1665–1666

By this it appears how necessary it is for any man that aspires to true knowledge, to examine the definitions of former authors; and either to correct them, where they are negligently set down, or to make them himself. For the errors of definitions multiply themselves according as the reckoning proceeds, and lead men into absurdities, which at last they see, but cannot avoid, without reckoning anew from the beginning.

—HOBBES, Leviathan

JOHN COMSTOCK’S SEAT was at Epsom, a short journey from London. It was large. That largeness came in handy during the Plague, because it enabled his Lordship to stable a few Fellows of the Royal Society (which would enhance his already tremendous prestige) without having to be very close to them (which would disturb his household, and place his domestic animals in extreme peril). All of this was obvious enough to Daniel as one of Comstock’s servants met him at the gate and steered him well clear of the manor house and across a sort of defensive buffer zone of gardens and pastures to a remote cottage with an oddly dingy and crowded look to it.

To one side lay a spacious bone-yard, chalky with skulls of dogs, cats, rats, pigs, and horses. To the other, a pond cluttered with the wrecks of model ships, curiously rigged. Above the well, some sort of pulley arrangement, and a rope extending from the pulley, across a pasture, to a half-assembled chariot. On the roof of the cottage, diverse small windmills of outlandish design—one of them mounted over the mouth of the cottage’s chimney and turned by the rising of its smoke. Every high tree-limb in the vicinity had been exploited as a support for pendulums, and the pendulum-strings had all gotten twisted round each other by winds, and merged into a tattered philosophickal cobweb. The green space in front was a mechanical phant’sy of wheels and gears, broken or never finished. There was a giant wheel, apparently built so that a man could roll across the countryside by climbing inside it and driving it forward with his feet.

Ladders had been leaned against any wall or tree with the least ability to push back. Halfway up one of the ladders was a stout, fair-haired man who was not far from the end of his natural life span—though he apparently did not entertain any ambitions of actually reaching it. He was climbing the ladder one-handed in hard-soled leather shoes that were perfectly frictionless on the rungs, and as he swayed back and forth, planting one foot and then the next, the ladder’s feet, down below him, tiptoed backwards. Daniel rushed over and braced the ladder, then forced himself to look upwards at the shuddering battle-gammoned form of the Rev. Wilkins. The Rev. was carrying, in his free hand, some sort of winged object.

And speaking of winged objects, Daniel now felt himself being tickled, and glanced down to find half a dozen honeybees had alighted on each one of his hands. As Daniel watched in empirical horror, one of them drove its stinger into the fleshy place between his thumb and index finger. He bit his lip and looked up to see whether letting go the ladder would lead to the immediate death of Wilkins. The answer: yes. Bees were now swarming all round—nuzzling the fringes of Daniel’s hair, playing crack-the-whip through the ladder’s rungs, and orbiting round Wilkins’s body in a humming cloud.

Reaching the highest possible altitude—flagrantly tempting the LORD to strike him dead—Wilkins released the toy in his hand. Whirring and clicking noises indicated that some sort of spring-driven clockwork had gone into action—there was fluttering, and skidding through the air—some sort of interaction with the atmosphere, anyway, that went beyond mere falling—but fall it did, veering into the cottage’s stone wall and spraying parts over the yard.

“Never going to fly to the moon that way,” Wilkins grumbled.

“I thought you wanted to be shot out of a cannon to the Moon.”

Wilkins whacked himself on the stomach. “As you can see, I have far too much vis inertiae to be shot out of anything to anywhere. Before I come down there, are you feeling well, young man? No sweats, chills, swellings?”

“I anticipated your curiosity on that subject, Dr. Wilkins, and so the frogs and I lodged at an inn in Epsom for two nights. I have never felt healthier.”

“Splendid! Mr. Hooke has denuded the countryside of small animals—if you hadn’t brought him anything, he’d have cut you up.” Wilkins was coming down the ladder, the sureness of each footfall very much in doubt, massy buttocks approaching Daniel as a spectre of doom. Finally on terra firma, he waved a hundred bees off with an intrepid sweep of the arm. They wiped bees away from their palms, then exchanged a long, warm handshake. The bees were collectively losing interest and seeping away in the direction of a large glinting glass box. “It is Wren’s design, come and see!” Wilkins said, bumbling after them.

The glass structure was a model of a building, complete with a blown dome, and pillars carved of crystal. It was of a Gothickal design, and had the general look of some Government office in London, or a University college. The doors and windows were open to let bees fly in and out. They had built a hive inside—a cathedral of honeycombs.

“With all respect to Mr. Wren, I see a clash of architectural styles here—”

“What! Where?” Wilkins exclaimed, searching the roofline for aesthetic contaminants. “I shall cane the boy!”

“It’s not the builder, but the tenants who’re responsible. All those little waxy hexagons—doesn’t fit with Mr. Wren’s scheme, does it?”

“Which style do you prefer?” Wilkins asked, wickedly.

“Err—”

“Before you answer, know that Mr. Hooke approaches,” the Rev. whispered, glancing sidelong. Daniel looked over toward the house to see Hooke coming their way, bent and gray and transparent, like one of those curious figments that occasionally floats across one’s eyeball.

“Is he all right?” Daniel asked.

“The usual bouts of melancholy—a certain peevishness over the scarcity of adventuresome females—”

“I meant is he sick.”

Hooke had stopped near Daniel’s luggage, attracted by the croaking of frogs. He stepped in and seized the basket.

“Oh, he ever looks as if he’s been bleeding to death for several hours—fear for the frogs, not for Hooke!” Wilkins said. He had a perpetual knowing, amused look that enabled him to get away with saying almost anything. This, combined with the occasional tactical master-stroke (e.g., marrying Cromwell’s sister during the Interregnum), probably accounted for his ability to ride out civil wars and revolutions as if they were mere theatrical performances. He bent down in front of the glass apiary, pantomiming a bad back; reached underneath; and, after some dramatic rummaging, drew out a glass jar with an inch or so of cloudy brown honey in the bottom. “Mr. Wren provided sewerage, as you can see,” he said, giving the jar to Daniel. It was blood-warm. The Rev. now headed in the direction of the house, and Daniel followed.

“You say you quarantined yourself at Epsom town—you must have paid for lodgings there—that means you have pocket-money. Drake must’ve given it you. What on earth did you tell him you were coming here to do? I need to know,” Wilkins added apologetically, “only so that I can write him the occasional letter claiming that you are doing it.”

“Keeping abreast of the very latest, from the Continent or whatever. I’m to provide him with advance warning of any events that are plainly part of the Apocalypse.”

Wilkins stroked an invisible beard and nodded profoundly, standing back so that Daniel could dart forward and haul open the cottage door. They went into the front room, where a fire was decaying in a vast hearth. Two or three rooms away, Hooke was crucifying a frog on a plank, occasionally swearing as he struck his thumb. “Perhaps you can help me with my book…”

“A new edition of the Cryptonomicon?”

“Perish the thought! Damn me, I’d almost forgotten about that old thing. Wrote it a quarter-century ago. Consider the times! The King was losing his mind—his Ministers being lynched in Parliament—his own drawbridge-keepers locking him out of his own arsenals. His foes intercepting letters abroad, written by that French Papist wife of his, begging foreign powers to invade us. Hugh Peters had come back from Salem to whip those Puritans into a frenzy—no great difficulty, given that the King, simply out—out—of money, had seized all of the merchants’ gold in the Tower. Scottish Covenanters down as far as Newcastle, Catholics rebelling in Ulster, sudden panics in London—gentlemen on the street whipping out their rapiers for little or no reason. Things no better elsewhere—Europe twenty-five years into the Thirty Years’ War, wolves eating children along the road in Besançon, for Christ’s sake—Spain and Portugal dividing into two separate kingdoms, the Dutch taking advantage of it to steal Malacca from the Portuguese—of course I wrote the Cryptonomicon! And of course people bought it! But if it was the Omega—a way of hiding information, of making the light into darkness—then the Universal Character is the Alpha—an opening. A dawn. A candle in the darkness. Am I being disgusting?”

“Is this anything like Comenius’s project?”

Wilkins leaned across and made as if to box Daniel’s ears. “It is his project! This was what he and I, and that whole gang of odd Germans—Hartlib, Haak, Kinner, Oldenburg—wanted to do when we conceived the Invisible College* back in the Dark Ages. But Mr. Comenius’s work was burned up in a fire, back in Moravia, you know.”

