Houses are different from other building types, and this difference extends to the ways in which providing professional services for them differ too. It may seem obvious, but there is a great deal more to understand about the design and construction process than just the differences in scale. Houses are unusual projects in many ways, but in my experience, the most significant is the way they differ in delivery of services as compared to other project types. When you are providing professional services for the design of a single-family home, the services and the manner of their delivery will be subject to several variables that affect your ability to work effectively with your clients.

First, houses differ from commercial and institutional projects with regard to their budgets. The budgets for most commercial and institutional projects are set prior to starting design and subject to close monitoring during the design and construction process. With single-family houses the budgets are more fungible, subject to discretionary changes to realize the owners’ evolving goals as the projects develop. Not including construction issues, it is not uncommon for the owners’ initial budgets to change dramatically during the design process as they explore the design possibilities for their homes through working with you.

Second, houses differ with regard to project schedule. Since the end result of the process is a house that the owners will usually plan to live in for an extended period, often for the rest of their lives, the design schedule can expand without negative consequences if the process is yielding good results. This engagement by the owner with the architect and other members of the project team often provides for additional time to explore ideas and details, especially when genuine progress is being made. Again working closely with an architect, the owners will often begin to see possibilities for further refinement in the design of their houses and may want to allow the process more time as the design matures.

Third, the team size is demonstrably different with the design of houses. For commercial and institutional projects, the owner’s team is usually larger and includes project and construction managers whose responsibility is to deliver the project on schedule and budget and to meet the specific program requirements as originally defined. The team for a residential project comprises usually only the architect and the owners. It allows decisions to be developed by consensus and usually quickly. If there are budget issues or cost overruns that arise after pricing, usually the owners were part of the decisions that led to the higher costs. Likewise, the owner will be integral in creating a solution, often without negative recourse to the architect for allowing the cost overruns to occur. This small team of interconnected and responsible parties is one of the primary attractions of working at a residential scale.

Fourth, while emotions rarely contribute to the professional relationships of the project team for a commercial or institutional project; yet there is a difference when you are providing professional services for houses. Since these houses are often a long awaited and yearned for “dream home” for many people, the design process provides abundant opportunities to elicit emotional responses from those involved. When the clients are two spouses or partners, they often have differing goals, tastes, and financial objectives for the house. Often the building of a dream house is a personal project of one of the partners, and if the other has not fully invested in the idea or comes to the process with a different set of expectations, there is potential for feelings to get hurt and egos to be bruised. As an architect, you are often the referee in this scenario, and it is a hard role to play with grace, ideally not risking the alienation from participation in the project by one of the partners.

The differences (factors and challenges) outlined above have a direct bearing on the way architects interact with clients for single-family homes and so need to be considered and accounted for in the structuring of contracts for professional services. It is critical to address these differences by creating accommodations in the contract that allow for them to happen, hopefully in a manner that won’t derail or distract from the process. Providing a framework for you to adapt to the personalities of the clients is integral to how well you will be able to interact with them and how fairly they will feel they are being treated. The typical architect’s role as defined in standard American Institute of Architects contracts does not provide for the possibility your clients may have a relationship crisis in the midst of designing their house, or that they may see it as your fault that they are over budget and cannot have everything they want in their new house. Experience has shown that if contracts for services are structured with the knowledge that these things will happen, you can usually build in accommodations from the start. These accommodations allow you to anticipate the problems as they arise within the context of your work and within the structure of the contract, gracefully, without assigning blame or responsibility.

Once the clients have determined that they want to work with you and you begin to negotiate a contract, how do you define what the services will be? The answer is, by asking the clients to assist you in defining their expectations during your early interviews. Most residential clients don’t work with architects on a regular basis. Your commercial and institutional clients understand the process, contracts, and vocabulary, but residential clients will not. Typically the new clients won’t really understand how to work with an architect, or how an architect will go about designing their house, so it is good to begin by telling them it is a process and describing the various steps and milestones that will define it.

The design process, as traditionally defined by the American Institute of Architects and widely accepted as an industry standard for the professional services provided by an architect, consists of three parts or activities: schematic design, design development, and construction documents. These are followed by the construction process, two construction-related activities where the architect has an administrative role: bidding and negotiations (with the contractor) and construction administration. Following is a brief description of each of these activities and how they relate to the design and construction of a house, most specifically from the perspective of structuring a contract.

Schematic design, sometimes referred to as conceptual design, is the process by which the initial design efforts are made, taking all the client’s input and programming, combined with the parameters of the site, an idea of the house is created. This “idea” of the house usually starts from simple diagrams of how the rooms and spaces might be arranged and includes the development of the structure itself as well as the exterior massing and “look” of the house. This part of the project is characterized by loose sketches, drawings, and documentation, becoming progressively more refined as the clients make decisions regarding the things they like and don’t like about how the house is organized and looks. At this stage in the process, the architect begins to literally shape a house out of verbal and written statements, where the architect’s skills and creativity at problem solving are most readily visible. The architect is in essence pulling a building out of her or his head and placing it before the client for review and comment.

Design development takes the consensus agreement by the project team of the layout and character of the house and begins to organize it around actual program functions, equipment, and other features required in the house. An organizing structure or envelope for the house and what it will be built from begin to be suggested and defined within this phase of the project. Ideas for building materials will be considered and rejected, and the placement of doors and windows will be resolved. In design development the house takes its form, but still without the details of every component being understood and selected.

Construction documents encompass the activity that takes the project as it exists at the end of design development and turns it into detailed, dimensioned drawings used by the contractor to price, permit, and construct the house. During this activity the consultants are brought into the process to design and document their various work scopes. Every possible decision is made and recorded in the construction documents; all the parts of the house are selected and fit within the volumes that make up the individual spaces and rooms. The structure and foundation are designed, documented, and coordinated with the architectural drawings. Details for the installation of the doors and windows, the hardware, and appliances are created and documented as part of the set that will be issued to the contractor to price and ultimately to build from. The set of drawings that is the result of this phase of the design process is what laypeople characterize as the blueprints although they have not been blue for a very long time.

As noted above, the architect plays an administrative role in the pricing and construction of the house. The architect is integral to the process, issuing the documents for pricing and supporting that effort with answers to questions and clarifications. It is the architect who will review and analyze the pricing for the owner’s benefit and advise the owner on which contractor to select to build the house.

Bidding and negotiation is the process by which the construction documents are distributed to the contractor(s) for bidding and pricing in a manner agreed to by the owners. When the pricing becomes available, it is then reviewed and approved and a contract is agreed to with the successful contractor.

