D

Daily maid, daily

By the 1920s, with living space at a premium for many people in smaller houses and flats, employing a daily house-parlourmaid or cook for a set number of hours each day was often the only way they could manage to have a servant. (If all they wanted was cleaning, see charlady, charwoman.) ‘Frequently she is a woman of a competent and superior type, the wife, perhaps, of a disabled soldier, obliged to return to service in this form, highly recommended by the better-class registry which supplies her.’ (Good Housekeeping magazine, 1923.)

Dairymaid

A good dairymaid could be worth her weight in gold to a dairy farmer producing butter and cheese for sale. While a hill farm, or any small farm, might make butter or cheese for family consumption only in the summer when the milk was at its best, a dairy farm would be in production all year round for market.

On many farms the dairying was done by the farmer’s wife, who would in any case probably oversee the work in the dairy, but often on larger farms a woman with specific responsibilities was employed. By the mid-19th century, the dairymaid was also making an appearance in middle-class suburban villa establishments, where the mistress of the house might have a fancy to keep a cow or two and some poultry, in which case the maid would combine her duties in the dairy with other household service.

In the 20th century, when it was feared that the old skills were being lost, dairy schools (recognised by the Board of Education) were set up to bolster the industry and teach a new generation how to make good butter and cheese – the one in Gloucester in the 1930s was run by a Miss Collet. The dairy teachers were employed by the local county council.

On some farms the dairymaid would also help with the milking of the cows (see milkmaid), but usually any connection between the cowshed and the dairy was kept to a minimum. Cleanliness was absolutely vital and much of a dairymaid’s time was spent in washing and scouring clean her equipment and utensils. It was in the churning and kneading, for butter, that a dairymaid’s skill was tested, and likewise in the cutting up of the milk curds and the pressing and storing of cheeses.

For an idea of the kind of equipment used in the dairy, see Dairying Bygones, Arthur Ingram (Shire Publications, 2002), or pictures on the website www.fellpony.f9.co.uk (Dales farming). Many county or agricultural shows had competitions for dairying, and reports may appear in local newspapers.

Deaconess

To become a deaconess (an ‘accredited lay worker’) was the only way in which a woman could train theologically and minister to a community in the Anglican church in the 19th century – she was a single woman, ‘set apart’ but, unlike a male deacon, not ordained. The role was formally recognised in 1891 but it would be 1987 before women were admitted to the order of deacon (and 1994 before they were admited to the priesthood).

The deaconess movement was a significant factor in the second half of the 19th century, coming at a time when women were creating a new image of themselves as an independent sisterhood in nursing, education and what we now call social work. In 1862 Elizabeth Catherine Ferard received her licence from Bishop Tait of London, the first woman to do so. She founded a community of deaconesses, which was also a religious sisterhood – the (Deaconess) Community of St Andrew, working originally in a poor parish in the King’s Cross area of London and at the Great Northern Hospital; St Andrew’s House is now the world headquarters of the Anglican Communion. Isabella Gilmore was another influential figure, licensed in 1887; see Isabella Gilmore, Sister to William Morris, Janet Grierson (SPCK, 1962). There is more information on women and the Anglican Church at www.watchwomen.com. See also minister of religion.

Dentist

In the mid-19th century the dentistry profession was completely unregulated and there was no way of knowing if a person was competent or not – surgeons might carry out dentistry as a speciality, but others who practised included chemists and even watch-repairers (because they were craftsmen who could produce false teeth and dental aids), and training was by apprenticeship rather than approved courses of study and examination.

From 1860 the Licentiate in Dental Surgery (LDS) was granted by the Royal College of Surgeons (and names of dentists appear on the Medical Directory after 1866). In 1878 the British Dentists Act laid down that only those who had gained recognised training could call themselves a ‘dentist’ or ‘dental surgeon’ and be included on a new Dentists’ Register – but, as there was no actual legal requirement to register, control of the profession remained elusive.

Dental schools existed from the 1850s, for instance at Birmingham Dental Hospital and under the Royal College of Surgeons at Edinburgh. They were slow to accept female students and the first woman to qualify as a dentist in Britain was Lilian Lindsay (1871–1960) in 1895; she graduated in dentistry at the Edinburgh Dental School and had a distinguished career, becoming president of the British Dental Association in 1946. There were, however, women practising as dentists before that – Dr Harriet Boswell, for instance, at 25 Queen Anne Street, London, in the early 1890s.

There were also women who had a less professional approach. In A Wanderer in London, E.V. Lucas wrote in 1911 of being ‘fascinated by the despatch, the cleverness, and the want of principle of a woman who sold patent medicines from a wagonette, and pulled out teeth for nothing by way of an advertisement. Tooth after tooth she snatched from the bleeding jaws of the Commercial Road, beneath a naphtha lamp, talking the while with that high-pitched assurance which belongs to women who have a genius for business, and selling pain-killers and pills by the score between the extractions.’

