11

IRAQ

2003–2010

On March 20, 2003, American and British troops, staging from Kuwait, invaded Iraq. Superbly equipped, these troops constituted a small but lethal military force. As they pushed through the sand berms at the Iraqi-Kuwaiti border, the invaders had two simple objectives: they were to remove Saddam Hussein from power and bring an end to his Baathist regime.

For years, as the rulers of the country, Saddam and his thugs had terrorized the people of Iraq, and twice they had brought war to the Middle East. By 2003, armed with chemical weapons and having both the capability and desire to develop nuclear devices, Saddam’s Iraq posed a threat to the stability of a region critical to countries dependent on oil. Most leaders of the worlds’ nations seemed content to tolerate Saddam. One leader did not. This was George W. Bush, the president of the United States.

At the urging of the British prime minister, Tony Blair, and of his own secretary of state, Colin Powell, Mr. Bush had gone to the United Nations to seek authorization to move against Saddam. The Iraqi leader had ignored numerous U.N. resolutions aimed at correcting his country’s unacceptable behavior, particularly in regard to nuclear weapons. Increasingly, the international body was receptive to the employment of force. In September 2002, the president had told the U.N. that Saddam was a threat not only to peace, but also to the credibility of the United Nations itself. The next month, the U.N. Security Council unanimously adopted Resolution 1441, which threatened serious consequences if Iraq did not meet the U.N.-imposed obligations. When Saddam continued to defy the U.N., the American leader, who previously had labeled Iraq as part of an “axis of evil” (along with Iran and North Korea), decided to take action. France, with substantial economic ties to Iraq, objected. Dominique de Villepin, the French foreign minister, argued that before military force was used another resolution was required. The United States disagreed. To George Bush and his vice president, Dick Cheney, 1441 was more than sufficient. Having been told by American, British, and other intelligence agencies that Saddam was building nuclear weapons, they believed the time for debate and diplomacy had ended.

In addition to the United Nations, the American president also sought approval for the use of force from the American people. And he got it. In October 2002 both houses of Congress passed resolutions supporting military intervention. In the Senate the vote was 77–23. In the House of Representatives it was 296–133. In effect, the United States had voted to go to war.

On March 17, 2003, the president issued an ultimatum to Saddam to leave Iraq within forty-eight hours. A refusal to do so, he said, would result in armed conflict “at a time of our choosing.” Saddam stayed put. Three days later, American and British tanks crossed the border.

***

In overall command of the forces deployed to oust Saddam was Tommy Franks, a four-star general in the U.S. Army. Officially, Franks was in charge of Central Command. This was one of six joint commands the United States had established to cover large geographic areas. Encompassing nineteen countries, Central Command at the time had two principal concerns. One was Afghanistan, where U.S. troops were at war with Islamic fundamentalists allied with those responsible for the 2001 terrorist attacks of September 11. The other was Iraq. After the Gulf War, despite two no-fly zones and U.N. sanctions, Saddam Hussein was in Baghdad, still in charge. He continued to repress Iraqi citizens and to threaten the stability of the lands under Central Command’s purview.

As chief of the Command, General Franks had senior officers reporting to him. One of these was Lieutenant General David McKiernan, who was in charge of all ground operations. McKiernan would lead the effort to unseat Saddam. With input and approval provided by Tommy Franks, McKiernan devised a detailed plan of battle. The American came up with an audacious scheme, which was given the name Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF).

