A

Accountant

The demand for accountants soared as new businesses and industries were created in the 19th century. There was nothing to stop women working as accountants, and they are recorded as such in the census (e.g. in 1881 Amelia Barrett, 47 years old, of Islington, or Isabella Brown, 29 years old, of Lambeth). The ‘world’s first professional body of accountants’ – the Institute of Chartered Accountants of Scotland (ICAS) – was awarded its royal charter in 1854; the first professional body in England, the Institute of Accountants in London, was formed in 1870 and in 1880 the Institute of Chartered Accountants in England and Wales (ICAEW) was also established by royal charter. However, there was determined resistance to admitting women as members, which it was thought would ‘lower the status of the profession’.

Mary Harris Smith (1847–1934) was obviously born with a love of figures and had worked as an accountant for some time before her first attempt to gain membership at the age of 41. By 1888 she had her own business in London and that year she applied to join the ICAEW but was refused admission because she was a woman. In 1889 and 1891 she was similarly turned down by the Society of Incorporated Accountants and Auditors (SIAA, formed in 1885, merged with the ICAEW in 1957) – in the 1891 census she is recorded as a ‘practising accountant’. Nearly 20 years later, in 1918, the SIAA changed their rules to allow the admission of women and voted to admit Mary Harris Smith as an Honorary Fellow. Mary, by now aged 72, renewed her application to the ICAEW and in 1919 became the first, and only, female chartered accountant in the world.

Although the professional gates were open, relatively few women followed in Mary Harris Smith’s footsteps (they still formed only 4% of the workforce by 1980).

After 1870 several professional societies were formed: a history and index can be found on the website of the ICAEW, which also has a searchable database of ‘Accountancy Ancestors’ – ‘Who was who in accountancy 1874–1965’ – which includes obituaries and photographs (Library and Information Service, Chartered Accountants’ Hall, PO Box 433, Moorgate Place, London EC2P 2BJ; telephone: 020 7920 8620; www.icaew.co.uk). The Guildhall Library has a useful leaflet guide to the records it holds relating to the ICAEW and the bodies that predated it; or consult Chartered Accountants in England and Wales: A Guide to Historical Records, Wendy Habgood (Manchester University Press, 1994). The website of ICAS is at www.icas.org.uk.

Actress, music hall artiste

In 1802 the Lady’s Magazine had warned: ‘The stage is a dangerous situation for a young woman of a lively temper and personal accomplishments.’ Over a century later, Noel Coward’s advice to Mrs Worthington not to put her daughter on the stage echoed the sentiment – the theatre was no place for a nice girl. Actresses were sought after, admired and envied, but very often they were outside the pale of respectable society and were sometimes considered little better than prostitutes.

The Victorian actress could only learn her trade by practice. Some, like Dame Ellen Terry (1848–1928), were the children of actors and appeared on stage from infancy but, as Charles Booth summarised in the 1880s: ‘The chief methods of obtaining engagements are (1) by advertising, (2) through an agent, (3) applying directly to the management.’ At the time, rates of pay could be anything from £1 10s to £4 or £5 a week, depending on the theatre and the actress’s place in the stage hierarchy: she might just be a ‘walking woman’ with little or nothing to say. Young actresses with promise might get the chance to understudy a part, or sometimes more established actors took pupils for paid tuition. Not until the establishment of the Academy of Dramatic Art in 1904 (the prefix ‘Royal’ was added in 1920) was there a school where the techniques of stage acting could be taught, but the profession remained one where chance could play as large a part as hard graft and experience in the making of a ‘star’.

An actress of the 19th century would have found employment within the ‘stock company system’, where she worked at a particular theatre performing a repertory of plays, which would be repeated in sequence. Subsequently that system gave way to touring companies or ‘long runs’, where the company of actors performed one play either at different locations or for a long period in one theatre.

Violet Cameron (Violet Lydia Thompson, 1862–1919), centre, with Minnie Byron and other members of the cast of The Mascotte at the Royal Comedy Theatre in 1881. She made her fi rst stage appearance at the age of eight and was a popular performer in operettas, plays and music hall, but became notorious for a series of scandalous love affairs.

The ‘stock company’ routine was revived in the early 1900s as ‘repertory theatre’ or ‘rep’ and was a good training ground for young actresses. Wendy Hiller (1912–2003), who became a highly respected stage and film actress, went into rep at Manchester straight from school in the 1920s and, like many others, gained experience of the theatre as an assistant stage manager before working as an understudy and taking walk-on parts; her big break came in the 1930s with the lead in Love on the Dole, taken to London and then to New York. Since the 1910s more opportunities had been opening up for stage actresses in the rapidly expanding film industry, followed by radio and television, and many actresses moved from one medium to another. There were also women who went into management, such as Annie Horniman, who ran a repertory company after she bought the Gaiety Theatre in Manchester, from 1908 to 1917, and was influential in expanding the opportunities for actors in the early 20th century.

