6

WORLD WAR I

1914–1918

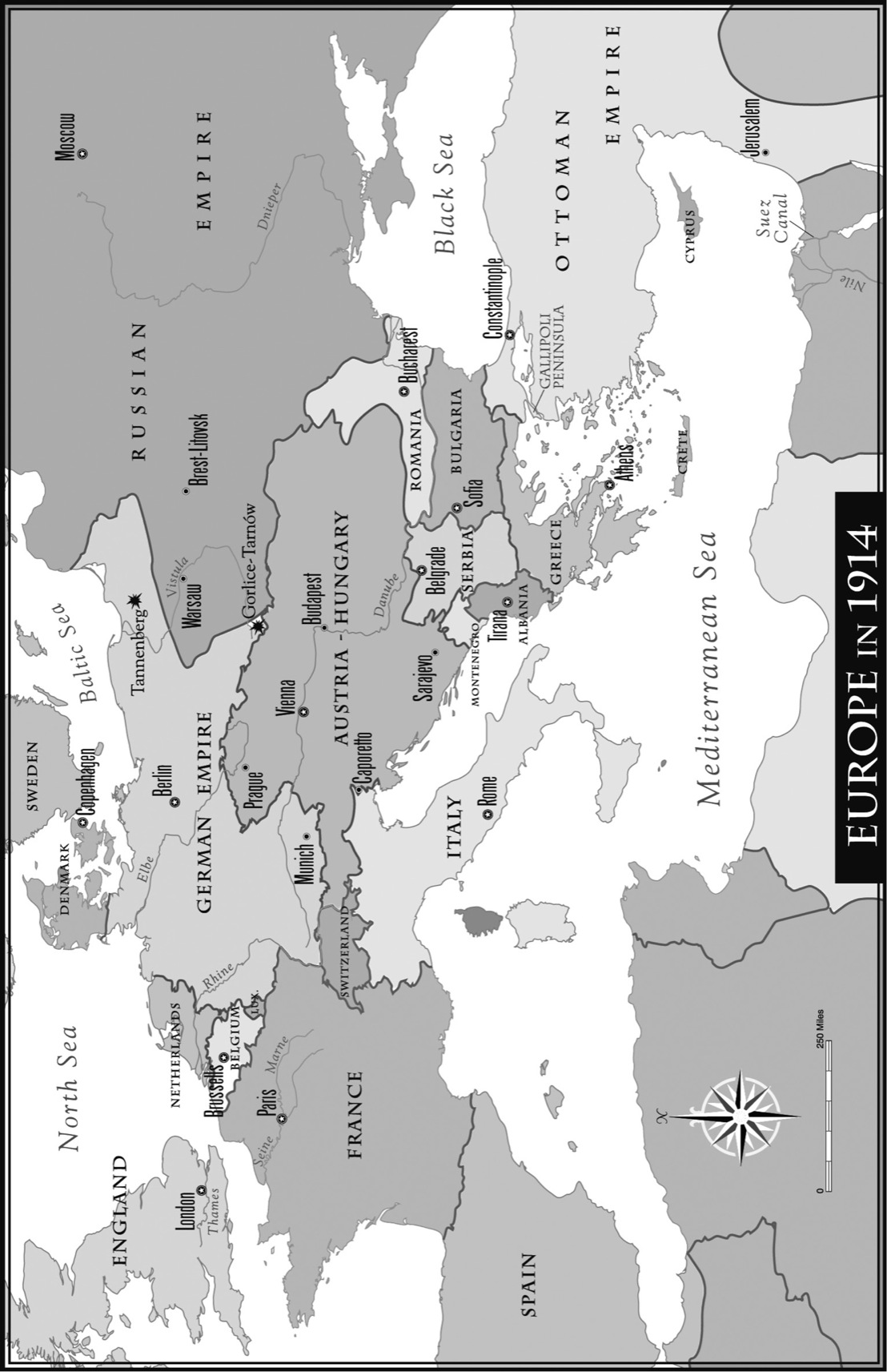

In June 1914, a single act of political murder in Bosnia set in motion a sequence of events that resulted in a war in Europe, a war that soon reached far distant parts of the globe. The impact of this conflict would be devastating to both individuals and nations. More than eight million soldiers would lose their lives. They would die in mud, in the desert, on snow-covered mountains, and at sea. They even would die in the air. In France, 630,000 women would become widows. In Belgium, Serbia, Turkey, and elsewhere innocent civilians, including women and children, would perish, many of them simply executed. Countries too would die, and maps would need to be redrawn. The Austrian-Hungarian Empire of the Hapsburgs would disappear. The German Imperial State would collapse and its kaiser would move to Holland, emperor no longer. The Ottoman Empire, ruler of what is now Turkey and much of the Middle East, would share the fate of the Hapsburgs and cease to exist. The tsar and Romanov rule in Russia would come to a violent end, replaced by the Bolsheviks. America, late to the war, would emerge relatively unscathed, in better shape than all the nations that earlier had sent their young men to fight and die.

The conflict of 1914–1918 was to be a milestone in human history. Nothing like it had ever occurred. Those who lived through it called it the Great War. Today, less aware of its impact, we refer to it simply as World War I.

***

Archduke Franz Ferdinand was the heir to the throne of the Austrian-Hungarian Empire. This was an empire that had seen better days. Comprised of many different nationalities—its subjects spoke twelve different languages—the Austrian-Hungarian state in 1914 was a ramshackle affair, conservative to the core, with an army that was large but not terribly effective. On June 28, their wedding anniversary, Franz Ferdinand and his wife Sophie were in Sarajevo, the capital of Bosnia, which, though part of the empire, contained many Serbs. To the south and adjacent to Bosnia was Serbia, an independent nation many of whose people, then, as now, were prone to violence. The Serbs detested the empire of Austria-Hungary, whose rulers reciprocated the feeling.

Thus, no one was surprised when with the complicity of Serbia, a young Bosnian radical shot and killed the archduke and his wife. Correctly blaming Serbia, the empire, with Germany’s approval, declared war on its southern neighbor. That upset Russia, which, because of race and religion, considered itself the protector of Serbia. Russia mobilized its armed forces. That in turn alarmed Germany, which saw Russia and its vast number of men eligible for military service as a direct threat to its security. Germany then put its armed forces on notice, which in turn made the French extremely nervous. Forty years earlier, France had been invaded by Germany and, defeated in battle, had ceded to the victor the provinces of Alsace and Lorraine. These the French considered theirs, and they hoped someday to regain them. When the German army mobilized, France naturally enough brought its own military to full alert.

In 1914 most military experts believed that in any war the army that attacked first would win. Armies that found themselves on the defensive, these experts predicted, likely would lose. Once mobilization had been ordered, most generals, and certainly those of the kaiser, believed the war in effect had begun. Once Russia had ordered its army to get ready, German generals considered their country at war.

Though formally at peace with one another, the nations comprising Europe in 1914 were highly distrustful of those countries they viewed as adversaries. Competing desires for empire, rivalry in trade and industry, different political traditions and forms of government, as well as armies and navies that planned for war all made Europe a tinderbox ready to explode. The assassination of Franz Ferdinand provided the spark. True, diplomacy could have doused the flame, but it didn’t. The result was that in August 1914, the world went to war, and the killing began.

Geography had not been kind to Germany. To its east lay Russia, to its west France. With good reason, these countries viewed the kaiser’s army with alarm. They had an agreement that if one were attacked, the other would come to its aid. Hence, Germany found itself trapped. Each of the two, so the kaiser believed, sought to deny Germany’s rightful place in Europe and the world. But France and Russia were not the only nations he considered to be holding Germany back. With its huge navy, Great Britain also stood ready to limit Germany’s influence. In response, Imperial Germany, under the guidance of Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz, had built a strong navy. It was not as powerful as Britain’s, but it was a force sufficient to command respect.

German war strategy in 1914 took into account both geography and the armed forces of Russia, France, and Britain. First developed by Alfred von Schlieffen, chief of the German General Staff from 1891 to 1906, its essence was retained by Helmuth von Moltke, who in 1914 was the German army’s commander in chief. Moltke and Schlieffen reasoned that Russia could not mobilize its troops quickly. Germany’s best bet then was to strike first at France and do so with overwhelming strength. The plan was to defeat Germany’s enemy in the west, then, by rail, transport the victorious army to the east, there to confront the Russian horde. The kaiser’s generals estimated that they had forty days in which to beat the French. After that, the Russian menace in the east had to be addressed. Moreover, given that Russia would grow stronger over time, it would be best to strike sooner rather than later.

