The process of bidding and negotiating with contractors is an important part of the construction process and is critical to the success of executing the work and building the house you have designed for your client. Although it can seem like a mere administrative step in getting the project underway, it actually has an important role in first defining the cost of the project and then establishing how the contractors understand the project before they begin to build it. This activity often determines whether the project is a success as it bears directly on cost and ultimately on the quality of the project’s execution. It is important to understand the direct relationship between the way a project is priced, leading to the selection of a contractor, and the context in which the contract for construction will be created.

Bidding and construction of a carefully designed and well-detailed house take a considerable amount of time and require the patience of your client to be completed properly. How much time is dependent on the size, scope, and complexity of the project, but even under optimum circumstances and with a fairly straightforward design, it is a potentially lengthy process when undertaken correctly. With the pricing of the project starting after what your clients may perceive (with some justification) as a protracted design process, the clients are usually beginning to become anxious for the project to move from a conceptual state to a realized form, and knowing how much it is going to cost becomes a major preoccupation in their lives and for their relationship with you. The architect must balance the clients’ motivation for expediency, the need to know a number, while keeping control of the pricing process which is critical to the ultimate success of the construction effort. In this chapter we present the project’s bidding for construction as a process, one that the architect has a significant role in facilitating for the project to be built in a correct and timely manner. In this phase of the project, you and the owner take the idea of the house that you have been creating and documenting together and hand it over to a contractor to price, subject to all the human foibles of any activity involving a lot of people.

On the bidding side, you and your clients have to be prepared to provide the contractor or contractors with adequate time to thoroughly understand the project and coordinate their pricing efforts. To make this possible, you have to provide the contractor with all the information necessary to make a complete bid. Finally when you have the bid in hand, you have to allow yourself enough time to review it carefully for completeness and to resolve any ambiguities, before reviewing it with your clients.

Once potential clients indicate they want to work with you, most architects immediately begin the process of getting an agreement for services or a contract in place. This is natural considering your need to begin invoicing for your professional time spent with the client as quickly as possible; after all, as professionals that’s what we do, sell time for payment. Recently I began to spend a considerable amount of time working with my residential clients on the front end of my relationship with them, before I even had a contract in place. I use this period of initially consulting with them as a time for setting expectations before we have even started design, by taking time to define the project in verbal terms, not drawings, as a way to understand expectations for the size of the project, materials, and finishes. Further, we augment our assumptions with discussion of pricing and budgets, usually bringing in one or more contractors to talk conceptually about pricing and having them create outline costs based on their previous experience. Putting those numbers out into discussion has proved to be a solid way to verify the clients’ comfort with the cost of the project before we ever begin to design it. It takes a lot of time to do this right, sometimes even several weeks, but it allows you to have “expert input” from construction professionals to give the client an idea of what to expect the project to cost. In my experience when I do this at the beginning, before I have a contract and before I’ve started to design, I have been able to begin the design process without the distraction of not really knowing how much the house will cost. This is particularly true of remodels and additions. Creating a relationship in this way indicates your willingness to put the clients first and is a way to develop trust and goodwill before they begin to actually evaluate your design efforts.

This approach does not make sense in any strictly business evaluation. You are using your expertise to define the project for potential clients who are then free to be disappointed with the results and abandon the project, even to go find someone else to work with. I am also aware that this runs counter to the recommended guidelines of the American Institute of Architects and the idea of providing services without compensation. But from my experience, if I spend a fair amount of time up front defining the project and getting a complete understanding of the potential cost before I start, I am more likely to get a meaningful contract signed by the owners and not have any disappointment or misunderstanding when the completed design is priced. It does entail providing what may be characterized by some as free work, and there is a risk you won’t get the job. But it also means when you do get the project, you and the clients are both sharing assumptions, which can then be used as the basis for your contract. In a practical sense, moving forward in the same direction as your clients is good when designing a house for someone who is paying you to do it.

One way to justify this effort at “soft bidding” the project in a professional sense is by pointing out examples of other project types and how you traditionally go about getting the work. If your firm regularly works on architectural projects other than houses, you will know that to compete for a commercial or institutional project often involves spending long hours generating responses to an RFP (Request for Proposal) or RFQ (Request for Qualifications). Once these are submitted, interviews and presentations are used as follow up to further qualify your firm and the team you have assembled for a project. I liken the time I spend determining a budget for the house on the front end of a residential project as much the same thing, the same use of time making the clients comfortable with our capabilities. Being aware there is no guarantee we will get the job does not excuse us from making the effort or spending the time trying to fully understand it. For me it is simply part of the cost of going after the project.

If during this soft bidding process the initial numbers provided by the contractors for the project come in over the clients’ expectations for the budget (which they always do), you have to have time to help them understand why, realize the ramifications of value engineering, and help guide them to a budget that they can live with and feel comfortable with before you begin design work. This is a good time to revise the scope of work to bring it more in line with their expectations, rather than after you have completed a set of drawings and they have paid you a significant amount in fees. Again it is an opportunity to provide value and build trust.

I have a consistent history of projects that, when priced, come in over budget, making everyone unhappy and uncomfortable when they do. No amount of careful planning or candid disclosure of your thoughts regarding the cost can prepare the clients for a project that has a price they cannot afford. Even taking reasonable precautions up front doesn’t fully insulate you from pricing overruns and changes in the cost of construction materials, but it can help your clients understand that you worked together to define the budget and had reasonable expectations it was accurate. For our projects with modest budgets I always try to design within what are typical or reasonable expectations for the materials and quality of the project. Even so, I still have problems with budgets. In part this is the nature of my practice, trying to do the maximum possible with every design opportunity, but also it is so because I just don’t have the opportunity to be fully aware of what is driving construction costs at any time.

By spending time up front I am able to define the job in a budget and programmatic sense, but far more important, I develop a working relationship with the potential clients. My experience has been that every client is different and her or his way of interacting with me varies. Some clients are comfortable with professional service relationships; they have worked extensively with lawyers or accountants and understand the idea of fees for service. Others do not. They don’t see the work we do as a service in support of a process, but more as a commodity, as in the set of plans for building the house being an end result with a price value on it. This initial soft bidding effort and the services that accompany it provide the clients with the opportunity and time to get to know me, what I can do for them, my knowledge, and how I work in a professional relationship. Likewise, it allows me to understand how well the clients can articulate their needs, whether they can understand or read drawings, and whether they have a realistic sense of what things cost, not least of all the fees we are about to charge them. Finally it provides me with a snapshot of what it will be like to work with them and how I will need to prepare for meetings and presentations. It is always time well spent.

If after our efforts on the front end we don’t get the project, we are parting with a relationship intact, due to reasonable financial expectations we can’t meet with our design for what the client can afford to spend, not because I’ve spent a lot of time and their money and disappointed them. They will remember the experience positively and therefore will remain a potential source of referrals.

