Royal Society Meeting, Gresham’s College

12 AUGUST 1670

This Club of Vertuoso’s, upon a full Night, when some eminent Maggot-monger, for the Satisfaction of the Society, had appointed to demonstrate the Force of Air, by some hermetical Pot gun, to shew the Difference of the Gravity between the Smoak of Tobacco and that of Colts-foot and Bittany, or to try some other such like Experiment, were always compos’d of such an odd Mixture of Mankind, that, like a Society of Ringers at a quarterly Feast, here sat a fat purblind Philosopher next to a talkative Spectacle-maker; yonder a half-witted Whim of Quality, next to a ragged Mathematician; on the other Side a consumptive Astronomer next to a water-gruel Physician; above them, a Transmutator of Metals, next to a Philosopher-Stone-Hunter; at the lower End, a prating Engineer, next to a clumsy-fisted Mason; at the upper End of all, perhaps, an Atheistical Chymist, next to a whimsy-headed Lecturer; and these the learned of the Wise-akers wedg’d here and there with quaint Artificers, and noisy Operators, in all Faculties; some bending beneath the Load of Years and indefatigable Labour, some as thin-jaw’d and heavyey’d, with abstemious Living and nocturnal Study as if, like Pharaoh’s Lean Kine, they were designed by Heaven to warn the World of a Famine; others looking as wild, and disporting themselves as frenzically, as if the Disappointment of their Projects had made them subject to a Lunacy. When they were thus met, happy was the Man that could find out a new Star in the Firmament; discover a wry Step in the Sun’s Progress; assign new Reasons for the Spots of the Moon, or add one Stick to the Bundle of Faggots which have been so long burthensome to the back of her old Companion; or, indeed, impart any crooked Secret to the learned Society, that might puzzle their Brains, and disturb their Rest for a Month afterwards, in consulting upon their Pillows how to straiten the Project, that it might appear upright to the Eye of Reason, and the knotty Difficulty to be rectify’d, as to bring Honour to themselves, and Advantage to the Public.

—NED WARD, The Vertuoso’s Club

AUGUST 12. AT A MEETING of the SOCIETY,

MR. NICHOLAS MERCATOR and MR. JOHN LOCKE were elected and admitted.

The rest of Mr. BOYLE’s experiments about light were read, with great satisfaction to the society; who ordered, that all should be registered, and that Mr. HOOKE should take care of having the like experiments tried before the society, as soon as he could procure any shining rotten wood or fish.

Dr. CROUNE brought in a dead parakeet.

Sir JOHN FINCH displayed an asbestos hat-band.

Dr. ENT speculated as to why it is hotter in summer than winter.

Mr. POWELL offered to be employed by the society in any capacity whatever.

Mr. OLDENBURG being absent, Mr. WATERHOUSE read a letter from a PORTUGUESE nobleman, most civilly complimenting the society for its successes in removing the spleens of dogs, without ill effect; and going on to enquire, whether the society might undertake to perform the like operation on his Wife, as she was most afflicted with splenetic distempers.

Dr. ENT was put in mind of an account concerning oysters.

Mr. HOOKE displayed an invention for testing whether a surface is level, consisting of a bubble of air trapped in a sealed glass tube, otherwise filled with water.

The Dog, that had a piece of his skin cut off at the former meeting, being enquired after, and the operator answering, that he had run away, it was ordered, that another should be provided against the next meeting for the grafting experiment.

The president produced from Sir WILLIAM CURTIUS a hairy ball found in the belly of a cow.

THE DUKE OF GUNFLEET produced a letter of Mons. HUYGENS, dated at Paris, mentioning a new observation concerning Saturn, made last spring at Rome by one CAMPANI, viz. that the circle of Saturn had been seen to cast a shadow on the sphere: which observation Mons. HUYGENS looked on as confirming his hypothesis, that Saturn is surrounded by a Ring.

A Vagabond presented himself, who had formerly received a shot into his belly, breaking his guts in two: whereupon one end of the colon stood out at the left side of his belly, whereby he voided all his excrement, which he did for the society.

Mr. POVEY presented a skeleton to the society.

Mr. BOYLE reported that swallows live under frozen water in the Baltic.

Dr. GODDARD mentioned that wainscotted rooms make cracking noises in mornings and evenings.

Mr. WALLER mentioned that toads come out in moist cool weather.

Mr. HOOKE related, that he had found the stars in Orion’s belt, which Mons. HUYGENS made but three, to be five.

Dr. MERRET produced a paper, wherein he mentioned, that three skulls with the hair on and brains in them were lately found at Black-friars in pewter vessels in the midst of a thick stone-wall, with certain obscure inscriptions. This paper was ordered to be registered.

Mr. HOOKE made an experiment to discover, whether a piece of steel first counterpoised in exact scales, and then touched by a vigorous magnet, acquires thereby any sensible increase in weight. The event was, that it did not.

Dr. ALLEN gave an account of a person, who had lately lost a quantity of his brain, and yet lived and was well.

Dr. WILKINS presented the society with his book, intitled, An Essay Towards a Real Character and Philosophical Language.

Mr. HOOKE suggested, that it was worth inquiry, whether there were any valves in plants, which he conceived to be very necessary for the conveying of the juices of trees up to the height of sometimes 200, 300, and more feet; which he saw not how it was possible to be performed without valves as well as motion.

Sir ROBERT SOUTHWELL presented for the repository a skull of an executed person with the moss grown on it in Ireland.

THE BISHOP OF CHESTER moved, that Mr. HOOKE might be ordered to try, whether he could by means of the microscopic moss-seed formerly shewn by him, make moss grow on a dead man’s skull.

Mr. HOOKE intimated that the experiment proposed by THE BISHOP OF CHESTER would not be as productive of new Knowledge, as a great many others that could be mentioned, if there were time enough to mention them all.

Mr. OLDENBURG being absent, Mr. WATERHOUSE read an extract, which the former had received from Paris, signifying that it was most certain, that Dr. DE GRAAF had unravelled testicles, and that one of them was kept by him in spirit of wine. Some of the physicians present intimating, that the like had been attempted in England many years before, but not with that success, that they could yet believe what Dr. DE GRAAF affirmed.

THE DUKE OF GUNFLEET gave of Dr. DE GRAAF an excellent Character; attesting that, while at Paris, this same Doctor had cured the Duke’s son (now the EARL OF UPNOR) of the bite of a venomous spyder.

Occasion being given to speak of tarantulas, some of the members said, that persons bitten by them, though cured, yet must dance once a year: others, that different patients required different airs to make them dance, according to the different sorts of tarantulas which had bitten them.

THE DUKE OF GUNFLEET said, that the Spyder that had bitten his son in Paris, was not of the tarantula sort, and accordingly that the Earl does not under any account suffer any compulsion to dance.

The society gave order for the making of portable barometers, contrived by Mr. BOYLE, to be sent into several parts of the world, not only into the most distant places of England, but likewise by sea into the East and West Indies, and other parts, particularly to the English plantations in Bermuda, Jamaica, Barbados, Virginia, and New England; and to Tangier, Moscow, St. Helena, the Cape of Good Hope, and Scanderoon.

Dr. KING was put in mind of dissecting a lobster and an oyster.

Mr. HOOKE produced some plano-convex spherical glasses, as small as pin-heads, to serve for object-glasses in microscopes. He was desired to put some of them into the society’s great microscope for a trial.

THE DUKE OF GUNFLEET produced the skin of a Moor tanned.

Mr. BOYLE remarked, that two very able physicians of his acquaintance gave to a woman desperately sick of the iliac passion above a pound of crude quicksilver which remained several days in her body without producing any fatal symptom; and afterwards dissecting the dead corpse, they found, that part of her gut, where the excrement was stopped, gangrened; but the quicksilver lay all on a heap above it, and had not so much as discoloured the parts of the gut contiguous to it.

Mr. HOOKE was put in mind of an experiment of making a body heavier than gold, by putting quicksilver to it, to see, whether any of it would penetrate into the pores of gold.

Dr. CLARKE proposed, that a man hanged might be begged of the King, to try to revive him; and that in case he were revived, he might have his life granted him.

Mr. WATERHOUSE produced a new telescope, invented by Mr. Isaac NEWTON, professor of mathematics in the university of Cambridge, improving on previous telescopes by contracting the optical path. THE DUKE OF GUNFLEET, Dr. CHRISTOPHER WREN, and Mr. HOOKE, examining it, had so good opinion of it, that they proposed it be shown to the King, and that a description and scheme of it should be sent to Mons. HUYGENS at Paris, thereby to secure this invention to Mr. NEWTON.

The experiment of the opening of the thorax of a dog was suggested. Mr. HOOKE and Mr. WATERHOUSE having made this experiment formerly, begged to be excused for the duration of any such proceedings. Dr. BALLE and Dr. KING made the experiment but did not succeed.

