Five

Today I returned to work after four years. A bit more, a bit less, it doesn’t matter, just to make it a round number. All that time I had no serious, formal occupation, or even an informal one, no boss, no rotas, no wage. Without fully realising or feeling guilty about it, allowing the days and the countryside to lead me. There, people work without appearing to, either because they do nothing else or because they do nothing, quite the opposite of the city. I go back to work and in some part of me, through contagion, through defiance, I feel as stupid as I do proud, depending on the moment, generally more the former than the latter.

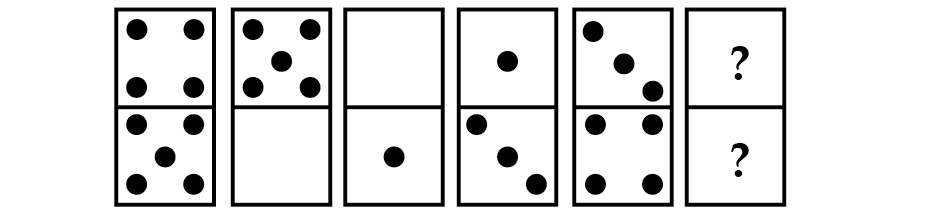

Despite the interview with the human resources man, I received another call from the zoo. This time it was to take psycho-physical tests. First they sent me to a clinic where they measured and weighed me, took a blood sample and an electrocardiogram. A few days later they summoned me to some offices in the centre of town. There, I was met by a girl quite a bit younger than me, probably a psychology student, who interviewed me for twenty minutes, subjecting me to questionnaires, illustrations and logic puzzles. She handed me a test with a hundred questions, beginning with: Do you feel that there aren’t enough hours in the day for all the things you need to do? I answer no to all of them and suspect that something must be wrong. There has to be a trick question somewhere. The girl flicks through it, nods in silence, exposing her lower lip, and says something she immediately regrets: Perfect score. She’s blabbed, rookie mistake. Instructions then follow to draw a house, a tree, a woman and a man, separately, on four blank sheets, and all together on a piece of blue card. Finally, a set of exercises with numbers and geometric shapes that make my eyes ache.

Now that I’m walking along beside the zoo railings, more than once I almost turn back, convinced this isn’t for me, things will sort themselves out, someone will provide for us. But I carry on, to everyone else’s rhythm; this is seemingly what I have to do. I try to picture what it will be like, the greetings, the introductions, the assignment of tasks. I’m out of the habit of dealing with other people, I imagine myself to be awkward, shy. A bit primitive.

I meet Iris at the main door first, for a relay operation. I go in, she comes out, Simón changes hands. The deal is that she’s going to take care of him while I’m working and in return I’ll cook for her at night. She doesn’t want anything else, don’t even mention money. I think about giving her some pointers but as soon as I open my mouth Iris frowns, annoyed in advance; she doesn’t like being told what to do. Simón eases the situation, I move away a few steps and he offers her his hand in a gesture of trust. Sometimes I feel I underestimate him, it must be because of his size, his laconic manner, everything that makes me believe he thinks less than he does. I’m mistaken. After saying goodbye, I spy on them over my shoulder. From a distance, despite the fact that they’re nothing like each other, not in their features or their gestures, even less in the colour of their hair, it would be perfectly natural to think they were mother and son. Iris’s ill-humoured face, her congenital bitterness, the kind that’s not so much an expression of something as a birthmark, anyone would associate with the tedium that some mothers feel no compulsion to conceal when taking their kids for a walk.

I present myself at the booth on República de la India ten minutes before the recommended time, as was suggested to me the last time I spoke to them. Staff entrance. I’m new, I’m starting today, I say. The security man shows his head at the window and for a moment I only have eyes for the fat, soft wart that lengthens his lip like a sleepy, sprawling beetle. The man comes out of his booth to better inspect me, a bloated guy, face like a boxer, with his golden canvas insignias on his shoulders and a badge that says Fortalezza, like that, with a double ‘z’ level with his right nipple. He communicates through his walkie-talkie with someone who speaks back in a broken, short-circuited robot voice. I can’t explain how, but the man understands everything that’s said and conveys the instructions to me. You have to pop into the human resources office to sign the contract, you know how to get there? I nod and give a quick Thanks. I’m welcomed by three camels living amid ruins. On the way to the administration building, I get a bit lost, twice I come out behind the toucan cage until finally I recognise a bower, the bridge and the lake.

In human resources, there’s no sign of the man with spiky hair who interviewed me nor of the boy with freckles. I’m received by a mature woman of about fifty, very polite, who, although she takes a few minutes to work out who I am, becomes enthusiastic as soon as she does, as if she had a real interest in my debut. Take a seat, she says twice, and I decline both times. I have to find you on here, she explains, and draws her face right up to the computer screen, moving the mouse painstakingly, by the millimetre, as if it were a scalpel. There you are, I’ll print it out and that’s it. First she has to fight with the printer, which swallows the pages, crushing them as if rebelling against having to carry out the same task continually. She finally succeeds and hands me the three pages of the contract, which I glance over briefly; I know I’m going to sign it anyway. In a while, after finding me a uniform in my size, she accompanies me to my work post. At the entrance to the reptile house, she introduces me to Yessica, my colleague. That’s what she calls her, your colleague, and adds: I’m leaving you in good hands.

