The Star Chamber, Westminster Palace

APRIL 1688

For to accuse, requires less eloquence, such is man’s nature, than to excuse; and condemnation, than absolution more resembles justice.

—HOBBES, Leviathan

“HOW DOES THE SAYING GO? ‘All work and no play…a dull boy,” said a disembodied voice. It was the only perception that Daniel’s brain was receiving at the moment. Vision, taste, and the other senses were dormant, and memory did not exist. This made it possible for him to listen with more-than-normal acuteness to the voice, and to appreciate its fine qualities—of which there were many. It was a delicious voice, belonging to an upper-class man who was used to being listened to, and who liked it that way.

“This boy’s lucubrations have made him very dull indeed, he is a very sluggard!” the voice continued.

A few men chuckled, and shifted bodies sheathed in silk. The sounds echoed from a high and hard ceiling.

Daniel’s mind now recollected that it was attached to a body. But like a regiment that has lost contact with its colonel, the body had not received any orders in a long time. It had gone all loose and discomposed, and had stopped sending signals back to headquarters.

“Give him more water!” commanded the beautiful voice.

Daniel heard boots moving on a hard floor to his left, felt blunt pressure against numbed lips, heard the rim of a bottle crack against one of his front teeth. His lungs began to fill up with some sort of beverage. He tried to move his head back but it responded sluggishly, and something cold hit him on the back of the neck hard enough to stop him. The fluid was flooding down his chin now and trickling under his clothes. His whole thorax clenched up trying to cough the fluid out of his lungs, and he tried to move his head forward—but now something cold caught him across the throat. He coughed and vomited at the same moment and sprayed hot humours all over his lap.

“These Puritans cannot hold their drink—really one cannot take them anywhere.”

“Save, perhaps, to Barbados, my Lord!” offered up another voice.

Daniel’s eyes were bleary and crusted. He tried raising his hands to his face, but halfway there each one of them collided with a bar of iron that was projecting across space. Daniel groped at these, but dire things happened to his neck when he did, and so he ended up feeling around them to paw at his eyes and wipe grit and moisture away from his face. He could make out now that he was sitting on a chair in the middle of a large room; it was night, and the place was lit up by only a modest number of candles. The light gleamed from white lace cravats round the throats of several gentlemen who were arranged round Daniel in a horseshoe.

The light wasn’t bright enough, and his vision wasn’t clear enough, to make sense of this ironmongery that was about his neck, so he had to explore that with his hands. It seemed to be a band of iron bent into a neck-ring. From four locations equally spaced around its circumference rods of iron projected outwards like spokes from a wheel-hub, to a radius of perhaps half a yard, where each split into a pair of back-curved barbs, like the flukes of grappling-hooks.

“While you were sleeping off the effects of M. LeFebure’s draught, I took the liberty of having you fitted out with new neckwear,” said the voice, “but as you are a Puritan, and have no use for vanity, I called upon a blacksmith instead of a tailor. You’ll find that this is all the mode in the sugar plantations of the Caribbean.”

The barbs sticking out behind had gotten lodged in the back of the chair when Daniel had unwisely tried to sit forward. Now he gripped the ones in front and pushed himself back hard, knocking the rear ones free. Momentum carried him and the collar back; his spine slammed into the chair and the collar kept moving and tried to shear his head off. He ended up with his head tilted back, gazing almost straight up at the ceiling. His first thought was that candles had somehow been planted up there, or burning arrows shot at random into the ceiling by bored soldiery, but then his eyes focused and he saw that the vault had been decorated with painted stars that gleamed in the candle-light from beneath. Then he knew where he was.

“The Court of Star Chamber is in session—Lord Chancellor Jeffreys presiding,” said another excellent voice, husky with some kind of precious emotion. And what sort of man got choked up over this?

Now just as Daniel’s senses had recovered one at a time, beginning with his ears, so his mind was awakening piece-meal. The part of it that warehoused ancient facts was, at the moment, getting along much better than the part that did clever things. “Nonsense…the Court of Star Chamber was abolished by the Long Parliament in 1641…five years before I was born, or you were, Jeffreys.”

