SUMMER 1684

Trade, like Religion, is what every Body talks of, but few understand: The very Term is dubious, and in its ordinary Acceptation, not sufficiently explain’d.

—DANIEL DEFOE, A Plan of the English Commerce

“IF NOTHING HAPPENS IN AMSTERDAM, save that everything going into it, turns round and comes straight back out—”

“Then there must be nothing else there,” Eliza finished.

Neither one of them had ever been to Amsterdam—yet. But the amount of stuff moving toward that city, and away from it, on the roads and canals of the Netherlands, was so vast that it made Leipzig seem like a smattering of poor actors in the background of a play, moving back and forth with a few paltry bundles to create the impression of commerce. Jack had not seen such bunching-together of people and goods since the onslaught on Vienna. But that had only happened once, and this was continuous. And he knew by reputation that what came in and out of Amsterdam over land, compared to what was carried on ships, was a runny nose compared to a river.

Eliza was dressed in a severe black ensemble with a high stiff white collar: a prosperous Dutch farmer’s wife to all appearances, except that she spoke no Dutch. During their weeks of almost mortally tedious westing across the Duchy of Braunschweig-Wolfenbüttel, the Duchy of Braunschweig-Lüneburg, the Bishopric of Hildesheim, Duchy of Kalenberg, Landgraviate of something-or-other, County of Lippe, County of Ravensburg, Bishopric of Osnabrück, County of Lingen, Bishopric of Münster, and County of Bentheim, she had mostly gone in man’s attire, booted, sworded, and spurred. Not that anyone really believed she was a man: she was pretending to be an Italian courtesan on her way to a tryst with a Genoese banker in Amsterdam. This made hardly any sense at all, but, as Jack had learned, border guards mostly just wanted something to relieve the tedium. It was easier to flaunt Eliza than to hide her. Trying to predict when they’d reach the next frontier, and whether the people on the far side of it would be Protestant or Catholic, and how serious about being Prot. or Cath. they’d be, was simply too difficult. Much simpler to be saucily irreligious everywhere and, if people got offended, run away. It worked most places. The locals had other concerns: if half the rumors were true, then King Looie—not satisfied with bombarding Genoa, laying siege to Luxembourg, challenging Pope Innocent XI to a staredown, expelling Jewry from Bordeaux, and massing his armies on the Spanish border—had just announced that he owned northwestern Germany. As they happened to be in northwestern Germany, this made matters tense, yet fluid, in a way that was not entirely bad for them.

Great herds of scrawny young cattle were being driven across the plain out of the East to be fattened in the manmade pastures of the Netherlands. Commingled with them were hordes of unemployed men going to look for work in Dutch cities—Holland-gänger, they were called. So the borders were easy, except along the frontier of the Dutch Republic, where all the lines of circumvallation ran across their path: not only the natural rivers but walls, ditches, ramparts, palisades, moats, and pickets: some new and crisp and populated by soldiers, others the abandoned soft-edged memories of battles that must have happened before Jack had been born. But after being chased off a time or two, in ways that would probably seem funny when remembered later, they penetrated into Gelderland: the eastern marches of that Republic. Jack had patiently inculcated Eliza in the science of examining the corpses, heads, and limbs of executed criminals that decorated all city gates and border-posts, as a way of guessing what sorts of behavior were most offensive to the locals. What it came down to, here, was that Eliza was in black and Jack was on his crutch, with no weapons, and as little flesh as possible, in sight.

There were tolls everywhere, but no center of power. The cattle-herds spread out away from the high road and into pastures flat as ponds, leaving them and the strewn parades of Hollandgänger to traipse along for a day or two, until they began joining up with other, much greater roads from the south and east: nearly unbroken queues of carts laden with goods, fighting upstream against as heavy traffic coming from the north. “Why not just stop and trade in the middle of the road?” Jack asked, partly because he knew it would provoke Eliza. But she wasn’t provoked at all—she seemed to think it was a good question, such as the philosophical Doctor might’ve asked. “Why indeed? There must be a reason. In commerce there is a reason for everything. That’s why I like it.”

The landscape was long skinny slabs of flat land divided one from the next by straight ditches full of standing water, and what happened on that land was always something queer: tulip-raising, for example. Individual vegetables being cultivated and raised by hand, like Christmas geese, and pigs and calves coddled like rich men’s children. Odd-looking fields growing flax, hemp, rape, hops, tobacco, woad, and madder. But queerest of all was that these ambitious farmers were doing things that had nothing to do with farming: in many places he saw women bleaching bolts of English cloth in buttermilk, spreading it out in the fields to dry in the sun. People raised and harvested thistles, then bundled their prickly heads together to make tools for carding cloth. Whole villages sat out making lace as fast as their fingers could work, just a few children running from one person to the next with a cup of water for them to sip, or a bread-crust to snap at. Farmers whose stables were filled, not with horses, but with painters—young men from France, Savoy, or Italy who sat before easels making copy after copy of land- and sea-scapes and enormous renditions of the Siege of Vienna. These, stacked and bundled and wrapped into cargo-bales, joined the parade bound for Amsterdam.

