CHAPTER SIX

PEACE AMID the CLAMOR

East of Iraklion lies the fourth province of Crete, Lasithi, with a high plateau at the heart of it and the sweep of Mirabello Bay as its open face, sheltered to the north by the headland of Agios Ioannis.

Mountain plains—like caves and gorges—are a special feature of Crete; the island numbers dozens or scores or hundreds, depending on the limits of dimension one sets on them. But the Lasithi Plateau is the biggest of them—the biggest flat area on the island. It forms a rough oval, rising to three thousand feet above sea level, eleven and a half square miles in area, entirely surrounded by higher mountains, dotted with thousands of stone windmills installed by the Venetians to irrigate the plain. These are picturesque with their cloth sails and they attract many visitors, but much of the work is done nowadays by gas-driven pumps. It is a fertile region, producing fruit and vegetables in abundance. Even if the windmills have mainly fallen into disuse, the plateau is worth the tortuous fifteen miles of road from Neapoli for the spectacular views, for the experience of an agrarian economy which is, taken acre for acre, one of the most productive anywhere to found.

The vast majority of visitors to the Lasithi Plateau come by bus and stay only for the middle hours of the day. The onslaught is heavy for such a small area, but by early evening almost everyone has left again, and the villages that surround the plateau continue the patterns of traditional life. The influx is contained and released, inhaled and exhaled, like breathing. The rhythms of local existence are disturbed, no doubt, but not much damaged. This is unfortunately not the case with some of the beach resorts to the north. The outskirts of Elounda, on the western side of Mirabello Bay, provide some of the worst examples on the island of the unbridled and haphazard building that has taken place in the rush to get in on the tourist boom.

Negotiating a succession of hairpin bends on the narrow road up to the hotel, we saw a car, victim of an accident, left at the roadside. There was always a damaged car in that same spot, all through the time of our stay there, but the truly alarming thing was that the cars kept changing. Taking this as evidence of frequent collisions on this road, we attempted to use a bus. There was a sort of agreement—or so we understood—between the hotel and the bus company that buses would stop near the hotel to pick up guests. But the drivers seemed unaware of this agreement and went sailing past, so we had to trudge back to the hotel and use the car after all.

This was a minor irritation. But we were both appalled by what had been done to the place itself. For years now an incessant, piecemeal building of vacation accommodations has been going on here, without regard to the rights of access to the coastal hillsides and the shore itself. A great deal of money has gone into this, both public and private, but very little has been invested in projects less immediately profitable, like communications, public transport, services generally. The roads, which are among the busiest in the region, are more or less what they always were, narrow, badly built, and badly surfaced, ever more fume-laden and dangerous. The lower roads, down toward the shore, have been so much encroached upon in the process of building that they are in places too narrow for cars to pass one another without complicated maneuvering, hemmed between the walls of the hotels that stretch ever farther up the hillsides, clambering up like competing plants in a forest, striving for star ratings, a view of the sea.

A dream sea. We had a piece of it to look at from our balcony, or from the poolside. But just try to get there. By and large, there is no way for people staying in these hotels or apartment blocks to explore the locality in which they find themselves. They certainly can’t walk anywhere, not with any pleasure. The roads are too harassing and too dangerous. And you can’t get off them because everything is staked out and fenced off.

The result of all this, locally around Elounda, as in other places on this north coast of Crete, is truncated hillsides partitioned off into lots, little tracts of noman’s-land awaiting the developer, the occasional acre or two of weeds and shrub, then perhaps a small olive grove that someone still clings to, fenced around with barbed wire. Dotted here and there are gaunt, unfinished buildings, roofless, the concrete framework a dark gray color, awaiting the owner’s next burst of prosperity to be converted into yet more vacation accommodations of one sort or another. This uniquely beautiful island, with its long history of human habitation, its landscape at once rugged and mild—the mingling that results from people living in harmony with their surroundings—has had substantial parts of its coastal regions stripped of sense and order in a matter of a few decades.

