9

VIETNAM

1965–1975

What makes the war in Vietnam unique in American history is its outcome. For no one can doubt that the United States lost the war. Defeat, not victory, was the end result. And the cost was extremely high—thousands of Americans slain and millions of dollars wasted. For the first time, the field of battle belonged to the enemy. The United States had been vanquished, and decisively so.

***

Much of the responsibility for the debacle of Vietnam rests with Lyndon B. Johnson (LBJ). As president, he directed the American war effort. And when he was in the White House, never far from his mind were the Chinese, whom Johnson was determined to avoid engaging in battle. He remembered that in 1950, when U.S. troops in Korea approached the Yalu River, China had sent wave after wave of its soldiers into battle, crushing an American army. Fifteen years later, in 1965, Johnson did not want to see Chinese troops in Vietnam, a country in which America was fighting a Communist regime based in Hanoi. Nor did he want a war with China itself. The president thus conducted the war in Vietnam with restraint. From 1965 until 1968 the United States did not unleash its military. Indeed, America limited its approach to battle, applying its firepower gradually. This, it was hoped, would keep Chinese troops at home. It also was intended to restrain the Soviet Union. And too it demonstrated to friends of the United States, particularly the Europeans, that America was reasonable when committing its military to combat.

In Vietnam, Lyndon Johnson most certainly did not want to ignite a world war, a conflict that might well occur were China and the United States to do battle with each other. And significantly the President did not wish to jeopardize his Great Society program. This was an ambitious agenda of legislative initiatives, including a major expansion of health care, that surely would fail were the U.S. at war with China.

Hence LBJ conducted the war cautiously, holding back the admirals and generals who wished to overwhelm the North Vietnamese. These commanders wanted to employ the full might of America’s superb army, navy, and air force. They believed that if young Americans were to die in Vietnam, the least their leaders could do was to achieve victory. But Johnson held these commanders at bay. The United States would fight in Vietnam, but not so as to obliterate the enemy in the north.

Why then did the United States fight at all? If the objective was not to destroy the North Vietnamese regime, if at all costs the Chinese (and Russians) were to be kept out of the battle, and if American military leaders were to be held in check, why send troops to Vietnam? After all, according to many experts, America’s national security was not at stake in Vietnam. Whatever happened there was unlikely to harm the United States.

The answer is twofold. One reason is that, at the time, the principal focus of U.S. foreign policy was the containment of Communism. As leader of the Free World, the United States was committed to holding back the spread of a ruthless political ideology. Whether Republican or Democrat, America’s leaders believed their job was to halt the spread of Communism. So Lyndon Johnson, as well as his predecessor in the White House, John F. Kennedy, dispatched American servicemen to South Vietnam. The two presidents saw in this small country the necessity of standing firm against the beliefs espoused by Karl Marx and Vladimir Lenin.

A second reason for U.S. troops being sent to Vietnam stemmed from American domestic politics. As a Democrat, LBJ remembered how years earlier the Republicans in Washington had savaged the Democrats for “losing” China. That China fell to the Communists in 1949 was interpreted as a catastrophic failure on the part of Harry S. Truman and his fellow Democrats. In fact, China’s American-backed regime gave way to Mao Tse-tung because China’s then leader, Chiang Kai-shek, was incompetent. Facts, however, played little part in the partisan warfare then prevalent in the American capital. The Republicans blamed the Democrats for Chiang’s defeat. In so doing, they scored political points and were able to defeat the Democrats in the 1952 elections. Lyndon Johnson vowed he never would be tarred with such a brush. So he went to war in 1965. Johnson was determined not to be the president who lost South Vietnam.

***

America’s involvement in Vietnam did not begin with Lyndon Johnson or John Kennedy. It began much earlier, soon after the end of the Second World War. In 1946 the French returned to Indochina, the geographic term employed to describe what is now the countries of Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam. These had been French colonies, and officials in Paris were eager to reclaim them.

However, many Vietnamese took exception to French rule, particularly Ho Chi Minh, leader of the Vietnamese Communists. Ho and his comrades decided to contest French control of Vietnam. There ensued an eight-year war in which Paris attempted to put down the insurrection. In this the French were aided by the Americans, who, anxious to halt the advance of Communism, financed the effort and supplied large amounts of military equipment. The conflict came to an end in May 1954, when the Vietnamese overwhelmed the French fortress of Dien Bien Phu.