It can be difficult to categorise some individuals – were they actresses, dancers, singers, comediennes, or a combination of all four? The other side of the coin to ‘legitimate’ theatre was the music hall, beloved of the working classes. There had for some time been unlicensed ‘free and easies’ – small theatres, often in rooms attached to pubs, that put on short musical plays (burlettas), pantomimes and bills of variety including singers, dancers, speciality acts and comedians, but by the second half of the 19th century music hall was incredibly popular and had moved into the mainstream; there were literally hundreds of halls in London and provincial towns and cities by the 1870s. The last music hall to be purpose-built was the Chiswick Empire, in 1913, a ‘Palace of Variety’.

‘The great difference between an actor in a theatre and a music hall “artiste” is that whereas the first has his part provided for him, the second has to depend upon his own individual efforts and abilities,’ Charles Booth decided. ‘Music hall artistes bring their own company and their own piece and the manager of the hall has nothing to do but mount it in the matter of scenery.’

The stars were household names in their day – women like Vesta Tilley, Marie Lloyd, Bessie Bellwood, Jenny Hill and Nellie Power were some of those whose catch-phrases and songs were common currency. They were larger-than-life characters and they had to be, to make an immediate impression on an audience in a noisy, hot atmosphere where ‘turn’ followed ‘turn’ and the audience was free to move about – and walk out – at any time. But they were only the well-paid tip of the iceberg and the great majority of performers existed on low wages and uncertain contracts, and lived and died in poverty.

Tracing a woman who worked in the theatre is not easy. It was frequently a peripatetic and uncertain life, the use of stage names was very common, and actresses frequently lied about their age! See My Ancestor Worked in the Theatre, Alan Ruston (Society of Genealogists, 2005), for helpful information on research. The Theatre Museum collections, at Covent Garden until August 2007, have been moved to the Victoria and Albert Museum but see their website (www.peopleplayuk.org.uk) for a wealth of information on people from the worlds of theatre, music hall, pantomime, circus, dance etc. The National Archives has a leaflet on Sources for the History of Film, Television and the Performing Arts available there and elsewhere. An article entitled ‘Under the spotlight’ by Nicola Lisle (Ancestors magazine, June 2007) will also be helpful.

There is advice on tracing music hall and variety artistes at www.hissboo.co.uk/musichall_artistes.shtml. The website of the Scottish Music Hall Society (www.freeweb.com/scottishmusichallsociety/informationwanted.htm) has a page where people post queries on past artistes. See also ballet dancer; film, television and radio; ‘principal boy’.

Actuary

Dorothy Beatrice Spiers (née Davis, 1897–1977) was the first qualified woman actuary, a graduate of Newnham College, Cambridge who gained her degree in mathematics in 1918. She worked for the Guardian Insurance Company and studied for the examinations in her spare time, achieving qualification as a Fellow of the Institute of Actuaries in 1923. By 1960, there were still only eleven female fellows of the Institute.

It is a highly skilled, and highly paid, profession requiring advanced and accurate statistical and problem-solving abilities, usually in the world of insurance, pensions forecasts etc. And it required dedication from women like Dorothy, who refused initial offers of marriage from her future husband because she would not be deflected from her ambition. The first woman to try to break into the profession had been an American, Alice Hussey, in 1895, but the Institute sheltered behind its constitution until the First World War, when the increasing numbers of women filling posts in insurance offices began to bring pressure for change.

The Institute of Actuaries (Oxford, OX1 2AW) has responsibility for England and Wales, while the Faculty of Actuaries (Edinburgh, EH1 3PP) acts in Scotland (the website www.actuaries.org.uk is for both of them). The Worshipful Company of Actuaries was granted its charter in 1979.

Aerated water bottler

Carbonated drinks (using carbon dioxide dissolved under pressure) had been available since the end of the 18th century and were in growing demand throughout the Victorian period; fizzy soft drinks and water were popular in particular with the Temperance movement as alternatives to alcohol. Manufacturers can be found all over the country – Hull, for instance, had over 20 factories producing ginger beer, lemonade, etc by the 1890s. Women were employed in the bottling plants and this could be hazardous work.

