Chapter 2

I have read my books by many lights, hoarding their beauty, their wit or wisdom against the dark days when I would have no book, nor a place to read.

—Louis L’Amour

Andrews took Nora’s elbow and helped her to her feet. He kept holding on after she stood up, and for a long moment, they both gazed down at Lucille’s body.

“Did you know?” he asked softly. “That she lived like this?”

Nora glanced up the staircase. There were stacks of books on every step. Clothes were draped on top of the books, as were linens, hangers, shoes, tissue boxes, food containers, and more.

“I had no idea,” she said.

Andrews followed her gaze. “She kept that path next to the railing clear, but it’s so narrow. If her foot caught on the edge of one of those book piles, she could easily trip. Honestly, it’s surprising she didn’t lose her balance before now.”

“But she begged for help,” Nora protested. “She answered the phone and begged for help. Then she told me it was too late. I didn’t get to her soon enough.”

“I need to know everything that happened, but not here. Come outside with me.” He put a hand on Nora’s back and steered her toward the dining room.

This room, like the center hallway and staircase, was also a repository of books, clothes, and miscellaneous household items. It looked like a tornado had ripped through the house, picked up everything Lucille owned, and deposited the whole mess right back where it came from.

Outside Vanderbilt’s library at Biltmore, Nora had never seen so many books in someone’s home. Most of the piles were waist-high. Other stacks were over six feet tall. Nora didn’t know if there was a dining table under the mound of old paperbacks that rose toward the ceiling like a cresting wave, but it had to be stronger than Atlas to bear the weight of a thousand romance novels.

The path leading to the kitchen was lined by encyclopedia sets. There were blue ones, black ones, brown ones, and red ones, stacked without any sense of order. Volume 14 from one set was sandwiched between Volumes 2 and 9 from two other sets.

“My gran had the same ones,” Andrews said, pointing at a pile of red books. “She was so proud of them, even though they were all missing pages. Turns out, Gran ripped out entries from every volume. She said certain people didn’t deserve to be in the Encyclopedia Britannica, so she took them out.”

Something cracked under Nora’s foot. The noise startled her, and she jerked sideways, knocking into a tower of encyclopedias. They wobbled precariously, but she pressed the length of her body against them, holding them in a lover’s embrace to keep them from falling.

When she raised her foot, she saw that she’d stepped on a plastic water bottle.

“This place is a minefield,” said Andrews. “Let’s get you outside.”

They picked their way through the dining room and into the kitchen. They’d just entered the cramped and dirty space when two men in EMT uniforms appeared in the boot room.

“Hey, Andrews. Where’s our patient?” asked the older of the two men.

“Let Ms. Pennington get outside. Then I’ll show you,” said Andrews.

The EMT gave Nora a once-over. “You okay, ma’am?”

“I just need some water. I have some in my truck.” Eager to take a breath of fresh air, she brushed past the EMT. “If Andrews needs to talk to me, that’s where I’ll be.”

“Is your truck parked out front? The one with all the books painted on it?” asked the younger man.

Nora nodded.

He gestured toward the dining room. “She buy all these books from you?”

The hint of accusation in his tone nettled Nora. “No. I brought her a bag a few times a month, but she sold books back to me too. I have no idea where all of these came from.”

“You never asked her?” the man pressed.

“I didn’t see them because I’ve never been inside. If I knew she was living like this . . .”

She let the thought dangle because the truth was, she had no clue what she would’ve done other than share her concerns with Grant. He would’ve contacted social services. He would’ve followed up with Lucille Wynter’s caseworker. He would’ve used all of his connections to ensure she got the help she needed.

Why didn’t you do something? taunted her guilty conscience.

The answer wasn’t a pretty one. Nora had convinced herself that she hadn’t questioned Lucille about the holes in her sweater or the spider web crack in her reading glasses because she didn’t want to upset the old woman, but the truth was, she didn’t ask because it was easier not to know.

I brought her cookies I didn’t bake. Socks I didn’t knit. And books. I thought they’d ease her loneliness. I thought they were enough.

