CHAPTER FIVE

WITHIN the LABYRINTH

Eastward again to Iraklion, official capital of Crete since 1971. After the attractive harbor towns of Chania and Rethymnon, which are easy to explore on foot and still retain vestiges of a traditional way of life, most of Iraklion is sprawling and featureless. The city suffered extensive damage from bombing raids during the Second World War, and the postwar reconstruction was carried out in haste, without much planning and without much care for style.

Despite its present prosperity—this is the wealthiest region of the island—Iraklion has an unmistakable look of lost function, of a city somehow sidetracked, traduced by history. This is a sad condition and one difficult to demonstrate by example, but it is summed up by the vast Venetian harbor and the great fort that guards its entrance. A fleet of Venetian war galleys could have anchored here once, under those protecting cannon. Walls and fortifications are still in place. But the harbor cannot accommodate modern vessels. Even the ferryboats plying to the mainland—the main traffic by sea—have to dock at the massive, and massively ugly, concrete wharves nearby. The arsenals and shipyards the Venetians built are lost in a sea of traffic.

Iraklion: the Venetian fortress

The city’s history, and that of Crete as a whole, is written in its successive names. The original village was named after Herakles, the mythical Greek hero and strongman. In the ninth century the invading Arabs built a fortified town here, which they called Khandak, the Arabic word for the kind of large moat that formed part of the town’s defenses. This became Chandrax for the Byzantines, who expelled the Arabs in 961, and Candia for the Venetians, who took over the island in 1204. The original name was not restored until early in the twentieth century, after the last of the Turkish occupying troops had been sent packing. It was as Candia that the city enjoyed its greatest power and prestige becoming one of the great cities of Europe, an important trading post and outfitting center for the Crusades. And it was virtually impregnable. Whatever the shortcomings of the Venetians, they knew how to build forts: Even when the Turks controlled the rest of the island, they took another twenty-one years to conquer this last bulwark of Christianity in the eastern Mediterranean—probably the longest sustained siege of any city in recorded history.

We lost some time on an unsuccessful quest for a reasonably good bookshop. It seems somehow significant, somehow typical, that a city this size, with something like 100,000 inhabitants, capital of the island, didn’t have one. Crete does not abound in them anyway, but there are better ones at both Chania and Rethymnon. Put out by this failure, I tried gloomily to remember when, if ever, I saw a Cretan reading a book. I was brought to regret these unkind thoughts when the bookshop where I had asked for a book obtained it for me in three days and phoned to tell me it had arrived.

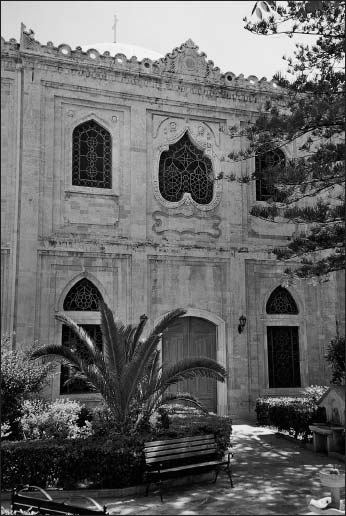

The Church of St. Titus, at 25 Avgoustou Street, near Kalergon Square, sums up in its architectural history the ebb and flow of power on the island. Titus was a disciple of St. Paul the Apostle, who appointed him first bishop of Crete. His church in Iraklion was founded by the Byzantines, taken over and rebuilt by the Venetians, turned into a mosque by the Turks, restored by them after the earthquake of 1856, renovated by the Orthodox Church after the Turks had departed, reconsecrated in 1925.

Quite a checkered career. But through all these vicissitudes, we discovered one object that has survived in its pristine state, and that is Titus’s skull, which has been preserved as an object of devotion—the rest of his body was never recovered. True, the skull has traveled about a good deal. Until the early Middle Ages it was kept in the ancient basilica at Gortyn, also dedicated to the saint; then it was moved to Iraklion; then—out of fear of the invading Turks—transferred to Venice and kept there for some centuries. Finally, in 1966, it was restored to the capital and reposes in a reliquary in this quiet church, free from further threats and alarms, or so one hopes.

Iraklion: The Church of St. Titus

We found other things too that have escaped mutilation. The Christians pulled down the minaret and surmounted the dome with a cross, but in the small courtyard in front of the church the unpretentious Ottoman fountain still keeps its place, with its exquisitely carved stone, its channel for the washing of feet, and outlets for running water—always running water for the Muslim lustration. The fountain is beautiful, and it has survived by virtue of its modest dimensions—there is a lot to be said for keeping low to the ground.