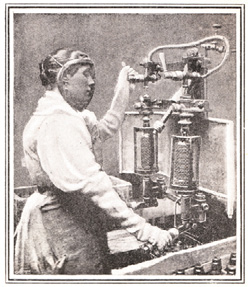

A wire mask and woollen gauntlets protect a woman fi lling bottles with aerated water. (Harmsworth Magazine, 1900)

In 1900 the Harmsworth Magazine published an article by W.J. Wintle that appeared under the skull-festooned title of ‘Daring Death to Live: The most dangerous trades in the world’. It included the women who filled glass bottles with aerated water or soft drinks for R. White & Sons at their Camberwell factory. To protect the women from flying glass, ‘All the bottlers, wirers, and labellers wear masks of strong wire gauze, while their arms are protected with full length gauntlets, so constructed as to cover the palm of the hand and the space between the thumb and fourth finger. It has been found by experience that a knitted woollen gauntlet of thick texture answers much better than one of leather or india-rubber. The bottling machines are so arranged that the bottle is contained in a very strong wire cage during the process of filling.’ The most dangerous point, however, was when the newly-filled bottle was taken out of the machine by hand.

Aeronaut

Name for a Victorian balloonist, or sometimes a trapeze artist in the circus (see circus performer).

Agricultural labourer

Agriculture was historically a major employer of female labour, before domestic service and factory work became more important in the 19th century. By the 1880s there was a feeling in many rural areas that working in the fields (‘goin’ a-field’) was not suitable work for women, although they continued to play an important part in the farming year throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries.

This is one of those occupations where female involvement could vary quite considerably depending on the part of the country; there was always more work for women in arable counties, for instance. In rural areas where women could find other work (such as straw plaiting, lacemaking, glovemaking etc), they tended not to work in the fields, but, if the male labourers’ wages were low and there was no other way for the women to supplement them, they would do so. In Hertfordshire, for example, where straw plaiting provided a good income for women (see straw plaiter), there was very little farm work done by them except at haytime and harvest.

In the early spring they might go out stonepicking – removing large stones from the fields by hand, usually on new acreage or before ploughing – and then follow the plough, gathering up roots and invasive weeds such as couchgrass before the new crops were sown: ‘The cold clods of earth numb the fingers as they search for the roots and weeds. The damp clay chills the feet through thick-nailed boots, and the back grows stiff with stooping’ (wrote Richard Jefferies in ‘Women in the field’, Graphic, 1875). As the crops grew, women would be employed to hoe between the young plants to keep weeds down, and then to pull turnips, swedes, potatoes, etc., or pick fruit and vegetables such as strawberries or peas. In the 1930s, in Lincolnshire, women were employed by the day or by the amount of crops gathered – if it rained the work was muddy and wet: ‘The women were kitted out with wellingtons and trousers and had hessian sacks tied round their middle with binder twine.’

Women working on the land at the beginning of the 20th century, clearing the fields for the plough.

In some areas women helped with the sheepshearing: ‘They handle the wool, cut away and throw out the dirty and knotty parts, and then roll up the fleece, the cut side outwards, ending with the neck, which serves to bind the parcel round. After all the washing and squeezing and paring away, it is a dirty business at best, as any one will say who has unfolded a fleece in the mill.’ (Once a Week, 1860)

If at no other times, country women would usually be out at haymaking and harvest. In June when the hay was ready it had to be cut, then spread out over the ground to dry (‘tedding’) and turned several times. It was then raked up and gathered into ricks in the farmyard for winter feed. This was one area where haymaking machinery gradually superseded some of the traditionally female tasks.

At harvest time, usually in August, women would be out in the fields in the early morning, often with children in tow, to work all day following the reapers to gather the crop. This is generally represented as an enjoyable country romp, but the reality was hard, back-breaking work. Richard Jefferies described the scene: ‘Through the blazing heat of the long summer day, till night, and sometimes under the pale light of the harvest-moon this labour continues. Its effects are visible in the thin frame, the bony wrist, the skinny arm showing the sinews, the rounded shoulders and the stoop, the wrinkles and lines upon the sunburnt faces. Many women labour thus while still suckling their infants; and at night carry home heavy bundles of gleanings upon their heads.’

During the winter months, female part-time labour would not generally be wanted by the farmer. When a woman’s full-time occupation was as an agricultural labourer, however, even during these slow months, she would be employed about the farm. In 1882 Theresa Brown, just 22 years old and soon to be married, died at her home in Watlington, Buckinghamshire, following an accident. She had been recorded in the 1881 census as an ‘ag lab’, ‘working at field work’, and in November 1882 her hand was crushed in the oilcake crushing mill at the Model House Farm, Shirburn; despite amputation of the hand and wrist, lockjaw set in and she died a few days later, ‘after great suffering’.