France too had prepared for war. It had constructed a series of powerful forts along its border with Germany. Any attack there by the kaiser’s troops would run into interlocking fields of fire intended to halt the German advance. But General Joseph Joffre, chief of the French army, wanted to do more than simply hold back the Germans. He wanted his forces to attack. His plan, labeled War Plan XVII, envisioned an offensive into Germany, the goal of which was to retake Alsace and Lorraine.

Aware of the forts and of France’s desire to recover Alsace and Lorraine, Schlieffen had developed an extremely bold plan. The German army would strike not across the border with France. Rather, it would attack from the northwest, through Belgium. The army’s right wing, its most powerful element, would swing wide, crushing both Belgian and French forces, then sweep south to the west of Paris, coming around the city to hit from the rear those French forces that were facing the rest of the German attack.

Though aware that marching through Belgium might bring Great Britain into the war, Germany’s generals were not concerned. The British army was small and not likely to arrive in time. And if it did, it easily could be pushed aside. As to Belgium, its army too was small. The forts on which it relied for defense simply were to be blown to pieces by specially designed heavy guns. Could Moltke and the eight separate field armies he had at his disposal execute von Schlieffen’s plan?

***

On August 4, 1914, German forces crossed into Belgium, heading for France. Two armies were kept home to protect Alsace and Lorraine. Another, the Eighth, was positioned to the east, guarding the nation’s border with Russia. Thus Moltke dispatched five separate German armies to hit the French. Two of them, the First and the Second, constituted the strong right wing of the strike force. Commanded respectively by Generals Alexander von Kluck and Karl von Bulow, they together numbered well over half a million men. It was an impressive force. The kaiser and his army commander in chief believed it was unstoppable.

It was true that Belgium’s army was small, but when King Albert ordered it to oppose the Germans, it did so, and it did so bravely, delaying the German advance.. The results, however, were as the kaiser’s generals had predicted. The forts Belgium had built were destroyed, and those Belgian soldiers not killed or wounded retreated, joining up with the French Fifth Army, which itself was defeated in battle.

Nevertheless, the French commander in chief, true to his desire for offensive action and consistent with War Plan XVII, had sent two armies into Alsace and Lorraine. Attacking along a seventy-five-mile front, the soldiers ran into the two armies Moltke had deployed there. At first the French did well. But by late August they had given way in the face of strong German counterattacks.

By this time, the British too had suffered losses. Once Belgium’s neutrality had been violated by the Germans, the government in London had sent most of the British army to France. What was called the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) began arriving on August 14. It went into action almost immediately. At Mons and Le Cateau, the soldiers of King George V fought hard, inflicted casualties on the Germans, but fell back. At Le Cateau, a small village southeast of Cambrai, the BEF had eight thousand men killed or wounded. Not since Waterloo in 1815 had Britain’s army seen such combat.

So far the Germans had done quite well. They had pushed aside the Belgians, defeated the French, and caused the British to retreat. Closing in on Paris, they reached the Marne River on September 3. That same day the French government abandoned the capital, setting up shop in Bordeaux, far to the south. Soon, German troops crossed the Marne. Some of their heavy guns began shelling Paris. Victory for the kaiser and his generals seemed close at hand.

However, Joseph Joffre did not panic. Calmly, as the Germans advanced, he redeployed his troops (as each day he calmly enjoyed a lengthy lunch, then a nice nap). He also took note of a gap that had opened between the German First and Second Armies. The former, Kluck’s command, had not circled west of Paris. Intent on destroying French forces before him, it had swayed from Schlieffen’s original plan. Paris was on its right flank. To its left, but not close by, was Bulow’s Second Army.

All along a two-hundred-mile front, the battle raged. Defending the French capital, to Kluck’s right, was the French Sixth Army. Among its soldiers were the garrison of Paris. Their commander, General Joseph Gallieni, had requisitioned six hundred Renault taxicabs to transport these troops, five men at a time, to the army. He soon would become known as “the savior of Paris.” His vehicles, the taxies, would pass into legend.

Farther to the east, very much in the fight, Joffre had placed the newly created Ninth Army. Its commander, Ferdinand Foch, had performed well in the defense of Nancy, a major city in northeastern France. In 1918, Foch would play a key role in the Allies’ final victory. He was a capable commander with an aggressive approach to warfare. In the Battle of the Marne, he drafted a signal that, like the Parisian taxis, would become legendary: “My center is giving way, my right is in retreat, situation excellent. I attack.”

The kaiser’s troops fought hard. But they had marched a long way since crossing into Belgium. They were tired and no longer at full strength, having suffered numerous casualties. More important, by early September, they were short of supplies. Logistics—that critical component of both ancient and modern warfare—were to be their undoing. The German army simply could not keep its divisions fighting in France adequately supplied. German units were short of practically everything, particularly food. So the kaiser’s generals were forced to concede defeat. On September 9, the fortieth day, Bulow ordered his Second Army to withdraw. This meant the other German armies had to do the same. The Battle of the Marne was over.

Joffre had won. “The Miracle of the Marne” had saved France. Church bells rang and the nation celebrated. The cost had been high. In the month of September in the year 1914, the French Army had sustained more than 200,000 casualties. October would see that number increase by 80,000. By the end of the year, after but five months of war, 306,000 French soldiers were dead. Twice that many were wounded.

For Germany, the Marne represented its best chance to win the First World War. Unlike in the successful campaign against France in 1870–1871, the kaiser’s armies in 1914 did not crush their opponents or cause a government to topple. Despite successes on individual battlefields, the German efforts in Belgium and France fell short. Yet, though tired and short of supplies, by no means were the German armies a spent force. They retired in good order, retreating to high ground at the Aisne River. There, in addition to emplacing machine guns and siting artillery batteries, they began to dig. So did the French who pursued them. Soon, the trenches that would so characterize the Great War laced the landscape. As winter set in, they would run a distance of 475 miles without a break, extending from the Swiss border to the North Sea.

***

As a result of the German army’s failure at the Marne, Helmuth von Moltke lost his job. His replacement as commander in chief was General Erich von Falkenhayn. By October, given the line of well-defended trenches, the only place where an army might outflank its opponent was to the northwest. The campaign here is often referred to as “the race to the sea.” Falkenhayn focused on a small spot in Belgium still held by the French and British. If he could have success there, he would gain control of those ports nearest to England, thus making operations extremely difficult for the BEF, possibly compelling Great Britain to leave the war. Were that to happen, he would be able to concentrate his armies in the west solely on the French. Despite the outcome at the Marne, Falkenhayn saw in this approach an avenue to victory.

The fighting that resulted lasted for more than five weeks. Falkenhayn’s soldiers fought Belgian, French, and British troops. Collectively, the engagements are recorded as First Ypres, after the medieval town in Belgium around which much of the fighting took place. This first clash was costly to all involved. Together, more than two hundred thousand men were either killed or wounded. In the end, the Germans failed to advance as Falkenhayn had hoped.

For the British, First Ypres would be a memorable battle. Not because they won, which they did, though with heavy casualties, but because it marked the passing of the small, professional army Great Britain had established to fight its battles on land. By the end of 1914, most of the one hundred thousand men comprising that army were gone. They were either dead or wounded. From 1915 on, the British army would have to rely on volunteers and conscripts, young men with little training whose military skills would take time to develop.

If First Ypres left a mark on the British—and it did—it left a mark as well on the Germans. In pushing forward on the attack, Falkenhayn’s forces included a large number of university students who, eagerly, had volunteered for the army. Hastily, they were given uniforms and rifles and, with little preparation, were rushed into battle. The results were catastrophic. Approximately twenty-five thousand were killed. In Germany, their deaths became known as Kindermord, the Massacre of the Innocents. John Keegan, a highly regarded military historian, notes in his fine book on World War I that the insignia of every German university is displayed at the cemetery where the twenty-five thousand are buried in a mass grave.

Holding off the Germans at First Ypres meant that the British and French retained control of a small slice of Belgium. The rest of that country was occupied by the kaiser’s forces. These troops, with the approval of senior army commanders, acted with extreme cruelty toward Belgian civilians. They simply took many of them away and shot them. Additionally, they looted and wantonly burned buildings. This barbaric behavior included the destruction of the ancient university town of Louvain with its unique library that housed irreplaceable medieval and Renaissance works of art. What became known as “the Rape of Belgium” appalled thoughtful people throughout the world. It served to inflame British public opinion, which helped sustain Britain’s commitment to battle. It also contributed to a belief in the United States that Germany did not deserve to win the war.