Construction administration is the term for the various activities the architect provides while the contractor is building the house. This includes responding to questions and issuing clarifications and additional drawings or other materials to support or address issues that arise in the field. The architect will make periodic inspections of the site and work in progress to review the quality of the work and its compliance with the contract documents. The architect will review the applications for payment when supplied by the contractor and certify them for payment by the owner. The architect will review and approve change orders when they are required and will forward them to the owner for inclusion in the scope of work. At the completion of the project the architect will review the project for completeness as described in the contract documents and will make a punch list identifying nonconforming or incomplete work.

Our experience has taught us that a contract for services for residential design needs to address the process in terms that can be easily understood by the owners and that allow for the process to adapt as the specific needs of the clients and their ability to work with their architect unfold. It is this potential nonlinearity of the process that needs to be accommodated and integrated into the model for delivery of services.

First, we suggest that the design process only have two parts instead of three, but that all the services still be accommodated. The construction process is the same, with two parts after the design is completed and referring to pricing and construction activities. This suggests an overall process of four parts or phases, not five, and utilizes different nomenclature more accessible (and we think friendly) to clients. We use the following phases in our contract for services: design, construction documents, pricing, and construction administration.

Design for us includes programming. We feel it is impossible not to fully program the house and use the information in the design. We also combine schematic design and design development into this one activity and call it simply design. Design, defined as a creative activity, is a prolonged exercise in our design process. The owner has to first complete a programming document that fully outlines the requirements for the house. Using this document, we can then begin to organize the spaces and design the house. As the house design is refined, we continue to add to the design all the components that involve decisions and approvals by the owner, including the plan and cross section of the house, elevations, building materials, doors and windows, plumbing fixtures and appliances, and hardware. We integrate each of these items into a progressively more detailed set of design drawings until we feel all of the nonconstruction and detail questions have been answered, so that we can begin construction documents with minimal input from the clients.

Regular reviews or meetings with the clients are not typically necessary during completion of the construction documents. As noted above, the clients for houses are rarely involved in construction activities on a regular basis and, once design is done, they have very little to practically contribute to the making of the construction documents. It may be useful to have the clients review the final kitchen or bathroom layouts, especially the final cabinet and millwork organization. But typically, they will not grasp or understand the detailed documents, and knowing this, we try to minimize their involvement. When the drawings are done, we have a review meeting where we go through the construction documents in detail with them and solicit any questions or comments before we issue to the contractors for pricing.

Moving on to the construction process, bidding and negotiations is another phase where architects provide administrative services, but the owner will have little responsibility. Unless the owners want to actively participate in the pricing, this is an area where the architect will have all the responsibility and will be the primary contact for the contractors while they estimate the cost of the house. When the pricing becomes available, the owner will then be part of the review and evaluation of the cost and integral to the review and approval of the contract for construction.

During construction administration, the architect will have varying levels of activity related to the project, but will be engaged throughout the process. Communication with the contractor and clarifying the intent and contents of the construction documents will make up the bulk of the professional services. Additional administrative responsibilities for the architect will include review and approval of shop drawings and submittals and at least once a month the review and certification of the application for payment, an important responsibility, and one that should include a meeting with the owner.

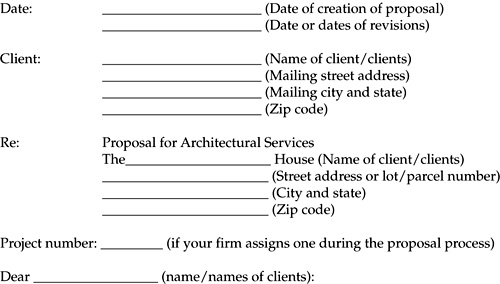

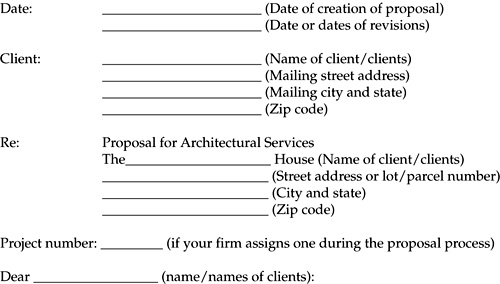

The proposal format we use when contracting for services with the owner specifically utilizes these terms to describe the categories that make up the design and construction process. Familiarizing the clients with the language used in defining and describing services we intend to provide, helps them to understand the process itself and their responsibilities. From the beginning of our professional relationship, we use these terms and phrases to discuss where we are in the process and the expectations we have for all the parties.

In addition to the design of the house itself, most architects will want to have at least some control over the design of the full environment of the interiors and the immediate site around the house. For some architects this is for artistic reasons and serves their goal of making sure all the work is harmonious with the design of the house. For others it is simply a matter of making sure that other design activities are carefully coordinated and don’t negatively impact the design and construction of the house. Either way, if we desire to take this additional work into our scope of responsibility, we need to make sure we have the fees and the client support available to do it. An example of some of these items would include

• Interior design, finishes, fittings, and furniture selection

• Pools and water features

• Landscape

• Hardscape

If you want to offer to design or coordinate the items above (or others not listed), make sure you define how they fit into the overall budget for the project and your fees for professional services. It may even be desirable to create separate fee categories for these areas of the project so it is not implied that you will do them (or coordinate them) if you are not compensated to do so.

How do you plan to charge for architectural services? Only experience will give you the answer, but here is a summary of considerations that may provide you with a practical guide when determining your services and fees.

First, different clients work at different speeds during the design process. It should be obvious that some clients will be decisive and others will have trouble making up their minds, but many contract formulas for professional services assume that clients are all the same and will interact with an architect in the same manner. In reality, many things determine how well a client will work with the architect, and some of these would include the client’s ability to feel confident making decisions and approving your suggestions as well as his or her own availability for meetings and reviews. The client’s focus and commitment will set the pace of the project and will contribute to how quickly you can move through the process.

Second, most clients are not used to viewing or reading architectural drawings and will not necessarily admit their lack of comprehension in meetings with you. If you obtain client approvals at various project milestones and you keep moving the process forward, it doesn’t mean the clients really understand what you are showing them. I get a lot of “I didn’t know we were going to do this” kind of comments in the field over fairly major things, such as window placement. This suggests that you may not know if they understand what you are showing them until later in the design process when their comprehension picks up. As the information available for their review expands, they may suddenly understand the project better and may express disappointment with an item you thought was previously approved. In the worst case, they may indicate they don’t like or approve an item now that they understand it and request you revise or change it. Depending on where you thought you were in the design process, this realization can set back the entire schedule.

