T

Tailoress

A ‘tailoress’ might be a specialist in the making of women’s tailored clothing, such as riding outfits, outdoor cloaks etc. The advent of the ‘tailor-made’ from the late 1870s – a costume for women that was more severe and masculine than had been seen up till then and which was ideal for the New Woman to wear to the office or other work – meant that the line between dressmaking and tailoring became more blurred.

Tailoresses were also employed in ‘steam tailoring’, mass producing men’s ready-made clothing in factories, from the late 19th century. David Paton visited Leeds in 1893 for Good Words, finding that a single factory could turn out over a million garments – coats, jackets, waistcoats and trousers – a year. Some of the factories were huge, employing over a thousand workers, while smaller concerns used outworkers. Women worked as pressers and machinists, making up clothes on treadle machines driven by steam power, and each specialising in one task: some only did button-holes, making about 1,500 a day. They were paid by the piece and wages were anything from 15s to 30s a week. For better quality clothing, hand-sewing was still common.

Robert H. Sherard also went to Leeds in 1896, but he saw the ‘sweating dens’, where women worked in terrible conditions for up to 17 hours a day. Miss Clowes was a young girl he met who had ‘broken down in health, after trying for years to maintain her mother, three brothers, and herself on the 15s a week which she was earning’, out of which she had to pay 1s 3d for her thread and machine needles (the ‘sewings’).

A woman listed as a ‘tailoress’ in the census may, therefore, also have been one of the army of sweated workers who worked on shirts, trousers and other men’s garments in small workshops or their own homes. The select committee that investigated the Sweating System 1888–1890 interviewed several of these women in London. One was Mrs Lavinia Casey, who was making shirts at 7d the dozen, working from seven in the morning to eleven at night as well as looking after her children, and from her low weekly earnings she had to deduct 2s 6d for the hire of a Singer sewing machine and about 1s for machine oil and thread.

See also dressmaker for fashion sources.

Tambourer

A tambour was a frame on which cloth, particularly muslin, could be stretched so that the tambourer could embroider with a needle from both top and bottom – just as tapestry frames or needlework hoops work: ‘It consists simply in drawing the loop of a thread successively through other loops, in such a manner as to allow the thread to stand out prominently on the muslin, to form a pattern, and yet to adhere durably to it’ (Penny Magazine, 1844). The frame could be quite large, so that several people could work at the same time, and in the early 19th century this was a female home industry, very common in Scotland. The women were supplied with the muslin by a middleman, who purchased from them the finished product, often used for collars or cuffs. By the mid-1800s, a machine had been invented which could be worked by three women yet do the work of dozens, but the hand craft continued in some areas.

Telegram girl

Sometimes girls rather than boys were employed to deliver telegrams – one woman recalled being paid 5s a week at the West Malvern post office in 1919: ‘While I waited for the telegrams I did housework and mending for the postmistress.’ See Post Office.

Telegraphist

The electric telegraph was first used commercially in 1843 and its importance grew alongside the railway system, promoted particularly by Brunel’s Great Western Railway in Bristol. By 1854 the Electric Telegraph Company was employing female clerks to work the telegraph (which Punch greeted as a ‘happy idea’, given the ladies’ ‘love of rapid talking’). In February 1870 the government took over all the private telegraph companies and gave this new state service to the Post Office to run. The impact of the telegraph on communications in the 19th century has been likened to that of the e-mail in the 21st century – it must have seemed like a minor miracle to have a message arrive at its destination almost instantaneously by means of wires strung across the country, not to mention being able to send words across the oceans of the world.

Anyone who wanted to send a telegram (or a ‘wire’, as it was sometimes called) went to a post office and wrote out their message on a special form, which they handed over the counter. Payment was according to the number of words, so messages tended to be brief and to the point. In large post offices the form would then be rolled up into a little box, placed in a pneumatic tube and sent by means of compressed air to the operator. She worked at a keyboard, using a knob or ‘key’ to tap out the message letter by letter in Morse code. It would be decoded at the receiving office, and the message delivered in person in the form of a telegram by one of the Post Office’s small army of telegram boys (or girls). That was the system at its simplest, though technological advances were as keen in the telegraph industry as they were everywhere in the Victorian era.