The Dentists’ Register has been maintained since 1879, with name, address and qualification. It was not until 1921 that all practising dentists had to be on the register, and to have a qualification from a recognised dental school.

The British Dental Association was founded in 1880 and the museum has information on how to trace dentist ancestors; photographs and archives: the museum is at 64 Wimpole Street, London W1G 8YS (www.bda.org/museum). There is an online history of professional dentistry at the website of the Faculty of Dental Surgery, Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh (www.rcsed.ac.uk/site/682/default.aspx). Not particularly about women dentists but great fun is The Strange Story of False Teeth, John Woodforde (Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1983) – although it does mention Helen Mayo, whose evidence about a victim’s teeth in 1949 helped to convict John Haigh of the Acid Bath Murder.

Dinner lady

A much maligned woman, blamed for memories of soggy cabbage, gristly meat pies and lumpy custard, the ‘dinner lady’ arrived with the first school meal; she prepared, cooked and served the food in the school dining room.

From the 1860s voluntary groups in cities such as Manchester, Newcastle upon Tyne, Birmingham and London began to provide hot dinners for poor children, but it was once compulsory education was begun in the 1870s, when it became all too clear that thousands of children were so ill-fed as to be on the edge of starvation, that some school boards also became involved. The poor diet of the working class was a particular cause for concern when Army recruitment for the South African War in 1899 revealed an underclass of ill-nourished workers, stunted in growth.

In 1906 the Education (Provision of Meals) Act gave local authorities the powers to provide hot meals in elementary schools, paid for by parents or the imposition of a local rate. Uptake was patchy throughout the inter-war years, with some authorities more generous than others; in Bradford ‘children could have porridge, bread and treacle and milk for breakfast and a variety of cooked dishes for dinner, including onion soup, hashed beef, shepherd’s pie, fish and potato pie, baked jam roll and rice pudding,’ according to John Burnett (‘Eat your greens’, History Today, March 2006). However, school meals for all became a statutory provision under the 1944 Education Act.

Dinner ladies and school cooks were the employees of the School Meals Service of the local education authority and any staff records that may survive will be found usually in county archives.

Dispenser, dispensing assistant

Training as a hospital dispenser took a three-year apprenticeship under a qualified chemist, but when, in the days before the National Health Service, GPs often had their own dispensaries on site in their practices and made up medicines and pills on the spot, they might accept someone with the less advanced Apothecaries’ Assistant qualification.

The dispensing assistant, frequently a woman, was also part receptionist, part first-aider, part book-keeper and general all-round assistant. There is a description of one woman’s experiences in the 1940s in Hampshire Within Living Memory, Hampshire Federation of WIs (Countryside Books, 1994): ‘One was expected to test urine and blood samples for a diversity of medical conditions; deal with accidents and emergencies when the doctors were out of the surgery; sterilise instruments and assist at minor operations. Book-keeping, filing, wages and general clerical work, not to mention typing, were all part of the job. Additionally it helped if one could unblock drains, smooth ruffled feathers and make a good cup of tea.’ See pharmacist.

Doctor, surgeon

The arguments against accepting women as medical students and then as qualified medical practitioners seem now fairly illogical – they were too emotional; their brains were smaller than a man’s; they could not take the rowdy atmosphere of the dissecting room or the operating room (and the male medical students were indeed rowdy); they could not be alone with a male patient etc. In 1878 Sir William Jenner went so far as to say that he would rather see his daughter dead than as a medical student. Yet the history of women in medicine is one of stubborn, dedicated individuals who refused to allow considerable obstacles to put them off their chosen course.

The effect of a female doctor on a young man’s heart rate was a cause for concern to Punch in 1865.

Elizabeth Blackwell of Bristol (1821–1910) was the first woman to have her name included on the Medical Register, in 1859, but her training and career were in America and it was Elizabeth Garrett (1836–1917) who became the first registered English female doctor, in 1865 (see apothecary). The Medical Register had only made its appearance in 1859, following the Medical Act 1858 that required all those practising as physicians, surgeons, doctors or apothecaries to have followed a recognised course of study and be registered by the Medical Council.

Many early women doctors gained their degrees from universities in Zurich or Paris. In 1869 Sophia Jex-Blake (1840–1912) managed to be accepted into the School of Medicine at Edinburgh Infirmary, although the authorities would not allow her to qualify. The situation only eased a little with the founding of the School of Medicine for Women in Brunswick Square, London in 1874, and the establishment of the Hospital for Women in the Marylebone Road by Dr Garrett, and the Edinburgh School of Medicine for Women by Dr Jex-Blake, allowing women to get the practical experience they needed.