A fifth Cabal, perhaps, would be a Knot of Mathematicians, who would sit so long wrangling about squaring the Circle, till, with Drinking and Rattling, they were ready to let fall a nauseous Perpendicular from their Mouths to the Chamber-Pot. Another little Party would be deeply engaged in a learned Dispute about Transmutation of Metals, and contend so warmly about turning Lead into Gold, till the Bar had a just Claim to all the Silver in their Pockets…

—NED WARD, The Vertuoso’s Club

A FEW OF THEM ENDED UP at a tavern, unfortunately called the Dogg, on Broad Street near London Wall. Wilkins (who was the Bishop of Chester now) and Sir Winston Churchill and Thomas More Anglesey, a.k.a. the Duke of Gunfleet, amused themselves using Newton’s telescope to peer into the windows of the Navy Treasury across the way, where lamps were burning and clerks were working late. Wheelbarrows laden with lockboxes were coming up every few minutes from the goldsmiths’ shops on Thread-needle.

Hooke commandeered a small table, set his bubble-level upon it, and began to adjust it by inserting scraps of paper beneath its legs. Daniel quaffed bitters and thought that this was all a great improvement on this morning.

“To Oldenburg,” someone said, and even Hooke raised his head up on its bent neck and drank to the Secretary’s health.

“Are we allowed to know why the King put him in the Tower?” asked Daniel.

Hooke suddenly became absorbed in table-levelling, the others in viewing a planet that was rising over Bishopsgate, and Daniel reckoned that the reason for Oldenburg’s imprisonment was one of those things that everyone in London should simply know, it was one of those facts Londoners breathed in like the smoke of sea-coal.

John Wilkins brushed significantly past Daniel and stepped outside, plucking a pipe from a tobacco-box on the wall. Daniel joined him for a smoke on the street. It was a fine summer eve in Bishopsgate: on the far side of London Wall, lunaticks at Bedlam were carrying on vigorous disputes with angels, demons, or the spirits of departed relations, and on this side, the rhythmic yelping of a bone-saw came through a half-open window of Gresham’s College as a cabal of Bishops, Knights, Doctors, and Colonels removed the rib-cage from a living mongrel. The Dogg’s sign creaked above in a mild river-breeze. Coins clinked dimly inside the Navy’s lockboxes as porters worried them up stairs. Through an open window they could occasionally glimpse Samuel Pepys, Fellow of the Royal Society, making arrangements with his staff and gazing out the window, longingly, at the Dogg. Daniel and the Bishop stood there and took it in for a minute as a sort of ritual, as Papists cross themselves when entering a church: to do proper respect to the place.

“Mr. Oldenburg is the heart of the R.S.,” Bishop Wilkins began.

“I would give that honor to you, or perhaps Mr. Hooke…”

“Hold—I was not finished—I was launching a metaphor. Please remember that I’ve been preaching to rapt congregations, or at least they are pretending to be rapt—in any case, they sit quietly while I develop my metaphors.”

“I beg forgiveness, and am now pretending to be rapt.”

“Very well. Now! As we have learned by doing appalling things to stray dogs, the heart accepts blood returning from organs, such as the brain, through veins, such as the jugular. It expels blood toward these organs through arteries, such as the carotid. Do you remember what happened when Mr. Hooke cross-plumbed the mastiff, and connected his jugular to his carotid? And don’t tell me that the splice broke and sprayed blood all around—this I remember.”

“The blood settled into a condition of equilibrium, and began to coagulate in the tube.”

“And from this we concluded that—?”

“I have long since forgotten. That bypassing the heart is a bad idea?”

“One might conclude,” said the Bishop helpfully, “that an inert vessel, that merely accepts the circulating Fluid, but never expels it, becomes a stagnant back-water—or to put it otherwise, that the heart, by forcing it outwards, drives it around the cycle that in good time brings it back in from the organs and extremities. Hallo, Mr. Pepys!” (Shifting his focus to across the way.) “Starting a war, are we?”

“Too easy…winding one up, my lord,” from the window.

“Is it going to be finished any time soon? Your diligence is setting an example for all of us—stop it!”

“I detect the beginnings of a lull…”

“Now, Daniel, anyone who scans the History of the Royal Society can see that, at each meeting, Mr. Oldenburg reads several letters from Continental savants, such as Mr. Huygens, and, lately, Dr. Leibniz…”

“I’m not familiar with that name.”

“You will be—he is a mad letter-writer and a protégé of Huygens—a devotee of Pansophism—he has lately been smothering us with curious documents. You haven’t heard about him because Mr. Oldenburg has been passing his missives round to Mr. Hooke, Mr. Boyle, Mr. Barrow, and others, trying to find someone who can even read them, as a first step towards determining whether or not they are nonsense. But I digress. For every letter Mr. Oldenburg reads, he receives a dozen—why so many?”

“Because, like a heart, he pumps so many outwards—?”

“Yes, precisely. Whole sacks of them crossing the Channel—driving the circulation that brings new ideas, from the Continent, back to our little meetings.”

“Damn me, and now the King’s clapped him in the Tower!” said Daniel, unable to avoid feeling a touch melodramatic—this kind of dialog not being, exactly, his metier.

“Bypassing the heart,” said Wilkins, without a trace of any such self-consciousness. “I can already feel the Royal Society coagulating. Thank you for bringing Mr. Newton’s telescope. Fresh blood! When can we see him at a meeting?”

“Probably never, as long as the Fellows persist in cutting up dogs.”

“Ah—he’s squeamish—abhors cruelty?”

“Cruelty to animals.”

“Some Fellows have proposed that we borrow residents of…” said the Bishop, nodding towards Bedlam.

“Isaac might be more comfortable with that,” Daniel admitted.

A barmaid had been hovering, and now stepped into the awkward silence: “Mr. Hooke requests your presence.”

“Thank God,” Wilkins said to her, “I was afraid you were going to complain he had committed an offense against your person.”

The patrons of the Dogg were backed up against the walls in the configuration normally used for watching bar-fights, viz. forming an empty circle around Mr. Hooke’s table, which was (as shown by the bubble instrument) now perfectly level. It was also clean, and empty except for a glob of quicksilver in the middle, with numerous pinhead-sized droplets scattered about in novel constellations. Mr. Hooke was peering at the large glob—a perfect, regular dome—through an optical device of his own manufacture. Glancing up, he twiddled a hog-bristle between thumb and index finger, pushing an invisibly tiny droplet of mercury across the table until it merged with the large one. Then more peering. Then, moving with the stealth of a cat-burglar, he backed away from the table. When he had put a good fathom between himself and the experiment, he looked up at Wilkins and said, “Universal Measure!”

“What!? Sir! You don’t say!”

“You will agree,” Hooke said, “that level is an absolute concept—any sentient person can make a surface level.”

“It is in the Philosophical Language,” said Bishop Wilkins—this signified yes.

Pepys came in the door, looking splendid, and had his mouth open to demand beer, when he realized a solemn ceremony was underway.

“Likewise mercury is the same in all places—in all worlds.”

“Agreed.”

“As is the number two.”

“Of course.”

“Here I have created a flat, clean, smooth, level surface. On it I have placed a drop of mercury and adjusted it so that the diameter is exactly two times its height. Anyone, anywhere could repeat these steps—the result would be a drop of mercury exactly the same size as this one. The diameter of the drop, then, can be used as the common unit of measurement for the Philosophical Language!”

The sound of men thinking.

Pepys: “Then you could build a container that was a certain number of those units high, wide, and deep; fill it with water; and have a standard measure of weight.”

“Just so, Mr. Pepys.”

“From length and weight you could make a standard pendulum—the time of its alternations would provide a universal unit of time!”

“But water beads up differently on different surfaces,” said the Bishop of Chester. “I assume the same sorts of variations occur with mercury.”

Hooke, resentful: “The surface to be used could be stipulated: copper, or glass…”

“If the force of gravity varies with altitude, how would that affect the height of the drop?” asked Daniel Waterhouse.

“Do it at sea-level,” said Hooke, with a dollop of spleen.

“Sea-level varies with the tides,” Pepys pointed out.

“What of other planets?” Wilkins demanded thunderously.

“Other planets!? We haven’t finished with this one!”

“As our compatriot Mr. Oldenburg has said: ‘You will please to remember that we have taken to task the whole Universe, and that we were obliged to do so by the nature of our Design!’ ”

Hooke, very stormy-looking now, scraped most of the quicksilver into a funnel, and thence into a flask; departed; and was sighted by Mr. Pepys (peering through the Newtonian reflector) no more than a minute later, stalking off towards Hounsditch in the company of a whore. “He’s flown into one of his Fits of Melancholy—we won’t see him for two weeks now—then we’ll have to reprimand him,” Wilkins grumbled.