Both Moltke and Falkenhayn had concentrated Germany’s forces in the west, hoping to defeat France before Russia was capable of waging war. But the tsar mobilized his troops more quickly than expected. Two Russian armies soon attacked, crossing into East Prussia in mid-August. Defending Germany was a single army, the Eighth. Its commander was a retired soldier brought back to active duty, Count Paul von Hindenburg. His chief of staff was General Erich Ludendorff. Together they made a formidable team. In late August 1914, they crushed the Russians at Tannenberg. One of the Russian armies was completely destroyed. Mortified by the totality of his defeat, its commander wandered off into the woods and shot himself. Casualties were high, but the most notable statistic is the number of Russians captured. At Tannenberg, the German Eighth Army took ninety thousand prisoners! The battle was one of the great engagements of the First World War. Germany’s victory was complete. Hindenburg became a national hero. Later on, when Falkenhayn was dismissed, the kaiser appointed Hindenburg as the army’s commander in chief. Ludendorff became chief military planner. As the war progressed, Hindenburg became more of a figurehead, while Ludendorff decided where and when German troops would fight.

For the next three years, 1915–1917, the Germans and the Russians would do battle. Most of the time the Germans won. In 1915 the kaiser’s generals scored a huge victory near the towns of Tarnow and Gorlice in what is now Poland (at that time there were Poles, but no independent nation of Poland, the territory being part of the tsar’s empire). What is remarkable today is the scale of the battles. Thousands upon thousands of men fought and died. In the campaign of Tarnow-Gorlice, the Russian army suffered nearly one million casualties. In pushing the Russians out of Poland, the Germans took 750,000 prisoners. In 1916, in a rare Russian victory over both German and Austrian troops, General Alexei Brusilov’s offensive inflicted 600,000 casualties on the enemy. In the Caucasus, where the Ottoman and Russian Empires collided, the Turks lost more than 60,000 men in an unsuccessful attack on the Russians.

Despite occasional successes, the war did not go well for Russia. Military defeat in the field and political unrest at home led to revolution. On March 15, 1917, the tsar abdicated (and later was executed). The liberal socialist Alexander Kerensky and his government were also toppled (although he was not killed). Vladimir Lenin and the Bolsheviks took control and at once secured an armistice with Germany. The kaiser and his generals were in no mood for leniency. At Brest-Litovsk they laid down harsh terms. The Russians had no choice but to accept. Huge amounts of once-Russian territory were transferred to German control, including what is now Poland, Ukraine, the Baltic states, and Finland. One-third of Russia’s agricultural land was lost. Nine percent of its coal reserves were gone. The result of failure in battle, the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk humiliated Russia. Far more than territory had been sacrificed. By the end of 1917, nearly five million Russian soldiers had been wounded; 1,800,000 were dead.

As the Russians were crushed by the Germans, so too were the Romanians. In 1916, emboldened by General Brusilov’s initial successes and hoping to gain additional territory once Germany was defeated, Romania went to war. Siding with Great Britain, France, and Russia (the Triple Entente), Romanian forces attacked west, advancing fifty miles into Transylvania, then an area belonging to the Austrian-Hungarian Empire, but in which a large number of Romanians resided. Germany’s response was prompt and forceful. One German army, which included troops from Bulgaria and Austria, crossed into Romania from the south along the coast. Another attacked from the north. Together they disposed of Romania’s army as well as Russian regiments sent to help. Victorious German infantry entered Bucharest, the capital of Romania, on December 6, 1916. An armistice soon followed, then a treaty of peace. As with Brest-Litovsk, the terms were harsh. Romania possessed four assets: oil, grain, railroads, and part of the Danube. The Germans took control of all four. Romania in effect became a vassal state. However, it would have the last laugh. At Versailles in 1919, in the treaties that formally concluded the First World War, Romania, having chosen the winning side, was rewarded with Transylvania. Even today the region constitutes the northern portion of the country.

***

Throughout World War I Germany’s principal allies were the Austrian-Hungarian Empire and the empire of the Ottomans. The latter was quite large, covering what is today Turkey, Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, Israel, Jordan, and parts of Saudi Arabia (Egypt and Kuwait were British protectorates). Because the empire was in decline, its army needed assistance. This the Germans provided. Indeed, during the last years of the war, the commander of most Turkish forces in Palestine was Erich von Falkenhayn. Among troops at his disposal were eighteen thousand German and Austrian soldiers. In 1916 General Falkenhayn had led one of the German armies in Romania. By 1917 he was in the Middle East. There he had less success. Earlier, British troops had repulsed a Turkish assault on the Suez Canal and retaken Baghdad, the city having surrendered in April 1916. In 1917, Falkenhayn’s task was to hold on to Palestine. But in a series of engagements with the British, he was unable to do so. Edmund Allenby, the British commander, defeated the Turks and his German counterpart and on December 11, 1917, entered Jerusalem in triumph.

Of considerable assistance to Allenby were a large number of Arab warriors who had little love for their Turkish rulers. A British intelligence officer, T. E. Lawrence, helped convince them to aid Allenby. They did so in part due to British promises of independence once the war ended. Of course, the British had no intention of honoring these promises, as the Arabs discovered at Versailles.

Like the army of the Ottomans, the army of the Austrian-Hungarian Empire required German assistance. The Hapsburg army was large and certainly not lacking in courage. But in early battles with the Russians along their common border, the army was worn down. By the end of 1914, just months into the war, it had incurred 1,200,000 casualties. Twelve weeks into 1915 saw that number increase by 800,000. Many of these soldiers constituted the core capability of the army and could not be replaced. As the war continued, their absence was felt. The empire’s army, while still large, was not effective. It needed help. This came from Germany in the form of men and supplies. In fact, German generals essentially took over command of their ally’s army. More than one German commander said that the kaiser’s army, to use the phrase highlighted by noted historian Hew Strachan, was “shackled to a corpse.”

If there was one nation on which the Austrian-Hungarian Empire wished to wreak havoc, it was Serbia. Since June 1914, revenge for the assassination of Franz Ferdinand was never far from the minds of the Hapsburg leaders. Very early in the war, the Austrian-Hungarians attacked. Remarkably, the Serbs held them off. Despite the setbacks and 227,000 casualties, the Austrians had no intention of quitting. They turned to the Germans and to the Bulgarians, and in the fall of 1915, troops from all three countries invaded Serbia. They were under the command of one of Germany’s better generals, August von Mackensen. He had won the great victory at Tarnow-Gorlice and in 1916 would lead one of the German armies into Romania. His efforts in 1915 soon had the Serbs in full retreat. The defenders fought hard, suffering ninety-four thousand casualties. But their opponent was too strong and Serbia’s army and government had to flee. Their epic march across Montenegro and Kosovo to the Adriatic Sea, where Allied ships took them off, is today part of Serbian legend.

The soldiers of Austria-Hungary fought not only the Serbs and the Russians, they also fought the Italians. Italy and the Austrian-Hungarian Empire shared a four-hundred-mile border. This was mostly mountains, which favored those waging a defensive battle. Nevertheless, and to their great credit, the Italians attacked, fighting along the Isonzo River (a river near the northeastern corner of the Italian Republic that flows into the Gulf of Trieste). Indeed, in the years 1914 through 1917, they attacked eleven times. For their efforts, however, they gained little ground, while absorbing substantial casualties. Here again, the scale of military operations in the First World War is evident. The total number of men wounded or killed in 1915 in combat between two second-tier states—Italy and Austria-Hungary—on a battlefront considered primary by neither the British, the French, nor the German commanders was slightly more than 424,000.

The number of casualties would increase. In the eleventh battle along the river in August 1917, the Italians suffered an additional 155,000. This time, they made significant gains, so much so that Austria-Hungary, alarmed, requested assistance from Germany.

Germany gathered together several infantry divisions and, with troops from the Austrian-Hungarian Empire, established a new army that attacked the Italians in October 1917. In but a few weeks its troops achieved a great victory, driving the Italians back a distance of some sixty miles. This, the Battle of Caporetto, remains a painful memory for Italy and its army. Ten thousand Italian soldiers were killed and three times that number were wounded. Almost unbelievably—and another indicator of the scale of the 1914–1918 conflict—German troops took 275,000 Italians prisoner. Yet the Italian army recovered. A year later it went on the offensive, supported by British, French, and American units. It fought well and, across a wide front, pushed the Austrians back. This success, achieved right at the end of the war, earned Italy a seat at the head table when at Versailles the Allies redrew the map of Europe. As did Romania, Italy came away with additional territory that remains part of the country today.