The older paramedic gazed into the dining room and whistled. “Looks like Ms. Wynter tried to wall herself in. I used to make forts out of junk when I was a kid. I thought it would keep the monsters out.” He turned back to Nora and said, “We’ll take good care of her. You go get that water.”

Monsters, Nora thought as she waded through the soupy air.

Inside her truck, she put the windows down and drank her tepid water. The ambulance had blocked her in, and when she realized she wouldn’t be going anywhere soon, she folded herself over the steering wheel, rested her head against her arms, and closed her eyes.

In the silence, she considered the EMT’s words: “Looks like Ms. Wynter tried to wall herself in.”

Lucille was afraid to go outside. Nora already knew that, but she had no idea why Lucille had turned her home into a death trap in an effort to feel safe.

Nora had watched dozens of documentaries about hoarding, and in every episode, the hoarder could always go back in time and pinpoint the moment when their need to accumulate stuff began to outweigh all other needs.

Their behavior was often a result of trauma, and many of the hoarders felt compelled to surround themselves with mountains of things as a coping mechanism. The chaos in their homes became a reflection of the chaos in their minds, and Nora felt sorry for every one of these people. At the same time, she felt a voyeuristic fascination watching these shows. She was riveted by the extent of their hoards and by how they continued to add to their collection despite protests from family, friends, landlords, and neighbors.

She knew these shows were scripted and carefully edited, but the pain in the hoarders’ eyes was always genuine. Like Lucille Wynter, they’d used things as a means of separating themselves from the rest of the world. In their labyrinth of material goods, they thought the monsters couldn’t find them.

Except the monsters were already inside.

The thought made Nora feel itchy, so she grabbed her water bottle and wandered into the backyard to wait for Andrews.

A round cement table sat in the middle of a brick patio overrun with weeds. Nora sat on one of the attached bench seats and stared at the gurney parked at the bottom of the stairs leading to the boot room.

She wanted to call Grant, but he was having a beer with a friend he saw only a few times a year and she didn’t want to ruin their time together. She could tell him later, after he came home smelling of smokehouse ribs and onion rings, the traces of laughter still lingering in his eyes.

A car door slammed, and minutes later, Nora heard shoes crunching over gravel.

When Deputy Paula Hollowell rounded the corner of the house, a soft groan wheezed like a deflating balloon through Nora’s lips.

Hollowell darted a glance at the gurney parked outside the boot room before marching over to Nora. She put her hands on her hips and smirked. “Well, well. What have we here?”

It was such a ridiculous B-movie line that Nora had to suppress the urge to roll her eyes. Instead, she gestured toward the back of the house and said, “Andrews is inside.”

“I hear you called it in. What happened?”

Nora wasn’t inclined to give Hollowell more than a quick sketch, so she explained how her concern for Lucille’s welfare had led to her entering Wynter House and finding Lucille at the bottom of the stairs.

“You kicked in the woman’s door?” Hollowell raked her gaze over Nora’s legs. “Are you working out now?”

Seeing a grown woman channel a playground bully would have been laughable if that woman wasn’t wearing a badge and carrying a gun and a Taser.

Nora had disliked the newest member of the Miracle Springs Sheriff’s Department from the moment they’d met. The feeling was clearly mutual.

Hollowell had burgundy hair, deep-set eyes, and a changeable face. She treated most women with either coldness or derision and didn’t have a single female friend. When she was around men, however, she dropped her haughty glare and softened her entire demeanor. She was warm, jocular, and occasionally flirty. Her male coworkers had quickly accepted her into the fold, while the women at the department kept their distance.

Hollowell was one of the younger deputies who’d been hired to replace the vacancy left by the previous K9 officer. She came to Miracle Springs with her own partner, a black German shepherd named Rambo, and when the pair walked the streets, people gave them a wide berth

Nora liked dogs well enough, but with a handler like Hollowell, Rambo made her nervous.

Hooking her thumbs through her utility belt, Hollowell glared down at Nora. “This is what I heard from dispatch. You broke into an old woman’s house because she didn’t answer her phone and, after illegally entering her home, you found her dead at the bottom of the stairs?”

“She asked for help. I tried to give it to her, but I was too late.”

Hollowell put her foot on the bench, inches away from Nora’s hand, and dusted a blade of grass off the toe of her polished boot.

