HOW STRANGE it was to crouch in the half-dark between heavy table and heavy cupboard, exploring the toys of a generation back, by feel and smell as much as sight. It was absorbing, too, and exciting, also sad, because of the faded worn look they had, but perhaps even more because of their smell, sour and musty, the smell of things left long unused.

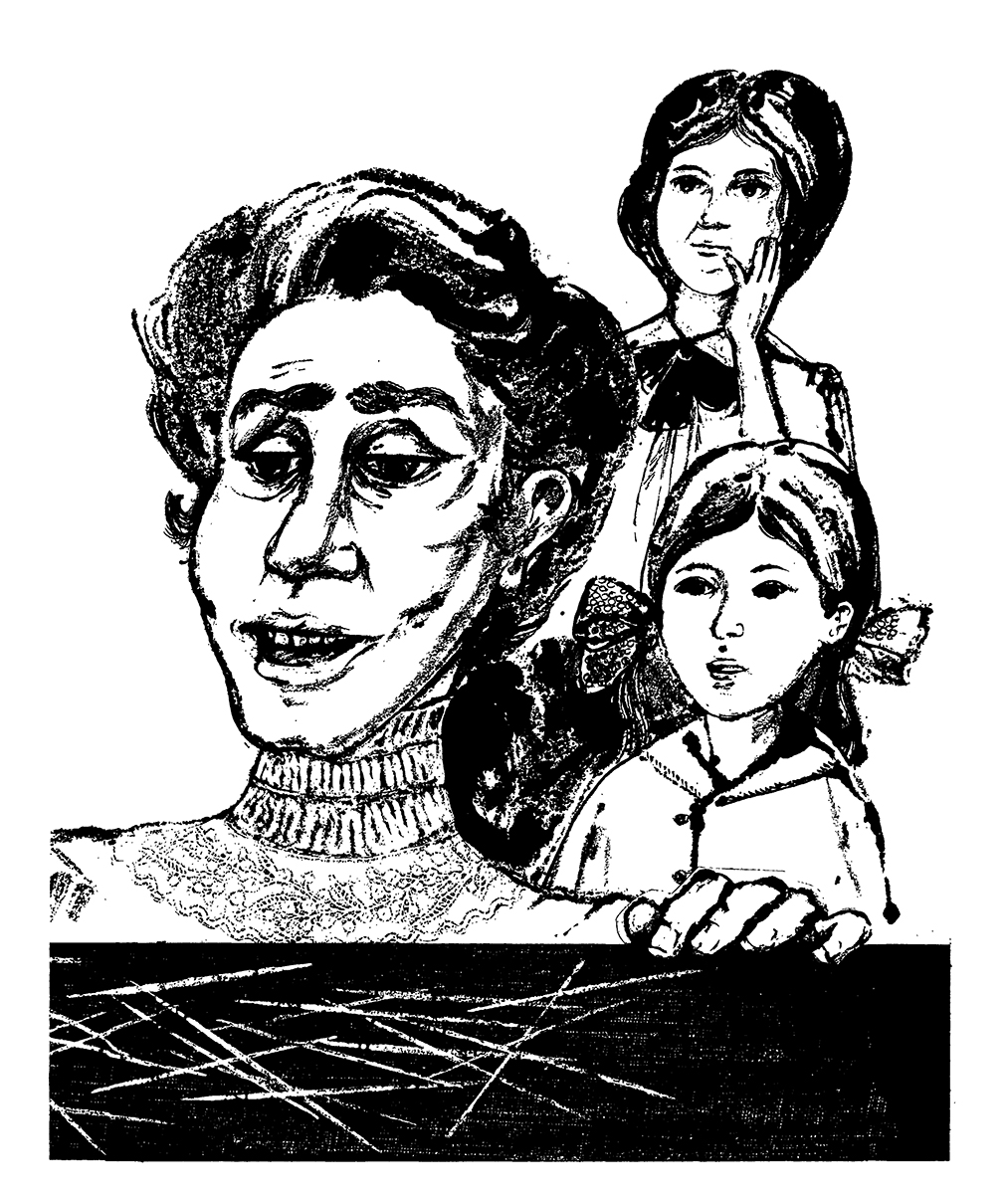

Charlotte examined a package first, one wrapped in tissue paper, which had none of the crispness and whiteness of new paper. It was yellowed, soft as muslin, barely hissing as Charlotte unfolded it carefully, layer on layer, both she and Emily growing more curious toward the parcel’s core, in which, at last, they found a doll. It had a china face, rather chilly to touch, with fat white cheeks and huge, fringed eyes. It had arms and legs of china, too, but the body was soft, covered in thin leather, colder than cloth yet less cold than china for fingers to explore. It wore a blue silk dress, short to the knee and humped a little behind, tied by a pink silk sash, also a hat with a feather in it. It had laced high-heeled boots painted on its legs, and impossibly tiny feet.

“Only a doll, a silly doll. She would have played with dolls, of course, Miss Agnes would, I mean,” said Emily in a disappointed voice.

“Well, what’s wrong with that then? I used to play with dolls, too. And this is such a lovely one.” Charlotte was examining it delightedly, peering to see each tiny perfect detail of stitching and ornament. “We never had any as beautiful as this.”

“Clare did,” said Emily unexpectedly. “She had a doll just like this, only nicer, that belonged to our mother when she was a little girl. It was the only thing we had of hers. She died when I was three, you know, and our father was so sad that he sold everything else, all the furniture and all her old toys and books and things. But he let Clare keep the doll.”

“Didn’t you have anything yourself?” said Charlotte, looking at her, horrified. She could think of nothing more sad than to have nothing at all to remind you of your mother.

“I had my father’s soldiers. He gave them to me specially. He wanted me to play with them. He’d really wanted me to be a boy, you see.”

In spite of this, after a moment Emily held out her hand for the doll, examining it as carefully as Charlotte had done. She began to undress it even, and when Charlotte, opening another box, found an array of soldiers, once bright blue and red but now very rubbed and dented looking, she gave them, at first, only a casual glance while continuing to fiddle with the tiny hooks and buttons on the doll.