In support of obtaining approvals from your clients through thorough understanding of what you are designing, perspectives and models, either computer-generated or handmade, are a useful tool. But how much in fees do you have available to do them? How will you know which clients will be helped by them, when they are really necessary? If you plan to provide these visualization tools as part of your design process, you need to accommodate them in your fee or have a way to add them to your deliverables if needed.

Third, it is reasonable that your fees have a proportionate relationship to the cost of the project. Identify the budget for the project in the proposal or contract. It needs to be a part of the conversation with the owner from the beginning and an ongoing part of the project design meetings. Setting expectations for your fees is an important step in beginning the design process, best done before you start doing any work for the clients at all.

Some possible ways of determining fees for professional services and discussions of their various possible advantages and disadvantages are outlined below.

Many people assume that architects charge for professional services as a percentage of the cost of construction. This practice was the traditional way that architects determined their professional fees, but as construction costs have increased, the cost of those fees has seemed to get much higher. In reality, if the fees are adjusted to inflation, this perception by the public is probably untrue, but it does persist. Our experience has been that basing fees for professional services on a percentage of construction costs is an uninformed and potentially risky way to determine value for your services. Since no two projects (or clients) are the same, there is usually no correlation other than that of a historic nature between fees and services. By basing your fees on a percentage of the construction cost, you are essentially gambling that you can do all the work required to design, document, and support through construction a project based on that amount. If the fees are not adequate, the criterion of a fixed percentage of the cost of construction really doesn’t allow for an expansion in scope, whether time or actual work. If you set up definable boundaries for the fees in the various stages of the project and you don’t fall within them, it’s hard to go to the client for additional compensation.

Many firms do base their fees on a percentage, but they do so by setting that percentage at a very high ratio of the construction cost. If you have developed a reputation for work of consistently high quality and for clients who build expensive projects, you may be able to demand a percentage fee that will adequately compensate you for the time frame in which you are working. But if the percentage is low, it greatly increases the risk that you will run out of fee money before the project is completed.

Another potential risk occurs if, when the project is priced, the costs come in over the originally established budget on which your proposed fees were based. Regardless of whether the clients feel you are responsible for designing a building that is outside their original budget, when they are faced with an overage, it may be hard to convince them that your fee should be revised to reflect this higher construction cost. Even worse would be an extensive period of value engineering with significant revisions to your documents which, in the spirit of a percentage fee, give you no way to recoup these costs.

Assuming the percentage fee is at a high enough number to ensure adequate compensation, one advantage of using a fixed percentage number is your ability to know at the beginning of the project your total potential compensation and to predetermine the amount of profit you expect to make. Once you have determined this number and set it aside at the start, you can tailor the delivery of your services so your efforts do not intrude on this amount. In a well-run firm that carefully monitors its work output and manages to the available professional fees, this can be an effective way to ensure profitability on a project.

Determining your fees based on an amount per square foot is also unreasonable. No two projects are the same, even with the same programs and budgets. Seemingly small variables can translate into big detailing and coordination issues. You may not be able to determine just how high the fee per square foot should be (to compensate you fully for the work you will have to do to document the house you are designing) until you are well into the design process.

A simple illustration of how a material selection could affect the amount of work you have to do to detail the house is consideration of a stucco exterior versus a masonry exterior. With stucco very few details have to be drawn, and they can be applied to many locations at the house. Stucco’s monolithic quality makes its use on exterior elevations and in details easy to apply in multiple conditions and to indicate with notes. Masonry (brick or concrete masonry units) is modular. To carefully detail the house, you will have to base your dimensioning for the exterior elevations and wall sections on careful counts of the units and the standard module heights. With masonry you will also have to design and document unit coursing, structural headers, window moldings, flashing, weeps, and perhaps accents, all of which will contribute to the work you will need to do. It is easy to understand how this material selection can affect how much of your fees you will be required to use to document the project.

In the case of both percentage and square footage-based fees, you are particularly vulnerable during construction. If the schedule runs long, even if it is in no way your fault, you are still providing services, longer than planned. Some architects may try to spell out the exact amount of time their fees will cover during construction (say, in numbers of months) in an effort to minimize potential risk, but what if the project encounters challenges during construction and the owner or contractor identifies your work as one of the reasons for delays? Going back to your clients at this stage in the project, especially if there are conflicts of any kind, for additional compensation, may not be practical or advisable. It is often hard to make a case to the client for why you need an increase in fees if the project hasn’t changed, especially if the contractor in any way claims it is your complicated or unusual design that is creating scheduling issues.

Based on our experience, in an ideal world all residential projects would be designed, documented, and administered through construction using hourly fees for architectural services. Unfortunately, hourly fees are often a hard sell with clients. Many clients simply will not agree to what they perceive to be an open-ended contract for professional services. No matter how well you explain what you are doing for them and how you plan to deliver your services, hourly contracts imply a lack of discipline.

As mentioned earlier, clients will naturally feel the fees you are charging, no matter how reasonable, will be higher than they want to pay. This is particularly true with regard to hourly fees and the way they can appear to not have a cap. Our experience has been that for our clients who do agree to hourly contracts for professional services, do experience a point of fatigue where the always varying costs reflected in our monthly invoices seem to affect their perception of the quality and value of the work we are doing.

With hourly fees you have the potential to make a profit on every hour invoiced to the project. The fee you charge per hour for yourself and the rest of your staff working on the project will be an amount that includes an appropriate portion of the persons’ overhead cost and a profitable return on these costs.

Professionally we see the advantage of hourly fees in the way we can deliver services. The greatest single advantage to hourly fees is the ability for you to fully explore the possibilities of the project to arrive at an optimal solution. For you as the architect, to have a vehicle to be compensated for all the time it takes you to fully explore the project and the best way to build it, hourly fees are truly optimal. Even if you are able to explain the value this provides to the clients, it is often unacceptable to them.

So how do you get hourly fees and still provide the client with some form of limit or control of their exposure? We suggest a hybrid fee structure that we think distributes risk fairly to all and ensures the architect is compensated in a logical manner.

First, provide services hourly during design (and design development). This gives the client(s) the incentive to move quickly and efficiently when making design decisions or allows the flexibility to ask you to explore more options or directions if they are engaged or excited by some possibilities.