Bidding the project refers to pricing the project. The word bid refers to the sum for which contractors, based on detailed estimates they have prepared, are willing to construct a building project. The scope of work of the bid can be an item as small as painting a room or as large as the construction of an entire house. Usually the word bid is associated with competitive pricing where all the bidding contractors begin with the same assumptions and based on their experience and purchasing power provide the best possible price to build the project. Even though the idea of bidding something seems to be commonly understood by many people who don’t work in the construction industry, in a practical sense very few people have experience with the bid process in their daily lives and they don’t really understand its ramifications, particularly as they pertain to the construction of a house.

The lack of experience of most people in actually bidding something is understandable. For most of us, bidding is not involved in many daily purchases. In our society we shop in retail stores where prices are clearly marked, and we make a choice based on our evaluation and need to buy it. Consumers who use professional services similar to those offered by architects (fee for services that are not a tangible product) incur fees associated with the work to be done before they begin to utilize these services. You may get multiple price quotes for a major car repair, but these prices are usually based on a preset fee for the work to be done that is related to the time and the parts required, so it is not a truly competitive bid. In activities associated with the building, construction, or remodeling of things, many people see the advantage of obtaining multiple competitive bids. For example, if you have your house repainted, often you will solicit multiple price quotes and compare them to select what you consider to be the best value. This is also true of landscaping, building fences, replacing heating and air-conditioning equipment, and roofing. Many clients of architects will expect to have the construction work you are designing for them competitively bid. Indeed, many will think that is the industry standard, and this assumption, like many you will address in the design and building of a house, requires you to address it carefully.

I prefer to use the term pricing in lieu of the term bidding a project. It is more consistent with the way the costs for residential projects are created and suggests a more hybrid approach to determining the costs for building a house. I will use the term bidding in this chapter when specifically discussing a competitive bid process among multiple contractors. I will use the term pricing to discuss the other possible ways to develop a cost for a project.

When you are determining the whole cost for a project, pricing (as opposed to bidding) also allows the inclusion of parts of the project that you don’t expect the general contractors to provide as a part of their scope of work. For example, when we are developing budgets for projects, we like to include in the cost items such as our fees and those of our consultants, landscaping, audiovisual systems and equipment, custom items such as rugs or lighting fixtures that may be purchased directly by the owner and not through the contractors. This suggests that the contractors’ price is not the whole price of the project but a component (perhaps the largest, but still just a part) of the overall project price.

The goal you should have for pricing a project, by bidding or negotiation, is to obtain for your clients the lowest qualified price. By qualified I am suggesting this price may not be the lowest bid, or the one with the shortest schedule for construction, but it should be the most complete and comprehensive and a price that reflects a full and complete understanding of the scope of work associated with building the project. On many occasions I have had wonderful experiences working with the lowest bidder on a project. Other times I have experienced firsthand why the bid was the lowest and have tried to successfully administrate the construction of a project with contractors who spend much of their time trying to overcome an incomplete bid. This is the ultimate nightmare scenario in the construction of a house, and the only way to avoid it is to judiciously and carefully qualify the pricing for the project and remember the old adage, “If it looks too good to be true, it probably is.”

The process of bidding (or pricing) the project is complex, and it is important you administer the services associated with this part of the project in an orderly and consistent manner. Too often the temptation will exist to issue the bid documents in an incomplete form or without detailed instructions as to the expectations you have for the format and content of the bids. The result will be incomplete and usually erroneous pricing.

We frequently have projects where the owners will want to price the project to get an idea of where the cost numbers will fall before we have completed our documents. Despite sharing with the clients the dangers or possible problems of this process, they will (again justifiably) encourage us to obtain a ballpark price. It has been my experience that every time we do this, the number produced through this process, for better or worse, becomes the number the client will associate as the cost of the project, no matter how incomplete or how many assumptions are made in its development. In effect, you are asking contractors to price an incomplete project, and you can be sure the final number will change as you complete your documents.

To properly bid or negotiate a price for a residential project, the architect will have to issue more than just drawings. Many residential architects have resorted to streamlining documentation for houses to the minimum required to price, permit, and construct the project; and for many architects this has proved an acceptable business practice. Often this is a reflection of the realities of an inadequate fee to accomplish the work fully, but for residential architecture to be practiced at its highest level of professionalism, thorough documentation consistent with the project, its scope, and scale is necessary. The small numbers of drawings that are typically used by the home-building industry to permit and construct a new home to some extent have been accepted as a standard level of documentation for residential projects. To provide a meaningful level of service that is representative of your design efforts, working with your clients requires a greater level of documentation than the housing industry’s norms unless you are dependent on or expecting the contractors to generate all the details of construction.

As the architect, you will determine the materials that will be issued to the contractors to bid or negotiate the project. Unless the owner has an exceptional role in this part of the process, you will provide the drawings, specifications, and Instructions to Bidders required for them to properly price the job. I can provide guidelines based on my professional experience, but only you will fully understand your design and its myriad subtleties well enough to communicate them properly. In addition to the materials listed below, it is good to step back and look at your design with the eyes of someone who did not develop it over time and for whom it is not a resolved “whole” composition in his or her mind. Try to think about the nuances of the design, the key elements and details you expect the house to express when it is built; and with this in mind, look carefully at your drawings. Does the intent come through clearly with the materials you are providing? Can reasonably informed persons fully understand your intent from the things you are giving them to price (and ultimately to build from)? If the answer to these questions is in any way ambiguous, or an outright no, then you need to provide more in the way of drawings, details, specifications, or instructions.

We all wrestle with how much documentation is enough, especially when we don’t have what we perceive as an adequate fee to fully document the project. I suggest it is we who don’t perceive we have an adequate fee because my experience has been our clients will always feel like the fee is more than they want to pay. Our clients will not know if the documentation is adequate; they will expect that your drawings and specifications to be professionally adequate to price and build the project. To answer these questions for ourselves in a satisfactory manner requires three possible paths for consideration.

First, did you design a project that was consistent with the budget and fees given to you to provide the professional services? For many of us there is a tendency to make the most of every design opportunity and to extract the most from the project in a spatial and artistic sense. In doing this, even if it is consistent with the budget expectations for the project, you may be creating additional work for yourself in terms of documentation and detailing in order for the contractors to fully understand and price the project. If you have clients who are allowing you to do this level of exploration for their project, then it is reasonable that they should provide you with the necessary compensation to document it properly. If not, then you have to evaluate the work to be done and make a decision to go beyond what is suggested by the fees to help resolve any ambiguities.