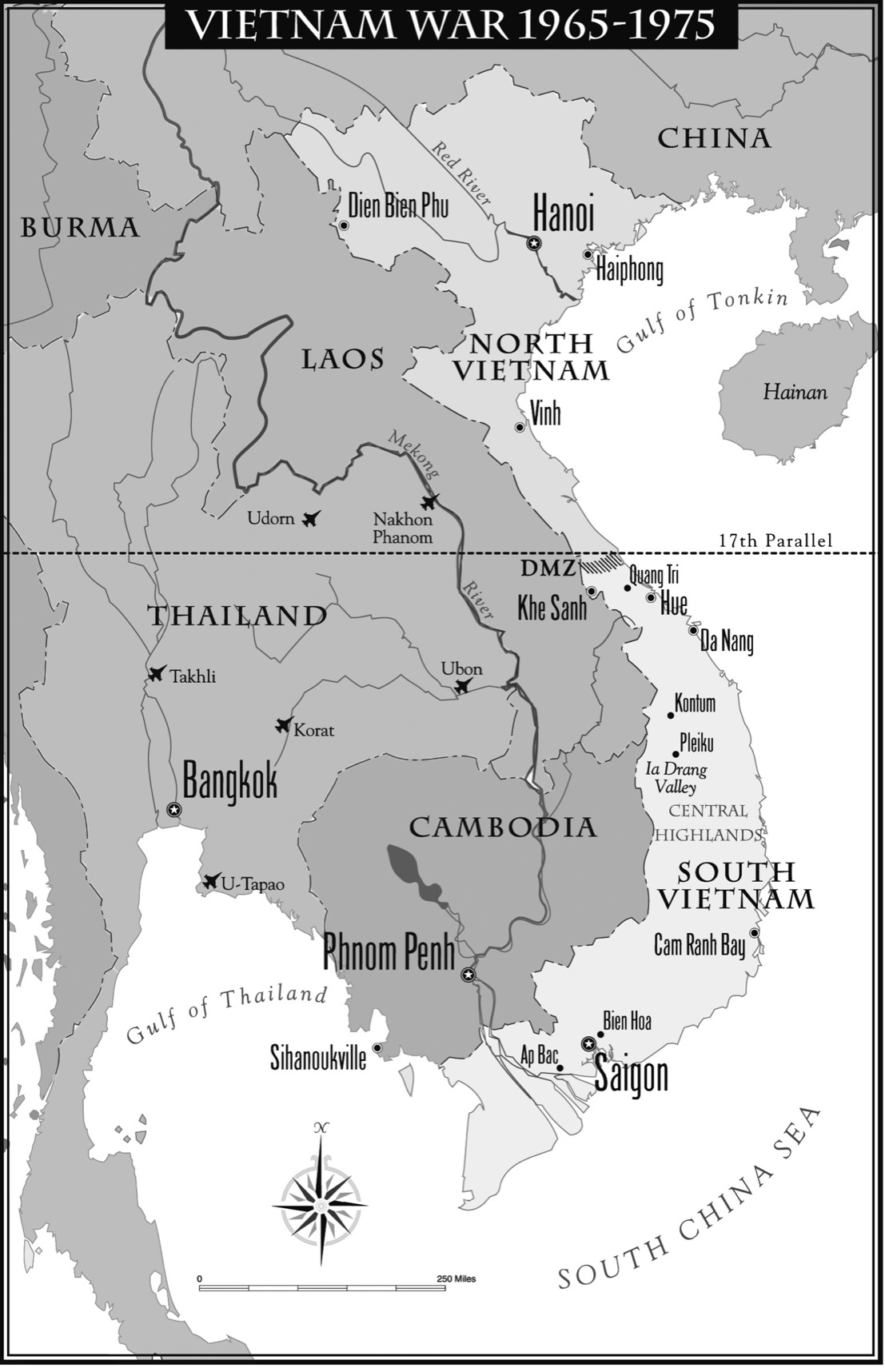

The French army’s defeat led to negotiations in Geneva at which the French government agreed to withdraw from Indochina. Laos and Cambodia were declared independent, neutral nations. Vietnam was divided into two parts, separated at the 17th Parallel by a demilitarized zone (DMZ). Each part had its own government. To the north, based in Hanoi, was the government of Ho Chi Minh. South of the DMZ, in what came to be called the Republic of South Vietnam, was a pro-Western government. This soon was run by an ardent anti-Communist, Ngo Dinh Diem. In two years, so the Geneva Accords stated, an election would be held across all of Vietnam. The winner would rule a single, united nation.

The election never took place. Diem knew the outcome would favor Ho Chi Minh, if only because the population of the north outnumbered that of the south. Ho himself violated several provisions of the agreement, and before long, the two sides were at war. Throughout the conflict, Vietnamese from the north would infiltrate villages and towns in the south. Ho and his comrades hailed these men as liberators. Others did not, especially because their tools of persuasion included terror, extortion, and murder.

In support of Diem, President Dwight D. Eisenhower provided military assistance to counter the growing Communist threat. This assistance included U.S. Army advisors. Their role was to train the South Vietnamese army (known to the Americans by its acronym ARVN, which was pronounced “R-VIN,” and stood for Army of the Republic of Vietnam). President Kennedy significantly increased the number of advisors, so that by the end of 1963 some sixteen thousand American soldiers were teaching Diem’s troops how to fight. General Earle Wheeler, who in 1963 was the army’s chief of staff, called the advisors “the steel reinforcing rods in concrete.”

The steel was strong, the concrete less so. In battle, ARVN troops often did poorly. Primarily, they suffered from the absence of capable senior commanders. Diem wanted generals who, above all, were loyal to him. He viewed talented generals as a political threat. Moreover, the good commanders were willing to fight, and this caused casualties, which added to Diem’s problems. Shortcomings of the South Vietnamese army were revealed in January 1963 when, near the village of Ap Bac, ARVN troops were routed by the enemy.

Yet the problems for Diem and his American allies were deeper than the South Vietnamese army. The problem was South Vietnam itself. The country lacked political cohesion. It enjoyed no tradition of democracy or of central government. Its population was fragmented: different groups—the Buddhists, the merchants, the army, and the Catholics (who, though a minority, exercised great influence)—were loyal primarily to themselves. They felt little obligation to the state and seemed to thrive on corruption and self-interest. How Diem or anyone else could rule such a land was a question not easily answered.

The battle of Ap Bac revealed another problem that would make difficult the U.S. Army’s campaign in Vietnam. Despite the negative outcome of the fight at Ap Bac, U.S. commanders in Saigon, the capital of South Vietnam (renamed Ho Chi Minh City early in 1975), insisted the battle had been a victory for the ARVN. American media representatives knew better. They challenged the commanders who, echoing the party line that the South Vietnamese troops were improving and had carried the day, refused to acknowledge the truth. And so began the skepticism on the part of U.S. journalists covering the war toward pronouncements emanating from the American army. As the war progressed, the skepticism would grow. At times, the media considered army bulletins less than truthful. In turn, army officials felt reporters emphasized the bad news and ignored the good. More than a few army officers in Vietnam believed the media wished the enemy to win.

Throughout the conflict, the enemy consisted of the Vietnamese native to the south who were opposed to the government in Saigon, as well as northerners who had been ordered to move south and challenge the Americans and their Vietnamese allies. Hanoi would claim that the native southerners were an independent entity, without ties to the north. Not so. Communist leaders in North Vietnam were always in charge. To the Americans the southern insurgents were the Viet Cong, or sometimes simply “Charlie.” The northerners were regular troops of the North Vietnamese Army known informally as “the NVA.” Because President Johnson, in an effort to appear less warlike, had told the government in Hanoi that the U.S. did not seek its destruction, most of the north’s army was deployed either in the south or next door in Laos and Cambodia. These troops numbered in the thousands and, as American G.I.s would discover, were tough, well-disciplined soldiers.

As 1963 drew to a close, the situation in Vietnam, from the perspective of the United States, was deteriorating. Despite the presence of American advisors, the performance of the ARVN left much to be desired. As important, if not more so, was the fact that Diem’s rule was unraveling. There was increasingly strong opposition to the man and his government. No better example of the turmoil exists than the actions of the Buddhist monks in Saigon. Several of them—to a worldwide audience—committed deliberate acts of self-immolation: they would drench their bodies with gasoline then set themselves ablaze. So, with American acquiescence, the South Vietnamese army moved against Diem. On November 1, the generals struck. Diem was seized and killed.

There followed a succession of military-led governments, a few of which made efforts to improve not only the army but also the lives of the average Vietnamese, many of whom cared not a whit who governed in Saigon. At times these latter efforts, financed largely by the United States, produced the intended results. But, in the long run, marred by incompetence and by the corruption endemic to Vietnamese society, the programs failed.

President Kennedy had made a second key decision with regard to Vietnam, in addition to that of vastly increasing the American presence. He authorized a covert program of harassment and surveillance along the southern coastline of North Vietnam. South Vietnamese rangers raided the north while U.S. Navy ships conducted electronic espionage offshore. When Lyndon Johnson continued these operations, the stage was set for one of the more important chapters in the story of America’s war in Vietnam.

***

Early in August 1964, the American destroyer Maddox was several miles off the coast of North Vietnam, carrying out electronic surveillance. Responding to this intrusion, North Vietnamese torpedo boats attacked the ship. The Maddox returned the fire, hitting at least one of the boats. An hour later, U.S. warplanes from a nearby carrier also struck the North Vietnamese craft. President Johnson chose not to reply further, but he did authorize the continuation of the spying missions.