“I do not recognize the self-serving decrees of that rebel Parliament,” Jeffreys said squeamishly. “The Court of Star Chamber was ancient—Henry VII convened it, but its procedures were rooted in Roman jurisprudence—consequently, ‘twas a model of clarity, of effiency, unlike the time-encrusted monstrosity of Common Law, that staggering, cobwebbed Beast, that senile compendium of folklore and wives’ tales, a scabrous Colander seiving all the chunky bits out of the evanescent flux of Society and compacting ‘em into legal head-cheese.”

“Hear, hear!” said one of the other Judges, who apparently felt that Jeffreys had now encompassed everything there was to be said about English Common Law. Daniel assumed they must all be judges, at any rate, and that they’d been hand-picked by Jeffreys. Or, more like it, they’d simply gravitated to him during his career, they were the men that he always saw, whenever he troubled to glance around him.

Another one of them said, “The late Archbishop Laud found this Chamber to be a convenient facility for the suppression of Low Church dissidents, such as your father, Drake Waterhouse.”

“But the entire point of my father’s story is that he was not suppressed—Star Chamber cut his nose and his ears off and it only made him more formidable.”

“Drake was a man of exceptional strength and resilience,” Jeffreys said. “Why, he haunted my very nightmares when I was a boy. My father told me tales of him as if he were a bogey-man. I know that you are no Drake. Why, you stood by and watched one of your own kind be murdered, under your window, at Trinity, by my lord Upnor, twenty-some years ago, and you did nothing—nothing! I remember it well, and I know that you do as well, Waterhouse.”

“Does this sham have a purpose, other than to reminisce about College days?” Daniel inquired.

“Give him a revolution,” Jeffreys said.

The fellow who had poured water into Daniel’s mouth earlier—some sort of armed bailiff—stepped up, grabbed one of the four grappling-hooks projecting from Daniel’s collar, and gave it a wrench. The whole apparatus spun round, using Daniel’s neck as an axle, until he could get his arms up to stop it. A simpler man would have guessed—from the sheer amount of pain involved—that his head had been half sawed away. But Daniel had dissected enough necks to know where all the important bits were. He ran a few quick experiments and concluded that, as he could swallow, breathe, and wiggle his toes, none of the main cables had been severed.

“You are charged with perverting the English language,” Jeffreys proclaimed. “To wit: that on numerous occasions during idle talk in coffee-houses, and in private correspondence, you have employed the word ‘revolution,’ heretofore a perfectly innocent and useful English word, in an altogether new sense, conceived and propagated by you, meaning radical and violent overthrow of a government.”

“Oh, I don’t think violence need have anything to do with it.”

“You admit you are guilty then!”

“I know how the genuine Star Chamber worked…I don’t imagine this sham one is any different…why should I dignify it by pretending to put up a defense?”

“The defendant is guilty as charged!” Jeffreys announced, as if, by superhuman effort, he’d just brought an exhausting trial to a close. “I shan’t pretend to be surprised by the outcome—while you were asleep, we interrogated several witnesses—all agreed you have been using ‘revolution’ in a sense that is not to be found in any treatise of Astronomy. We even asked your old chum from Trinity…”

“Monmouth? But didn’t you chop his head off?”

“No, no, the other one. The Natural Philosopher who has been so impertinent as to quarrel with the King in the matter of Father Francis…”

“Newton!?”

“Yes, that one! I asked him, ‘You have written all of these fat books on the subject of Revolutions, what does the word signify to you?’ He said it meant one body moving about another—he uttered not a word about politics.”

“I cannot believe you have brought Newton into this matter.”

Jeffreys abruptly stopped playing the rôle of Grand Inquisitor, and answered in the polite, distracted voice of the busy man-about-town: “Well, I had to grant him an audience anyway, on the Father Francis matter. He does not know you are here…just as you, evidently, did not know he was in London.”

In the same sort of tone, Daniel replied, “Can’t blame you for finding it all just a bit bewildering. Of course! You’d assume that Newton, on a visit to London, would renew his acquaintance with me, and other Fellows of the Royal Society.”

“I have it on good authority he has been spending time with that damned Swiss traitor instead.”

“Swiss traitor?”

“The one who warned William of Orange of the French dragoons.”

“Fatio?”

“Yes, Fatio de Duilliers.”

Jeffreys was absent-mindedly patting his wig, puzzling over this fragment re Newton. The sudden change in the Lord Chancellor’s affect had engendered, in Daniel, a giddiness that was probably dangerous. He had been trying to stifle it. But now Daniel’s stomach began to shake with suppressed laughter.