Almost as if it were written down somewhere in the Universal Character, Pepys and Wilkins and Waterhouse somehow knew that they had unfinished business together—that they ought to be having a discreet chat about Mr. Oldenburg. A triangular commerce in highly significant glances and eyebrow-raisings flourished there in the Dogg, for the next hour, among them. But they could not all break free at once: Churchill and others wanted more details from Daniel about this Mr. Newton and his telescope. The Duke of Gun-fleet got Pepys cornered, and interrogated him about dark matters concerning the Navy’s finances. Blood-spattered, dejected Royal Society members stumbled in from Gresham’s College, with the news that Drs. King and Belle had gotten lost in the wilderness of canine anatomy, the dog had died, and they really needed Hooke—where was he? Then they cornered Bishop Wilkins and talked Royal Society politics—would Comstock stand for election to President again? Would Anglesey arrange to have himself nominated?

BUT LATER—too late for Daniel, who had risen early, when Isaac had—the three of them were together in Pepys’s coach, going somewhere.

“I note my Lord Gunfleet has taken up a sudden interest in Naval-gazing,” said Wilkins.

“As our safety from the Dutch depends upon our Navy,” Pepys said carefully, “and most of our Navy is arrayed before the Casbah in Algiers, many Persons of Quality share Anglesey’s curiosity.”

Wilkins only looked amused. “I did not hear him asking you of frigates and cannons,” he said, “but of Bills of Exchange, and pay-coupons.”

Pepys cleared his throat at length, and glanced nervously at Daniel. “Those who are responsible for draining the Navy’s coffers, must answer to those who are responsible for filling them,” he finally said.

Even Daniel, a dull Cambridge scholar, had the wit to know that the coffer-drainer being referred to here was the armaments-maker John Comstock, Earl of Epsom—and that the coffer-filler was Thomas More Anglesey, Duke of Gunfleet, and father of Louis Anglesey, the Earl of Upnor.

“Thus C and A,” Wilkins said. “What does the Cabal’s second syllable have to say of Naval matters?”

“No surprises from Bolstrood* of course.”

“Some say Bolstrood wants our Navy in Africa, so that the Dutch can invade us, and make of us a Calvinist nation.”

“Given that the V.O.C.† is paying out dividends of forty percent, I think that there are many new Calvinists on Threadneedle Street.”

“Is Apthorp one of them?”

“Those rumors are nonsense—Apthorp would rather build his East India Company, than invest in the Dutch one.”

“So it follows that Apthorp wants a strong Navy, to protect our merchant ships from those Dutch East Indiamen, so topheavy with cannons.”

“Yes.”

“What of General Lewis?”

“Let’s ask the young scholar,” Pepys said mischievously.

Daniel was dumbstruck for a few moments—to the gurgling, boyish amusement of Pepys and Wilkins.

The telescope seemed to be watching Daniel, too: it sat in its box across from him, a disembodied sensory organ belonging to Isaac Newton, staring at him with more than human acuteness. He heard Isaac demanding to know what on earth he, Daniel Waterhouse, could possibly be doing, riding across London in Samuel Pepys’s coach—pretending to be a man of affairs!

“Err…a weak Navy forces us to keep a strong Army, to fight off any Dutch invasions,” Daniel said, thinking aloud.

“But with a strong Navy, we can invade the Hollanders!” Wilkins protested. “More glory for General Lewis, Duke of Tweed!”

“Not without French help,” Daniel said, after a few moments’ consideration, “and my lord Tweed is too much the Presbyterian.”

“Is this the same good Presbyterian who enjoyed a secret earldom at the exile court at St. Germaines, when Cromwell ruled the land?”

“He is a Royalist, that’s all,” Daniel demurred.

What was he doing in this carriage having this conversation, besides going out on a limb, and making a fool of himself? The real answer was known only to John Wilkins, Lord Bishop of Chester, Author of both the Cryptonomicon and the Philosophical Language, who encrypted with his left hand and made things known to all possible worlds with his right. Who’d gotten Daniel into Trinity College—invited him out to Epsom during the Plague—nominated him for the Royal Society—and now, it seemed, had something else in mind for him. Was Daniel here as an apprentice, sitting at the master’s knee? It was shockingly prideful, and radically non-Puritan, for him to think so—but he could come up with no other hypothesis.

“Right, then, it all has to do with Mr. Oldenburg’s letters abroad…” Pepys said, when some change in the baroscopic pressure (or something) signified it was time to drop pretenses and talk seriously.

Wilkins: “I assumed that. Which one?”

“Does it matter? All of the GRUBENDOL letters are intercepted and read before he even sees them.”

“I’ve always wondered who does the reading,” Wilkins reflected. “He must be very bright, or else perpetually confused.”

“Likewise, all of Oldenburg’s outgoing mail is examined—you knew this.”

“And in some letter, he said something indiscreet—?”

“It is simply that the sheer volume of his foreign correspondence—taken together with the fact that he’s from Germany—and that he’s worked as a diplomat on the Continent—and that he’s a friend of Cromwell’s Puritanickal poet—”

“John Milton.”

“Yes…finally, consider that no one at court understands even a tenth of what he’s saying in his letters—it makes a certain type of person nervous.”

“Are you saying he was thrown into the Tower of London on general principles?”

“As a precaution, yes.”

“What—does that mean he has to stay in there for the rest of his life?”

“Of course not…only until certain very tender negotiations are finished.”

“Tender negotiations…” Wilkins repeated a few times, as if further information could thus be pounded out of the dry and pithy words.

And here the discourse, which, to Daniel, had been merely confusing up to this point, plunged into obscurity perfect and absolute.

“I didn’t know he had a tender bone in his body…oh, wipe that smirk off your face, Mr. Pepys, I meant nothing of the sort!”

“Oh, it is known that his feelings for sa soeur are most affectionate. He’s writing letters to her all the time lately.”

“Does she write back?”

“Minette spews out letters like a diplomat.”

“Keeping his hisness well acquainted—I am guessing—with all that is new with her beloved?”

“The volume of correspondence is such,” Pepys exclaimed, “that His Majesty can never have been so close to the man you refer to as he is today. Hoops of gold are stronger than bands of steel.”

Wilkins, starting to look a bit queasy: “Hmmm…a good thing, then, isn’t it, that formal contacts are being made through those two arch-Protestants—”

“I would refer you to Chapter Ten of your 1641 work,” said Pepys.

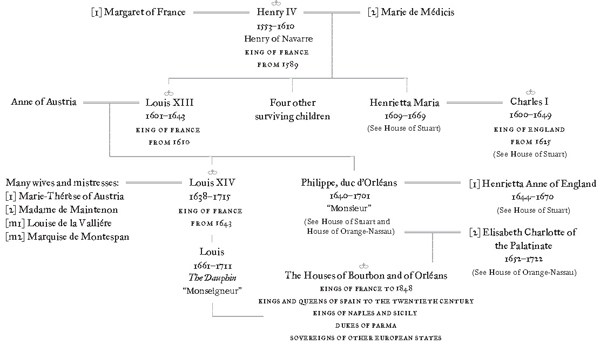

House of Bourbon

The Bourbon-Orléans family tree is infinitely larger, more ramified, and more intertangled than can possibly be shown here, largely owing to the longevity, fertility, and polygamy of Louis XIV. One of the mistresses of Louis XIV produced six children who were made legitimate by fiat, and another produced two.

“Er…stupid me…I’ve lost you…we’re speaking now of Oldenburg?”

“I intended no change in subject—we’re still on Treaties.”

The coach stopped. Pepys climbed out of it. Daniel listened to the whack, whack, whack of his slap-soled boots receding across cobblestones. Wilkins was staring at nothing, trying to decrypt whatever Pepys had said.

Riding in a carriage through London was only a little better than being systematically beaten by men with cudgels—Daniel felt the need for a stretch, and so he climbed out, too, turned round—and found himself looking straight down a lane toward the front of St. James’s Palace, a few hundred yards distant. Spinning round a hundred and eighty degrees, he discovered Comstock House, a stupefying Gothick pile heaving itself up out of some gardens and pavements. Pepys’s carriage had turned in off of Piccadilly and stopped in the great house’s forecourt. Daniel admired its situation: John Comstock could, if he so chose, plant himself in the center of his front doorway and fire a musket across his garden, out his front gate, across Piccadilly, straight down the center of a tree-lined faux-country lane, across Pall Mall, and straight into the grand entrance of St. James’s, where it would be likely to kill someone very well-dressed. Stone walls, hedges, and wrought-iron fences had been cunningly arranged so as to crop away the view of Piccadilly and neighboring houses, and enhance the impression that Comstock House and St. James’s Palace were all part of the same family compound.

Daniel edged out through Comstock’s front gates and stood at the margin of Piccadilly, facing south towards St. James’s. He could see a gentleman with a bag entering the Palace—probably a doctor coming to bleed a few pints from Anne Hyde’s jugular. Off to his left, in the general direction of the river, was an open space—a vast construction site, now—about a quarter of a mile on a side, with Charing Cross on the opposite corner. Since it was night, and no workers were around, it seemed as if stone foundations and walls were growing up out of the ground through some process of spontaneous generation, like toadstools bursting from soil in the middle of the night.

