DEAR Charlotte,

“Did Emily tell you about the bed? I think she might be right, though I did not tell her so. We should be moving to lodgings now quite soon. We must make quite sure I am in 1918, not you, the day we move. Emily would be so worried if you got caught then, and I in your time, and I would be so worried about her.

“Yours sincerely, Clare.”

This Monday, there was no sign of Bunty at breakfast.

“That rotten Miss Wilkin! She told,” Emily said. “You know, about playing soldiers in the park on Saturday. Poor old Bunty’s in fearful trouble now.”

“You were just as bad as Bunty,” Charlotte pointed out.

“I know; wasn’t I lucky not to be seen first,” said Emily.

At prayers, Ruth was subdued, rather red-eyed, as if she had been crying. Miss Wilkin looked unhappy, too, twisting her engagement ring. Bunty seemed more cheerful than either of them, even though she had to sit on the platform with the staff. She grinned and wriggled on her chair, while Charlotte wondered how she could endure the embarrassment of being there at all, before all those eyes, let alone so cheerfully.

After Miss Bite had read out to the school her usual reports about the war, she spoke of Bunty in extremest gravity and sorrow. She was a tall, solemn lady who made no attempts at jollity like Charlotte’s own headmistress, Miss Bowser. She wore a high, old-fashioned collar and steel-rimmed spectacles. The only exception to severity was her hair, which she wore piled on her head but which, being very thick and abundant, edged its way out of an armory of pins.

Bunty, she said, had let the school down, let herself down and the girls she had led astray; let her country down in these grave days; disgraced herself, her school, her king, her country.

“The way she spoke, anyone would think Bunty had been rude to God,” said Emily at the midmorning break.

“Emily,” cried Charlotte, “you mustn’t say things like that.”

But though she was shocked, she wondered, disconcertingly, if she would have been quite so shocked if she had not known Clare would be.

And Emily said gleefully, “You rise just like Clare when I say that sort of thing, except that I think she’d have said it was wicked to say that, too. I wondered if you’d rise. That’s why I said it, as a matter of fact. Anyone would think you were the same person, wouldn’t they?”

Even so, when someone handed Charlotte a letter, Emily snatched it away and ran off by herself to read it, crying over her shoulder, “It’s my letter from my father, and Clare’s, but not yours at all; you’re not to look at it.”

Charlotte walked on alone along a gravel path. It was dry again this morning, yet much less warm, with something in the air that made her feel curiously sad. For the first time she was glad of her thick school clothes. She had awakened briefly in the night to hear the wind blow and had not known which time she had heard it in, her own time or the past. There was a wind today most certainly. It had blown the orange leaves from the ends of chestnut branches and yellow ones from the edges of the limes. It blew them along the path toward her with little dry rustling sounds, until she turned into shelter round the corner of the school buildings and met Elsie Brand, crying over a letter.

“Are you all right, Elsie?” she asked anxiously.

“Yes,” said Elsie Brand.

“Are you sure?”

“Yes,” said Elsie, sniffing. Charlotte walked with her for a while, to keep her company, but need not have bothered for all the notice Elsie took.

Elsie Brand was a very ugly girl. She had big uneven teeth and dust-colored hair. She had a nose big enough, Bunty said, to hang out a flag on.

Neither Bunty, kind as she usually was, nor anyone else made the slightest effort to be nice to her.

“Her name is Brandt really, not Brand. Her father’s German, you see,” Bunty had told Charlotte and Emily conspiratorially. “My mother says all Germans ought to be interned; they’re all spies these days, even the ones who’ve been here years and years.”

“You must be careful what you say in front of her,” whispered Ruth. “She might send letters to Germany and tell them things.”

“Whatever sort of things would she have to tell?” asked Emily.

“Well, if you said my father was with the army in France, she might write that.”

“Well, that’s silly; they don’t need spies to tell them there’s an army in France. Anyway, no one can send letters to Germany.”

“And all our letters from here are read anyhow,” added Charlotte.

“She could write them in code, though, and her mother could send them on by submarine.”

“I thought you said her father was German, not her mother.”

“Her mother must like Germans or she wouldn’t have married one.”

“Well, I think it’s silly. My Aunt Dolly says all this talk of spies is silly. They’d never have let Elsie in the school if she was a spy. Besides she’s much too ugly,” said Emily.

“She’s not really very ugly, Emily,” protested Charlotte.

“My mother says there are spies everywhere, and you can’t be too careful,” said Bunty.

As she walked with Elsie, Charlotte remembered this conversation. The wind caught at Elsie’s letter, tugged and rustled it between her hands, and Charlotte glanced sideways at it, curious. But immediately she told herself not to be so silly, jerking her eyes away and then back to smile at Elsie, blushing a little.

Elsie did not even glance at her.