Because of the seasonal nature of so much female agricultural work it is rarely documented. Village histories may be useful for discovering the local rhythms of life, as may local museums. Labouring Life in the Victorian Countryside, Pamela Horn (Alan Sutton, 1995) is helpful for the background. The Museum of English Rural Life at Reading has a great deal of information about country matters in general; its website has online catalogues, a bibliographical database etc (the museum is at the University of Reading, Redlands Road, Reading RGI 5EX; telephone: 0118 378 8660; www.ruralhistory.org). Read My Ancestor Was an Agricultural Labourer, Ian Waller (Society of Genealogists, 2007) for advice and sources. See also bondager; farm servant; gangworker.

Air Transport Auxiliary (ATA)

The ATA was the brainchild of Gerard d’Erlanger, director of British Airways in the 1930s, when, with war looming, he convinced the government that there would be a need for experienced pilots – who would not be eligible for the RAF by reason of age or perhaps disability – to run an air taxi/despatch service. The ATA remained a civilian air service throughout the war, although it was gradually taken over from BA by the Ministry of Aircraft Production, and was disbanded at the end of the war.

The first intake of male pilots were in place by September 1939. By the time women were recruited for the ATA at the beginning of 1940, ferrying aircraft from factory to aerodrome had become the main task and a desperately important one as the Battle of Britain was fought. Women were not initially welcomed, and it was largely the lobbying of Pauline Gower that swayed the Air Ministry. Miss Gower herself had over 2,000 flying hours under her belt and was a commissioner in the Civil Air Guard; she was made commander of the female ATA intake and became a highly respected officer for the duration of the war.

On 1 January 1940 the ‘First Eight’ officially began duties at the de Havilland works at Hatfield, ferrying Tiger Moths – Winifred Crossley, Margaret Cunnison, Margaret Fairweather, Mona Friedlander, Joan Hughes, Gabrielle Patterson, Rosemary Rees and Marion Wilberforce. All were experienced flyers. By 1942 there were 14 ferry pools in the ATA, and 22 by 1945 – Cosford, Hamble and Hatfield were all-female, while personnel were mixed elsewhere.

At first the women were restricted to non-operational planes, but the drain on personnel was such that by the summer of 1941 they were cleared to fly Hurricanes and Spitfires. Eventually all types of aircraft were included in their rosters, even the heavy four-engined bombers and, by the end of the war, the Meteor jet. In the summer of 1943 they were granted equal pay with their male counterparts, and in late 1944 were cleared to fly to the Continent. The intakes included foreign volunteers, including many from the USA.

The ATA also had female ground staff – some 900 out of a workforce of 2,000 – who worked in offices and training schools, as well as on maintenance of aircraft and armaments.

The uniform was dark blue, with a blue forage cap; brass buttons inscribed ‘ATA’; and insignia of gold wings with ‘ATA’ in the centre. The pilots flew with no radios, no navigational instruments and no armaments, risking attack by enemy fighters as well as our own anti-aircraft batteries. The risks were well illustrated by the loss of one of the world’s leading female pilots, Amy Mollison, née Johnson, in 1941. She is thought to have lost her bearings in bad weather over the Thames Estuary and was drowned when her plane went down. Though these women were non-combatants, they faced death every time they took off. Twenty women died in the service.

Personnel files for the ATA are held by the RAF Museum at Hendon (www.rafmuseum.org.uk), but are only available to the women themselves or their next of kin. Background information can be found on the internet: there is a history of the service at www.airtransportaux.org, which is dedicated to the American women pilots but covers the English side as well; a history and list of ‘incidents and casualties’ at www.fleetairarmarchive.net; a range of photographs at www.bamuseum.com; and a history and photographs at www.raf.mod.uk/history. The National Archives has some records for the organisational side of the service. The ATA Association can be contacted via Wing Commander Eric Viles, 40 Goldcrest Road, Chipping Sodbury, Bristol BS17 6XG.

There have been several books about, and by, the women who flew, including Brief Glory, the official ATA history published in 1946, and the most recent, The Spitfire Women of World War II, by Giles Whittell (Harper Press, 2007). All the websites given above have good booklists for further reading.

Almeric Paget Military Massage Corps

Founded by Mr and Mrs Almeric Paget in 1914 (and originally called just the Almeric Paget Massage Corps), the APMMC provided over 100 trained masseuses to military hospitals in this country during the First World War and also supported an out-patients department in London. The success of these early physiotherapists in treating wounded servicemen was so great that the Corps was recognised by the War Office as the official body for the employment of masseurs and masseuses for military hospitals for the duration of the war, and in 1916 the word ‘Military’ was added to the title (in 1919 abbreviated to the Military Massage Service). Corps members served both in the UK and overseas (from 1917) – by 1919 there were some 2,000 in the service.