“Jeffreys! Fatio is a Swiss Protestant who warned the Dutch of a French plot, on Dutch soil…and for this you call him a traitor?”

“He betrayed Monsieur le comte de Fenil. And now this traitor has moved to London, for he knows that his life is forfeit anywhere on the Continent…anywhere Persons of Quality observe a decent respect for justice. But here! London, England! Oh, in other times his presence would not have been tolerated. But in these parlous times, when such a man comes and takes up residence in our city, no one bats an eye…and when he is seen buying alchemical supplies, and talking in coffee-houses with our foremost Natural Philosopher, no one thinks of it as scandalous.”

Daniel perceived that Jeffreys was beginning to work himself up into another frenzy. So before the Lord Chancellor completely lost his mind, Daniel reminded him: “The real Star Chamber was known for pronouncing stern sentences, and executing them quickly.”

“True! And if this assembly had such powers, your nose would be lying in the gutter, and the rest of you would be on a ship to the West Indies, where you would chop sugar cane on my plantation for the rest of your life. As it stands, I cannot punish you until I’ve convicted you of something in the common-law court. Shouldn’t be all that difficult, really.”

“How do you suppose?”

“Tilt the defendant back!”

The Star Chamber’s bailiffs, or executioners or whatever they were, converged on Daniel from behind, gripped the back of his chair, and yanked, raising its front legs up off the floor and leaving Daniel’s feet a-dangle. His weight shifted from his buttocks to his back, and the iron collar went into motion and tried to fall to the floor. But it was stopped by Daniel’s throat. He tried to raise his hands to take the weight of the iron off his wind-pipe, but Jeffreys’ henchmen had anticipated that: each of them had a spare hand that he used to pin one of Daniel’s hands down to the chair. Daniel could see nothing but stars now: stars painted on the ceiling when his eyes were open, and other stars that zoomed across his vision when his eyes were closed. The face of the Lord Chancellor now swam into the center of this firmament like the Man in the Moon.

Now Jeffreys had been an astonishingly beautiful young man, even by the standards of the generation of young Cavaliers that had included such Adonises as the Duke of Monmouth and John Churchill. His eyes, in particular, had been of remarkable beauty—perhaps this accounted for his ability to seize and hold the young Daniel Waterhouse with his gaze. Unlike Churchill, he had not aged well. Years in London, serving as solicitor general to the Duke of York, then as a prosecutor of supposed conspirators, then Lord Chief Justice, and now Lord Chancellor, had put leaves of lard on him, as on a kidney in a butcher-stall. His eyebrows had grown out into great gnarled wings, or horns. The eyes were beautiful as ever, but instead of gazing out from the fair unblemished face of a youth, they peered out through a sort of embrasure, between folds of chub below and snarled brows above. It had probably been fifteen years since Jeffreys could list, from memory, all the men he had murdered through the judicial system; if he hadn’t lost count while extirpating the Popish Plot, he certainly had during the Bloody Assizes.

At any rate Daniel could not now tear his eyes away from those of Jeffreys. In a sense Jeffreys had planned this spectacle poorly. The drug must have been slipped into Daniel’s drink at the coffeehouse and Jeffreys’s minions must have abducted him after he’d fallen asleep in a water-taxi. But the elixir had made him so groggy that he had failed to be afraid until this moment.

Now, Drake wouldn’t have been afraid, even fully awake; he’d sat in this room and defied Archbishop Laud to his face, knowing what they would do to him. Daniel had been brave, until now, only insofar as the drug had made him stupid. But now, looking up into the eyes of Jeffreys, he recalled all of the horror-stories that had emanated from the Tower as this man’s career had flourished: Dissidents who “committed suicide” by cutting their own throats to the vertebrae; great trees in Taunton decorated with hanged men, dying slowly; the Duke of Monmouth having his head gradually hacked off by Jack Ketch, five or six strokes of the axe, as Jeffreys looked on with those eyes.