The churches of Crete can be a guide to the labyrinth of history even when they have long ceased to be buildings at all. The Monastery of San Francesco exists no longer, but it was once the most imposing Catholic foundation on the island, built by the Venetians in the first century of their rule. Now Iraklion’s Archaeological Museum covers the site. But it has not vanished altogether. While it was still being used as a mosque, the severe earthquake of 1856 brought most of it down, but Turkish troops rescued the door frame and built it into their barracks, for reasons not clear, perhaps in the hope of Allah’s blessing, though it was a Christian door frame originally, having been donated to the church in 1410 by Pope Alexander V, a Cretan named Petros Philargos, who, according to some sources, had previously been a monk at the monastery. There were no less than three popes at that time and considerable doubt as to who was St. Peter’s legitimate heir. Alexander died after only ten months in office, a mysterious death—many believed he had been poisoned by his successor. The barracks crumbled away in their turn, but the door survived: It now serves as northern entrance to the law court on Dikeossinis Street and must have witnessed the passage of a good many malefactors. Five hundred years and a mystery or two, all in the span of a door frame.

The Church of Agia Ekaterini on the square of the same name, which we arrived at going westward down Kalokerinou toward the Chania Gate, has been put to a use which—like the former mosque inside the fortress walls in Rethymnon and the former Church of San Francesco in Chania, now a museum—makes very good sense indeed. Formally a celebrated monastic academy and art school, it is now a museum of religious art, housing a collection of Cretan icons it would be difficult to match elsewhere, in particular several by Michalis Damaskinos, a contemporary of El Greco, also Cretan, less famous than him but a very considerable artist, one of the first Cretan painters to introduce elements of Renaissance humanism into the severely formal tradition of Byzantine icon and fresco painting.

Agia Pelagia, a few miles west of Iraklion, is where a lot of people choose to stay who want to combine a beach holiday with trips to Knossos and various other Minoan sites in the vicinity of the city. The phrase “a lot of people” seems like an understatement in view of the multitudes that descend on the region at the onset of summer. The headland above the village is more or less entirely staked out by huge hotel complexes, places where you can easily get lost—it might take you a quarter of an hour to walk through the beautiful gardens from your chalet or villa or bungalow to the nearest place where you can get a cup of coffee, or find someone to tell you where a cup of coffee is to be got.

This is the exclusive, expensive face of tourism in Crete. The other face can be found below, in the continuous string of bars, discos, tavernas that front the narrow strip of beach and extend inland to a wilderness of car-rental agencies, fast-food eating places, supermarkets, and a jumble of apartment houses and small hotels and half-finished building projects. The roads designed to link these places haven’t had time yet to catch up. They too are often half finished, sometimes hardly started, sometimes ending in piles of rubble or vacant lots. The pace of development outstrips the maps, however up-to-date these may appear to be. What looks blessedly empty on the map turns out to be in full spate of building. There is a point, not easily measurable but nonetheless real, when the influx of visitors and the changes of structure needed to accommodate them passes from sustainable to destructive. And it is a point of no return. The anthropologist Sonia Greger, writing in 1993, already sounded a warning note:

Tourism along the north-east coastal strip of Crete has, I would say, reached crisis stage with respect to the near break-down of traditional values, hospitality and sense of community…. One cause of crisis in tourist development is escalating competition between locals, as they throw out their traditional means of support and subsistence.

The larger, more expensive hotels overlooking the bay also cause damage to local communities, in this case by virtually depriving them of their own land. Extensive areas of the promontory, including large stretches of the shoreline, are closed off. By Greek law everyone has the right of access to the shore, regarded as common land. This is an excellent principle, but it is not applied in practice. The hotels have imposing gates and entrance driveways, and security guards to keep an eye on who comes and goes. Unless you are a guest or very good at bluffing, you are unlikely to get through. This means that a local inhabitant who once swam from these beaches, or kept a small boat for fishing, or walked on the cliffs and enjoyed the splendid views across the bay, and who was accustomed to regard these things as his birthright, has been—as the result of a stroke of the pen in some remote office—entirely dispossessed.

Such vast hotels are in any case founded on a wrong concept of what a hotel should be. “Megalux” is the effect aimed at. The “mega” is present in the hundreds of detached bungalows, in the acres of gardens, the vast, marble-appointed reception areas. But the “lux” part is lacking. The capital outlay has been enormous, the need to recoup very urgent. Package tours are the quick way to do this. For these hotels the ideal visitor is not a private person but a unit, a number, part of a package. A spirit of suspicion prevails. The guest must furnish himself with a card that has his category on it; without this he is lost, unable to reply satisfactorily to the hotel staff who are constantly asking him who and what he is. In one hotel with a five-star deluxe rating, one of the most expensive on the island, outside a breakfast room with seating for a thousand people, so large that one can hardly see across it, there is a notice in various languages requesting the guests not to walk away with the knives and spoons. The women who work as cleaners are routinely searched at the gatehouse before being allowed to leave.