Two days later, on the night of August 4, another destroyer reported (apparently erroneously) that it had come under attack. This time, LBJ hit back hard. He ordered the U.S. Navy to strike the torpedo boat bases. These were located at Vinh, on the coast of North Vietnam some two hundred miles north of the DMZ. Sixty-four planes from two aircraft carriers, the Ticonderoga and the Constellation, did so, severely damaging the base. Two aircraft were lost; one of the pilots was killed. The other, Lieutenant (j.g.) Everett Alvarez, became a prisoner of war (POW). He would be the first of many, eventually serving eight years in captivity before being released in March 1973 along with 586 other American POWs.

President Johnson’s decision to attack the North Vietnamese naval facilities at Vinh served his political agenda. In the midst of the 1964 presidential election, LBJ could use the attack as proof that he was capable of being firm when necessary. This was particularly useful to his reputation as his Republican opponent, Senator Barry Goldwater of Arizona, a hard-liner, was projecting Johnson as a timid liberal, unwilling to employ America’s military might.

Not satisfied with the attacks on Vinh, Lyndon Johnson sought specific authority to take whatever steps he deemed necessary to repel further aggression against the United States. If he, as president of the United States, were to place America’s armed forces in harm’s way, he wanted the U.S. Congress alongside, sharing the responsibility. So Johnson went to the legislature and got what he sought. Known as the Tonkin Gulf Resolution, it gave the president a blank check for military action. The House of Representatives passed the resolution 116–0. In the Senate the vote was 80–2. That Lyndon Johnson withheld information regarding the South Vietnamese raids and the American surveillance missions made gaining approval of the resolution easier than it might have been.

Three months after the North Vietnamese fired on the Maddox, Americans again were attacked, this time on land and in South Vietnam. On November 1, 1964, the Viet Cong struck a small American air base at Bien Hoa, just north of Saigon. Four Americans were killed, twenty-six wounded. Four airplanes were destroyed. Then, in December, the VC blew up an officer’s billet in the South Vietnamese capital, causing additional casualties. In February 1965, the VC struck again, with deadly results. They hit a U.S. Army helicopter base at Pleiku in the Central Highlands. Eight soldiers died. Seventy-six were wounded and several helicopters were disabled. Three days later the Viet Cong blew up a building in Qui Nhon, killing twenty-three Americans. Clearly, the VC were challenging America’s presence in Vietnam.

Lyndon Johnson felt he had to respond. And he did. The president ordered U.S. marines to Da Nang in order to secure the airfield there. They arrived, in battle gear, on March 8, 1965. Soon thereafter, they were directed to undertake offensive operations against the Viet Cong. For all practical purposes, the United States had gone to war.

To this war the president fully committed the United States Air Force. Responding to the attacks by the VC, particularly at Pleiku, Johnson ordered American warplanes to strike targets in North Vietnam. Thus began the aerial campaign known as Rolling Thunder. A signature feature of the war in Vietnam, the effort continued, interrupted by several pauses, until the end of October 1968. In the long history of American arms, few operations, whether by land, in the air, or at sea, aroused such controversy as Rolling Thunder.

***

A typical mission of the Rolling Thunder campaign would involve sixteen or more attack aircraft. These would fly from bases in Thailand and, once airborne, would rendezvous with fighter escorts. Heading north, the aerial armada would refuel from air force tankers (military jets were and are gas guzzlers), receive guidance from nearby electronic warfare planes, and proceed into enemy airspace.

For much of Rolling Thunder the principal strike aircraft was the Republic F-105 Thunderchief. This was a large, single-seat fighter-bomber. The plane was fast (1,372 mph at 36,000 feet) and would carry 14,000 pounds of bombs plus several Sidewinder air-to-air missiles, the latter of which would be useful were enemy aircraft to be engaged (as was the 29 mm cannon carried within the plane’s fuselage). Based at Korat and Takhli, the Thunderchiefs flew thousands of sorties. But the cost was high. During the war the U.S. Air Force lost 397 F-105s, nearly half the number built.

Also participating in Rolling Thunder, indeed perhaps the airplane most widely employed by the United States in Vietnam, was the McDonnell Douglas F-4 Phantom. This too was big and fast. But, unlike the F-105, it had a crew of two, a pilot and a weapons-radar officer. In Vietnam, the Phantom was used as both a fighter and as a bomber, as well as a reconnaissance aircraft. Early versions of the F-4 carried no guns. They were armed only with missiles. This turned out to be a mistake and soon was rectified. With its powerful radar and impressive rate of climb, plus the capability to carry tons of bombs, the Phantom was a formidable machine. That its General Electric jet engines emitted lengthy trails of black smoke, making the plane easily visible, was cause for concern. Yet the F-4 did well in combat, especially when crewed by men who knew their trade.

Although the Phantom equipped numerous air force squadrons, the plane was designed and manufactured for the United States Navy, which deployed the F-4 aboard its aircraft carriers (no doubt air force generals winced when ordering a plane its sister service had developed). America’s naval air arm played an important part in Rolling Thunder. The navy placed three and sometimes four carriers off the coast of North Vietnam (“Yankee Station”) as well as ships farther south (“Dixie Station”). These latter vessels provided air support to friendly troops on the ground in South Vietnam. The aircraft carriers to the north would spend three or four days conducting air strikes, then withdraw to replenish at sea, having depleted onboard supplies of food, ammunition, and the hundred or so odd things necessary to keep a large ship operating.

Both the navy and the air force pilots flying over North Vietnam during Rolling Thunder operated under strict rules of engagement. These specified what could and could not be attacked. Targets in and around Hanoi and Haiphong were off-limits. At first so were enemy airfields. When antiaircraft missile sites were being constructed north of the DMZ, the Thunderchiefs and Phantoms were not allowed to hit them, for fear of killing Russian technicians who were advising the North Vietnamese on how to operate the weapon. Further, the American planes were not to fly inside a twenty-five-mile buffer zone extending from Vietnam’s border with China.

Needless to say such restrictions made Rolling Thunder less effective than it might have been. Pilots, in particular, objected to the rules. One F-105 pilot called them “extensive, unbelievable and decidedly illogical.” Author Stephen Coonts said they ensured that the United States would not win the war.

Why were the Rules of Engagement put in place? The answer is that Lyndon Baines Johnson, not trusting America’s senior military leaders, wanted to make sure that the conflict would not escalate, which it might if the North Vietnamese were to be hit extremely hard. He also wanted to minimize civilian casualties which, were they to occur in large numbers, would pose political problems for the president both at home and abroad.