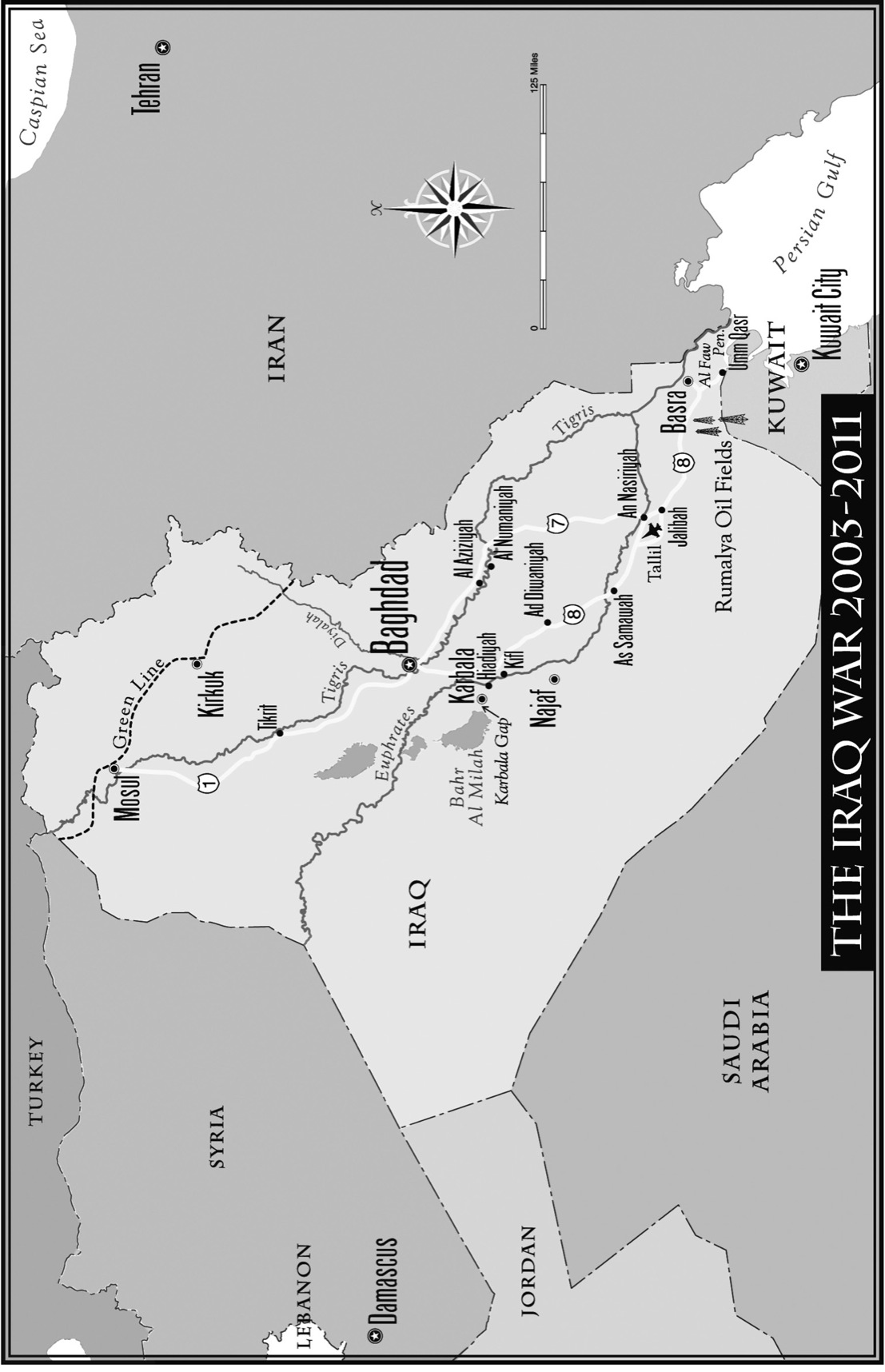

His plan called for two powerful armored strike forces to move quickly north to Baghdad. One of the forces, comprising several U.S. Army divisions, would approach the Iraqi capital via the Euphrates River. The other, made up of U.S. marines and located to the east, would advance along the Tigris. The two armored units would surround Baghdad, sealing off the city, and then prevent enemy movements into and from the city. The plan emphasized speed and the need to avoid costly battles in the towns along the way. These towns would be sealed off but not fought over and occupied. American casualties thus would be kept low and the war not turned into a lengthy conflict. The hope was that if Baghdad were rapidly cordoned off, Saddam and his regime would collapse.

Other elements of the plan envisioned British troops seizing Basra and the Al Faw Peninsula, including the port of Umm Qasr. Additionally, U.S., British, and Australian Special Forces would operate in the Iraqi western desert, shutting down missile sites and keeping enemy troops away from Baghdad. Other Special Forces would work in the northern part of Iraq both aiding and keeping in check Iraqi Kurds who had their sights set on the oil fields near the cities of Mosul and Kirkuk.

Of course, America’s war plan called for air strikes. These would be extensive and involve U.S. naval aircraft as well as those of Britain’s Royal Air Force. In the Gulf War airpower had played a significant role, and it would do so again in this conflict. This time around, there was to be a major difference. Franks and McKiernan wanted no preliminary air campaign as had occurred in the 1990–1991 conflict. They believed lengthy air strikes prior to ground-level attacks would give advance warning to Saddam and his generals, enabling them to better prepare their defenses. The two American commanders thought that by attacking first with soldiers and marines they would surprise the Iraqis, throw them off balance, and deliver a shock to Saddam’s political and military infrastructure.

One element of the plan put together by Tommy Franks and David McKiernan was never to be realized. This called for a strong ground force to strike into northern Iraq from Turkey. Such an attack would have required Saddam to fend off American forces from several directions. This made sound military sense, but unfortunately for the Americans, the Turks objected and refused access to their territory. The result was that no attack occurred from the north.

During Operation Iraqi Freedom David McKiernan directed several U.S. Army units that, taken together, were designated as Third Army. The unit’s name was rich in American history. In June of 1944, the Third Army had been established in Normandy, soon after the D-Day landings. Its commander was George Patton, who, utilizing the speed and firepower afforded by its many tanks, defeated German forces as the army drove through France. Patton’s campaign began as part of Omar Bradley’s Operation Cobra, which saw the Americans break out of the French bocage and begin the drive to the German frontier. With a sense of history and the desire to replicate Third Army’s success, General McKiernan named his ground attacks Operation Cobra II.

Throughout the planning process and the campaign itself, there was one scenario that deeply concerned the Americans. This was the possibility that as they drew near to Baghdad, Saddam would employ weapons of mass destruction (WMDs), principally chemical weapons and possibly biologicals, in order to halt the invaders. Saddam had employed the former against his own people, so why would he not use them against the Americans? In response, all Coalition troops in the region were issued protective gear. Moreover, special units, including several from Germany and the Czech Republic, were deployed to detect the presence of various toxins. While no doubt Saddam had been warned not to use the WMDs, U.S. leaders were fearful that the Iraqi leader, concluding that he personally had little to lose, would target the approaching Americans with the deadly devices.

Among the American leaders concerned by an Iraqi deployment of such weapons was Donald Rumsfeld, President Bush’s secretary of defense. Rumsfeld was a strong advocate of removing Saddam Hussein by force. He also, during his tenure at the Pentagon, was attempting to remake the American military, especially the army. The secretary believed the U.S. Army needed to field units that emphasized speed, lethality, and new sophisticated tools of warfare that only America could bring to the battlefield. Rumsfeld wanted his generals to gain victory through technology, mobility, and firepower. Thus, when Tommy Franks first presented him with a plan for invading Iraq that called for 450,000 troops, Rumsfeld said no. The secretary wanted—and obtained—a much smaller strike force. When General McKiernan’s soldiers and marines attacked on March 20, they numbered only 145,000.

When Operation Cobra II began, Apache attack helicopters and the ever-accurate American artillery struck the Iraqi early-warning sites along the Iraqi-Kuwaiti border. Putting these out of commission enabled McKiernan’s troops to surprise the Iraqis, especially since no air campaign had signaled the war’s start.

In fact, the war with Iraq did not begin with the ground attacks of March 20. The day before, America’s Central Intelligence Agency received what it considered reliable information that Saddam Hussein would spend the night at a compound called Dora Farms, located in an eastern suburb of Baghdad. President Bush made the decision to strike the compound in the hope of killing the Iraqi leader. Although cruise missiles were launched as part of the strike, the principal attack was delivered by two F-117 Nighthawks. These were slow but stealthy aircraft, each armed with two large, precision bunker-busting bombs. Arriving over Baghdad just before sunlight (they flew combat missions only at night), the planes released their deadly payloads and destroyed Dora Farms. But Saddam was not there, so the mission, executed with considerable skill, went for naught. Saddam, however, took notice. He ordered a retaliatory strike sending a Chinese-built sea-skimming missile into Kuwait. It landed near the U.S. Marine Corps headquarters in that country, but caused no damage.