The colors were draining out of the world. Something white and fluffy came into view near Jeffreys’s face: a hand surrounded by a lace cuff. Jeffreys had grasped one of the hooks projecting up from Daniel’s collar. “You say that your revolution does not have to involve any violence,” he said. “I say you must think harder about the nature of revolution. For as you can see, this hook is on top now. A different one is on the bottom. True, we can raise the low one up by a simple revolution—” Jeffreys wrenched the collar around, its entire weight bearing on Daniel’s adam’s apple—giving Daniel every reason to scream. But he made no sound other than a pitiable attempt to suck in some air. “Ah, but observe! The one that was high is now low! Let us raise it up then, for it does not love to be low.” Jeffreys wrenched it back up. “Alas, we are back to where we started; the high is high, the low is low, and what’s the point of having a revolution at all?” Jeffreys now repeated the demonstration, laughing at Daniel’s struggle for air. “Who could ask for a better career!” he exclaimed. “Slowly decapitating the men I went to college with! We made Monmouth last as long as ‘twas possible, but the axe is imprecise, Jack Ketch is a butcher, and it ended all too soon. But this collar is an excellent device for a gradual sawing-off, I could make him last for days!” Jeffreys sighed with delight. Daniel could not see any more, other than a few pale violet blotches swimming in turbulent gray. But Jeffreys must have signalled the bailiffs to right the chair, for suddenly the weight of the collar was on his collarbones and his efforts to breathe were working. “I trust I have disabused you of any ludicrous ideas concerning the true nature of revolutions. If the low are to be made high, Daniel, then the high must be made low—but the high like to be high—and they have an army and a navy. ‘Twill never occur without violence. And ‘twill fail given enough time, as your father’s failed. Have you quite learnt the lesson? Or shall I repeat the demonstration?”

Daniel tried to say something: namely to beg that the demonstration not be repeated. He had to because it hurt too much and might kill him. To beg for mercy was utterly reasonable—and the act of a coward. The only thing that prevented him from doing it was that his voice-box was not working.

“It is customary for a judge to give a bit of a scolding to a guilty man, to help him mend his ways,” Jeffreys reflected. “That part of the proceedings is now finished—we move on to Sentencing. Concerning this, I have Bad News, and Good News. ‘Tis an ancient custom to give the recipient of Bad and Good News, the choice of which to hear first. But as Good News for me is Bad for you, and vice versa, allowing you to make the choice will only lead to confusion. So: the Bad News, for me, is that you are correct, the Star Chamber has not been formally re-constituted. ‘Tis just a pastime for a few of us Senior Jurists and has no legal authority to carry out sentences. The Good News, for me, is that I can pronounce a most severe sentence upon you even without legal authority: I sentence you, Daniel Waterhouse, to be Daniel Waterhouse for the remainder of your days, and to live, for that time, every day with the knowledge of your own disgusting cravenness. Go! You disgrace this Chamber! Your father was a vile man who deserved what he got here. But you are a disfigurement of his memory! Yes, that’s right, on your feet, about face, march! Get out! Just because you must live with yourself does not mean we must be subjected to the same degradation! Out, out! Bailiffs, throw this quivering mound of shite out into the gutter, and pray that the piss running down his legs will wash him down into the Thames!”

THEY DUMPED HIM like a corpse in the open fields upriver from Westminster, between the Abbey and the town of Chelsea. When they rolled him out the back of the cart, he came very close to losing his head, as one of the collar-hooks caught in a slat on the wagon’s edge and gave him a jerk at the neck so mighty it was like to rip his soul out of his living body. But the wood gave way before his bones did, and he fell down into the dirt, or at least that was what he inferred from evidence near to hand when he came to his senses.

His desire at this point was to lie full-length on the ground and weep until he died of dehydration. But the collar did not permit lying down. Having it round his neck was a bit like having Drake stand over him and berate him for not getting up. So up he got, and stumbled round and wept for a while. He reckoned he must be in Hogs-den, or Pimlico as men in the real estate trade liked to name it: not the country and not the city, but a blend of the most vile features of both. Stray dogs chased feral chickens across a landscape that had been churned up by rooting swine and scraped bald by scavenging goats. Nocturnal fires of bakeries and breweries shot rays of ghastly red light through gaps in their jumble-built walls, spearing whores and drunks in their gleam.