Second, you can look at your pricing materials and evaluate whether the amount of documentation will leave large gaps in the thorough explanation of the project that will require you to have significant additional input in helping the contractor understand your intent during construction. In other words, is it better to put it all down on paper in advance or to do it as the job is built? My experience has been that ambiguity leads to inadequate pricing efforts, and that during construction if the contractors feel they did not have the information to price something thoroughly, they may ask for a change order which could put you in the position of explaining the ambiguity to your clients and their incurring additional costs. Depending on your contract and the way fees are allocated for the construction administration process, you may also have to provide a great deal of unintended service just to fill in blanks in the materials the contractors are building from. It is good to remember that if you care about the outcome of the way the project is constructed, you will have to fully explain your intent, and doing it in the field under the pressure of a construction schedule and budget can be difficult and painful. If your construction administration fees are a part of your overall budget and you have gaps in your documentation, you will be using a greater percentage of the fees providing answers that might better have been documented during the construction documents phase of your work. If your fees are hourly and you have the ability to invoice for all your time spent once the construction starts, it still puts you in the moral position of evaluating whether the work you are billing your clients for is fair or should have been completed during a different phase of the work. Either way the result is the same: you will be using your time and your professional fees to provide answers to questions that arise because of inadequate documentation in other phases of the project.

Third, no matter what our fees would prudently allow us to do in terms of documentation, we need to evaluate whether we have adequate materials to properly price a project. If we don’t, we must resolve to answer the question, Do we feel a professional obligation to provide it for the success of the project? By using success in this context I am talking about the complete execution of the house we have created with our clients in a way that fully realizes the design intent and spatial qualities of the project. This is no less than our professional duty as architects when we agree to design a project for a fee for our clients, no matter how unreasonable we may feel the amount of money is. Do we see opportunities within the project and our professional obligations that require us to go beyond our fees? It is a straightforward question to ask: are other considerations in place that require us to provide additional materials to properly price the project? The answer to this question can help you to determine what materials need to be created to properly price the project.

The typical materials used for bidding and pricing a project are Instructions to Bidders, drawings, and specifications. These are time-honored materials that document the project being priced; they are industry standards in the United States and generally the minimum expected by contractors pricing the work. Each of these is created in a different way and has a different role in the pricing and construction process. It is not unusual for one or more of the three items listed above, usually the specifications and Instructions to Bidders, to be omitted in a typical residential project, but doing so can lead to problems elsewhere in the project. Below is a description and discussion of each of these items and their role in the pricing process.

Provided when you issue the drawings and other materials for pricing, the Instructions to Bidders contain much of the critical information related to the bidding process. The information in the instructions includes information regarding when the bid is due; the date, time, and place; and how the bid is to be delivered. The Instructions to Bidders will contain information such as whether the bid can be e-mailed or faxed or if a hard copy is required.

Instructions to bidders usually include the format in which you expect the bid to be provided. This could include a sample form (if necessary) for the contractor to fill out and what items you would expect to see broken out individually in the price and in what categories. For comparison reasons, sometimes you will break the project bid form into categories using the Construction Specifications Institute (CSI) format, and this format is covered in detail below. On some occasions you may want only certain categories broken out of the price so that you and your clients can fully understand the ramifications of certain design decisions. When you are evaluating a price, it is helpful to know what parts of the project (which design decisions) are the highest in cost to execute and what parts of the project demand the highest utilization of resources. Having certain items broken out by cost can help with these types of evaluations.

It is also important to indicate how you want the price to be stated in a written format when the bid or price is submitted. For example, do you and your clients want a lump sum including all the work adding up to one number, or do you want it in parts or scopes of work? We often ask for the work associated with the construction of the house to be one price, another for the contractors’ general conditions and profit, and finally a breakout of the hardscape (walks, drives, and swimming pool). With these numbers you can then add other parts of the cost of the house (as outlined above) not necessarily to be provided by the contractors and come up with a total price for the project.

If there are alternates to be priced during the pricing/bidding process, we identify them in the Instructions to Bidders. Alternates can be for added prices or for deductions, commonly described as add or deduct alternates. It is helpful to provide as full a description as possible for these alternate items for the contractors to price them completely. An example of a deduct alternate would be the cost savings of going to an all-stucco exterior finish in lieu of an all-stone exterior finish. The projected savings of the materials and labor would be the basis for the deduct alternate. An example of an add alternate would be going to hardwood wood flooring instead of carpet as a finished floor material in all or a part of the house. We itemize these add and deduct alternates in our Instructions to Bidders, number them, and ask to have them included in the bid form, listed by number.

For remodel projects or projects with remote locations, the contractors will want to visit the site, often multiple times with different subcontractors and trades, and will need to know whom to speak with to obtain access to the site. We provide this contact information and any guidelines controlling access in the Instructions to Bidders.

Finally we use this document to identify the person at our office to call with questions, clarifications or coordination items that arise during the bidding/pricing process. We clearly state who will be responding to any questions, how that person will be keeping track of the questions asked, and how we will transmit any clarifications, discovered errors, or inconsistencies to the other bidders. By having this role served by one person from your staff, clearly identified in your Instructions to Bidders, you make sure that there is a consistent message given to everyone calling with questions. With commercial and institutional projects we often try to limit the people contacting our office to the general contractors and their direct staff, to limit the calls and possible incomplete or conflicting answers. For residential projects we usually allow anyone who is pricing the project to call our office. Our experience has been subcontractors who are pricing specific areas of the work often identify questions that are important to the overall design, and we like to hear and understand them firsthand. Residential projects usually have a limited number of contractors, subcontractors, and suppliers pricing the work, and these calls do not usually prove to be an undue burden on our time.

In an earlier chapter we discussed how to determine what drawings need to be done as part of the set to fully document the house for design and construction. With these drawings now completed with the specific purpose of describing the scope of work for the contractors to price, you will issue them as a tool to achieve an accurate understanding of the house to be built.

It is important to consider that the drawings you have made illustrate the scope of work of the project, what your expectations are for its components, not how to build it. As tools in the design process for you to use in communicating your design intent to your clients, the drawings were primarily for the communication of spatial layout and design intent. Now during pricing they will literally be used by the contractors with their subcontractors and suppliers to identify the materials and quantities required to be used in building the house. After pricing when the project moves forward into construction, the drawings will be used to provide layout and dimensional tools for the contractors to actually build the house, but again not how to do the work itself.

The accuracy of the drawings at this stage in the construction process is important primarily because they are used as tools to determine the components of the house and to estimate how much material and labor will be needed to build it. Further they will have the purpose of identifying where materials and finishes will be used and your expectations for details. When used in pricing, the drawings do not have to convey each of these things precisely and often contain coordination errors which could be serious during actual construction; but they do need to fully and completely illustrate the work to be done for accurate and complete pricing. The contractors and their subcontractors and suppliers will use the drawings for quantity surveys or takeoffs. For building and construction materials, creating these estimates are literal exercises in determining the amount of each item used in the construction of the house. Used in this context, the term takeoff refers to someone (usually the contractor or an estimator) “taking” the dimensions “off” the drawings and then doing simple geometry calculations to obtain square footages of the specified materials to be used. These areas are then multiplied by the unit cost of the materials (usually on a square foot or linear foot basis) to obtain a cost for the materials. Similar formulas are used for calculating the labor required to install or fabricate the different parts of the project. To do this work, the person doing the estimate will usually rely on the scale drawings and not on the dimensions themselves.