Between March 21 and April 3, 2003, the Iraqis launched seventeen missiles at the invading Americans. Of these, eight either crashed prematurely or targeted nothing of value. The remaining nine were intercepted by U.S. Army Patriot missiles. The Patriot was an air defense system in which the Pentagon had invested heavily. Earlier models of the missile had performed poorly in the previous war against Iraq. This time, apparently, the Patriots earned their keep.

As the troops under David McKiernan’s command advanced toward Baghdad, they were aided greatly by the firepower of British and American warplanes. Because Iraq’s air force made no effort to interfere, these aircraft enjoyed air supremacy. And, given that Saddam’s ground-based air defenses had been weakened by two no-fly zones put in place at the conclusion of the Gulf War, the American and British pilots operated in an environment that kept losses extremely low.

Tommy Franks and his air commanders planned an opening round of air strikes—referred to at the time as “shock and awe”—that would signal to the Iraqis that this time, the gloves were off. Significantly, however, a number of normally legitimate targets were off-limits. Bridges were kept intact because the Central Command chief wanted them available for use by McKiernan’s forces once they reached the city. Power plants also were left alone. Their output would be needed once the war was over. The goal of the war, after all, was the removal of Saddam and his regime, not the obliteration of Iraqi cities and towns. This restraint by General Franks served another goal as well. It helped reduce civilian casualties. Critics of the American military seek to portray it as insensitive to the loss of life. In fact, the opposite is true. Such was the concern over the death of Iraqi civilians that any target the U.S. Air Force wished to hit had to have the personal approval of the secretary of defense should estimated civilian deaths number thirty or more.

The scale of the initial air strikes can be seen in the fifteen hundred sorties flown during the first four days (a sortie is one plane flying one mission). Aircraft taking part in the aerial offensive flew from bases nearby in Kuwait and Qatar and as far away as Diego Garcia and the United Kingdom. There even were missions by American aircraft based in Missouri. During the entire twenty-three days of air attacks 36,275 sorties were flown, an astonishing number and one that reveals the extent of the aerial assault. Keeping the airplanes’ fuel tanks full required an enormous effort as modern military aircraft are notorious gas guzzlers. Through April 11, tanker planes, via in-flight refueling, delivered more than forty-six million gallons of jet fuel.

Many of the strike aircraft operating over Iraq were deployed not in a strategic sense, but tactically, in missions designed to assist ground forces. These planes alerted McKiernan’s troops to the nearby presence of enemy troops and, more important, pounded Iraqi tanks and bunkers that stood in the way of advancing Americans.

***

Early in the advance north the U.S. 3rd Infantry Division, one of General McKiernan’s principal fighting units, took control of an Iraqi airfield southwest of An Nasiriyah. The airfield, Tallil, would become an important logistics base as the Americans continued their drive toward Baghdad. An Nasiriyah, a town of approximately three hundred thousand, stood astride the Euphrates River. For the Iraqis, it could be a place to intercept enemy troops and their supplies. For the Americans, securing An Nasiriyah was essential if the invasion was to proceed as planned. McKiernan wanted his soldiers to seal off the town and avoid a slugfest that would slow the advance. Having done so, his troops were to turn responsibility for An Nasiriyah over to the marines, who, while leaving a sufficient number of troops to control the town, would cross the Euphrates at that point and head north to the Tigris, thus approaching Baghdad from the east.

McKiernan’s plan was executed. The marines took charge of An Nasiriyah and the 3rd Infantry moved north to As Samawah. In both towns, however, U.S. forces received a nasty surprise. They had been told Iraqis in the southern part of the country, being Shiite, would welcome American troops. That turned out not to be the case. Moreover, the soldiers and marines confronted an enemy they had not anticipated. This was the fedayeen. They were fanatical Muslims, full of hatred for America. Many were Syrians, paid by Saddam. Poorly trained and equipped with only light weapons, they made suicide attacks against the American armored vehicles. That they did so demonstrated a certain kind of courage. That they murdered Iraqis they disapproved of, and fired from within mosques and schools, suggested their rules of combat differed from those of their opponents.

The 3rd Infantry soldiers arrived at As Samawah on March 23. They were warmly greeted—by enemy rocket-propelled grenades, mortar rounds, and machine gun fire. The result was a two-day-long firefight that left a considerable number of the defenders no longer alive. Among the highlights of the battle was the use by the fedayeen of innocent women and children as human shields.

Next stop for the Americans was the city of Najaf. It sat on Highway 8 and, like An Nasiriyah and As Samawah, had to be contained in order for supplies to reach the advancing combat troops. The fighting at Najaf was brutal. It began on March 24 and lasted for four days. U.S. troops employed the full array of their capabilities—tanks, artillery, and air strikes. The enemy, Iraqis as well as the fedayeen, were outmatched but fought hard. They would fire their weapons and then, more often than not, be killed. When the battle was over, approximately one thousand of them were dead.

About this time Mother Nature intervened. A massive sandstorm struck the entire area. Called a shamal, the storm combined high winds, sand, and rain. It blinded soldiers, kept helicopters on the ground, and made difficult simple tasks such as walking, eating, and trying to clean one’s rifle. However, American artillery and the air force’s precision-guided weapons were less affected. Iraqi commanders, believing the invaders were as blinded as they were, decided to reposition their troops, expecting the shamal to hide their movements. It did not. American high-tech bombs and artillery shells found the Iraqis and inflicted serious damage.

The sandstorm coincided with a pause in the American advance. After several days of hard fighting, little sleep, and a trek of many miles, McKiernan’s soldiers, principally the 3rd Infantry Division, were in need of rest. Moreover, they were running short of supplies. So the general ordered a pause in the action.