From here, it was possible to see Comstock House in perspective: it was really just one of several noble houses lined up along Piccadilly, facing towards St. James’s Palace, like soldiers drawn up for review. Berkeley House, Burlington House, and Gunfleet House were some of the others. But only Comstock House had that direct Palace view down the lane.

He felt a giant door grinding open, and heard dignified mur-murings, and saw that John Comstock had emerged from his house, arm in arm with Pepys. He was sixty-three years old, and Daniel thought that he was leaning on Pepys, just a bit, for support. But he had been wounded in battles more than once, so it didn’t necessarily mean he was getting feeble. Daniel sprang to the carriage and got Isaac’s telescope out of there and had the driver stow it securely on the roof. Then he joined the other three inside, and the carriage wheeled round and clattered out across Piccadilly and down the lane toward St. James’s.

John Comstock, Earl of Epsom, President of the Royal Society, and advisor to the King on all matters Natural-Philosophic, was dressed in a Persian vest—a heavy coatlike garment that, along with the Cravate, was the very latest at Court. Pepys was attired the same way, Wilkins was in completely outmoded clothing, Daniel as usual was dressed as a penniless itinerant Puritan from twenty years ago. Not that anyone was looking at him.

“Working late hours?” Comstock asked Pepys, apparently reading some clue in his attire.

“The Pay Office has been extraordinarily busy,” Pepys said.

“The King has been preoccupied with concerns of money—until recently,” Comstock said. “Now he is eager to turn his attentions back to his first love—natural philosophy.”

“Then we have something that will delight him—a new Telescope,” Wilkins began.

But telescopes were not on Comstock’s agenda, and so he ignored the digression, and continued: “His Majesty has asked me to arrange a convocation at Whitehall Palace tomorrow evening. The Duke of Gunfleet, the Bishop of Chester, Sir Winston Churchill, you, Mr. Pepys, and I are invited to join the King for a demonstration at Whitehall: Enoch the Red will show us Phosphorus.”

Just short of St. James’s Palace, the carriage turned left onto Pall Mall, and began to move up in the direction of Charing Cross.

“Light-bearer? What’s that?” Pepys asked.

“A new elemental substance,” Wilkins said. “All the alchemists on the Continent are abuzz over it.”

“What’s it made of?”

“It’s not made of anything—that’s what is meant by elemental!”

“What planet is it of? I thought all the planets were spoken for,” Pepys protested.

“Enoch will explain it.”

“Has there been any movement on the Royal Society’s other concern?”

“Yes!” Comstock said. He was looking into Wilkins’s eyes, but he made a tiny glance toward Daniel. Wilkins replied with an equally tiny nod.

“Mr. Waterhouse, I am pleased to present you with this order,” Comstock said, “from my Lord Penistone,”* producing a terrifying document with a fat wax seal dangling from the bottom margin. “Show it to the guards at the Tower tomorrow evening—and, even as we are at one end of London, viewing the Phosphorus Demo’, you and Mr. Oldenburg will be convened at the other so that you can see to his needs. I know that he wants new strings for his theorbo—quills—ink—certain books—and of course there’s an enormous amount of unread mail.”

“Unread by GRUBENDOL, that is,” Pepys jested.

Comstock turned and gave him a look that must’ve made Pepys feel as if he were staring directly into the barrel of a loaded cannon.

Daniel Waterhouse exchanged a little glance with the Bishop of Chester. Now they knew who’d been reading Oldenburg’s foreign letters: Comstock.

Comstock turned and smiled politely—but not pleasantly—at Daniel. “You’re staying at your elder half-brother’s house?”

“Just so, sir.”

“I’ll have the goods sent round tomorrow morning.”

The coach swung round the southern boundary of Charing Cross and pulled up before a fine new town-house. Daniel, having evidently out-stayed his relevance, was invited in the most polite and genteel way imaginable to exit the coach, and take a seat on top of it. He did so and realized, without really being surprised, that they had stopped in front of the apothecary shop of Monsieur LeFebure, King’s Chymist—the very same place where Isaac Newton had spent most of the morning, and had had an orchestrated chance encounter with the Earl of Upnor.

The front door opened and a man in a long cloak stepped out, silhouetted by lamplight from within, and approached the coach. As he got clear of the light shining out of the house, and moved across the darkness, it became possible to see that the hem of his cloak, and the tips of his fingers, shone with a strange green light.

“Well met, Daniel Waterhouse,” he said, and before Daniel could answer, Enoch the Red had climbed into the open door of the coach and closed it behind him.

The coach simply rounded the corner out of Charing Cross, which put them at one end of the long paved plaza before Whitehall. They drove directly towards the Holbein Gate, which was a four-turreted Gothic castle, taller than it was wide, that dominated the far end of the space. A huddle of indifferent gables and chimneys hid the big spaces off to their left: first Scotland Yard, which was an irregular mosaic of Wood Yards and Scalding Yards and Cider Houses, cluttered with coal-heaps and wood-piles, and after that, the Great Court of the Palace. On the right—where, during Daniel’s boyhood, there’d been nothing but park, and a view towards St. James’s Palace—there now loomed a long stone wall, twice as high as a man, and blank except for the gun-slits. Because Daniel was up on top of the carriage he could see a few tree-branches over its top, and the rooves of the wooden buildings that Cromwell had thrown up within those walls to house his Horse Guards. The new King—perhaps remembering that this plaza had once been filled with a crowd of people come to watch his father’s head get chopped off—had decided to keep the wall, and the gun-slits, and the Horse Guards.

The Palace’s Great Gate went by on the left, opening a glimpse of the Great Court and one or two big halls and chapels at the far end of it, down towards the river. More or less well-dressed pedestrians were going in and out of that gate, in twos and threes, availing themselves of a public right-of-way that led across the Great Court (it was clearly visible, even at night, as a rutted path over the ground) and that eventually snaked between, and through, various Palace Buildings and terminated at Whitehall Stairs, where water-men brought their little boats to pick up and discharge passengers.

The view through the Great Gate was then eclipsed by the corner of the Banqueting House, a giant white stone snuff-box of a building, which was kept dark on most nights so that torch-and candle-smoke would not blacken the buxom goddesses that Rubens had daubed on its ceiling. One or two torches were burning in there tonight, and Daniel was able to look up through a window and catch a glimpse of Minerva strangling Rebellion. But the carriage had nearly reached the end of the plaza now, and was slowing down, for this was an aesthetic cul-de-sac so miserable that it made even horses a bit woozy: the old quasi-Dutch gables of Lady Castlemaine’s apartments dead ahead; the Holbein Gate’s squat Gothic arch to the right and its medieval castle-towers looming far above their heads; the Italian Renaissance Banqueting House still on their left; and, across from it, that blank, slitted stone wall, which was as close as Puritans had ever come to having their own style of architecture.

The Holbein Gate would lead to King Street, which would take them to a sort of pied-à-terre that Pepys had in that quarter. But instead the driver chivvied his team around a difficult left turn and into a dark downhill passage, barely wider than the coach itself, that cut behind the Banqueting House and drained toward the river.

Now, any Englishman in decent clothing could walk almost anywhere in Whitehall Palace, even passing through the King’s antechamber—a practice that European nobility considered to be far beyond vulgar, deep into the realm of the bizarre. Even so, Daniel had never been down this defile, which had always seemed Not a Good Place for a Young Puritan to Go—he wasn’t even sure if it had an outlet, and always imagined that people like the Earl of Upnor would go there to molest serving-wenches or prosecute sword-duels.

The Privy Gallery ran along the right side of it. Now technically a gallery was just a hallway—in this case, one that led directly to those parts of Whitehall where the King himself dwelt, and toyed with his mistresses, and met with his counselors. But just as London Bridge had, over time, become covered over with houses and shops of haberdashers and glovers and drapers and publicans, so the Privy Gallery, tho’ still an empty tube of air, had become surrounded by a jumbled encrustation of old buildings—mostly apartments that the King awarded to whichever courtiers and mistresses were currently in his favor. These coalesced into a bulwark of shadow off to Daniel’s right, and seemed much bigger than they really were because of being numerous and confusing—as the corpse of a frog, which can fit into a pocket, seems to be a mile wide to the young Natural Philosopher who attempts to dissect it, and inventory its several parts.

Daniel was ambushed, several times, by explosions of laughter from candle-lit windows above: it sounded like sophisticated and cruel laughter. The passage finally bent round to the point where he could see its end. Apparently it debouched into a small pebbled court that he knew by reputation: the King, in theory, listened to sermons from the windows of various chambers and drawing-rooms that fronted on it. But before they reached that holy place the driver reined in his team and the carriage stopped. Daniel looked about, wondering why, and saw nothing except for a stone stairway that descended into a vault or tunnel beneath the Privy Gallery.