“Accidental, or—”

“Excellent question, young man—in Moravia, one never knows. Now, if Comenius had listened to my advice and accepted the invitation to be Master of Harvard College back in ’41, it might’ve been different—”

“The colonists would be twenty-five years ahead of us!”

“Just so. Instead, Natural Philosophy flourishes at Oxford—less so at Cambridge—and Harvard is a pitiable backwater.”

“Why didn’t he take your advice, I wonder—?”

“The tragedy of these middle-European savants is that they are always trying to apply their philosophick acumen in the political realm.”

“Whereas the Royal Society is—?”

“Ever so strictly apolitical,” Wilkins said, and then favored Daniel with a stage-actor’s hugely exaggerated wink. “If we stayed away from politics, we could be flying winged chariots to the Moon within a few generations. All that’s needed is to pull down certain barriers to progress—”

“Such as?”

“Latin.”

“Latin!? But Latin is—”

“I know, the universal language of scholars and divines, et cetera, et cetera. And it sounds so lovely, doesn’t it. You can say any sort of nonsense in Latin and our feeble University men will be stunned, or at least profoundly confused. That’s how the Popes have gotten away with peddling bad religion for so long—they simply say it in Latin. But if we were to unfold their convoluted phrases and translate them into a philosophical language, all of their contradictions and vagueness would become manifest.”

“Mmm…I’d go so far as to say that if a proper philosophical language existed, it would be impossible to express any false concept in it without violating its rules of grammar,” Daniel hazarded.

“You have just uttered the most succinct possible definition of it—I say, you’re not competing with me, are you?” Wilkins said jovially.

“No,” Daniel said, too intimidated to catch the humor. “I was merely reasoning by analogy to Cartesian analysis, where false statements cannot legally be written down, as long as the terms are understood.”

“The terms! That’s the difficult part,” Wilkins said. “As a way to write down the terms, I am developing the Philosophical Language and the Universal Character—which learned men of all races and nations will use to signify ideas.”

“I am at your service, sir,” Daniel said. “When may I begin?”

“Immediately! Before Hooke’s done with those frogs—if he comes in here and finds you idle, he’ll enslave you—you’ll be shovelling guts or, worse, trying the precision of his clocks by standing before a pendulum and counting…its…alternations…all…day…long.”

Hooke came in. His spine was all awry: not only stooped, but bent to one side. His long brown hair hung unkempt around his face. He straightened up a bit and tilted his head back so that the hair fell away to either side, like a curtain opening up to reveal a pale face. Stubble on the cheeks made him look even gaunter than he actually was, and made his gray eyes look even more huge. He said: “Frogs, too.”

“Nothing surprises me now, Mr. Hooke.”

“I put it to you that all living creatures are made out of them.”

“Have you considered writing any of this down? Mr. Hooke? Mr. Hooke?” But Hooke was already gone out into the stable-yard, off on some other experiment.

“Made out of what??” Daniel asked.

“Lately, every time Mr. Hooke peers at something with his Microscope he finds that it is divided up into small compartments, each one just like its neighbors, like bricks in a wall,” Wilkins confided.

“What do these bricks look like?”

“He doesn’t call them bricks. Remember, they are hollow. He has taken to calling them ‘cells’…but you don’t want to get caught up in all that nonsense. Follow me, my dear Daniel. Put thoughts of cells out of your mind. To understand the Philosophical Language you must know that all things in Earth and Heaven can be classified into forty different genera…within each of those, there are, of course, further subclasses.”

Wilkins showed him into a servant’s room where a writing desk had been set up, and papers and books mounded up with as little concern for order as the bees had shown in building their honeycomb. Wilkins moved a lot of air, and so leaves of paper flew off of stacks as he passed through the room. Daniel picked one up and read it: “Mule fern, panic-grass, hartstongue, adderstongue, moon-wort, sea novelwort, wrack, Job’s-tears, broomrope, toothwort, scurvy-grass, sowbread, golden saxifrage, lily of the valley, bastard madder, stinking ground-pine, endive, dandelion, sowthistle, Spanish picktooth, purple loose-strife, bitter vetch.”

Wilkins was nodding impatiently. “The capsulate herbs, not campanulate, and the bacciferous sempervirent shrubs,” he said. “Somehow it must have gotten mixed up with the glandiferous and the nuciferous trees.”

“So, the Philosophical Language is some sort of botanical—”

“Look at me, I’m shuddering. Shuddering at the thought. Botany! Please, Daniel, try to collect your wits. In this stack we have all of the animals, from the belly-worm to the tyger. Here, the terms of Euclidean geometry, relating to time, space, and juxtaposition. There, a classification of diseases: pustules, boils, wens, and scabs on up to splenetic hypochondriacal vapours, iliac passion, and suffocation.”

“Is suffocation a disease?”

“Excellent question—get to work and answer it!” Wilkins thundered.

Daniel, meanwhile, had rescued another sheet from the floor: “Yard, Johnson, dick…”

“Synonyms for ‘penis,’” Wilkins said impatiently.

“Rogue, mendicant, shake-rag…”

“Synonyms for ‘beggar.’ In the Philosophical Language there will only be one word for penises, one for beggars. Quick, Daniel, is there a distinction between groaning and grumbling?”

“I should say so, but—”

“On the other hand—may we lump genuflection together with curtseying, and give them one name?”

“I—I cannot say, Doctor!”

“Then, I say, there is work to be done! At the moment, I am bogged down in an endless digression on the Ark.”

“Of the Covenant? Or—”

“The other one.”

“How does that enter into the Philosophical Language?”

“Obviously the P.L. must contain one and only one word for every type of animal. Each animal’s word must reflect its classification—that is, the words for perch and bream should be noticeably similar, as should the words for robin and thrush. But bird-words should be quite different from fish-words.”

“It strikes me as, er, ambitious…”

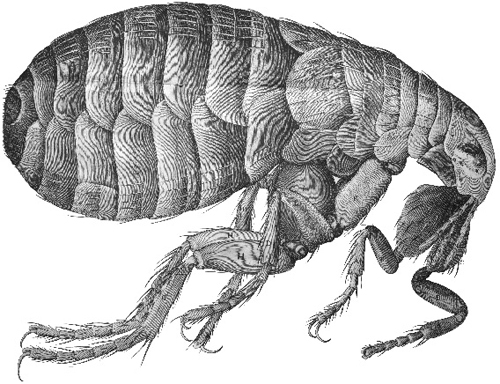

“Half of Oxford is sending me tedious lists. My—our—task is to organize them—to draw up a table of every type of bird and beast in the world. I have entabulated the animals troublesome to other animals—the louse, the flea. Those designed for further transmutation—the caterpillar, the maggot. One-horned sheathed winged insects. Testaceous turbinated exanguious animals—and before you ask, I have subdivided them into those with, and without, spiral convolutions. Squamous river fish, phytivorous birds of long wings, rapacious beasts of the cat-kind—anyway, as I drew up all of these lists and tables, it occurred to me that (going back to Genesis, sixth chapter, verses fifteen through twenty-two) Noah must have found a way to fit all of these creatures into one gopher-wood tub three hundred cubits long! I became concerned that certain Continental savants, of an atheistical bent, might misuse my list to suggest that the events related in Genesis could not have happened—”

“One could also imagine certain Jesuits turning it against you—holding it up as proof that you harbored atheistical notions of your own, Dr. Wilkins.”

“Just so! Daniel! Which makes it imperative that I include, in a separate chapter, a complete plan of Noah’s Ark—demonstrating not only where each of the beasts was berthed, but also the fodder for the herbivorous beasts, and live cattle for the carnivorous ones, and more fodder yet to keep the cattle alive, long enough to be eaten by the carnivores—where, I say, ’twas all stowed.”

“Fresh water must have been wanted, too,” Daniel reflected.

Wilkins—who tended to draw closer and closer to people when he was talking to them, until they had to edge backwards—grabbed a sheaf of paper off a stack and bopped Daniel on the head with it. “Tend to your Bible, foolish young man! It rained the entire time!”

“Of course, of course—they could’ve drunk rainwater,” Daniel said, profoundly mortified.

“I have had to take some liberties with the definition of ‘cubit,’” Wilkins said, as if betraying a secret, “but I think he could have done it with eighteen hundred and twenty-five sheep. To feed the carnivores, I mean.”

“The sheep must’ve taken up a whole deck!?”

“It’s not the space they take up, it’s all the manure, and the labor of throwing it overboard,” Wilkins said. “At any rate—as you can well imagine—this Ark business has stopped all progress cold on the P.L. front. I need you to get on with the Terms of Abuse.”

“Sir!”

