One Christmas Day at the Middleton Theater in the late 1980s, Alex set himself on fire while sitting behind the concession counter. Sea of Love was showing that day, and Alex’s sweater caught fire on the 1950s’ electric-coil space heater he brushed up against. He didn’t notice the added heat of the flames, but fortunately the manager yelled from the ticket booth, “You’re on fire!” Being more or less quick of mind, Alex remembered what he had been taught as a child. He dropped and rolled around on the floor, which was caked with yellow peanut oil, until the fire was extinguished. Once the cheering customers were safely seated, the manager and Alex resumed staring at the same wall, letting the muffled voice of Al Pacino pass through.

Having shown Sea of Love for the last few weeks, Alex and his manager knew exactly what to expect from the movie. But this did not prepare them for Alex’s sweater catching fire. As we saw in chapter 5, Bayesian inference is great for predicting the predictable. It works in slow-changing or cyclic environments, or when we can create a logical hypothesis about causality. Humans do it instinctually. Jet lag, for instance, is the reestablishing of the circadian rhythm in the brain in a new time zone.

As we’ve seen, our brains collect shortwave data on behavioral patterns every day. In Bayesian terms, we continually update our “priors,” which we codify as cultural norms. This means we won’t be surprised that a study of millions of Tweets, as reported in a leading science journal, revealed that people are both happier and tend to wake up later on weekends. As Bayesian thinkers, we already expect this from the workweek, or in Bayesian speak, our priors are hardly updated by the findings. The Twitter analysis, however, gives a future algorithm the same baseline about collective behavior, except at a scale that no individual person could perceive. With this baseline, you can identify anomalies.

Using vast amounts of Twitter and other media content, Nello Cristianini and his group at Bristol University monitored fluctuations in the public mood following specific events, such as economic spending cuts or Brexit. They also monitored seasonal variations in the public mood. They found that especially in the winter months, mental health queries on Wikipedia tend to follow periods of negative advertising. As Cristianini said, people tend to respond to their findings with “That’s it? We already knew that!” That’s fine with him, as his goal was to quantify human collective behavior rhythms.

Many of these rhythms carry on largely as they have for hundreds or thousands of years. In trying to define what has changed, it helps to consider two “shapes” of cultural transmission: vertical and horizontal. The results of these transmission types are what archaeologists call traditions and horizons. Traditions reach back in a deep and narrow fashion, through many generations of related people, usually residing over relatively small areas. Horizons are shallow and broad and can cover magnitudes more people over a much larger region. Today, because of online media, horizons can easily reach around the world. Sometimes a strand within a tradition can suddenly erupt into a horizon—like in 1976, when Walter Murphy’s disco version of Beethoven’s Symphony no. 5 in C minor spent one week atop the pop charts. The horizon usually flames out rather quickly, and the tradition reasserts itself. Few people, for example, remember Murphy’s “A Fifth of Beethoven.” A correction was made, the horizon disappeared, and the tradition carried on.

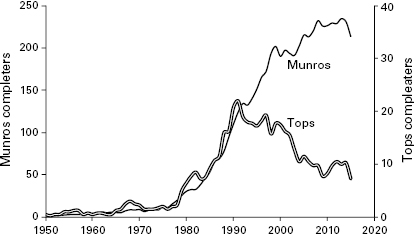

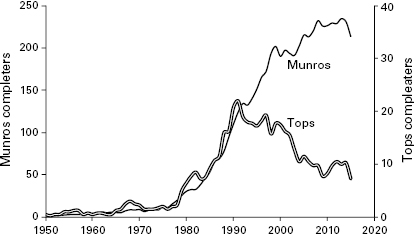

Let’s quantify all this with a rather obscure illustration. In the highlands of Scotland, there is a long-standing tradition of climbing a group of misty hills known as the Munros. There are some 280 of these hills, all over three thousand feet, and for generations people have set out to “compleat” the list by walking up every one of them. These compleatists proudly join the list maintained by the Scottish Mountaineering Council. The cumulative number of compleatists keeps growing steadily—a tradition that consistently adds about two hundred climbers per year. Within this tradition, though, there was a bit of a fad—a horizon—called the Munro Tops, a different group of slippery Scottish hills that tend to be miles from the nearest road, so that a fall might leave you crumpled and alone, writhing in an expanse of soggy peat. During the 1980s and 1990s, the Munro Tops fad rose and fell, as you can see in the figure, while the main tradition of the Munros keeps plugging along steadily, year after year.

With this sketch of traditions and horizons along with how they differ, let’s explore in depth a few more examples of longer-lived horizons that have arisen from deep, traditional behaviors around the world, starting with diet and then moving to gender relations and charitable giving.