Serbia, Romania, the Italian Alps and the Caucasus, Bulgaria, and Palestine are all places far from the trenches of Western Europe. For most Americans, it is these trenches that have come to symbolize the First World War. Yet in each location just mentioned, generals issued orders, soldiers obeyed, and men died. But there are two other places not usually associated with the conflict of 1914–1918 that saw military operations during the Great War. These are Africa and China. Both witnessed the clash of arms.

In 1914 Imperial Germany had an outpost on the northern coast of China, at Tsingtao. Eager to expand its influence and believing Germany to be otherwise occupied, Japan, with Britain’s concurrence, landed sixty thousand troops nearby and, in early November 1914, took control of the city. During the same period, Japan also seized German outposts on the Caroline and Marshall Islands. None of this came as a surprise to the generals and admirals in Berlin, because Japan had declared war on Germany months before, on August 23. In addition to outposts in China and the Pacific islands, Germany also had a presence in Africa. So did other European powers, most notably Britain, France, and Belgium. Germany controlled what is today Togo and parts of Cameroon, Ghana, Tanzania, and Namibia. In all these locations British and German forces went to war, with both sides employing mostly native soldiers (the French brought their African troops north and employed them in the trenches, where no doubt the rain and cold came as quite a shock). Eventually, the British carried the day, although in German East Africa one hundred thousand British troops were unable to decisively defeat fifteen thousand irregulars of the enemy. The latter were led rather brilliantly by the German Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck, who both during and after the war was a national hero.

***

Lettow-Vorbeck never had to deal with trench warfare, where barbed wire, heavy artillery, aerial observation, and machine gun nests made both attacking and defending a hazardous occupation. Joffre and Falkenhayn did, as did Sir John French, the commander of the BEF. In 1915, all three went on the offensive. The result for each of them was failure. Their armies gained very little ground but suffered substantial casualties. 1915 was a year of slaughter.

The French, in particular, took heavy losses. In the autumn, attacks alone in Joffre’s army had 190,000 soldiers killed or wounded. At Loos, in September 1915, the BEF saw 16,000 of its men dead with another 25,000 wounded. Four months before, at the Second Battle of Ypres, a German assault also resulted in numerous casualties. The Germans, who again failed to push the British out of the city, suffered 38,000 casualties. What makes the Second Battle of Ypres particularly noteworthy is that Falkenhayn’s forces began their attack by employing chlorine gas. The British responded in kind at Loos. As the war continued, gas remained one of the available weapons, although it did not prove decisive.

The inability of the French and the British to achieve success on the Western Front late in 1914 and early in 1915 led to a decision to seek victory elsewhere. They decided on Gallipoli, a peninsula jutting down from Istanbul adjacent to the Dardanelles, the body of water that links the Black Sea with the Mediterranean Sea and which separates the continents of Europe and Asia. Success at Gallipoli would relieve pressure on the Russians and might well compel the Ottoman Empire to withdraw from the war. It also would boost the morale of the folks back home, who by now had noticed that despite huge loss of life, victory was nowhere in sight.

At first British and French warships attempted to force their way through to Istanbul. That did not work, so the British landed troops ashore in the largest amphibious operation of the war. Among these troops were Australians and New Zealanders. They were known as the ANZACS (the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps) and their exploits at Gallipoli would win them great fame. However, they suffered some 10,000 casualties, for them a substantial number but a small percentage of the 265,000 Allied troops killed or wounded in an expedition that failed. When the British withdrew in December, no one in the British army or government thought the effort had been other than a debacle.

As the British were departing from Gallipoli, Joffre and the new commander of the BEF, Sir Douglas Haig, were planning their campaigns for 1916. The French general believed in offensive maneuvers and in the imperative of removing German soldiers from French soil. Haig believed the only way to win the war was through attrition, engage the German army in battle, defeat it, and do battle again. Their plans for 1916 envisioned a series of strikes, straight at and through well-entrenched German positions.

However, Erich von Falkenhayn struck first, preempting Joffre’s attacks. In late February, following a massive artillery barrage, the German general sent his troops forward. Their objective was Verdun, a town on the Meuse River some 150 miles northeast of Paris, a town Falkenhayn knew the French would be unwilling to lose. So began the longest single battle of the First World War. When it was over, 162,440 French soldiers were dead. The number of Germans killed was slightly less. Falkenhayn had hoped to so wear down the French army as to render it ineffective. He came close. But the French commander in charge, Philippe Pétain, one of the few French generals committed to defensive warfare, led his soldiers calmly and courageously and held Verdun. He earned, as Joffre had at the Marne, the reputation of saving France. Given the battle’s outcome, Falkenhayn was relieved of command. His failure at Verdun instead had worn down the German army.

If, as it is by many, the First World War is seen as a bloodbath of the first rank, the Battle of Verdun is one reason. Another is the Somme.

One hundred and fifty miles long, the River Somme flows through Amiens into the English Channel. The battle to which the river gave its name began in July 1916 and lasted five months. Haig, a general whom history has not treated well, planned meticulously. His attack was to be preceded by the heaviest artillery barrage the British army could muster: one field gun every twenty yards across a sixteen-mile front. This was intended to destroy the barbed wire and machine gun emplacements the enemy were known to have deployed, as well as kill any Germans unfortunate enough to be in range. As the British infantry advanced, their supporting artillery was to move forward, providing covering fire. It was to be a creeping barrage.

The plan was sound. Its execution was not. The British artillery failed in its task. There were too few guns, they were too small in caliber, there were too many shells that did not explode, and there was too much mud. Moreover, the kaiser’s soldiers proved remarkably resilient. For Haig’s troops, the results were catastrophic. That first day, July 1, 1916, 19,240 British soldiers were killed. That number needs to be repeated: 19,240 British soldiers died on the first day of the Somme. Total casualties that day numbered 57,470. The battle continued for another forty days. Losses piled up, for the Germans as well and for the French, whose Sixth Army was part of Haig’s force.

When the battle came to a close—it’s official end is deemed November 18, 1916—the butcher’s bill was staggering. Great Britain’s official history of the war states that the combined casualties of the British and French forces totaled 623,907. Of this number the British owned 419,654. All for a negligible gain in territory. German losses are more difficult to ascertain, but certainly numbered near to those of their enemy. As John Keegan has written of the British army, the Somme “was, and would remain their greatest military tragedy of the twentieth century, indeed of their national military history.”

Yet it must be recorded that the Somme was a victory for the British. Not due to territory gained, a mere three miles that in no way altered the strategic picture, but because having themselves suffered horrendous losses, the German army retreated, withdrawing up to forty miles in some places. They then completed a system of strong defensive positions which the British dubbed the Hindenburg Line. Once there, the kaiser’s army, now with Hindenburg and Ludendorff in charge, planned no major offensive. The Somme, wrote an officer on the German General Staff, had been “the muddy grave of the German field army.”

While the German commanders were content to remain on the defensive, their counterparts in the French and British armies were not. For them and their troops, 1917 would be a difficult year.

The heavy losses at Verdun had spelled the end of Joffre’s tenure as commander in chief of the French army. He was replaced by General Robert Nivelle. An expert in artillery, Nivelle had performed well at Verdun. In 1917, he persuaded the French government that he had battlefield tactics that would bring success against the Germans. He did not. In fact, his tactics were more of the same: massive artillery strikes across a narrow front followed by infantry and continuous, rolling cannon fire. Nivelle’s offensive began on April 16, 1917. It lasted just five days. The French army got nowhere, but incurred 130,000 casualties. Nivelle and his offensive were disasters. The result was a broken army. More than a few units refused to do further battle. These were the famous mutinies that inflicted the French army in the middle of 1917. Pétain was ordered to replace Nivelle, and by improving the lot of the ordinary poilu, and by not, for a while, engaging in offensive actions, he was able to restore both discipline and morale. He also had 629 soldiers condemned to death, but executed only 43.