When building the house, the contractors will fabricate on-site, or cause to be built, certain elements that will be made up as unique products of labor and materials specific to the site. These elements are things such as the foundation, concrete work, paving and walks, framing (wood or steel or a combination), the plumbing and electrical system of the house, masonry work, gypsum board and plaster finishes, and roofing. Parts, products, and pieces are assembled into definable parts of the house. These all require assembly of various raw materials to make a complete construction.

The drawings also indicate the items that are part of the house and have to be priced individually from specific manufacturers or suppliers, as opposed to items the contractors will fabricate. Often these are called buyout items, because the contractors or their subcontractors “buy” them from suppliers and vendors. A partial listing of some of these items includes windows, doors, appliances, architectural woodwork, lighting fixtures, and air-conditioning and heating units. The drawings you have made will indicate the number and sizes of these items, and the physical counting of these is an important part of the estimating process.

Another role the drawings play in the pricing of the house is that they help to define the limits of the construction and the access and boundaries of the site. The site plan will indicate other structures that will be present on the site, driveways or curb cuts and setbacks or major site features that cannot be violated. It can materially affect the price of the project if the site has limited access or is too small to easily stage deliveries of materials or if parking for workers is limited. This may require more frequent deliveries of materials or staging of concrete pours or other activities. If there are trees that are to be protected during construction, these may create access problems. All these considerations factor into the price of the house, particularly into the schedule and general conditions.

If the drawings illustrate scope and quantity of what is to be built, the specifications answer the question of what you are building. The specifications are the detailed directions, instructions, standards, and expectations you have for the project. Used properly, they work in tandem with the drawings to guide contractors as to what the components and assemblies of the building are and what standards for construction you have for them.

Usually these are bound in the form of a book or manual and are divided into sections using an industry standard set of guidelines for categorizing their contents. At a minimum you can provide two sets, but some contractors will want more to provide to their major subcontractors. If you provide two full sets and the contractor requests additional copies, it is reasonable to request the contractor to pay for these.

The most frequently used industry standard for organizing the specifications is the one defined by the Construction Specifications Institute (CSI). It breaks the categories of construction into areas or scopes of work based on roughly organized but inclusive categories of materials and labor. Each of these categories is given a numerical designation, and then the specifications are organized within these. Further breakdowns are included under each category number, and these can go down with increasing levels of detail to the individual components or assemblies of every part and piece of a project.

These are general categories and are grouped together for usually obvious reasons. An example of this system would be Division Six which is wood. Included in this division (among other things) are framing, framing materials, framing labor, cabinets and millwork, wood flooring, wood trim, and trim labor. Depending on the design of the house, some of this work would be completed by the same subcontractors, but not all of it. The subcontractor that provides the framing would not typically do millwork or the finished wood floors.

Specifications are often omitted from the materials provided for pricing and construction of single-family houses. Many architects see this level of detail as unnecessary in the documentation for a house. I have actually had residential contractors tell me they never look at the specifications in books and would prefer that I include the specifications in the drawings themselves. To some extent this is possible, and for certain types of residential projects this is practical and makes sense, but not for all. The information still needs to be provided, but in the design of houses there is a trend to use specifications to indicate a material or product to be used and for the subcontractor or supplier to provide the details and methods of its installation.

I have noted elsewhere in this book that some of our residential projects are really like small commercial or institutional projects, often with budgets of several million dollars. These same projects use exotic and expensive materials, assemblies, and equipment, none of which are in common use in many houses and are often unfamiliar to the subcontractors and suppliers who will be buying and installing them. In many cases the conditions outlined and required in the specifications are what qualify the subcontractors for the work to be done. It is the conditions for the work that are stated in the specifications and the contractual obligations they expressly imply that make some subcontractors decide the project is not appropriate for them to price, let alone build.

With many of our projects, we and the owners identify certain trades or work scopes that the owners will be providing directly to the project. Often these are subcontractors or suppliers selected for their special skills or expertise in an area of the project important to the owners or for some aspect of the design of the house. We try to limit these selections to key parts of the project as our role in the administration of these subcontractors becomes more critical and there is not always a corresponding increase in our overall compensation for the work that comes with selecting and coordinating them. Specific examples of areas where we feel this kind of preselection is logical include architectural woodwork, ornamental and custom metalwork, specialty finishes (faux finishes, marbling, Venetian plaster), mosaic or inlaid marble, and stone flooring. If we are using contractors with whom we have experience, or whom we have prequalified and whose work we have seen, then other trades capable of doing the work should be selected and qualified by the contractors as a part of their scope of work.

In our practice it is not uncommon for the millwork, kitchen cabinets, and other architectural woodwork to be purchased directly by the owners. This is also true of items such as appliances, decorative lighting fixtures, landscaping, swimming pools, security or AV systems, and specialty finishes (faux finishes, Venetian plaster). We indicate in the Instructions to Bidders, the drawings, and the specifications what these items are and what our expectations are for the contractor regarding this work.

Predetermined subcontractors, suppliers, and vendors need to be identified in one of two ways to the contractors so they will know to include these items in their price. In the first case, it is your clients’ intent that they be identified as subcontractors whom the contractors must utilize in the construction of the project, but they will work for the contractors directly. Simply put, the owner will select specific subcontractors or suppliers for the contractor to use, and the contractor will obtain pricing and include the work of these subcontractors in their contract and as a part of their scope of work. In this case you are specifically identifying the resource—the subcontractors or suppliers—and instructing the contractors to include them in their price to build the project. It will be their responsibility to contract with the subcontractors, to pay them according to the contract terms they agree to with the owner, and to coordinate and warrant the work when it is installed. For the contractors this requires understanding the scope of work fully and including any items not provided by the predetermined subcontractors or suppliers in their bid to do the project.

In the second case, the owners provide the work of these subcontractors and vendors at the owner’s cost, under an agreement executed directly with the subcontractors and suppliers. In other words, the subcontractors or suppliers will work directly for the owner. The contractors will need to understand this type of agreement fully so they know not to price this work scope on their own. Additionally contractors will need to provide funds in their pricing to pay for their time to schedule and coordinate these subcontractors and suppliers when they are doing their work on the jobsite. Finally contractors will again need to know what work associated with the scope the subcontractors will not be doing so that the contractors can provide for the cost in other areas of their price. For example, if the owners select and intend to pay for a subcontractor to do faux finishes on walls within the house, the contractors will need to know to what level of preparation the walls are to be completed. Will the subcontractors require a smooth surface already taped and bedded, or will they want to do this work themselves? Will sizing or a primer coat of paint be required before they do their work? Will protection need to be put in place by the contractors for other adjacent work near the areas to receive the special finish so they are protected? The work the subcontractors are not planning to do will need to be provided by the contractors, and so a thorough explanation of the scope is necessary.