During this (design) phase try to define and obtain approvals for as many of the overall elements of the project as possible:

• The floor plan and the site plan

• Exterior fenestration and joint patterns, major site feature parameters (placement of pools and walks if they are a part of your contract)

• Key heights and elevations of floor, roofs, and major structural elements

• Finishes

• Layouts and cabinet configurations for the kitchen and bathrooms and other high program areas

Draw it all and get the clients to sign off on it before you move on to construction documents.

Second, provide services required for the construction documents on a prenegotiated fixed fee per square foot. This suggests that once the design of the house is fully realized and the overall size is agreed to by the clients, you can move to a fixed fee. Prior to this point the design work should include adequate design documentation to initiate detailing and the work of consultants. As the house is now finalized, this size can be safely assumed to have the agreement and approval of the architect and owner. Calculating the fee is now simply a matter of multiplying the total area of the house by the agreed fee per square foot.

If the project changes or there are owner-initiated additions to the scope during construction documents, then you can go back to charging hourly while you make the revisions.

It might be reasonable to consider calculating the final fee for the construction documents phase of the project by using two different numbers: one fee number for air-conditioned area versus a lower fee number for area under the roof. Air-conditioned area would reflect the interior area of the house subject to heating and cooling (climate control). Area under the roof, but not air-conditioned area, would be garages, covered porches, trellis structures, outdoor dining areas, etc. Generally the fees for the area under the roof would be lower than the fees for the air-conditioned area. Not including some form of compensation for these parts of the project can open you to extensive work designing and documenting these spaces without adequate compensation. The residential real estate industry has created an artificial value for houses by defining them based on their cost per square foot of air-conditioned area. Exterior spaces, no matter how elaborately designed, typically are not included within the calculated square footage of the house, which is one of the reasons exterior spaces are so unreasonably small in merchant-built housing.

Encourage your clients to allow you to negotiate your consultant fees after design is completed. With the design in hand, you will have a clear understanding of the scope of work; and if you have to get multiple proposals from your potential consultants, they are working from design drawings, not just verbal descriptions. Once the proposals have been received, you can allow the clients to be part of the review and selection process. It can also potentially provide an opportunity for the client to meet and evaluate the consultants and their proposals so the clients will more fully understand the value consultants will bring to the project.

Once the construction documents are completed, return to providing services hourly during the pricing process while you are bidding or negotiating with contractors. If the pricing process goes quickly, the fees charged to the client are minimal. But if the pricing process gets complicated and you are required to be actively engaged in the process, you are adequately compensated. This is particularly true in the case of extensive value engineering where you will be actively engaged in helping the contractor develop alternatives while keeping the design as intact as possible.

It is relatively easy to help the client understand that during bidding or negotiation, the amount of time spent helping the contractor(s) will result in a more thorough understanding of the project and a better qualified price.

As the lead professional working with your clients during the design process, you will build a relationship of trust with them. You and the members of your firm, perhaps some of your consultants, will be the only design and construction industry professionals whom they will know until you begin to price the project and the contractor enters the scene. If the pricing for the house is over budget, how do you handle your relationship with them? When the price becomes available, if they are disappointed, how you address the situation will affect the whole process and outcome going forward. Potentially this is a hard situation for you to find yourself in if you have not kept the budget in the forefront of discussions during the design process.

If your clients are disappointed and unhappy, you have to be honest with yourself in order to determine how you will support them at this point in the project. If you are sure you have done all you could to keep discussions of the budget a focus of the design process, then your clients will be more likely to view you as part of the potential solution. Often factors outside your experience or control, such as unexpected cost increases in materials or labor, are the reason behind the higher costs. If you can illustrate and explain this, then you can probably get the support of your clients to help pay for your time spent participating in the value engineering process.

If you have not been forthright in keeping the budget updated as a part of the process, this is may be a good time to be a team player, helpful in finding budget solutions, regardless of potential compensation. Regardless of whether the clients seem attentive to increases in cost or scope during the design process and even if they have ample resources to pay for the design you have developed for them, they may still feel poorly served by your efforts. If there is a significant budget difference and you don’t appear to be part of the solution, you can risk losing their faith and trust at the critical time when the project is ready to start construction.

If you are viewed by your clients as not being a good steward of their resources, the contractor is often ready to take your place, and the results can be disastrous for you and your design. Rarely will the contractors fully appreciate the nuances and subtleties of your design. They were not part of the process and don’t fully comprehend how the project got to this place. Worse, their possible budget solutions will be presented to the owner as a way to keep the project moving forward, no matter how unreasonable. Your credibility has been compromised by the cost of the project exceeding the budget, and you will have to rebuild it slowly by supporting the client fully at this time. Now may be is the time for you to forgo short-term compensation and provide leadership to do the work required to keep the owner fully informed about the contractor’s suggestions and their ramifications for the project. By keeping your seat at the table, your active and creative participation will go a long way toward making the clients feel you are supporting them to get their project built.

The house being significantly over budget can also have a long-term affect on your professional reputation. Regardless of your side of the story or the success of the final project, if the clients feel you did not watch out for them financially, they can make a lousy or at best unenthusiastic reference. Value engineering is best considered a part of your design efforts as you strive to keep the design intact at a cost the clients can afford and feel some level of comfort accepting.

It is virtually impossible to accurately project the fees you will need to properly support the project during construction at the time you and your client are coming to an agreement for your services. The number of variables should suggest to you and your client the advantages of invoicing hourly for your services during this period of the project. At the time you are coming to an agreement, you cannot be sure how long the project will take to construct, who the contractor will be, and how much the client will want to make revisions or additions to the scope during the construction of the house itself. It will work best for the project if you intend to provide services hourly during construction administration; this works very well and is fair to the clients.

Invoicing hourly accommodates the ebb and flow of the construction process. At some periods you are required to be actively involved on-site and in the checking of submittals and shop drawings. At other times you are rarely needed at all. Your total involvement is also dependent on the contractor selected to do the work and her or his ability to interpret and execute from your drawings.

If the clients want to make revisions in the field as the project is going up, with hourly compensation you are already set up to provide the services as needed. Invoicing hourly allows you to meet their needs in a complete and competent manner, without asking for additional services.

If the clients ask you to meet or be involved with other vendors and subcontractors (audio visual, entertainment, security, landscape, or hardscape), you have a vehicle for compensation in place.

Your clients may need your help to support their efforts in obtaining finance for the construction of the house you have designed for them. This is outside the normal experience and expertise of many architects. However, you will be uniquely placed to provide assistance through your understanding of the house itself and the way it will be constructed. You will understand better than anyone else the unique features and qualities that will make it a special and desirable place to live.