The British army too went on the offensive in 1917, several times. Embracing the strategy of attrition Haig wanted his troops to attack, and attack they did. The first assault occurred at Arras and began on April 9. At first, the British troops did well, taking 9,000 prisoners and suffering few losses. But, as happened so often in the First World War, the attack stalled, the Germans struck back, and a slugging match became a stalemate. In the end, the British listed 150,000 men as casualties.

Taking part in the Battle of Arras were four Canadian divisions, some eighty thousand men, operating for the first time as the Canadian Corps. Their attack on Vimy Ridge was successful, earning well-deserved fame for Canada and its soldiers. For the action at Vimy Ridge, the Canadian Corps’s commander, Major General Arthur Currie, was knighted on the battlefield by King George V.

The second British offensive of 1917 took place at Ypres, the third time this city and its environs became a battlefield. Its objective was to secure the coast of Belgium, thereby denying submarine bases to the German navy. The attack began with 2,229 pieces of artillery opening fire, ten times the number employed at the Somme. The infantry went “over the top” at 3:50 A.M. on July 31. As with Nivelle’s offensive, the outcome was disastrous. After four months, seventy thousand British soldiers were dead. What made the attack fail was the pervasive rain and mud. And, of course, German resistance. Keegan calls the battle “the most notorious land campaign of the war.” The battle often goes by the name Passchendaele, a small village outside of Ypres that marked the farthest advance of Haig’s army.

The British commander believed the Germans were suffering as much as his army and could less afford the losses. So Sir Douglas attacked again. This, the third British offensive of 1917, took place at Cambrai, a city northeast of Paris, not too far from the border with Belgium. The results followed a familiar pattern: initial success but little gain once the Germans counterattacked. What makes Cambrai significant in military terms is that, for the first time, massed formations of tanks were used. Though slow and prone to mechanical failure, these machines at Cambrai ushered in a new era of land warfare.

***

During 1917, Hindenburg and Ludendorff, Nivelle and Pétain, and Douglas Haig commanded troops that engaged in battle, in titanic struggles that help define the First World War. Yet 1917 also witnessed two events that marked the beginning of the end of the great conflict. One such event took place in Washington, D.C., in April. The other occurred in Berlin.

On January 9, 1917, at its capital Germany announced its intention to renew unrestricted submarine warfare. “Unrestricted” meant that no longer would a German unterseeboote, or U-boat, refrain from sinking neutral vessels or allow time for crew to disembark from a ship about to be torpedoed. Beginning in February, any ship would be sunk on sight. Many people were shocked by this announcement. What the Germans were about to do was considered uncivilized, unnecessarily cruel. But the commanders in Berlin understood that war requires harsh behavior, and besides, submarines had little room for displaced sailors. Moreover, the kaiser’s admirals, and his generals as well, understood that after several years of conflict, such U-boat strikes offered the best chance of winning the war. The goal was to force Britain to withdraw from the war, by depriving the island nation of food and essential materials. If Britain were to opt out, France, then alone, could be defeated. This goal had to be achieved before the United States entered the war, which it was likely to do once the U-boats began their campaign. When America joined forces with France and Britain, the battlefield equation would be altered and Germany would lose the war.

Of course, the war at sea had begun well before 1917.

When the German East Asiatic squadron had to abandon Tsingtao late in 1914, most of its ships sailed across the Pacific Ocean to the coast of Chile. There, under the command of Maximilian von Spee, they destroyed two Royal Navy cruisers, killing sixteen hundred British sailors. In London the Admiralty promptly dispatched three battle cruisers, among them the Invincible and the Inflexible, to deal with the Germans. This they did, totally destroying Spee’s squadron in December.

In 1914 Britain may have had a small army, but it possessed a large navy, one which, if it did not rule the waves, came very close to doing so. Upon the declaration of war, the Royal Navy instituted a blockade of Germany. Writing in 1930, Captain B. H. Liddell Hart, a noted military historian, said the blockade “was to do more than any other factor towards winning the war for the Allies.” The navy’s blockade effectively cut off seaborne traffic to and out of German ports. In time, the blockade imposed severe hardship on the country’s industry and civilian population. By 1917, food shortages were causing great distress. By mid-1918, the situation in German cities was such that social unrest was unraveling the political cohesion of the Imperial German state.

With its many warships, Britain hoped to lure the kaiser’s quite capable surface fleet into battle. This, it was expected, would result in a great victory, as Trafalgar had been in 1805. In command of the Royal Navy’s powerful fleet was Admiral Sir John Jellicoe. On May 31, 1916, he had his chance. The two fleets slugged it out in the North Sea, some fifty miles off the Jutland Peninsula. The statistical results favored the Germans. They lost eleven ships and 3,058 sailors. Jellicoe (about whom Winston Churchill said he was the only man in England able to lose the war in an afternoon) had fourteen ships sunk and twice that number of men killed. But the battle did not alter the strategic picture. Afterward, the Royal Navy still controlled the seas. Germany’s fleet returned to port. Never again did it challenge Britain’s maritime preeminence.

Only U-boats could, and would, do that.

German submarines registered their first kill early in the war. On October 20, 1914, U-17 sunk the Glitra, a small British ship sailing near Norway. Thereafter, the tempo of attacks quickened. The shipping lanes around the British Isles became dangerous places. On May 7, 1915, in waters close to Ireland, a German submarine put a single torpedo into the starboard side of the Cunard liner Lusitania, which then took but eighteen minutes to sink. The ship was carrying artillery ammunition for the British army and, thus, was a legitimate target for U-20. Of the 1,195 fatalities, 123 were American. People in the United States, already angry with Germany over “the Rape of Belgium,” were outraged. When months later, more U.S. citizens were killed in a submarine attack, President Woodrow Wilson sent an ultimatum to Berlin: halt unrestricted submarine warfare or the United States would sever diplomatic relations with Germany and, in essence, enter the war on the side of France and Britain. Surprisingly, the Germans did so. But by 1917 the situation was such that the German High Command reinstated the policy. That year the kaiser’s navy had 111 U-boats in service. Their commanders, armed with skill and courage as well as torpedoes, intended to destroy the maritime lifeline on which Great Britain depended. As the number of ships sunk increased, it looked like they would succeed.

Senior officials in London became alarmed. Among them was Jellicoe, who in June 1917 declared that Britain had lost control of the seas. By then first sea lord, the top position in the Royal Navy, Jellicoe told his colleagues that Britain would not be able to continue to fight in 1918. Needless to say, this message sent shock waves through the British government. Such pessimism could not be tolerated. Jellicoe was sacked. More important, the navy changed its method of combating submarines.

At first, merchant ships sailed singly. Proposals to group them in an assembly of vessels, a convoy, escorted by naval vessels were rejected. The rationale was that a group of ships would be easier for a U-boat to spot and would overload the capacity of British ports upon reaching its destination. However, both analysis and experience eventually showed the rationale to be flawed. Ports could handle the influx of ships. Moreover, the ocean is so large that a submarine is no more likely to find forty ships than it is to find one. And because the convoy would have Royal Navy ships on guard, success by the U-boats would be limited.

Belatedly, Britain’s navy therefore required merchant ships to sail in convoy. This produced the intended result. More and more ships arrived safely. April 1918 was the turning point. From then on, Britain received the supplies needed to continue the war effort.

There was a second failure on the part of the kaiser’s submarines, one that receives less attention than it deserves. They failed to prevent the transport of American soldiers to France. More than two million “doughboys” crossed the Atlantic to serve in the American Expeditionary Force (AEF). All went by ship. Not one U.S. vessel was sunk. However, what the German submarine campaign did accomplish was America’s entry into the war. On April 6, 1917, in Washington, D.C., the United States declared war on Germany.

The United States entered the conflict to save democracy. Added Woodrow Wilson in requesting the declaration:

We desire no conquest, no dominion. We seek no indemnities for ourselves, no material compensation for the sacrifices we shall freely make. We are but one of the champions of mankind.

For Wilson, the enemy was German militarism. America was to join Britain and France, themselves democratic states, and rid the world of a government that held in contempt both freedom and justice. Allied propaganda helped sway the Americans and their president. It portrayed the Germans as barbarians, a description seemingly verified by their behavior in Belgium and by their approach to submarine warfare.

Americans were outraged by the sinking of ships without warning, particularly ships carrying U.S. citizens. They also were outraged by Germany’s foolish effort to tempt Mexico into the war. Alfred Zimmermann was the kaiser’s foreign minister. Early in January 1917 he sent a coded message to the German ambassador in Mexico suggesting that in the event of war between the United States and Germany, Mexico side with the latter. Upon the war’s conclusion (with Germany victorious) Mexico would be rewarded with Texas and other lands it had once possessed. The British intelligence service intercepted the message and passed it on to the U.S. Department of State. Neither Wilson nor the American people took kindly to Zimmermann’s intrigue. The result simply was another reason to go to war.

