otherwise opaque street façade. This glass box signals clearly where the entry is located and provides a welcoming, cheerful foyer. Placed at an intersection of two legs of the U-shaped plan, it separates the formal living and dining spaces from the informal kitchen and den.

FIGURE 1.2 The courtyard at the Dot Brandt house showing the mature oak trees around which the whole house was planned. All the main rooms look onto this space. (Steven Vaughan Photography.)

Typical of most of the spaces in the house, the foyer is a gallery space for some of Dot’s larger paintings with high ceilings and carefully planned lighting. Beyond the foyer, the rest of the house required abundant open wall space for presenting the balance of Dot’s art. Her work is a wonderful, eclectic collection of pieces, generally large representational canvasses of friends, travel destinations, and family members (including her dogs). Very much in the spirit of a private art gallery, we tried to create serene, well-lighted spaces that would act as backdrops or framing devices to vibrant painting and sculpture. Typically the paintings and other decorative objects were aggressively colorful, so the house and its finishes were deliberately neutral, walls of either rough limestone or white plaster, sealed concrete floors.

As objects of her affection, Dot’s large dogs filled the place of her now grownup sons and were always welcome in her house, constantly underfoot. We designed the interior finishes to be durable and easily maintained. Most of the interior walls were rough Texas limestone, laid in the same manner as the exterior stone in horizontal rows 8 in. high. As mentioned above, the floors were sealed concrete over which brightly colored area rugs were laid. Interior millwork was white plastic laminate, again a surface that is easy to wipe down and clean. Countertops throughout were honed slate.

Dot is the consummate entertainer who enjoys hosting elaborate dinner parties and informal gatherings where food is always an important element. To accommodate these festive occasions, the program required a formal living room large enough to include a grand piano and a formal dining room that would seat 16 at two tables of eight. These two rooms, along with the formal entry foyer, were set off to one side of the plan to cluster them out of the pattern of day-to-day circulation in the house, which really centered on the kitchen, den, and master suite.

The real heart of the house was the kitchen and den, combined into one large continuous space separated from the courtyard through an adjoining glass wall. The kitchen itself was surrounded on two sides by a raised counter that allowed all 16 potential dinner guests to sit comfortably, overlooking the kitchen while Dot or her caterers prepared their meals. One end of this raised counter shielded a full-service cocktail bar incorporating under-counter refrigeration and an ice maker that acted as the hospitality center of the house. Within the bar was adequate cabinetry to house all Dot’s stemware, cocktail glasses, liquor, and mixers. A utilitarian wine room with its own climate control system was located at one end of the large walk-in pantry off the kitchen. See Fig. 1.3.

Connected to the kitchen and separated only by the bar was the den with its fireplace and entertainment center. The fireplace is inset into a glass wall that offers views into another smaller courtyard, freely accessed by the dogs to get out of the house. Dot frequently entertains around sporting events, so a large flat-screen television, visible to those sitting at the kitchen bar, is an important focal point of this room. All the electronics and the wiring are concealed in a cabinet in the base of the entertainment center. See Fig. 1.4.

The last leg of the U surrounding the courtyard was formed of the master suite with its studio above, the only upper-level part of the house. The master suite is accessed through a foyer of its own, separating it from the den. To close off the foyer from the den, a full-height sliding panel can be closed, securing it from the rest of the house and making it completely private. Used only when there are overnight guests or there is a need for a place to keep the dogs, this panel is concealed in a pocket in the stone wall when not in use. Within this foyer is located the stairs to the second level, which also provide access to the upper-level outdoor terrace. The master bedroom is a spacious, not overly large room, scaled to be comfortable for use by one person. Divided into two zones, one for sleeping and one for sitting, it overlooks the courtyard through a glass wall. For privacy and solar control, automatic blinds are concealed in a pocket above the windows which can be operated from a bedside control.

FIGURE 1.3 View of kitchen at the Dot Brandt house showing continuous perimeter counter for providing hospitality for guests while meals are being prepared. (Steven Vaughan Photography.)

FIGURE 1.4 View of den as an extension of the kitchen at the Dot Brandt house. The limestone fireplace is inset into a glass wall. (Steven Vaughan Photography.)

Included in this suite are a large bath with dressing area and two seasonal closets, both with packing islands that also act as dressers. The master bath is fitted with a large tub, spacious glass-enclosed shower, and significant counter space, a portion of which is for a sit-down vanity. This elongated countertop also provides a place for the display of Dot’s crystal perfume decanters. All the counters have drawer and cabinet storage below. A flush wall mirror runs the full length of the countertop and up to just under the ceiling, where natural light comes into the room through clerestory windows. The toilet is in an enclosed alcove of its own, an element common in all our projects. See Fig. 1.5.

FIGURE 1.5 Master bathroom at the Dot Brandt house shows continuous counters and clerestory windows above. The continuous mirrors allow the room to feel much larger than its modest proportions would suggest. (Steven Vaughan Photography.)

The studio, the only second-level space in the house, is organized as a large loftlike room with continuous windows running around the perimeter on four sides. Below these windows on three sides run continuous work tops with storage below. The center of the space is left free for painting easels, a weaving loom, and various art and craft projects in different stages of development. The fourth side of the studio is defined by a glass wall with French doors that open to access the large terrace overlooking the courtyard. Since the terrace is open to the branches of the mature oak canopies, being on the terrace suggests the experience of a tree house, perfect for reading, sketching, or watching the sunset over cocktails.

This house illustrates that with careful planning a house can be private, yet open to the exterior and infused with natural light. Further, it presents a house on a fairly typical suburban lot that is fully integrated with its site, makes use of existing trees, and creates a secure and comfortable environment for one person living alone.