How do you deal with issues that come up for the owner during financing? What if the house is unusual enough to be a problem for a lending institution due to lack of comparable properties available for appraisals? On several occasions we have found ourselves helping our clients convince their lenders that their houses are acceptable risks for financing, not because of the client’s financial situation, but because the house cannot be easily categorized to attempt to appraise its value.

It has been our experience that this is most often an issue with architect-designed single-family houses, particularly in neighborhoods or communities without a tradition of architect-designed houses. Upscale “custom communities” and rural areas are often places where these issues arise. In custom communities or even developer subdivisions, houses are typically valued and financed on the criteria of cost per square foot and amenities then perceived as typical of the marketplace. Most of these developments tend to group houses by size, similar quality of construction, selection of materials, and amenities. The costs for the houses within the development fall within a fairly even set of parameters when they are first constructed. Subsequent increases in their value can be characterized as following a similar pattern.

When clients commission an architect to design a house, they usually expect a certain level of care and quality to be integrated into the design, often at a premium over the cost for typical developer-built houses. The overall size, expressed as square footage, is only one component of the overall design. An architect will usually organize the structure and foundation carefully, selecting materials for durability as well as visual appearance. Typical amenities found in developer houses will not always make their way into an architect’s design, simply because the priorities are different. Finally, there is the very real possibility that the architect-designed house will not be stylistically compatible with the other houses in the neighborhood. It may even be characterized as contemporary, and it is likely there will not be other houses of that level of quality or careful detailing available to compare it to.

When the owners find out the lender is having trouble processing their loans, they will naturally call on you for help. You as the architect are often the arbiter and guide for the owner and the lender in these situations. The owner is particularly dependent on you to help make the case for why the house is so “expensive” or “unusual” compared to others. It may require you to meet with the lender or the appraiser, to explain the house in detail, focusing on the way it will be constructed and the relative quality compared to other houses.

For you to assist them fully, you will often be required to spend a lot of time providing professional services in undefined areas to help them with their lenders and not put them in the position of being required to sacrifice some aspects of the design to bring it into compliance with more typical properties. If the owner is particularly pressured during this period, again it is in your best interest to help in every way possible without your compensation being in the forefront of your efforts. Sometimes the lenders will suggest simply modifying the design, indicative of a lack of understanding of the process you and the client have been through to arrive at the house they are trying to build. It is often easy for the lender to observe your reluctance to make changes in your design as you are not being supportive of your clients, again a misunderstanding of the services you provide.

Over the last several years we have come to understand that lenders are very different in their appreciation of what an architect can bring to the project and the unique qualities of the houses. When we witness stronger efforts on the part of some lenders to support clients who want to build these houses, we try to keep these lenders in mind for referral to our other clients who experience problems with financing. It is providing ultimate value to your clients when you can introduce them to lenders who will enthusiastically support their effort to build an architect-designed house.

In the architectural profession it is typical to refer to other architects as your peers. What they really represent is your competition. In most cities there will be a group of architects who specialize in residential design, and in some combination they will often be interviewed by potential clients considering identifying an architect to design their new house. Additionally there will be other architects who don’t typically design houses but who may be considered for one reason or another, and finally there will be those who will design a house on the side from their regular work. Each of these possible service providers will arrive at the fee for his or her services differently. Comparing and contrasting them to your fees will be something you will have to consider.

When you are developing a fee proposal for a potential client, it is helpful to remember you are often at the mercy of your least informed (or dumbest) competitor. In reading this book you are being given a clear understanding that the design of houses has to be considered within a business context in order to be a rewarding and ongoing part of your professional practice. For you to practice in a manner that allows you to meet your client’s expectations, you have to be able to obtain fees that will support your efforts and allow you to focus on the project. Simply put, you have to be able to justify the fees you plan to charge and be able to explain them fully to your client.

If you want to begin to design houses and don’t have a house in your portfolio, you may feel you have to take one at a potentially low fee to make your firm attractive to a client as a possible architect. That is a business decision you have to make, but as was suggested before, you will be more successful making this transition to single-family residential design if you have a client who is already familiar with your services. This type of client would allow you the opportunity to do a residential project within the context of an ongoing professional relationship. The idea of taking on the commission for a house as a “loss leader” doesn’t fully consider the schedule for delivery of professional services as long as 24 months (potentially even longer). A loss leader over that period of time can have far-reaching business consequences for your practice.

Houses are often “first jobs” for new practices, and many become that very loss leader that gets a firm started. This is perhaps a bad strategy, but it is a strategy that exists and can be a factor that drives how you will be able to set and negotiate your fees.

At some point you have to try to negotiate the fees you intend to charge as a standalone discussion with your potential clients, without consideration of what other architects are charging for their fees. This does not suggest you can ignore the competitive landscape, but you should be able to define clearly what you do for your fees, what your experience is in terms of the time it takes to execute the project and what possible issues can arise that you need to be prepared for. The fee discussion should really be a dialogue between you and your clients with the goal of your educating them on the design and construction process and what you will be doing. Their part of this dialogue would include them telling you their expectations. If you both listen carefully, you should be able to come to a consensus as to what service they need and what you can expect to receive in compensation.

The fact that you are discussing fees in detail suggests that the potential clients are inclined to find a way to work with you. If how you establish fees is discussed in your first meeting and you never meet again, either they were scared off by the potential amount of your fees or they didn’t feel comfortable with your firm or your portfolio. But if you have a second meeting, you can be reasonably certain they are at least considering you for their architect.

It is also reasonable to ask the potential clients what other firms they are considering. It is useful to know if the other firms are similar in size and practice to yours or whether the clients are considering a start-up firm or a moonlighting professional. You should be able to clearly explain the difference between your firm and the services you can provide compared to other firms, even individuals doing the job on the side. But if the clients’ only criterion is to get the low-cost provider to design their house, as disappointing as it may be to lose the job, it is probably best you don’t get the commission.

Once you have negotiated an agreement for the fee and the scope of the project, you need to create a written proposal that can be used as a contract or the basis for a contract. It has been our experience that the AIA Standard Form of Agreement for Architectural Services is a difficult and daunting vehicle for you to present to a client as the contract for your services. Even though it is the industry standard and we use an AIA Standard Form of Agreement for most of our commercial and institutional work, we try to avoid it when contracting with clients for the design of a single-family home.