See www.familyrecords.gov.uk/focuson/womeninuniform/almeric_profile.htm for more details, and a profile of the service of Ethel Jones, a nursing sister in the Corps; for general information see the Women’s Work Collection of the Imperial War Museum; and pension records may be available at The National Archives. The names of members of the Corps may be found in the contemporary issues of the journal of the Society of Trained Masseuses. See physiotherapist.

Almoner, lady

The office of almoner is an ancient one, deriving from the Christian tradition of the Church and King distributing charity to the poor, but it is the ‘lady almoner’ we are concerned with here. It was a post that was ‘female’ from its inception. In 1895 Mary Stewart was appointed as almoner at the Royal Free Hospital in London, the first of her kind and something of an experiment, paid for by the Charity Organisation Society (COS – today the Family Welfare Association – which since the 1870s had been using ‘assessors’ in a similar role).

Large hospitals such as the Royal Free were facing the problem of being too popular for their own good – out-patient departments were becoming grossly overcrowded by people who could be equally well treated at a dispensary or at home, while the perennial task of separating those who could and should pay for their treatment from those who were entitled to free treatment was not being addressed. The almoner made sure that better-off patients paid the cost of their treatment, and that poorer patients could continue their treatment or convalescence when they left the hospital. She could offer financial assistance to those who needed it, arrange care for children, advise on cleanliness, cooking and nursing in the home, and any social problems, find work for those who lost their jobs because of illness, arrange apprenticeships for young men and women, liaise with the NSPCC in cases of child cruelty, and so on – it comes as no surprise to know that her job was eventually superseded by that of the social worker.

They were few in number, each hospital making its own decision as to whether it was financially worthwhile, and when the Hospital Almoners’ Association was formed in 1903 it had only 13 members. Demand by hospitals continued to increase during and after the First World War, and in 1920 it was given to the Hospital Almoners’ Association to organise the profession and the Institute of Hospital Almoners to set the examinations. In 1945 the two were combined into the Institute of Almoners (which became the Institute of Medical Social Workers in 1964). After 1948 and the coming of the National Health Service, the financial aspect of their work ceased but the almoner’s department was still to be found in hospitals for some years, dealing now with social problems, discharge of patients, etc.

As hospital employees, records of almoners, where they still exist, will be found with hospital archives. Some charities also employed almoners, for the same kind of work as those in hospitals – in effect, assessing whether applicants were eligible for help, visiting, and advising on the best use of resources. The records of the Institute of Medical Social Workers 1895 to 1971 are held at the University of Warwick, Modern Records Centre – see their subject guide ‘History of Social Work’ for sources (www2.warwick.ac.uk/services/library/mrc).

Apothecary

When Elizabeth Garrett was beginning her attempt to storm the medical establishment in the 1860s, she gained the diploma of the Society of Apothecaries in 1865 as a way of getting her name onto the Medical Register. The Society had been granted its charter in 1617; the word apothecary was derived from the Latin apotheca, a place where wine, spices and herbs were stored, and reflected the profession’s origins as those who made up and sold drugs and gave medical advice, like today’s community pharmacists. In 1704 a long-running battle with the Royal College of Physicians was settled in court with the agreement that apothecaries be allowed to prescribe and dispense medicines. A century later, in 1815, the Society became responsible for regulation by licence of all those allowed ‘to practise medicine’, restricting membership to those who gained the Licentiateship (LSA; from 1907 the Licence in Medicine and Surgery, LMSSA) by an apprenticeship of five years, or, from the 1850s, attending lectures and examination. Some apothecaries also qualified as surgeons, and the origins of our general practitioners lie with this profession.

However, for hopeful women doctors in the 1860s, the interest primarily lay in the fact that the Society’s examinations were open to ‘all persons’ and, under threat of legal action by Elizabeth Garrett’s father, they were forced to admit that this included any woman who had fulfilled the same conditions as a man. Gaining the qualification enabled her to open a dispensary for women in London and take the first step to full registration as a doctor. The Society hurriedly bolted the stable door by changing their rules to exclude women, which was the situation until after the First World War.

The Society of Apothecaries has been involved in much of the development of the medical profession: see doctor; midwife; pharmacist. The Society’s website (www.apothecaries.org) has details of its archives, but many have been microfilmed and are freely available at the Guildhall Library.

Archaeologist

Women were active in archaeology from the late 1800s, quickly taking advantage of the new opportunities to obtain a higher education once they were allowed into universities, despite the difficulties put in their way by the male academic hierarchy – as late as 1939, when the highly respected archaeologist Dorothy Garrod (1892–1968) was elected to the Disney Chair at Cambridge University, women were not accepted as full members of the university or allowed to attend public awards ceremonies, and still got their certificates by post; it would not be until 1948 that they were allowed to officially graduate (see the Newnham College website, www.newn.cam.ac.uk, for biographical details of their distinguished female alumni).

