THE LIVING SITES

The fortified city at peace

In Ancient China the peasants had to stay in their hamlets while their lords and their followers lived within the cheng, but in the absence of town charters or even a code of civil law the citizens of a fortified town or city enjoyed little civic liberty, nor would the scholar-officials who ruled the roost tolerate any form of private enterprise. Towns did not therefore become a magnet for the population as in the West. Rebels chose to take refuge in villages, and we frequently hear of a rebellion beginning with an attack on a town, rather than rising within the town itself.

Within the city or town the lives of its inhabitants were – theoretically at least – strictly controlled, a matter given physical expression in the medieval period when the insides of towns and cities were squared off into the wards called fang, which were then subdivided into alleyways. These wards could be closed off at night for security. Until AD 636 the ward gates of Tang Chang’an were opened at dawn to the shouts of the military patrols. Centres of officialdom were separated from the lower orders by further walls, and the Tang Penal Code promised 75 blows for trespassing on ramparts, the inner enclosures or even the low walls separating the wards. But towards the end of the Tang dynasty the expansion of trade and consequent increase in population made it impossible to divide up the inhabitants as they had once been. There was consequently much more freedom of movement, and nocturnal markets were even held. Kaifeng in the 12th century and Hangzhou in the 13th (as so memorably described by Marco Polo) were very lively places where dwelt disreputable people such as actors, singers, prostitutes, jugglers and storytellers. Trade was conducted with a wide variety of food being sold and exotic goods being brought from afar.

|

THE TRIPLE SOUTHERN GATE OF NANJING, AD 1587 |

The Zhonghuamen, the southern gate of Nanjing, is the finest, and probably the largest, example of a fortified gate complex in China. Opening on to the Qinhuai River, when seen from this angle it is impressive only in terms of its bulk, which is a rectangular structure 118.5m wide and 21.5m high topped with battlements. It is only when one crosses the river bridge and enters the dark tunnel that its true scale becomes apparent, because it is pierced with tunnels and dark rooms. Yet one must now pass through no less than three more gated areas before entering the city, necessitating a total walk of about 1.5km. Each of these three inner gates had impressive towers, destroyed by the Japanese and recently restored. No less impressive are the two ramps that flank the gate complex to give access to the walls from inside the city.

Along the River during the Qingming Festival is the title of a famous scroll painting which is believed to depict life in Kaifeng. This is a modern copy, somewhat reduced from the coverage of the original. Just inside the gateway is the office of a professional scribe, while next door is a bow maker.

The fortified city in times of war

When war loomed, the paternalism and social control that was applied to the civilian population in peacetime became even more intrusive. This was largely because it was taken for granted that the poorer members of society would pose the greatest problems of loyalty and service. Simply put, the poor would either run away or be a burden, and might even cooperate with a successful enemy by leading plunderers to the homes of the rich and looting their own share. One ancient authority is quoted as saying that if a town was besieged then one should first look to the interior situation and only then give consideration to the enemy dispositions.

In times of war the cities, having acted as permanent camps to house warriors, became also places of refuge: temporary strongholds for the entire agricultural population. A city may have had a double rampart but the fields extended right into the town, making evacuation of the countryside less of a problem than it might have been. Such a situation whereby everyone without exception had been hurriedly brought within the city walls allowed of course for the unwanted presence of spies and fifth columnists. Itinerant tradesmen and vagrants were particularly suspect in this regard. The preventative measures to be adopted included the issuing of identification tags and the control of access through designated gates manned by officials with a good memory for faces. Yet the most important means for weeding out spies was by the normal surveillance exercised by groups of ten families over their neighbours. Any innkeeper or even the abbot of a monastery found to have a suspicious person on his premises would be punished.

In general, the successful maintenance of civilian morale, law and food supplies during a siege situation required the complete opposite to the principle of carrying on as normal. Family parties and celebration were banned. Tight night-time curfews were imposed. Magicians and fortune tellers, who would be ideal targets for gossip and the planting of false rumours, were strictly controlled, as was any over-indulgence in alcohol that might cause tongues to be loosened.