At the entrance to the dining room an impeccably dinner-jacketed headwaiter, having glanced at our card, murmured that in our case meals were extra. We found out that—just as in the case of people who want to avoid being mugged on the street—you must look as if you know where you are going. As we wandered bemused among clumps of tamarisk and orange groves and volleyball pitches and Olympic-size pools and palatial conference rooms, a security guard in the dress of a Cretan bandit, festooned with weapons, emerged from the shrubbery and asked to see the card proving we were bona fide guests.

Lying just a few miles south of Iraklion, the magnet that draws so many people to this region of Crete is Knossos, indisputably one of the greatest prehistoric sites in the world. This is where the Labyrinth, which has exercised the Western imagination for millennia, is said to have been, though its real nature is still disputed. Some maintain that it derives from the Minoan habit of agglutinative building, adding rooms to already existing rooms till their houses and palaces came to resemble mazes—in that case, perhaps the palace of Knossos, which in its heyday had more than a thousand rooms on five floors, was itself the labyrinth.

Others argue that the name derives from religious practice. Labrys in Lydian means “doubled-headed ax,” which was an object of cult worship among the Minoans. So labyrinthos might mean “the place of the sacred ax.” Costis Davaras mentions the belief held by some that the real place of the labyrinth was not Knossos at all, but the cave at Skotino, some miles east of Iraklion. As already noted, it is difficult to pursue any line of inquiry regarding Crete, or take any route, without coming across a cave before long. This is one of the most impressive on the island, 530 feet deep, with a main chamber like the nave of a cathedral and winding galleries.

The theory I like most but believe least is that the labyrinth refers to Cretan dancing patterns. At the close of Book Eighteen of The Iliad, Homer describes a Cretan folk dance whose weaving motions make maze-like patterns that form and dissolve. Here it is in Robert Fitzgerald’s translation:

A dancing floor as well,

he fashioned, like that one in royal Knossos

Daedalus made for the Princess Ariadne …

Trained and adept they circled there with ease

The way a potter sitting at his wheel

Will give it a practised whirl between his palms

To see it run; or else, again, in lines

As though in ranks, they moved on one another:

Magical dancing!

Independently of the theories, the ancient myths have remained. The palace of Knossos was the heart of Bronze Age Crete; at the heart of the palace was the labyrinth; and at the heart of the labyrinth was the monstrous Minotaur. Here the hero Theseus came, here the king’s daughter Ariadne fell in love with him and gave him the ball of twine which helped him to find his way out after slaying the monster, here Daedalus the master artificer made the wings for himself and his son Ikarus so that they could escape from the maze. Ikarus, it will be remembered, flew so near the sun, the wax that bound his feathers melted and he plunged into the sea. The island in the Sporades where his body was washed up is named after him, Ikaria. A real island, a mythic punishment for human rashness …

The excavation of Knossos by the great British archaeologist Arthur Evans has itself by now passed into the zone of myth—at least, it has assumed that blend of fact and legend somehow characteristically Cretan. What led him to it seems to have been an accident of his own physical constitution more than anything else. Joan Evans, in her biography of him, tells us that he was extremely shortsighted. If he held things very close to his eyes he could see them in the most amazing detail, but at any farther distance everything was blurred. Not much of a blessing in general terms, but it enabled Evans to make out with phenomenal exactitude the hieroglyphics on the bead seals—an earlier form of signet ring—that he came across in various parts of the eastern Mediterranean. The Athenian dealers told him that most of these came from Crete. And it was in fact in Crete that he found them again. He could not decipher the signs, but he recognized affinities with Egyptian and Mesopotamian hieroglyphics. They brought him to the conviction, one which changed the whole course of his life, that on this island there had once existed a highly developed civilization, the remains of which still lay under the ground.

It is not given to many men, proceeding almost single-handed, acting on a solitary conviction and guided by a mixture of deduction and intuition, to demonstrate to the world the existence of a hitherto totally unsuspected civilization. It was given to Evans.

In March 1899 he recruited Cretan workmen and began digging into the mound of Kephala at Knossos. He was at first looking for further examples of the hieroglyphics he had found on the seal stones. He was never to succeed in deciphering these, but in a matter of days he realized that much more than hieroglyphics was involved in the enterprise. He was in the process of uncovering the remains of a palace complex vast in its extent, showing evidence of engineering and architectural techniques so advanced that they could only have belonged to a highly developed society. It was still commonly believed at the time that European civilization began with the Greeks, somewhere about the year 700 B.C. Evens realized he was being given the opportunity to supply a gap of 1,500 years in Europe’s knowledge of its own past.