The time was well spent. Recognizing the requirement for his now lengthy supply lines to be secure, McKiernan directed two of the U.S. Army’s most elite units, the 82nd Airborne Division and the 101st Air Assault Division, to relieve the 3rd Infantry at As Samawah and Najaf. Their task was to ensure the flow of supplies north and to seize control of both towns. This they did, though not without a fight.

No longer tied down at As Samawah and Najaf, the 3rd Infantry Division was now at full strength. It would spearhead the army’s drive into Baghdad. The question was how best to have it move on the Iraqi capital. Once again, the pause was useful. McKiernan and his senior commanders used the time to fix on a plan for the attack. For America’s army, this meant a series of feints to confuse the Iraqis and then a Patton-like push through a slice of Iraq’s territory known as the Karbala Gap.

***

America was not the only country to invade Iraq. The United Kingdom also participated in the campaign to remove Saddam Hussein. The British contribution was substantial. It numbered forty-six thousand service personnel. Among these were sailors who manned thirty-three warships the Royal Navy deployed to the Persian Gulf. The ships included HMS Ark Royal, Britain’s largest warship, and six small mine-clearing vessels. The latter performed the essential task of clearing the narrow waterways to Basra and Umm Qasr, Iraq’s two ports.

Another British warship deserves mention by name. This is HMS Turbulent, a nuclear attack submarine. When sent to the Gulf, she had not seen England for more than ten months, having traveled fifty thousand miles, forty thousand of them underwater. Turbulent’s contribution to the campaign was a salvo of Tomahawk cruise missiles, launched from beneath the sea, that hit their targets in Iraq miles and miles away.

On March 20, 2003, British land forces took part in the opening assault of Operation Iraqi Freedom. Their objectives were the Rumaila oil fields and the oil terminals of the Al-Faw Peninsula. American and British commanders feared the Iraqis would torch the former and open the spigots of the latter, thereby causing environmental harm and economic loss. With assistance from U.S. marines both objectives were met. But the effort was not easy. The British troops encountered considerable opposition, especially from Iraqi tanks and artillery.

We go to liberate not to conquer. We will not fly our flags in their country. We are entering Iraq to free a people, and the only flag which will be flown is their own.

So spoke a British army officer to his troops prior to the start of the war. Having secured the oil fields and occupied the Al-Faw Peninsula, the twenty thousand soldiers comprising Britain’s assault force advanced on Basra. With a population of 1.5 million people, this was Iraq’s second largest city and key to the southern region of the country. British troops reached the outskirts of Basra on Day Two of the war. But they made no attempt to enter. Instead, they cordoned off Basra, and conducted raids into the city. In turn, Iraqi forces more than once attempted to break out, often employing T-55 tanks. The British were equipped with their own tanks, the first-rate Challenger 2, and beat back the Iraqi forces.

On March 30 the British staged an attack of their own, at a suburb of Basra called Abu al-Khasib. In a nineteen-hour firefight against numerous Iraqis, they carried the day, killing seventy of the enemy and taking three hundred Iraqis prisoner. The next day, in another fight, twenty-five Iraqi tanks were put out of commission, as were two hundred Iraqi soldiers. Soon thereafter resistance in the city melted away, and the British occupied Basra.

What they found was a city whose population was in dire straits. Food was scarce, medicines were in short supply, and city services were in need of fixing. Moreover, Saddam’s men, many of them fedayeen, had exercised a firm control, killing those Iraqis they deemed insufficiently loyal.

Responding to the challenges, the British shipped humanitarian aid to the Iraqis. This had to be delivered by sea, which is why Umm Qasr had been seized. British troops had captured the port at the end of March, though not without a fight. During the battle the British defense minister described the Iraqi port as similar to Southampton. To which a British commando replied, “It’s not at all like Southampton: there’s no beer . . . and they’re shooting at us.”

***

The United States Marine Corps is rightly proud of its capability to conduct amphibious operations. In the war to remove Saddam Hussein, the Corps would play an important role, but its role was similar to that of the army’s 3rd Infantry Division. The marines would conduct a land campaign. There would be no assault from the sea.

For the campaign, the American marines deployed a substantial portion of their overall strength. Slightly more than sixty thousand marines took part in Operation Iraqi Freedom. At 8:30 P.M. local time on March 20, 2003, pursuant to David McKiernan’s plan, the marines drove through the sand berms and entered Iraq.

Initial resistance was light, although the first American to be killed in combat was a marine. Along with the British, the marines’ initial task was to secure the Rumaila oil fields, and then they were to proceed northwest to An Nasiriyah. Once there, they were to relieve the army’s 3rd Infantry Division and take control of the town. The latter task was necessary because at An Nasiriyah, as noted above, the marines were to cross the Euphrates River and then advance along Highways 1 and 7 to the Tigris. All this they accomplished. But it was at An Nasiriyah that the fedayeen made their debut. Looking like civilians (because they were civilians), these irregulars were Islamic fundamentalists eager to kill Americans. In combat with the marines and McKiernan’s soldiers, the fedayeen posed a serious threat. Moreover, they seemed willing, even anxious, to die.

There were three bridges at An Nasiriyah that the American marines needed to control. Because the city was largely Shiite, the U.S. forces expected only minor resistance. But the presence of the fedayeen along with Iraqi army troops turned An Nasiriyah from the anticipated cakewalk into a bloody brawl that lasted for more than a week. When the battle concluded, the bridges, and the city, belonged to the Americans. But the cost was high: nineteen U.S. marines were dead and fifty-seven were wounded. Their opponents, however, suffered far greater losses. The marines believe they killed two thousand of their enemy.

The marines fighting at An Nasiriyah were a unit independent of the main marine strike force that eventually would reach Baghdad. With some five thousand men, the unit was called Task Force Tarawa. The name came from one of the Corps’s more brutal (though successful) battles of the Second World War, Tarawa being a once-obscure island in the Pacific. The fight for the bridges at An Nasiriyah was not equal in scale to that of Tarawa, but like the 1943 fight, it has earned a place of honor in the history of the Corps.