Wilson, who in 1916 had campaigned for reelection by proclaiming that he had kept America out of the war, had one additional reason for having the United States enter the conflict. As historian Hew Strachan has pointed out, President Wilson understood that if America were to participate in designing the postwar world, it would have to do some of the fighting. And Woodrow Wilson wanted very much to craft that future world. Indeed, he had at least fourteen ideas as to how to do it.

***

Both then and now, the army the United States deployed to France in 1917 and 1918 was called the American Expeditionary Force. The AEF’s commander was General John J. Pershing.

Known as “Black Jack” because he once had commanded African-American soldiers, Pershing was a combat veteran of the war with Spain and of the insurrection in the Philippines. In 1916, he led an expedition into Mexico in search of Pancho Villa, who had raided several towns in the United States. Pershing was a tough, demanding officer respected by his men but not beloved. His career, no doubt, had been helped by having a father-in-law who was chairman of the Senate’s Military Affairs Committee.

Arriving in France in June 1917 (it was an aide to Pershing not the general who said, “Lafayette, we are here”), Pershing had to assemble, supply, and train a force capable of taking on the kaiser’s battle-tested army. This was no simple task, for the Americans getting off the ships were neither well prepared nor properly equipped. The AEF had no artillery, no tanks, no airplanes, and no machine guns. The men themselves were little more than raw recruits. Many had never fired their weapons. To turn them into a combat-ready army required time and instruction. It also required equipment, much of which was purchased from the French. Pershing was able to buy what he needed. The AEF bought 3,532 artillery pieces, 40,884 automatic weapons, 227 tanks, and 4,874 aircraft from French suppliers. When the Americans finally went into battle, they did so because French manufacturers had provided much of their equipment.

Training also was provided by the French, as well as by the British. Veterans of combat, these instructors taught the Americans how to survive and fight in the hellish world of trenches, barbed wire, mud, poison gas, machine guns, and deadly artillery fire.

Pershing himself wanted the Americans to emphasize the rifle and the bayonet. His war-fighting doctrine stressed marksmanship and maneuver. He envisioned the AEF making quick frontal assaults, then breaking through German defenses and advancing rapidly, destroying the enemy as it moved forward. That this approach made little sense in the environment of the Western Front appeared not to register with General Pershing. It certainly made an impact on the average American soldier. Many of them died or were wounded needlessly. The consensus seems to be that the number of casualties suffered by the AEF—255,970—was larger than it should have been.

By war’s end the American Expeditionary Force had grown to just over two million men. In total, the United States Army numbered 3,680,458. This was a staggering increase over the 208,034 that constituted the army in early 1917, at which point the American army ranked worldwide sixteenth in size, just behind Portugal.

Transporting the AEF to France was no easy task. It was done by ship, of course, and took time. More than one senior official in London and Paris wondered whether the Americans were ever to arrive. True, at first the buildup was slow, but by the summer of 1918, fourteen months after Congress declared war, U.S. troops were pouring into France.

French and British generals wanted the arriving soldiers to be allocated to their armies. The Yanks were to replenish Allied regiments depleted by three years of warfare. The generals reasoned that the Americans not only lacked combat experience, they also lacked staff organization essential to large military units. Developing these staffs, gaining the necessary experience, would take time, valuable time. Better, they argued, to place the Americans among experienced French and British troops, and do so right away. Waiting for a fully prepared, independent U.S. Army risked defeat on the battlefield. Time was of the essence. The best way to utilize American soldiers was to distribute them among seasoned troops already on the front line.

Pershing said no. Though directed by the secretary of war to cooperate with the French and the British, the commander of the AEF had been ordered to field an independent American army and to lead it into battle. This is exactly what he did.

Senior French and British generals, several of whom thought Pershing was not up to his job, frequently tried to have the American troops amalgamated into their armies. And, just as frequently, Black Jack replied that Americans had come to France to fight as an American army, pointing out, probably correctly, that U.S. soldiers likely were to fight more effectively under American officers in an army whose flag was the Stars and Stripes.

Yet, to Pershing’s credit, when in May–June 1918 a battlefield crisis arose and both General Ferdinand Foch and Field Marshal Sir Douglas Haig urgently needed additional troops, Pershing dispatched several U.S. divisions to bolster French and British forces.

The principal fighting unit of the AEF was the division. At twenty-eight thousand men, it was twice the size of British and French counterparts. All forty-three divisions that served in France were infantry divisions. While an AEF division would have its own artillery and support units—plus 6,638 horses and mules—its principal component was the rifleman. The United States entered the war deficient in modern weaponry. As previously noted, the AEF lacked artillery, aircraft, tanks, and machine guns. What it did possess, and what it did contribute, was manpower. By the summer of 1918, the French army was worn out. The British army, still ready for battle, was running out of men. Pershing’s army represented a vast influx of men, men whose number and willingness to fight would play a decisive role in the outcome of the First World War.

Two of the forty-three divisions of the AEF were composed of black Americans. These were newly raised units, the 93rd and 92nd Divisions. The former was loaned to the French army and fought extremely well. One of the 93rd’s regiments, the 369th “Black Rattlers,” served with great distinction. The 92nd had less success. It remained in the AEF and went into battle in September. Due mostly to poor leadership and incomplete training, the division performed poorly. This, unfortunately, left a legacy in the American army. Throughout the postwar years, the army’s officer corps were skeptical of the ability of African-Americans to both command and fight.

Racism was alive and well in America during the years of the First World War. This permeated the nation’s army, wherein blacks usually were given jobs of secondary importance. In 1916 there were four “colored” regiments in the regular army. None of them served in France. However, some two hundred thousand other African-American soldiers were part of the American Expeditionary Force. Yet most of these men were put to work in what essentially were labor battalions, digging ditches and unloading ships. This, despite the fact that U.S. authorities had established an officer training school for blacks in Des Moines, Iowa, that produced more than eleven hundred officers for the United States Army.

Women too faced discrimination in the army. Given that in 1917–1918 they did not have the right to vote, this is not surprising. About ten thousand women served as nurses in the AEF. Though treated as officers, they were not paid as such. Nor, according to historian Byron Farwell, did the army provide them with uniforms or equipment. Those came from the Red Cross. Despite the inequity, the women’s services were indispensable and performed with skill and dedication.

Also performing essential medical services were Americans who, prior to the United States’ entry into the war, drove ambulances for the French military. They were volunteers, many of them students or graduates of America’s finest colleges. Serving as noncombatants, they transported wounded French soldiers from the battlefield to the hospital. More than two thousand young men so volunteered, eventually carrying some four hundred thousand soldiers to safety.

Nurses were not the only group of women attached to the AEF. To operate the telephone switchboard established at corps and army headquarters, Pershing recruited some two hundred women fluent in French. Trained by the American Telephone and Telegraph Company in Illinois, they were attached to the army’s Signal Corps. After purchasing their uniforms in New York, they were shipped to France and went to work. Known as the “Hello Girls,” they provided yeoman service and received praise from Pershing himself. What they did not receive was official discharge papers, medals, or veteran benefits. They were bluntly informed that, despite their uniforms and services, they were employees of the army, not members. They were not, therefore, entitled to benefits given to the men of the AEF. Not until 1979 was this injustice rectified, by which time, of course, it was too late for most of these women.

If America’s army required months and months to prepare for battle, it’s navy did not. On May 4, 1917, just twenty-eight days after the United States declared war, six American destroyers dropped anchor in Queenstown Harbor on the southern coast of Ireland. They and the others that followed would provide needed protection to the merchant ships sailing to and from Britain. Heavier naval firepower arrived in December. Five battleships of the United States Navy, all commanded by Rear Admiral Hugh Rodman, joined the Royal Navy’s Grand Fleet. Significantly, they served under British command and were present when Germany’s High Seas Fleet surrendered.

The U.S. Navy’s role in the First World War is overshadowed by that of Pershing’s army. For most Americans the image of the conflict is that of soldiers in trenches surrounded by mud and barbed wire. The navy’s contribution receives little notice. Even less is given to Admiral William S. Sims, who throughout the war was in charge of American naval operations in Europe.