Amazing things were unearthed at Knossos in these last months of the nineteenth century. An early find was a cup-bearer fresco, discovered in two pieces, the first representation ever brought to light of a young man of the prehistoric Cretan Bronze Age, the society that Evans was to call Minoan. Day by day the ground plan of the palace was uncovered: porticos, bathhouses, courtyards, stairways, the throne room with the throne of King Minos still in its original place. But perhaps the most remarkable find of all was the remains of a fresco showing a young man somersaulting, with incredible hardihood and acrobatic skill, over the back of a charging bull, and a girl standing with arms outstretched as if to catch him as he lands. In the months that followed they encountered this theme of bull vaulting again and again. The meaning still eludes us—at least it is still argued about, which comes to the same thing. Popular sport? Gladiatorial contest? Religious practice based on the worship of the bull? Or are the stories of human sacrifice true after all? Was one of these bull leapers the hero Theseus, as we find related in Mary Renault’s novel The Bull from the Sea?

Visiting Knossos by car these days confronts one with a different kind of puzzle—and yet another example of Cretan enterprise. Which is the official parking lot? On the last half mile or so of the road that leads to the site, we counted seven at least, competing for custom. The official one was free, the others were not, though they all had large and prominent and closely similar signs proclaiming their identity as the true Knossos CarPark. Only later, when we had been maneuvered into one of the cramped and rutted unofficial parks and paid for our ticket, did we both, simultaneously, realize the difference: The official parking lot was the one with the least conspicuous sign, and it had no person at the roadside in an official-looking cap waving and smiling and guiding you in.

To our dismay the site itself was swarming with visitors, many in large groups brought by tour buses, conducted by cheerfully positive guides who give out as established fact what must surely, after so long and on such sketchy evidence, be matters of speculation. “This was the queen’s bedchamber, and this was her dressing room, where the ladies-in-waiting attended on her….”

We clamber to identify the rooms, understand the layout of this vast place, more like a town than a single building, where monarchs and priests and artisans and slaves lived nearly four thousand years ago. A longish line of people are waiting for their turn to view the throne room, one of the most celebrated sights of Knossos. After ten minutes or so of gradual forward movement we reach the cagelike bars which, separate the anteroom from the throne room. We peer through the bars, straining to make out details in the dim interior: the pale, streaky-looking gypsum throne of Minos on the right, still standing on the spot where it was found, flanked by copies of the original frescoes of crouching griffins; the sunken bath, perhaps for ritual cleansing—Minos, it seems, was both priest and king; a sort of recess beyond, perhaps serving as a shrine, or perhaps … But now there sounds the voice of the latter-day priestess, guardian of the sacred precinct, who is keeping an eye on things from her bench in the anteroom: “Move along, please! Don’t stay too long at the viewing point!”

We have been allowed approximately thirty seconds. Shuffling forward again, we get trapped in a corner, surrounded by seemingly enormous Scandinavians, in our ears the loud and confident voices of various guides. Not panic, perhaps, but feelings of oppression certainly. We are in a modern version of the Knossos labyrinth, how can we get out? Here, as in a different way in those vast beach hotels that specialize in packages, being the solitary individual has its snags. Wandering about the ruins, trying to make head and tail of things, the single person gets hemmed in, confused by alien voices. The member of the group does not suffer this fate: He has the comfort of numbers, he occupies the space, he is with the others, listening to the same voice, looking at the same things.