The flow took them sometimes into smaller cities, where little trade-fairs were forever teeming. Since none of the farmers in this upside-down country grew food, they had to buy it in markets like city people. Jack and Eliza would jostle against rude boers and haggle against farmers’ wives with silver rings on their fingers trying to buy cheese and eggs and bread to eat along their way. Eliza saw storks for the first time, building their nests on chimneys and swooping down into streets to snatch scraps before the dogs could get them. Pelicans she liked, too. But the things Jack marveled at—four-legged chickens and two-headed sheep, displayed in the streets by boers—were of no interest to her. She’d seen better in Constantinople.

In one of those towns they saw a woman walking about imprisoned in a barrel with neck- and arm-holes, having been guilty of adultery, and after this, Eliza would not rest, nor let Jack have peace or satisfaction, until they’d reached the city. So they drove themselves onwards across lands that had been ruined a dozen years before, when William of Orange had opened the sluices and flooded the land to make a vast moat across the Republic and save Amsterdam from the armies of King Looie. They squatted in remains of buildings that had been wrecked in that artificial Deluge, and followed canals north, skirting the small camps where canal-pirates, the watery equivalent of highwaymen, squatted round wheezing peat-fires. Too, they avoided the clusters of huts fastened to the canal-banks, where lepers lived, begging for alms by flinging ballasted boxes out at passing boats, then reeling them in speckled with coins.

One day, riding along a canal’s edge, they came to a confluence of waters, and turned a perfect right angle and stared down a river that ran straight as a bow-string until it ducked beneath the curvature of the earth. It was so infested with shipping that there seemed to be not enough water left to float a nutshell. Obviously it led straight to Amsterdam.

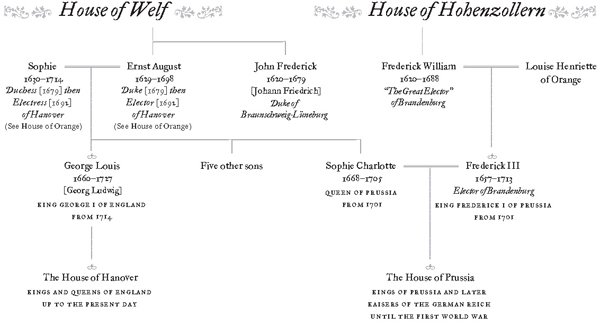

Their escape from Germany (as that mess of Duchies, Electorates, Landgraviates, Margraviates, Counties, Bishoprics, Archbishoprics, and Principalities was called) had taken much longer than Jack had really wanted. The Doctor had offered to take them as far as Hanover, where he looked after the library of the Duchess Sophia* when he wasn’t building windmills atop their Harz silver-mines. Eliza had accepted gratefully, without asking whether Jack might have an opinion on the matter. Jack’s opinion would have been no, simply because Jack was in the habit of going wherever he wished whenever the mood took him. And accompanying the Doctor to Hanover meant that they could not leave Bockboden until the Doctor had settled all of his business in that district.

“WHAT’S HE WASTING TODAY ON?” Jack demanded of Enoch Root one morning. They were riding along a mountain road, followed by a couple of heavy ox-carts. Enoch went on errands like this one every morning. Jack, lacking any other kind of stimulation, had decided to take up the practice.

“Same as yesterday.”

“And that is? Forgive an ignorant Vagabond, but I am used to men of action—so when the Doctor spends all day, every day, talking to people, it seems to me as if he’s doing nothing.”

“He’s accomplishing nothing—that’s very different from doing nothing,” Enoch said gravely.

“What’s he trying to accomplish?”

“He’d persuade the masters of the Duke’s mines not to abandon all of his innovations, now that his latest attempt to sell Kuxen has gone the way of all the others.”

“Well, why should they listen to him?”

“We are going where the Doctor went yesterday,” Enoch said, “and heard what he wanted to from the master of a mine.”

“Beggin’ yer pardon, guv’nor, but that striketh me not as an answer to my question.”

“This entire day will be your answer,” Enoch said, and then looked back, significantly, at a heavy cart following behind them, which was laden with quicksilver flasks packed in wooden crates.

They came to a mine like all the others: schlock-heaps, hand-haspels, furnaces, wheelbarrows. Jack had seen it in the Ore Range and he’d seen it in the Harz, but today (perhaps because Enoch had suggested that there was something to be learned) he saw a new thing.