U.S. generals and admirals chafed at the restrictions. Intent on winning the war, they wanted to bomb Hanoi (a city that, because of the rules air force historian Wayne Thompson described as “one of the safest places in Vietnam”), mine the harbor of Haiphong, cut North Vietnam in half by an amphibious invasion, and generally conduct the war in a manner guaranteed to bring the north, if not to its knees, at least to the bargaining table. If young Americans were to die in Vietnam, these commanders reasoned, did their country not owe them the goal of victory?

But President Johnson was so determined to keep control that he and his secretary of defense, Robert McNamara, instituted a targeting procedure unlike any that had ever been seen. Targets for warplanes striking North Vietnam had to be approved by the White House. Air force and navy leaders would submit proposed targets to the defense secretary, who would massage the list and forward his recommendations to the president. Johnson and a few civilian advisors then would choose what could be struck and what could not. Sometimes, they even decided what size of bomb could be used and what routes the aircraft would take going in and out of Vietnam.

Many targets made military sense. Bridges, rail junctions, and truck convoys were all permitted to be hit. But often, too often to the men who had to do the bombing, the targets seemed hardly worth the effort, or the risk. One F-105 pilot, Ed Rasimus, in a fine book recounting his experiences flying in Vietnam, wrote the following:

The target itself was described as “approximately fifty barrels of suspected [petroleum].” The pilots had all agreed in the planning room that we must have indeed been winning the war if we were sending sixteen bombers, five SAM-suppression aircraft, eight MiG-CAP, two stand-off jammers, and eight tankers for fifty barrels of something buried at a jungle intersection. The briefing officer seemed a bit embarrassed by the target. . . . It wasn’t his fault, so we didn’t harass him. Credit for targeting rightly belonged in Washington.

To say this targeting procedure was unusual would be an understatement. To say it made no sense would be more to the point. Surely, the president of the United States had more important tasks than selecting targets for Rolling Thunder. Lyndon Johnson didn’t think so. He wanted to be sure control did not pass to the military. His purpose was to limit the war in Vietnam, and he thought target selection was one way to do so.

Johnson’s strategy for Rolling Thunder was to increase gradually the aerial violence. He believed that such an approach would induce the North Vietnamese, who, realizing that even further destruction would be forthcoming, to come to their senses and agree to a negotiated settlement. Johnson believed he was acting rationally and responsibly. He was avoiding overkill and, by ordering a number of bombing pauses, was giving the regime in Hanoi an opportunity to act in a similar manner. The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) advised the president that this approach would not work. The agency pointed out that the North Vietnamese Communists were interested only in victory, which for them meant the removal of the regime in Saigon, the withdrawal of U.S. troops from Vietnam, and the unification of the two Vietnams under one rule, theirs. Lyndon Johnson, a master of political compromise, thought differently. He believed the North Vietnamese would act as he might act. They would see what he saw and realize their interests would be served by agreeing to a settlement, thus avoiding further destruction from American warplanes. But Lyndon Johnson was wrong, his strategy flawed. The North Vietnamese had no intention of agreeing to any settlement that deprived them of victory.

Ed Rasimus survived his tour flying F-105s, completing one hundred missions over North Vietnam. Other pilots were less fortunate. They were shot down, and either killed or taken captive. In 1966 and 1967 alone 776 U.S. airmen lost their lives. In total, the United States saw 992 aircraft destroyed during Rolling Thunder. There were wrecks of Thunderchiefs and Phantoms all over North Vietnam.

One of those F-4s went down on July 24, 1965, early in Rolling Thunder. What makes the event noteworthy was the cause of the plane’s destruction. The Phantom was hit by a Russian-built SA-2 surface-to-air missile (SAM).

Deployed in great numbers throughout North Vietnam, the SA-2 was a modern air defense missile supplied in large numbers by the Soviet Union. With a warhead containing 420 pounds of explosives, the missile could bring down an aircraft at altitudes up to eighty thousand feet. However, the missile was susceptible to electronic jamming, a tool at which the Americans became extremely proficient. Both the U.S. Air Force and Navy produced specialized aircraft and tactics to jam the missile’s guidance system. The air force called these planes “Wild Weasles.” They were all two-seater warplanes that locked onto SA-2 transmissions and then fired a missile of their own at the launch site. While not always successful, the Wild Weasles put a major dent in the north’s missile defense system.

During the war, according to SA-2 historian Steven Zaloga, a total of 5,804 missiles were fired at American aircraft. In the eight years of conflict, SAMs destroyed 205 U.S. planes. However, the impact of the missile was greater than this tally might indicate. That’s because the SA-2s caused many of the attacking aircraft to jettison their bombs before reaching their target. Moreover, they forced American planes to dive to lower altitudes, bringing them within range of antiaircraft guns the North Vietnamese had placed all across their country.

The antiaircraft guns and the SA-2s were parts of a triad that together constituted a formidable air defense system. The third element of North Vietnam’s air defenses was the MiGs. These were Russian-built jet fighters, and they constituted the core of the small but determined Vietnamese People’s Air Force.

While the two air forces met in combat over North Vietnam, aerial battles were not frequent. Nevertheless, the Americans did shoot down 196 MiGs during the war. However, the primary objective of U.S. airpower was not the downing of MiGs. The principal goal was putting bombs on target.

Despite the extensive bombing campaign against North Vietnam, Rolling Thunder was not a success. Why? Because the campaign, though military in character, was essentially an exercise in international politics. The purpose of Rolling Thunder was to convince the regime in Hanoi that the price it would have to pay to overthrow the government in Saigon was too high and that it should stop the infiltration of men and matériel into South Vietnam (these flowed south through Laos and Cambodia, along a series of trails nicknamed the Ho Chi Minh Trail). Notwithstanding the pounding by American aircraft, neither of these objectives was achieved.

However, Rolling Thunder did accomplish one secondary goal Lyndon Johnson and Robert McNamara had set for the campaign. The goal was to boost morale in the south and buy time for the government there to improve its effectiveness. Rolling Thunder sent a message to leaders in Saigon that, in the fight against the Communists, they were not alone.

***

More visible evidence of the American commitment was the increasing number of U.S. troops on the ground in Vietnam. After the initial landings at Da Nang in March of 1965, the number of soldiers steadily increased. By the end of that year, the army had 184,000 men “in country.” Twelve months later the number stood at 385,000. By April of 1969 there were 543,400 American soldiers stationed in Vietnam. This represented the peak of the army’s troop deployment. Afterward, that number declined. By December 1971, only 156,800 soldiers were in Vietnam. By the end of 1972, the number had been reduced to 24,200.

Other nations, allies of the United States, contributed troops as well. Australia, New Zealand, the Philippines, and South Korea all sent soldiers to Vietnam. And their numbers were not inconsequential. Australia dispatched some 7,600 troops, South Korea approximately 50,000. In its battle against the VC and NVA, the United States did not stand alone.

The buildup of troops that began in 1965 was intended to save the regime in Saigon from collapse, which it did. It also had the effect of turning the war into an American effort. Not everyone thought that was a good idea. CIA director John McCone told Lyndon Johnson that such increases meant the United States would get bogged down in a war it could not win. But Johnson, concerned by the political ramifications of defeat, approved the increases.