Sometimes archaeology, travel and adventure seem to have formed a potent mix for women. Gertrude Bell (1868–1926) led a colourful life after graduating from Lady Margaret Hall, Oxford (the first woman to get a First in Modern History at Oxford), spending a considerable time in Iraq and founding the National Museum in Baghdad after the First World War; her remarkable times are described in Desert Queen: The Extraordinary Life of Gertrude Bell by Janet Wallach (see also http://wingsworldquest.org). Katherine Routledge was another pioneer, one of the first female graduates from Oxford and the first woman archaeologist to work in Polynesia. She led the Mana Expedition to Easter Island 1913–1915 and performed the first excavations of the famous stone figures: see Among Stone Giants: The Life of Katherine Routledge and her Remarkable Expedition to Easter Island, Jo Anne Van Tilburg (Scribner, 2003). Few in number, the women who followed this profession made their mark, such as Margaret Taylor (1881–1963), who was elected a Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries in 1925 and was secretary of the Society for the Promotion of Roman Studies from 1923 to 1954 and president in 1955.

Architect

The designing and construction, or restoration, of buildings has always been a prestigious occupation, and today the use of the word ‘architect’ is protected by law and can only be assumed by those who have followed the course of training recognised by the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) and the Architects Registration Board. By the 1920s associateship or fellowship was open to both men and women, although as usual the profession had put up a strong resistance to the entry of female candidates.

Ethel Mary Charles is believed to have been the first qualified woman architect in England (though others may have been working in the field before that, as with accountants). Following a period under articles with the firms of Sir Ernest George & Peto and Mr Walter Cave, she sat her final examinations in 1898 and was elected an Associate Member of RIBA in that December. She had a particular interest in Gothic and domestic architecture, and was registered as practising in York Street Chamber, London.

By the 1920s there were several female architect partnerships, such as that of Norah Aiton and Betty Scott in Derby, and in 1928 Elisabeth Whitworth Scott won the competition for a design for the new Shakespeare Memorial Theatre at Stratford-upon-Avon, a prestigious award that brought the work of women architects into the public eye. In the 1930s the proportion of women among the students at the School of Architecture of the Architectural Association was one in five, but during the Second World War it increased to about one in two. ‘By now it is generally recognised that women are well fitted for this important and exacting profession, and on completing their training they are employed, whether by Government departments or local authorities, or in private practice, on the same terms as their male colleagues,’ said The Times in September 1943. Women were thought to have something extra to contribute to the planning and reconstruction of a post-war world; during the war the usual five year course of study was compressed into three and a half years so that young women could get at least as far as their intermediate examinations before they became eligible for call-up at the age of 20.

The website of the Royal Institute of British Architects, London W1N 6AD (www.architecture.com) has a biographical database of architects and a searchable catalogue; their library is open to the public by appointment. A ‘Dictionary of Scottish Architects 1840–1940’ can be found at www.codexgeo.co.uk/dsa/, which includes pioneers such as Edith Burnet Hughes (1888–1971), who had her own practice in Glasgow in the 1920s but was refused admittance to RIBA. The book Women and Planning: Creating Gendered Realities, Clara Greed (Routledge, 1994) names many women working in architecture, planning and surveying in the 19th and early 20th centuries.

Artificial flower maker

A glance at any fashion plate of the 19th and early 20th centuries, when hats and dresses were enhanced with elaborate adornments, makes it clear why the art of artificial flower making employed hundreds of girls and women.

The best quality artificial flowers – intended for the most fashionable creations – were prepared in small factories, but it was also work done at home. In 1896 in Home Life a wholesale dealer explained that the Franco-Prussian War of 1870 had boosted the British industry because previously the majority of artificial flowers had come from France or Germany. ‘Cutters who cut the leaves, petals, etc, with a stamp cutter start at 7s a week, gradually rising to 14s; there is very little skill required, so the wages are not very high. Shaders, viz, those who dip the various parts in the dye, shade and strip them, earn better money, theirs rising to 25s. From these we come to the leaf makers; here we require skill, and a girl who is sharp and has good taste will take an average of £1 per week, whilst during the busy season, by working overtime, as much as 35s is earned.’ Skilled workers in the ‘mounting and making’ departments earned 35s to £2 a week. The work was not without its dangers – the dyes used for colouring contained arsenic.

The flowers were made of materials such as silk, cotton, taffeta or organdy, and it was a job that required nimble fingers, the smaller pieces having to be manoeuvred using tweezers. Petals, blossoms, buds, leaves and stalks all had to be cut out, the petals and leaves curved and shaped to match Nature. The whole creation was wired and glued together, dyes were used to colour the materials, and feathers and other decorative features added – including artificial fruit and small stuffed birds! Flowers were also used for wreaths and bouquets, cake decoration and home furnishings.