It could have been worse: they could have dumped him in a place with vegetation. The collar was designed to prevent slaves from running away by turning every twig, reed, vine, and stalk into a constable that would grab the escapee by the nape as he ran by. As Daniel roamed about, he explored the hasp with his fingers and found it had been wedged shut with a carven peg of soft wood which had been hammered through the loops. By worrying this back and forth he was able to draw it out. Then the collar came loose on his neck and he got it off easily. He had a dramatical impulse to carry it over to the river-bank and fling it into the Thames, but then coming to his senses he recollected that there was a mile of dodgy ground to be traversed before he reached the edge of Westminster, and any number of dogs and Vagabonds who might need to be beaten back in that interval. So he kept a grip on it, swinging it back and forth in the darkness occasionally, to make himself feel better. But no assailant came for him. His foes were not of the sort that could be struck down with a rod of iron.

ON THE SOUTHERN EDGE of the settled and civilized part of Westminster, a soon-to-be-fashionable street was under construction. It was the latest project of Sterling Waterhouse, who was now Earl of Willesden, and spent most of his days on his modest country estate just to the northwest of London, trying to elevate the self-esteem of his investors.

One of the people who’d put money into this Westminster street was the woman Eliza, who was now Countess of Zeur. Eliza occupied something like fifty percent of all Daniel’s waking thoughts now. Obviously this was a disproportionate figure. If it’d been the case that Daniel continually come up with new and original thoughts on the subject of Eliza, then he might have been able to justify thinking about her ten or even twenty percent of the time. But all he did was think the same things over and over again. During the hour or so he’d spent in the Star Chamber, he’d scarcely thought of her at all, and so now he had to make up for that by thinking about nothing else for an hour or so.

Eliza had come to London in February, and on the strength of personal recommendations from Leibniz and Huygens, she had talked her way into a Royal Society meeting—one of the few women ever to attend one, unless you counted Freaks of Nature brought in to display their multiple vaginas or nurse their two-headed babies. Daniel had escorted the Countess of Zeur into Gresham’s College a bit nervously, fearing that she’d make a spectacle of herself, or that the Fellows would get the wrong idea and use her as a subject for vivisection. But she had dressed and behaved modestly and all had gone well. Later Daniel had taken her out to Willesden to meet Sterling, with whom she gotten along famously. Daniel had known they would; six months earlier both had been commoners, and now they strolled in what was to become Sterling’s French garden, deciding where the urns and statues ought to go, and compared notes as to which shops were the best places to buy old family heirlooms.

At any rate, both of them now had money invested in this attempt to bring civilization to Hogs-den. Even Daniel had put a few pounds into it (not that he considered himself much of an investor; but British coinage had only gotten worse in the last twenty years, if that was imaginable, and there was no point in keeping your money that way). To prevent the site from being ravaged every night by the former inhabitants (human and non-), a porter was stationed there, in a makeshift lodge, with a large number of more or less demented dogs. Daniel managed to wake all of them up by stumbling over the fence at 3:00 A.M. with his neck half sawn through. Of course the porter woke up last, and didn’t call the dogs off until half of Daniel’s remaining clothes had been torn away. But by that point in the evening, those clothes could not be accounted any great loss.

Daniel was happy just to be recognized by someone, and made up the customary story about having been set upon by blackguards. To this, the porter responded with the obligatory wink. He gave Daniel ale, an act of pure kindness that brought fresh tears to Daniel’s eyes, and sent his boy a-running into Westminster to summon a hackney-chair. This was a sort of vertical coffin suspended on a couple of staves whose ends were held up by great big taciturn men. Daniel climbed into it and fell asleep.

When he woke up it was dawn, and he was in front of Gresham’s College, on the other end of London. A letter was waiting for him from France.

THE LETTER BEGAN,

Is the weather in London still quite dismal? From the vantage point of Versailles, I can assure you that spring approaches London. Soon, I will be approaching, too.

Daniel (who was reading this in the College’s entrance hall) stopped there, stuffed the letter into his belt, and stumbled into the penetralia of the Pile. Not even Sir Thomas Gresham his own self would be able to find his way around the place now, if he should come back to haunt it. The R.S. had been having its way with the building for almost three decades and it was just about spent. Daniel scoffed at all talk of building a new Wren-designed structure and moving the Society into it. The Royal Society was not reducible to an inventory of strange objects, and could not be re-located by transporting that inventory to a new building, any more than a man could travel to France by having his internal organs cut out and packed in barrels and shipped across the Channel. As a geometric proof contained, in its terms and its references, the whole history of geometry, so the piles of stuff in the larger Pile that was Gresham’s College encoded the development of Natural Philosophy from the first meetings of Boyle, Wren, Hooke, and Wilkins up until to-day. Their arrangement, the order of stratifications, reflected what was going on in the minds of the Fellows (predominantly Hooke) in any given epoch, and to move it, or to tidy it up, would have been akin to burning a library. Anyone who could not find what he needed there, didn’t deserve to be let in. Daniel felt about the place as a Frenchman felt about the French language, which was to say that it all made perfect sense once you understood it, and if you didn’t understand it, then to hell with you.