“What really happened? Did the old lady owe you money? Or were you hoping to get your hands on some of her books? I mean, you must’ve known all about her treasures.” Hollowell straightened. “Maybe she was gone by the time you reached her or maybe, once you realized she was in a bad way, you just let nature take its course. You had a good, long look around before dialing 911, and you didn’t even attempt CPR. So, what really happened? She didn’t have anything worth stealing?”

Nora spread her arms wide. “Your detecting skills are off the chart, but before you take me downtown and book me, you might want to take a peek inside the house. After that, you can tell me what you’d steal if you were me.”

Hollowell was about to respond when the EMTs shuffled out the back door, carrying a body bag. They descended the stairs and gently eased Lucille Wynter onto the waiting gurney. Andrews trailed after them, holding his hat in his hands out of respect for the dead woman.

Spotting Nora and Hollowell, he approached the table.

He greeted Hollowell first. “Evening, Deputy.”

She flashed him a wide smile. “Evening, Jasper. I heard you were here, so I thought I’d stop by to lend a hand.”

“Well, I wouldn’t mind having some company when I notify Ms. Wynter’s next of kin. This kind of thing can be easier when there’s a lady present.” Andrews pointed at the garage. “Her son lives in an apartment in the back. His name’s Clem. You’ve probably seen him in the drunk tank. He spends the night with us at least once a month, usually after finding the bottom of a Wild Turkey bottle.”

Nora couldn’t believe what she was hearing. “Lucille has a son? And he lives on the property? How could she be living like that with him right here?”

“Living like what?” asked Hollowell.

Andrews jerked his head toward Wynter House. “Go see for yourself.”

Hollowell clearly didn’t want to leave Nora and Andrews alone, but curiosity won out, and she jogged up the stairs and into the boot room.

Andrews waited for several heartbeats before pulling an object wrapped in a plastic grocery bag from his uniform shirt pocket. “This was in the kitchen, next to the teakettle.”

Nora saw that an envelope bearing her name had been taped to the plastic bag.

“I didn’t open it. I assumed she owed you money,” Andrews said.

“Yes, but not much. She mostly paid in books, but sometimes she’d give me cash. Five or ten bucks.” Nora held the bag to her chest. “Andrews, this doesn’t make sense. She asked me for help, told me it was too late, and then tripped on the stairs? I mean, there’s no way she could’ve been talking to me after she fell, is there?”

“No. The phone’s broken. Probably happened during the fall.”

“Then why did she say it was too late?”

Andrews watched the EMTs load the gurney into the ambulance. “She was probably dizzy or confused when she was talking to you. She was old, Nora, and there’s hardly any light on those stairs. Look at her living conditions. There’s no way she was healthy.”

“Living in those conditions, I guess not.”

Andrews put a hand on Nora’s arm. “None of this is your fault. It’s a sad situation, and even though it’ll probably be ruled an accident, we’re going to do a complete investigation. I already took photos and we’ll be back here in the morning. I’ll make sure we know what happened to her, okay?”

The beeping of the reversing ambulance drew their attention to the driveway, and they both watched as the rig backed out onto the street and slowly drove away.

“I need to talk to Clem,” said Andrews. “You should go home.”

Just as Nora got to her feet, a man appeared from behind the garage. “Hey!” he shouted, lurching in their direction. “What the hell’s going on?”

Andrews held up his hands. “It’s okay, Clem. I was on my way to talk to you.”

The man came to a stop a good ten feet from where Andrews stood. He wore a Looney Tunes tank top, baggy athletic shorts, and Dollar Store flip-flops. His eyes were at half-mast, and he had the flushed face of an alcoholic. His pigeon-gray hair, which clung like a horseshoe to the lower half of his skull, stuck out in all directions. There were crumbs in his beard and his teeth and fingernails were nicotine stained.

Clem’s eyes slid from Andrews to Nora. “Who the hell are you?”

“This is Nora Pennington,” Andrews said. “She owns the bookstore. She and your mom met a few times a month.”

Clem’s expression sharpened. “Has she been giving you books to sell?”

Nora nodded. “A few.”

“How much do you get for them?” Clem demanded, slurring his words.