Pepys, Comstock, the Bishop of Chester, and Enoch the Red climbed out. Down in the tunnel, lights were now being lit. Consequently, through an open window, Daniel could see a banquet laid: a leg of mutton, a wheel of Cheshire, a dish of larks, ale, China oranges. But this room was not a dining-hall. In its corners he could see the gleam of retorts and quicksilver-flasks and fine balances, the glow of furnaces. He had heard rumors that the King had caused an alchemical laboratory to be built in the bowels of Whitehall, but until now, they had only been rumors.

“My coachman will take you back to Mr. Raleigh Waterhouse’s residence,” Pepys told him, pausing at the lip of the stairway. “Please make yourself comfortable below.”

“You are very kind, sir, but I’m not far from Raleigh’s, and I could benefit from the walk.”

“As you wish. Please give my compliments to Mr. Oldenburg when you see him.”

“I shall be honored to do so,” Daniel answered, and just restrained himself from saying, Please give mine to the King!

Daniel now worked up his courage and walked down into the Sermon Court and gazed up into the windows of the King’s chambers, though not for long—he was trying to look as if he came here all the time. A little side passage, under the end of the Privy Gallery, got him into the corner of the Privy Garden, which was a vast space. Another gallery ran along its edge, parallel to the river, and by going down it he could have got all the way to the royal bowling green and thence down into Westminster. But he’d had enough excitement for just now—instead he cut back across the great Garden, heading towards the Holbein Gate. Courtiers strolled and gossiped all round. Every so often he turned around and gazed back towards the river to admire the lodgings of the King and the Queen and their household rising up above the garden with the golden light of many beeswax candles shining out of them.

If Daniel had truly been the man about town that, for a few minutes, he was pretending to be, he’d have had eyes only for the people in the windows and on the garden paths. He’d have strained to glimpse something—a new trend in the cut of Persian vests, or two important Someones exchanging whispers in a shadowed corner. But as it was, there was one spectacle, and one only, that drew his gaze, like Polaris sucking on a lodestone. He turned his back on the King’s dwellings and looked south across the garden and the bowling green towards Westminster.

There, mounted up high on a weatherbeaten stick, was a sort of irregular knot of stuff, barely visible as a gray speck in the moonlight: the head of Oliver Cromwell. When the King had come back, ten years ago, he’d ordered the corpse to be dug up from where Drake and the others had buried it, and the head cut off and mounted on a pike and never taken down. Ever since then Cromwell had been looking down helplessly upon a scene of unbridled lewdness that was Whitehall Palace. And now Cromwell, who had once dandled Drake’s youngest son on his knee, was looking down upon him.

Daniel tilted his head back and looked up at the stars and supposed that seen from Drake’s perspective up in Heaven it must all look like Hell—and Daniel right in the middle of it.

BEING LOCKED UP in the Tower of London had changed Henry Oldenburg’s priorities all around. Daniel had expected that the Secretary of the Royal Society would jump headfirst into the great sack of foreign mail that Daniel had brought him, but all he cared about was the new lute-strings. He’d grown too fat to move around very effectively and so Daniel fetched necessaries from various parts of the half-moon-shaped room: Oldenburg’s lute, extra candles, a tuning-fork, some sheet-music, more wood on the fire. Oldenburg turned the lute over across his knees like a naughty boy for spanking, and tied a piece of gut or two around the instrument’s neck to serve as frets (the old ones being worn through), then replaced a couple of broken strings. Half an hour of tuning ensued (the new strings kept stretching) and then, finally, Oldenburg got what he really ached for: he and Daniel, sitting face to face in the middle of the room, sang a two-part song, the parts cleverly written so that their voices occasionally joined in chords that resonated sweetly: the curving wall of the cell acting like the mirror of Newton’s telescope to reflect the sound back to them. After a few verses, Daniel had his part memorized, and so when he sang the chorus he sat up straight and raised his chin and sang loudly at those walls, and read the graffiti cut into the stone by prisoners of centuries past. Not your vulgar Newgate Prison graffiti—most of it was in Latin, big and solemn as gravestones, and there were astrological diagrams and runic incantations graven by imprisoned sorcerers.

Then some ale to cool the wind-pipes, and a venison pie and a keg of oysters and some oranges contributed by the R.S., and Oldenburg did a quick sort of the mail—one pile containing the latest doings of the Hotel Montmor salon in Paris, a couple of letters from Huygens, a short manuscript from Spinoza, a large pile of ravings sent in by miscellaneous cranks, and a Leibniz-mound. “This damned German will never shut up!” Oldenburg grunted—which, since Oldenburg was himself a notoriously prolix German, was actually a jest at his own expense. “Let me see…Leibniz proposes to found a Societas Eruditorum that will gather in young Vagabonds and raise them up to be an army of Natural Philosophers to overawe the Jesuits…here are his thoughts on free will versus predestination…it would be great sport to get him in an argument with Spinoza…he asks me here whether I’m aware Comenius has died…says he’s ready to pick up the faltering torch of Pan-sophism*…here’s a light, easy-to-read analysis of how the bad Latin used by Continental scholars leads to faulty thinking, and in turn to religious schism, war, bad philosophy…”

“Sounds like Wilkins.”

“Wilkins! Yes! I’ve considered decorating these walls with some graffiti of my own, and writing it in the Universal Character…but it’s too depressing. ‘Look, we have invented a new Philosophickal Language so that when we are imprisoned by Kings we can scratch a higher form of graffiti on our cell walls.’ ”

“Perhaps it’ll lead us to a world where Kings can’t, or won’t, imprison us at all—”

“Now you sound like Leibniz. Ah, here are some new mathematical proofs…nothing that hasn’t been proved already, by Englishmen…but Leibniz’s proofs are more elegant…here’s something he has modestly entitled Hypothesis Physica Nova. Good thing I’m in the Tower, or I’d never have time to read all this.”

Daniel made coffee over the fire—they drank it and smoked Virginia tobacco in clay-pipes. Then it was time for Oldenburg’s evening constitutional. He preceded Daniel down a stack of stone pie-wedges that formed a spiral stair. “I’d hold the door and say ‘after you,’ but suppose I fell—you’d end up in the basement of Broad Arrow Tower crushed beneath me—and I’d be in the pink.”

“Anything for the Royal Society,” Daniel jested, marveling at how Oldenburg’s bulk filled the helical tube of still air.

“Oh, you’re more valuable to them than I am,” Oldenburg said.

“Poh!”

“I am near the end of my usefulness. You are just beginning. They have great plans for you—”

“Until yesterday I wouldn’t’ve believed you—then I was allowed to hear a conversation—perfectly incomprehensible to me—but it sounded frightfully important.”

“Tell me about this conversation.”

They came out onto the top of the old stone curtain-wall that joined Broad Arrow Tower to Salt Tower on the south. Arm in arm, they strolled along the battlements. To the left they could look across the moat—an artificial oxbow-lake that communicated with the Thames—and a defensive glacis beyond that, then a few barracks and warehouses having to do with the Navy, and then the pasture-grounds of Wapping crooked in an elbow of the Thames, dim lights out at Ratcliff and Limehouse—then a blackness containing, among other things, Europe.

“The Dramatis Personae: John Wilkins, Lord Bishop of Chester, and Mr. Samuel Pepys Esquire, Admiral’s Secretary, Treasurer of the Fleet, Clerk of Acts of the Navy Board, deputy Clerk of the Privy Seal, Member of the Fishery Corporation, Treasurer of the Tangier Committee, right-hand-man of the Earl of Sandwich, courtier…am I leaving anything out?”

“Fellow of the Royal Society.”

“Oh, yes…thank you.”

“What said they?”

“First a brief speculation about who was reading your mail…”

“I assume it’s John Comstock. He spied for the King during the Interregnum, why can’t he spy for the King now?”

“Rings true…this led to some double entendres about tender negotiations. Mr. Pepys volunteered—speaking of the King of England, here—‘his feelings for sa soeur are most affectionate, he’s writing many letters to her.’ ”

“Well, you know that Minette is in France—”

“Minette?”

“That is what King Charles calls Henrietta Anne, his sister,” Oldenburg explained. “I don’t recommend using that name in polite society—unless you want to move in with me.”

“She’s the one who’s married to the Duc d’Orléans*—?”

“Yes, and Mr. Pepys’s lapsing into French was of course a way of emphasizing this. Pray continue.”

“My Lord Wilkins wondered whether she wrote back, and Pepys said Minette was spewing out letters like a diplomat.”

Oldenburg cringed, and shook his head in dismay. “Very crude work on Mr. Pepys’s part. He was letting it be known that this exchange of letters was some sort of diplomatic negotiation. But he did not need to be so coarse with Wilkins…he must have been tired, distracted…”

“He’d been working late—lots of gold going into the Navy Treasury under cover of darkness.”