He found a copy of the I Ching in about a minute, in the dark, and carrying it over to where rosy-fingered Dawn was clawing desperately at a grime-caked window, found the hexagram 19, Lin, Approach. The book went on at length concerning the bottomless significance of this symbol, but the only meaning that mattered to Daniel was 000011, which was how the pattern of broken and unbroken lines translated to binary notation. In decimal notation this was 3.

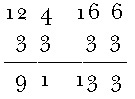

It would have been perfectly all right for Daniel to have crawled up to his garret atop the College and fallen asleep, but he felt that having been stupefied with opium for a night and a day ought to have enabled him to catch up on his sleep, and events in the Star Chamber and later in Hogs-den had got him rather keyed up. Any one of these three things sufficed to prevent sleep: the raw wounds around his neck, the commotion of the City coming awake, and his beastly, uncontrollable lust for Eliza. He went up-stairs to a room that was optimistically called the Library, not because it had books (every room did) but because it had windows. Here he spread out Eliza’s letter on a table all streaked and splotched with disturbing stains. Next to it he set down a rectangle of scrap paper (actually a proof of a woodcut intended for Volume III of Newton’s Principia Mathematica). Examining the characters in Eliza’s letter one by one, he assigned each to either the 0 alphabet or the 1 alphabet and wrote a corresponding digit on the scrap paper, arranging them in groups of five. Thus

DOCTO RWATE RHOUS E

01100 00100 10000 0

The first group of binary digits made the number 12, the second 4, the next 16, and the one after that 6. So writing these out on a new line, and subtracting a 3 from each, he got

Which made the letters I A M C

The light got better as he worked.

Leibniz was building a splendid library in Wolfenbüttel, with a high rotunda that would shed light down onto the table below…

His forehead was on the table. Not a good way to work. Not a good way to sleep either, unless your neck was so torn up as to make lying down impossible, in which case it was the only way to sleep. And Daniel had been sleeping. The pages under his face were a sea of awful light, the unfair light of noon.

“Truly you are an inspiration to all Natural Philosophers, Daniel Waterhouse.”

Daniel sat up. He was stiff as a grotesque. He could feel and hear the scab-work on his neck cracking. Seated two tables away, quill in hand, was Nicolas Fatio de Duilliers.

“Sir!”

Fatio held up a hand. “I do not mean to disturb you, there is no need for—”

“Ah, but there is a need for me to express my gratitude. I have not seen you since you saved the life of the Prince of Orange.”

Fatio closed his eyes for a moment. “‘Twas like a conjunction of planets, purely fortuitous, reflecting no distinction on me, and let us say no more of it.”

“I learned only recently that you were in town—that your life was in danger so long as you remained on the Continent. Had I known as much earlier, I’d have offered you whatever hospitality I could—”

“And if I were worthy of the title of gentleman, I’d have waited for that offer before making myself at home here,” Fatio returned.

“Isaac of course has given you the run of the place and that is splendid.”

Daniel now noticed Fatio gazing at him with a penetrating, analytical look that reminded him of Hooke peering through a lens. From Hooke it was not objectionable, somehow. From Fatio it was mildly offensive. Of course Fatio was wondering how Daniel knew that he’d been hobnobbing with Isaac. Daniel could have told him the story about Jeffreys and the Star Chamber, but it would only have confused matters more.

Fatio now appeared to notice, for the first time, the damage to Daniel’s neck. His eyes saw all, but they were so big and luminous that it was impossible for him to conceal what he was gazing at; unlike the eyes of Jeffreys, which could secretly peer this way and that in the shadow of their deep embrasures, Fatio’s eyes could never be used discreetly.

“Don’t ask,” Daniel said. “You, sir, suffered an honorable wound on the beach. I’ve suffered one, not so honorable, but in the same cause, in London.”