However, the president did not announce the troop deployments with any fanfare. Indeed, he downplayed them. Worried about the fate of his legislative initiatives, Johnson made every effort to conceal from the American public the expanding scope of the war. This, combined with the optimistic assessments of the conflict regularly issued by the army, would bring trouble in the future for both the president and his generals.

One of those generals was William C. Westmoreland. At one time the services’ youngest major general, Westmoreland had attended Harvard Business School and, from 1960 to 1963, was superintendent of the United States Military Academy. More relevant to our narrative, from 1964 to 1968, Westmoreland was the senior American officer in Vietnam. He was the general in charge of the war.

Westmoreland’s strategy was to aggressively go after the Viet Cong and the NVA. Despite requesting and receiving more and more troops, Westmoreland did not have the number that would enable him to occupy most of the battlefield (which comprised essentially all of South Vietnam). So he did the next best thing. He pursued the enemy, seeking them out, hoping to crush them via superior American firepower. This strategy came to be known as “search and destroy.” Essentially, Westmoreland’s plan was to wear down the enemy, to kill so many of the Viet Cong and North Vietnamese regulars that they would either give up or fade away. It was a strategy of attrition. For Westmoreland and his soldiers it was a sensible way to fight. Unfortunately for the general and his troops, it would not have the results he desired. This despite the fact that in combat with the enemy, the U.S. Army in Vietnam never lost a battle.

One of the first battles in which the U.S. Army encountered the NVA gave Westmoreland hope his strategy would prevail. In October 1965, in the Ia Drang Valley, the north had assembled a large number of troops with the intent of splitting South Vietnam in half. U.S. intelligence officers got wind of the plan, whereupon Westmoreland sent the 1st Air Cavalry Division into action. Transported by helicopter, the troops engaged the enemy and, after fierce fighting, emerged victorious. In the battle, the first in which a large unit of the American army participated, at least 600 North Vietnamese were killed. Many, many more were wounded. American dead numbered 305. The outcome helped convince the Americans they would win the war.

One reason for the U.S. Army’s success in the Ia Drang Valley was the extensive use of helicopters. Roads in Vietnam were limited in number and size, thus making difficult the rapid movement of men and supplies. Employing helicopters therefore made great sense. These machines gave the Americans an advantage in mobility, which, when combined with the army’s firepower, provided Uncle Sam’s troops a formula for success.

Helicopters were used in Vietnam to locate the enemy, to carry troops into battle, to resupply them when necessary, to airlift the wounded back to hospital, and to withdraw troops once the battle had concluded. At times equipped with extra machine guns and rockets, helicopters also were employed as attack aircraft spewing forth death and destruction. Helicopters flew every day of the war. Such were their employment that, for Americans both in Vietnam and at home, they became the iconic image of the war. One type of helicopter was ever present. This was the Bell UH-1. Formally christened the Iroquois (as the U.S. Army named its helicopters after Native American tribes), the machine was universally known as “the Huey.” Illustrative of the scale of the conflict in Vietnam, approximately 2,500 Hueys were destroyed during the war. Many of their pilots were among the 2,139 helicopter airmen killed in action. Another 1,395 men were lost from non-battle-related helicopter crashes.

During 1966 and 1967 the tempo of the ground war picked up as General Westmoreland moved aggressively to engage the Viet Cong and the NVA. That first year his troops conducted eighteen major operations. In 1967 two of his efforts received much attention. They were called Operation Cedar Falls and Operation Junction City. The first took place in January. Westmoreland sent thirty thousand U.S. and ARVN troops into what was known as the Iron Triangle. Comprising some 125 square miles, this was an area twenty miles northwest of Saigon, heavily infested with the enemy. A month later, the general launched Junction City. This too involved a large number of troops. It occurred in War Zone C, an area of 180 square miles close to the Cambodian border. In each operation, Westmoreland’s soldiers did well, inflicting heavy casualties on the enemy. U.S. casualties were light. In Operation Cedar Falls they numbered 428, in Junction City a little less.

In both endeavors Westmoreland’s men won the day. The problem was that, while the general and his troops defeated the enemy, they did not destroy them. During both battles, and in a pattern that was repeated throughout the war, the VC and NVA would fight, disengage, and then escape into Laos or Cambodia (both countries theoretically were neutral, but in fact served as sanctuaries for those Vietnamese fighting the Americans). In other words the Viet Cong and the North Vietnamese regulars would live to fight another day.

Because the war in Vietnam did not involve traditional lines of separation between the two sides—no front lines existed, ahead of which lay the enemy—measuring success was not easy. Westmoreland could not point to a map and say his army had seized from the VC or NVA this amount of territory or that amount of land. How then to measure progress? The general had an answer. As his strategy was one of attrition, success would be measured by the number of enemy killed. Kill large numbers of VC and NVA, and success or failure could be determined. Or so the general argued.

Thus came into being one of the hallmarks of the Vietnam War. This was the body count. After each engagement, commanders reported the number of the enemy who lay dead on the field of battle. This number was reported up the chain of command, eventually reaching the secretary of defense, a man who relished statistics. Because an army officer’s performance evaluation was influenced heavily by the number of enemy his unit had killed, the numbers often got inflated. This resulted in a focus on body counts as well as a distortion of the progress being made. That army officers in the field could not always distinguish between civilian dead and enemy killed made the metric even more unreliable.

This emphasis on statistics (some would call it an obsession) extended to the air force as well. Secretary McNamara wanted numbers, so what mattered to the generals in blue were sorties flown and bombs dropped. That the latter more than occasionally missed their target mattered little, and certainly less and less the closer to the secretary the general was. As noted above, Robert McNamara wanted statistics, and because he denigrated those who believed war was as much about morale and tactics, it was statistics he got. Then and now, many would agree that the man went to his grave not understanding the nature of warfare. He thought it was an exercise in accounting.

By the end of 1967, a year in which much fighting had taken place, both sides of the conflict had reason to worry. For the United States, casualties were mounting. Rolling Thunder was not working, and the ARVN still was not the fighting machine U.S. advisors had hoped to create. At home opposition to the war was growing.

In part, this opposition was stoked by the images of violence seen by Americans on their television sets. Vietnam was the first televised war. On nightly newscasts the people of the United States saw for the first time the ugly aspects of war. Often the images were shocking. The result was a conviction on the part of some that war in general was wrong and that this war, in particular, was immoral.

Among those protesting the war were religious leaders who spoke out against U.S. participation in what they deemed a civil war among the Vietnamese. Liberals too opposed the war, often not peacefully. Students, many of them eligible for the draft, took to the streets instead of the classroom. Making matters worse were the racial tensions endemic to an America that overtly discriminated against its citizens whose skin was black (and who, in large numbers, served in the army that was fighting in Vietnam). In 1967 and early in 1968, especially in April of the latter year, when Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated, racial tensions exploded. People were angry, and civil discourse often gave way to violence. Yet, despite the dissent, Lyndon Johnson persevered. So did General Westmoreland, who continued to issue optimistic assessments of the progress being made.