For what’s left of the day, Yessica will make no effort to ease things or help me integrate. Quite the reverse, she’s going to devote herself to making me feel like a nuisance at every opportunity. She has no intention of teaching me anything, she just points out what I’m doing wrong, what I’m not doing, complaining, smacking her lips in a most unpleasant way, like an alien. As if to say: It’s useless, not worth trying, poor little human. As soon as someone else appears, another colleague, one of the security guards, the girl from the bar, not only does she not bother to introduce me but she breaks off whatever she’s saying to me as if I didn’t exist and starts speaking to the person in front of her, throwing out comments that are unsubtly directed at me: What a day or What have I done to deserve this.

Unwillingly, presumably because she doesn’t want any complaints later on and because it’s her job to introduce newcomers to the working environment, Yessica eventually gives me a tour of the reptile house. She lists the names of the animals with an exaggerated lack of enthusiasm as we are already passing them: The boas, the pythons, the caiman, the lizards and further over, the tortoises. But don’t ask me anything, she says as we turn back, I have no idea.

Then, instead of following her, I rebel and return to the start to recommence the visit at a more leisurely pace. I say: I’m going to keep familiarising myself with the terrain. She shrugs, head tilting and eyes bulging, indignant: Who do you think you are, it would seem she’s going to say to me, but no, she keeps quiet. Some animals, because of their name, size or position, intrigue me more than others, they force me to stop walking and approach the glass that separates us. Above each species there’s a lit panel with information detailing dietary habits, behaviour, method of reproduction and habitat zones coloured in on a world map. There are hidden snakes that don’t show their faces, camouflaged behind the artificial trunks that make up their micro-world, others aren’t visible at all, very few of them moving, only one is looking out, the royal python. I read the sheet with the intention of memorising it: nocturnal habits, mostly land-based, areas of undergrowth, tall forest grasses, excellent swimmers. They hunt by lying in wait on the ground or in trees. Oviparous and carnivorous. They feed on small mammals, especially rodents. Also known as the ball python, their colouration varies from browns to ochres and golds. Average lifespan: twenty to twenty-five years. Location: west coast of Africa, from Angola to Senegal, also Zaire, Uganda and Sudan.

I also study the boa constrictor and the rainbow boa, neither of which is venomous; like the royal python they kill their prey by coiling round it until it suffocates. The rainbow boa is found in arid zones. Pastures in Central and South America. The constrictor has a very wide-ranging habitat, from high summits to sea level. It can be found not far from here, in Córdoba, Mendoza and San Luis.

Further along are the green iguana, the broad-snouted caiman and the American alligator. I leave them for another day. Something about the gloomy light, the smell of enclosure, the watchfulness of the snakes in captivity, produces a hole in my stomach, an anguish that forces me to increase my pace. I skirt the large tank of water turtles, ignore the lizards, walk past a door saying nursery and go outside.

A corridor of reeds, and I come out behind the polar bear’s pool. The keeper, I assume he’s their keeper, throws me a friendly smile: Are you lost or trying to escape? I like him. He’s a good-looking boy, with a man’s face, very hairy. On his arms and chest, as well as his hands, forehead and cheeks. He shows me the way back but he’s clearly keen because he stops what he’s doing, resting a long stick with a kind of rubber handle at the end against the railing, and approaches, coming to stand next to me: I’ll go with you. When did you start? he asks, and my response: Today, an hour ago. He laughs and I join in. I point at the reptile house like a little girl who’s relieved to recognise her own house after an excursion that took her too far. I raise my hand to thank him, but he insists on accompanying me. Seeing us arrive, Yessica gets down from her stool and opens her eyes wide. The boy says: We got lost. Yessica lets out a harsh laugh, exaggerated and porcine, and I begin to feel the irritation growing inside me.

The rest of the afternoon goes by with no major incidents. I pick up in passing from conversations between Yessica and another employee who stops off on his way to the office that the school holidays begin on Friday, and from Saturday on, this place will be mental with little brats. That’s what I hear: mental with little brats.

We get a twenty-minute break every shift to go to the toilet, smoke, do whatever you want, Yessica explains to me without taking her eyes off her mobile phone – she’s reading a message, searching for a number, playing solitaire, I don’t know. She raises her head and says: I’ll go first and when I come back you can go for a bit, ok? Yes, I say with a smile that doesn’t quite manage to be ironic. For the first time that day I sit on her stool ready to check tickets. I don’t see much action, only a pair of tiny pensioners. I pass the time watching what’s going on at the food stand opposite, painted with the colours and logo of Coca-Cola and surrounded by ducks. The girl working at the bar doesn’t have many clients either; she entertains herself moving a cloth over the counter, arranging the plastic cups, restocking the drink and popcorn machines. After a while she takes a break, leaning on her elbows next to the till, chin on her closed fist, and she looks in my direction. There we are, eyeing each other up until the sunlight forces us to squint. Not so much out of embarrassment but so as not to make her feel uncomfortable, I take advantage of a shout and avert my gaze: Look, Daddy, a peacock. Indeed it is, unfurling itself between the small canal and the red Coca-Cola chairs. A peacock.