The shards of ore harvested from the veins growing in the earth, were brought together and dumped out in a pile on the ground, then raked out and beaten up with hammers. The fragments were inspected in the light of day by miners too old, young, or damaged to go down into the tunnels, and sorted into three piles. The first was stone with no silver in it, which was discarded. The second was ore rich in silver, which went straight to the furnaces to be (if what Jack had seen in the Ore Range was any guide) crushed between millstones, mixed with burning-lead, shoveled into a chimney-like furnace blown by great mule-powered bellows, and melted down into pigs of crude silver. The third, which Jack had not seen at Herr Geidel’s mine, was ore that contained silver, but was not as rich as the other. Geidel would have discarded this as not worth the trouble to refine it.

Jack followed a wagon-load of this down the hill to a flat meadow decorated by curious mounds hidden under oiled canvas tarps. Here, men and women were pounding this low-grade ore in big iron mortars and turning the proceeds out into clattering sieves. Boys shook these to sift out powdered ore, then mixed it with water, salt, and the dross from copper-making to produce a sticky clay. This they emptied into large wooden tubs. Then along came an elder, trailed by a couple of stout boys sweating under heavy backloads that looked familiar: they were the quicksilver-flasks that the Doctor had bought in Leipzig, and that Enoch had delivered to them this very morning. The elder stirred through the mud with his hand, checking its quality and consistency, and, if it was right, he’d hug a flask and draw out the wooden bung and tip it, making a bolt of quicksilver strike into the mud like argent lightning. Barefoot boys went to work stomping the mercury into the mud.

Several such vats were being worked at any one time. Enoch explained to Jack that the amalgam had to be mixed for twenty-four hours. Then the vat was upended to make a heap of the stuff on the ground. At this particular mine, there were dozens of such heaps arrayed across the meadow, each one protected from the rain by a canopy of rugged cloth, and each stuck with a little sign scrawled with information about how long it had been sitting there. “This one was last worked ten days ago—it is due,” Enoch told him, reading one of the signs. Indeed, later some of the workers rolled an empty tub up to that pile, shoveled the amalgam into it, added water, and began to work it with their feet again.

Enoch continued to wander about, peeling back canvas to inspect the heaps, and offering suggestions to the elders. Locals had begun filtering out of the woods as soon as visitors had arrived, and were now following him around—greed for knowledge drawing them closer, and fear pushing them back. “This one’s got too much quicksilver,” he said of one, “that’s why it’s black.” But another was the color of bran. More quicksilver was wanted. Most of them were shades of gray, which was apparently desirable—but Enoch thrust his hand into these to check their warmth. Cold ones needed to have more copper dross added, and overly hot ones needed water. Enoch was carrying a basin, which he used to wash samples of the heaps in water until little pools of silver formed in the bottom. One of the heaps, all of a uniform ash color, was deemed ready. Workers shoveled it into wheelbarrows and took it down to a creek, where a cascade had been set up to wash it. The water carried the ashy stuff away as swirling clouds, and left silvery residue. This they packed into conical bags, like the ones used to make sugar-loaves, and hung them up over pots, rows of them dangling like the tits on a sow, except that instead of producing milk they dripped quicksilver, leaving a gleaming semisolid mass inside the bags. This they formed into balls, like boys making snowballs, and put them, a few at a time, into crucibles. Over the top of each crucible they put an iron screen, then flipped the whole thing upside-down and placed it over a like crucible, half-buried in the ground, with water in the bottom, so that the two were fitted rim-to-rim, making a capsule divided in half by the iron screen. Then they buried the whole thing in coal and burned it until it was all red-hot. After it cooled, they raked off the ash and took it all apart to reveal that the quicksilver had been liberated from the balls of amalgam and escaped through the screen, to puddle below, leaving above a cluster of porous balls of pure silver metal all stuck together, and ready to be minted into thalers.

Jack spent most of the ride home pondering what he’d seen. He noticed after a while that Enoch Root had been humming in a satisfied way, evidently pleased with himself for having been able to so thoroughly shut Jack up.

“So Alchemy has its uses,” Enoch said, noting that Jack was coming out of his reverie.

“You invented this?”

“I improved it. In the old days they used only quicksilver and salt. The piles were cold, and they had to sit for a year. But when dross of copper is added, they become warm, and complete the change in three or four weeks.”

“The cost of quicksilver is—?”

Enoch chuckled. “You sound like your lady friend.”

“That’s the first question she’s going to ask.”

“It varies. A good price for a hundredweight would be eighty.”

“Eighty of what?”

“Pieces of eight,” Enoch said.

“It’s important to specify.”

“Christendom’s but a corner of the world, Jack,” Enoch said. “Outside of it, pieces of eight are the universal currency.”

“All right—with a hundredweight of quicksilver, you can make how much silver?”

“Depending on the quality of the ore, about a hundred Spanish marks—and in answer to your next question, a Spanish mark of silver, at the standard level of fineness, is worth eight pieces of eight and six Royals…”

“A PIECE OF EIGHT HAS eight reals—” Eliza said, later, having spent the last two hours sitting perfectly motionless while Jack paced, leaped, and cavorted about her bedchamber relating all of these events with only modest improvements.