That said, if you feel you need to utilize an AIA Standard Form of Agreement, there is an existing agreement tailored to residential and small commercial projects that is quite good for use with your clients. It is the AIA B 105, Standard Form of Agreement Between Owner and Architect for a Residential or Small Commercial Project. It does not fully allow for the description of the scope of work in the manner we find most straightforward and inclusive for working with nonprofessional clients (clients who do not usually contract for architectural services). But considering the other AIA Forms of Agreement available, we think it is the best.

We have developed a proposal format that works well for our firm and is reproduced below. In our experience about one-half of the time our clients will have their attorneys review and modify the proposal format, but we have yet to have any clients require us to use another form of agreement or create one of their own for the specific project. We have added additional language to satisfy some attorneys and further defined the breaks between tasks and services or the authorization to move from one type of compensation to another, but overall it has been acceptable to them and proved very serviceable for our purposes.

Below is a sample proposal agreement for architectural services that incorporates the items discussed above in the format we use when contracting for services with our clients. It is placed here as an example, but for the last 13 years it has been the basis for all our residential projects and with various modifications for specific clients and projects has been a useful tool.

Thank you for allowing (your firm’s name here) Architects the opportunity to provide this proposal for architectural services for your new home. We are excited about the opportunity this project represents and look forward to assisting you. This proposal includes a description of our proposed services and fees, developed based on our conversations and the meeting(s) with you to define the proposed scope of the project. After your review of this proposal, please call me and we can go through the points carefully, discuss them in detail, and revise the proposal where necessary to accommodate your specific needs or concerns.

_______________ (name/names of clients) intend to demolish an existing house and build a new house, the _________________ (name/names of clients) House, on the lot. The scope of work would be for the design of the new house, including terraces, patios, porches, pools and outdoor hardscape, coordination with the ________________ (name/names of clients here) and their consultants (if any), reflecting the ideas and vision of the ________________ (name/names of clients). The proposed house size is approximately ________ (lower range size) to _______ (upper range size) square feet of air-conditioned space and a ____ (number of parking spaces) car garage. The scope of work would be for the new house and related exterior (outdoor) construction.

The proposed budget for the house is ______________ (insert budget at time of contract here). This is the cost for the house and related structures only and does not include landscape, hardscape, pools, water features, furniture, or low-voltage wiring and equipment (security, audio/visual and related infrastructure, cable or satellite television, phone, and data).

Discussed below is the proposal and possible work scope for the architectural design.

________________ (your firm’s name) Architects will develop with the ________________ (name/names of clients) design concepts and ideas for the new house. ________________ (your firm’s name) will design and document concepts based on direction and ideas expressed to us by the _______________ (name/names of clients). The information provided to ________________ (your firm’s name) Architects might include, but not be limited to

• Identification of rooms and spaces to be included in the design

• Desired materials and finishes for use in the design and construction of the house

• Size, scope, and function of the possible rooms and spaces

• Patterns for use in the new house

• Outdoor amenities to be included in the design

Using this material and in conjunction with direction from the ________________ (name/names of clients) and their consultants, ________________ (your firm’s name) Architects will develop concepts for the design of the house including but not limited to

• Site plans

• Floor plans

• Elevations

• Building sections

• Interior elevations of major rooms and spaces

• Initial finish selections and building materials selections

These ideas will be presented in drawing form at meetings at the (name/names of clients) home or at the offices of ________________ (your firm’s name) Architects or at alternate locations selected by the (name/names of clients). ________________ (your firm’s name) Architects will travel to locations as required by the ________________ (name/names of clients) for meetings. At each meeting new concepts will be presented and reviewed for revision and refinement in subsequent meetings. _________________ (your firm’s name) Architects will develop an agenda of issues to be resolved at the meetings and will document approvals and areas of discussion so that the ________________ (name/names of clients) and ________________ (your firm’s name) Architects teams move forward in an efficient manner but also one that allows for spontaneous development and the incorporation of new ideas as the project develops.

________________ (your firm’s name) Architects prefers to have regularly scheduled meetings between the client and the design team so that work is focused on addressing design concerns and issues as they arise and to develop and foster consensus. Ideally we would plan to meet at least once every two weeks if your schedule allows.

At the end of the design phase, the team will agree that the design for the proposed house is complete and ready for detailed development and documentation.

Once the design is approved by the (name/names of clients), ________________ (your firm’s name) Architects will proceed with the development of Construction Documents for the new house. Construction Documents are the detailed drawings that will be used for obtaining a building permit, obtaining approvals, pricing the project by a contractor, and construction of the house.

Before ________________ (your firm’s name) Architects can begin the Construction Documents, we will need the following items from the ________________ (name/names of clients):

1. Meets and Bounds Survey of the site including utilities, easements, and setbacks and a legal description

2. Soils report from a soils engineer

If the ________________ (name/names of clients) don’t have access to these, _______________ (your firm’s name) Architects can arrange for them to be made by consultants we work with often. With these two items provided we can begin the Construction Documents. Construction Documents will include, but not be limited to

• Plans

• Ceiling plans and lighting layout and design

• Elevations and building cross sections

• Wall sections and details

• Door and Window schedules and details

• Finish selections and details

• Millwork (cabinet) design and details

The intent is for the project to move into Construction Documents without significant revisions or changes to the design or deviations from the approved scope of work. If ________________ (name/names of clients) initiate significant changes or additions to the project that require ________________ (your firm’s name) Architects to stop work on the Construction Documents and then make revisions to accommodate the design changes, then this work will be revised at an hourly rate as described in the Fees and Terms portion of this proposal. Once approval is obtained from ________________ (name/names of client), the architect will resume work on the Construction Documents.

When the Construction Documents are complete, ________________ (your firm’s name) Architects will review these with the ________________ (name/names of clients) for completeness and compliance with the design intent. After this review ________________ (your firm’s name) Architects will make required revisions to complete the set of drawings.

As required and at appropriate milestones in the process, ________________ (your firm’s name) Architects will engage consultants for the Structural Engineering and for the Mechanical, Electrical, and Plumbing (MEP) design for the new house. These drawings will define the structure of the house including the foundation and the air-conditioning, plumbing and electrical portion of the new house’s design.

When the Construction Documents are complete, ________________ (your firm’s name) Architects will issue them to one or more general contractors for pricing in a manner approved by the ________________ (name/names of clients). The drawings can be issued for competitive bid to multiple contractors or for a negotiated bid with one contractor. This method of pricing the project can be determined at the time the project Construction Documents are completed.

When pricing becomes available, ________________ (your firm’s name) Architects will review these costs with the ________________ (name/names of clients) and make reasonable revisions as required to bring the project into conformance with the project budget.