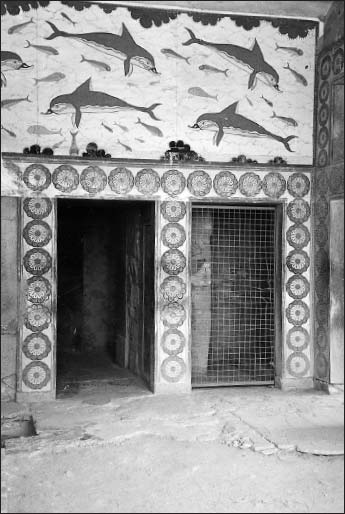

Knossos: the queen’s apartments

Very difficult, in such a crowd, to exercise the powers of imagination and intuition needed to feel the wonder of this place, get a sense of the remote society that once flourished here. We all get in one another’s way with our exclamations, our sun hats, our ungainly scramblings. Only at certain times, early in the morning, or during the hot middle hours of the day when the bus excursions have their scheduled lunchtime, the extraordinary nature of the place comes over one in a wave. The storerooms with their great earthenware jars for oil and grain; the workshops where the jewelers and smiths and potters made the objects for use and decoration never since surpassed for the quality of their workmanship and design; the royal quarters with their spacious, light-filled apartments; the vivid frescoes depicting people in their daily lives and all manner of birds and animals and flowers—dolphins, partridges, octopuses, lilies. Any of these things, even the smallest detail, can become a focal point for wonder, and one begins to understand what Pendlebury, who knew more about the palace of Minos than just about anyone else, meant when he wrote thus of its final destruction, probably due to a combination of earthquake, volcanic eruption on the nearby island of Santorini, and the onslaught of invaders: “With that wild spring day at the beginning of the fourteenth century B.C. something went out of the world which the world will never see again; something grotesque perhaps, something fantastic and cruel, but also something very lovely.”

One thing which makes Knossos different from all other Minoan sites on Crete is the reconstructions that were carried out by Sir Arthur Evans—as he by then had become—mainly in the course of the 1920s. In his passion for what he had discovered, his desire to protect the recently exposed remains from the weather, his wish to make the layout of the palace more easily understood by the visitor, he used the architectural details he found in fresco fragments to reconstruct some of the buildings, making use of bricks, metal girders, and cement to rebuild the columns and door lintels destroyed in those distant fires.

Knossos: Shield frescoes from the head of the grand staircase

This use of modern materials caused heated arguments at a time when there was a strongly romantic feeling about ancient remains. Evans was called the “builder of ruins” in the French press. Many people since then have felt that he went too far, that his use of the frescoes was too subjective. But there can be no doubt that he saved some important buildings from collapse, among them the grand staircase of the palace, regarded as unique in architectural history, with five flights of stairs still preserved in situ.

Unreconstructed, altogether less adorned and distinctly less crowded, are the palace of Festos, second largest of the Minoan palaces, overlooking the bay of Mesaras on the south coast, and the smaller palace of Agia Triada two miles nearer the coast. These are sites rich in archaeological interest with superb views over the plain of Mesara to the Libyan Sea. I am not by nature very exacting when it comes to exploring ancient remains. It doesn’t really give me any great satisfaction to know whether this niche or that was actually the family shrine, or precisely how high the staircase was, or—in any detail—how the water pipes were all joined up. I would only forget these things again. Making precise identifications on these Minoan sites is a headache anyway, for clues are scanty, and on-site information even scantier. Wandering here on a summer morning with the evidence of ancient life all around one, the olive groves and vineyards covering the plain below, the majestic peaks of Psiloritis rising to the north and the warm breath of Africa against your face—it is difficult to imagine a pleasanter way of spending an hour or two.

In 1908, inside a small chamber at Festos, one of the most famous finds in the history of Minoan excavation was made, the disk of baked clay, later to be known as the Festos Disk, dating from around 1700 B.C. Its provenance is still disputed, but the evidence indicates that it was made in Crete. At present housed in the Archaeological Museum of Iraklion, it is something truly to marvel at, a solid disk roughly six inches in diameter, completely covered back and front with ideographs inscribed in spiral form from the circumference to the center, 241 signs in all, among them running figures, heads crowned with feathers, ships, shields, birds and beasts and insects, each one impressed with great care on the wet clay using some kind of stamp. And all this several thousand years before Gutenberg!

Despite a century of efforts to decipher the script, no agreement has yet been reached. Various theories have been advanced. Was it a hymn to the Lord of the Rain, a set of building instructions, a list of provisions for the army, an anthem to a pantheon of gods? Some pretty unlikely solutions have been offered. At different times, linguists have sought to demonstrate that the text derives from Basque, or Finnish, or Magyar.

The road back to Iraklion branches northward at Agii Deka, and soon afterward runs past the ruins of ancient Gortyn, which was a Minoan city but saw its greatest power and importance in the classical period, first under the Greeks and then under the Romans. Three momentous landings outline the story of the city, the first of them—naturally, since this is Crete—mythological. Zeus, having fallen in love with Europa, a daughter of Agenor, king of Tyre in Phoenicia, assumed the form of a beautiful white bull. He seemed so gentle, the girl was enchanted by him and was eventually persuaded to climb on his back. Before she knew what was happening, she was riding out to sea, on the way to Crete. He brought her to Gortyn, where they became lovers. One of their three sons was Minos, whose throne room we got a thirty-second view of at Knossos. Crete then, not only gave Europe its name, it was where Europe began, a truth Cretans have always known.