In Hanoi no protests were taking place, but Communist leaders had cause for concern. Their casualties too were mounting, American troops were flooding the south, American aircraft were wreaking havoc all across their country, and the government in Saigon—whom they despised—seemed nowhere near collapse, and neither was the ARVN in full retreat. From their perspective the war was in stalemate.

In July 1967, the Communist leaders decided to break the stalemate. They fashioned a plan they expected would topple the South Vietnamese government, shatter the ARVN, cause an uprising throughout the south, and force the United States to withdraw. The plan—they referred to it as the General Offensive—would begin with attacks in the countryside to draw Westmoreland’s troops away from densely populated areas. Then, having covertly moved men and supplies into position, they would launch strikes on the cities and towns across South Vietnam. To achieve maximum surprise, the attacks would occur during a traditional Vietnamese holiday when most people would be limiting their daily activities. The holiday, celebrating the beginning of the new lunar year, was called Tet.

The North Vietnamese initiated their General Offensive, which would become known to Americans as the Tet Offensive, as planned. Late in 1967, they and their Viet Cong compatriots began attacking American and ARVN outposts that were far from the populated centers of South Vietnam. One of these, Khe Sanh, became a major battle, longer and bloodier than either side had anticipated.

Khe Sanh was a marine outpost near the Laotian border, just south of the DMZ. When General Westmoreland received intelligence reports that the enemy was amassing troops there—eventually the NVA would deploy twenty thousand soldiers in the hills surrounding the base—he believed they were attempting to repeat their triumph at Dien Bien Phu. Westmoreland welcomed the news, as he was eager to engage the VC and NVA in a pitched battle. The resulting struggle—it began when the Vietnamese attacked the marines on January 23, 1968—lasted seventy-seven days. American casualties in the battle numbered 1,029, of whom 199 were killed. Reflecting the efficacy of American firepower, at least 1,600 of the enemy were dead, with thousands wounded.

In the United States the siege of Khe Sanh received extensive media coverage. Aware that loss of the base would be a political disaster, Lyndon Johnson required his military advisors to state in writing that the base would be held. Were it to fall, the president intended to deflect the inevitable flood of criticism to the military.

One reason the marines at Khe Sanh held the enemy at bay was the massive use of tactical air support. U.S. Air Force and Navy planes pounded the enemy with bombs and rockets, flying some twenty-four thousand air strikes. Joining the battle were the giant B-52s. These huge aircraft conducted numerous missions in support of the marines. Rarely has airpower been so successful.

The Americans believed Khe Sanh was a victory. The marine base was not overrun, while a large number of the enemy were put out of action. Yet the North Vietnamese also considered the siege a success. They argued that General Westmoreland was forced to pour reserves into the fight, thereby weakening the forces available to counter the main thrust of the General Offensive. Their official history of the war states that Khe Sanh represented “a serious military and political failure for the American imperialists. This failure demonstrated the impotence of their strategically defensive posture.”

At the task of assembling men and weapons for the General Offensive the North Vietnamese proved masterful (no doubt helped by the fact that their agents had penetrated practically every organization comprising the government of South Vietnam). At having all their teams strike at exactly the same time they were less successful. A few of the teams attacked prematurely, thereby alerting the Americans, who, via intelligence sources, knew that the Communists were planning some sort of attack. When, as a result, General Frederick Weyand, one of Westmoreland’s senior commanders, redeployed his troops, the Americans were in a much better position to repel the attacks.

The main strikes took place on January 21, 1968. They were hard-hitting and extensive. Vietnamese teams struck in thirty-six of forty-four provincial capitals, in sixty-four district capitals, and hit many, many military installations. In Saigon, they blasted their way onto the grounds of the U.S. Embassy. The scope of the attacks stunned the Americans. But Westmoreland’s men rallied, as did the ARVN. Together, they threw back the attackers. In some places the fighting lasted several weeks. But, when it was over, North Vietnamese casualties were heavy—approximately forty thousand of the attackers were dead. American deaths numbered eleven hundred. Such were the enemy losses that the Viet Cong ceased to be a factor in the war. After Tet the United States was fighting the North Vietnamese Army.

One of the lengthier battles of the Tet Offensive took place at Hue, the old imperial capital of Vietnam. NVA and VC troops initially took control of the city and were thrown out only after fierce fighting, often door to door, by U.S. marines and ARVN troops. Lest anyone think that the Communists were simply freedom-loving Vietnamese seeking to reunite their country, it should be noted that while occupying Hue the Communists rounded up 2,810 individuals they didn’t like and summarily executed them.

Atrocities, however, were not just the purview of the Communists. The U.S. Army also stepped over the line of civilized behavior. In March 1968, a small group of American infantry entered the village of My Lai and massacred more than two hundred civilians. At first the army attempted to cover up the incident. Eventually the truth came out and several officers were disciplined (though not harshly). Rarely have soldiers in American uniforms so disgraced themselves and the army in which they served.

General Westmoreland saw Tet as an American victory. He was wrong.

Shocked by the magnitude of the offensive, the American public considered Tet a disaster. Americans had been led to believe that the war was going well, that the end was in sight. Yet here was the enemy with strength assaulting targets all across South Vietnam. Particularly damaging were the reports and photographs of the VC attack on the embassy grounds. Nineteen VC sappers blew their way into the ambassador’s compound (but never reached the embassy itself). All nineteen were killed, as were several Americans. The repercussions of this attack and of the Tet Offensive in general were enormous. American support for the war plummeted.

Without this support, Lyndon Johnson could not maintain the course he had charted. He thus took a series of steps that drastically altered the military landscape in Vietnam as well as the political landscape in Washington. He turned down General Westmoreland’s request for 206,000 additional troops. He reduced the pace of Rolling Thunder. He convened a group of “wise men” to advise on how to proceed (they recommended he de-escalate the war effort—which he did). He initiated peace talks with the North Vietnamese. And, most dramatically, he announced in a televised speech to the nation on March 31, 1968, that he would not seek reelection.

Tet was a turning point. It caused the United States to back away from the war in Vietnam and forced an American president into retirement. In Hanoi the regime no doubt rejoiced. Total victory, they believed, was within reach.

***

One year after the start of the Tet Offensive, the United States had a new president. This was Richard Nixon, who soon appointed Dr. Henry Kissinger as his National Security Advisor. Together, they made a formidable team. Both were smart, tough, and devious, characteristics that would prove useful in dealing with the North Vietnamese. Their overriding goal was to establish a new balance of power, one in which America played a key role in making the world safer and more prosperous. This meant reaching an accommodation with Communist China and, via the Strategic Arms Limitation Treaty, with the Soviet Union. The situation in Vietnam they saw as an obstacle to achieving this goal, so they embarked on an effort, often secretly, to bring American involvement in Vietnam to a close.