As to the positive contribution that the beleaguered citizens might make to the war effort none was more important than the prevention, detection and extinguishing of fires. With many buildings made of wood with thatched roofs even an accidental fire during peacetime could be devastating. In Hangzhou in AD 1341 a fire destroyed 15,755 buildings with the loss of 74 lives and the making homeless of 10,797 families. In a siege situation whereby fire and explosives could be launched into a city by catapult, or even small incendiaries taken in by the ingenious use of birds, fire prevention was of the highest priority. Water supplies were usually limited during a siege, and might consist of little more than large jars placed on the streets. For this reason a civilian fire brigade was a necessity, and every city quarter was required to supply a crew of 40 fire fighters, whose duties were closely delineated. The first ten would use hooks to demolish the burning building and anything vulnerable adjacent to it to create a fire break. Ten more men filled the buckets, five carried the water and five more used the water to put the fire out. The remaining five patrolled the streets round about to guard against looting. Special precautions were taken in the case of gunpowder storage. Gunpowder was kept in earthenware jars covered in clay in holes dug into the earth near each city gate. The water stores near the gunpowder magazines were guarded by soldiers, and anyone approaching them was treated as potentially hostile.

The greatest fear of any defending general was that the siege would be so prolonged that his food supplies ran out before either a relieving army appeared or the besieging army abandoned the effort because of a similar shortage of food. At Fengtian in AD 783 men were lowered by ropes from the city walls by night to go scavenging because it was important that the garrison should be well fed and kept warm. For women and children it was sufficient just for them to avoid starvation, and in three extreme cases starving garrisons appear to have resorted to cannibalism. An emissary sent out to the besieging Chu forces around the Song capital in 593 BC during the Spring and Autumn Period reported that ‘In the city we are exchanging our children and eating them, and splitting up their bones for fuel’. This of course may have been a falsehood to make the besiegers think that the city would never surrender, as may have been the serious charge of cannibalism laid at the door of a wicked anti-Sui rebel leader at the time of the founding of the Tang dynasty. He allegedly forced communities under his control to supply women and children with which to feed his troops, and was quite proud of the fact. ‘As long as there are still people in the other states’, he boasted, ‘what have we to worry about?’

A fire in a city as the result of a siege appears in this painting in a temple in Pingyao. Fire was a constant preoccupation of the defenders of a besieged city.

A much more reliable account of cannibalism concerns the siege of Suiyang in AD 757, where the heroic Zhang Xun, who was put to death when the city fell after a siege of ten months, is believed to have instituted cannibalism as a planned and organized response to starvation. The city had been low on supplies even when the siege began, and before long those sheltering within its walls had augmented their meagre grain supplies with paper, tree bark and tea leaves. When all the horses had been eaten the soldiers consumed all the rats and birds that they could catch, and when these ran out Zhang Xun ordered them to kill and eat the civilian population, beginning first with the women, and when there were no women left to eat old men and young boys. To set an example Zhang Xun, whose own wife and children were not inside the city, sacrificed his favourite concubine and made the soldiers eat her flesh. had he managed to hold out for just a few days more using these appalling methods Suiyang would have been relieved by a fast approaching army, and subsequent events were to prove that Zhang Xun’s desperate measures to defend Suiyang made an enormous contribution to the eventual Tang victory. Condemnation of Zhang Xun was therefore somewhat muted, and more sympathy was expressed for the men forced to eat human flesh than those who were unfortunate enough to be eaten.