“I know that—that’s why it’s called a piece of eight,” Jack said testily, standing barefoot on the sack of straw that was Eliza’s bed, where he had been demonstrating the way the workers mixed the amalgam with their feet.

“Eight pieces of eight plus six royals, makes seventy royals. A hundred marks of silver, then, is worth seven thousand royals…or…eight hundred seventy-five pieces of eight. And the price of the quicksilver needed is—again?”

“Eighty pieces of eight, or thereabouts, would be a good price.”

“So—those who’d make money need silver, and those who’d make silver need quicksilver—and a piece of eight’s worth of quicksilver, put to the right uses, produces enough silver to mint ten pieces of eight.”

“And you can re-use it, as they are careful to do,” Jack said. “You have forgotten a few other necessaries, by the way—such as a silver mine. Mountains of coal and salt. Armies of workers.”

“All gettable,” Eliza said flatly. “Didn’t you understand what Enoch was telling you?”

“Don’t say it!—don’t tell me—just wait!” Jack said, and went over to the arrow-slit to peer up at the Doctor’s windmill, and down at his ox-carts parked along the edge of the stable-yard. Up and down being the only two possibilities when peering through an arrow-slit. “The Doctor provides quicksilver to the mines whose masters do what the Doctor wants.”

“So,” Eliza said, “the Doctor has—what?”

“Power,” Jack finally said after a few wrong guesses.

“Because he has—what?”

“Quicksilver.”

“So that’s the answer—we go to Amsterdam and buy quicksilver.”

“A splendid plan—if only we had money to buy it with.”

“Poh! We’ll just use someone else’s money,” Eliza said, flicking something off the backs of her fingernails.

NOW, STARING DOWN THIS CROWDED canal towards the city, Jack saw, in his mind, a map he’d viewed in Hanover. Sophie and Ernst August had inherited their library, not to mention librarian (i.e., the Doctor), when Ernst August’s Papist brother—evidently, something of a black sheep—had had the good grace to die young without heirs. This fellow must have been more interested in books than wenches, because his library had (according to the Doctor) been one of the largest in Germany at the time of his demise five years ago, and had only gotten bigger since then. There was no place to put it all, and so it only kept getting shifted from one stable to another. Ernst August apparently spent all of his time either fending off King Louis along the Rhine, or else popping down to Venice to pick up fresh mistresses, and never got round to constructing a permanent building for the collection.

In any event, Jack and Eliza had paused in Hanover for a few days on their journey west, and the Doctor had allowed them to sleep in one of the numerous out-buildings where parts of the library were stored. There had been many books, useless to Jack, but also quite a few extraordinary maps. He had made it his business to memorize these, or at least the parts that were finished. Remote islands and continents splayed on the parchment like stomped brains, the interiors blank, the coastlines trailing off into nowhere and simply ending in mid-ocean because no one had ever sailed farther than that, and the boasts and phant’sies of seafarers disagreed.

One of those maps had been of trade-routes: straight lines joining city to city. Jack could not read the labels. He could identify London and a few other cities by their positions, and Eliza helped him read the names of the others. But one city had no label, and its position along the Dutch coast was impossible to read: so many lines had converged on it that the city itself, and its whole vicinity, were a prickly ink-lake, a black sun. The next time they’d seen the Doctor, Jack had triumphantly pointed out to him that his map was defective. The arch-Librarian had merely shrugged.

“The Jews don’t even bother to give it a name,” the Doctor had said. “In their language they just call it mokum, which means ‘the place.’”

From desire, ariseth the thought of some means we have seen produce the like of that which we aim at; and from the thought of that, the thought of means to that mean; and so continually, till we come to some beginning within our own power.

—HOBBES, Leviathan

AS THEY CAME CLOSER to The Place, there were many peculiar things to look at: barges full of water (fresh drinking-water for the city), other barges laden with peat, large flat areas infested with salt-diggers. But Jack could only gawk at these things a certain number of hours of the day. The rest of the time he gawked at Eliza.

Eliza, up on Turk’s back, was staring at her left hand so fixedly that Jack feared she had found a patch of leprosy, or something, on it. But she was moving her lips, too. She held up her right hand to make Jack be still. Finally she held up the left. It was pink and perfect, but contorted into a strange habit, the long finger folded down, the thumb and pinky restraining each other so that only Index and Ring stood out.

“You look like a Priestess of some new sect, blessing or cursing me.”

“D” was all she said.

“Ah, yes, Dr. John Dee, the famed alchemist and mountebank? I was thinking that with some of Enoch’s parlor tricks, we could fleece a few bored merchants’ wives…”

“The letter D,” she said firmly. “Number four in the alphabet. Four is this,” holding up that versatile left again, with only the long finger folded down.