In addition to dispatching destroyers and battleships to England, America’s navy established a special task force consisting primarily of cruisers that escorted the ships transporting the AEF to France. The navy also provided its air service to the war effort. This comprised some five hundred aircraft distributed among twenty-six naval air stations located in Britain, France, and Italy. And, rather remarkably, the navy sent five very heavy, large naval guns mounted on railroad cars to France, where, in the Allied offensives of September 1918, they pounded German positions near Soissons.

One other achievement of America’s navy in World War I deserves mention. As part of the effort to stymie German submarines, the Royal Navy proposed to lay a barrier of mines from northern Scotland across the North Sea to southern Norway. This would seal off the northern perimeter of the North Sea (a similar barrier was to be laid down across the English Channel near Dover). The project would deny the U-boats free access to the Atlantic Ocean. This was to be an enormous undertaking. Two factors initially delayed its start: the Royal Navy had few ships to spare, and, perhaps more important, British mines were defective. Enter the United States Navy. In June 1918, it began laying its own mines. In total, the Americans put 56,571 mines into the water. Britain’s navy laid 13,546. Together, they were strung along an underwater belt some two hundred miles long. Jellicoe’s successor, Admiral David Beatty, opposed the project. He said it would hinder operations of the fleet and consume resources better spent elsewhere. He had a point. The barrier, the Northern Barrage, to use its customary name, accounted for the destruction of only six U-boats.

Most German submarines operated in the waters around Great Britain and in the Mediterranean. Few made war patrols to North America. One that did was U-156. On July 19, 1918, off the coast of Long Island, the cruiser USS San Diego sunk, having struck a mine laid by the German submarine. The cruiser was the only major American warship lost in World War I.

***

In returning to unrestricted submarine warfare in 1917, Germany had gambled that it could force Great Britain out of the war before America’s involvement made much of a difference. The gamble failed. In 1914 Germany had gambled that it could destroy the French Army in forty days before having to move east against the tsar. This gamble also failed. Four years later, in 1918, Germany would take one last gamble.

Hindenburg and Ludendorff, by now running the government as well as the army, decided on one final offensive in the west. It would be a massive affair, employing specially trained storm troopers and army units no longer needed on the Russian Front. The attack began on March 21 with a thunderous barrage. Three separate German armies struck hard, crushing the British Fifth Army, one of four units under Sir Douglas Haig’s command. That first day, the kaiser’s men killed seven thousand British soldiers and took twenty-one thousand prisoners. The attack was a stunning success. The Germans advanced forty miles, a significant distance, before the British were able to stop them.

A second offensive took place in Flanders, the Germans attacking early in April. Here too they made progress, forcing the British commander in chief to issue his famous “backs to the walls” directive. Sir Douglas instructed his soldiers not to retreat, to hold on whatever the cost. His order was taken to heart. Here are parts of the written orders a young Australian officer issued to his men:

- This position will be held and the section will remain here until relieved.

- The enemy cannot be allowed to interfere with this program.

- If the section cannot remain here alive it will remain here dead, but in any case it will remain here.

- If any man through shell shock or other cause attempts to surrender he will remain here dead.

The men given this order obeyed. The order was found on the body of one of their dead.

In their spring offensives, the Germans also struck the French. Ludendorff, who planned the attacks, sent his troops to the Chemin des Dames sector, to the northeast of the Reims. There, they crushed a French army and advanced to the Marne River, threatening Paris. In June and July, the Germans, for the fourth and fifth time, again attacked. These attacks were less successful. Nonetheless, French forces had been battered. French troops were in retreat.

All along the front, German troops moved forward, inflicting a large number of casualties. In just the first forty days of combat, Sir Douglas Haig’s forces suffered more than 160,000 killed or wounded. French losses in the spring and summer reached 70,000. The British and French armies were bleeding, and bleeding badly.

As the casualties mounted, and the German advances continued, top Allied leaders realized that a change in the military-command structure was needed. Up to now the senior French and British field commanders, at the time Pétain and Haig, and earlier Nivelle and Haig, had acted independently. They consulted with each other, but neither could command the other. The German spring offensives changed that. All came to understand that a single field commander in chief needed to be in charge. Such was the urgency that Field Marshal Haig raised no objection to the appointment of French general Ferdinand Foch to the post (Pétain was considered too defensively oriented). The French general became, as Eisenhower would in the Second World War, supreme Allied commander. At first, he was simply to coordinate the three armies involved, the British, the French, and the American. But, as the German threat increased, Foch was authorized to give orders to their commanders. Only if Haig and Pershing considered these orders detrimental to the national interests of Great Britain or the United States were the two subordinate commanders allowed to appeal. Pétain had no such authority; he was told to follow Foch’s instructions. Despite disagreements, some rather testy, this new command arrangement proved satisfactory. Ferdinand Foch, the general who believed the only military course of action worthy of consideration was to attack, became commander of more than five million men. Given his preeminent position in the chain of command and his subsequent record of success, it’s not surprising that upon his death in 1920, his body was laid to rest in Paris near that of Napoleon.

As spring gave way to summer, the German offensives appeared to stall. Though inflicting heavy losses on their French and British counterparts, the Germans themselves suffered as well. By the end of April, after just two months, 492,720 of their soldiers no longer were able to fight. They were dead, in the hospital, missing in action, or had been taken prisoner. More German soldiers would be lost in May and June and into July, when, finally, after the fourth and fifth attack, the offensive came to a halt. In total, Ludendorff’s spring offensives cost the kaiser 800,000 of his soldiers.

Moreover, the British army, though roughed up, had not been destroyed. Sir Douglas’s men, by 1918 the most capable fighting force in Europe, had bent but not broken. So too the French. Pétain’s army, one that had experienced both victory and defeat in four years of conflict, still had some fight left in it.

As, of course, did the German army. Yet it was clear, especially to Foch, that the German spring offensives had failed. True, Ludendorff’s men had gained considerable territory. But no decisive victory had been attained, nor had the strategic picture changed much. The front, that tangled strip of trenches, barbed wire, and machine gun rests, had been moved to the west. Save for some worried souls in Paris, nothing much seemed to have changed.

In fact, two things had changed, both significant. The first was that the German army was running out of soldiers. A country can produce only a certain number of men capable of bearing arms, and by the summer of 1918, after fighting Russians and Romanians, the British and the French, Germany had just about reached its limit. And the later replacement troops were not as skillful as those who had fought earlier in the war. The second change, one even more ominous to Ludendorff and his field commanders, was that Pershing’s American Expeditionary Force was preparing to do battle.

***

The AEF’s first test of combat had come in late May. Assigned to the French First Army, the U.S. Army’s 1st Division was given the task of taking Cantigny. This was a small village on a ridge near Montdidier, a town some sixty miles north of Paris. The ridge enabled the Germans to observe what was taking place to the south and west of their positions. Planning the attack was the division’s Operations officer, Lieutenant Colonel George C. Marshall. Well conceived and twice rehearsed, the plan had the division’s 28th Infantry Regiment directly assaulting the town supported by artillery, tanks, and flamethrowers provided by the French.

The attack began early in the morning of May 28, 1918. By noon, the village was in U.S. hands. The Germans counterattacked several times, and the battle became what author David Bonk has called “a desperate slugging match.” Showing notable determination, the men of the 28th held on, despite the premature withdrawal of the French artillery. When the battle was over, the regiment had sustained more than nine hundred casualties. More importantly, Cantigny remained under U.S. control.

The town itself was of no overall strategic value to the Allies. But the fight for Cantigny was important. It demonstrated that the AEF could plan and execute a division-level operation. It also showed that, despite their inexperience, individual American soldiers would do just fine in battle. French and Britain commanders were uncertain how Pershing’s soldiers would respond to the ordeal of battle. So too were German commanders, who tried to convince their troops and themselves that Americans were no match for well-disciplined and battle-tested German soldiers. The fight for Cantigny put to rest such nonsense. For Foch and Haig it was reassuring. For Ludendorff it was cause for concern. For General Pershing and his troops, and for the folks back home in the United States, it was a signal that, once fully deployed, the AEF would have soldiers to be reckoned with.

As the 1st Division’s fight at Cantigny came to a close, the AEF’s 3rd Division was moving into action. Ludendorff’s May offensive, code named Blücher, had seen some success with the Germans reaching the Marne. The French, dispirited by their enemy’s advances, asked General Pershing for assistance. Recognizing the urgency of the situation, Black Jack put aside his objection to amalgamation and lent the 3rd Division to the French. They ordered it to Château Thierry. This was (and still is) a lovely little town on the Marne River, where today an American military cemetery resides. At Château Thierry the Americans held fast and Ludendorff’s troops advanced no farther.