Military personnel and the siege situation

A city’s standing army would be preoccupied during peacetime with the tedious business of keeping watch from the battlements. Small considerations such as the supply of fruit and iced drinks during summer and the provision of umbrellas against the sun’s heat made the task more bearable. In winter warm clothing and soup similarly kept morale at an acceptable level. Not surprisingly, during a siege their responsibilities became much more acute, and military discipline was enforced every bit as strictly as the control of the civilian population. For example, messages from the enemy sent as arrow letters were not to be opened but should be taken directly to the commanding officer, nor should anyone spontaneously sound a trumpet or raise a flag in case this should be a signal to the enemy. At the very least this would interfere with the precise orders given concerning the issuance of warnings of attack. These would come from observation towers on the wall or from detached forward lookout posts and consist of flags by day or cannon shots and lanterns by night. When such signals were spotted the order was given to reinforce the walls.

The military preparations that the garrison of a Chinese fortified city might take to be ready for a siege started long before the enemy actually came into sight and complemented the civilian measures. The first need was to block his access, particularly along roads, which might be sown with caltrops, four-pointed metal spikes arranged in a tetrahedron shape so that they always landed with one spike pointing upwards. This was done by the Jin when the Mongols approached Beijing in AD 1211. More sophisticated forms of roadblocks consisted of collapsible fences or traps, or old sword blades mounted on boards. A later version was called an ‘earth stopper’, a flat wooden board into which barbed nails were hammered. A more subtle device was the use of dummy soldiers made of straw and bedecked with flags, to make the enemy think that the garrison was much larger than it actually was.

Plan of the rammed earth city walls of Datong. Several sections still survive. (After Ishihara Heizo)

When the enemy attacked, the garrison, of course, should always stand firm, and even during a fire soldiers were strictly forbidden to leave their posts on the walls. These posts were strictly defined by the number of men spread between the number of openings on the battlements, arranged in groups of five under a leader within larger unit lengths of 25 and 100, each subdivision being identified by a flag using a Chinese ideograph in an alphabetical arrangement. No one was allowed to move more than five paces from his post, and even a group leader who strayed into the adjacent set of battlements might be decapitated. Silence was everywhere enforced. Conversation had to be whispered, and people summoned by their officers just by waving a hand. The guard units would work an eight-hour shift on wall duty or even a 12-hour shift if numbers were restricted, but in a wall crew of five men four were permitted to sleep at night with one standing on sentry duty. Temporary shelters were built against the weather, but no one was allowed to leave his post to collect food. Instead two meals were brought up by carriers onto the walls every day between 07.00 and 09.00 and between 15.00 and 17.00. During enemy attacks food was hoisted up on to the walls using ropes.

Hand-held weapons such as axes, maces, hammers, halberds and flails were piled up and kept ready for destroying the enemy’s scaling ladders. One large iron latrine bucket was supplied for every 25 men. During attacks the bucket would be heated and the contents ladled onto the heads of assault parties. Otherwise small stones would be dropped onto individual attackers and bigger boulders used to crush scaling ladders and other siege devices. Some stones might be tied by ropes so that they could be used again, but more common were the ingenious spiked cylinders that could be rolled down the outer surfaces of the walls to clear them of attackers, or the massive spiked boards on chains that crushed opponents in a similar way. Yet on many occasions the defenders on a city wall had to face some formidable siege engines and ingenious siege techniques. These ranged from the mundane, such as ramming, mining and missile bombardment, to the bizarre use of herds of oxen to the tails of which were attached burning brands. Their use is recorded for the year 279 BC when Tian Dan, the general of the state of Qi, was besieged inside the city of Jimo. He is said to have broken the siege by taking a herd of 1,000 oxen, fitting sharp daggers on their horns and reeds soaked in oil to their tails and sending them off in the direction of the siege lines. Many years later at the siege of De’an in AD 1132 by the Jin, the Song defenders used a single fire ox to add to the impact of their sortie out of the city with fire lances.