Some telegraphists worked at ‘receiving houses’ – shops that acted as agents for the Post Office – but were poorly paid. Far better to work for the Post Office at any of the provincial telegraph stations, or at the Central Telegraph Station at Blackfriars in London. The pay was slightly higher (though not generous), overtime was paid, there was scope for promotion to supervisor, and, as civil servants, the women would qualify for a pension after 25 years (if they did not marry, when they would have to give up their job). Girls aged 14 to 18 were allowed to take the Civil Service examination, entering as probationary clerks. A good basic education would see them through, and knowledge of a foreign language was an advantage in the larger stations.

Women telegraphists at the Metropolitan Gallery of the Telegraph Offi ce in 1871, soon after the service had been taken over by the Post Office – ‘lady-like labour’ that opened up new employment possibilities for middle class girls.

By the late 1880s over 30 million telegrams were being sent each year – the introduction of the ‘sixpenny telegram’ in 1885 brought a sharp rise in demand. Over 700 women were employed in the main London station alone. The busiest times for the girls were said to be from 10 am to 1 pm, when the Stock Exchange and the betting world were busy, and after 6 pm when the wires hummed with Press reports for the next day’s newspapers. In London they were linked also to the foreign cable companies, and to the House of Commons by two miles of pneumatic tube.

The telephone would eventually supersede the telegram. Perhaps the most evocative use of the latter was during the two world wars, when the arrival of a telegram at the front door was usually the dreaded prelude to tragic news. See Post Office.

Telephonist, telephone operator

When Alexander Graham Bell demonstrated his new invention to Queen Victoria in 1877, no one could have foreseen that in 50 years time over one and a half billion telephone calls would be made in one year in the UK alone. The number of telephones in private homes and in offices grew steadily, from a slow start when the telegraph still held the ascendancy, and by 1912 there were nearly 3,000 telephone exchanges and over 700,000 telephones already in the system. There was no direct dialling and every call had to go through a local switchboard exchange until automated exchanges gradually replaced them between the wars.

Thousands of women were employed as telephonists – until the end of 1911 – by the National Telephone Company (which had itself merged in 1889 with other early pioneers such as the United Telephone Company and the Lancashire and Cheshire Telephone Company) and the Post Office (GPO). On 1 January 1912 the GPO took over the entire telephone system and all the exchanges; by 1981 the telecommunications section had become so vast that it was made into a separate public corporation by the government and British Telecom became a private company in 1984.

It was a job that seemed especially suitable for women – clean, sociable, and with ‘prospects’ for a career if necessary and a pension at the end of it. ‘The National Telephone Company recruit their operators from the ranks of bright, well-educated, intelligent girls, who are, in many cases, the daughters of professional men, doctors, barristers, clergymen and others,’ wrote Henry Thompson in 1902 (Living London). From the callers’ point of view, the pleasant and friendly voices, calm and reassuring manner, and helpfulness of the girls made a big impression. When they picked up their telephone in their home or office and dialled for the operator, a light came up on the switchboard in front of the telephonist. She plugged into the number, received the order, and made the connection. The exchanges eventually varied in size from the large and bustling hall-like rooms of the cities, to the small village exchange run in her own front room by the local postmistress.

Both the NTC and GPO employed girls from the age of 16, of a minimum height (5 ft 3 ins for the NTC, 5 ft 2 ins for the GPO) and in good health – any girl taken on by the GPO was ‘examined by a lady physician, her eyesight tested, her teeth put in order – to avoid absence through toothache – and, if considered necessary, revaccination follows’. Girls were employed first as learners on about 10 shillings a week, with a probationary period of two to three months, and pay then rose annually to £1 a week; promotion was also a possibility, to swupervisor, or to clerk-in-charge (at £85 to £170 per annum in 1910). The NTC allowed the girls to wear gloves, ‘to better maintain the contour and complexion of their busily worked fingers’, and to cover their dresses with ‘a loose kind of graduate’s gown in dark material’ so as to ‘shield a sensitive and modestly-garbed operator from being distracted by an extra smart frock on either side of her’. The GPO must have believed their girls were made of sterner stuff and had no such dress sensibilities.