Often as resilient as languages, dietary traditions tend to move with migrations, because they are learned in families and are part of group identity. About a thousand years ago on the Comoros Islands, for instance, a few hundred miles off the coast of Mozambique, Austronesian colonists from six thousand miles to the northeast not only brought their native diet of mung beans and Asian rice but also then maintained those preferences for centuries across a “culinary frontier” from African mainlanders who cultivated millet and sorghum.

This might sound as if a tradition is becoming a horizon as a result of population movement, but it isn’t. Just because people move, sometimes over considerable distances, they can still maintain distinctive food traditions for generations, even when they live near other groups and intermarry. For example, after Hurricane Katrina in 2005, a quarter-million New Orleans residents moved to Houston. Soon after, Andouille sausage, a Louisiana creole staple, began appearing in markets all over the city. Houston saw the same thing earlier with a tremendous influx of Vietnamese refugees, who brought with them their native customs and foods.

Those are some dietary traditions, but into the deep diversity of dietary traditions around the world, one product—sugar—is bulldozing a new horizon. For millennia, cultivating sugarcane was a tradition, after it was first domesticated in New Guinea about eight thousand years ago. Some thirty-five hundred years ago, sugarcane spread with Austronesian seafarers into the Pacific and Indian Oceans. Sugar was first refined in India, and then in China, Persia, and the Mediterranean by the thirteenth century. By the fifteenth century, Portuguese merchants had established large-scale refineries on the island of Madeira. Christopher Columbus married the daughter of a Madeira sugar merchant, and by the seventeenth century, profits from selling refined sugar in Europe drove the slave trade and its plantation economy in the Caribbean and Brazil.

In England, the sugar business took off in Bristol, London, and Liverpool. By the mid-1800s, the leading sugar companies were refining thousands of tons of sugar per week. As Bristol engaged with the West Indian sugar trade by the early seventeenth century, slavery was so integral to the trade that after Britain abolished slavery in 1833, the Bristol city council paid £158,000 (about $20 million today) to Bristol slave owners as compensation. Today, the legacy of those profits is quietly visible in stately sandstone mansions—formerly household-scale sugar refineries—and the Tate Britain museum in London, as Henry Tate made his fortune in sugar refining.

What has happened since qualifies as a horizon in dietary change. Westerners now get about 15 percent of their total calories from sugar, which in the form of cane and beets is the world’s seventh-ranked crop by cultivated land area. Just three hundred years ago, sugar was not a major caloric component of anyone’s diet. Dietary change on this scale has never happened so fast. The last comparable change in human carbohydrate consumption was the transition to dairy products during the Neolithic, but it occurred over millennia. This was long enough for natural selection to spread the gene for lactose tolerance among early dairying populations. In the relatively short time in which refined sugar invaded diets, however, the human body has had no such adaptation. Refined sugar can be as toxic as alcohol. After drinking a can of cola, injecting ten teaspoons of sugar into your system, the pancreas (hopefully) pumps insulin to get the liver to convert your spiking blood glucose into glycogen.

Markets for refined sugar are driving the rapid growth in type 2 diabetes and coronary heart disease, as seen in countries around the world, where each rise in sugar consumption statistically leads to a rise in obesity rates. Americans have doubled their insulin release in twenty-five years. In 1990, about 11 percent of a typical US state population was obese, and no state had higher than 15 percent obesity. By 2014, statewide obesity rates had nearly tripled, and no state was below 20 percent in terms of obesity.

Something else happened in 1990: obesity and median household income started to correlate inversely. This meant that poorer households on average showed higher obesity rates than wealthier ones. Starting from no significant correlation in 1990, the correlation grew steadily year by year. By 2015, the correlation was stronger than ever. In states where the annual median household income was below $45,000 per year, such as Alabama, Mississippi, and West Virginia, over 35 percent of the population was obese, whereas obesity was less than 25 percent of state populations where median incomes were above $65,000, such as in Colorado, Massachusetts, and California.

Although this qualifies as a horizon, refined sugar has, ironically, become a tradition among the poor. “I was nine months old the first time Mamaw saw my mother put Pepsi in my bottle,” wrote J. D. Vance, who is from Jackson, Kentucky, in his book Hillbilly Elegy. Vance, whose poor grandparents moved from Jackson to a steel town in Ohio, describes the traditions of Scotch Irish Americans, underpinned by generations of poverty, from the sharecroppers to the coal miners, to factory workers, to the now unemployed. Besides traditions of group loyalty, family, religion, and nationalism, the Scotch Irish of Appalachia also inherited pessimism and a dislike of outsiders. “We pass that isolation down to our children,” explained Vance.