In 1876 an act allowed qualifying bodies to grant medical registration ‘without distinction of sex’, but added the rider that nothing in the act made it compulsory to open their examinations to women. Some schools of medicine followed the spirit of this permissive act and admitted women students, including the Kings and Queens College of Physicians in Dublin and the schools of the Royal Free Hospital and London University, but many did not. The Birmingham University Medical School’s first female medical student matriculated in 1900 (even though the Women’s Hospital had ‘unlawfully but enthusiastically’ appointed a female Resident Physician in 1877 – Dr Louisa Atkins, MD Zurich); the School did, though, have the honour of training Hilda Shufflebotham, later Dame Hilda Lloyd (and then Dame Hilda Rose), who became the first female president of the university in 1949, and the first female professor of a medical royal college, in obstetrics and gynaecology (see www.medicine.bham.ac.uk). Manchester University’s first female graduate from its School of Medicine was Dr Catherine Chisholm in 1904.

Women were admitted as members of the British Medical Association in 1892, when there were about 200 female doctors in the country. Mary Emily Dowson was the first female surgeon to be registered (approved by the Royal College of Surgeons in Dublin in 1886) and Dr Eleanor Davies-Colley became the first female Fellow of the Royal College of Surgeons in 1911. Female doctors could be found in hospitals, workhouses, private practice, general practice and the operating theatre.

Women doctors were from the beginning sought after in certain countries abroad, particularly India. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries there were frequent appeals by the Medical Women for India Movement for qualified women to take up teaching and clinical posts in hospitals and clinics on the sub-continent, where millions of women either could not be treated by a male doctor for religious reasons, or lacked the money to pay for care, and where female students needed tuition and role models. In 1874, for instance, the Madras Medical College opened its doors to female students. This was a secular movement, separate from that of the missionary, societies (see missionary).

The names of female doctors will appear in the Medical Register. The Wellcome Library has a list of sources for ‘Women in Medicine’ (http://library.wellcome.ac.uk/doc_WTL039962.html), and the Guildhall Library’s advice on sources for finding surgeons, physicians and other medical practitioners is a good background guide to the profession (www.history.ac.uk/gh/apoths.htm).

The Royal College of General Practitioners (www.rcgp.org.uk/default.aspx?page=93) has advice for family historians, as does the Royal College of Surgeons of England (www.rcseng.ac.uk/library/services/familyresearch). The Royal College of Physicians (www.rcplondon.ac.uk/heritage/munksroll) has an index to obituaries, and the BMA (www.bma.org.uk/ap.nsf/Content/LIBBiographicalinformation) has biographical information. Outside England there is the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh (www.rcsed.ac.uk); the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Glasgow (www.rcpsg.ac.uk); and the College of Medicine at the University of Edingburgh (www.mvm.ed.ac.uk/history/history4.htm).

Domestic servant

Domestic service was a major employer of female labour until after the First World War, although unfortunately unless they were living in, finding out where a servant worked will be almost impossible. See under the job title, eg cook, housekeeper, lady’s maid, parlourmaid etc. There are many books about servant life, all of which have bibliographies for further reading. Try The Rise and Fall of the Victorian Servant, Pamela Horn (Sutton Publishing, 1995); Life Below Stairs in the 20th Century, Pamela Horn (Sutton Publishing, 2001); Below Stairs in the Great Country Houses, Adeline Hartcup (Sidgwick and Jackson, 1980); The Complete Servant, by Samuel and Sarah Adams, ed. Ann Daly (1825 edition reprinted, Southover Press, 1989); The Victorian Domestic Servant, Trevor May (Shire Publications, 2006).

Dressmaker

Dressmaking was another important employer of women and girls by the late 19th century – in the 1880s a third of the clothing labour force in London was in the trade, in one of its several guises. It could be a seasonal trade (busiest times were said to be March to July and October to November), with irregular hours according to the orders that had to be completed. The strict code of dress in Victorian times for mourning was one of the greatest supports of dressmakers large and small, as whole families might have to replace or adapt clothing at short notice; the death of public figures also ensured them a busy time. (Shroud-making was a sideline too – Ann Lee of Coventry was recorded as ‘dressmaker and shroudmaker’ in 1871.) The popularity and increasing supply of ready-made clothing changed the market over the turn of the century, with more hands being employed in factories or as outworkers, or in the large department or drapers’ stores.

A sleevehand in 1893 – garment-making was often broken down into its separate parts and each woman worked only on her section.