Unfortunately for the Americans, the first U.S. troops to enter An Nasiriyah were neither the marines of Task Force Tarawa nor the 3rd Infantry soldiers they had relieved. The first troops in the city belonged to the U.S. Army’s 507th Maintenance Company. These were support soldiers, driving supply trucks to combat forces farther north. Their convoy had split into sections, one of which, with sixteen vehicles and thirty-three soldiers, arrived at An Nasiriyah on the morning of March 23, 2003. There, they were to turn left and proceed northwest. Instead, they continued straight and drove into the Iraqi city. After crossing several bridges they realized their mistake, turned around, and retraced their steps. This took them down a two-mile road later dubbed “Ambush Alley.” The first time through, the Iraqis had just stared, surprised by the absence of American weaponry. The second time, when the Americans returned, the Iraqis and their fedayeen allies opened fire. The result was a mini-massacre. Eleven soldiers of the 507th were killed. Six became prisoners of war (one of them a woman, Private First Class Jessica Lynch, who later was rescued).

March 23 was a day the Americans would like to forget. That day the 507th Maintenance Company was hammered along Ambush Alley. Then several marines were killed in an effort to secure An Nasiriyah. That same morning, the army’s vaunted Apache helicopters failed to perform as advertised in a strike against an Iraqi army division. On March 23, in executing the attack, an Apache crashed on takeoff, one was shot down, and the remaining thirty-two machines were heavily damaged. Compounding the failure, very little harm was done to the Iraqi unit.

The Americans experienced one further setback on March 23. Using the Patriot air defense missile system, they inadvertently shot down a British warplane, killing both crew members. So, most appropriately, the U.S. Army’s account of Operation Iraqi Freedom calls March 23, 2003, “the darkest day.”

Once An Nasiriyah was under control, the marines were in position to start their drive to the Iraqi capital. One force of marines drove north along Highway 7. Another advanced to Ad Diwaniyah along Highway 1. They met at An Numaniyah, crossing the Tigris at that point. Task Force Tarawa was given the job of securing the ever-lengthening supply lines. This was no easy task as its area of responsibility equaled the size of America’s South Carolina. Supplies, of course, were vital to the advancing attack force. Marine requirements for food, ammunition, and fuel were high. Each day, supply trucks needed to deliver 250,000 gallons of gas to keep the combat vehicles moving. As the marines advanced, these trucks, starting their journey in Kuwait, had to travel some three hundred miles.

The terrain that the marines traversed was one of agricultural lands, laced with small rivers and canals. Unlike the army troops, the marines had little desert to deal with, for they fought largely on lands between Iraq’s two great rivers, the Euphrates and the Tigris.

They reached the latter, at An Numaniyah, on April 2. But it had not been an easy journey. Iraqi troops fought hard and the fedayeen were out in force. The marines moved forward in tanks, armored personnel carriers, and the ubiquitous Humvees. Artillery and Apaches provided protection. Nonetheless, ambushes were many and the marines took casualties.

As the marines got close to Baghdad, Iraqi resistance stiffened. Tanks and artillery were employed to stop the Americans. Near Al Aziziyah, forty miles south of the capital, an eight-hour battle took place, which Williamson Murray and Robert H. Scales Jr., in their book The Iraq War: A Military History, described as “the most significant battle against enemy conventional forces during the war.” Once again the Americans won the day. It seemed like nothing could stop the marines; at least the Iraqis couldn’t. But as the army’s history of the campaign states, “getting to Baghdad looked easier on the map than it was in practice.”

The marines arrived in the environs of Baghdad on April 6.. The next day, under fire, they crossed the Diyala River, a small waterway that flows into the Tigris River just east of the city. Using tanks, amphibious vehicles, helicopters, and artillery, the American force moved into the Iraqi capital, staying east of the Tigris. By then, many in the Iraqi military had taken off their uniforms and, to employ a phrase a number of observers later used, “melted away.”

The marines’ campaign had been a success. Starting at the Iraqi-Kuwaiti border, America’s maritime soldiers had fought their way to Baghdad. Skeptics would say they had faced a third-rate adversary. Perhaps, but this adversary was well armed and, more than once, fought tenaciously.

The campaign was not over when the marines crossed the Diyala. There would be several days of combat in the city itself before the marines were able to lay down their weapons. What they had accomplished no longer may be of interest to an American public tired of the quagmire Iraq became. But historians, at least some of them, may take note of the U.S. Marine Corps’ Iraqi campaign. One British observer, as reported by Murray and Scales, called it “one that should be taught in staff colleges for years to come.”

***

The American assault on Iraq in 2003 encompassed six separate military endeavors. These were mutually reinforcing and, in fact, constituted a single, integrated campaign. In no particular order the six were: (1) the U.S. marine advance to Baghdad via An Nasiriyah and the Tigris, (2) the British operations in the south, (3) the naval efforts from warships in the Persian Gulf, (4) the aerial strikes that so greatly aided U.S. and British ground troops, (5) the U.S. Army’s drive to Baghdad along the Euphrates River, and (6) Special Forces operations north and west of the Iraqi capital.

As noted earlier, Special Forces in Iraq had several tasks. They were to shut down Iraqi Scud missile operations, keep enemy army units in the north from reinforcing the defenses of Baghdad, and both assist and restrain the Iraqi Kurds who inhabited much of Iraq’s northern lands. When the war ended, the Special Forces had successfully carried out all three tasks.

The Kurds were an Islamic people who, while Iraqis, enjoyed semi-independence from Saddam’s regime. They lived north of what was called the Green Line. This was a one-hundred-mile-long line of demarcation, the south of which was controlled by Saddam. The Kurds had little love for the Iraqi ruler and, thus, welcomed the presence of U.S. Special Forces. Complicating an already complex political situation were the Kurds living in eastern Turkey. They wished, as did many of the Iraqi Kurds, to establish an independent Kurdish nation. This desire greatly upset the Turks. They saw in American support of the Iraqi Kurds the possibility of consequences that would lead to a new country, Kurdistan, part of which would be carved out of their own territory.