Not much point now in wondering what combination of greed, ignorance, lack of civic sense, and care for the environment could have led to this state of things. What has been missing is what is always missing, in Crete as in a thousand other places, cooperation between citizen and municipal authority, the ability of local communities, often traditionally poor, to withstand the invasion of capital and so take a longer view, retain some space for human purposes other than the single one of spending money, open the land to people instead of closing it. But this would mean admitting the inadmissible: that constant growth is a chimera, that the stream can dry up, that unlimited numbers of free-spending people cannot be accommodated in a limited space, and that continued attempts to do it will foul up the very thing that the people came for in the first place.

These gloomy thoughts gathered in us but were then dispersed again, dispelled by the sheer, inalienable beauty of the island, which is still, despite all such brutalizing, the truth of it. There is the light, first and foremost. Even the ravaged hillsides of Elounda can seem healed and restored by the benediction of Cretan sunlight. At the changing of the seasons, spring into summer and summer into autumn, there are days of quick transition from overcast skies to periods of clear weather, with extraordinary effects of contrast in the quality of vision. The haze shifts and for some moments everything is seen in a shaft of brilliant light, every slightest gradation of color in the sea, every detail of the horizon, all clear to the point of hallucination. Looking east from Elounda you see the small island of Psira, far out in the bay, suddenly distinct as if someone had snatched away a veil from it, while the headland of Mohlos beyond is still shrouded in a pale violet haze, only just discernible, with the most tenuous of dividing lines between sea and landmass and sky. In this weather the moon goes through spectral changes, at first dark red as it clears the cliffs, then gold, then white as it climbs free of the haze.

And then there is the abiding fact that a little effort will take you clear of crowds into places where you can feel the spell of solitude. A journey of three miles north from the clutter of Elounda, following the coast road toward the tip of the Agios Ioannis headland, brings you to the tranquil resort of Plaka, with its pebbled beach, translucent sea, and tavernas fronting the shore, with fresh fish on offer. Quitting the road and taking the track that leads farther north along the hillside, just above the sea, we found ourselves after ten minutes quite alone. We also found ourselves embarked on a very memorable walk.

No habitations here, no cars—and on the day we did this walk no people, except a young Finnish couple who were setting out along the track as we returned. It is very rare to find a Cretan walking for pleasure. It seems to them a meaningless and redundant activity, perhaps even slightly mad.

The only sounds on this summer day were birdsong and, at first, distant voices from across the water, where boatloads of people were landing on the island fortress of Spinalonga, just beyond the humped promontory below us, which bears the same name. This small island has had a checkered and in some ways chilling history, though it has also been the scene of a moving and courageous human enterprise practically without parallel elsewhere.

The Venetians had already been masters of Crete for more than three hundred years when they decided to fortify the island to guard the approaches to the western side of the gulf and the sheltered anchorages south of the promontory. The remains of the fortress they built are extensive and well preserved, though much overgrown and hazardous to explore. The high walls on the north side, with their crenellations and escarpments—clearly visible to us from the track we were following high above—are cunningly incorporated into the granite of which the island is made. The whole construction is an astonishing feat of engineering. The island was virtually impregnable, and even after the Turkish conquest of Crete in 1669 it did not fall into their hands for another half century—not until 1715. And even then it was not taken by force but ceded by treaty.

Starting with the few Ottoman troops left as a garrison, the population grew until by the end of the nineteenth century more than a thousand families of Turkish descent were living on the island, all of them devoted to the thriving local industry of smuggling. This was so lucrative that even after 1898, when Crete was declared autonomous, the Turks of Spinalonga refused to leave their homes. In 1903, however, they fled en masse when the Cretan Republic under Prince George decided to make the island a leper colony. The story of this colony has been well related by Beryl Darby, and I am indebted to her for many of the details that follow.

Leprosy was still at that time one of the most feared of human diseases, because of its contagiousness, the terrible disfigurements it brought about, the progressive degeneration of the body that accompanied it. And because it was so feared, those who suffered from it were treated as outcasts. Several hundred lepers, men and women, were taken from the caves and shacks where they had been living, all over Crete, and brought here. In these early years, isolated on the island, they were in desperate straits, neglected and abandoned, often in great pain, obliged to fend for themselves without medical attention or regular supplies of food and fresh water, unable to treat the suppurating wounds which are characteristic of the disease. All looked peaceful below us that day: the glittering expanse of the bay, the ferries plying across from Agios Nikolaos and Elounda. But if that little island could voice its own past, the voice would come as a single cry of suffering.