“Have you felt, Daniel, a certain annoyance, when one of your semi-educated Londoners speaks of ‘a vile rascal’ or ‘a miserable caitiff’ or ‘crafty knave,’ ‘idle truant,’ or ‘flattering parasite’?”

“Depends upon who is calling whom what…”

“No, no, no! Let’s try an easy one: ‘fornicating whore.’ ”

“It is redundant. Hence, annoying to the cultivated listener.”

“Again, redundant—as are ‘flattering parasite’ and the others.”

“So, clearly, in the Philosophical Language, we needn’t have separate adjectives and nouns in such cases.”

“How about ’filthy sloven?”

“Excellent! Write it down, Daniel!”

“‘Licentious blade’…‘facetious wag’…‘perfidious traitor’…” As Daniel continued in this vein, Wilkins bustled over to the writing-desk, withdrew a quill from an inkwell, shook off redundant ink, and then came over to Daniel; wrapped his fingers around the pen; and guided him over to the desk.

And so to work. Daniel exhausted the Terms of Abuse in a few short hours, then moved on to Virtues (intellectual, moral, and homiletical), Colors, Sounds, Tastes and Smells, Professions, Operations (viz. carpentry, sewing, alchemy), and so on. Days began passing. Wilkins became fretful if Daniel, or anyone, worked too hard, and so there were frequent “seminars” and “symposia” in the kitchen—they used honey from Christopher Wren’s Gothic apiary to make flip. Frequently Charles Comstock, the fifteen-year-old son of their noble host, came to visit, and to hear Wilkins or Hooke talk. Charles tended to bring with him letters addressed to the Royal Society from Huygens, Leeuwenhoek, Swammerdam, Spinoza. Frequently these turned out to contain new concepts that Daniel had to fit into the Philosophical Language’s tables.

Daniel was hard at work compiling a list of all the things in the world that a person could own (aquæducts, axle-trees, palaces, hinges) when Wilkins called him down urgently. Daniel came down to find the Rev. holding a grand-looking Letter, and Charles Comstock clearing the decks for action: rolling up large diagrams of the Ark, and feeding-schedules for the eighteen hundred and twenty-five sheep, and stowing them out of the way to make room for more important affairs. Charles II, by the Grace of God of England King, had sent them this letter: His Majesty had noticed that ant eggs were bigger than ants, and demanded to know how that was possible.

Daniel ran out and sacked an ant-nest. He returned in triumph carrying the nucleus of an anthill on the flat of a shovel. In the front room Wilkins had begun dictating, and Charles Comstock scribbling, a letter back to the King—not the substantive part (as they didn’t have an answer yet), but the lengthy paragraphs of apologies and profuse flattery that had to open it: “With your brilliance you illuminate the places that have long, er, languished in, er—”

“Sounds more like a Sun King allusion, Reverend,” Charles warned him.

“Strike it, then! Sharp lad. Read the entire mess back to me.”

Daniel slowed before the door to Hooke’s laboratory, gathering his courage to knock. But Hooke had heard him approaching, and opened it for him. With an outstretched hand he beckoned Daniel in, and aimed him at a profoundly stained table, cleared for action. Daniel entered the room, upended the ant-nest, set the shovel down, and only then worked up the courage to inhale. Hooke’s laboratory didn’t smell as bad as he’d always assumed it would.

Hooke ran his hands back through his hair, pulling it away from his face, and tied it back behind his neck with a wisp of twine. Daniel was perpetually surprised that Hooke was only ten years older than he. Hooke just turned thirty a few weeks ago, in June, at about the same time that Daniel and Isaac had fled plaguey Cambridge for their respective homes.

Hooke was now staring at the mound of living dirt on his table-top. His eyes were always focused on a narrow target, as if he peered out at the world through a hollow reed. When he was out in the broad world, or even in the house’s front room, that seemed strange, but it made sense when he was looking at a small world on a tabletop—ants scurrying this way and that, carrying egg-cases out of the wreckage, establishing a defensive perimeter. Daniel stood opposite and looked at, but apparently did not see, the same things.

Within a few minutes Daniel had seen most of what he was going to see among the ants, within five minutes he was bored, within ten he had given up all pretenses and begun wandering round Hooke’s laboratory, looking at the remnants of everything that had passed beneath the microscope: shards of porous stone, bits of moldy shoe-leather, a small glass jar labelled WILKINS URINE, splinters of petrified wood, countless tiny envelopes of seeds, insects in jars, scraps of various fabrics, tiny pots labelled SNAILS TEETH and VIPERS FANGS. Shoved back into a corner, a heap of dusty, rusty sharp things: knife-blades, needles, razors. There was probably a cruel witticism to be made here: given a razor, Hooke would sooner put it under his microscope than shave with it.

As the wait went on, and on, and on, Daniel decided that he might as well be improving himself. So with care he reached into the sharp-things pile, drew out a needle, and carried it over to a table where sun was pouring in (Hooke had grabbed all of the south-facing rooms in the cottage, to own the light). There, mounted to a little stand, was a tube, about the dimensions of a piece of writing-paper rolled up, with a lens at the top for looking through, and a much smaller one—hardly bigger than a chick’s eye—at the bottom, aimed at a little stand that was strongly illuminated by the sunlight. Daniel put the needle on the stand and peered through the Microscope.

He expected to see a gleaming, mirrorlike shaft, but it was a gnawed stick instead. The needle’s sharp point turned out to be a rounded and pitted slag-heap.

“Mr. Waterhouse,” Hooke said, “when you are finished with whatever you are doing, I will consult my faithful Mercury.”

Daniel stood up and turned around. He thought for a moment that Hooke was asking him to fetch some quicksilver (Hooke drank it from time to time, as a remedy for headaches, vertigo, and other complaints). But Hooke’s giant eyes were focused on the Microscope instead.

“Of course!” Daniel said. Mercury, the Messenger of the Gods—bringer of information.

“What think you now of needles?” Hooke asked.

Daniel plucked the needle away and held it up before the window, viewing it in a new light. “Its appearance is almost physically disgusting,” he said.

“A razor looks worse. It is all kinds of shapes, except what it should be,” Hooke said. “That is why I never use the Microscope any more to look at things that were made by men—the rudeness and bungling of Art is painful to view. And yet things that one would expect to look disgusting become beautiful when magnified—you may look at my drawings while I satisfy the King’s curiosity.” Hooke gestured to a stack of papers, then carried a sample ant-egg over to the microscope as Daniel began to page through them.

“Sir. I did not know that you were an artist,” Daniel said.

“When my father died, I was apprenticed to a portrait-painter,” Hooke said.

“Your master taught you well—”

“The ass taught me nothing,” Hooke said. “Anyone who is not a half-wit can learn all there is to know of painting, by standing in front of paintings and looking at them. What was the use, then, of being an apprentice?”

“This flea is a magnificent piece of—”

“It is not art but a higher form of bungling,” Hooke demurred. “When I viewed that flea under the microscope, I could see, in its eye, a complete and perfect reflection of John Comstock’s gardens and manor-house—the blossoms on his flowers, the curtains billowing in his windows.”

“It’s magnificent to me,” Daniel said. He was sincere—not trying to be a Flattering Parasite or Crafty Knave.

But Hooke only became irritated. “I tell you again. True beauty is to be found in natural forms. The more we magnify, and the closer we examine, the works of Artifice, the grosser and stupider they seem. But if we magnify the natural world it only becomes more intricate and excellent.”

Wilkins had asked Daniel which he preferred: Wren’s glass apiary, or the bees’ honeycomb inside of it. Then he had warned Daniel that Hooke was coming into earshot. Now Daniel understood why: for Hooke there could only be one answer.

“I defer to you, sir.”

“Thank you, sir.”

“But without seeming to be a Cavilling Jesuit, I should like to know whether Wilkins’s urine is a product of Art or Nature.”

“You saw the jar.”

“Yes.”

“If you take the Rev.’s urine and pour off the fluid and examine what remains under the Microscope, you will see a hoard of jewels that would make the Great Mogul swoon. At lower magnification it seems nothing more than a heap of gravel, but with a better lens, and brighter light, it is revealed as a mountain of crystals—plates, rhomboids, rectangles, squares—white and yellow and red ones, gleaming like the diamonds in a courtier’s ring.”

“Is that true of everyone’s urine?”

“It is more true of his than of most people’s,” Hooke said. “Wilkins has the stone.”

“It is not so bad now, but it grows within him, and will certainly kill him in a few years,” Hooke said.

“And the stone in his bladder is made of the same stuff as these crystals that you see in his urine?”