If a girl married, she was expected to leave her employment. Perhaps there were some compensations, though: one commentator in 1910 wrote that ‘the work of the telephone operator is healthy, and the action of stretching her arms up above her head, and to the right and left of her, develops the chest and arms, and turns thin and weedy girls, after a few months’ work in the operating room, into strong ones. There are no anaemic, unhealthy-looking girls in the operating rooms’.

Telephonists working at the Central Telephone Exchange, St Paul’s Churchyard in the early 1900s.

It was a responsible job, especially in time of emergency or danger. Telephonists were essential workers during both world wars and many put their lives at risk by working on during air raids to keep the lines open. Lilian Ada Bostock, for instance, was awarded the BEM in 1918 for ‘displaying great courage and devotion to duty during air raids’. The GPO took over the staff of the NTC in 1912 and the records relating to telephonists who left before 1959 are still in the archives (see Post Office).

Tobacco worker

Female labour was used to a great extent in the tobacco industry ‘whatever form it takes, cake or flake, Cavendish or bird’s eye, snuff, cigar or cigarette’. Loose tobacco had been profitable since the 17th century, most usually smoked by all classes of society in the ubiquitous clay pipe, or chewed, while taking snuff (finely ground tobacco, blended with perfume or herbs) was mostly an upper class habit. Cigars (or ‘seegars’, as the first Cuban imports were called) became popular with the upper classes during the early years of the 19th century, and cigarettes were a French innovation that reached Britain in the mid-1800s – the first cigarette factory was opened at Walworth in 1856.

At that time, too, new companies were established to feed the demand, many of them still familiar names such as W.D. & H.O. Wills in Bristol (1830) or Ogdens in Liverpool (1860). By 1900 smoking was such an established part of life that smoking jackets and hats had become popular for the aspiring middle class man, as well as the after-dinner cigar. Many large towns and cities had their own tobacco factories, such as Chester, which in 1910 had five manufacturers. From 1900, faced with aggressive competition from America, the major manufacturers banded together to form the Imperial Tobacco Company, beginning a process that saw the gradual reduction of the number of individual companies to three by 1980.

In some cases in the 19th century girls were employed from a young age as apprentices in the factories, hand-making cigarettes. Later, women were employed as low-paid machine operatives, once the larger companies began to install cigarette-making machinery from the 1880s.

A girl at Messrs Cope’s factory at Liverpool in 1896, sorting the leaves taken from a hogshead of tobacco.

In the early 1900s, for Living London, C. Duncan Lewis visited ‘the great tobacco factory belonging to Messrs Salmon and Gluckstein, Clarence Works, City Road’. In one room he watched men making cigars. ‘In the next room women are just as busy. These are stripping the stalks from the leaves; those are sorting the leaves for quality; to the right, men are employed in preparing the leaf for the cigar maker. In other rooms you find girls busily engaged in banding, bundling, and boxing cigars, which are then passed on for maturing. In an adjoining department cigarette making is in progress on a colossal scale, and many machines are here running at a high rate of speed, producing huge quantities of cigarettes hourly. Apart from these machines, very large numbers of men and women are engaged in making cigarettes by hand.’

Some companies have produced their own histories, e.g. John Player & Sons: Centenary 1877–1977 (John Player & Sons, 1977). There is a tobacco museum at Sutton Windmill and Broads Museum, New Road, Sutton Vale, Norwich, NR12 9RZ (www.yesterdaysworld.co.uk). Papers of the Tobacco Workers’ Union are held at Warwick University (www.warwick.ac.uk/services/library/mrc/ead/101tw.htm). See www.history-of-tobacco.com for background on tobacco and smoking.

Tracer

An office has lately been established in London by ladies for tracing the plans of architects and engineers, a new branch of art-work, which has been found a successful opening. Lady-apprentices must, however, give three months’ work without wages, and even at the end of the first three months the earnings are but small; the inducements held out are not, therefore, very great.’ (Cassell’s Household Guide, 1880s.) However, tracing maps and plans became a female branch of employment, working with male draughtsmen or cartographers. In 1902, for instance, the Ordnance Survey employed women for the first time, to mount and colour maps.