“Yes, I can see you’re holding up four fingers…”

“No—these digits are binary. The pinky tells ones, the ring finger twos, the long finger fours, the index eights, the thumb sixteens. So when the long finger only is folded down, it means four, which means D.”

“But you had the thumb and pinky folded down also, just now…”

“The Doctor also taught me to encipher these by adding another number—seventeen in this case,” Eliza said, displaying her right with the thumb and pinky tip-to-tip. Putting her hand back as it had been, she announced, “Twenty-one, which means, in the English alphabet, U.”

“But what is the point?”

“The Doctor has taught me to hide messages in letters.”

“It’s your intention to be writing letters to this man?”

“If I do not,” she said innocently, “how can I expect to receive any?”

“Why would you want to?” Jack asked.

“To continue my education.”

“Owff!” blurted Jack, and he doubled over as if Turk had kicked him in the belly.

“A guessing-game?” Eliza said coolly. “It’s got to be either: you think I’m already too educated, or: you hoped it would be something else.”

“Both,” Jack said. “You’ve put hours into improving your mind—with nothing to show for it. I’d hoped you had gotten financial backing out of the Doctor, or that Sophie.”

Eliza laughed. “I’ve told you, over and over, that I never came within half a mile of Sophie. The Doctor let me climb a church-steeple that looks down over Herrenhausen, her great garden, so that I could watch while she went out for one of her walks. That’s as close as someone like me could ever come to someone like her.”

“Why bother, then?”

“It was enough for me simply to lay eyes on her: the daughter of the Winter Queen, and great-granddaughter of Mary Queen of Scots. You would never understand.”

“It’s just that you are always on about money, and I cannot see how staring at some bitch in a French dress, from a mile away, relates to that.”

“Hanover is a poor country anyway—it’s not as if they have much money to gamble on our endeavours.”

“Haw! If that’s poverty, give me some!”

“Why do you think the Doctor is going through such exertions to find investors for the silver mine?”

“Thank you—you’ve brought me back to my question: what does the Doctor want?”

“To translate all human knowledge into a new philosophical language, consisting of numbers. To write it down in a vast Encyclopedia that will be a sort of machine, not only for finding old knowledge but for making new, by carrying out certain logical operations on those numbers—and to employ all of this in a great project of bringing religious conflict to an end, and raising Vagabonds up out of squalor and liberating their potential energy—whatever that means.”

“Speaking for myself, I’d like a pot of beer and, later, to have my face trapped between your inner thighs.”

“It’s a big world—perhaps you and the Doctor can both realize your ambitions,” she said after giving the matter some thought. “I’m finding horseback-riding enjoyable but ultimately frustrating.”

“Don’t look to me for sympathy.”

The canal came together with others, and at some point they were on the river Amstel, which took them into the place, just short of its collision with the river Ij, where it had long ago been dammed up by the beaver-like Dutchmen. Then (as Jack the veteran reader of fortifications could see), as stealable objects, lootable churches, and rapable women had accumulated around this Amstel-Dam, those who had the most to lose had created Lines of Circumvallation. To the north, the broad Ij—more an arm of the sea than a proper river—served as a kind of moat. But on the landward side they’d thrown up walls, surrounding Amstel-Dam in a U, the prongs of the U touching the Ij to either side of where the Amstel joined it, and the bend at the bottom of the U crossing the Amstel upstream of the Dam. The dirt for the walls had to come from somewhere. Lacking hills, they’d taken it from excavations, which conveniently filled with ground-water to become moats. But to the avid Dutch there was no moat that could not be put to work as a canal. As the land inside each U had filled up with buildings, newly arrived strivers had put up buildings outside the walls, making it necessary to create new, larger Us encompassing the old. The city was like a tree, as long as it lived surrounding its core with new growth. Outer layers were big, the canals widely spaced, but in the middle of town they were only a stone’s throw apart, so that Jack and Eliza were always crossing over cleverly counter-weighted drawbridges. As they did so they stared up and down the canals, carpeted with low boats that could skim underneath the bridges, and (on the Amstel, and some larger canals) creaking sloops with collapsible masts. Even the small boats could carry enormous loads below the water-line. The canals and the boats explained, then, why it was possible to move about in Amsterdam at all: the torrent of cargo that clogged roads in the countryside was here transferred to boats, and the streets, for the most part, opened to people.

Long rows of five-story houses fronted on canals. A few ancient timber structures still stood in the middle of town, but almost all of the buildings were brick, trimmed with white and painted over with tar. Jack marvelled like a yokel at the sight of barn doors on the fifth story of a building, opening out onto a sheer drop to a canal. A single timber projected into space above to serve as a cargo hoist. Unlike those Leipziger houses, with storage only in the attic, these were for nothing but.