As the century advanced, things got better. A new contingent of lepers was sent to Spinalonga from Athens, people on the whole better educated, less resigned—they numbered lawyers and teachers among them. With the help of the lepers already there, they struggled to establish a community, repairing the dilapidated houses vacated by the Turks, quarrying their own stone to do it. They constructed cisterns to collect rainwater and used the open fireplaces in the old Turkish laundry to heat the water so they could keep their sores clean. They printed their own newspaper, with news of various events on the island. They even built a theater and put on plays. Above all, they assumed responsibility for one another, the stronger attending to the weaker, making sure that no one died alone. It is a story of courage and cooperation under the most terrible conditions and should have pride of place in the annals of heroism.

The last lepers on Spinalonga—the thirty still alive—were transferred to mainland hospitals in 1957. It is a strange experience now to walk about on the island among the decaying houses of the lepers and the scattered ruins of the fort, where the garrisons of the conquerors and the community of the sick once lived and died. This is only a ghost town, with rotting timbers and listing walls and hanging shutters. Some signs of those former lives still remain. The lepers’ disinfection room and dispensary are still there, and there are some marks of domestic life: an old basket on a shelf, a tilted cupboard with doors hanging open, a bank of red geraniums growing over a doorway.

The track ascended, Spinalonga was left behind, the bay of Mirabello opened before us, with the mountainous headlands one beyond the other, stretching away east toward Sitia. On the landward side, the hills rose steeply, marked by the dark green of the carob trees, with their lighter clustering pods, and flowering phrygana plants in domed clumps and granite outcrops weathered here and there to a warm red-brown. The mid-morning sun brought out waves of scent, at times almost dizzying, from the aromatic scrub all around us. One can range at will in the Cretan maquis—no venomous snakes lurk here, or anywhere else on the island, which is a very agreeable piece of knowledge for the walker, who has enough to do avoiding the spiny plants that grow everywhere. It seems that there never have been fanged snakes on Crete. Their absence, typically enough, has been explained by stories. In antiquity Herakles was said to have banished them; later this feat was attributed to St. Paul the Apostle, who was bitten by a snake—on Crete, the Cretans say, wanting their island to be the scene of everything, even of disasters; but it was on Malta that it seems to have happened.

Perhaps to make up for this deficiency in the element of danger, a body of folklore has grown up around a lizard of snakelike appearance called liakoni, which, though entirely harmless, is still commonly believed by the country people to have a life-threatening bite. In fact, the only really dangerous customer on the island is the Mediterranean black widow spider, recognizable by its black and hairy abdomen, a piece of information I owe to the excellent Natural History Museum of Iraklion. I have never encountered this spider in the flesh, and I hope this lack of acquaintance will long continue.

We walked on and the solitude settled around us. This, in its peace and tranquility, in the heat-hazed shapes of mountains across the bay and the melting line of the horizon where sea meets sky with a blue that belongs to neither, this is among the most beautiful places our Earth has to show. We found ourselves fervently hoping that it would be left alone for anyone to enjoy, that people were not sitting in some office at that very moment, making dire plans to develop it.