During late March and early April, the American Special Forces, augmented by regular U.S. Army troops and marines, and enjoying firepower delivered by American aircraft, defeated their Iraqi opponents on more than one occasion. At the same time they supported the Iraqi Kurds, providing weapons, medicines, and tactical advice.

Three specific military operations in the north were particularly noteworthy. The first, which began on March 26 and lasted four days, was a successful attack on an Iranian-backed group of al-Qaeda terrorists known as Ansar al-Islam. The Kurds detested this group and, with 6,500 men, supported by U.S. Special Forces and American airpower, assaulted their mountain strongholds, killing many of the terrorists.

The second operation was an all-American action. One thousand soldiers of the 173rd Airborne Brigade parachuted onto an airfield in the Kurdish-controlled portion of Iraq (this was the forty-fourth combat jump in the history of the U.S. Army). The next day, March 27, additional paratroopers were flown in, as were tanks and supplies, the latter for both the Americans and their Kurdish allies.

The airborne operation showcased U.S. military strength in northern Iraq. It also bolstered the morale of the Kurds and reinforced the incorrect belief held by the Iraqis that the Americans would employ paratroopers to seize Baghdad. That the brigade’s drop zone already had been secured by Special Forces did not detract from its value.

The third military operation that deserves mention took place early in April. At that time, U.S. Special Forces and the Kurds were preparing to attack Kirkuk. This city, two hundred miles north of Baghdad, and its environs were rich with oil reserves. Those who controlled the city controlled the oil. The Kurds were eager to seize Kirkuk. However, before the attack occurred, the Iraqi defenders left. The Kurds then occupied the city. For the Americans, this was unacceptable. It constituted a possible prelude to Kurdish independence, which, in addition to bringing about likely action by the Turkish armed forces, jeopardized the territorial integrity of Iraq. The latter possibility concerned the Americans, who, after all, had invaded Iraq to remove Saddam and his regime, not to dismember the country. The U.S. Special Forces acted immediately. Exercising both political skill and military muscle, they persuaded the Kurds to withdraw.

***

Once the great sandstorm—the shamal—had subsided, the U.S. soldiers that had reached Najaf were ready to move on Baghdad. The march “up country” was over. The time had come to first surround and then seize the Iraqi capital.

One issue Americans had to consider was where to cross the Euphrates River. Their commanders decided to do so in the narrow gap between the town of Karbala and the large lake to its east, Bahr al Milh. With Karbala just fifty miles south of Baghdad, McKiernan expected the Iraqis to put up a stiff resistance. And if Saddam was ever going to employ weapons of mass destruction, the American general assumed he would do so as they approached the Iraqi capital.

To confuse the Iraqis and to have their focus on somewhere other than the Karbala Gap, the Americans conducted a series of feints. These were five simultaneous attacks each of which McKiernan wanted Saddam to conclude might be the principal attack. One of the feints was at Hindiyah. Another was at Kifl, a town north of Najaf but east of the great river. Kifl was full of fedayeen who used it as a transit point for deployment farther south. The resulting battle in and around Kifl turned out to be more of a fight than the Americans had expected. But the outcome was similar to other battles in Iraq: U.S. troops carried the day.

The drive through the Gap began at midnight on April 1. Abrams tanks and Bradley armored personnel carriers led the way. Their immediate objective was the bridge at Yasir al-Khuder. This spanned the Euphrates and was just twenty miles from Baghdad. The Iraqis, who had repositioned troops away from the Gap in response to the feints, nevertheless fought hard. Using T-72s, Russian-built main battle tanks, and artillery, Saddam’s soldiers made a determined effort to halt the Americans. They failed, but punctured the belief now held by many that the Iraqi army was incapable of striking back.

By April 3, McKiernan’s troops were closing in on Baghdad’s main airport, which lay to the west of the city. The next day, a fierce battle took place as the Iraqis attempted to repel the invaders. When the fight was over, thirty-four T-72 tanks had been destroyed and many Iraqis killed. The Americans controlled the airport and, with the marines approaching the Diyala, the encirclement of Baghdad had begun.

To prevent Iraqi troops from either reinforcing or leaving the capital, McKiernan’s soldiers established five operating bases south and west of Baghdad. These also placed the Americans in position to take control of the city. Each of the five were named after an American professional football team. Thus, Objectives Bears, Lions, Texans, Ravens, and Saints ringed much of Baghdad. Objective Saints was an area where two key highways intersected. The Iraqis fought hard to keep the Americans from securing this pivotal location. Employing tanks and artillery as well as commandos, Saddam’s men attacked. But to no avail. The battle took place on April 3 and 4, and when it was over, Objective Saints was in American hands.

Throughout the war the news media covered the Americans’ advance. To make possible more accurate and extensive coverage, Secretary of Defense Rumsfeld permitted reporters to be embedded in U.S. combat units. These media personnel shared the hardships endured by the American troops. They also faced the dangers inherent when the shooting started. One of the embedded reporters was Michael Kelly of the Atlantic Monthly. He died during the attack on Baghdad’s airport, when the Humvee in which he was a passenger plunged into a canal, landing upside down.

While the American public and others were kept informed of the war’s progress by these reporters, Iraqi citizens had to rely on information provided by Saddam’s government, particularly by the Ministry of Information. Heading up this organization was Mohammed Saeed al-Sahhaf. He gave numerous briefings to the many journalists still stationed in Baghdad. These always were upbeat, positive accounts of the war in which Iraqi forces were triumphant. That they were fanciful in the extreme al-Sahhaf seemed not to realize. In fact, the minister was living in a fantasy world. “Yes,” he stated as U.S. forces moved through the Karbala Gap, “the American troops have advanced further. This will only make it easier for us to defeat them.”

The U.S. troops in Iraq nicknamed al-Sahhaf “Baghdad Bob.” To them, he was a source of amusement as he made pronouncements they knew to be untrue. But the minister and his comments also were an irritant. The words he spoke received attention worldwide. They challenged the American account of the war and gave heart to many in the Arab world who wished to see the United States defeated by one of their own.