The president knew he had to bring about the withdrawal of U.S. troops, but he wanted to do so in such a way that America’s honor was intact. This involved ensuring that a viable government of South Vietnam remained independent of the north. It meant also that he secure the release of the American prisoners held captive in Hanoi.

Most of these POWs were aviators, shot down during Rolling Thunder or later air raids. They numbered a little less than six hundred and constituted an important negotiating chip held by the Communists, who skillfully exploited the desire of the Americans to have these men returned. Their release was a political necessity for any diplomacy Nixon and Kissinger were to undertake.

Ensconced in the White House, the president embarked on four initiatives regarding Vietnam. The first was to begin, and then continue, the withdrawal of troops. By the end of 1969 some one hundred thousand soldiers had left. The second step was to build up the armed forces of South Vietnam to such an extent that they could survive once U.S. forces had departed. Consequently, tons and tons of military equipment were dispatched to the ARVN and to the South’s fledgling air force. Next, Nixon had Kissinger begin secret discussions with the North Vietnamese aimed at bringing an end to the conflict. The National Security Advisor went to Paris for these talks, but little was accomplished, for neither side was willing to make concessions the other considered essential. The fourth initiative was military in nature. Despite his Quaker upbringing, Nixon was no dove. He ordered the air force to strike the NVA hard and to strike it often.

One weapon the president wished the air force to employ more forcefully was the B-52. This impressive airplane could carry a large number of bombs, far more than either a Phantom or an F-105. Moreover, the plane had electronic devices on board that helped shield it from enemy missiles. Used extensively in Vietnam, the first B-52 mission took place on April 11, 1966. B-52s were employed tactically hitting targets in the south. They had not been sent north to Hanoi and Haiphong.

On March 18, 1969, Nixon ordered the big bombers to strike NVA troops and supply depots in Cambodia. Hanoi’s forces had long used as a sanctuary Cambodian territory adjacent to South Vietnam. This, of course, violated the country’s neutrality. They also had used the Cambodian Port of Sihanoukville on the Gulf of Siam as a major link for transporting supplies. Lyndon Johnson had denied his generals permission to attack these NVA enclaves. Richard Nixon had no such reservations. He sent the B-52s into action. Nixon kept these attacks secret. Not kept hidden was his next move: he ordered American ground troops to raid NVA bases in Cambodia. Some ten thousand U.S. soldiers joined five thousand ARVN troops in the attack. They killed a fair number of the enemy and destroyed large quantities of supplies, but they did not, as hoped, eliminate the NVA’s presence.

The invasion into Cambodia lasted from April 29, 1970, through June 30 of that year. Militarily, the raid made sense. But at home it created a political firestorm. Why, asked Mr. Nixon’s critics, at a time when the United States was reducing its role in Vietnam, did the army launch a new major offensive against a neutral nation? Students in particular objected. Many protested, some violently. As a result, a total of six students at Kent State University and Jackson State College were killed when fired upon by National Guard troops called out to restore order.

By the end of 1970, approximately 280,000 American soldiers remained in Vietnam. While a large number, it was far fewer than had served when U.S. troop levels peaked in 1969. Clearly, President Nixon was bringing the troops home. As their number decreased, so did their activity. In 1971, for example, General Creighton Abrams, who had replaced Westmoreland as commander of U.S. forces in Vietnam, conducted not a single major ground operation. American aircraft still flew combat missions, but on land the G.I.s no longer were on the attack.

Wisely, Richard Nixon believed the North Vietnamese would respect only force. So when the ARVN struck Communist bases in Laos (like Cambodia, an allegedly neutral state) he ordered U.S. air assets to support the South Vietnamese. No American ground troops were permitted to participate. The operation was called Lam Son 719. Involving nine thousand ARVN troops, it began on February 8, 1971. At first they did well. But soon outnumbered, they fell back, many in disarray. On both sides casualties were heavy. As an indication of the ARVN’s readiness to fight on its own, Lam Son 719 was not encouraging.

One positive outcome of the ARVN attack into Laos was to delay the invasion of South Vietnam, planning for which was under way by the NVA. Making such an invasion possible, the Soviet Union had re-equipped Hanoi’s army. No longer a lightly armed guerilla force, by early 1972 the NVA was a powerful and well-trained conventional army. It possessed large numbers of tanks, trucks, artillery pieces, and the like. With such a force North Vietnam reasoned it could at last crush the regime in the south. After all, by the spring of 1972, when the invasion began, U.S. troops mostly were gone from Vietnam and, as importantly, so were American aircraft.

***

The invasion began on March 30, 1972. Employing two hundred thousand troops, the NVA first struck across the DMZ, aiming for Quang Tri. Then, from Laos, they attacked in the Central Highlands, targeting the town of Kontum. Not wishing to exclude southern Vietnam, the NVA also attacked in the provinces northwest of Saigon. Known to Western historians as the Eastertide Offensive, the invasion was planned by Vo Nguyen Giap, Hanoi’s army chief who had triumphed at Dien Bien Phu. Massive in scope, it also was ferocious in character.

Despite having half a million men under arms, the South Vietnamese army was thrown back, in all three sectors. While several ARVN units performed well, many did not, repeating a pattern all too familiar to U.S. advisors. As the NVA troops progressed, their commander was confident of victory.

General Giap, however, had not reckoned on Richard Nixon.

Responding to the invasion, the president decided to assist the South Vietnamese. Sending in U.S. ground troops was not politically feasible, so Nixon turned to one of America’s most potent assets: airpower. He ordered air force and navy pilots back into combat. In one of his more memorable comments, Richard Nixon said, “The bastards have never been bombed like they’re going to be bombed this time.”

The U.S. aerial response to the Eastertide Offensive was code named Linebacker. In numbers alone the operation was impressive. From the Philippines and Guam, from Korea and Japan, and from airfields in the United States, aircraft returned to their bases in Thailand and South Vietnam. Indicative of the scale of the response, 168 airborne tankers participated in the campaign. Adding to Linebacker’s punch were the B-52s, which flew 6,038 sorties attacking targets in the south. Tactical aircraft too were part of the effort: F-4 Phantoms headed north to targets well above the DMZ, as did naval aircraft from the U.S. Navy’s aircraft carriers. To illustrate Nixon’s determination to pound the North Vietnamese, targets around Hanoi and Haiphong, previously off-limits, were now subject to attack. As one historian of the Vietnam War, Dave Richard Palmer, has written, “Linebacker was not Rolling Thunder—it was war.”

In first blunting and then halting the NVA, America’s intervention proved decisive. NVA troops, pounded from the air, gave ground and, eventually, withdrew. Battles, however, took place for a period of six months. Quang Tri, for example, which the Communists had seized, was liberated only in September. When the fighting finally ceased, the NVA had suffered one hundred thousand casualties (a number that seemed to disturb Hanoi not at all) and gained little ground. Clearly, the invasion had failed. It’s architect, Vo Nguyen Giap, was quietly replaced.