The richest of those warehouse-streets was Warmoesstraat, and when they’d crossed over it they were in a long plaza called Damplatz, which as far as Jack could tell was just the original Dam, paved over. It had men in turbans and outlandish furry hats, and satin-clad cavaliers sweeping their plumed chapeaus off to bow to each other, and mighty buildings, and other features that might have given Jack an afternoon’s gawking. But before he could even begin, some kind of phenomenon on the scale of a War, Fire, or Biblical Deluge demanded his attention off to the north. He turned his face into a clammy breeze and stared down the length of a short, fat canal to discover a low brown cloud obscuring the horizon. Perhaps it was the pall of smoke from a fire as big as the one that had destroyed London. No, it was a brushy forest, a leafless thicket several miles broad. Or perhaps a besieging army, a hundred times the size of the Turk’s, all armed with pikes as big as pine-trees and aflutter with ensigns and pennants.

In the end, it took Jack several minutes’ looking to allow himself to believe that he was viewing all of the world’s ships at one time—their individual masts, ropes, and spars merging into a horizon through which a few churches and windmills on the other side of it could be made out as dark blurs. Ships entering from, or departing toward, the Ijsselmeer beyond, fired rippling gun-salutes and were answered by Dutch shore-batteries, spawning oozy smoke-clouds that clung about the rigging of all those ships and seemingly glued them all into a continuous fabric, like mud daubed into a wattle of dry sticks. The waves of the sea could be seen as slow-spreading news.

Once Jack had a few hours to adjust to the peculiarity of Amsterdam’s buildings, its water-streets, the people’s aggressive cleanliness, their barking language, and their inability to settle on this or that Church, he understood the place. All of its quarters and neighborhoods were the same as in any other city. The knife-grinders might dress like Deacons, but they still ground knives the same way as the ones in Paris. Even the waterfront was just a stupendously larger rendition of the Thames.

But then they wandered into a neighborhood the likes of which Jack had never seen anywhere—or rather the neighborhood wandered into them, for this was a rambling Mobb. Whereas most of Amsterdam was divided among richer and poorer in the usual way, this roving neighborhood was indiscriminately mixed-up: just as shocking to Vagabond Jack as it would be to a French nobleman. Even from a distance, as the neighborhood came up the street towards Jack and Eliza, he could see that it was soaked with tension. They were like a rabble gathered before palace gates, awaiting news of the death of a King. But as Jack could plainly see when the neighborhood had flowed round them and swept them up, there were no palace gates here, nor anything of that sort.

It would have been nothing more than a passing freak of Creation, like a comet, except that Eliza grabbed Jack’s hand and pulled him along, so that they became part of that neighborhood for half an hour, as it rolled and nudged its way among the buildings of Amsterdam like a blob of mercury feeling its way through a wooden maze. Jack saw that they were anticipating news, not from some external source, but from within—information, or rumors of it, surged from one end of this crowd to the other like waves in a shaken rug, with just as much noise, movement, and eruption of debris as that would imply. Like smallpox, it was passed from one person to the next with great rapidity, usually as a brief furious exchange of words and numbers. Each of these conversations was terminated by a gesture that looked as if it might have been a handshake, many generations in the past, but over time had degenerated into a brisk slapping-together of the hands. When it was done properly it made a sharp popping noise and left the palm glowing red. So the propagation of news, rumors, fads, trends, &c. through this mob could be followed by listening for waves of hand-slaps. If the wave broke over you and continued onwards, and your palm was not red, and your ears were not ringing, it meant that you had missed out on something important. And Jack was more than content to do so. But Eliza could not abide it. Before long, she had begun to ride on those waves of noise, and to gravitate towards places where they were most intense. Even worse, she seemed to understand what was going on. She knew some Spanish, which was the language spoken by many of these persons, especially the numerous Jews among them.

Eliza found lodgings a short distance south and west of the Damplatz. There was an alley just narrow enough for Jack to touch both sides of it at one time, and someone had tried the experiment of throwing a few beams across this gap, between the second, third, and fourth stories of the adjoining buildings, and then using these as the framework of a sort of house. The buildings to either side were being slurped down into the underlying bog at differing rates, and so the house above the alley was skewed, cracked, and leaky. But Eliza rented the fourth story after an apocalyptic haggling session with the landlady (Jack, who had been off stabling Turk, only witnessed the final half-hour of this). The landlady was a hound-faced Calvinist who had immediately recognized Eliza as one who was predestined for Hell, and so Jack’s arrival and subsequent loitering scarcely made any impression. Still, she imposed a strict rule against visitors—shaking a finger at Jack so that her silver rings clanked together like links in a chain. Jack considered dropping his trousers as proof of chastity. But this trip to Amsterdam was Eliza’s plan, not Jack’s, and so he did not consider it meet to do any such thing. They had a place, or rather Eliza did, and Jack could come and go via rooftops and drainpipes.

They lived in Amsterdam for a time.