By April 5, with the marines at the Diyala and the army’s five operating bases secured, the Americans were poised to take control of Baghdad. Generals Franks and McKiernan believed that once the U.S. military controlled the city, Saddam and his regime would be finished. They also believed that the effort to seize Baghdad could lead to protracted urban warfare. This they wanted to avoid. Such combat would be extremely destructive and, more important, would result in numerous casualties, both American and Iraqi.

The two generals knew that the number of troops they had available to assault Baghdad was not large. The capital, after all, was a city of six million people spread out over 440 square miles. How then would the Americans proceed? What was their plan of attack?

They decided to act with caution. There would be no frontal assault, by either the marines or the army troops. Instead, like the British at Basra, the Americans planned a series of raids into the city. These would increase in scale and tempo, gradually wearing down the Iraqis. But before they were to begin, the U.S. Army conducted an operation that became one of the war’s most celebrated episodes.

The operation was called “Thunder Run.” Carried out by a small armored task force, it was a mission of reconnaissance the purpose of which was to ascertain how the Iraqis would fight within the confines of Baghdad. But Thunder Run had more than one purpose. “The task,” said Colonel David Perkins, who commanded the unit to which the task force belonged, “is to enter Baghdad for the purpose of displaying combat power, to destroy enemy forces—and to simply show them that we can.”

U.S. Army doctrine said tanks were not to operate in cities. Urban areas limited their maneuverability, restricted their lines of fire, and exposed tanks to attacks from above. Thunder Run proved the doctrine wrong.

At 6:30 A.M. on April 5, twenty-nine Abrams tanks and several other combat vehicles drove into the city. They traveled up Highway 8, a modern roadway much like an American interstate. What followed, according to Mark Bowden, author of Black Hawk Down, was “the most bitterly contested moment of the war.” It ended two hours and twenty minutes later when the task force, as planned, arrived at the Baghdad airport. One American was dead and one Abrams was destroyed. Estimates of Iraqi losses vary, but at least a thousand men—many of them fedayeen—no longer were alive.

One amusing event occurred during Thunder Run. An Iraqi brigadier general, a staff officer, was driving to work that morning, as he did every workday. Unaware that the Americans were nearby (apparently, he listened to al-Sahhaf’s broadcasts), he turned the corner and promptly drove his Volkswagen Passat into the side of an Abrams M1A1 tank. Needless to say, the car fared poorly and the general, one very surprised Iraqi, became a prisoner of war.

Two days later, a second Thunder Run was conducted. But this was a different kind of mission. The tanks were to drive to the center of the city, a distance of eleven miles, and then remain in Baghdad. The tanks and Bradleys would deploy in a circle, in the middle of the city, and challenge the Iraqis to dislodge them.

Whether the Americans, who reached the city center at 8 A.M. on April 7, would be able to stay in the city depended on the army’s ability to deliver supplies to the task force. This force consisted of 570 soldiers in sixty tanks and other vehicles, and their requirements were substantial. Food, ammunition, and fuel had to be trucked to them. The supply route was up a highway on which three overpasses gave the Iraqis strong positions from which to fire on the convoys. For the U.S. troops, these overpasses had to be taken and held. Given the names Larry, Moe, and Curly, they all saw ferocious firefights. The Americans prevailed, but at times, it was, as the British would say, “a near thing.”

Within the city, firefights took place as well. For two days the Iraqis and the fedayeen tried to kill the Americans, who, having been resupplied, were able to respond in kind. The violence of the combat within Baghdad and at the three intersections, indeed throughout the campaign, can be seen in the following account of one incident as told by David Zucchino in his book about Thunder Run. Captain Stephen Barry was an American officer in Baghdad during the fighting. At one point, his unit sees a white sedan moving directly at it. Barry then gives the order to fire.

Three tanks opened up. . . . The sedan caught fire and crashed. Two men climbed out and both went down, killed instantly. . . . Thirty seconds later, a white Jeep Cherokee sped down the bridge span. . . . 50 caliber rounds shattered the windshield. The Cherokee exploded. The fireball was huge—so big that Barry was certain the vehicle had been loaded with explosives. He knew the difference between a burning car and the detonation of explosives. This was a suicide car.

And they kept coming—sedans, pickups, a Chevy Caprice, three cars in the first ten minutes, six more right after that. The tanks destroyed them all. It was incomprehensible. Barry kept thinking: What the hell is wrong with these people? They were trying to ram cars into tanks. It was futile—absolutely senseless. It was like they wanted to die. . . . Barry hated slaughtering them. And that’s what it was—slaughter.

They were the enemy . . . but it gave Barry no pleasure to kill them.

On April 10, just five days from when U.S. armored units had made their first foray into Baghdad, organized resistance ended. Within the city, the fighting had produced casualties—most of them Iraqi and fedayeen—but McKiernan’s troops now controlled the capital. Saddam had fled and his government had collapsed. Four days later, on April 14, the United States declared major combat operations to have ended.

“Mission Accomplished” read a banner on the USS Abraham Lincoln, one of the aircraft carriers that had participated in Operation Iraqi Freedom. In just twenty-six days the Americans had taken control of Iraq. Little did they expect that the hard part was just beginning.

***

The war against Saddam and his army had been a success. The occupation that followed was not. Throughout Iraq, especially in the cities, American troops first hailed as liberators soon came to be seen as foreigners occupying a country in which they did not belong and governing a people they did not understand.

The immediate problem was one of looting. Once Saddam’s regime collapsed, law and order disappeared. Iraqis responded by breaking into stores and office buildings, and walking off with whatever they could take. U.S. soldiers and marines just looked on, unwilling to stop the thefts. “We did not come to Iraq,” said one American commander, “to shoot some fellow making off with a rug.”

The looting foreshadowed the violence that was to permeate postwar Iraq. Once Saddam’s hold on power ceased, Iraqis chose to seek vengeance on other Iraqis. Shiites killed Sunnis. Sunnis murdered Shiites. Revenge was sweet. Baghdad became a bloody city whose inhabitants were at war with one another. American troops were the only force potentially capable of freeing Iraq from violence. But they were too few in number. Secretary of Defense Rumsfeld had mandated a small military presence in Iraq, expecting the Iraqi army and police force to maintain order once the combat was over. Yet the army had disappeared. Soldiers simply had taken off their uniforms and gone home, while the police were incompetent, capable of little more than traffic control. So as spring turned to summer and summer gave way to fall, Iraq was home to a rampage of killings that the Americans were unable to prevent.