Let’s move from sugar tolerance to cultural tolerance. It may seem the world has grown more intolerant, with highly politicized social media groups trashing each other and coming up with increasingly irrational conspiracy theories, but as Harvard political scientist Nancy Rosenblum argued, everyday neighbors, in the real world, are still tolerant and cooperative. Political scientists have a theory that whereas the Industrial Revolution disrupted traditional value systems, the postindustrial world is moving toward rational, tolerant, trusting cultural values. As Damian Ruck, a researcher at the Hobby School of Public Policy in Houston, has found, the World Values Survey over the last twenty-five years documents this. Conducted at five-year intervals for over a quarter century, the survey is a remarkable project: lengthy native-language interviews of a thousand people in every accessible country on earth, covering everything from religion to family, civic responsibility and tolerance of others. Among all these values, Ruck discovered that tolerance of others had changed the most, and for the better, over the past twenty-five years.

One dramatic example has been the rapid decline of female genital modification (FGM) in central and eastern Africa. Just a decade ago, nine in ten women in most of central and east Africa—100 million women—had undergone FGM. The tradition has long invoked a cultural perception that natural female physiology is shameful. Women who have undergone FGM as girls frequently must be operated on again to allow childbirth and even permit sexual intercourse. By 2015, the practice had dramatically declined in Kenya: among Kalenjin women, only one in ten under nineteen, compared with nine in ten over forty-five, had undergone FGM. But this horizon is not uniform: FGM is still above 85 percent in Guinea, Egypt, and Eritrea. It declined rapidly in southern Liberia but not northern Liberia.

According to another theory, this global transition—toward self-expression, tolerance of diversity, secularization, and gender equality—is driven by the global decline in marriage and fertility rates. Since 1950, the total fertility rate has declined from 5 percent to about 2.5 percent globally. Marriage is declining even more rapidly. In India, arranged marriage, which has predominated probably since the rise of Hinduism in the fifth century BC, has declined from over half of all Indian marriages in 1970 to only a quarter in 2016. In the United States, despite more ways of getting married and with more government tax breaks, marriage rates have sunk since the mid-twentieth century. By 1960, two-thirds of the “silent generation” was married, but by 1980, it was only half of baby boomers, and by 1997, only a third of Gen Xers. By 2015, only a quarter of millennials was married, and the Pew Research Center even predicted that one-quarter of millennials may never get married.

The fluidity of marriage rates though time and correlation with economics makes it doubtful that humans are “hardwired” for monogamy. Thinking back to the last chapter, perhaps marriage is a cultural adaptation rather than an innate human universal, which has persisted like a large set of branches on a phylogenetic tree with a common root. One theory is that monogamous marriages became widespread during the Neolithic, helping people survive the new threat of sexually transmitted diseases. In fact, the oldest nuclear families identified by archaeology are from the Neolithic. In chapter 2, we described the grisly human skeletal remains of a village raid around 5000 BC. Those remains also revealed a small group whose distinctive isotopes indicated they were from a different village: an elderly female, a man, a woman, and two children. The man was probably the father of the two children, who inherited certain features of his teeth. Was this a nuclear family, with grandma included? Quite possibly; at a nearby site in Germany, two Neolithic parents were buried embracing their children, according to ancient DNA and isotopic analysis of their remains.

If monogamy and nuclear families, never universal among the world’s societies, arose as adaptive cultural traditions, they have since needed to be actively maintained. In Europe, where patriliny is thousands of years old, extra-pair paternity (cheating) has averaged only about 1 to 2 percent per generation during the last four hundred years, according to a study of Y chromosomal data. Similarly, genetic tests in Mali showed extra-pair paternity rates of only 1 to 3 percent among the Dogon. For Dogon women, who viewed menstrual blood as dangerous and polluting, monogamy was ensured by monthly seclusion inside an isolated menstrual hut for several uncomfortable nights. After a woman gave birth, she had to revisit the menstrual hut, and the husband’s patrilineage made sure that she slept only with the husband.

The economy of marriages offers explanation for change. Looking through the 2002 census of Uganda, evolutionary anthropologists Thomas Pollet and Daniel Nettle found a supply-and-demand effect: polygynous marriages were more common in districts where women outnumbered men. They also found that polygynously married men owned more land than monogamous ones. In agrarian and pastoralist societies, more land means families need more children as sources of free labor, and children are viewed as wealth.