“I believe so.”

“Is there some way to—”

“To dissolve it? Oil of vitriol works—but I don’t suppose that our Reverend wants to have that introduced into his bladder. You are welcome to make investigations of your own. I have tried all of the obvious things.”

WORD ARRIVED THAT FERMAT had died, leaving behind a theorem or two that still needed proving. King Philip of Spain died, too, and his son succeeded him; but the new King Carlos II was sickly, and not expected to live to the end of the year. Portugal was independent. Someone named Lubomirski was staging a rebellion in Poland.

John Wilkins was trying to make horse-drawn vehicles more efficient; to test them, he had rigged up a weight on a rope, above a well, so that when the weight fell down into the well, it would drag his chariots across the ground. Their progress could then be timed using one of Hooke’s watches. That duty fell to Charles Comstock, who spent many days standing out in the field making trials or fixing broken wheels. His father’s servants needed the well to draw water for livestock, and so Charles was frequently called out to move the contraption out of the way. Daniel enjoyed watching all of this, out the window, while he worked on Punishments:

PUNISHMENTS CAPITAL

ARE THE VARIOUS MANNERS OF PUTTING MEN TO DEATH IN A JUDICIAL WAY, WHICH IN SEVERAL NATIONS ARE, OR HAVE BEEN, EITHER SIMPLE; BY

Separation of the parts;

Head from Body: BEHEADING, strike of one’s head

Member from Member: QUARTERING, Dissecting.

Wound

At distance, whether

from hand: STONING, Pelting

from Instrument, as Gun, Bow, &c.: SHOOTING.

At hand, either by

Weapon;

any way: STABBING

direct upwards: EMPALING

Taking away necessary Diet: or giving that which is noxious

STARVING, famishing

POISONING, Venom, envenom, virulent

Interception of the air

at the Mouth

in the air: stifling, smother, suffocate.

in the Earth: BURYING ALIVE

in water: DROWNING

in fire: BURNING ALIVE

at the Throat

by weight of a man’s own body: HANGING

by the strength of others: STRANGLING, throttle, choke, suffocate

MIXED OF WOUNDING AND STARVING; THE BODY BEING

Erect: CRUCIFYING

Lying on a Wheel: BREAKING ON THE WHEEL

PUNISHMENTS NOT CAPITAL

ARE DISTINGUISHED BY THE THINGS OR SUBJECTS RECEIVING DETRIMENT BY THEM, AS BEING EITHER OF THE BODY;

according to the General name; signifying great pain: TORTURE

according to special kinds:

by Striking;

with a limber instrument: WHIPPING, lashing, scourging, leashing, rod, slash, switch, stripe, Beadle

with a stiff instrument: CUDGELLING, bastinado, baste, swinge, swaddle, shrubb, slapp, thwack;

by Stretching of the limbs violently;

the body being laid along: RACK

the body lifted up into the Air: STRAPPADO

LIBERTY; OF WHICH ONE IS DEPRIVED, BY RESTRAINT

into

a place: IMPRISONMENT, Incarceration, Durance, Custody, Ward, clap up, commit, confine, mure, Pound, Pinfold, Gaol, Cage, Set fast an Instrument: BONDS, fetters, gyves, shackles, manicles, pinion, chains.

Out of a place or country, whether

with allowance of any other: EXILE, banishment

confinement to one other: RELEGATION

REPUTE, WHETHER

more gently: INFAMIZATION, Ignominy, Pillory

more severely by burning marks in one’s flesh: STIGMATIZATION, Branding, Cauterizing

ESTATE; WHETHER

in part: MULCT, fine, sconce

in whole: CONFISCATION, forfeiture

DIGNITY AND POWER; BY DEPRIVING ONE OF

his degree: DEGRADING, deposing, depriving

his capacity to bear office: INCAPACITATING, cashier, disable, discard, depose, disfranchize.

As Daniel scourged, bastinadoed, racked, and strappadoed his mind, trying to think of punishments that he and Wilkins had missed, he heard Hooke striking sparks with flint and steel, and went down to investigate.

Hooke was aiming the sparks at a blank sheet of paper. “Mark where they strike,” he said to Daniel. Daniel hovered with a pen, and whenever an especially large spark hit the paper, he drew a tight circle around it. They examined the paper under the Microscope, and found, in the center of each circle, a remnant: a more or less complete hollow sphere of what was obviously steel. “You see that the Alchemists’ conception of heat is ludicrous,” Hooke said. “There is no Element of Fire. Heat is really nothing more than a brisk agitation of the parts of a body—hit a piece of steel with a rock hard enough, and a bit of steel is torn away—”

“And that is the spark?”

“That is the spark.”

“But why does the spark emit light?”

“The force of the impact agitates its parts so vehemently that it becomes hot enough to melt.”

“Yes, but if your hypothesis is correct—if there is no Element of Fire, only a jostling of internal parts—then why should hot things emit light?”

“I believe that light consists of vibrations. If the parts move violently enough, they emit light—just as a struck bell vibrates to produce sound.”

Daniel supposed that was all there was to that, until he went with Hooke to collect samples of river insects one day, and they squatted in a place where a brook tumbled over the brink of a rock into a little pool. Bubbles of water, forced beneath the pool by the falling water, rose to the surface: millions of tiny spheres. Hooke noticed it, pondered for a few moments, and said: “Planets and stars are spheres, for the same reason that bubbles and sparks are.”

“What!?”

“A body of fluid, surrounded by some different fluid, forms into a sphere. Thus: air surrounded by water makes a sphere, which we call a bubble. A tiny bit of molten steel surrounded by air makes a sphere, which we call a spark. Molten earth surrounded by the Cœlestial Æther makes a sphere, which we call a planet.”

And on the way back, as they were watching a crescent moon chase the sun below the horizon, Hooke said, “If we could make sparks, or flashes of light, bright enough, we could see their light reflected off the shadowed part of that moon later, and reckon the speed of light.”

“If we did it with gunpowder,” Daniel reflected, “John Comstock would be happy to underwrite the experiment.”

Hooke turned and regarded him for a few moments with a cold eye, as if trying to establish whether Daniel, too, was made up out of cells. “You are thinking like a courtier,” he said. There was no emotion in his voice; he was stating, not an opinion, but a fact.

The chief Design of the aforementioned Club, was to propagate new Whims, advance mechanic Exercises, and to promote useless, as well as useful Experiments. In order to carry on this commendable Undertaking, any frantic Artist, chemical Operator, or whimsical Projector, that had but a Crotchet in their Heads, or but dream’d themselves into some strange fanciful Discovery, might be kindly admitted, as welcome Brethren, into this teeming Society, where each Member was respected, not according to his Quality, but the searches he had made into the Mysteries of Nature, and the Novelties, though Trifles, that were owing to his Invention: So that a Mad-man, who had beggar’d himself by his Bellows and his Furnaces, in a vain pursuit of the Philosopher’s Stone; or the crazy Physician who had wasted his Patrimony, by endeavouring to recover that infallible Nostrum, Sal Graminis, from the dust and ashes of a burnt Hay-cock, were as much reverenc’d here, as those mechanic Quality, who, to shew themselves Vertuoso’s, would sit turning of Ivory above in their Garrets, whilst their Ladies below Stairs, by the help of their He-Cousins, were providing Horns for their Families.

—NED WARD, The Vertuoso’s Club

THE LEAVES WERE TURNING, the Plague in London was worse. Eight thousand people died in a week. A few miles away in Epsom, Wilkins had finished the Ark digression and begun to draw up a grammar, and a system of writing, for his Philosophical Language. Daniel was finishing some odds and ends, viz. Nautical Objects: Seams and Spurkets, Parrels and Jears, Brales and Bunt-Lines. His mind wandered.

Below him, a strange plucking sound, like a man endlessly tuning a lute. He went down stairs and found Hooke sitting there with a few inches of quill sticking out of his ear, plucking a string stretched over a wooden box. It was far from the strangest thing Hooke had ever done, so Daniel went to work for a time, trying to dissolve Wilkins’s bladder-gravel in various potions. Hooke continued plucking and humming. Finally Daniel went over to investigate.

A housefly was perched on the end of the quill that was stuck in Hooke’s ear. Daniel tried to shoo it away. Its wings blurred, but it didn’t move. Looking more closely Daniel saw that it had been glued down.

“Do that again, it gives me a different pitch,” Hooke demanded.

“You can hear the fly’s wings?”