Not far from Château Thierry, to the west, were two villages, Bouresches and Belleau. In between them stood a small forest. It was called Belleau Wood. In June 1918, it witnessed a fierce battle, one that for the United States of America would become legendary.

That same month, still needing to slow the German advance, Foch requested additional American help. However, he planned not just to halt the German drive. Foch planned to counterattack and wanted some of Pershing’s troops to participate. The AEF responded by lending Foch the 2nd Division, which the French deployed to Belleau Wood. This unit was unique in the American Expeditionary Force in that two of its four infantry regiments, comprising the 4th Brigade, were U.S. marines, not soldiers of the U.S. Army.

The 4th Brigade’s first task was to stop a German attack, which it did. The story is told that a retreating French officer said to an American that with the Germans advancing, he and his men should fall back. “Retreat, hell,” replied the marine, “we just got here.”

The second task assigned to the marines was to clear Belleau Wood of Germans and hold on to it. On June 6 they attacked. Their artillery was insufficient, their tactics flawed. But as the marines crossed a wheat field full of red poppies, their determination and courage were in full view. The attack succeeded, although the cost was high. The brigade’s casualties that day totaled 1,087. The fight would continue for twenty more days, and at times the marines took no prisoners, and neither did the Germans. It was kill or be killed.

Toward the end of the struggle for Belleau Wood, the 2nd Division’s other brigade, the one consisting of two army regiments, went into action. It was ordered to capture the nearby town of Vaux. Quite competently, the brigade took control of the town, for its effort suffering 300 dead and 1,400 wounded. This battle at Vaux received little attention. In 1918—and even today—what captured the spotlight was the marines at Belleau Wood.

By the standards of the First World War, the engagements of Belleau Wood and Vaux were small affairs. In total, the casualty count for the U.S. 2nd Division showed 1,811 men dead and 7,966 wounded. For the armies of France, Great Britain, and Germany, these were numbers unlikely to raise alarm. For the AEF 9,777 in one division was a stiff price. It illustrated that inexperience on the battlefield costs lives. Nonetheless, Vaux and Belleau Wood were victories. As did Cantigny, the two battles bode well for the Allied cause.

The next occasion in which the AEF went into action involved far more men than had fought at Vaux and Belleau Wood. Once the German spring offensive came to a halt, Ferdinand Foch was keen to strike back. He wanted to recover territory lost to the Germans, and he also wanted to damage Ludendorff’s army, which he believed by then to be under considerable stress. He directed Pétain to prepare a plan of attack, which the French army’s commander in chief did. The plan included substantial participation by the Americans.

Two U.S. divisions, along with a French Moroccan unit, spearheaded the attack. They were part of the French Tenth Army. Pershing had once again agreed to allocate American units to Pétain’s forces. Three other AEF divisions were assigned to the French Sixth Army, while a further three were part of the force held in reserve. Ultimately, some three hundred thousand American soldiers were involved. The attack, along a twenty-five-mile front in the vicinity of Soissons, began on July 18. It was over by August 2. Approximately thirty thousand Germans were taken prisoner. Such was the success that afterward the kaiser’s son wrote his father that the war was lost.

This battle is usually referred to as the Second Battle of the Marne. One key result of this battle was Ludendorff’s decision to call off a major attack against the British in the north. The German commander had hoped once and for all to crush Field Marshal Haig’s forces in France. That had been the decisive victory Ludendorff had designed his spring offensives to achieve.

Meanwhile, Sir Douglas had planned an offensive of his own, one to which Foch as Supreme Commander readily agreed. On August 8, the British Army attacked near Amiens. Among the assault troops were Canadians and Australians, whom the West Point Military Series account of World War I says were “generally regarded as the finest infantry fighters on the Allied side.” The outcome was a stunning success for British arms. Haig’s losses were light, suggesting that the British, at last, had mastered the art of trench warfare. German losses were substantial. Some seventy thousand troops were out of action. Of these, thirty thousand had surrendered without much of a fight. In his memoir, Ludendorff, who offered to resign after the battle, termed August 8 “the black day of the German army.”

The British victory at Amiens was one of the more decisive battles of the First World War, but not because of territory gained or men lost. Rather, it was important because of its psychological impact on the Germans. After Amiens the German high command realized that defeat was now likely. For Germany, the war was lost once its generals believed the war was lost. After their drubbing by the British in August 1918, that’s exactly what they began to believe.

Two days after the British launched their attack from Amiens, the American Expeditionary Force established a new combat organization. Previously, the AEF had organized divisions as its primary fighting units. As we’ve seen, these went into battle as components of various French armies. By August, however, the number of American divisions had increased so as to warrant a larger combat unit. On August 10, 1918, the First American Army was brought into being. It was comprised of fourteen divisions organized into three corps. Its commander was John J. Pershing, who remained in charge of the AEF, of which First Army became the principal American combat unit.

By early October, the number of American soldiers justified the establishment of the U.S. Second Army. Its commander was Major General Robert Lee Bullard, who had been in charge of the 1st Division at Cantigny. By then, First Army had a new commander. He was Hunter Liggett, also a major general. Both Liggett and Bullard reported to Pershing, who then was at the same level as Field Marshal Sir Douglas Haig and General Philippe Pétain, each of whose command encompassed several separate armies. Above Haig, Pétain, and Pershing was the supreme commander, Ferdinand Foch.

In early September Foch had been content to have Allied troops conduct limited offensives along the entire Western Front. For the AEF this meant the elimination of the St. Mihiel salient.

In military terminology, a salient is a wedge, a protrusion in the battle line often shaped like an arrowhead. In 1914, the Germans had created such a wedge sixteen miles deep into the French lines, with the tip of the salient at a small town well to the east of Paris. Several times, the French army had attempted to eliminate it. Each time the army had failed.

The St. Mihiel salient was in the American sector of operations. Not surprisingly, General Pershing decided to have his First American Army remove the wedge. Initially, he planned to have the army continue on to Metz, then a heavily fortified German stronghold. Such a move, if successful, would have had strategic consequences, threatening the position of all German forces on the Western Front. Foch, however, intervened. He wanted Pershing to abandon the attack on St. Mihiel and strike northwest into the Meuse-Argonne rather than northeast towards Metz. The Supreme Commander also wanted to insert a French army into the attack and place some of the American troops under French command. Pershing reacted strongly to both proposals, and the conversation between the two commanders became heated. The net result was a compromise. The American army would move against the salient but not proceed beyond it. And it would do so with fewer troops. But, acceding to Foch’s desires, the American First Army, with a large number of soldiers, then would advance into the Meuse-Argonne, striking northwest as the supreme commander wished.

The attack on the salient began on September 12 with an artillery barrage from 3,010 guns. Then, seven U.S. infantry divisions struck from the east. One American division attacked from the west, while French units advanced at the tip. In total, five hundred thousand American soldiers went into battle along with one hundred thousand French troops. Within two days, the salient was reduced. Pershing’s men took thirteen thousand prisoners and captured a large number of enemy guns. American casualties numbered approximately seven thousand.

Among the artillery pieces employed were the fourteen-inch naval guns. Mounted on railroad cars, they shot a projectile up to twenty-three miles and, if on target, were devastating to the enemy. The challenge, of course, was in correctly aiming the gun and properly gauging the ballistics of the projectile. At first the gunners had difficulty in hitting some of their targets. Help came from a young army captain. Edwin P. Hubble, who understood mathematics and the science of trajectories, provided the solutions. He later became an astronomer of note, winning a Nobel Prize. When in 1990 the American space agency, NASA, placed a powerful telescope in low earth orbit, the instrument was named for Dr. Hubble.

St. Mihiel was an American victory and celebrated as such. Once again, as at Cantigny, Château Thierry, and Belleau Wood, the AEF troops had fought hard. Indeed, the German high command took note of the Americans’ aggressive spirit. But the sense of victory from St. Mihiel must be tempered. It is generally conceded that a more experienced army would have taken a greater number of prisoners. In addition, the German army, aware of the forthcoming assault and of its vulnerability within the salient, had begun to withdraw. The fight was not as fierce as it might have been. Nonetheless, the American First Army had gone into battle and won.