Only in time and when President Bush ordered a surge in the number of troops stationed in Iraq did the violence recede. But for several years following the ouster of Saddam, Iraqis targeted American soldiers and workers. U.S. casualties were many, and constant. Extremists wanted either to destabilize the governing authorities or force the Americans to leave. Not surprisingly, back in the United States, the country’s citizens were angered by what they saw happening in Iraq. Bombs were exploding and people were dying. Opposition to the American presence in Iraq grew as many Americans came to believe that the war had been wrong and the occupation a failure.

As the killing continued—often by suicide bombers—the United States was attempting to rebuild Iraq. Funneling literally billions and billions of dollars into the country, America hoped to create an infrastructure equal to that of any modern country. In this effort the success would be limited.

The difficulties were threefold. The first was the task itself, which was much larger than the U.S. had expected. The second was the corruption that seemed to permeate Iraqi society. The third difficulty, and the most serious, was the lack of security. Workers attempting to rebuild the country’s infrastructure were the target of attack by Iraqis attempting to foil America’s reconstruction efforts.

The result was that the rebuilding of Iraq was less successful, took longer, and cost more than the Americans expected. Iraqis, at least those without blood on their hands, were frustrated. While during the days of Saddam electric power had been limited, those in Baghdad could not now understand why it remained so. How, they asked, could a nation that had landed men on the moon not be able to provide ample electricity to Iraq’s capital?

Despite the violence and the slow pace of rebuilding, the United States did enjoy a few successes in postwar Iraq. Preparations had been made in case food shortages emerged. They did not, but nonetheless, no Iraqi went hungry once American troops controlled the country. Iraqi currency, festooned with images of Saddam, was swiftly and successfully replaced. Much later, in 2005, the United States prodded the Iraqis into drafting a new constitution and holding free and open elections, activities then rarely seen in the Arab world.

At first, the American effort to rebuild Iraq was given to the newly established Office of Reconstruction and Humanitarian Assistance. This was led by Jay Garner, a retired senior American army officer. One of his key staff members, David Nummy, wrote that Garner

struck me as one of those people who had successfully made the transition from warrior to statesman. He was a natural leader and understood the differences between waging war and establishing peace. From my perspective, he had the correct vision for post-invasion Iraq—to get life back to normal as quickly as possible and turn the country back to the Iraqis.

However, with insufficient resources and an environment marred by violence, Garner had no chance of succeeding and did not. He was replaced by Ambassador L. Paul Bremer, who, reporting to Rumsfeld, essentially ruled the country. Bremer inherited an extremely difficult situation, made worse by two of his early decisions. He chose not to immediately reconstitute the Iraqi army, and he forbade most of Saddam’s Baathist Party members from participating in the rebuilding efforts. The former meant security forces were insufficient to keep order, while the latter deprived the effort of individuals capable of carrying it out.

The occupation of Iraq can be said to have ended on August 18, 2010, when, at the direction of President Barack Obama, the last U.S. combat troops left the country. For the United States, the experience had been a painful one. After nearly nine years in Iraq, more than 4,480 American soldiers and marines were dead.

During the time when U.S. soldiers and marines were on patrol in a postwar Iraq, when combat with Iraqi army units had ended, many Americans questioned the wisdom of the war itself, especially as body bags kept arriving at Dover Air Force Base in Delaware. These Americans viewed the conflict as a grave mistake. After all, they pointed out, no nuclear weapons were ever discovered. And Saddam’s alleged possession of such devices had been a primary justification for the invasion.

Others disagreed. They noted that Iraq became, if slowly, a land with a much reduced level of violence. And they pointed out that the country’s leaders had come to power via free and open elections. Regardless of how history judges Operation Iraqi Freedom, there is no doubt that the United States military, spearheaded by American armored forces, performed extremely well. George Patton would have approved.

Did Saddam have any realistic hope of defeating the American and British forces that invaded Iraq?

No, he did not. In equipment, training, tactics, and leadership, the British and Americans outclassed the Iraqis, who, at times, fought courageously, but never in a manner that would result in victory.

Did President Bush rush into war with Iraq?

His critics certainly think so. But Mr. Bush gave Saddam ample opportunity to comply with the United Nations resolutions and thus to avoid armed conflict. Moreover, well before the March 2003 invasion, the American president went to the U.N. and secured a resolution that he and others believed authorized the use of force.

Did Saddam’s government possess nuclear weapons?

American and other intelligence services had told President Bush that a very strong case could be made that Iraq had nuclear weapons. However, postwar searches failed to discover any. To be sure, Iraq had the capability to develop such devices. But, in fact, Saddam did not have these weapons in his military arsenal.

In what other way did the American government miscalculate?

Incredibly, the Department of Defense, having made and executed extensive plans for the defeat of the Iraqi military, made few plans for the administration of Iraq once combat had ended. Secretary Rumsfeld and his colleagues incorrectly assumed that American troops would be able to leave Iraq soon after Saddam’s regime had been ousted. “There is no plan,” said Richard Perle, one of these colleagues, “for an extended occupation in Iraq.” But Secretary of State Colin Powell had warned President Bush that once the United States “broke” Iraq, it would “own” the country. Having done the former, America became responsible for Iraq, at least for maintaining order and for helping to rebuild the country. In the event, both tasks proved difficult and expensive. The U.S. Treasury would send bundles of dollars to Iraq. More importantly, coffins containing the bodies of dead American soldiers would be flown home from Iraq for years after the fall of Saddam.

What happened to Saddam Hussein?

As American armored units entered Baghdad, Saddam went into hiding. Not until December of that year, 2003, was he found, in an underground hole near Tikrit, north of the capital. The Americans who located him interrogated the former ruler and then turned him over to the Iraqis. They brought him to trial and, not surprisingly, found him guilty. On December 30, 2006, they hung Saddam Hussein.