Now you can go, Yessica tells me, and I obey even though I don’t really know where to go. I take ten steps and stop short. Disconcerted, I look in both directions and Yessica, who hasn’t stopped watching me, points out a circular construction surrounded by very tall pines before the feline cage. On the way, I come across a guy with a large broom who looks at me for so long that I end up greeting him. He introduces himself: Canetti, with a double t, head janitor. The dark shadows on his face make him look as though he has two black eyes. He’s lame and cross-eyed, obliquely: he drags his left leg and his right eye looks up to the corner. His lip trembles as if he’s received a low-intensity electric shock. He’s worked in the zoo for seven years. Seven years, he repeats, do you realise? I go into the toilet, I sit down to pee but don’t do anything, I splash my face with water and in the mirror I see myself dressed as an explorer for the first time. Another me. When I come out the guy is still there. He accompanies me to the reptile house, describing the terrain with a cigarette in his mouth. You’ll find everything here, he says and stresses, separating the syllables: Ev-ry-thing. He speaks well of some colleagues but slags most of them off. We say goodbye with a friendly handshake.

At around six, nearly closing time, Esteban appears, the vet in charge of the reptiles. A skinny, bald guy. Yessica introduces us. My first impression is pleasant: frank eyes and babyish skin. During the short time he spends coming and going along the aisles giving instructions to a boy who I suppose must do the dirty work – clean the cages, feed the animals, wash them – I think about approaching Esteban but I don’t know how to. I’d like to tell him, he has no reason to know, that I was going to be a vet too. As if I need to make it clear that I’m not here by chance, like in a kiosk or tollbooth. Luckily, I never find the right moment.

At the end of the shift – working days aren’t days, they’re shifts – in the changing room, as I swap my uniform for my street clothes, I feel as though I’m in a film. Yessica undresses at my side, she walks around in bra and pants as if unintentionally, her body firm, plastic, bulky. Without looking at me, she chats to another girl about a cream for varicose veins.

When I arrive at the Fénix, Iris and Simón are watching television in the kitchen, a programme with water games. How was it? Fine, strange, I almost got bitten by a viper, I say. Iris acknowledges my joke by spitting out one of her Slavic sniggers. Simón is on good form, even better than when he’s with me. We go to the shop, I buy tomatoes, a bag of rice and two tins of tuna.

During the night, an unexpected wind gets up which brings us some relief. In the courtyard, with a slowly warming beer, Iris tells me stories about snakes. Her aunt Lena became rich all of a sudden, thanks to perestroika, when her husband started to dance in petrol, that’s what Iris says and I can’t help imagining them dripping in black goo in the middle of a nightclub dance floor. Her aunt, who had always been a worker, didn’t know what to do with the money. She got bored. First she became obsessed with tattoos and had about a hundred done. Everywhere, arms, legs, back. Even on her arse, she says and laughs loudly. Then she began to collect pets, from the conventional – chihuahuas, Siamese cats, hamsters – to the exotic – tarantulas, frogs and pythons. Pythons? Yes, yes. Once Iris accompanied her aunt to a fair on the outskirts of Moscow, a neighbourhood for the poor, she calls it, to buy mice. Three or four, depending on the size, which she, Aunt Lena, tied head to tail with thread so that the python wouldn’t get in a muddle when the time came to eat them. As he grew, the beast became voracious. So, not to save money but for the sake of convenience, Aunt Lena chose to set up a rat nursery in the laundry of the apartment, one of the most luxurious in Moscow. Listening to Iris makes me think of Esteban and I decide that next time I see him I’m going to mention it. I find it hard to believe that the zoo would feed animals with rats. But it could be true.

With her anecdote about Aunt Lena pursuing the snake down the stairs of the apartment block, Iris reveals a side of herself I never suspected, she’s quite the dramatic raconteur. It would seem that through a maid’s negligence, the python escaped from the apartment. That Aunt Lena went round knocking on all the neighbours’ doors, floor by floor, all of them rich like her, businessmen, artists, mafiosi, diplomats, and when she got to the ground floor, she found it writhing in a corner of the staircase about to be attacked by the caretaker with an axe. That Lena pushed the man away and embraced her pet, sheltering it under her silk pyjamas and that a woman fainted right there. Lena apologised and got into the lift. Izviní, izviní, repeats Iris, imitating her aunt, and runs out to the corridor leading to the patio with a tea towel under her blouse like an imaginary serpent. She comes back in shaking her head and rounds off the story with a snotty guffaw, just like the roar of a bear.