“I know it—behold!” Oldenburg said, and, tightening his arm, swung Daniel round so that both of them were looking west, across the Inmost Ward. They were near Salt Tower, which was the southeastern corner of the squarish Tower complex. The southern wall, therefore, stretched away from them, paralleling the river, connecting a row of squat round towers. Off to their right, planted in the center of the ward, was the ancient donjon: a freestanding building called the White Tower. A few low walls partitioned the ward into smaller quadrangles, but from this viewpoint the most conspicuous structure was the great western wall, built strong to resist attack from the always difficult City of London. On the far side of that wall, hidden from their view, a street ran up a narrow defile between it and a somewhat lower outer wall. Stout piles of smoke and steam were building from that street—which was lined with works for melting and working precious metals. It was called Mint Street. “Their infernal hammers keep me awake—the smoke of their furnaces comes in through the embrasures.” Walls hereabouts tended to have narrow cross-shaped arrow-slits called embrasures, which was one of the reasons the Tower made a good prison, especially for fat men.

“So that’s why kings live at Whitehall nowadays—to be upwind of the Mint?” Daniel said jestingly.

On Oldenburg’s face, perfunctory amusement stamped out by pedantic annoyance. “You don’t understand. The Mint’s operations are extremely sporadic—it has been cold and silent for months—the workers idle and drunk.”

“And now?”

“Now they are busy and drunk. A few days ago, as I stood in this very place, I saw a three-master, a man of war, heavily laden, drop anchor just around the river-bend, there. Small boats carrying heavy loads began to put in at the water-gate just there, in the middle of the south wall. On the same night, the Mint came suddenly to life, and has not slept since.”

“And gold began to arrive at the Navy Treasury,” Daniel said, “making much work for Mr. Pepys.”

“Now, let us get back to this conversation you were allowed to hear. How did the Bishop of Chester respond to Mr. Pepys’s rather ham-handed revelations?”

“He said something like, ‘So Minette keeps his Majesty well acquainted with the doings of her beau?’”

“Now whom do you suppose he meant by that?”

“Her husband—? I know, I know—my naïveté is pathetic.”

“Philippe, duc d’Orleans, owns the largest and finest collection of women’s underwear in France—his sexual adventures are strictly limited to being fucked up the ass by strapping officers.”

“Poor Minette!”

“She knew perfectly well when she married him,” Oldenburg said, rolling his eyes. “She spent her honeymoon in bed with her new husband’s elder brother: King Louis XIV. That is what Bishop Wilkins meant when he referred to Minette’s beau.”

“I stand corrected.”

“Pray go on.”

“Pepys assured Wilkins that, considering the volume of correspondence, King Charles couldn’t help but be very close to the man in question—an analogy was made to hoops of gold…”

“Which you took to mean, matrimonial bliss?”

“Even I knew what Pepys meant by that,” Daniel said hotly.

“So did Wilkins, I’m sure—how did he seem, then?”

“Ill at ease—he wanted reassurance that ‘the two arch-Dissenters’ were handling formal contacts.”

“It is a secret—but generally known among the sort who rattle around London in private coaches in the night-time—that a treaty with France is being negotiated by the Earl of Shaftesbury, and His Majesty’s old drinking and whoring comrade, the Duke of Buckingham. Chosen for the job not because they are skilled diplomats but because not even your late father would ever accuse them of Popish sympathies.”

A Yeoman Warder was approaching, making his rounds. “Good evening, Mr. Oldenburg. Mr. Waterhouse.”

“Evening, George. How’s the gout?”

“Better today, thank you, sir—the cataplasm seemed to work—where did you get the receipt from?” George then went into a rote exchange of code-words with another Beefeater on the roof of Salt Tower, then reversed direction, bade them good evening, and strolled away.

Daniel enjoyed the view until he was certain that the only creature that could overhear them was a spaniel-sized raven perched on a nearby battlement.

Half a mile upstream, the river was combed, and nearly dammed up, by a line of sloppy, boat-shaped, man-made islands, supporting a series of short and none too ambitious stone arches. The arches were joined, one to the next, by a roadway, made of wood in some places and of stone in others, and the roadway was mostly covered with buildings that sprayed in every direction, cantilevered far out over the water and kept from falling into it by makeshift diagonal braces. Far upstream, and far downstream, the river was placid and sluggish, but where it was forced between those starlings (as the man-made islands were called), it was all furious. The starlings themselves, and the banks of the Thames for miles downstream, were littered with wreckage of light boats that had failed in the attempt to shoot the rapids beneath London Bridge, and (once a week or so) with the corpses and personal effects of their passengers.

A few parts of the bridge had been kept free of buildings so that fires could not jump the river. In one of those gaps a burly woman stopped to fling a jar into the angry water below. Daniel could not see it from here, but he knew it would be painted with a childish rendering of a face: this a charm to ward off witch-spells. The water-wheels constructed in some of those arch-ways made gnashing and clanking noises that forced Waterhouse and Oldenburg, half a mile away, to raise their voices slightly, and put their heads closer together. Daniel supposed this was no accident—he suspected they were coming to a part of the conversation that Oldenburg would rather keep private from those sharp-eared Beefeaters.

Directly behind London Bridge, but much farther away round the river-bend, were the lights of Whitehall Palace, and Daniel almost convinced himself that there was a greenish glow about the place tonight, as Enoch the Red schooled the King, and his court, and the most senior Fellows of the Royal Society, in the new Element called Phosphorus.

“Then Pepys got too enigmatic even for Wilkins,” Daniel said. “He said, ‘I refer you to Chapter Ten of your 1641 work.’”

“The Cryptonomicon ?”

“So I assume. Chapter Ten is where Wilkins explains steganog-raphy, or how to embed a subliminal message in an innocuous-seeming letter—” but here Daniel stopped because Oldenburg had adopted a patently fake look of innocent curiosity. “I think you know this well enough. Now, Wilkins apologized for being thickheaded and asked whether Pepys was speaking, now, of you.”

“Ho, ho, ho!” Oldenburg bellowed, the laughter bouncing like cannon-fire off the hard walls of the Inmost Ward. The raven hopped closer to them and screeched, “Caa, caa, caa!” Both humans laughed, and Oldenburg fetched a bit of bread from his pocket and held it out to the bird. It hopped closer and reared back to peck it out of the fat pale hand—but Oldenburg snatched it back and said very distinctly, “Cryptonomicon.”

The raven cocked its head, opened its beak, and made a long gagging noise. Oldenburg sighed and opened his hand. “I have been trying to teach him words,” he explained, “but that one is too much of a mouthful, for a raven.” The bird’s beak struck the bread out of Oldenburg’s hand, and it hopped back out of reach, in case Oldenburg should change his mind.

“Wilkins’s confusion is understandable—but Pepys’s meaning is clear. There are some suspicious-minded persons upriver” (waving in the general direction of Whitehall) “who think I’m a spy, communicating with Continental powers by means of subliminal messages embedded in what purport to be philosophickal discourses—it being beyond their comprehension that anyone would care as much as I seem to about new species of eels, methods for squaring hyperbolae, et cetera. But Pepys was not referring to that—he was being ever so much more clever. He was telling Wilkins that the not-very-secret negotiations being carried on by Buckingham and Shaftesbury are like the innocuous-seeming message, being used to conceal the truly secret agreement that the two Kings are drawing up, using Minette as the conduit.”

“God in Heaven,” Daniel said, and felt obliged to lean back against a battlement so that his spinning head wouldn’t whirl him off into the moat.

“An agreement whose details we can only guess at—except for this: it causes gold to appear there in the middle of the night.” Oldenburg pointed to the Tower’s water-gate along the Thames. Discretion kept him from speaking its ancient name: Traitor’s Gate.

“Pepys mentioned in passing that Thomas More Anglesey was responsible for filling the Navy’s coffers…I didn’t understand what he meant.”

“Our Duke of Gunfleet has much warmer connections with France than anyone appreciates,” Oldenburg said—but then refused to say any more.

And because silver and gold have their value from the matter itself; they have first this privilege, that the value of them cannot be altered by the power of one, nor of a few commonwealths; as being a common measure of the commodities of all places. But base money, may easily be enhanced, or abased.

—HOBBES, Leviathan

OLDENBURG GENTEELLY KICKED him out not much later, eager to get into that pile of mail. Under the politely curious gaze of the Beefeaters and their semi-tame ravens, Daniel walked down Water Lane, on the southern verge of the Tower complex. He walked past a large rectangular tower planted in the outer wall, above the river, and realized too late that if he’d only turned his head and glanced to the left at that point, he could’ve looked through the giant arch of Traitor’s Gate and out across the river. Too late now—seemed a poor idea to go back. Probably just as well he hadn’t gawked—then whoever was watching him would suspect that Oldenburg had mentioned it.