“They drone at a certain fixed pitch. If I tune this string”—pluck, pluck—“to the same pitch, I know that the string, and the fly’s wings, are vibrating at the same frequency. I already know how to reckon the frequency of a string’s vibration—hence, I know how many times in a second a fly’s wings beat. Useful data if we are ever to build a flying-machine.”

Autumn rain made the field turn mucky, and ended the chariot experiments. Charles Comstock had to find other things to do. He had matriculated at Cambridge this year, but Cambridge was closed for the duration of the Plague. Daniel reckoned that as a quid pro quo for staying here at Epsom, Wilkins was obliged to tutor Charles in Natural Philosophy. But most of the tutoring was indistinguishable from drudge work on Wilkins’s diverse experiments, many of which (now that the weather had turned) were being conducted in the cottage’s cellar. Wilkins was starving a toad in a jar to see if new toads would grow out of it. There was a carp living out of water, being fed on moistened bread; Charles’s job was to wet its gills several times a day. The King’s ant question had gotten Wilkins going on an experiment he’d wanted to try for a long time: before long, down in the cellar, between the starving toad and the carp, they had a maggot the size of a man’s thigh, which had to be fed rotten meat, and weighed once a day. This began to smell and so they moved it outside, to a shack downwind, where Wilkins had also embarked on a whole range of experiments concerning the generation of flies and worms out of decomposing meat, cheese, and other substances. Everyone knew, or thought they knew, that this happened spontaneously. But Hooke with his microscope had found tiny motes on the undersides of certain leaves, which grew up into insects, and in water he had found tiny eggs that grew up into gnats, and this had given him the idea that perhaps all things that were believed to be bred from putrefaction might have like origins: that the air and the water were filled with an invisible dust of tiny eggs and seeds that, in order to germinate, need only be planted in something moist and rotten.

From time to time, a carriage or wagon from the outside world was suffered to pass into the gate of the manor and approach the big house. On the one hand, this was welcome evidence that some people were still alive out there in England. On the other—

“Who is that madman, coming and going in the midst of the Plague,” Daniel asked, “and why does John Comstock let him into his house? The poxy bastard’ll infect us all.”

“John Comstock could not exclude that fellow any more than he could ban air from his lungs,” Wilkins said. He had been tracking the carriage’s progress, at a safe distance, through a prospective glass. “That is his money-scrivener.”

Daniel had never heard the term before. “I have not yet reached that point in the Tables where ‘money-scrivener’ is defined. Does he do what a goldsmith does?”

“Smite gold? No.”

“Of course not. I was referring to this new line of work that goldsmiths have got into—handling notes that serve as money.”

“A man such as the Earl of Epsom would not suffer a money-goldsmith to draw within a mile of his house!” Wilkins said indignantly. “A money-scrivener is different altogether! And yet he does something very much the same.”

“Could you explain that, please?” Daniel said, but they were interrupted by Hooke, shouting from another room:

“Daniel! Fetch a cannon.”

In other circumstances this demand would have posed severe difficulties. However, they were living on the estate of the man who had introduced the manufacture of gunpowder to Britain, and provided King Charles II with many of his armaments. So Daniel went out and enlisted that man’s son, young Charles Comstock, who in turn drafted a corps of servants and a few horses. They procured a field-piece from John Comstock’s personal armoury and towed it out into the middle of a pasture. Meanwhile, Mr. Hooke had caused a certain servant, who had long been afflicted with deafness, to be brought out from the town. Hooke bade the servant stand in the same pasture, only a fathom away from the muzzle of the cannon (but off to one side!). Charles Comstock (who knew how to do such things) charged the cannon with some of his father’s finest powder, shoved a longish fuse down the touch-hole, lit it, and ran away. The result was a sudden immense compression of the air, which Hooke had hoped would penetrate the servant’s skull and knock away whatever hidden obstructions had caused him to become deaf. Quite a few window-panes in John Comstock’s manor house were blown out of their frames, amply demonstrating the soundness of the underlying idea. But it didn’t cure the servant’s deafness.

“As you may know, my dwelling is a-throng, just now, with persons from the city,” said John Comstock, Earl of Epsom and Lord Chancellor of England.

He had appeared, suddenly and unannounced, in the door of the cottage. Hooke and Wilkins were busy hollering at the deaf servant, trying to see if he could hear anything at all. Daniel noticed the visitor first, and joined in the shouting: “Excuse me! Gentlemen! REVEREND WILKINS!”

After several minutes’ confusion, embarrassment, and makeshift stabs at protocol, Wilkins and Comstock ended up sitting across the table from each other with glasses of claret while Hooke and Waterhouse and the deaf servant held up a nearby wall with their arses.

Comstock was pushing sixty. Here on his own country estate, he had no patience with wigs or other Court foppery, and so his silver hair was simply queued, and he was dressed in plain simple riding-and-hunting togs. “In the year of my birth, Jamestown was founded, the pilgrims scurried off to Leyden, and work commenced on the King James version of the Bible. I have lived through London’s diverse riots and panics, plagues and Gunpowder Plots. I have escaped from burning buildings. I was wounded at the Battle of Newark and made my way, in some discomfort, to safety in Paris. It was not my last battle, on land or at sea. I was there when His Majesty was crowned in exile at Scone, and I was there when he returned in triumph to London. I have killed men. You know all of these things, Dr. Wilkins, and so I mention them, not to boast, but to emphasize that if I were living a solitary life in that large House over yonder, you could set off cannonades, and larger detonations, at all hours of day and night, without warning, and for that matter you could make a pile of meat five fathoms high and let it fester away beneath my bedchamber’s window—and none of it would matter to me. But as it is, my house is crowded, just now, with Persons of Quality. Some of them are of royal degree. Many of them are female, and some are of tender years. Two of them are all three.”

“My lord!” Wilkins exclaimed. Daniel had been carefully watching him, as who wouldn’t—the opportunity to watch a man like Wilkins being called on the carpet by a man like Comstock was far more precious than any Southwark bear-baiting. Until just now, Wilkins had pretended to be mortified—though he’d done a very good job of it. But now, suddenly, he really was.

Two of them are all three—what could that possibly mean? Who was royal, female, and of tender years? King Charles II didn’t have any daughters, at least legitimate ones. Elizabeth, the Winter Queen, had littered Europe with princes and princesses until she’d passed away a couple of years ago—but it seemed unlikely that any Continental royalty would be visiting England during the Plague.

Comstock continued: “These persons have come here seeking refuge, as they are terrified to begin with, of the Plague and other horrors—including, but hardly limited to, a possible Dutch invasion. The violent compression of the air, which you and I might think of as a possible cure for deafness, is construed, by such people, entirely differently…”

Wilkins said something fiendishly clever and appropriate and then devoted the next couple of days to abjectly humbling himself and apologizing to every noble person within ear- and nose-shot of the late Experiments. Hooke was put to work making little wind-up toys for the two little royal girls. Meanwhile Daniel and Charles had to dismantle all of the bad-smelling experiments, and oversee their decent burials, and generally tidy things up.

It took days’ peering at Fops through hedges, deconstructing carriage-door scutcheons, and shinnying out onto the branches of diverse noble and royal family trees for Daniel to understand what Wilkins had inferred from a few of John Comstock’s pithy words and eyebrow-raisings. Comstock had formal gardens to one side of his house, which for many excellent reasons were off-limits to Natural Philosophers. Persons in French clothes strolled in them. That was not remarkable. To dally in gardens was some people’s life-work, as to shovel manure was a stable-hand’s. At a distance they all looked the same, at least to Daniel. Wilkins, much more conversant with the Court, spied on them from time to time through a prospective-glass. As a mariner, seeking to establish his bearings at night, will first look for Ursa Major, that being a constellation of exceptional size and brightness, so Wilkins would always commence his obs’v’ns. by zeroing his sights, as it were, on a particular woman who was easy to find because she was twice the size of everyone else. Many furlongs of gaily dyed fabrics went into her skirts, which shewed bravely from a distance, like French regimental standards. From time to time a man with blond hair would come out and stroll about the garden with her, moon orbiting planet. He reminded Daniel, from a distance, of Isaac.

House of Stuart

House of Orange-Nassau

Daniel did not reck who that fellow was, and was too abashed to discover his ignorance by asking, until one day a carriage arrived from London and several men in admirals’ hats climbed out of it and went to talk to the same man in the garden. Though first they all doffed those hats and bowed low.

“That blond man who walks in the garden, betimes, on the arm of the Big Dipper—would that be the Duke of York?”

