Rage and Thaw

Pyrenees Mini-Break

Friday night. I have a completely free weekend ahead of me, perfect for frittering away in see-sawing emotions—rage-longing-rage-longing—and wasting time on social media, and finally going to see my family mostly just to remember I have one. I get an email from G, who I haven’t seen much for a long while, perhaps since the last time I was single, four years ago. I call her and she says that she’s going up to the Pyrenees that very evening. That she’ll spend the night there with a friend and his dog.

“Is it a date?” I ask her.

“No.”

G’s friends are very different to the ones in my circles, normally tied to the cultural sector.

“Pack a bag quickly, we’ll come pick you up.”

I don’t have any equipment, and am quite the city mouse, but I improvise a rucksack best I can. She brings me a sleeping bag and mat. G is impulsive, almost to the point of recklessness. She went by herself to the Himalayas. In many regards I would say that she is the person I know who is most my opposite. I say that because of her explosive power—as opposed to my British unflappability—combined with a certain, very punctual malice. G, however, is always willing to help others in difficult moments. I, on the other hand, am usually focused on my projects, and that leads people not to think of me as someone they can count on. In a family where the mother always works, the father’s not around, and there’s an autistic brother, it’s best to entertain yourself. G grew up with four siblings, and is used to working in a team. She is one of those people who show up for moving day and at hospitals, and usually have their doors open. That is highly prized in this era of people alone in front of their computers.

It doesn’t strike me as terrifically prudent, but that’s how G’s plans are, and I want to see snow and mountains. Snow is always snow, and it’s a way to maintain a link to Arcticantarctic, that place I’m trying to circumscribe with text and whose center I hope to someday conquer. On the way there, we are stuffed into a little car that smells of dog, along with the dog who’s whimpering the whole time. The friend, who is also named R—I’ll hear his name throughout the entire trip, as if he weren’t only with me in my thoughts but also present in the words spoken around me—says that he works hand-polishing metals for prestigious jewelry makers. Now that everything is done by machine or in China, it hadn’t occurred to me that such a job existed and was done in artisans’ workshops in our country. The idea of polishing jewels is interesting, I think.

“What do you do with the remaining scrap material?”

“We have to give it back. Polishing is a type of erosion. They keep strict control over the weight of the precious materials, milligram by milligram.”

I wonder if after all these years of study, work, and more or less failed relationships, I’ve been polishing myself or eroding myself. Is what’s left a gem, or a rock?

I’m at my lowest weight. I’m back in a state of economic instability and I’m single. Right now, having a family seems remote. I may be wasting on a psychoanalyst the decent salary I’ve had recently, which has allowed me to finally rent an apartment in my own name and have four nice dresses. The psychoanalyst supplants the big question, the solution, to use his vocabulary, metonymically. I’ve reached the phase where I’ve structured my identity around “lack,” but how can I change that? That question finds a perpetual answer in continuing therapy, in digging deeper. The only thing that gives me strength is writing: constructing meaning. Is it possible I get myself into all these problems just so I can later write about them? Did I believe in a dubious relationship to see where it would lead me, as a narrative? Perhaps my writing was calling me back, and I unconsciously detonated everything when I reached my limit? Writing is the poison and the antidote. Or as Lispector says, writing is a curse, but a curse that saves us.

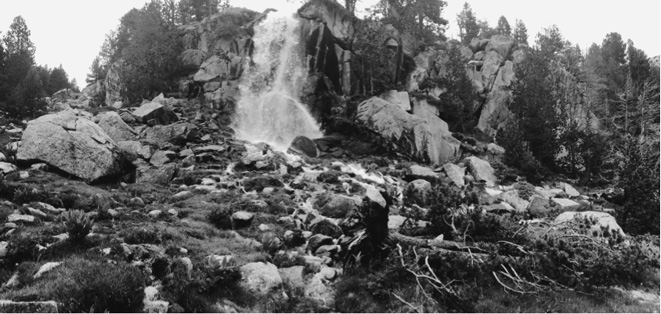

At midnight we arrive at Bellver de Cerdanya and spend the first night at G’s family’s flat. The next day we have a bumpy ten kilometers to the Perafita Refuge, 2,500 meters above sea level. There we find ourselves at the finish line of a fifty-kilometer race through the mountains. We watch as the exhausted athletes arrive after ten hours on their feet. Our plan is a stroll. In mid-June, the day is overcast and showery, and amid the rocky masses and fir trees you can see the melting snow in its full spectrum of states: calm, stagnant, violent, transparent, clouded. Streams, waterfalls, small marshes camouflaged in the fluorescent green grass. A mountaineer tells us that we can drink the water but never when it’s stagnant. I take note of his words, in many senses. Fuchsia flowers among the grass. We hear the bubbling of a nearby cascade. I wanted to cry anyway. I am a zombie Werther, wandering amid the firs after having fallen in love and shooting himself four times.

After an hour of ascent, we finally find the ultimate vestiges of the last snowfall of the season on the peak. That’s where the descent begins, now amid rocks and sand again. On the way down one of my knees starts to hurt. We only remember our dependence on the body when it’s not working. Luckily it’s nothing serious and we get past the most irregular stretches. At a certain height firs, grass and brooks reappear on every side. Wet feet. It starts to drizzle and it’s cold.

We occasionally pass some of the participants in the race, headed in the opposite direction. They have been walking for about eight hours. They stop for a moment to chat with us and we offer them dried fruit. There is a special solidarity in the mountains. Because we are all more aware of our fragility. Some of those passing in the opposite direction look like professional athletes. I exchange a glance with one of them who looks about my age; he has a black, quick gaze, beneath wavy damp brown hair stuck to his forehead. After a little while I turn and I see that he’s turned too. Later we come across some other participants between fifty and sixty years old. Soon we can make out the roof of the refuge at the base of the valley, among the fir trees. It is one of the race’s control points. There is a small group of people and a thin stream of smoke emerges from the small chimney. Before we reach the shelter we go through a terrain where the grass hides swampy patches. That rules out even the slightest possibility of keeping our feet dry. Lake, brooks, melted snow. Drizzle. Our dog leaps blissfully, takes the lead and lopes back to us, happy to be nowhere near asphalt.