Was he thinking like a courtier now?

The massive octagonal pile of Bell Tower was on his right. As he got past it he dared to look up a narrow buffer between two layers of curtain-walls no more than fifty feet apart. Half of that width was filled up by the Mint’s indifferent low houses and workshops. Daniel glimpsed furnace-light radiating from windows, warming high stone walls, making silhouettes of a congestion of carts bringing coal to burn. Men with muskets gazed coolly back at him. Mint workers crossed from building to building in the shambling gait of the exhausted.

Then he was underneath the great arch of the Byward Tower, an elevated building thrown over Water Lane to control the Tower’s land approach. A raven perched on a gargoyle and screeched “Cromwell!” at him as he passed through onto the drawbridge that ran from Byward Tower out to Middle Tower, over the moat. Middle Tower gave way to Lion Tower—but the King’s menagerie were all asleep and he did not hear the lions roar. From there he crossed over a last little backwater of the moat, over another drawbridge, and came into a little walled-in yard called the Bulwark—finally, then, through one last gate and into the world, though he had a lonely stroll over an empty moonlit glacis, past a few scavenging rats and copulating dogs, before he was among buildings and people.

But then Daniel Waterhouse was right in the City of London—slightly confused, as some of the streets had been straightened and simplifed after the Fire. He pulled a fat gold egg from his pocket—one of Hooke’s experimental watches, a failed stab at the Longitude Problem, adequate only for landlubbers. It told him that the Phosphorus Demo’ was not quite finished at Whitehall, but that it was not too late to call on his in-laws. Daniel did not especially like to just call on people—seemed presumptuous to think they’d want to open the door and see him—but he knew that this was how men like Pepys got to become men like Pepys. So to the house of Ham.

Lights burned expensively, and a coach and pair dawdled out front. Daniel was startled to discover his own family coat of arms (a castle bestriding a river) painted on the door of this coach. The house was smoking like a heavy forge—it was equipped with oversized chimneys, projecting tubes of orange light into their own smoke. As Daniel ascended the front steps he heard singing, which faltered but did not stop when he knocked: a very current melody making fun of the Dutch for being so bright, hard-working, and successful. Viscount Walbrook’s* butler opened the door and recognized Daniel as a social caller—not, as sometimes happened, a nocturnal customer brandishing a goldsmith’s note.

Mayflower Ham, neé Waterhouse—tubby, fair, almost fifty, looking more like thirty—gave him a hug that pulled him up on tiptoe. Menopause had finally terminated her fantastically involved and complex relationship with her womb: a legendary saga of irregular bleeding, eleven-month pregnancies straight out of the Royal Society proceedings, terrifying primal omens, miscarriages, heartbreaking epochs of barrenness punctuated by phases of such explosive fertility that Uncle Thomas had been afraid to come near her—disturbing asymmetries, prolapses, relapses, and just plain lapses, hellish cramping fits, mysterious interactions with the Moon and other cœlestial phenomena, shocking imbalances of all four of the humours known to Medicine plus a few known only to Mayflower, seismic rumblings audible from adjoining rooms—cancers reabsorbed—(incredibly) three successful pregnancies culminating in four-day labors that snapped stout bedframes like kindling, vibrated pictures off walls, and sent queues of vicars, mid-wives, physicians, and family members down into their own beds, ruined with exhaustion. Mayflower had (fortunately for her!) been born with that ability, peculiar to certain women, of being able to talk about her womb in any company without it seeming inappropriate, and not only that but you never knew where in a conversation, or a letter, she would launch into it, plunging everyone into a clammy sweat as her descriptions and revelations forced them to consider topics so primal that they were beyond eschatology—even Drake had had to shut up about the Apocalypse when Mayflower had gotten rolling. Butlers fled and serving-maids fainted. The condition of Mayflower’s womb affected the moods of England as the Moon ruled the tides.

“How, er…are you?” Daniel inquired, bracing himself, but she just smiled sweetly, made rote apologies about the house not being finished (but no fashionable house ever was finished), and led him to the Dining-Room, where Uncle Thomas was entertaining Sterling and Beatrice Waterhouse, and Sir Richard Apthorp and his wife. The Apthorps had a goldsmith’s shop of their own, and lived a few doors up Threadneedle. The attire was not so aggressively fine, Daniel not so monstrously out of place, as at the coffee-house. Sterling greeted him warmly, as if saying, Sorry old chap but the other day was business.

They appeared to be celebrating something. Reference was made to all the work that lay ahead, so Daniel assumed it was some milestone in their grand shop-house-project. He wanted someone to ask him where he’d been, so that he could offhandedly let them know he’d been to the Tower waving around a warrant from the Secretary of State. But no one asked. After a while he realized that they probably would not care if they did know. The back door, fronting on Cornhill, kept creaking open, then booming shut. Finally, Daniel caught Uncle Thomas’s eye, and, with a look, inquired what on earth was happening back there. A few minutes later, Viscount Walbrook got up, as if to use the House of Office, but tapped Daniel on the shoulder on his way out of the room.

Daniel rose and followed him down a hall—dark except for a convenient red glow at the far end. Daniel couldn’t see around the tottering Punchinello silhouette of his host, but he could hear shovels crunching into piles of something, ringing as they flung their loads—obviously coal being fed to a furnace. But sometimes there was the icy trill of a coin falling and spinning on a hard floor.

The hall became sooty and extremely warm, and gave way to a brick-lined room where a laborer, stripped to a pair of drawers, was heaving coal into the open door of the House of Ham’s forge—which had been hugely expanded when the house was reconstructed after the Fire. Another laborer was pumping bellows with his feet, climbing an endless ladder. In the old days, this forge had been a good size for baking tarts, which made sense for the sort of goldsmith who made earrings and teaspoons. Now it looked like something that could be used to cast cannon-barrels, and half the weight of the building was concentrated in the chimney.

Several black iron lock-boxes were open on the floor—some full of silver coins and others empty. One of the Hams’ senior clerks sat on the floor by one of these in a pond of his own sweat, counting coins into a dish out loud: “Ninety-eight…ninety-nine…hundred!” whereupon he handed the dish up to Charles Ham (the youngest Ham brother—Thomas being the eldest), who emptied it onto the pan of a scale and weighed the coins against a brass cylinder—then raked them off into a bucket-sized crucible. This was repeated until the crucible was nearly full. Then a glowing door was opened—knives of blue flame probed out into the dark room—Charles Ham donned black gauntlets, heaved a gigantic pair of iron tongs off the floor, thrust them in, hugged, and backed away, drawing out another crucible: a cup shining daffodil-colored light. Turning around very carefully, he positioned the crucible (Daniel could’ve tracked it with his eyes closed, by feeling its warmth shine on his face) and tipped it. A stream of radiant liquid formed in its lip and arced down into a mold of clay. Other molds were scattered about the floor, wherever there was room, cooling down through shades of yellow, orange, red, and sullen brown, to black; but wherever light glanced off of them, it gleamed silver.

When the crucible was empty, Charles Ham set it down by the scales, then picked up the crucible that was full of silver coins and put it into the fire. Through all of this, the man on the floor never paused counting coins out of the lock-box, his reedy voice making a steady incantation out of the numbers, the coins going chink, chink, chink.

Daniel stepped forward, bent down, took a coin out of the lockbox, and angled it to shine fire-light into his eyes, like the little mirror in the center of Isaac’s telescope. He was expecting to see a worn-out shilling with a blurred portrait of Queen Elizabeth on it, or an old piece of eight or thaler that the Hams had somehow picked up in a money-changing transaction. What he saw was in fact the profile of King Charles II, very new and crisp, stamped on a limpid pool of brilliant silver—perfect. Shining that way in firelight, it brought back memories of a night in 1666. Daniel flung it back into the lock-box. Then, not believing his eyes, he thrust his hand in and pulled out a fistful. They were all the same. Their edges, fresh from Monsieur Blondeau’s ingenious machine, were so sharp they almost cut his flesh, their mass blood-warm…

The heat was too much. He was out in the street with Uncle Thomas, bathing in cool air.

“They are still warm!” he exclaimed.

Uncle Thomas nodded.

“From the Mint?”

“Yes.”

“You mean to tell me that the coins being stamped out at the Mint are, the very same night, melted down into bullion on Thread-needle Street?”

Daniel was noticing, now, that the chimney of Apthorp’s shop, two doors up the street, was also smoking, and the same was true of diverse other goldsmiths up and down the length of Threadneedle.

Uncle Thomas raised his eyebrows piously.

“Where does it go then?” Daniel demanded.

“Only a Royal Society man would ask,” said Sterling Waterhouse, who had slipped out to join them.

“What do you mean by that, brother?” Daniel asked.