“Yes,” said Wilkins—not wishing to say more, as he was breathing shallowly, his eye peeled wide open and bathed in a greenish light from the eyepiece of his prospective-glass.

“And Lord High Admiral,” Daniel continued.

“He has many titles,” Wilkins observed in a level and patient tone.

“So those chaps in the hats would be—obviously—”

“The Admiralty,” Wilkins said curtly, “or some moiety or faction thereof.” He recoiled from the scope. Daniel phant’sied he was being proffered a look-see, but only for a moment—Wilkins lifted the instrument out of the tree-crook and collapsed it. Daniel collected that he had seen something Wilkins wished he hadn’t.

The Dutch and the English were at war. Because of the Plague, this had been a desultory struggle thus far, and Daniel had forgotten about it. It was midwinter. Cold had brought the Plague to a stand. Months would pass before the weather permitted resumption of the sea-campaign. But the time to lay plans for such campaigns was now. It ought to surprise no one if the Admiralty met with the Lord High Admiral now. It would be surprising if they didn’t. What struck Daniel was that Wilkins cared that he, Daniel, had seen something. The Restoration, and Daniel’s Babylonian exile and subjugation at Cambridge, had led him to think of himself as a perfect nobody, except perhaps when it came to Natural Philosophy—and it was more obvious every day that even within the Royal Society he was nothing compared to Wren and Hooke. So why should John Wilkins give a fig whether Daniel spied a flotilla of admirals and collected, from that, that John Comstock was hosting James, Duke of York, brother of Charles II and next in line to the throne?

It must be (as Daniel realized, walking back through a defoliated orchard alongside the brooding Wilkins) because he was the son of Drake. And though Drake was a retired agitator of a defeated and downcast sect, at bay in his house on Holborn, someone was still afraid of him.

Or if not of him, then of his sect.

But the sect was shattered into a thousand claques and cabals. Cromwell was gone, Drake was too old, Gregory Bolstrood had been executed, and his son Knott was in exile—

That was it. They were afraid of Daniel.

“What is funny?” Wilkins demanded.

“People,” Daniel said, “and what goes on in their minds sometimes.”

“I say, you’re not referring to me by that—?—!”

“Oh, perish the thought. I would not mock my betters.”

“Pray, who on this estate is not your better?”

A hard question that. Daniel’s answer was silence. Wilkins seemed to find even that alarming.

“I forget you are a Phanatique born and bred.” Which was the same as saying, You recognize no man as your better, do you?

“On the contrary, I see now that you have never forgotten it.”

But something seemed to have changed in Wilkins’s mind. Like an Admiral working his ship to windward, he had suddenly come about and, after a few moments’ luffing and disarray, was now on an altogether novel tack: “The lady used to be called Anne Hyde—a close relation of John Comstock. So, far from common. Yet too common for a Duke to marry. And yet still too noble to send off to a Continental nunnery, and too fat to move far, in any case. She bore him a couple of daughters: Mary, then Anne. The Duke finally married her, though not without many complications. Since Mary or Anne could conceivably inherit the throne one day, it became a State matter. Various courtiers were talked, bribed, or threatened into coming forward and swearing on stacks of Bibles that they’d fucked Anne Hyde up and down, fucked her in the British Isles and in France, in the Low Countries and the Highlands, in the city and in the country, in ships and palaces, beds and hammocks, bushes, flower-beds, water-closets, and garrets, that they had fucked her drunk and fucked her sober, from behind and in front, from above, below, and both the right and left sides, singly and in groups, in the day and in the night and during all phases of the moon and signs of the Zodiac, whilst also intimating that any number of blacksmiths, Vagabonds, French gigolos, Jesuit provocateurs, comedians, barbers, and apprentice saddlers had been doing the same whensoever they weren’t. But despite all of this the Duke of York married her, and socked her away in St. James’s Palace, where she’s grown like one of our entomologickal prodigies in the cellar.”

Daniel had heard a good bit of this before, of course, from men who came to the house on Holborn to pay court to Drake—which gave him the odd sense that Wilkins was paying court to him. Which could not be, for Daniel had no real power or significance at all, and no prospects of getting any.

It seemed more plausible that Wilkins felt sorry for Daniel, than afraid of him; and as such was trying to shield him from those dangers that were avoidable while tutoring him in how to cope with the rest.

Which meant, if true, that Daniel ought at least to attend to the lesson that Wilkins was trying to give him. The two Princesses, Mary and Anne, would, respectively, be three and one years old now. And as their mother was related to John Comstock, it was entirely plausible that they might be visitors in the house. Which explained Comstock’s remark to Wilkins: “Two of them are all three.” Female, of tender years, and royal.

The burdensome restrictions imposed on their Natural-Philosophic researches by the host made it necessary to convene a very long Symposium in the Kitchen, where Hooke and Wilkins dictated a list (written by Daniel in a loosening hand) of experiments that were neither noisy nor smelly, but (as the evening wore on) increasingly fanciful. Hooke put Daniel to work mending his Condensing Engine, which was a piston-and-cylinder arrangement for compressing or rarefying air. He was convinced that air contained some kind of spirit that sustained both fire and life, which, when it was used up, caused both to be extinguished. So there was a whole range of experiments along the lines of: sealing up a candle and a mouse in a glass vessel, and watching to see what happened (mouse died before candle). They fixed up a huge bladder so that it was leak-proof, and put it to their mouths, and took turns breathing the same air over and over again, to see what would happen. Hooke used his engine to produce a vacuum in a large glass jar, then set a pendulum swinging in the vacuum, and set Charles there to count its swings. On the first really clear night at the onset of winter, Hooke had gone outside with a telescope and peered at Mars: he had found some light and dark patches on its surface, and ever since had been tracking their movements so that he could figure out how long it took that planet to rotate on its axis. He put Charles and Daniel to work grinding better and better lenses, or else bought them from Spinoza in Amsterdam, and they took turns looking at smaller and smaller structures on the moon. But here again, Hooke saw things Daniel didn’t. “The moon must have gravity, like the earth,” he said.

“What makes you say so?”

“The mountains and valleys have a settled shape to them—no matter how rugged the landforms, there is nothing to be seen, on that whole orb, that would fall over under gravitation. With better lenses I could measure the Angle of Repose and calculate the force of her gravity.”

“If the moon gravitates, so must everything else in the heavens,” Daniel observed.*

A long skinny package arrived from Amsterdam. Daniel opened it up, expecting to find another telescope—instead it was a straight, skinny horn, about five feet long, with helical ridges and grooves. “What is it?” he asked Wilkins.

Wilkins peered at it over his glasses and said (sounding mildly annoyed), “The horn of a unicorn.”

“But I thought that the unicorn was a mythical beast.”

“I’ve never seen one.”

“Then where do you suppose this came from?”

“How the devil should I know?” Wilkins returned. “All I know is, you can buy them in Amsterdam.”

Kings most commonly, though strong in legions, are but weak in Arguments; as they who have ever accustom’d from the Cradle to use thir will onely as thir right hand, thir reason alwayes as thir left. Whence unexpectedly constrain’d to that kind of combat, they prove but weak and puny Adversaries.

—MILTON, PREFACE TO Eikonoklastes

DANIEL GOT USED TO SEEING the Duke of York out riding and hunting with his princely friends—as much as the son of Drake could get used to such a sight. Once the hunters rode past within a bow-shot of him, near enough that he could hear the Duke talking to his companion—in French. Which gave Daniel an impulse to rush up to this French Catholic man in his French clothes, who claimed to be England’s next king, and put an end to him. He mastered it by recalling to mind the way that the Duke’s father’s head had plopped into the basket on the scaffold at the Banqueting House. Then he thought to himself: What an odd family!

Too, he could no longer muster quite the same malice towards these people. Drake had raised his sons to hate the nobility by wasting no opportunity to point out their privileges, and the way they profited from those privileges without really being aware of them. This sort of discourse had wrought extraordinarily, not only in Drake’s sons but in every Dissident meeting-house in the land, and led to Cromwell and much else; but Cromwell had made Puritans powerful, and as Daniel was now seeing, that power—as if it were a living thing with a mind of its own—was trying to pass itself on to him, which would mean that Daniel was a child of privilege too.

The tables of the Philosophical Language were finished: a vast fine-meshed net drawn through the Cosmos so that everything known, in Heaven and Earth, was trapped in one of its myriad cells. All that was needed to identify a particular thing was to give its location in the tables, which could be expressed as a series of numbers. Wilkins came up with a system for assigning names to things, so that by breaking a name up into its component syllables, one could know its location in the Tables, and hence what thing it referred to.