Women were employed particularly in the engineering industry to make draughtsmen’s plans into production drawings ready for the factory, often working with Indian ink on linen. An all-female trade union was formed – the Tracers’ Association – which, in 1922, amalgamated with the Association of Engineering and Shipbuilding Draughtsmen. By the time of the Second World War, the trade of Tracer was held by members of the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force (WAAF) and the Auxiliary Territorial Service (ATS), the latter working with the Royal Army Ordnance Corps to produce drawings of new designs for tools and parts for tanks and lorries.

Trade unionist

From the 1880s women’s trade unions or associations were being formed and many women were taking an active part in political activity for the first time. Mark Crail’s website (www.unionancestors.co.uk) lists some of the thousands of trade unions that have been in existence since then and is an excellent starting point for pinning down which ones would have been active in an industry at a particular time.

A few women found paid employment with their union. Anne Godwin (1897–1992), for instance, the daughter of a draper, trained as a shorthand typist when she left school in 1912. After the First World War she joined the Association of Women Clerks and Secretaries (AWCS) and in 1925 began working in their offices, becoming a full time union official in the 1930s. She successfully negotiated an amalgamation with the male National Union of Clerks in 1940 and in 1956 became General Secretary of the union; in 1961/2 she was only the third woman to be President of the Trades Union Congress (TUC) and was made a Dame of the British Empire. (Her predecessors at the TUC were Anne Loughlin of the Tailors and Garment Workers Union in 1943 and Florence Hancock of the Transport Workers Union in 1948.)

For an introduction to the subject see the online exhibition ‘From kitchen table to conference table’ at www.politicalwomen.org.uk. This was put together by the Working Class Movement Library (51 The Crescent, Salford M5 4WX; www.wcml.org.uk) and their archives include biographical material. Today’s trade unions’ websites are also useful in disentangling their sometimes complicated life stories, e.g. www.tssa.org.uk for railway workers.

Trimming maker

see hat maker; milliner.

Trotter seller, trotter scraper

Sheep’s trotters were a form of fast food available on the streets of London, Liverpool, Newcastle upon Tyne and other cities in the Victorian period. They were a by-product of the leather industry and had originally been sold wholesale for use in glue manufacture but by the 1850s there was more profit in selling them for food. Henry Mayhew describes one establishment in Bermondsey where women were employed to scrape the hair off the trotters ‘quickly but softly, so that the skin should not be injured, and after that the trotters are boiled for about four hours, and they are then ready for market. . . . One of the best of these workwomen can scrape 150 sets, or 600 feet, in a day, but the average of the work is 500 sets a week, including women and girls. . . . they were exceedingly merry, laughing and chatting . . .’. Those who sold on the streets were mainly elderly women, with a hand-basket and a white cloth on which to display the trotters (see street seller).

Typist, typewriter

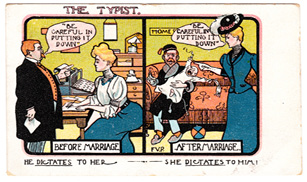

The original name for a woman (or man) who used one of the new office machines in the 1880s was a ‘typewriter’, becoming the modern ‘typist’ by the 1900s. A copy typist simply typed up letters and other documents, while a shorthand typist, on a higher wage, would be required to type up from dictation, and both occupations grew hugely in number from the late 19th century (see office staff); either might work for an individual or be in the typing pool and on call for a number of men. By the 1930s there were some 200,000 women typists in Britain

A warning to enamoured businessmen, dating from 1908.

An article in Woman’s Life in 1896 described the foundation of the ‘shorthand and typewriting office’ in the Houses of Parliament, opened 18 months before for the convenience of MPs and under the direction of Miss May H. Ashworth, a rector’s daughter, who also ‘manages, and has done so for many years, a large office in Victoria Street’. Her girls had been given apartments adjoining the House of Lords, complete with ‘electric light and every modern convenience’, under the supervision of the Sergeant-at-Arms. Miss Ashworth, who is a good example of the kind of female businesswoman taking advantage of the new opportunities for educated women in the late 19th century, trained the girls herself in ‘a school which I have established in connection with my business . . . all of them are able to write 120 words a minute, or more, in shorthand, and an average speed of 80 words a minute on the typewriter’. This was at the higher level of expertise; Civil Service examinations for shorthand typists in the early 1900s required only up to 100 words a minute shorthand and ‘1,000 words an hour’ on the typewriter. Their starting salary was 25 shillings a week, rising with experience.