In both cases it is necessary that the contractor be able to communicate directly with the predetermined subcontractors and suppliers to fully understand their expectations for the project and what the subcontractors are agreeing to do. Reviewing the scope of work directly with subcontractors and suppliers is a form of due diligence for the contractors and helps to avoid possible misunderstandings later. If the contractors do not have this opportunity to understand the scope of work directly from the subcontractors or suppliers, conflicts or areas that are not covered in the bid/pricing may arise that in good faith could not have been foreseen by either party. Unfortunately these conflicts will not be identified until the work is ready to be installed, possibly during actual construction.

We find that providing the contractor with a copy of the soils report is useful, even if our structural engineer has incorporated the recommendations into his or her foundation design and specifications. The soils report includes information that can be helpful to the contractor in understanding why the structural engineer has selected the foundation type and why it is detailed the way it is. This is also helpful to combat the unpleasant contractor tendency to find the structural engineer’s foundation design “overengineered.”

Depending on the part of the country where you are building, the soils report also provides useful information for the contractor for parts of the project beyond the foundation of the house. It will contain recommendations for site paving and the attendant soil preparation. It is a useful tool for pool contractors to know the conditions in which they are about to price and construct a pool. If your project requires the contractor to make utility connections, it may be helpful for the subcontractor providing this work to know the conditions to be dealt with when excavating and placing pipes and other lines.

When we design subsurface construction into our projects (basements, partially submerged rooms or spaces), it falls on us to specify and design the waterproofing system that will protect the spaces from moisture and condensation. The soils report can provide information that is helpful in the selection and design of these systems and how we handle subsurface moisture and drainage. If for no other reason than to help the contractors understand our design criteria, we provide this information to them.

The adage there can never be too much information is always true in pricing a residential project. Providing conscientious contractors with additional materials for their evaluation and understanding of the project should help in the creation of a complete price. Other miscellaneous items that may be helpful based on the site and its individual conditions are discussed in the following sections.

Most incorporated entities will require their permit sets to include a site survey with a legal description of the property showing meets and bounds as well as any other easements or encumbrances on the property. As suggested in an earlier chapter, it is useful to have this drawing incorporated as part of the cover sheet for the project. We usually ask our clients to provide a topographic survey of the site as well; in the best case it is part of the same document. A topographic survey is useful for the contractors to understand the conditions of the site, particularly if there are significant grade changes or potential drainage conditions they will need to take into consideration during the construction of the project.

We often provide a map to the site where our project is being constructed. We always include a map of the area with the site identified, but if the project is in a remote or rural area, for instance, a second home on a lake or rural property, providing a map and directions to the site is a courtesy that is helpful to the contractors.

With the availability of Internet-based mapping websites, such as MapQuest and Google Maps, it is relatively easy to provide this information in complete and graphic detail to the contractors.

Most of our work is constructed in a large urban metropolitan area made up of dozens of incorporated communities or entities, each with their own permit and approval processes and expectations for the contractor. An important part of our Instructions to Bidders is the intention that the bidding contractors familiarize themselves with the specific rules related to the particular community in which we are building and to include the costs of abiding by these rules in their pricing. Providing the contractors with the address and pertinent contact names at the permit authority having jurisdiction is useful and often helpful. We like the contractors we are working with to know the rules and regulations associated with building a house or doing a remodel in the jurisdictions where we are designing.

Examples of the kinds of information that the contractor needs to know and understand when working in a specific location include rules regarding foundation surveys before pouring a new foundation to ensure it does not encroach on a setback or property line; whether there is a designated trash hauler required to be used in a community; requirements for placement of stormwater management and erosion control; and at what stages in the construction process inspections will be required. Some of these requirements have cost and schedule impacts for the contractors, and we feel it is valuable for them to have an understanding of these when they are pricing the project.

At various times in my career I have been involved in projects where the contractor paid for the drawings used to bid the project. But my experience has been that for houses at least two to three sets should be made available to each bidder, and the owner has traditionally paid for these. Additional sets beyond these two or three are generally done at the cost of the contractor.

Some architects will require the unsuccessful bidders to return the sets of pricing materials after pricing is complete. In theory, this allows those sets of bidding materials to be distributed to the successful contractor, to whom the project is being awarded, saving on the cost of reproduction. My experience has been this practice is rarely useful; once a successful bidder is selected, there will almost always be revisions to the set that will render the bidding documents obsolete. This is also true after the project is permitted and any pertinent comments from the permit review are incorporated into the set. Waiting to create a set that is “issued for construction” is a good practice to make sure the contractors are starting construction with all the materials they need in place to work. Holding off on signing the final contract until this set is in place is a useful practice too.

The process of residential construction pricing is often hard to fully understand, even for those of us working in the profession each day. Depending on the contractors and how they price their work, much of the work may be done by a small group of subcontractors, unlike in a commercial or institutional project where subcontractor specialization is the norm. It is not uncommon in the construction of a house to have subcontractors loosely characterized as “the framers” who will dimensionally lay out the construction, frame the house, apply exterior finish materials if they are siding or panel products, install the windows and doors, hang sheet rock, do the finish trim work, and install the roofing. This kind of generalization is not uncommon in residential construction and is often a competitive pricing edge for some contractors whereby they can use their own or a limited number of workers to build the house.

In a volatile construction market, the cost of building materials and labor can fluctuate rapidly and render inadequate and incorrect any early budgeting expectations you and your clients have for the project. How the project price is derived by the contractors, through a competitive bid or negotiation, is often directly reflected in the number you get for the cost of the house. In bidding a job, the contractors are by nature more willing to go with what they can clearly see in the bidding materials as opposed to asking questions and filling in any perceived blanks with their assumptions that could put them at a competitive disadvantage with a possibly higher price. Another important factor is the experience and understanding of the contractors who provide that pricing. Selecting the appropriate contractors to price the project is critical to obtaining an accurate and representative number for the cost of the house.

Selecting the contractors to negotiate a contract for construction or bidders to competitively bid the project is an important task that the architect usually undertakes in the process of getting the project built. Most clients do not have ongoing relationships or experience with general contractors whom clients are able to suggest as possible resources for building their new house. Even if they know potential contractors, clients will not understand how to evaluate whether contractors are qualified to build the house. Clients will naturally rely on your professional experience to identify potential contractors based on your knowledge of the contractors’ work. Hopefully you will have contractors to recommend for pricing or bidding a project where your experience is gained firsthand in building other projects with them. If not, you will be integral to the process of selecting and qualifying the potential contractors.