At the bottom end of the market were the coloured paper flowers made for the poor by the poor. Women who made paper flowers in the winter may have been engaged in making and hawking fire-stove ornaments in summer – these were made of coloured paper and tinsel, with streamers and rosettes, and were bought by the working class to ornament their hearth in summer when the stove fire was out.

Artist

‘Never has the position of woman in the field of English art been so strong as it is today,’ wrote Arthur Fish in the Harmsworth Magazine in 1900. ‘There, as in other branches of work, she is competing closely with men; in some instances equalling him; in a few, outdistancing him . . .’. Yet, he mused, ‘It is curious that in spite of the fact that women students carry off a large percentage of the prizes from the Academy Schools each year, and that women artists contribute largely to the success of the annual exhibitions at Burlington House, the members [of the Royal Academy (RA)] continue to fail to recognise the right of women to be represented in the Academy itself.’ Without that recognition from the RA, women could not be regarded as truly professional artists. Despite the fact that the Academy had been started in 1768 with the backing of two female artists, Angelica Kauffmann and Mary Moser, no woman had ever been elected to membership.

The woman whose career Mr Fish chose to illustrate his point was Elizabeth Thompson (1846–1933), who when she married Sir William Butler became Lady Butler and who was recognised as one of the finest painters of battle scenes of the 19th century. She had a phenomenal public success with her paintings The Roll Call in 1874 and The 28th Regiment at Quatre Bras in 1875, but her four attempts to be accepted as a member by the RA failed. The fourth, and last, time was in 1879, when she was beaten in the voting, by two votes, in favour of Hubert von Herkomer. See Lady Butler, Battle Artist 1846–1933, Paul Usherwood and Jenny Spencer-Smith (Alan Sutton, 1987), for more on this remarkable artist. Only in 1922 was a woman accepted as an Associate Member (Annie Swynnerton), and the first female Academician was Laura Knight in 1936. This sidelining of even the best of female artists is perhaps the reason why for so long there was a common belief that there were ‘no women painters’ in the Victorian period.

For girls interested in serious training as an artist, there were a number of well-known schools by the early 1900s, most of them with a majority of female students. The famous Newlyn School in Cornwall, for instance, took about 30 students at a time, of whom two-thirds would usually be women – Mrs Stanhope Forbes took a personal interest in them and made sure that their lodgings in cottages in the village had her approval – while the Bushey School of Animal and Figure Painting was by 1910 under the direction of the artist Lucy Kemp-Welch. Schools of art were also opened by colleges and universities all over the country, offering examination courses for those who wanted to go on to teach. Some women set up on their own account and offered tuition in drawing or painting in their own homes. There was also work in illustrating books, newspapers and magazines – see illustrator.

An internet gateway to art libraries and archives is provided by Goldsmiths College at http://libweb.gold.ac.uk/subgates/artlibgate.php, while the website of the National Art Library at the Victoria and Albert Museum has a page on ‘Finding information about artists’ with a bibliography and links (www.vam.ac.uk/nal/findinginfo/info_artists/index.html). There are several books with short biographical entries for artists, such as the Dictionary of Victorian Painters by Christopher Wood (Antique Collectors Club, 1971). For a general background see Women Artists in 19th Century France and England, Charlotte Yeldham (Taylor & Francis, 1984).

Auctioneer

The auctioneer organises the salerooms, assesses items for sale, and controls the auction itself. In a specialist auction house it is a job that requires experience and expertise in fine arts, and, in general, confidence and quick wits are essential.

A shortage of men in the London auction rooms during the First World War gave Evelyn Barlow the chance to conduct sales at Sotheby’s in July 1917. She was the sister of Sir Montague Barlow, MP, senior partner of Sotherby, Wilkinson & Hodge, and her ‘career’ seems to have been brief. In 1940, a similar situation brought Mrs Helen Naddick to the rostrum at Bonham’s, the family business (she too was a sister – of Leonard Bonham, who had been called up) but in her case it did indeed lead to several years in auctioneering. In 1956 she was asked if a girl could make a career in the salerooms and replied that opportunities were limited but she saw no objection. It was not until 20 years later, however, that Sotheby’s and Phillips’ both appointed young women as career auctioneers.