The light is so extraordinary—one keeps coming back to that. It is soft and radiant yet at the same time relentlessly clear. Cretans on the whole, like their compatriots on the mainland, have not been much given to folktales of the darker sort, those featuring threatened children and ambiguous adults liable to change masks. The light here is too clear and bold for such a tradition to develop. You need the more diffused light and more enveloping shadow of northern latitudes for that. There is in Crete, of course, as all over Greece, a prevalent belief in the evil eye, and this is certainly an ambiguous matter, because anyone can have it and exercise it without in the least being aware, conscious of nothing but goodwill. On the other hand, there are those believed to possess this power and to use it malignantly and in secret. At least until recently—and perhaps still today—it was not uncommon for the village priest to be called in to expel demonic presences and purify the house. Blue beads are often used as talismans, worn about the person or hung up in a car, to ward off evil influences of this kind. Sometimes, when people have misfortunes not easy to explain in the natural course of events, they carry out tests to try to determine whether the evil eye is at work. Once I was present at such a test. It consisted of adding drops of olive oil to a glass of water: If the oil floated, which of course it should normally do, all was well; if it mingled with the water, demons were at work. This time, to everyone’s relief, the oil conformed to the laws of its nature and floated. On another occasion I was suspected of having the evil eye myself. I was giving a hand with harvesting the grapes in the vineyard of some neighbors. It started to rain in the middle of the morning and went on for two or three hours—a very unusual event for the time of year. Grapes should never be harvested wet; the skins break too easily and there is danger of mold. I was the newcomer, the stranger. It was obvious that I had brought bad luck, and behind bad luck is always the possibility of the evil eye. I was asked, politely but with unmistakable firmness, not to offer my services the next day. And sure enough, the next day it didn’t rain.

We kept to the track, gradually climbing, following the curving line of the hillside, with the shimmering expanse of the water below, coming eventually to the narrow tip of the promontory. Here, fitting end to such a walk, lest there should be danger of beauty saturation, a huge fence barred the way, sixteen feet high at least, surmounted by six rows of barbed wire and an enormous circular sign that read: STOP. Only the military can make their meaning as crystal clear as this. From here, if you could get through, you would find yourself looking out toward the Sporades, with Turkey, the traditional foe, beyond.

The track continued around the headland, leading to the road that runs south again toward the village of Vrouhas. But we wanted those views again and so retraced our steps. Coming from this side we noticed what we had missed before: At roughly the halfway mark was a cave above the track, the entrance walled very carefully with close-fitting stones to a height of about five feet. The wall blocked the entrance completely—there was no way in without climbing over it. Inside was a flat area, just enough space for a man to stretch out.

Caves are always a mystery. Who had laid stone on stone to build this wall, now peacefully colonized by purple campanula growing along its base? Fugitive, hermit, guerilla? Xan Fielding, who had more firsthand experience of Cretan caves than most, having fought in the White Mountains with the Resistance during the years of German occupation, relates a story that perfectly illustrates the Cretan desire to appropriate the past, to be the source of things, to blend myth and history into a possession as real and solid as the stones of their island.

While Fielding was sheltering in a cave near Souyia in 1942, a local man told him that the cave he was inhabiting was the very one in which the Cyclops Polyphemus once lived and kept his flocks. The Cyclops were a savage race of one-eyed giants who lived by tending sheep. Homer tells the story of how Odysseus and his companions, returning from Troy, took shelter in the cave of Polyphemus, who, finding them there, began systematically to eat them. He had already devoured six when they disabled him by driving a fire-hardened stake into his single eye while he lay sleeping. The blinded giant pushed aside the huge stone that blocked the entrance and kept his sheep penned in the cave. He tried to fumble for his enemies as they went through, but they clung to the fleecy undersides of the sheep and so got free. Once embarked again, Odysseus could not resist taunting his outwitted enemy. The enraged Polyphemus cast down great rocks in the direction of the voice, almost succeeding in crushing Odysseus’s ship. The giant’s prayers for vengeance to his father Poseidon roused the sea god’s wrath against Odysseus and cost the hero ten years of troubles and dangers before he could return to his native Ithaka and his faithful Queen Penelope.

It happened here, Fielding’s Cretan friend insisted, this was the cave. And to prove it he pointed out two rocks in the sea below. Those were the stones that the stricken monster hurled down. The commonly accepted view, which sets the scene off the Sicilian coast near Catania, was quite mistaken. The story belonged to Crete and it had been stolen from her.