How do you identify who will be bidding the house? When we bid or negotiate a project, we try to match contractors with the project. Different projects have a variety of components that make them better suited for some contractors than for others. Some of the contractors we have had experience with are considered a good value relative to their cost and provide a serviceable product at a modest cost. Put another way, they are a lower-cost, but competent provider able to deliver a certain kind of product and meet specific expectations. These contractors would not necessarily be right for an elaborately finished house with many specialized conditions that require careful execution of refined details. For projects with these requirements we look for those contractors who have a project management base and supervisors with experience pricing and executing complex projects, with a strong component of craftsmanship in their work, as well as a thorough understanding of how to read and analyze plans to anticipate the construction activities necessary to execute the details correctly. The prices for any given project would be much different from each of these providers, as would the ultimate results.

When schedule is the overriding concern of clients, we look at how we can facilitate the fastest completion of the project, and a typical residential contractor is not the right resource. Occasionally we design a project we feel would be best executed by commercial contractors, and so we utilize them where possible to help us with projects of this nature. The knowledge and experience they bring to the project, in addition to their ability to move the schedule along in a more expedient manner, make them good choices for some types of projects and clients. Usually they will have higher overhead, and a direct result is they are more expensive to use; but the benefits are to be found in their ability to schedule and coordinate multiple subcontractors which generally contributes to a faster delivery. The subcontractors they will use are likewise often more expensive, but have larger staffs and stronger purchasing power, so these subcontractors can expedite work in most circumstances. If the clients are willing to accept the additional premium to cut the construction time, a commercial contractor may be the right choice.

For various reasons you will not always have an opportunity to work with the same contractors every time you build a project. This is not necessarily bad; you always have to work with someone for the first time, and it is the way you meet good contractors as well as those who may ultimately disappoint you. Qualifying them before they price, let alone build, one of your projects is an important responsibility for you and your firm. When you are considering new contractors for the first time, it is always good practice to go to visit projects done by them to evaluate the work firsthand. In many cases it is good to encourage the owners to visit these projects to see the contractors’ work too. This helps with grounding the clients’ expectations for the final product and allows the contractors to point out areas of the project in which they take pride or where their particular expertise can be seen. Many times we visit projects that from a stylistic viewpoint are dramatically different from the house we are planning for a specific client. Even when seeing these sometimes stylistically disparate houses, we can begin to understand a sense of the attention to detail and quality of execution the contractors can potentially bring to our project. In our practice frequently we work with a contractor who is known for building fine period houses, but when working with our firm is excellent at executing contemporary spaces and details. Unfortunately the opposite can also be true. Many contractors who build traditional homes have become used to having trim and moldings to cover joints and do not have the experience or a subcontractor base capable of executing minimalist or zero detailing.

If you have never worked with contractors, it is also useful to check their references. This process can be tedious and sometimes misleading; you can get very good references from nonarchitects for a contractor who was pleasant to work with but does marginal or careless work. We are always interested in whether they have worked with architects on their projects and at what level of involvement the architect was part of the construction process. If the architect’s responsibilities ended at the completion of the construction documents (which is sadly often the case) and the owner managed most of the process and design decisions, then the contractors may not have the right experience to work closely with us. We like to check references in several ways, besides the obvious request to the contractor for a list of references to call. First, we encourage the contractors to provide the addresses of all their residential work for the last 5 years. This is not too far back to ask for as most houses take between 12 and 24 months to build, which suggests possibly only two to three generations of houses completed in that time period. We then cross-reference the addresses of the houses they list with the names and addresses of the clients they ask us to speak to for references. If the list of actual houses is dramatically different from the addresses of the clients used as references, it is not unreasonable to ask why those clients cannot be called for a reference.

When calling the contractors’ former clients, we find it is best to check the references of more than one. Occasionally we will detect a pattern of only good references, which can be taken as a good sign, or in another reading it represents a careful selection of the references by the contractor to be called. When we call the references, it has been our experience that happy customers will be glad to share in great detail all the things the contractor did for them. Often you can detect in calling a reference when they were not fully pleased with the contractors’ work, but feel obligated to be supportive or at least not negative. Sometimes you just get bad references, and you yourself question why the contractor would give you a contact who might not have good things to say when you call. In the end both good and bad references are helpful, and we like to get a balanced view of the contractor. In rare cases we have visited a house with a contractor where the owners could only point out the problems or disappointments they had with the final result, but to us the house was well done, competently executed, and an excellent example of the contractor’s capabilities. We try to be fair when evaluating what we hear; we have had clients for whom we did very good work who could not be pleased by our efforts, so we try not to hold one bad call among many others that are positive as a deciding condition in our approval. Sometimes the best proof is the house itself, and it is good to remember that we cannot always meet our clients’ expectations. The same is clearly true for contractors.

We are often contacted by contractors with whom we have not worked who want the opportunity to bid one of our projects. If the opportunity presents itself, we have prequalified them, and there is a competitive bid situation, often we will include them in this process. On other occasions we are approached by contractors whose reputations we know from our peers or other clients and whom we are reluctant to consider for our work. Our adverse knowledge would suggest we would not voluntarily work with them. If we know we do not intend to work with them, we try to be honest and tell them it won’t be possible for them to bid our projects. It might seem convenient to allow them to be included on a bid list as a way to allow them to think you would consider them, but properly pricing and bidding a job takes time and resources, and we make it a practice never to allow anyone to bid one of our projects whom we would never consider a possibility to be awarded the project. Neither of us needs to waste time, and we have an obligation to be honest with them about our likelihood of never working together.

On some occasions our clients have approached us with a contractor to whom they fully intend to award the project, but the clients want the contractor not to know this. The expectation is that he or she will provide the lowest possible pricing if they are not sure they will get the job. Often we feel confident that a particular contractor would be a good choice too, but the clients want the contractor to competitively price the project against other contractors to create a sense of thrift and force the favored contractor to provide the lowest price possible. We flatly refuse to engage in this process and try to help clients understand that if they ask multiple contractors to bid the project competitively and use their time and resources to put pricing together, the contractors should out of fairness have the opportunity to be awarded the project. If the clients are really convinced the contractor is right for the job, there are other ways to get the lowest qualified price without asking other contractors to participate in a meaningless pricing exercise.