The second landing occurred in the first century A.D., that of Titus, the disciple of St. Paul, who appointed him first bishop of Crete and gave him the task of overseeing the early Christian church on the island. “For this cause I left thee in Crete,” the Apostle says in his Epistle to Titus, “that thou shouldst set in order the things that are wanting.” Paul’s opinion of the Cretans, as we have seen, was not very high. Titus was martyred at Gortyn, and the ruins of the sixth-century basilica of the cross-in-square type that was built on the site of his martyrdom are among the most impressive to be seen here, with three apses and a section of the vaulting still standing. Under the Romans Gortyn became capital of the province of Crete and Libya, with a population of a quarter million, and it continued in wealth and importance under the Byzantines, who took over the island in A.D. 330.

The third landing—and the last—was that of the Saracens in A.D. 825. In accordance with their general policy throughout the island, they visited the city with fire and sword, and it was never rebuilt.

Legendary beginnings, a period of glory, total devastation—it is a familiar paradigm in the history of Crete. There is an abiding desolation in the remains of Gortyn that I have not felt elsewhere among the ruined cities of Crete, probably due to the huge area over which the ruins are spread. They extend on either side of the road, acre after acre of them, through thickets of bramble and choked ditches and plowed fields and olive groves. The local people have used the marble of temples and the granite of churches to repair their walls. Gortyn, especially on the south side of the road in the area bordering the River Mitropolitanos, provides a striking example of a universal process: the reversion of buildings to ruins and ruins to rubble and rubble to dust. This feeling gives a melancholy to the place and seems to rub away the distinctions of time and period: The ruins of the Roman governor’s palace, or of the Greek temple to Pythian Apollo, seem no older than the broken walls of an abandoned sheep pen. It is the same with people: The dead belong to one state and one period only.

To rescue one from melancholy, there is always the vitality and warmth of the people and the unfailing charm of the landscape, which can turn the accidental or unplanned into memorable experience. The region northwest of Gortyn is spectacularly beautiful. One day, in an attempt to go on foot from the village of Vorizia to the Valsamonero Monastery, we took a wrong turn. We realized our mistake after a while, but continued along the track we were on, impelled by the wildness and purity of the light among these hills—like the first light of the world—and by the play of shadow on the mountain peaks to the north, still capped with snow. The olive trees were in flower and the air was full of birdsong. Incredibly ancient, these olives, the trunks twisted and gnarled into tormented shapes. Seeing them, it is easy to understand the pervasive stories of metamorphosis found in Greek myths and in the Latin poets who inherited them. Poems of escape from death or ravishment, last-minute rescues by some suddenly compassionate god, plants struggling to turn into humans, humans striving to find escape in plants.

The olive was already cultivated on this island two thousand years before Christ. It is easy to believe, seeing these time-wrenched shapes, that some of the present trees go back that far. They don’t, of course, not quite, but one of the oldest olive trees in Europe is on Crete, at Loutro in Sfakia, with annual rings that date to well over two thousand years ago. Any olive with a diameter of seven feet or so will go back to the Middle Ages.

The path climbed up into the hills and there were ravens nesting in the crags above us and a kestrel circling below and, above the olives, great spreads of the splendid Greek fir, which you rarely see at altitudes of less than two thousand feet. This tree is dedicated to Pan, god of shepherds. He and Vorias (the North Wind) were both in love with a nymph called Pitys. She chose Pan as being less blustering and turbulent. In revenge Vorias blew her off a cliff. Pan found her dying and transformed her into his sacred tree, the fir, which was called Pitys in memory of her. Since then she cries every time the north wind blows, and her tears are the drops of resin that drip from her cones in autumn.

We tramped for a good many miles that day and were given a handful of oranges when we came to lower ground by gravely courteous people who quite clearly thought we were out of our minds to be clambering about when there was no need. I thanked them in Greek, which may at least have served to reassure them that we were not from some altogether different planet. Dusk fell, there was no time, we didn’t see the Valsamonero Monastery, with its fifteenth-century frescoes, painted by Konstantinos Rikos and said to be among the finest in Crete. But the monastery gave us a great trip and one can’t ask more than that. As the Alexandrian Greek poet Kavafis says in his poem about Ithaka, the kingdom of Odysseus, who found his way back there from Troy after many adventures, it’s no use asking anything from the island when you finally arrive: It has already made you the supreme gift of the journey.

There is one monument at Gortyn which has endured in much the same way that the olive trees have, strongly rooted like them. When the Odeon, or Covered Theater, was built here about A.D. 100, in the time of the Emperor Trajan, a much older wall was incorporated, as it had been incorporated in a succession of earlier buildings—a wall inscribed in Dorian Greek with a code of laws dating from the fifth century B.C. Over six hundred lines in length, the script reads one line from left to right, the next from right to left, so that the eye can follow the text continuously. It is the first codified system of laws known to Europe and one of the most amazing documents in existence anywhere.