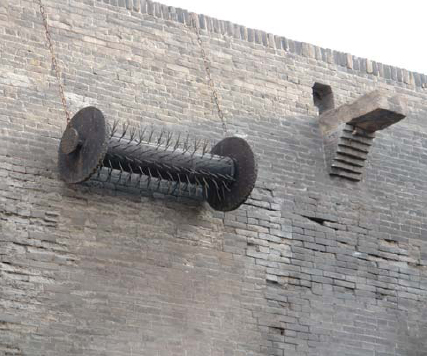

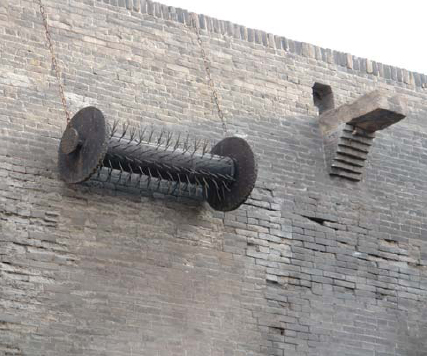

This spiked cylinder and water spout lie on the inner wall of a wengcheng courtyard inside the western gate of Pingyao. The cylinder would be rolled down the wall to clear it of scaling ladders.

The restored south-eastern tower of Beijing, which provided the corner defence in this part of the inner city walls.

Fire was also spread by more conventional means. Pi li pao were exploding fire bombs thrown by catapult. They had casings made from many layers of stiffened paper and were filled with gunpowder and pieces of broken porcelain or iron to inflict personal injury. A larger and clumsier version of a soft-case bomb bore a name that indicated that it was the match for ‘ten thousand enemies’. The housing of the ten thousand enemies’ bomb was of clay, and the whole was enclosed in a cuboid wooden framework or a wooden tub so that the missile did not break before its fuse detonated the explosive. The reason for this is that the ten thousand enemies was neither thrown by a rope sling nor projected from a trebuchet, but simply dropped over the battlements of a castle, and there is a well-known illustration showing how the resulting explosion could blow the besiegers to pieces. ‘The force of the explosion spins the bomb round in all directions, but the city walls protect one’s own men from its effects on that side, while the enemy’s men and horses are not so fortunate,’ says a passage dating from the end of the Ming dynasty.

Unlike the soft-casing thunderclap bombs, the zhen tian lei (thunder-crash bombs or, more literally ‘heaven shaking thunder’) killed people by the shattering of their metal cases and destroyed objects by the increased force of the explosion that is implied by the dramatically enhanced name. The introduction of thunder-crash bombs is credited to the Jin, and their first recorded use in war dates from the siege by the Jin of the Southern Song city of Qizhou in AD 1221. The list of siege weapons used at Qizhou by the besiegers was an eclectic mix of the primitive and the modern, ranging from Greek Fire projectors and expendable birds carrying small incendiaries, to these new exploding cast iron bombs. They were shaped like a bottle gourd with a small opening, and were made from cast iron about two inches thick. The fragments produced when the bombs exploded caused great personal injury, and one Southern Song officer was blinded in an explosion which wounded half a dozen other men.

There were of course occasions when an enemy would capture a section of the walls and fighting would begin in the streets, so this was taken into consideration in defence planning. If the city possessed an inner and an outer wall then the enemy could be trapped between the two. Pitfalls were dug and roadblocks set up, particularly on the approaches to sensitive areas such as gunpowder stores and granaries, as such places would be prime targets. One authority recommends that in the case of a sizeable incursion the civilians should be encouraged to flee the city. Booby traps could be arranged for the incoming enemy, as was done in AD 1277 when Guilin in Guangxi province, one of the last outposts of Southern Song resistance to the Mongols, lay under siege. When the main tower fell a truce was arranged so that the garrison could receive supplies prior to an honourable surrender. During the interregnum some Mongol soldiers climbed up on to the now undefended walls, when suddenly there was an enormous explosion which brought down the wall and the Mongols with it. The Southern Song defenders had prepared a huge bomb at its foundations, and had ignited it at just the right moment.