Wilkins drained all the blood out of a large dog and put it into a smaller dog; minutes later the smaller dog was out chasing sticks. Hooke built a new kind of clock, using the Microscope to examine some of its tiny parts. In so doing he discovered a new kind of mite living in the rags in which these parts had been wrapped. He drew pictures of them, and then performed an exhaustive three-day series of experiments to learn what would and wouldn’t kill them: the most effective killer being a Florentine poison he’d been brewing out of tobacco leaves.

Sir Robert Moray came to visit, and ground up a bit of the unicorn’s horn to make a powder, which he sprinkled in a ring, and placed a spider in the center of the ring. But the spider kept escaping. Moray pronounced the horn to be a fraud.

Wilkins hustled Daniel out of bed one night in the wee hours and took him on a dangerous nighttime hay-wain ride to the gaol in Epsom town. “Fortune has smiled on our endeavours,” Wilkins said. “The man we are going to interview was condemned to hang. But hanging crushes the parts that are of interest to us—certain delicate structures in the neck. Fortunately for us, before the hangman could get to him, he died of a bloody flux.”

“Is this going to be a new addition to the Tables, then?” Daniel asked wearily.

“Don’t be foolish—the anatomical structures in question have been known for centuries. This dead man is going to help us with the Real Character.”

“That’s the alphabet for writing down the Philosophical Language?”

“You know that perfectly well. Wake up, Daniel!”

“I ask only because it seems to me you’ve already come up with several Real Characters.”

“All more or less arbitrary. A natural philosopher on some other world, viewing a document written in those characters, would think that he were reading, not the Philosophical Language, but the Cryptonomicon! What we need is a systematic alphabet—made so that the shapes of the characters themselves provide full information as to how they are pronounced.”

These words filled Daniel with a foreboding that turned out to be fully justified: by the time the sun rose, they had fetched the dead man from the gaol, brought him back out to the cottage, and carefully cut his head off. Charles Comstock was rousted from bed and ordered to dissect the corpse, as a lesson in anatomy (and as a way of getting rid of it). Meanwhile, Hooke and Wilkins connected the head’s wind-pipe to a large set of fireplace-bellows, so that they could blow air through his voice-box. Daniel was detailed to saw off the top of the skull and get rid of the brains so that he could reach in through the back and get hold of the soft palate, tongue, and other meaty bits responsible for making sounds. With Daniel thus acting as a sort of meat puppeteer, and Hooke manipulating the lips and nostrils, and Wilkins plying the bellows, they were able to make the head speak. When his speaking-parts were squished into one configuration he made a very clear “O” sound, which Daniel (very tired now) found just a bit unsettling. Wilkins wrote down an O-shaped character, reflecting the shape of the man’s lips. This experiment went on all day, Wilkins reminding the others, when they showed signs of tiredness, that this rare head wouldn’t keep forever—as if that weren’t already obvious. They made the head utter thirty-four different sounds. For each one of them, Wilkins drew out a letter that was a sort of quick freehand sketch of the positions of lips, tongue, and other bits responsible for making that noise. Finally they turned the head over to Charles Comstock, to continue his anatomy-lesson, and Daniel went to bed for a series of rich nightmares.

Looking at Mars had put Hooke in mind of cœlestial affairs; for that reason he set out with Daniel one morning in a wagon, with a chest of equipment. This must have been important, because Hooke packed it himself, and wouldn’t let anyone else near it. Wilkins kept trying to persuade them to use the giant wheel, instead of borrowing one of John Comstock’s wagons (and further wearing out their welcome). Wilkins claimed that the giant wheel, propelled by the youthful and vigorous Daniel Waterhouse, could (in theory) traverse fields, bogs, and reasonably shallow bodies of water with equal ease, so they could simply travel in a perfectly straight line to their destination, instead of having to follow roads. Hooke declined, and chose the wagon.

They traveled for several hours to a certain well, said to be more than three hundred feet deep, bored down through solid chalk. Hooke’s mere appearance was enough to chase away the local farmers, who were only loitering and drinking anyway. He got Daniel busy constructing a solid, level platform over the mouth of the well. Hooke meanwhile took out his best scale and began to clean and calibrate it. He explained, “For the sake of argument, suppose it really is true that planets are kept in their orbits, not by vortices in the æther, but by the force of gravity.”

“Yes?”

“Then, if you do some mathematicks, you can see that it simply would not work unless the force of gravity got weaker, as the distance from the center of attraction increased.”

“So the weight of an object should diminish as it rises?”

“And increase as it descends,” Hooke said, nodding significantly at the well.

“Aha! So the experiment is to weigh something here at the surface, and then to…” and here Daniel stopped, horror-stricken.

Hooke twisted his bent neck around and peered at him curiously. Then, for the first time since Daniel had met him, he laughed out loud. “You’re afraid that I’m proposing to lower you, Daniel Waterhouse, three hundred feet down into the bottom of this well, with a scale in your lap, to weigh something? And that once down there the rope will break?” More laughing. “You need to think more carefully about what I said.”

“Of course—it wouldn’t work that way,” Daniel said, deeply embarrassed on more than one level.

“And why not?” Hooke asked, Socratically.

“Because the scale works by balancing weights on one pan against the object to be weighed, on the other…and if it’s true that all objects are heavier at the bottom of the well, then both the object, and the weights, will be heavier by the same amount…and so the result will be the same, and will teach us nothing.”

“Help me measure out three hundred feet of thread,” Hooke said, no longer amused.

They did it by pulling the thread off a reel, and stretching it alongside a one-fathom-long rod, and counting off fifty fathoms. One end of the thread Hooke tied to a heavy brass slug. He set the scale up on the platform that Daniel had improvised over the mouth of the well, and put the slug, along with its long bundle of thread, on the pan. He weighed the slug and thread carefully—a seemingly endless procedure disturbed over and over by light gusts of wind. To get a reliable measurement, they had to devote a couple of hours to setting up a canvas wind-screen. Then Hooke spent another half hour peering at the scale’s needle through a magnifying lens while adding or subtracting bits of gold foil, no heavier than snowflakes. Every change caused the scale to teeter back and forth for several minutes before settling into a new position. Finally, Hooke called out a weight in pounds, ounces, grains, and fractions of grains, and Daniel noted it down. Then Hooke tied the free end of the thread to a little eye he had screwed to the bottom of the pan, and he and Daniel took turns lowering the weight into the well, letting it drop a few inches at a time—if it got to swinging, and scraped against the chalky sides of the hole, it would pick up a bit of extra weight, and ruin the experiment. When all three hundred feet had been let out, Hooke went for a stroll, because the weight was swinging a little bit, and its movements would disturb the scale. Finally it settled down enough that he could go back to work with his magnifying glass and his tweezers.

Daniel, in other words, had a lot of time to think that day. Cells, spiders’ eyes, unicorns’ horns, compressed and rarefied air, dramatic cures for deafness, philosophical languages, and flying chariots were all perfectly fine subjects, but lately Hooke’s interest had been straying into matters cœlestial, and that made Daniel think about his roommate. Just as certain self-styled philosophers in minor European courts were frantic to know what Hooke and Wilkins were up to at Epsom, so Daniel wanted only to know what Isaac was doing up at Woolsthorpe.

“It weighs the same,” Hooke finally pronounced, “three hundred feet of altitude makes no measurable difference.” That was the signal to pack up all the apparatus and let the farmers draw their water again.

“This proves nothing,” Hooke said as they rode home through the dark. “The scale is not precise enough. But if one were to construct a clock, driven by a pendulum, in a sealed glass vessel, so that changes in moisture and baroscopic pressure would not affect its speed…and if one were to run that clock in the bottom of a well for a long period of time…any difference in the pendulum’s weight would be manifest as a slowing, or quickening, of the clock.”

“But how would you know that it was running slow or fast?” Daniel asked. “You’d have to compare it against another clock.”

“Or against the rotation of the earth,” Hooke said. But it seemed that Daniel’s question had thrown him into a dark mood, and he said nothing more until they had reached Epsom, after midnight.

THE TEMPERATURE AT NIGHT began to fall below freezing, and so it was time to calibrate thermometers. Daniel and Charles and Hooke had been making them for some weeks out of yard-long glass tubes, filled with spirits of wine, dyed with cochineal. But they had no markings on them. On cold nights they would bundle themselves up and immerse those thermometers in tubs of distilled water and then sit there for hours, giving the tubs an occasional stir, and waiting. When the water froze, if they listened carefully enough, they could hear a faint searing, splintering noise come out of the tub as flakes of ice shot across the surface—then they’d rouse themselves into action, using diamonds to make a neat scratch on each tube, marking the position of the red fluid inside.