This stubborn sense of possession is not surprising when one considers Crete’s history. Foreign masters, alien religions, these were the Cretans’ familiar circumstances for many hundreds of years, and the refusal to submit, the frequent uprisings, cost the people untold bloodshed and suffering. In these circumstances, whatever can serve to maintain the spirit and sense of identity must be seized upon and asserted. In Cretan folk song, and especially the rizitika, the mountain songs that began to appear in the eighteenth century during the darkest days of the Turkish occupation, two themes occur again and again: the beauty of the island and the indomitable spirit of its people. This is entirely to be expected. If you are called upon to suffer in defense of something, whether a land or ideal—and in this case it was both—it is natural to stress the desirability of what you are defending and the courage needed to defend it.

There have been other by-products of occupation. The Cretans, like the Greeks generally, have always been characterized by an inability to combine together and present a common front. Never was that saying of Terence truer of any people: “So many men, so many opinions: each a law unto himself.” The spirit of resistance, even to a common enemy, and the harshness of the struggle, instead of uniting the people, seems to have led to that fierce kind of individualism and independence that lays stress on narrowly local loyalties.

Then there is what seems to many foreign observers the strongly materialistic view of life that most Cretans take. If you see a group of men in earnest conversation in a bar, they are quite likely to be talking about the cost of living. Any vague and unfounded rumor of a bread shortage on the way can result in panic buying and hoarding on a large scale. This is not the kind of consumerism that characterizes more prosperous societies in the West; it is more like a fear of want, of being left unprotected. Generalizations are dangerous, we all know that, but it doesn’t seem too fanciful to set this down, at least to a considerable extent, to the insecurities of countless former generations still working in the psyche of the people.

These were the thoughts set in train by that meticulously walled cave that we saw on our way back to Plaka. We never succeeded in finding out anything more about this, either because those we asked didn’t know, or because my Greek was not really up to it….

Principal town on the Bay of Mirabello, and capital of the province of Lasithi, is Agios Nikolaos, which has a cosmopolitan feel, reflected in the bars and restaurants and in the general style of life—it probably has the highest concentration of resident expatriates anywhere in Crete. The setting is striking: The town is built on a small peninsula around a lake of darkly shining water, described as bottomless in the tourist literature and even on street signs. Certainly it is very deep—seventy-five feet, I was told, at the deepest point. The lake has an outlet to the sea and so forms an inner harbor. Some of the lakeside restaurants are excellent, more sophisticated and offering a wider choice than is general on the island, with very good pasta dishes on the menu and imaginative salads and specialties like grilled swordfish or zucchini flowers fried in an egg batter, accompanied by the light, dry Cretan wines, so much pleasanter—to my taste, at least—than the resinated wine called retsina, common on the Greek mainland. Cretan red wines have always been well thought of by visitors and inhabitants alike, but the white have improved very considerably in the last ten years or so, especially those from the region of Sitia.

The town beaches can scarcely be called beaches at all, but we found a good one at Almiros, just a little over a mile to the south. Farther around the bay, in the area of Kalo Chorio, they get better and better. My own favorite is Istro, which has pleasant tavernas and some excellent sandy beaches; in places they have even spared the trees lying back from the shore. From here, I think better than anywhere else on the island, you can enjoy the combined beach and sight-seeing holiday that brings so many people to Crete. For those who like walking, tracks in the hills behind afford splendid views over the bay. Knossos is not far away, perhaps an hour by road. Nearer at hand is Gournia, another Minoan palace site, spectacularly situated on a saddle between two peaks, from where it once controlled the isthmus between the north and south coasts, no more than twelve miles at this narrowest point.

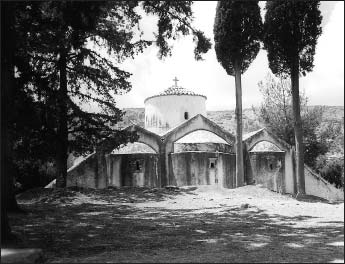

The Church of Panagia Kira near the village of Kritsa, a little way inland from Istro, is one of the loveliest of Byzantine churches and one of the oldest, with the most complete set of frescoes to be found on Crete, painted at different times in the island’s history and thus affording a unique opportunity to trace the developing styles of Cretan fresco painting through the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. Among a number of paintings of outstanding quality and interest is a tremendous Last Supper in the center, and in the southern aisle vivid scenes of Christ’s Second Coming, including representations of the Day of Judgment and the Punishment of the Damned. On the northwestern pillar is a portrayal of St. Francis of Assisi—a very rare instance of a Western saint in an Orthodox church, perhaps the result of Venetian influence. Crete is well endowed with churches, many of them beautifully situated and full of interest; but if obliged to choose among them, to single out one which best exemplifies the atmosphere and the spirit of devotion of medieval Byzantium, I would favor the Panagia Kira.