Charlotte explored the other boxes, finding all kinds of games: elaborate jigsaw puzzles, a Halma set, checkers in a box made to look like a leather-covered book. Best of all—or so Charlotte thought—in a plain wooden box with a lid that slid in and out, she found a pile of small white sticks most delicately carved.

Emily, by now, had left the doll and was ranging and then rearranging the ranks of scarred tin soldiers on the table beneath the light. She jumped as Miss Agnes’s hands fell gently, tentatively, on her shoulders.

“These were dear Arthur’s soldiers, of course,” she said, making Charlotte jump in her turn. She had not heard Miss Agnes entering because she was so occupied with the small white sticks.

“I didn’t think they were your soldiers,” said Emily cheekily.

“I wasn’t allowed to touch them, of course. Arthur said girls should play with dolls instead. But he played with them all the time, you know. They were his favorite toy.”

“I don’t like dolls, though I’m a girl. I like playing with soldiers best, too, like him.” Emily wriggled a little for Miss Agnes’s hands still rested on her back.

“Whatever are those sticks?” she asked Charlotte. “They look like little baby bones.”

“They’re spillikins. It’s a sort of game.”

“The spillikins! Why, fancy, the spillikins.” Miss Agnes bent forward excitedly. “They’re made of ivory, of course, and that is bone, Emily.”

Charlotte lifted the box of spillikins and poured them out onto the table. They looked less fragile when defined against the dark wood, but just as delicate, barely thicker than little strips of paper. She arranged them as if she was laying a fire, crisscrossing them, save only for one, with a shallow hook on it, that she kept out separately.

“You get the spillikins out with this,” she told Emily. “If you move two by mistake, then someone else has a turn.” She was pleased, warm, off her guard, for they had played spillikins at Aviary Hall, she and Emma and sometimes even their Grandfather Elijah. She was still more pleased when Miss Agnes insisted that they all play spillikins now.

To Emily’s surprise and indignation Miss Agnes won almost every time. She grew quite pleased and fluttery. Pink spots planted themselves in the center of each cheek.

“Of course, dears, I always was good at this,” she said. “I used to beat Arthur every time, and he got so cross sometimes that he’d throw them all on the ground, the naughty boy.”