“Are you quite all right, Doctor Waterhouse?”

“Splendid of you to inquire. I am fine. A cup of coffee and I’ll be as good as new.”

Whereupon Daniel snatched up his papers and repaired to the coffee-house, which was full of people and yet where he felt more privacy than under the eyes of Fatio.

The binary digits hidden in the subtleties of Eliza’s handwriting became, in decimal notation,

4 16 6 18 16 12 17 10

which when he subtracted 3 from each (that being the key hidden in the I Ching reference) became

9 1 13 3 15 13 9 14 7… which said,

I AM COMING…

THE FULL DECIPHERMENT took a while, because Eliza provided details concerning her travel plans, and wrote of all she wanted to do while she was in London. When he was finished writing out the message he came alive to the fact that he had sat for a long time, and consumed much coffee, and needed to urinate in the worst way. He could not recall the last time he had made water. And so he went back to a sort of piss-hole in the corner of the tiny court in back of the coffeehouse.

Nothing happened, and so after about half a minute he bent forward as if bowing, and braced his forehead against the stone wall. He had learned that this helped to relax some of the muscles in his lower abdomen and make the urine come out more freely. That stratagem, combined with some artful shifting of the hips and deep breathing, elicited a few spurts of rust-colored urine. When it ceased to work, he turned round, pulled his garments up around his waist, and squatted to piss in the Arab style. By shifting his center of gravity just so, he was able to start up a kind of gradual warm seepage that would provide relief if he kept it up for a while.

This gave him lots of time to think of Eliza, if spinning phant’sies could be named thinking. It was plain from her letter that she expected to visit Whitehall Palace. Which signified little, since any person who was wearing clothes and not carrying a lighted granadoe could go in and wander about the place. But since Eliza was a Countess who dwelt at Versailles, and Daniel (in spite of Jeffreys) a sort of courtier, when she said she wanted to visit Whitehall it meant that she expected to stroll and sup with Persons of Quality. Which could easily be arranged, since the Catholic Francophiles who made up most of the King’s court would fall all over themselves making way for Eliza, if only to get a look at the spring fashions.

But to arrange it would require planning—again, if the dreaming of fatuous dreams could be named planning. Like an astronomer plotting his tide-tables, Daniel had to project the slow wheeling of the seasons, the liturgical calendar, the sessions of Parliament and the progress of various important people’s engagements, terminal diseases, and pregnancies into the time of the year when Eliza was expected to show up.

His first thought had been that Eliza would be here at just the right time: for in another fortnight the King was going to issue a new Declaration of Indulgence that would make Daniel a hero, at least among Nonconformists. But as he squatted there he began to count off the weeks, tick, tick, tick, like the drops of urine detaching themselves one by one from the tip of his yard, and came aware that it would be much longer before Eliza actually got here—she’d be arriving no sooner than mid-May. By that time, the High Church priests would have had several Sundays to denounce Indulgence from their pulpits; they’d say it wasn’t an act of Christian toleration at all, but a stalking-horse for Popery, and Daniel Waterhouse a dupe at best and a traitor at worst. Daniel might have to go live at Whitehall around then, just to be safe.

It was while imagining that—living like a hostage in a dingy chamber at Whitehall, protected by John Churchill’s Guards—that Daniel recalled another datum from his mental ephemeris, one that stopped up his pissing altogether.

The Queen was pregnant. To date she’d produced no children at all. The pregnancy seemed to have come on more suddenly than human pregnancies customarily did. Perhaps they’d been slow to announce it because they’d expected it would only end in yet another miscarriage. But it seemed to have taken, and the size of her abdomen was now a matter of high controversy around Whitehall. She was expected to deliver in late May or early June—just the same time that Eliza would be visiting.

Eliza was using Daniel to get inside the Palace so that she, Eliza, could know as early as possible whether King James II had a legitimate heir, and adjust her investments accordingly. This should have been as obvious as that Daniel had a big stone in his bladder, but somehow Daniel managed to finish what he was doing and go back into the coffee-house without becoming aware of either.

The only person who seemed to understand matters was Robert Hooke, who was in the same coffee-house. He was talking, as usual, to Sir Christopher Wren. But he had been observing Daniel, this whole time, through an open window. He had the look on his face of a man who was determined to speak plainly of unpleasant facts, and Daniel managed to avoid him.