________________ (your firm’s name) Architects will issue sets of drawings for permit review to the selected General Contractor and will revise the drawings to reflect any comments from the permit review process.

During construction, _________________ (your firm’s name) Architects will attend all on-site construction meetings, communicate with the contractor to assist with questions that arise, review all pay requests and change orders. Additionally ________________ (your firm’s name) Architects will inspect the project to ensure compliance with the intent of the contract documents.

________________ (your firm’s name) Architects will review all shop drawings and submittals for compliance with design intent and the Contract Documents.

At the completion of the project, ________________ (your firm’s name) Architects will make a punch list of nonconforming or incomplete work and communicate this list to the contractor for revision and completion as required.

________________ (your firm’s name) Architects will perform the above referenced services for the house for the following fees:

Design: Hourly to the approval of the design by the ________________ (name/names of clients) of the layout and design concept.

Construction Documents: Fixed fee based on the final scope of work and the square footage of the areas affected. This includes the following components:

1. New house: __________ (lower range here) to __________ (upper range here) air-conditioned square feet

2. Outdoor living areas, terraces, and patios (to be verified in design phase)

3. Garage: __________ (number of cars), _________ (assumed size based on 200 square feet per number of vehicles) square feet.

For purposes of this proposal,

1. $__________ (enter per-square-foot fee cost here) per square foot × final interior air-conditioned square footage.

2. $__________ (enter per-square-foot fee cost here) per square foot × final area under roof that is occupied (garages, patios, screened porches, cabanas, etc.)

Bidding, permitting, and construction administration: This is the work required to support the pricing of the project by one or more contractors and during construction to monitor the contractor, answer questions, and provide additional direction (as needed). These services will be performed hourly as required by the ________________ (name/names of clients) and as required to support the contractor.

Design: |

$______ |

Construction documents: |

$______ |

Consultant fees: |

$______ (to be determined when design is complete) |

Construction administration: |

$______ |

Totals estimated: |

$______ (excluding reimbursable expenses) |

An outline of ________________ (your firm’s name) Architects’ hourly rates is attached to this proposal.

In addition to the fees outlined above, ________________ (your firm’s name) Architects will invoice the _________________ (name/names of clients) for reasonable reimbursable expenses. These include but are not limited to

• Blueprinting and reproduction

• Long-distance telephone and fax

• Postage and overnight delivery

• Project record photography

• Travel and lodging (if required)

For a project of this nature the primary architectural reimbursable expenses are for plotting of the computer-generated drawings, large-format copies (commonly described as blueprints), printing, and reproduction. ________________ (your firm’s name) Architects will invoice reimbursable expenses at their direct cost plus a(n) __________ percent (%) administrative multiplier. ________________ (your firm’s name) Architects will provide receipts and invoices for all reimbursable expenses with each invoice.

Fees will be invoiced monthly to reflect the percentage of completion of the work for the proceeding thirty (30) days. All invoices are due net twenty-five (25) days from the date of invoice.

Based on the discussion and feedback we have had in the meetings to date, we propose the following schedule for delivery of our services from the initiation of design to the start of construction:

Design: |

75 to 90 days |

Construction Documents: |

45 to 60 days |

Bidding and Negotiations: |

30 days |

Total to start of construction: |

150 to 180 days |

This schedule assumes a regularly scheduled set of meetings (twice a month) at which the team would meet and the ________________ (name/names of clients) would review and approve the work completed or provide clear direction for suggested revisions. We believe that the schedule could be compressed if required, but we would need the support of the ________________ (name/names of the clients) and an understanding of how the approval process would be expedited to provide a shorter schedule.

The ______________ (name of state where design professional has licensure) Board of Architectural Examiners has jurisdiction over complaints regarding the professional practices of persons registered as architects in ________________ (name of your state).

The Board’s current mailing address and telephone number are as follows:

________________ (Name of state) Board of Architectural Examiners

________________ (Street address and suite of state board)

________________ (City, state, and Zip code or state board)

Phone: __________ (Phone number of state licensing agency here)

We hope this proposal meets with your approval. We hope to be selected to assist you with the design of your new house. We are prepared to start immediately upon signing and look forward to the successful completion of the project.

If you wish to engage ________________ (your firm’s name) Architects in the professional services described in this proposal and required for your new home and have no revisions to the proposal, please indicate by signing below. Retain one copy for your records and return the other to ________________ (your firm’s name) Architects. Thank you for your consideration and warmest regards,

(Your firm principal name here) |

Date |

(Name/names of clients here) |

Date |

The house I designed in Dallas, Texas, for Paul and Carla Bass was my first ground-up (all new construction) house and an important moment in my career and professional development. Besides starting my residential practice in earnest, it provided the opportunity to learn how to work with a client for the design of a house after 16 years doing commercial design. As clients, Paul and Carla had a level of enthusiasm and courtesy in their manner of working with me that enhanced my excitement at obtaining this commission for their house. Their happiness with my work and the design and construction process helped me through the inevitable problems that arose during the pricing and construction. I have since had the opportunity to design a number of houses for a broad variety of clients, but none would have been as perfect as Paul and Carla for my first house, or as instrumental in helping me to secure additional commissions in the future.

The Bass’ were empty nesters, and downsizing from a larger family house was an important consideration in the process of designing this house. The Bass House is small by the standards of most of the houses I have designed since, only 2500 ft2 air-conditioned, but it has a full program of interior spaces and the Bass’ had specific existing furniture groupings that needed to be accommodated in the design. The programming process included listing specific furniture, art, and rugs to be planned for in the new house. While it was not an extensive list, it did dictate certain spaces that had to be present in the house and the need for formal and informal living and dining areas, negating the opportunity for the house to have larger spaces through a shared set of program activities (we could not plan a single large great room for all the hospitality and living functions).

The site was small and awkward with a diagonal property line that, when taken in conjunction with the required setbacks, left a relatively small building area within which to plan the house. Added to this constraint were program requirements for an outdoor pool and covered exterior porch for sitting and dining and a two-car garage. Quickly the planning of the house on its compact site became an academic exercise in tight spatial organization.