Sensing danger, Nora looked to Andrews for help.

“Listen, Clem. Your mom didn’t come to the door when Nora rang the bell, so Nora called her on the phone. Your mom answered and asked for help, so Nora went inside the house. She found your mom on the floor at the bottom of the stairs. It looks like she had a bad fall—a fatal fall. I’m sorry to tell you this, Clem, but your mom is gone.”

Clem dug the heels of his palms into his eyes. He took several deep breaths before lowering his hands and vigorously shaking his head. “Wait. Wait. I don’t understand. Are you saying my mama’s dead?”

“Yes. I’m sorry.”

Suddenly Clem’s hands were everywhere. They raked his hair, tugged his beard, and grabbed the neck of his shirt. They were birds let loose from a cage, frightened by their sudden freedom. He turned his back to Andrews, then swung around to face him again. His mouth worked, but no sound came out.

Andrews took a step toward him. “Hey, man. It’s going to be okay. Do you want to sit down?”

“No!” Clem held out his arms as if warding off an attack. “No! No! No!”

His eyes were wild, and his breath was coming so fast that he was practically panting. He rocked from side to side, like a cornered animal waiting to bolt.

Feeling her own anxiety rise, Nora darted a glance at Andrews.

Andrews stretched out a hand, palm up. “It’s going to be okay, Clem. But you’ve got to calm down. Can you focus on my face and take a slow breath?”

“Get outta here,” Clem murmured, his gaze shifting from Andrews to Nora. He threw his chin up toward the sky, filled his lungs, and screamed, “GO AWAY!”

Suddenly Hollowell was beside Andrews. “Who’s this guy?” she asked in a low voice.

“Samuel Clemens Wynter. He goes by Clem. I just told him about his mom, so he’s understandably upset.”

Nora wondered why Clem used his mother’s maiden name as a surname instead of his father’s, but didn’t think this was the time to ask.

“He’s also high as a kite.”

Andrews whispered, “We need to calm him down. Look at his face. His blood pressure must be through the roof. Why don’t you try?”

Hollowell nodded and took a step closer to Clem. She then put her hands on her heart and said, “Mr. Wynter? I’m Deputy Paula Hollowell, and I’m here to help you.”

Hollowell’s soft, musical tone surprised Nora. Every time she ran into the deputy at the station, the woman spoke to her in a cold, flat voice.

She must save the nice voice for the men she flirts with and the dogs she trains.

“Where’d you come from?” Clem cried. “Why are you all here? What do you want?”

He started backpedaling toward the garage, his hands flapping near his head. His muttering intensified. Sweat beaded his forehead and his skin was now the color of a ripe tomato.

Hollowell was about to pursue him, when Andrews told her to stand down. “Go on back inside now, Clem. You need to calm down. Go on. We’re not going to follow you.”

“Just leave me alone!” he shrieked before turning away. He lurched behind the garage and out of sight. A few seconds later, a door slammed.

“Can you radio dispatch? We’re going to need EMTs to give us a hand with Mr. Wynter.”

When Hollowell moved off a few paces to make the call, Andrews looked at Nora. “It’s time for you to go before this gets really wild.”

Nora glanced at the garage. “Will he be able to take care of Lucille’s arrangements? He doesn’t seem like he’s capable of taking care of himself.”

“It’ll work out. Go get some rest.”

Andrews was telling her as politely as possible to get lost, so she wished him luck and did as he asked.

* * *

Despite the heat, she drove home with the truck windows down. She wanted the air to whip her whiskey-colored hair around her face. She wanted the sounds of downtown to swirl around the interior cabin. Having just witnessed death, she wanted to be surrounded by life. She wanted it to stream in her window and curl around her.

As she sat at a red light on Main Street, she heard music and laughter coming from the outdoor dining area of the vegetarian restaurant. People milled in front of shop windows or strolled purposefully down the sidewalk toward the Pink Lady Grill or one of the higher-end eateries that required a reservation.

Summer was the height of the tourist season and even though it was the last weekend of August, Miracle Springs was still packed to the brim with people who’d come to bathe in the revitalizing waters of the hot springs, participate in sunrise yoga classes, and drink green smoothies. They’d come for therapeutic massage, meditation sessions, weight-loss programs, detox cleanses, couples counseling, terminal illness support groups, and women’s retreats.