At the peak of the profession were the high-class Court dressmakers, creating fashionable clothes for society women and for debutantes who were to be presented at Court. The Royal Archives website (www.royal.gov.uk) states categorically that: ‘Court dressmakers were the people who made clothes for members of the general public who attended functions at Court, rather than specifically for the Queen or other members of the Royal Family’; unless of course they also held a Royal Warrant. This was what you might call ‘the Madame dressmaker’. One famous Court dressmaker was Madame Clapham (1856–1952) of Hull, who forged an enviable reputation in the 1890s and 1900s (see www.hullcc.gov.uk/museumcollections, and some of her beautiful creations can be seen online at www.mylearning.org). After the First World War the demand for such elaborate dresses began to decline. A Court dressmaker’s business could be very profitable, but behind the luxurious façade a small army of poorly paid workroom seamstresses and apprentices might have to work night and day to complete orders on time.

Dressmakers were employed in quantity by department stores such as Peter Robinson’s or Selfridges, where the rates of pay were better than working for a Court dressmaker in a smaller establishment. In some cases the girls lived in at the shop: ‘The “young ladies” resident in the houses of the higher firms, such as Messrs Howell & James, Regent Street, Messrs Lewes & Allenby, etc, are thoroughly well cared for, the salaries varying, according to capability, from £20 to £200 a year’ (Girl’s Own Paper, 1883). Most made-to-measure work was done by hand, ‘machinists’ normally just stitching linings. A large part of their work was altering clothing for customers.

A dressmaker might work on her own account, taking in orders from private clients and working at home – particularly a married woman who had had to give up work. She might also be a ‘visiting dressmaker’, going to the homes of clients and working there for a few hours a week: ‘A visiting dressmaker receives from 2s to 2s 6d a day, and her principal meals are provided for her’ (Girl’s Own Paper, 1883).

Girls leaving school were usually taken on as apprentices. The period of training with a Court dressmaker might be two years, or anything up to five years for a big store. The conditions of the apprenticeship could vary – sometimes the girls were paid nothing for a year, their parents having to find a premium for them to be taken on. In the 1930s an apprentice in Cumbria was paid 4s 6d for a 40 hour week, in comparison to a fully qualified dressmaker at 29s.

One girl who was apprenticed to the dressmaking department of Richmans, an exclusive store in Walsall, in the 1920s, found her first job was picking pins up off the floor and taking out tacking thread. The room the girls worked in had treadle sewing machines, a coke stove for heating the flat irons used to press clothing, and a gas ring for the very heavy iron that was used to press bigger items such as coats. The discipline was strict and all work took place at large tables covered with brown paper. Each girl was trained either as a ‘skirt hand’ or a ‘bodice hand’. This division of labour was common (caused partly by the increasing complexity of women’s dresses in the later 19th century and partly by the sewing machine, which instead of freeing women simply gave them ever more complicated work to do) and being a dressmaker did not necessarily mean that she worked on whole garments.

The women at the bottom of the trade were those who were employed in the background – the ‘sweated labour’ that periodically throughout the 19th century was highlighted as a shameful affront to those who bought fashionable clothes (see also tailoress). Anyone called simply a ‘seamstress’ is likely to have been in this category, employed at starvation wages in dreadful conditions, sometimes at home, sometimes in sweat shops, working 14 to 18 hour days.

The website www.fashion-era.com/the_seamstress.htm has a lot of background information, about the profession as well as every aspect of clothing. A study of any fashion book covering the period will provide a good idea of the clothing over which dressmakers laboured; e.g. A Visual History of Costume: The Nineteenth Century, Vanda Foster (Batsford, 1992), or Everyday Fashions of the Twentieth Century, Avril Lansdell (Shire Publications).

Dyeworks

Before 1856 all dyes came from natural sources, but in that year William Perkin discovered a method of factory mass-production that gave rise to the synthetic dye industry. His first colour – mauveine, a deep, intense purple – was so successful that Queen Victoria appeared in a gown of that shade in 1862, and the industry went from strength to strength until it hit a slump in the 1920s and 1930s. Women and children were employed in the industry, as unskilled labour and particularly in the bleaching process (see bleacher).

The Colour Museum of the Society of Dyers and Colourists (Perkin House, 82 Grattan Road, Bradford BD1 2JB; website: www.colour-experience.org) has some material on those involved in the industry and photographs, and the University of Bradford has a ‘Dyeing Collection’ (www.bradford.ac.uk/library/special/dyeing.php). More detail on modern dyes is available at www.makingthemodernworld.org.uk

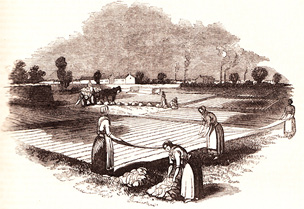

The bleaching ground at Monteith’s dyeworks, Glasgow in 1844. After cotton cloth had been bleached ready for dyeing it was brought out by women to the bleach-fields in 28 ft lengths and laid flat on the grass for a few hours to oxidise. If it rained, all had to be quickly gathered up. There were sometimes as many as 5,000 pieces lying on the field at one time.