As American airpower was demonstrating its effectiveness, the president’s National Security Advisor was in Paris attempting to cut a deal with the North Vietnamese. By November, Dr. Kissinger had announced that the two sides were close to an agreement. But at the last minute the talks broke down. The Americans concluded that the Vietnamese simply were stalling for time, while the north saw revisions to the agreement Kissinger was seeking on behalf of the South Vietnamese government as duplicitous. Regardless of which side was to blame, the talks were deadlocked. No agreement had been reached. Frustrated, Henry Kissinger returned to Washington to consult with Mr. Nixon.

Angry with the North Vietnamese, Richard Nixon once again turned to airpower. In an effort to get the north to sign an agreement, the president ordered his air commander to pulverize Hanoi and Haiphong. And this time the B-52s, symbol of American aerial might, would not be limited to tactical strikes in South Vietnam. For the first time, they were to be sent north. The president wanted the U.S. Air Force to dispatch the big bombers to the two cities and hit them hard. The goal was not to kill civilians (thus, some targets were still off-limits), but to level practically every conceivable military installation.

What followed is referred to as the Christmas Bombings. President Nixon and the air force called it Linebacker II. For eleven days, beginning on December 18, 1972, the B-52s struck the heart of North Vietnam. At first, the Vietnamese put up a stout defense, firing SA-2 missiles at the planes. These brought down fourteen of the bombers. Another B-52 was lost to MiGs, bringing the total number of B-52s destroyed to fifteen. Despite these losses, the air campaign succeeded. Having fifteen thousand tons of bombs dropped on them convinced leaders in Hanoi to resume the peace talks.

Negotiations began again on January 8, 1973, and agreement quickly was reached. That the north had no intention of honoring the terms of the agreement it had signed made little difference. Thanks to Richard Nixon and Henry Kissinger, the United States had found a way to extricate itself from what had been a long and bloody conflict.

***

Late in February of 1973 a U.S. Air Force C-141 transport plane lifted off the runway at Hanoi’s airport. Aboard were former American POWs, now free. At least one of the conditions insisted on by President Nixon, that Americans held captive be released, had been achieved. The other condition, that South Vietnam be allowed to remain independent of the north, was not to be realized.

Almost immediately after the agreement in Paris had been signed, the regime in Hanoi began planning another invasion. Aided greatly by having thousands of troops already in the south, troops that, by the terms of the Paris Accord, they did not have to withdraw, the Communists assembled men and military equipment for the attack. This took well over a year. By the spring of 1975, they were ready.

The attack began in March. Richard Nixon had pledged to the South Vietnamese that should the north again attack, the United States would come to its defense, as it had during the Eastertide Offensive. But in 1975 Nixon no longer was president. His successor, Gerald Ford, wished to render assistance. However, restrained by an American public tired of the conflict and by the newly enacted War Powers Act that limited presidential discretion in terms of military action, he was unable to do so. Thus Ford allowed North Vietnam’s blatant violation of the Paris Accord to go unanswered. This time no American aerial armada would return to Vietnam.

In 1975, the army of South Vietnam still had many men under arms. While underequipped due to cutbacks in U.S. military assistance, the ARVN was battle-tested and seemingly capable of stopping the invaders. Most American commanders thought the army would put up a good fight.

They were wrong.

In perhaps one of the more dismal performances by any army in the twentieth century, the ARVN, when confronting the NVA, quickly collapsed. True, some units fought well, but overall, southern forces easily gave way to the troops of the north. When NVA tanks broke into Saigon’s presidential palace on April 30, 1975, the war was over. South Vietnam, a country the United States, with its blood and treasure, had tried to keep afloat, ceased to exist.

The cost of America’s failure was high. The war’s memorial in Washington, D.C., a stark but compelling black wall, lists the names of 58,261 men and women who died in Vietnam. Their sacrifice appears to have been in vain.

Why did the United States lose the war in Vietnam?

Losing a war requires a definition of winning. In the case of Vietnam winning meant convincing the North Vietnamese to stop its efforts to overthrow the government in Saigon. Said another way, winning for the United States meant securing the independence of the South Vietnamese, enabling their government to be both sustainable and free. Unfortunately for America, Rolling Thunder and the two Linebacker campaigns did not persuade the regime in Hanoi to back off. Neither did the presence of more than half a million American troops.

But the underlying cause of America’s defeat, its first in a military history generally characterized by victory, was a matter of political will. The regime in Hanoi was more determined to succeed, more willing to persevere, more accepting of casualties than its counterpart in Washington. Lyndon Johnson and Richard Nixon led a country that soon tired of the war in Vietnam. The United States lacked the stomach to make the sacrifices required. The Democratic Republic of Vietnam, based in Hanoi, did not.

Could the United States have won the war in Vietnam?

Whether the United States could have won is, of course, a matter of conjecture. Academics such as George Herring, author of America’s Longest War, believe the war was unwinnable. They point to the lack of political cohesion among the South Vietnamese, to the inept leadership of the ARVN, and to the American public’s unwillingness to accept casualties. These academics make a strong case.

But so do those who believe victory was possible. These tend to be military men, who argue that the war was fought incompetently, especially from 1965 to 1967, when the North Vietnamese were not as strong as they became in later years. These men note that had U.S. political leaders done what the country’s military commanders advocated, the outcome would have been different. The American commanders in Vietnam wanted to hit Hanoi and Haiphong early in the war. They wanted to strike the Communist sanctuaries in Laos and Cambodia. They wanted to land marines halfway up the coast of North Vietnam, thereby splitting the country in half. Had the United States taken these actions, military leaders contend, the Communists would have been forced to halt their aggression in order to focus on the more immediate threat to Hanoi.

Whom to believe? The military men are correct in stating that America fought the war in a limited way. Why? Because as this narrative has stated, Lyndon Johnson did not want a repetition of the Korean experience, where hordes of Chinese soldiers crossed the border and crushed an American army. Whether the Chinese would have done so in Vietnam cannot be known for certain. Had the Chinese intervened, however, it is not unreasonable to believe that America’s armed forces would have been able to contain them.

Yet the academics too have a valid point. The government in South Vietnam was not effective and the people there lacked political cohesion, democratic traditions, and allegiance to the state. But with more—and smarter—persistence on the part of the United States, could not a sustainable government in the south have been established? Probably so.

How then to answer the question? Could the United States have won?

America’s war in Vietnam, this author believes, could have been won early on, by the more forcible application of military might. But victory was achievable only early on in the conflict, before the NVA gained in strength and before the American people grew weary of body bags. As it is now, the United States was then a military superpower, but its citizens’ willingness to accept battle deaths was and is such that victory must be quick, before casualties mount. Otherwise, the country cedes the outcome to its opponent.