Jack expected that Eliza would begin to do something, but she seemed content to while away time in a coffee-house alongside the Damplatz, occasionally writing letters to the Doctor and occasionally receiving them. The moving neighborhood of anxious people brushed against this particular coffee-house, The Maiden, twice a day—for its movements were regular. They gathered on the Dam until the stroke of noon, when they flocked down the street to a large courtyard called the Exchange, where they remained until two o’clock. Then they spilled out and took their trading back up to the Dam, dividing up into various cliques and cabals that frequented different coffee-houses. Eliza’s apartment actually straddled an important migration-route, so that between it and her coffee-house she was never out of earshot.

Jack reckoned that Eliza was content to live off what they had, like a Gentleman’s daughter, and that was fine with Jack, who enjoyed spending more than getting. He in the meantime went back to his usual habit, which was to spend many days roaming about any new place he came into, to learn how it worked. Unable to read, unfit to converse with, he learned by watching—and here there was plenty of excellent watching. At first he made the mistake of leaving his crutch behind in Eliza’s garret, and going out as an able-bodied man. This was how he learned that despite all of those Hollandgänger coming in from the East, Amsterdam was still ravenous for labor. He hadn’t been out on the street for an hour before he’d been arrested for idleness and put to work dredging canals—and seeing all the muck that came off the bottom, he began to think that the Doctor’s story of how small creatures got buried in river-bottoms made more sense than he’d thought at first.

When the foreman finally released him and the others from the dredge at day’s end, he could hardly climb up onto the wharf for all the men crowded around jingling purses of heavy-sounding coins: agents trying to recruit sailors to man those ships on the Ij. Jack got away from them fast, because where there was such a demand for sailors, there’d be press-ganging: one blunder into a dark alley, or one free drink in a tavern, and he’d wake up with a headache on a ship in the North Sea, bound for the Cape of Good Hope, and points far beyond.

The next time he went out, he bound his left foot up against his butt-cheek, and took his crutch. In this guise he was able to wander up and down the banks of the Ij and do all the looking he wanted. Even here, though, he had to move along smartly, lest he be taken for a vagrant, and thrown into a workhouse to be reformed.

He knew a few things from talking to Vagabonds and from examining the Doctor’s expansive maps: that the Ij broadened into an inland sea called Ijsselmeer, which was protected from the ocean by the island called Texel. That there was a good deep-water anchorage at Texel, but between that island and Ijsselmeer lay broad sandbanks that, like the ones at the mouth of the Thames, had mired many ships. Hence his astonishment at the size of the merchant fleet in the Ij: he knew that the great ships could not even reach this point.

They had driven lines of piles into the bottom of the Ij to seal off the prongs of the U and prevent French or English warships from coming right up to the Damplatz. These piles supported a boardwalk that swung across the harbor in a flattened arc, with drawbridges here and there to let small boats—ferry kaags, Flemish pleyts, beetle-like water-ships, keg-shaped smakschips—into the inner harbor; the canals; and the Damrak, which was the short inlet that was all that remained of the original river Amstel. Larger ships were moored to the outside of this barrier. At the eastern end of the Inner Harbor, they’d made a new island called Oostenburg and put a shipyard there: over it flew a flag with small letters O and C impaled on the horns of a large V, which meant the Dutch East India Company. This was a wonder all by itself, with its ropewalks—skinny buildings a third of a mile long—windmills grinding lead and boring gun-barrels, a steam-house, perpetually obnubilated, for bending wood, dozens of smoking and clanging smithys including two mighty ones where anchors were made, and a small tidy one for making nails, a tar factory on its own wee island so that when it burnt down it wouldn’t take the rest of the yard with it. A whole warehouse district of its own. Lofts big enough to make sails larger than any Jack had ever seen. And, of course, skeletons of several big ships on the slanted ways, braced with diagonal sticks to keep ’em from toppling over, and all aswarm with workers like ants on a whale’s bones.

Somewhere there must’ve been master wood-carvers and gilders, too, because the stems and sterns of the V.O.C. ships riding in the Ij were decorated like Parisian whorehouses, with carved statues covered in gold-leaf: for example, a maiden reclining on a couch with one shapely arm draped over a globe, and Mercury swooping down from on high to crown her with the laurel. And yet just outside the picket of windmills and watch-towers that outlined the city, the landscape of pastures and ditches resumed. Mere yards from India ships offloading spices and calico into small boats that slipped through the drawbridges to the Damrak, cattle grazed.

