The Civil Rights Movement 2:

‘Burn, burn, burn’

Whilst the ending of segregation was a huge achievement, the Southern states still managed, through intimidation and violence, to deny black people the vote and education. The civil rights movement had reinvigorated the Ku Klux Klan, especially in Mississippi, the poorest of the Southern states. During the summer of 1964, CORE targeted Mississippi in a campaign to increase the number of black people registered to vote, and to help run ‘freedom schools’. Attracting almost 1,000 volunteers, black and white, they were met with violence and intimidation culminating in the disappearance of three friends, two white youths and their black companion. When their bodies were found six weeks later in the Mississippi, their murders caused a national outrage.

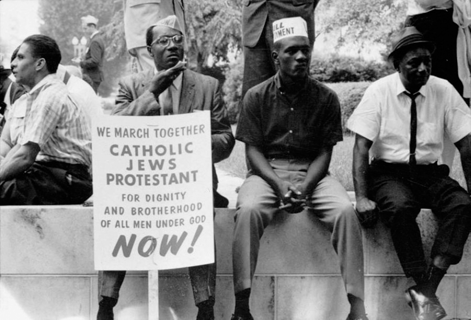

Protestors on the Selma to Montgomery march, March 1965

Photograph by Peter Pettus (Library of Congress)

On 7 March 1965, King, who had been awarded the Nobel Peace Prize the previous year, its youngest recipient at that point, led 600 demonstrators on an 80-kilometre march from the Alabama town of Selma to the state capital of Montgomery; its objective to highlight the issue of black voting. But Alabaman police, mounted on horseback and armed with clubs and tear gas, attacked the marchers. Televised across America, the nation had again reason to feel sickened by the actions of its fellow countrymen. President Johnson, describing it as ‘an American tragedy’, placed the Alabama National Guard under Federal control and ordered it to protect the demonstration. King led 2,500 people in a second much shorter march two days later.

The full march on to Montgomery recommenced on 21 March, and on reaching its destination five days later, and following King’s emotional speech, the demonstrators sang the civil rights anthem, ‘We Shall Overcome’, the words modified to ‘We Have Overcome’.

President Johnson and Martin Luther King at the ceremony for the signing of the Voting Rights Act, 1965

Photograph by Yoichi R. Okamoto

Five months later, Congress passed the Voting Rights Act. The unscrupulous practices that had prevented African-Americans from voting, such as literacy tests and poll taxes, were banned. In signing the bill, President Johnson invited King (pictured above, shaking hands with President Johnson) to witness the momentous occasion. Also present was Rosa Parks, a decade on from her famous boycott of the Montgomery bus service.

King’s non-confrontational movement had achieved much in terms of political and legislative equality, but what it had not achieved was economic equality. In employment, blacks were twice as likely to be unemployed than whites; black poverty as a percentage of the black population was far higher than white poverty. In housing, white neighbourhoods, fearing that black integration would adversely affect house prices, refused to sell to blacks.

In 1966, King led a march in Chicago against housing discrimination but the marchers were pelted with stones, and the protest saw the beginning of the white backlash. Although, in 1968, a law ending housing discrimination was introduced, it was hard to implement whilst estate agents, banks and home insurance companies refused to do business with black homebuyers.

In August 1965, in the Watts area of Los Angeles, an area populated by poor blacks, a white policeman drew his gun while arresting a young black man for driving offences. It triggered a six-day riot, that saw thirty-four die and thousands arrested. Whilst President Johnson launched his unconditional War on Poverty, summer riots became disturbingly familiar throughout northern cities during the mid-1960s as young, impoverished blacks rejected King’s non-confrontational approach and fought running battles with police. Johnson’s ‘Great Society’ had passed them by.

Economic dissatisfaction, frustration with the lack of progress in Johnson’s reforms, and the lack of hope certainly played its part, as did the total lack of black policemen. The police force was seen by the black population as the enemy; an instrument of the state.

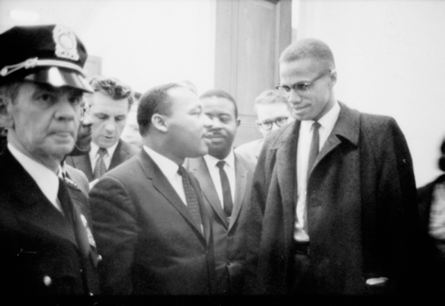

Black youths were beginning to reject King’s non-confrontational approach and were increasingly attracted by more radical leaders such as the charismatic Malcolm X. Born Malcolm Little, Malcolm spent time in prison where he converted to Islam, ditched his ‘slave name’ for ‘X’ and joined the Nation of Islam, a group founded by Elijah Muhammad, in which the black Muslims rejected Christianity as a white man’s religion and preached separation of the races. In 1964, Malcolm split from the black Muslims, reputably ousted for saying that the assassination of President Kennedy was a case of ‘chickens coming to roost’, and formed his own radical group, the Organization of Afro-American Unity, preaching black nationalism and advocating the use of violence, if necessary, to achieve it. Malcolm and Martin Luther King met but the once in March 1964 (pictured below).

Martin Luther King and Malcolm X, 8 March 1964

Photograph by Marion S. Trikosko

On 21 February 1965, Malcolm was assassinated by, it is presumed, one of Elijah Muhammad’s followers.