The house was located in a small town, almost entirely residential, surrounded by the city of Dallas with an exceptional public school system that contributed significantly to the very high property values. Originally a neighborhood built to provide housing for educators and staff at Southern Methodist University, it was considered at the time of its founding to be so far north of downtown Dallas that it had to incorporate as a separate city to provide education and services to its residents. Initially the town was developed with a variety of house sizes, but subsequent changes in the quality of the schools in the surrounding communities made the school system the neighborhoods’ primary draw. The by-product was an escalation in property values which had the effect of making the neighborhood accessible only to the very affluent. House lots as potential building sites became more valuable than the houses on them, and the result was a pattern of knocking down older houses and building new ones on the then-empty lots. This coincided with the newer residents’ desires for larger houses with updated amenities, which in turn led to a wave of demolition and new construction of larger, more expensive houses on the lots. This factor of upsizing over the previous houses had contributed to dramatic change in scale of the fabric of the community with smaller, older houses sitting side by side with larger, taller houses that filled the available building footprint. The street on which the Bass House was located was in transition; older, relatively small homes were being knocked down and replaced with much larger houses. The older houses not only were usually small in square footage, but also had a pleasant diminutive scale in terms of floor-to-floor heights and details. These houses had been built by developers, for the most part in the 1920s, so they greatly varied in their material pallets and fenestration patterns, making every house truly unique. The newer houses which replaced them could be derisively characterized as McMansions, all sharing a clumsy sense of scale and proportion, awkwardly sited and clumsy in regard to details. Additionally, almost all the new houses were clad in heavy red brick with vaguely Georgian details and trim, with the result being houses that were large, dark and imposing, whereas the older houses tended to be softer beige or tan masonry or stone which visually receded into their sites.

Fortunately all the houses held a single street setback line and faced wide sidewalks that knit the entire neighborhood together. The trees planted when the original houses were new in the 1920s had been growing for 70 to 80 years, so even the new houses were set in shaded yards and partially obscured by foliage. Our site had one large tree, a pecan, which we took along with the setbacks as the main constraints to placing the house on the lot. Setting the building front façade square to the street at the common setback line became one of the first decisions I made at the start of design. I also wanted to have all the public spaces open visually to the street, the kitchen and den open to the backyard and pool, and the garage at the back of the site with direct vehicular access to the alley which ran parallel to the street and defined the rear property line.

Designed for a mature couple, the house is one level except for two small guest rooms located above the attached garage. The Bass’ wanted to be able to entertain several guests comfortably so the living room, dining room, den, and kitchen all form a loop that circulates freely through the house. The master suite is set off to one side.

The house was planned on a rigorous 4 ft × 4 ft grid, which was actually scored into the exposed concrete floor. Interior and exterior walls are aligned with the grid, which is expanded on as the primary decorative device for the cabinets, and other interior features such as door openings relate to it too. This same grid became the organizing device for the exterior elevations and the building cross section. The small scale of the house keeps this grid from becoming aggressive or compulsive. The gird was further subdivided into 24- and 12-in modules for planning purposes, particularly on the façades where the windows are 24 in tall × 48 in wide units stacked horizontally (Fig. 2.1).

To make the small rooms feel larger, the ceilings are all 12 ft high and in part of the house follow the roof slope, filling the volume of the cross section. Tall windows go all the way to the underside of the ceilings, bringing light into the upper part of every room (Fig. 2.2). Both these decisions, made early in the design, contribute to the feeling of openness almost all first-time visitors comment on. The house literally opens up in all directions (Fig. 2.3).

The kitchen is large enough to allow for a table to be placed in its center. It is a U-shaped layout with the open end completing the den, literally making them one large space. All the cabinets are white plastic laminate, and the appliances are stainless steel. A door connects the kitchen with the adjacent formal dining room, designed as a perfect square with a round table at its center. The owner’s chandelier was a preexisting piece which along with the table had to be considered in the design (Fig. 2.4).

FIGURE 2.1 Floor plan of the Bass house shows its compact organization and clearly articulated circulation. The rooms to the front of the house flow through one another to the rooms in the back which all open to the pool. (Drawing by Zachary Martin-Schoch.)

The house was also to be economical so finishes, though straightforward and simple, are carefully detailed and executed. Exterior walls are white painted stucco, and the roof is prefinished standing seam metal in a pale gray. The floors are all stained concrete with a waxed finish, even in bathrooms. All the interior walls are painted gypsum board. Exterior windows and doors are clear finished aluminum storefront as are the interior door frames. All the millwork and interior doors are clad in white laminate as are countertops. Bathroom walls and shower enclosures are tiled in off-the-shelf 12-in × 12-in white marble.

Because the long side of the house faces north and south, we were able to design for careful solar control and avoid heat gain through the windows. The front windows face the street, and the rear windows face south to the pool area. These windows are shielded by the covered outdoor porch on the rear of the house. The windows never have to have shades drawn due to excessive direct sunlight coming into the house, only to provide privacy, the result being a house that is full of natural light, but not heat or glare.

FIGURE 2.2 Street view of the Bass House with its large north facing windows and simple stucco volume. (Greg Blomberg Photography.)

FIGURE 2.3 Interior of the Bass house looking from the entry foyer into the den. All the spaces are open filled with natural light from the large windows of the north and south elevations. (Greg Blomberg Photography.)

FIGURE 2.4 The kitchen of the Bass house is open to the den and its two informal seating areas, one for television viewing and one centered on the fireplace. (Greg Blomberg Photography.)

The standing seam roof has a simple hipped shape that overhangs the exterior walls by 2 ft on all sides. In lieu of gutters and downspouts, there is a concrete apron around the house that acts as a continuous splash block, diverting rain runoff into a gravel surface drain that is part of the landscape design. The decision to use a prefinished metal roof was similar to the choices for all the exterior materials in that it required minimal maintenance. All the roof eaves are also clad in prefinished metal panels, leaving no exposed wood trim to be painted. The roof, along with the aluminum windows and doors, and the concrete paving and walks left only the stucco as something requiring periodic repainting (Fig. 2.5).

The landscape design is crisp and contemporary, reflective of the design of the house. The small rear yard with the pool is particularly handsome. A small runnel with shallow fountain connects the pool itself to a landscaped side yard. The rear covered porch is continuous along the back of the house and provides a shaded place to look at the pool. Glazed doors from the den and master suite open onto this porch, which is deep enough to be comfortably furnished with a seating area and a dining area.

FIGURE 2.5 View of the poolside elevation of the Bass house showing the large dormer windows and covered back porch. The windows in the den open directly to the pool. (Greg Blomberg Photography.)

At the time of this writing the house is now 12 years old and has been impeccably maintained by the owners. The first repaint of the exterior was done last year so the house is a sparkling white again. The landscape has matured to fully integrate and settle the house into the site. The owners became and have remained close friends and allow me to bring potential clients through the house anytime on very short notice. This project remains for me one of the most satisfying of my career.