Fertility is declining, though, in wealthy developed societies, where family economics have been reversed. In a knowledge economy, fewer children mean more wealth to invest in their education. In an age when four years of college costs as much as a house, and many top jobs require further graduate training, the economic choice may be for no children at all. The “DINK” bumper sticker on that Mercedes SL passing you at eighty-five miles per hour sums it up: “Dual Income, No Kids.” Compare the household economics of two generations—millennials on short-term contracts, living with parents in dormitory-style complexes, versus baby boomers with long-term jobs and houses that have increased in value twentyfold since the 1970s—and the decline in marriage rates makes sense.

Another trend associated with millennials—however unfairly—is slacktivism, a term used by international charities that refers to the facile online support of a trendy cause. Of the million or so Facebook users who “liked” the “Save Darfur” campaign of 2010, for example, over 99 percent made no monetary donation. Some fear that slacktivism threatens the long tradition of sustained charitable giving. They may see a tipping point in 2014, when people posted videos of having a bucket of ice water dumped on their heads in the #IceBucketChallenge (IBC) to support the fight against amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS, or Lou Gehrig’s disease). While Charlie Sheen emptied a bucket of money on himself, and a YouTube minister claimed the IBC covertly referenced the Antichrist of the Book of Revelation, regular people donated, often online or from smartphones. Like the Munro Tops we talked about earlier, or the charitable giving after a well-publicized natural disaster, the timeline of IBC donations was a massive burst of giving that waned in a matter of months.

The IBC was immensely successful, ultimately raising over $200 million for the ALS Association—so much money, in fact, that the IBC in effect funded the scientific discovery of a gene that contributes to ALS, with a 2016 paper in Nature Genetics thanking the IBC. If the IBC were to become the new paradigm, however, it would pose a challenge: the philanthropist John D. Rockefeller wanted sustained engagement from contributors, who should “become personally concerned” and be counted on for “their watchful interest and cooperation.” Rockefeller aimed to establish a charitable tradition. Yet the IBC motivates a horizon model, wherein charities have to continually dream up new, one-off campaigns that quickly spread as a shared trend rather than as a tradition.

Still, it sounds easy enough, so why doesn’t it work? IBC spin-off efforts, for example—such as the Mice Bucket Challenge (mouse-shaped toys being dropped onto cats) for animal shelters—were not nearly as successful. In contrast to sustained, traditional giving that is learned across generations, the IBC model might normalize long droughts of funding between large bursts of giving.

Meanwhile, long-running charitable traditions appear as resilient as ever. We can thank millennials, who are no slacktivists; teenage volunteerism in the United States has doubled since 1989. The tens of thousands of family foundations in North America, triple the number in 1980, collectively hold hundreds of billions of dollars in total assets, give tens of billions to charity each year, and are so traditional that they gave only 4 percent less in the year after the financial crash of 2008. The tradition exists outside the foundations as well. By 2015, Americans gave $359 billion—over $1,000 per capita. Even adjusted for inflation, charitable giving has roughly tripled since the late 1960s. The traditional nature of US charity appears also in consistent giving in distinct categories. For at least fifty years, as far back as detailed records extend, religion has been the leading charitable-giving category by a wide margin.

Religion, of course, is the granddaddy of traditions. Despite claims to the contrary, religious traditions abide. Using data from the World Values Survey, Ruck detected only a slow, almost-insignificant decrease in “religiosity” over the past quarter century. Although education may overtake religion as the largest giving category in some future decade, each major category of US charity has grown over the past half century. It is multiplicative growth, where the rich get richer: the more that religious and educational organizations get one year, the more they receive the next year. Unlike horizons, traditions do not go quietly.

It looks as if Rockefeller was right, but there is one catch. Traditions are handed down through people we know or trust, but we might lose trust in these figures, lose our interest in them, or even lose our ability to know who they are. The phenomenon of fake news comes to mind, which we’ll discuss later, but another illustration is the university protests around the United States during the academic year 2015–2016. As a result, certain older alumni withheld (considerable) donations to their alma maters, believing that identity politics were getting in the way of solid education. Feeling “dismissed as an old, white bigot,” a seventy-seven-year old alumnus of Amherst College stopped his usual donations. In fall 2015, while Mike was dean of arts and science at the University of Missouri, some of the top donors told him they were pulling the plug on their contributions following increasingly nasty student protests, a faculty member slugging a student and not being fired for it (she eventually was), a walkout by the football team a couple days before a nationally televised game, a sudden spike in political correctness, and what alums saw as the coddling of students. On the East Coast, a wealthy Yale alumnus reconsidered his regular (sizable) gift after seeing the viral video of a student yelling at her residential college head, who, with his wife, eventually stepped down from their roles as “house parents.” That Yale professor happened to be Nicholas Christakis, a network scientist whose work we discuss in our next chapter. Let’s turn the page and take a look.