One type of contractor that our experience has shown to be a challenging match for building an architect-designed house is the typical custom home builder. The word custom, like the word luxury, has a variety of meanings and in today’s use can most generally be taken to refer to a builder who constructs a small number of projects as opposed to a production or merchant builder who is working at the scale of a large development. Although the contractor may have tremendous residential construction experience, it is not in building houses that were designed and detailed thoroughly with specific intent in the way they are constructed and finished. Under most circumstances we would not consider these builders as qualified contractors for our projects. Unfortunately we do have clients who have been referred to these types of contractors by friends or associates and who ask us to consider them for their projects. We begin by explaining to the clients the difference between custom builders and general contractors in the hope that once clients understand the differences in these two groups’ experience and motivation, the clients will allow us to exclude them from bidding.

These types of builders don’t usually execute highly detailed projects in the sense we architects think of them. Their subcontractors often do not have the skills or expertise to build to our expectations or coordinate carefully with other trades. Many of these builders construct significant homes with substantial area under roof and elaborate finishes, costing significant amounts of money, so our explanations of why they are not the right choice to build our clients’ house is often not fully understood or appreciated. Many clients will not be able to pick up on the subtleties of this discussion, especially if the custom home builder is able to discuss pricing for her or his typical projects with them. Clients will find it hard to believe the builder can deliver such a high level of finish and so much square footage for the prices they will be suggesting. This situation will put you in the awkward place of educating your clients, sometimes against their will and inclinations, on the differences; and as with any discussion involving money, their emotions will play an important role in how they accept what you are telling them.

If you are forced to include a custom home builder in the pricing process, one way to equalize their numbers is to require them to bid to your plans and specifications without deviation. Ask them to make their suggestions for how to “save the clients money” in the form of specific deductions to be made from a list provided with their bids. When forced to price it two ways, the way you have documented it and “the way they would do it,” you have a tool to use to explain the differences to your clients. Using this list as a comparison, you can have a meaningful discussion based on more than just your professional sense of why the contractor is unqualified. In the end the lower pricing may be too attractive for the clients to resist, and you can be assured you will be going into the construction process with conflict built into the project.

An important consideration for the architect to discuss with clients is the best way to price the project. Several possible scenarios exist and all offer both pluses and minuses. We have had successful experiences with all the methods discussed below and, to be candid, have been disappointed by construction projects that were priced under every one of these scenarios too.

When asked by the clients to bid a project, we like to ask them to articulate for us what they hope to achieve by a competitive bid. Usually they will tell us the lowest price, based on their understanding of the way competitive pricing works. We tell them we like to take an approach that will get them a competitive bid, but not one that will take the lowest bidder’s price without qualification. We discuss with them other possibilities and make sure they understand it is not in their interest to come to contract with an incomplete or erroneous price from a contractor.

Some of the more basic versions of how a project can be priced are discussed below including the pros and cons associated with each. These descriptions are intended as a guide for each method of pricing and provide an outline to be used in discussing these with your clients.

Competitive bidding suggests a “hard” or final bid for the project by multiple contractors using identical sets of documentation to arrive at an estimate of a total cost of the work to build the project. This method is one that is most often taken for granted as an industry standard by clients. Often they believe that competitive bidding is the best way to obtain the lowest price. It has been my experience that in the case of residential projects this is not always true.

The nature of a competitively bid project suggests that the competing contractors will try to gain advantage over one another by carefully trying to determine how to price and build the project in as efficient a manner as possible. These contractors will also solicit bids or pricing from one or more subcontractors from whom they expect a similar approach to pricing. The desired result is a comprehensive cost for a complete project with the lowest possible price. This is the primary advantage of the competitive bid as a way to obtain pricing for a project.

A significant drawback in the bidding process for the architect is the possibility that there are omissions or coordination errors in the documents that can lead to their being excluded from consideration in the contractor’s price. The burden of making sure the bid documents are complete and well coordinated under this scenario falls to the architect. Because of this you as architect should not look lightly on competitive bidding as a thing to be undertaken without knowing your clients may want to pursue it early in the project. If we know that this is the way the project will be priced, we provide a different level of documentation for the project than we do when we negotiate a price. This is not done because we can cover our mistakes or omissions better with negotiated projects; but if our clients desire a hard bid, we need to be prepared to provide an acceptable and complete level of documentation for this to happen.

One unintended consequence of the hard bid process is the opportunity for the bidding contractors to exploit problems within the documents to provide lower pricing, either because they miss the problems and so don’t allow for them in their bid price or because they do recognize them and use these omissions or conflicts as an opportunity to provide lower pricing. Either way the result is the same; when in the course of construction the problem is encountered, it will not be covered in their price and the result will be a change order to provide the work in the project.

A hard bid also requires the architect to manage the bidding process more carefully and to document calls and the information flow in a fair manner to all the bidders. Contractors who find errors and/or omissions or just ask for clarifications and communicate with you about them will have a better understanding of the expectations for the project. By issuing addendums during the bidding process to all the contractors, you can distribute this information uniformly, thus ensuring they will all price it in a consistent manner, based on the same assumptions.

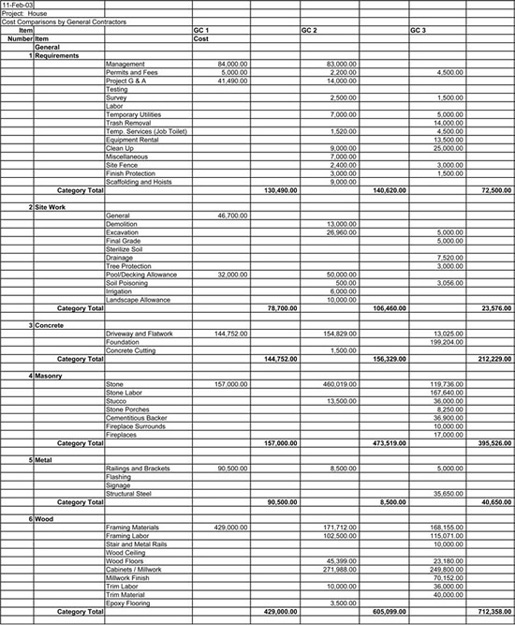

Traditionally when competitive bids come in, they are intended to be a final number for the construction of the project indicated in the bidding materials. We find this to be impractical, especially with houses. Below is an example of a Bid Tabulation form we use with our projects that allows us to present to our clients each of the competitive bids in a format that illustrates the numbers and how they deviate from one another. With the example shown in !Fig. 4.1, you can see that the overall prices vary by about 20 percent between the high and low bidders, but there are a great many similarities between the various categories of work.

When you are looking at the prices provided by the competing contractors, conventional wisdom suggests it is often a good sign if the prices fall within a close range and the competing contractors share what appear to be similar assumptions for general conditions, profit, and the schedule for construction. This allows you to consider each of the contractors based on individual merits and approach to the project and not solely based on price.