Sterling was walking slowly towards him. Instead of stopping, he flung his arms out wide and collided with Daniel, embraced him and kissed him on the cheek. Not a trace of liquor on his breath. “No one knows where it goes—that is not the point. The point is that it goes—it moves—the movement ne’er stops—it is the blood in the veins of Commerce.”

“But you must do something with the bullion—”

“We tender it to gentlemen who give us something in return” said Uncle Thomas. “It’s like selling fish at Billingsgate—do the fishwives ask where the fish go?”

“It’s generally known that silver percolates slowly eastwards, and stops in the Orient, in the vaults of the Great Mogul and the Emperor of China,” Sterling said. “Along the way it might change hands hundreds of times. Does that answer your question?”

“I’ve already stopped believing I saw it,” Daniel said, and went back into the house, his thin shoe-leather bending over irregular paving-stones, his dull dark clothing hanging about him coarsely, the iron banister cold under his hand—he was a mote bobbing in a mud-puddle and only wanted to be back in the midst of fire and heat and colored radiance.

He stood in the forge-room and watched the melting for a while. His favorite part was the sight of the liquid metal building behind the lip of the canted crucible, then breaking out and tracing an arc of light down through the darkness.

“Quicksilver is the elementary form of all things fusible; for all things fusible, when melted, are changed into it, and it mingles with them because it is of the same substance with them…”

“Who said that?” Sterling asked—keeping an eye on his little brother, who was showing signs of instability.

“Some damned Alchemist,” Daniel answered. “I have given up hope, tonight, of ever understanding money.”

“It’s simple, really…”

“And yet it’s not simple at all,” Daniel said. “It follows simple rules—it obeys logic—and so Natural Philosophy should understand it, encompass it—and I, who know and understand more than almost anyone in the Royal Society, should comprehend it. But I don’t. I never will…if money is a science, then it is a dark science, darker than Alchemy. It split away from Natural Philosophy millennia ago, and has gone on developing ever since, by its own rules…”

“Alchemists say that veins of minerals in the earth are twigs and offshoots of an immense Tree whose trunk is the center of the earth, and that metals rise like sap—” Sterling said, the firelight on his bemused face. Daniel was too tired at first to take the analogy—or perhaps he was underestimating Sterling. He assumed Sterling was prying for suggestions on where to look for gold mines. But later, as Sterling’s coach was taking him off towards Charing Cross, he understood that Sterling had been telling him that the growth of money and commerce was—as far as Natural Philosophers were concerned—like the development of that mysterious subterranean Tree: suspected, sensed, sometimes exploited for profit, but, in the end, unknowable.

THE KING’S HEAD TAVERN was dark, but it was not closed. When Daniel entered he saw patches of glowing green light here and there—pooled on tabletops and smeared on walls—and heard Persons of Quality speaking in hushed voices punctuated by outbreaks of riotous giggling. But the glow faded, and then serving-wenches scurried out with rush-lights and re-lit all of the lamps, and finally Daniel could see Pepys and Wilkins and Comstock, and the Duke of Gunfleet, and Sir Christopher Wren, and Sir Winston Churchill, and—at the best table—the Earl of Upnor, dressed in what amounted to a three-dimensional Persian carpet, trimmed with fur and studded with globs of colored glass, or perhaps they were precious gems.

Upnor was explaining phosphorus to three gaunt women with black patches glued all over their faces and necks: “It is known, to students of the Art, that each metal is created when rays from a particular planet strike and penetrate the Earth, videlicet, the Sun’s rays create gold; the Moon’s, silver; Mercury’s, quicksilver; Venus’s, copper; Mars’s, iron; Jupiter’s, tin; and Saturn’s lead. Mr. Root’s discovery of a new elemental substance suggests there may be another planet—presumably of a green color—beyond the orbit of Saturn.”

Daniel edged toward a table where Churchill and Wren were talking past each other, staring ever so thoughtfully at nothing: “It faces to the east, and it’s rather far north, isn’t it? Perhaps His Majesty should name it New Edinburgh…”

“That would only give the Presbyterians ideas!” Churchill scoffed.

“It’s not that far north,” Pepys put in from another table. “Boston is farther north by one and a half degrees of latitude.”

“We can’t go wrong suggesting that he name it after himself…”

“Charlestown? That name is already in use—Boston again.”

“His brother then? But Jamestown was used in Virginia.”

“What are you talking about?” Daniel inquired.

“New Amsterdam! His Majesty is acquiring it in exchange for Surinam,” Churchill said.

“Speak up, Sir Winston, there may be some Vagabonds out in Dorset who didn’t hear you!” Pepys roared.

“His Majesty has asked the Royal Society to suggest a new name for it,” Churchill added, sotto voce.

“Hmmm…his brother sort of conquered the place, didn’t he?” Daniel asked. He knew the answer, but couldn’t presume to lecture men such as these.

“Yes,” Pepys said learnedly, “ ‘twas all part of York’s Atlantic campaign—first he took several Guinea ports, rich in gold, and richer in slaves, from the Dutchmen, and then it was straight down the trade winds to his next prize—New Amsterdam.”

Daniel made a small bow toward Pepys, then continued: “If you can’t use his Christian name of James, perhaps you can use his title…after all, York is a city up to the north on our eastern coast—and yet not too far north…”

“We have already considered that,” Pepys said glumly. “There’s a Yorktown in Virginia.”

“What about ‘New York’?” Daniel asked.

“Clever…but too obviously derivative of ‘New Amsterdam,’” Churchill said.

“If we call it ‘New York,’ we’re naming it after the city of York…the point is to name it after the Duke of York,” Pepys scoffed.

Daniel said, “You are correct, of course—”

“Oh, come now!” Wilkins barked, slapping a table with the flat of his hand, splashing beer and phosphorus all directions. “Don’t be pedantic, Mr. Pepys. Everyone will understand what it means.”

“Everyone who is clever enough to matter, anyway,” Wren put in.

“Err…I see, you are proposing a more subtile approach,” Sir Winston Churchill muttered.

“Let’s put it on the list!” Wilkins suggested. “It can’t hurt to include as many ‘York’ and ‘James’ names as we can possibly think up.”

“Hear, hear!” Churchill harrumphed—or possibly he was just clearing his throat—or summoning a barmaid.

“As you wish—never mind,” Daniel said. “I take it that Mr. Root’s Demonstration was well received—?”

For some reason this caused eyes to swivel, ever so briefly, toward the Earl of Upnor. “It went well,” Pepys said, drawing closer to Daniel, “until Mr. Root threatened to spank the Earl. Don’t look at him, don’t look at him,” Pepys continued levelly, taking Daniel’s arm and turning him away from the Earl. The timing was unfortunate, because Daniel was certain he had just overhead Upnor mentioning Isaac Newton by name, and wanted to eavesdrop.

Pepys led him past Wilkins, who was good-naturedly spanking a barmaid. The publican rang a bell and everyone blew out the lights—the tavern went dark except for the freshly invigorated phosphorus. Everyone said “Woo!” and Pepys wrangled Daniel out into the street. “You know that Mr. Root makes the stuff from urine?”

“So it is rumored,” Daniel said. “Mr. Newton knows more of the Art than I do—he has told me that Enoch the Red was following an ancient recipe to extract the Philosophic Mercury from urine, but happened upon phosphorus instead.”

“Yes, and he has an entire tale that he tells, of how he found the recipe in Babylonia.” Pepys rolled his eyes. “Enthralled the courtiers. Anyway—for this evening’s Demo’, he’d collected urine from a sewer that drains Whitehall, and boiled it—endlessly—on a barge in the Thames. I’ll spare you the rest of the details—suffice it to say that when it was finished, and they were done applauding, and all of the courtiers were groping for a way to liken the King’s splendor and radiance to that of Phosphorus—”

“Oh, yes, I suppose that would’ve been obligatory—?”

Wilkins banged out the tavern door, apparently just to watch the story being related to Daniel.

“The Earl of Upnor made some comment to the effect that some kingly essence—a royal humour—must suffuse the King’s body, and be excreted in his urine, to account for all of this. And when all of the other courtiers were finished agreeing, and marveling at the Earl’s philosophick acumen, Enoch the Red said, ‘In truth, most of this urine came from the Horse Guards—and their horses.’”

“Whereat, the Earl was on his feet! His hand reaching for his sword—to defend His Majesty’s honor, of course,” Wilkins said.

“What was His Majesty’s state of mind?” Daniel asked.

Wilkins made his hands into scale-pans and bobbled them up and down. “Then Mr. Pepys tipped the scales. He related an anecdote from the Restoration, in 1660, when he had been on the boat with the King, and certain members of his household—including the Earl of Upnor, then no more than twelve years old. Also aboard was the King’s favorite old dog. The dog shit in the boat. The young Earl kicked at the dog, and made to throw it overboard—but was stayed by the King, who laughed at it, and said, ‘You see, in some ways, at least, Kings are like other men!’”