•

Despite all the care they took, mistakes were bound to happen now and then in their peculiar circumstances. Teachers had been lenient with their mistakes at first, since Clare and Charlotte were new to school, but they became increasingly less lenient. Once between the two of them they forgot a Latin exercise, and another time both Charlotte and Clare drew a map of Africa for Miss Wilkin’s geography class to Miss Wilkin’s decided puzzlement.

Worst of all, perhaps, were the piano lessons. Clare had already been learning the piano for four years, Charlotte for barely a year, and though Clare said she tried to play badly in her lessons, she must often have forgotten, judging by the way the teachers reacted to Charlotte’s playing.

“You’d almost think, Charlotte,” said her own teacher exasperatedly one day, “that you changed into different people from one lesson to the next.”

Clare’s teacher said nothing. She wore ties like a man’s and brown suits made of pin-striped cloth. She was white and old as a bone, as rigid, too, and she rapped bones, knuckles hard with a ruler when fingers erred. Charlotte’s knuckles she rapped at all the time. Charlotte dreaded her lessons, though she was learning to play scales faster than might have been possible otherwise, practicing furiously in the narrow drafty cells that were practice rooms.

She felt she had to island herself now more and more, to draw in bridges, like a knight barricading himself in his castle. Otherwise she feared she would give herself away, asking a question, for instance, about something she ought to have known if she spent every day in the same place and time, or doing or saying something that would look odd because serious, conscientious Clare would never do or say such things.

This vigilance was tiring. Charlotte began to think that the one thing she really wanted was to be by herself for a while, for it seemed impossible ever to be alone at school. It was impossible in Clare’s school, at least. But in her own time, each day after games they had more than half an hour to change before work started again. One afternoon she dressed herself as fast as she could.

“Would it matter if I went outside in the garden for a bit?” she asked Elizabeth, who she thought might be less inquisitive than the rest.

“Goodness, whatever do you want to go out now for?” asked the sharp-eared Vanessa.

“I’ll come with you if you like,” Susannah offered kindly.

“No, it’s all right, thank you, honestly.”

“Of course she wants to go alone,” said Vanessa. “Charlotte never wants to do anything with anyone else.”

“I want to be alone,” cried Elizabeth, suddenly jumping about the room and chanting it—“I want to be a-l-o-n-e, want to be a-l-o-n-e”—giggling loudly in between, disconcerting Charlotte, who was not yet used to her sudden turns from silence into buffoonery. But in the disapproving attention this drew from both Janet and Vanessa, she was able, quietly, to escape outside.

She did not feel comfortable till a wall of shrubs hid her from the eyes of the school buildings, when immediately there rushed hard into her a most curiously wild kind of happiness that made her tremble, yet sharpened her mind inside.

The September sun was marmalade color on the brick wall that divided garden from river, reminding her of home, of Aviary Hall. Though why, she wondered, should remembering home make you so happy one time, so miserable another? A wren sounded nearby—its sharp song ending in a clocklike buzz. Another one answered it farther off. Charlotte sang, too, under her breath, wanting to sing louder but not daring to, letting herself out instead in a series of leaps and gallops, more suited, she thought, to someone of Emily’s age, but exciting, an untying and unloosening, too.