When you are comparing various competitive bids and there is a significant discrepancy between prices, with one being particularly lower than the others, you will often have to deal with the very real human response of your clients to want to seize on this attractive lower number. You will want to understand and qualify why the contractor has submitted a decidedly lower bid and perhaps disqualify it completely from consideration. This can potentially put you at odds with your clients, and they may even take a position that it’s too bad for the contractor who made the mistake assembling the price, that by submitting it the contractor is obligated to honor it. While this may be true in the strictest sense of the intent of a competitive bid, it is critical to help clients understand that a bad bid is sure to cause problems during the construction process. The contractor’s financial well-being directly corresponds to the success of the project, and in a business sense it is impractical to expect the contractor to intentionally deliver best efforts while losing money and putting his or her company at risk.

FIGURE 4.1 Typical form for evaluating multiple contractor bids when prices are obtained through competitive bidding.

We also request the contractors to provide an outline schedule for construction as a part of their hard bid pricing. We want to understand how they see the project unfolding and how long they feel it will take to build. This schedule should help to explain their assumptions about the cost of their general conditions, as their estimates of how much time it will take to build the house will have direct bearing on these costs. General conditions are usually calculated on a monthly or weekly basis and include such things as the cost of supervision, insurance, progressive jobsite cleanup, trash removal, and temporary office costs. The longer they anticipate the project taking, the higher these costs will be. This is important when evaluating each of the prices from the competitive bidders. If one or more have considerably longer schedules, it is worthwhile to review this with them and understand their assumptions. Often we have discovered issues with material availability or product specification through a more thorough investigation by one contractor during the pricing process that made that contractor’s schedule a more accurate representation of the time it would take to construct the project.

It is important to remember that these outline schedules from the contractor are assumptions of how long the project will take to build, not an accurate critical path schedule. Explaining this to your clients helps to keep them from being disappointed later when a more detailed schedule is created. As discussed above, in most cases we will not have obtained the building permit at the time we go out for competitive pricing. Once the actual permit process is incorporated into the schedule, it may require a longer time to obtain approvals and incorporate the permit comments into the work of the contractor. Additionally, if the owners elect to make changes in the project after the bids are received, you will require additional time to revise your drawings and the contractor to price these revisions. In most cases this outline schedule will change, and the clients need to be prepared for that eventuality.

Another way to engage with a contractor, and one we prefer for our residential projects, is to negotiate the price and contract terms with a selected and prequalified contractor. In negotiating the project with one contractor, you are agreeing to work closely with the contractor to help price the project consistent with the clients’ goals and expectations for quality and cost. It can be difficult to explain to your clients how this will ensure for them the lowest qualified price, but in our experience it is a more successful process for pricing a house than a competitive bid.

Many of our clients have the perception that a negotiated price does not provide an incentive for the contractor to provide the lowest cost for the work. To help your clients understand that a negotiated price does not allow contractors to charge whatever they want to build the project, and that there can be protections in place that manage contractors’ costs, sometimes requires a prolonged period of education and in some cases some successful examples from other projects you have priced in this manner. We often begin by citing the obvious advantages and how they affect not only pricing, but also the contractors’ attitudes and obligations for the project. This again refers to the importance of the ideas that an incomplete price for the work will potentially lead to conflict during the construction process and that the goal of pricing the project should be to obtain the lowest qualified price. Negotiation of the contract allows the contractor to be an active participant in fully qualifying the price for the work.

While you are working with your clients on the design of their house, you will begin to understand their personalities and the way they best relate and communicate with people. Based on this experience, you will be able to understand which contractors you have had experience with that would be best suited to working closely with your specific clients over an extended period. Some contractors are abrupt and professional, not given to personalizing their relationships with their customers, and for some of our clients this is the right personality to work with them. These clients appreciate professionalism and are not inclined to build a relationship beyond fees for service even with us whom they have spent several months helping to understand their lifestyles, personal needs, and expectations. Clients fully expect to pay for services and receive the value of the work in return, without any long-term relationship other than in a business sense. Other clients are interested in the experiential aspect of the construction process and want to engage with the contractor, having her or him provide input and commentary, and in a case like this a more genial and social person is more appropriate. It is not unusual for clients building their “dream house” to visit the site every day and in some way expect the contractors to take a moment to show them progress or explain the activities underway. If the contractor sees interacting with the client as a burden or a distraction, then this contractor may not be the right match for certain personalities. This is where your experience during design should help you select possible contractors who may best fit your clients’ needs.

Once you have identified possible candidates to build the house, you can arrange a series of interviews and tours and a viewing of other projects. If you fully understand the capabilities of all the contractors and have prequalified them to do the work, then you can allow the owners to select the person with whom they are most comfortable. If the clients still want to add a competitive element to the process before they begin to negotiate the actual cost of the job itself, you can have all the prequalified contractors develop a price for their general conditions on a monthly basis based on their understanding of the project provided by you. Additionally you can ask them to provide the fee they would charge for their profit markup on the subcontractor work and other direct costs of building the house. If you indicate to the contractors that the selection process includes their being evaluated in this manner, there is an element of competition in place and hopefully it will offer some comfort to the clients to know they have obtained a reasonable cost for the work.

Explaining the advantages of negotiating the project with one contractor to your clients should include the following considerations.

First, by negotiating a price with prequalified contractors you are creating a partnership to build with them the project. They are part of your owners’ team, along with you (the architect) and your consultants. The contractors now have a vested interest in thoroughly understanding the scope of work and the various components of the project for them to successfully do their job. Their fee is already established, as is the cost of the general conditions, so you can focus on helping them fully understand the project and completely accounting for all the scope of work.

Second, the contractors now have the opportunity to fully familiarize themselves with the scope of work to be done and to schedule it appropriately to complete it as quickly as the expectations for quality will allow. Since contractors will be interacting with the owners on a regular basis, it is not inappropriate for them to ask for an explanation of the owners’ expectations for quality relative to cost for the work of the project. Contractors are in a unique position to propose the possible range of prices and the corresponding values of the work to be done. With your guidance and input they can be part of the selection process for building materials and components and can help the owners understand the cost-to-value ratio of their choices. This is also true of finish materials, appliances, and other equipment to be purchased for the house.

Third, the construction work on the house itself can start earlier as you are eliminating the time required for the competitive bidding process. With the contractors on your team, you can submit for permit at any stage in the completion of the construction documents that will be adequate for the permit review submittal but not necessarily for the competitive bid. Since the contractors are part of the team, you can distribute work to them as you complete elements of your documentation, not when you have it fully completed.

Fourth and perhaps most important from your point of view as the architect, the contractor can provide real-time pricing for the project as you are completing your drawings. It is useful to you and your clients to know the cost status of the project on an ongoing basis so that value engineering is integral to the design process, not an activity to be done after pricing when the client is suddenly (and unhappily) faced with possible reductions in scope or finishes for the whole project to bring it into an acceptable budget.