Not that it illustrates the principle of equality before the law, so dear to us today, and even today more common in the breach than the observance. These are the laws of a society that was still tribal, still governed by rigid distinctions of caste. For rape committed against a free person the fine was 1,200 obols, while for the rape of a household slave the fine went from one to 24 obols, “depending on circumstances.” What strikes us today is not the particular notion of justice contained in the statutes, but the reverence with which they have been treated over such a great span of time, the beauty of the lettering, the continuous incorporation into new buildings as the old ones crumbled away. An early example, however unequal the laws, of that striving for order, for shelter from violence and chaos common to every human society. The form of the Odeon can still be made out: the semicircle of the amphitheater, some remains of benches, but most of it now is little more than broken stones. The Gortyn Code, however, is still intact, an abiding monument to the principle of legality. It is housed now in its own brick shelter, protected from the weather. Protected from people too—you can only look at it from a distance, through bars.

Having seen where the people we call Minoans lived, and formed some idea of their surroundings and the circumstances of their lives, the natural progression is to go on to see the things they made. Whatever reservations one has about the attractiveness of modern Iraklion, the city’s archaeological museum is one of the finest to be found anywhere, and its collection of Minoan artifacts quite unique. Here, beautifully displayed in room after room, are the objects that give physical expression to the spirit of that remote society, and trace the way that spirit developed and changed, from its beginnings in the Neolithic period ten thousand years ago to the high culture of the Palace period, between 2000 and 1450 B.C., and on to the time of invasion from the mainland and subsequent decline.

Among a huge variety of objects from all over Minoan Crete—Knossos, Malia, Festos, Tylissos, Zacros, Agia Triada, Gournia—are some that through the fame and mystery that surrounds them have become semi-legendary. Here is the Festos Disk, already mentioned, exquisite and baffling, printed on fresh clay three and a half thousand years ago, making it the first ever printed document. Here is the sarcophagus found in a tomb in the precincts of the palace at Agia Triada, its surface completely covered with painted plaster, depicting scenes of ritual worship and the cult of the dead. Once again we are in the toils of speculation. The jar the priestess is emptying, does it contain blood? What is the significance of the black bird that sits between two double axes, or the model ship that one man is holding out to another? Such things remind us that for all the patience we can muster and all the resources for research at our disposal, there is a world of values and beliefs forever beyond the reach of our understanding.

Then there is the celebrated ivory figurine of the bull leaper, caught in the very moment he is vaulting the bull’s foreparts, about to perform the astounding somersault which will land him on his feet again on the other side of the animal. The musculature and anatomical form of the body are rendered with what seems absolute fidelity until one sees that the arms and legs are longer than they should be—a device we meet with in contemporary art, revolutionary then, designed to convey the grace of the movement without loss of tension. His hair is made separately, of bronze threads. Priest, gladiator, devotee, slave, star athlete, what was he?

From the same period and the same place—the palace at Knossos—are two faience figures of snake goddesses, one slightly taller than the other so perhaps mother and daughter, both with prominent, naked breasts and elaborate skirts and coiled snakes wreathed around arms and body—the smaller also holds up rampant snakes, one in each hand. The snake was a principal object of worship among the Minoans, for whom it represented eternity, immortality, and reincarnation. The goddesses were fashioned for small household shrines and worshiped as domestic divinities, guardians of the house.

For many, the crowning glory of the museum is the room containing the Kamares ware dating back to the Old Palace period. This beautiful pottery owes its name to the Kamares cave in the eastern zone of Psiloritis, where a great quantity of it was discovered. A group of Italian archaeologists, in the 1890s, exploring caves in this wild and rugged terrain, stumbled upon a treasure trove of painted pottery, some fragmented, some virtually whole, bowls, cups, jugs, amphora, all of unique quality. This came at a time when almost nothing was known about the Minoans. They had not even been named yet, the work of excavation at Knossos had not yet properly begun. I have never read an account of this discovery, but I like to imagine that the magnitude of it came to them only gradually and with growing delight as they moved here and there in the recesses of the cavern, the light from their lamps falling on these heaps of pots, which had rested so long unseen and unappreciated, retaining their glowing colors in the dark of the cave.

Now we know what they at the time didn’t, that most of this pottery was fashioned in the palace workshops of Knossos and Festos. They superbly illustrate the Minoan feeling for dynamic movement based on interweaving patterns. The tentacles of an octopus, the shoots and tendrils of a plant, the fronds of a palm tree mingle with abstract curvilinear designs, spiral and coil and turn in on themselves, in a way that recalls yet again the stories of the labyrinth, that seemingly endless elaboration and extension of rooms in the palaces. Perhaps the maze, as idea and as design, was a fundamental element of Minoan sensibility.