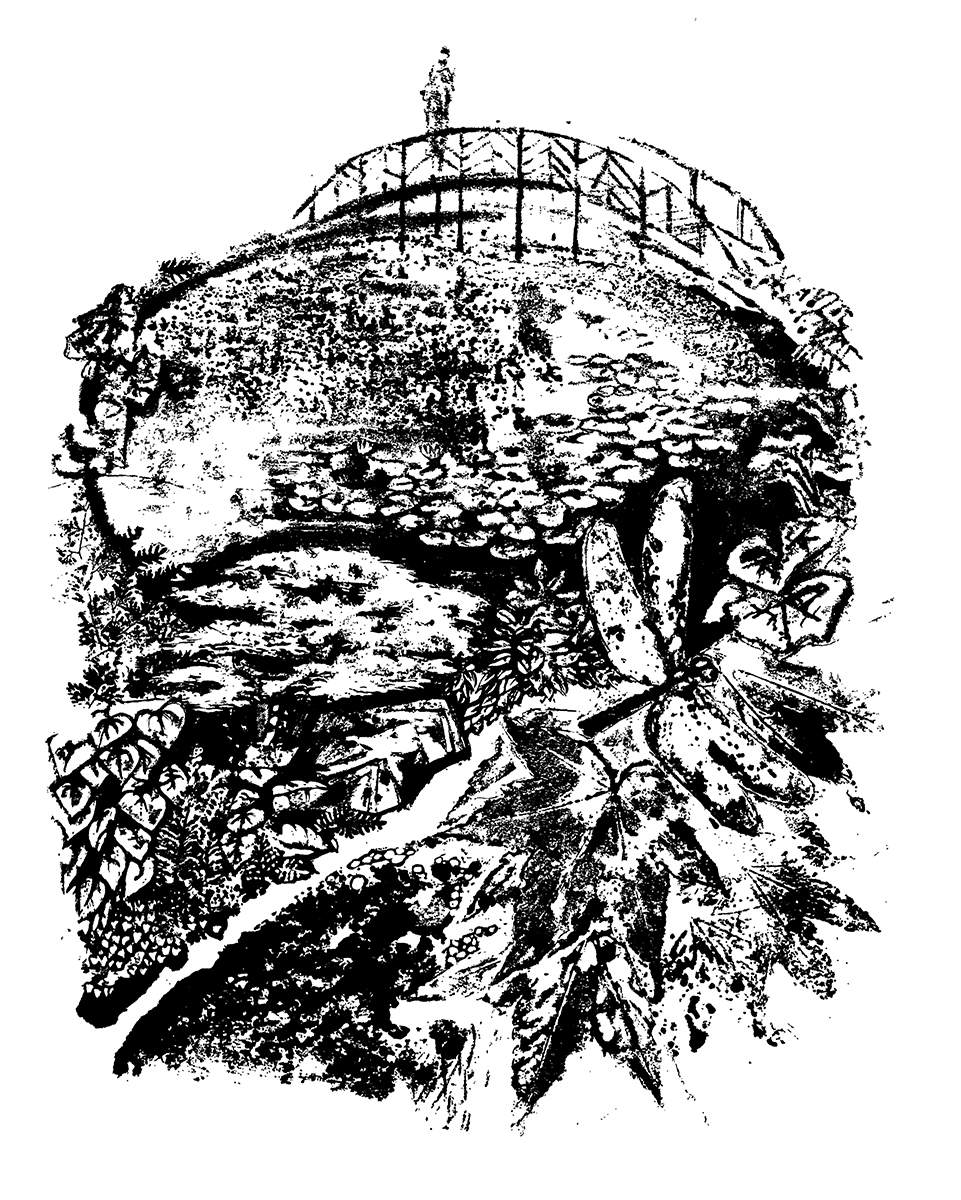

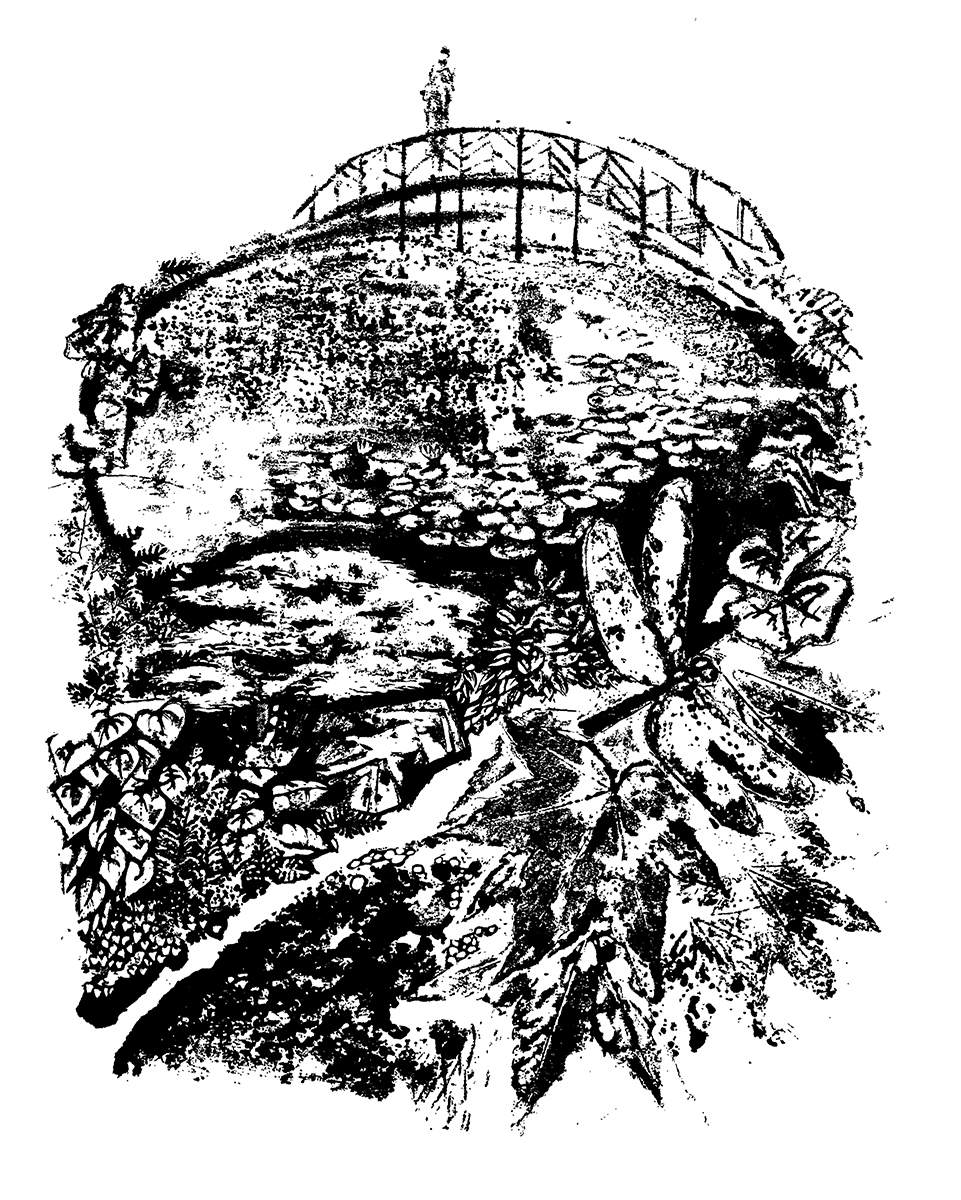

The thickening bushes slowed her down at last. She crept tentatively among them, expecting to find herself in a cave of leaves and twigs, but emerged instead into the strangest kind of garden, very overgrown. All its trees and bushes were curiously shaped and colored; little flattened trees with twisted branches and red and feathery leaves, the redness too pink to be merely an autumn color; coppery bushes with long leaves, others with sprays of round leaves widely spaced, all seeming to absorb the sun’s warmth and light and reflect it back again. Set among them was a pond of thick black water half covered in lily leaves, the midges wavering over it in a cloud, and dragonflies flicking like little helicopters. There was a bridge very steeply humped, many slats and railings gone, the rest showing faded and blistered remains of a dark pink paint. On the far side of it, leaning on one of the only firm-looking pieces of rail, there stood, staring at the water, a tall, fair girl.

Charlotte stepped back at once seeing her, reluctant to explain herself, especially to a senior girl as this one seemed. She was uncertain in any case whether she should be here or not, whether it was out of bounds. But the layer of leaves and twigs from the bushes spat beneath her feet, and the tall, fair girl turned round.

“Hello,” she said. “It’s Charlotte, isn’t it?” It was Sarah. Her voice sounded much nearer than the bridge looked. Perhaps in the late slanted sunlight the lake gave merely an illusion of size.

“Wait a minute, will you? I’m just coming.” Sarah was with Charlotte quickly, just half a dozen steps it seemed from the center of the bridge, including the leap she had to make over its gaping holes.

“Well, how is it going?” she asked, flicking scraps of paint from her dark blue skirt, looking at Charlotte in an intent and curious way.

“Very well, thank you,” replied Charlotte uncertainly. Someone whose expression was so hard to interpret was not someone to make you feel at ease, especially when they stared at you as hard, as strangely, as Sarah did. Charlotte’s head prickled, the midges having begun to bite. It was a relief almost when an airplane buried them in sound, making talk impossible.