The Church of Panagia Kira, near Kritsa

The days were running out now, they had gone quickly. We had started wondering—always a sign that a trip is coming to an end—how things were at home, whether our vines and olives were prospering, whether there had been enough rain. We would have the grass to cut and the aphids to deal with and the vegetable garden to clear of weeds. We would have to secure the forgiveness of our five cats for having stayed away so long….

There was still so much left to see. We decided to continue south across the neck of the isthmus to Ierapetra, which is the largest town on the south coast, the hottest and driest town on the island, and the southernmost town in Europe. But our desire to go there didn’t stem so much from statistics, though these do in a way affect one’s attitude to places. We had talked ourselves into a valedictory mood, and it seemed somehow fitting to end our trip in the region where the last descendents of the Minoan people, whose history of power and decline had so absorbed us as we went from room to room in the Iraklion museum, met their end. They are known as Eteocretans, or “true Cretans,” people of the original, pre-Greek stock. They had been driven to this remote eastern region of the island, where they preserved themselves for some centuries in their fortified city of Presos, still clinging to their language and traditional mode of life. They were finally defeated in 146 B.C. by the Dorians of Ierapetra. Those who were not killed or sold into the slavery were scattered and ceased to be a separate component of the population. Their city was razed to the ground. Thus ended what has been called the thousand-year twilight of Minoan civilizations.

Of ancient Presos little remains now—it was never rebuilt. Present-day Ierapetra is a prosperous town with a handsome waterfront and a very good beach. May was advanced, we were about to return to landlocked Umbria, so we ventured in for a swim. The water was chilly, but—as people say when they are glad to get out again—invigorating.

By this time we were both feeling hungry, but we wanted to have our lunch somewhere quiet—Ierapetra seemed too busy and townish. We got into the car again and headed westward. The road keeps close to the coast for seven or eight miles, then turns sharply inland. Just below where this change of direction occurs is the village of Mirtos, an altogether captivating seaside resort with the tremendous advantage of being at the end of a turnoff from the main road, which passes well above it, so there is a blessed absence of traffic, creating an air of leisure and tranquility that is increasingly rare in Cretan coastal resorts. There was a long, curving shingle beach and a promenade running close to the water, lined with bars and tavernas. The houses were whitewashed and scrupulously clean and neat. There were no very old-looking buildings anywhere in evidence, also unusual but not surprising in view of what we had read of the wartime history of the village: Mirtos was destroyed by the Germans in 1943 in reprisal for resistance activities. The job was done thoroughly; it seems they hardly left one stone on top of another. But Mirtos, unlike the last refuge of the Eteocretans, was rebuilt.

Tastes differ, in places as in most other things; and as we know, it is useless to argue about them. Often enough it is what the place stands for as much as what it is in itself that draws our regard or rouses our affection. I took to Mirtos immediately, not only because it is peaceful and pretty—there are still quite a lot of places on the island that fit this description—but because it has been terribly mistreated in the past, and yet has restored and renewed itself. And so it comes to represent what I feel about the history and the spirit of Crete as a whole.

At Mirtos, sitting at an outside table of the Votsalo tavern, with the sea just below and a warm breeze wafting over from Africa, glasses of the excellent Greek Mythos beer at our elbows and the resident cats showing great interest in our mutton chops, we had to start thinking about getting back to Iraklion and then home to Italy. The trip had been a success for both of us, in slightly different ways. For Aira, seeing the island for the first time and adding it to her list of places to see again. And for me, seeing it again and finding it essentially as I remembered. To leave them always with regret is the gift some places—not so many—make us. It’s the gift life itself makes us, if we are lucky.