“Well, I’m good at checkers. I can always beat Clare.” Emily looked at Charlotte pointedly and giggled. She was much too impatient to be good at spillikins, moving them too fast, not wheedling them out by delicate degrees. Charlotte, on the other hand, became absorbed, concentrating wholly on her fingers’ easing, on the slow, light levering of the little strips of bone. There was the moment of suspense when success was near, the relief as she safely flicked a spillikin away, the frustration, contrariwise, when at the last minute fingers lost their control or when one that had seemed an easy win proved so delicately balanced that it set the whole heap twitching at a single touch.

•

The game contracted, expanded seconds, contracted, expanded minutes; made an illusion of no time that lulled Charlotte and comforted her. They might, she thought, have been playing at any time, their minds moving easily from one present to another, from 1918, here, now, to Arthur in the past, to Emma in the future, and also to Clare. This room, she thought, must have looked much the same when Miss Agnes and her brother Arthur were children—the same toys and games were spread about. It might equally have been Aviary Hall as Charlotte knew it, for that had just such dark wood surfaces, just such dowdy light and dim reflections, and saw just such games of spillikins.

Charlotte watched Miss Agnes play, her worn fingers moving patiently, her black brows contracted to a still thicker, blacker line. She felt as if she were suspended between these times, the past, this present, that future of her own, belonging to all and none of them. She looked up half expecting to see Emma there, beside Miss Agnes, or Arthur the boy in the tinted photograph. It surprised her even to find only Emily.

•

That night Miss Agnes said they were to go to the drawing room, where Mr. and Mrs. Chisel-Brown stayed all the day as far as Charlotte and Emily could see, though Miss Agnes worked continually, cooking and organizing the house. On one side of its empty fireplace sat Mr. Chisel-Brown behind his newspaper; on the other, like a fat, white Buddha, sat Mrs. Chisel-Brown behind nothing but her face, which glimmered a little, palely, in the surrounding gloom. The fat, hairy dog lay on her lap; the fat black cat was curled up at her feet. On a table beside her stood a forest of photographs. All were of Arthur, Charlotte thought. At least all seemed to be of a boy or man, though she could not see very well, and it would have been rude to peer.

“Good night,” Charlotte whispered tentatively, for that was what they had come to say.

“Good night,” growled Emily.

“My young day,” observed Mr. Chisel-Brown to his newspaper, “my young day, young people bade good night each company in turn. Of course, have hunnish manners now.”

“That’s right, dear Emily,” Miss Agnes hinted at their backs. “Say good night, Mr. Chisel-Brown, Mrs. Chisel-Brown. Good night (and here she giggled a little), good night, Miss Agnes.”

“Miss Agnes Chisel-Brown,” observed her father fiercely.

“Good night,” said Charlotte, obedient, confused, and suddenly very, very tired. “Good night, Mr. Chisel-Brown, good night, Mrs. Chisel-Brown, good night, Miss Agnes Chisel-Brown.”

Emily said nothing but looked defiantly at Mr. Chisel-Brown, who rose to his feet and took a soldierly stance, fiddling with his moustache.

“Say good night, Emily dear.” Miss Agnes was hinting still.

“Oh please, Emily,” said Charlotte, “say good night.” “Oh please, Emily,” she was thinking, “please say it; it’s so much easier, and I’m so tired.”

Mr. Chisel-Brown stared at them, puffing himself out, swaying a little on his feet, as if to let the wind carry him away. No balloon could have been fuller of air than he.

Emily gave a little smile.

“Good night, Mr. Chisel-Brown,” she said with almost a curtsy. “Good night, Mrs. Chisel-Brown, good night, Miss Agnes Chisel-Brown. Good night, cat. Good night, dog,” she said, and then at once, giggling, fled, out of the drawing room and up the stairs.

Charlotte waited, terrified, her eyes fast to the floor. But nothing happened. Mr. Chisel-Brown deflated himself and returned to his newspaper. Mrs. Chisel-Brown continued to sit as she had sat before. Charlotte, beckoned by Miss Agnes, departed at last to her bed. And when she went to breakfast the next morning, dreading repercussions, Mr. Chisel-Brown just glanced over his newspaper with a kind of a growl, and nothing more was said that morning or any morning.

“Anyone would think,” said Emily triumphantly, “anyone would think he was frightened to tell me off.”