“It’s supposed to be Japanese, this garden,” said Sarah abruptly when silence fell once more. “No one has touched it for years, of course.”

She hesitated. “Come on, we ought to go or you’ll be late for prep.” Again Charlotte had the feeling there was something she wanted to say, other than what she actually did.

Sarah knew the path out of the garden, and they went along it, but without hurry. It was almost the first time since she had come to school that Charlotte had been alone with someone other than Susannah or Emily, and there came over her a sudden huge longing to tell Sarah, tell her about what was happening. She half stopped, opened her mouth, turned toward Sarah, but the sight of that remote pale face checked her. She could have spoken to air perhaps, but not now to anyone she was looking at.

Sarah, however, stopped suddenly. Gazing straight in front of her, still without turning to Charlotte, she said quickly, determinedly, “My mother told me to be kind to you, Charlotte, if you came.”

“Your mother!” said Charlotte, amazed. “But I don’t know your mother.” In case that sounded rude, as if she meant she would hate to know her, she added less emphatically. “At least I don’t think I do.”

Sarah turned her head and gazed at Charlotte with unmoving eyes. She smiled a little even. “I don’t think she knows you either. She never said that. She just told me that if a girl called Charlotte Makepeace came to school, I was to be kind to her. She’s never told me to be kind to anyone else.”

•

That evening Susannah asked Charlotte to be her best friend. No one had ever asked her this before, and though certain she did not really want to be Susannah’s best friend, she was touched and pleased by it. And she did not know how to refuse without being unkind. In the end, she answered yes, but she was so busy thinking about what Sarah had said to her in the afternoon that she forgot to mention Susannah when she wrote to Clare in the pink-covered exercise book.