So we wandered from room to room in this splendid museum, tracing the development of a culture, a search for form, which is a search also for meaning, through all the meanderings of taste and fashion. A strong religious feeling is expressed here, and a joy in natural forms and in the pleasures of the senses. There is no depiction of war. The Minoan people, throughout most of their history, enjoyed that sort of freedom from predators that allows animals or insects to flourish in certain habitats. The only way to attack Crete was by sea, and for that a strong navy was needed, but no one in the Mediterranean world of that time seems to have possessed such a navy—except the Cretans themselves. The Minoan kingdom was a thalassocracy, a sovereignty of the sea. They traded far and wide, they established colonies, they cleared the sea routes of pirates, but they fought no battles on their own soil, until the final ones that put an end to them.

It was a combination of circumstances that brought them down. Between 1500 and 1450 B.C. Crete suffered a succession of earthquakes which damaged the centers of power, weakening the island so that it became vulnerable to invasion just at the time when the power of Mycenae on the Greek mainland was expanding. The Mycenaeans were the first to occupy the island. When their day was over, it was the turn of Greek tribes from the north, with their sky god and their iron weapons. More primitive than those they conquered, they were unable to absorb or adapt what they found, or put anything in place of what they destroyed. It was the beginning of a dark age in the eastern Mediterranean that was to last for some centuries. The palaces were never rebuilt and never again inhabited, the invaders regarding them as uncanny, haunted places. Writing disappeared completely; what art was produced was crude and botched.

In the objects on display in the last rooms on the ground floor one feels this crushing of the spirit as an almost palpable presence, like an affliction, as if the collective mind of this gifted people had been stricken by the equivalent in cultural terms of Alzheimer’s disease. There is an increasing number of large, crudely molded terra-cotta figures of goddesses with rounded lumps for breasts and blind, coarsened faces. Their arms are raised in the conventional posture of prayer. Stand away a little and look at these groups, and they seem like creatures in mourning for their own ruin and for their ruined world, raising their arms in terrible mute grief.

On the floor above, however, lightness returns to the spirit. Here are the rooms devoted to Minoan wall paintings. Their qualities of gaiety and elegance and exuberant color are undeniable. More doubtful is the accuracy with which some of them have been reconstituted from the fragments of fresco, sometimes very scanty, that remained. Much dedicated scholarship has gone to reassembling these fragments, but also a considerable amount of dubious ingenuity and wishful thinking. Perhaps the most famous example of this, and among the most famous of all Minoan frescoes, is the “Prince with Lilies,” as he still continues, in spite of everything, to be called. Wasp-waisted, naked but for a loincloth, he wears a garland of lilies and a plumed crown, and he walks among flowers, holding an animal thought to be a griffin on a leash. Arthur Evans himself privately considered the fragments from which the prince was assembled to be quite unconnected, the head belonging to a king or god, the torso to an athlete of some kind, the rest of the body to someone else altogether. But who would be content with a barrowload of painted plaster chips when he could make a prince out of it? Evans succumbed, as sometimes before, to the desire to add luster to the world he had uncovered. The restorers, perhaps wanting to please him, on their own initiative painted over some parts to give an impression of unity to the assemblage.

The prince remained unquestioned for half a century, until 1960, when it was discovered, quite by accident, that the animal on the leash was not a griffin but a sphinx, and furthermore that it was the sphinx who should be wearing the plumed diadem, not the man at all. When faith is once disturbed, queries multiply. It began to be pointed out that the neck was joined to the torso at an extremely odd angle, that in terms of human anatomy the pose was impossible, that he could not be leading any kind of animal, whether legendary or real. More recently he has been declared to be not a prince at all but the god of eternal youth, flanked by two sphinxes, both crowned with plumed headdresses. But, others ask, if he is a god, why does he have the hairstyle normally depicted in Cretan art as belonging to a priestess?

And so it goes on. Clearly the representation as it stands is wrong in just about every way it could be. The only thing they got right was the lilies. This may not amount to fraud, but it is certainly a long-sustained deception. Does it really matter? In the course of the century since he was put together, the prince has taken on symbolic force. The fresco is a false image that exposure to millions of people has made true, embedded in popular imagination as the essential expression of Minoan elegance and vivacity of spirit. The original is still on display, among the most treasured possessions of the museum; and a copy still stands under the portico of the south entrance to the palace of Knossos where Evans placed it in 1901, a potent proof—if we needed another—of the power of the image to transcend objective categories of truth and falsehood.