Long before Europeans stepped foot on American soil, the Cherokee were reaping the benefits of the mineral waters that gave the town its name.

Eventually the tribe was driven out of the area. European settlers built roads and erected an inn at the crossroads. Travelers on their way to South Carolina, Tennessee, Virginia, or North Carolina’s Piedmont or coastal regions were encouraged to stop for a night of rest and a revitalizing dip in the hot springs.

Other businesses and homesteads followed the inn, and three centuries later, Miracle Springs was known across the globe as a center of healing.

Luckily, the town was located in a valley, which meant the suburban sprawl was limited. One could only build so much in a place surrounded by mountains. Vacation homes and timeshare condos now dotted the hills, but the powers that be held fast to tough restrictions and rules when it came to tree clearing and the preservation of green spaces. In a country where capitalism was king, this was a rare occurrence.

And while Miracle Springs didn’t have fast-food chains, lots of big-box stores, or dozens of cheap apartment complexes, most of its residents prospered. They weren’t wealthy, but they lived comfortably, and most were content with their lot.

People came from all over to experience the serenity of the little town, and Nora tried to soak up every ounce of that serenity before turning into the parking lot behind Miracle Books.

Like Nora, the building had lived a previous life. Before it became a bookstore, it had been a train station. And before her tiny house perched on the hill behind the shop became her home, it had been the caboose of a passenger train.

She climbed up the stairs to the deck and unlocked the front door. Dumping her purse on the sofa, she went straight into the kitchen to pour herself a glass of wine. She then sat at her little table, wineglass at the ready, and put the package from Lucille on the place mat.

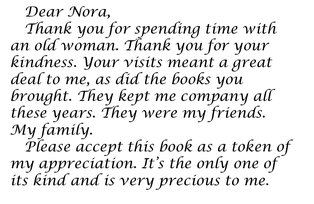

She opened the envelope first and pulled out a note written in gorgeous calligraphy.

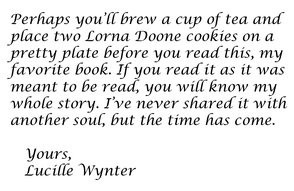

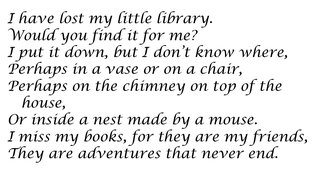

Bemused, Nora opened the plastic bag. Inside she found a thin book with a brown cloth cover. The book was roughly the size of her hand and had deckled edges. It smelled old and musty, like the pages were aching to return to the soil.

But the book had been precious to Lucille, which meant it was now precious to Nora.

She opened to the first page, which was blank. Though the paper bore the yellowed patina of time, it was of the highest quality. Nora could see the individual fibers running up and down and back and forth. And as she traced one of these lines with her fingertip, she heard a sound like wind whispering through dry leaves.

The next page was the title page. The words had been pressed deep into the paper. The ink was cave black and every letter with an ascender or loop, such as the  and

and  , had a dramatic swoosh. The rest of the letters were leaning slightly to the right as if too tipsy to stand up on their own:

, had a dramatic swoosh. The rest of the letters were leaning slightly to the right as if too tipsy to stand up on their own:

and

and  , had a dramatic swoosh. The rest of the letters were leaning slightly to the right as if too tipsy to stand up on their own:

, had a dramatic swoosh. The rest of the letters were leaning slightly to the right as if too tipsy to stand up on their own:

Below the title, in a much humbler font, was the author’s name:

Intrigued, Nora turned to the next page. This contained a woodblock engraving of a bookshelf stuffed with books and the lines:

Nora heard the jangle of keys on the other side of the front door and reluctantly closed the book. She wanted to see Grant. She wanted to feel his arms around her. But she also wanted to keep reading. She wanted to know exactly how one lost a library and, more important, how one found it again.

Glancing down at Lucille’s letter, she considered how much it sounded like a goodbye. But how could Lucille have known that she was about to die?

Unless she did.