Hooke kept a square of black velvet outside so that it would stay cold. When it snowed during the daytime, he would take his microscope outside and spread the velvet out on the stage and peer at any snowflakes that happened to fall on it. Daniel saw, as Hooke did, that each one was unique. But again Hooke saw something Daniel missed: “in any particular snowflake, all six arms are the same—why does this happen? Why shouldn’t each of the six arms develop in a different and unique shape?”

“Some central organizing principle must be at work, but—?” Daniel said.

“That is too obvious to even bother pointing out,” Hooke said. “With better lenses, we could peer into the core of a snowflake and discover that principle at work.”

A week later, Hooke opened up the thorax of a live dog and removed all of its ribs to expose the beating heart. But the lungs had gone flaccid and did not seem to be doing their job.

The screaming sounded almost human. A man with an expensive voice came down from John Comstock’s house to enquire about it. Daniel, too bleary-eyed to see clearly and too weary to think, took him for a head butler or something. “I shall write an explanation, and a note of apology to him,” Daniel mumbled, looking about for a quill, rubbing his blood-sticky hand on his breeches.

“To whom, prithee? asked the butler, amused. Though he seemed young for a head-butler. In his early thirties. He was in a linen night-dress. His scalp glistered with a fine carpet of blond stubble, the mark of a man who always wore a periwig.

“The Earl of Epsom.”

“Why not write it to the Duke of York?”

“Very well then, I’ll write it to him.”

“Then why not dispense with writing altogether and simply tell me what the hell you are doing?”

Daniel took this for insolence until he looked the visitor in the face and realized it was the Duke of York in person.

He really ought to bow, or something. Instead of which he jerked. The Duke made a gesture with his hand that seemed to mean that the jerk was accepted as due obeisance and could they please get on with the conversation now.

“The Royal Society—” Daniel began, thrusting that word Royal out in front of him like a shield, “has brought a dead dog to life with another’s blood, and has now embarked on a study of artificial breath.”

“My brother is fond of your Society,” said James, “or his Society I should say, for he made it Royal.” This, Daniel suspected, was to explain why he was not going to have them all horsewhipped. “I do wonder at the noise. Is it expected to continue all night?”

“On the contrary, it has already ceased,” Daniel pointed out.

The Lord High Admiral preceded him into the kitchen, where Hooke and Wilkins had thrust a brass pipe down the dog’s windpipe and connected it to the same trusty pair of bellows they’d used to make the dead man’s head speak. “By pumping the bellows they were able to inflate and deflate the lungs, and prevent the dog from asphyxiating,” explained Charles Comstock, after the experimenters had bowed to the Duke. “Now it only remains to be seen how long the animal can be kept alive in this way. Mr. Waterhouse and I shall spell each other at the bellows until Mr. Hooke pronounces an end to the experiment.”

At the mention of Daniel’s family name, the Duke flicked his eyes towards him for a moment.

“If it must suffer in the name of your inquiry, thank Heaven it does so quietly,” the Duke remarked, and turned to leave. The others would follow; but the Duke stopped them with a “Do carry on, as you were.” But to Daniel he said, “A word, if you please, Mr. Waterhouse,” and so Daniel escorted him out onto the lawn half wondering whether he was about to be carved up worse than the dog.

A few moments previously, he’d mastered a daft impulse to tackle his royal highness before his royal highness reached the kitchen, for fear that his royal highness would be disgusted by what was going on in there. But he’d not reckoned on the fact that the Duke, young though he was, had fought in a lot of battles, both at sea and on land. Which was to say that as bad as this business with the dog was, the Duke of York had seen much worse done to humans. The R.S., far from seeming like a band of mad ruthless butchers, were dilettantes by his standards. Further grounds (as if any were wanted!) for Daniel to feel queasy.

Daniel really knew of no way to regulate his actions other than to be rational. Princes were taught a thing or two about being rational, as they were taught to play a little lute and dance a passable ricercar. But what drove their actions was their own force of will; in the end they did as they pleased, rational or not. Daniel had liked to tell himself that rational thought led to better actions than brute force of will; yet here was the Duke of York all but rolling his eyes at them and their experiment, seeing naught that was new.

“A friend of mine brought back something nasty from France,” his royal highness announced.

It took Daniel a long time to decrypt this. He tried to understand it in any number of different ways, but suddenly the knowledge rumbled through his mind like a peal of thunder through a coppice. The Duke had said: I have syphilis.

“Shame, that,” Daniel said. For he was not sure, yet, that he had translated it correctly. He must be ever so careful and vague lest this conversation degenerate into a comedy of errors ending with his death by rapier-thrust.

“Some are of the opinion that mercury cures it.”

“It is also a poison, though,” Daniel said.

Which was common knowledge; but it seemed to confirm, in the mind of James Stuart, Duke of York and Lord High Admiral, that he was talking to just the right chap. “Surely with so many clever Doctors in the Royal Society, working on artificial breath and such, there must be some thought of how to cure a man such as my friend.”

And his wife and his children, Daniel thought, for James must have either gotten it from, or passed it on to, Anne Hyde, who had therefore probably given it to the daughters, Mary and Anne. To date, James’s older brother the King had not been able to produce any legitimate children. There were plenty of bastards like Monmouth. But none eligible to inherit the throne. And so this nasty thing that James had brought back from France was really a matter of whether the Stuart dynasty was to survive.

This raised a fascinating side question. With a whole cottage full of Royal Society Fellows to choose from, why had James carefully chosen to speak with the one who happened to be the son of a Phanatique?

“It is a sensitive matter,” the Duke remarked, “the sort of thing that stains a man’s honor, if it is bandied about.”

Daniel readily translated this as follows: If you tell anyone, I’ll send someone round to engage you in a duel. Not that anyone would pay any notice, anyway, if the son of Drake were to level an accusation of moral turpitude against the Duke of York. Drake had been doing such things without letup for fifty years. And so the Duke’s strategy was now plain to Daniel: he had chosen Daniel to hear about his syphilis because if Daniel were so foolish as to spread rumors, no one would hear them above the roar of obloquy produced at all times by Drake. In any case, Daniel would not be able to keep it up for very long before he was found in a field outside of London with a lot of rapier wounds in his body.

“You will let me know, won’t you, if the Royal Society learns anything on this front?” said James, making to leave.

“So that you can pass the information on to your friend? Of course,” Daniel said. Which was the end of that conversation. He returned to the kitchen to get an idea of how much longer the experiment was going to go on.

The answer: longer than any of them really wanted. By the time they were finished, dawn-light was beginning to come in the windows, giving them a premonition of just how ghastly the kitchen was going to look when the sun actually rose. Hooke was sitting crookedly in a chair, shocked and morose, appalled by himself, and Wilkins was hunched forward supporting his head on a smeared fist.

They’d come here supposedly as refugees from the Black Death, but really they were fleeing their own ignorance—they hungered for understanding, and were like starving wretches who had broken into a lord’s house and gone on an orgy of gluttonous feasting, wolfing down new meals before they could digest, or even chew, the old ones. It had lasted for the better part of a year, but now, as the sun rose over the aftermath of the artificial breath experiment, they were scattered around, blinking stupidly at the devastated kitchen, with its dog-ribs strewn all over the floor, and huge jars of preserved spleens and gall-bladders, specimens of exotic parasites nailed to planks or glued to panes of glass, vile poisons bubbling over on the fire, and suddenly they felt completely disgusted with themselves.

Daniel gathered the dog’s remains up in his arms—messy, but it scarcely mattered—all their clothes would have to be burned anyway—and walked out to the bone-yard on the east side of the cottage, where the remains of all Hooke’s and Wilkins’s investigations were burned, buried, or used to study the spontaneous generation of flies. Notwithstanding which, the air was relatively clean and fresh out here. Having set the remains down, Daniel found that he was walking directly towards a blazing planet, a few degrees above the western horizon, which could only be Venus. He walked and walked, letting the dew on the grass cleanse the blood from his shoes. The dawn was making the fields shimmer pink and green.

Isaac had sent him a letter: “Require asst. w/obs. of Venus pls. come if you can.” He had wondered at the time if this might be something veiled. But standing there in that dew-silvered field with his back to the house of carnage and nothing before him but the Dawn Star, Daniel remembered what Isaac had said years ago about the natural harmony between the heavenly orbs and the orbs we view them with. Four hours later he was riding north on a borrowed horse.