The Damrak came up hard against the side of the city’s new weigh-house, which was a pleasant enough building almost completely obscured by a perpetual swarm of boats. On the ground floor, all of its sides were open—it was made on stilts like a Vagabond-shack in the woods—and looking in, Jack could see its whole volume filled with scales of differing sizes, and racks and stacks of copper and brass cylinders engraved with wild snarls of cursive writing: weights for all the measures employed in different Dutch Provinces and the countries of the world. It was, he could see, the third weigh-house to be put up here and still not big enough to weigh and mark all of the goods coming in on those boats. Sloops coming in duelled for narrow water-lanes with canal-barges taking the weighed and stamped goods off to the city’s warehouses, and every few minutes a small heavy cart clattered away across the Damplatz, laden with coins the ships’ captains had used to pay duty, and made a sprint for the Exchange Bank, scattering wigged, ribboned, and turbaned deal-makers out of its path. The Exchange Bank was the same thing as the Town Hall, and a stone’s throw from there was the Stock Exchange—a rectangular courtyard environed by colonnades, like the ones in Leipzig but bigger and brighter.

One afternoon Jack came by the Maiden to pick Eliza up at the end of her hard day’s drinking coffee and spending the Shaftoes’ inheritance. The place was busy, and Jack reckoned he could slip in the door without attracting any bailiffs. It was a rich airy high-ceilinged place, not at all tavernlike, hot and close, with clever people yammering in half a dozen languages. In a corner table by a window, where northern light off the Ij could set her face aglow, Eliza sat, flanked by two other women, and holding court (or so it seemed) for a parade of Italians, Spaniards, and other swarthy rapier-carrying men in big wigs and bright clothes. Occasionally she’d reach for a big round coffee-pot, and at those moments she’d look just like the Maid of Amsterdam on the stern of a ship—or for that matter, as painted on the ceiling of this very room: loosely draped in yards of golden satin, one hand on a globe, one nipple poking out, Mercury always behind and to the right, and below her, the ever-present Blokes with Turbans, and feather-bedecked Negroes, presenting tributes in the form of ropes of pearls and giant silver platters.

She was flirting with those Genoese and Florentine merchants’ sons, and Jack could cope with that, to a point. But they were rich. And this was all she did, every day. He lost the power of sight for a few minutes. But in time his rage cleared away, like the clouds of ash washing away from the amalgam, clearing steadily to reveal a pretty gleam of silver under clear running water. Eliza was staring at him—seeing everything. She glanced at something next to him, telling him to look at it, and then she locked her blue eyes on someone across the table and laughed at a witticism.

Jack followed her look and discovered a kind of shrine against the wall. It was a glass-fronted display case, but all gold-leafed and decked out with trumpet-tooting seraphs, as if its niches had been carved to house pieces of the True Cross and fingernail-parings of Archangels. But in fact the niches contained little heaps of dull everyday things like ingots of lead, scraps of wool, mounds of saltpeter and sugar and coffee-beans and pepper-corns, rods and slabs of iron, copper and tin, and twists of silk and cotton cloth. And, in a tiny crystal flask, like a perfume bottle, there was a sample of quicksilver.

“So, I’m meant to believe that you’re transacting business in there?” he asked, once she had extricated herself, and they were out on the Damplatz together.

“You believed that I was doing what, then?”

“It’s just that I saw no goods or money changing hands.”

“They call it Windhandel.”

“The wind business? An apt name for it.”

“Do you have any idea, Jack, how much quicksilver is stored up in these warehouses all around us?”

“I do.”

She stopped at a place where they could peer into a portal of the Stock Exchange. “Just as a whole workshop can be powered by a mill-wheel, driven by a trickle of water in a race, or by a breath of air on the blades of a windmill, so the movement of goods through yonder Weigh-House is driven by a trickle of paper passing from hand to hand in there” (pointing to the Stock Exchange) “and the warm wind that you feel on your face when you step into the Maiden.”

Movement caught Jack’s eye. He imagined for a moment that it was a watch-tower being knocked down by a sudden burst of French artillery. But when he looked, he saw he’d been fooled for the hundredth time. It was a windmill spinning. Then more movement out on the Ij: a tidal swell coming through and jostling the ships. A dredger full of hapless Hollandgänger moved up a canal, clawing up muck—muck that according to the Doctor would swallow and freeze things that had once been quick, and turn them to stone. No wonder they were so fastidious about dredging. Such an idea must be anathema to the Dutch, who worshipped motion above all. For whom the physical element of Earth was too resistant and inert, an annoyance to traders, an impediment to the fluid exchange of goods. In a place where all things were suffused with quicksilver, it was necessary to blur the transition from earth to water, making out of the whole Republic a gradual shading from one to the other as they neared the banks of the Ij, not entirely complete until they got past the sandbanks and reached the ocean at Texel.

“I must go to Paris.”

“Why?”

“Partly to sell Turk and those ostrich plumes.”

“Clever,” she said. “Paris is retail, Amsterdam wholesale—you’ll fetch twice the price there.”

“But really it is that I am accustomed to being the one fluid thing in a universe dumb and inert. I want to stand on the stone banks of the Seine, where here is solid and there is running water and the frontier between ’em is sharp as a knife.”

“As you wish,” Eliza said, “but I belong in Amsterdam.”

“I know it,” Jack said, “I keep seeing your picture.”