Outside the big specialist salerooms there were women acting as auctioneers, though often because of the absence of men in wartime – a woman was conducting the weekly cattle sales at Mansfield in 1917; an ‘exceptionally successful’ woman was employed in 1919 by Messrs Harmer, Rooke & Co, stamp dealers of Fleet Street; and a woman who carried on after the death of her husband had a successful business in Wandsworth Road in the early 1920s. They were enough of a rarity to be reported in local newspapers. Women also worked in salerooms in other capacities, such as clerk or secretary (in 1891, for example, Eleanor Smith, 36 years old and living in the St George’s Hanover Square area, was working as a ‘Secretary to Exchange & Sale Room’). There are also close connections between auctioneers and estate agents; in fact, working as a clerk for three years or more was one way by the 1930s to enter the profession, allowing entrance to the examinations of the Auctioneers’ and Estate Agents’ Institute of the United Kingdom. Otherwise, it was by serving three years (usually) in articles with a practising auctioneer, and paying a premium, from 100 guineas to 500 guineas.

Auxiliary Territorial Service (ATS)

The ATS was formed in September 1938 under Dame Helen Gwynne-Vaughan. Initially the Service worked with the Army and the RAF, but their duties revolved solely around the Army after the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force was formed in 1939. Their uniform was army khaki – ‘not a becoming colour’.

By the time war was declared in September 1939 the ATS was in action – in fact, the declaration of war was transmitted by an ATS wireless operator. In the spring of 1940 part of the Women’s Transport Service (FANY) – see First Aid Nursing Yeomanry – was incorporated into the Service (members were allowed to keep their ‘FANY’ shoulder flashes). In April 1941 the ATS was brought under the Army Act, meaning that its members were accepted as part of the Armed Forces, although they were assured by the Secretary of State that ‘the Service will remain a women’s service under the general direction of women’. The women received two-thirds of the pay of a man of the equivalent rank.

Although volunteers were sufficient to man the Service at first, by 1942 conscription had become necessary to replace men needed for active service. The ATS filled a wide range of duties for the Army. At first they were accepted only as cooks, clerks, orderlies, storeswomen and drivers, but by December 1943 there were over a thousand categories of employment open to them. The ATS numbered some 212,000 women at its height. They filled 80 trades, including armourers, draughtswomen, fitters, welders and wireless operators, as well as fulfilling the usual clerical, catering, driving and orderly work. They could be found attached to the Royal Army Ordnance Corps, the Royal Corps of Signals, and the Royal Army Pay Corps. Some with engineering qualifications worked with the Royal Electrical and Mechanical Engineers. Much of the Army Blood Transfusion Service was run by the ATS, including the ‘bleeding teams’, that went round the country collecting blood.

After 1941 they also served in mixed ack-ack batteries with the Anti-Aircraft Command – the first ATS Searchlight Troop was formed in July 1942. They did not man the guns (well, not officially, anyway) but worked alongside the Royal Artillery as instrument operators, plotters and radiolocation operators. At the end of 1944 mixed batteries were sent to France for the first time. The Girls Behind the Guns: With the ATS in World War II, Dorothy Brewer Kerr (Robert Hale, 1990) describes life in the batteries by a woman who was there.

Any ATS auxiliary aged between 19 and 40 was liable for service overseas and the first girls had been posted to France in the spring of 1940 with the British Expeditionary Force – just in time for the Fall of France. They were evacuated with the Army, but stayed manning vital switchboards to the last possible moment as the Germans entered Paris. Junior Commander Mary Carter was awarded the MBE for her part in bringing out 24 ATS girls, plus one female French liaison officer they smuggled out in a spare ATS uniform. Wherever the Army went, the ATS went too. Hundreds were sent out to the Middle East, for instance, providing support during the North Africa Campaign and earning themselves the Africa Star medal. Sgt Janet Fitzgerald was one of four girls sent to the West Indies to recruit local girls for an ATS unit to be based out there to work with British troops.

The ATS became a regular Army corps on 1 February 1949, and was renamed the Women’s Royal Army Corps (WRAC) – it was disbanded in 1992.

ATS personnel records are held by the Ministry of Defence and will only be released to the women themselves or proven next of kin, for a fee: Army Personnel Centre, Historical Disclosures, Mailpoint 400, Kentigern House, 65 Brown Street, Glasgow G2 8EX (telephone: 0141 224 3030; e-mail: apc_historical_disclosures@dial.pipex.com).

There is some background information at www.atsremembered.pwp.blueyonder.co.uk, and the Imperial War Museum has an information sheet on ‘The Auxiliary Territorial Service in the Second World War’, which gives guidance on research sources. The contents of the WRAC Museum at Guildford, which closed in the 1990s, are now at the National Army Museum (Royal Hospital Road, Chelsea, London SW3 4HT; www.national-army-museum.ac.uk). See also The Women’s Royal Army Corps, Shelford Bidwell (Leo Cooper, 1977).

New recruits to the ATS, attached to the Beds and Herts Regiment, at Folkestone in 1939. The only named member is Hilda Suckling, second right in the middle row. (Maureen Jones)