3. Tell me how it’s done

People don’t think in terms of information. They think in terms of narratives. But while people focus on the story itself, information comes along for the ride.

Jonah Berger, author and professor, Wharton School, Pennsylvania

Now that you understand why salespeople must tell stories and what a story is, let’s get into the details of how you can construct your own stories. Even the best storytellers benefit from structure and technique. When I asked Matt (the real estate CEO in chapter 1) to review the story I wrote about him for this book, he told me to add the point that it wasn’t until he understood the story structure from our training that he could help his team with their stories. As an aside, Matt was the best student in the training program.

There are three essential activities to finding and delivering a great story:

1. Interviewing and listening

2. Structuring

3. Practising.

When you master these three activities you’ll be able to deliver any type of story. If you miss these steps, your stories are likely to miss the mark. Rushing into storytelling before the stories are well developed risks wasting your future client’s time and missing out on the opportunities that a good story can bring.

We’ll look at each of the three story-building activities in turn.

Interviewing and listening

Interviewing is a key activity and skill for story creation. Every sales story type requires interviews in the preparation stage. Even your personal story, as you’ll discover in chapter 5. When you’re interviewing someone to learn their story you need to get them talking. When they talk about something interesting, keep them there to get more details. A special kind of listening is required. You need to listen in a curious but non-judgemental way, using encouraging body language, facial expressions and gestures. Ask confirming questions to ensure you have understood and use leading questions (‘Aha! Then what happened?’) to move them on to other aspects of their story.

Through such active, participatory listening, you show you are a good listener, and you’ll learn more too. If the other person is not using the language of story you’ve got two choices. You can either guess their meaning, filling in the blanks as best you can, and move on, or you can respond with confirming questions until you do understand. ‘Help me understand that — how did that work?’ ‘Could you give me an example of that?’ ‘How did you feel when that happened?’ You want their story but also to understand the emotions they experienced. Then you’ll appreciate and remember their story, because you lived it too. Active listening, tending the story, is an intellectual exercise and an act of empathy that requires your full attention. Empathy is defined as the ability to understand and share another’s feelings. That’s a critical skill if you need to tell another’s story and this style of interviewing is, by far, your best chance of being empathetic. That’s because you directly ask about their feelings. Many people think they can infer feelings from body language and voice tone. Lisa Feldman Barrett calls this the two-thousand year (wrong) assumption.

1 Be aware also, that the skill of empathy is value-free; psychopaths can be empathetic. As with all sales skills, intent is critical. Compassion is the appropriate value response from empathetic interviewing.

2In our story workshops we start by pairing up and getting each student to interview the other to draw out their career story. The interviewer then presents the story to the group. Knowing you’re going to be presenting someone’s story in front of the group, you pay attention. You take notes and mentally rehearse. When a teacher announces that 50 percent of test questions will be based on today’s lesson, the students listen with intent. The same level of attention is required when you interview someone to get their story.

Getting the essence of the story

A few years ago I was running a public storytelling workshop in Melbourne with a diverse group of managers, sales leaders and professional services people. When we split into pairs to do the personal story interviews, I moved from group to group, listening in to check that everyone was managing okay.

I had paired a business founder CEO with Mariam, a Somali refugee advocate. When I approached, the CEO was interviewing her and I overheard him asking Mariam about her life in Australia. Mariam told him she had written a book and the CEO wanted to know about how she was marketing and pricing the book and other aspects of her business life settling in a new country.

Later, when the group reassembled, the CEO told Mariam’s story. He told a good story about integrating into a new culture. He chose to start with her arrival in Australia as a refugee and the surprising fact that she was

housed by the government in one of Melbourne’s most expensive suburbs. But he missed important details that explain why Mariam is a refugee advocate. That story started in Africa.

I’d met Mariam for the first time a week before the workshop. Early in our conversation, when I complimented her on her English she told me that English is her fourth language. She’d left her native Somalia as a child to live in Kenya with her extended family because of the economic situation in Somalia. In Kenya she learned Swahili. As a girl, Mariam wasn’t allowed to go to school, but she used to sneak into her brother’s room to read his books. That’s how she learned English. She learned to speak Arabic fluently after getting married and moving to the Middle East with her husband to live.

On a trip back to Somalia, Mariam got caught up in the civil war fighting and was forced to flee to the Kenyan coast. She spent two nights on a ship with other refugees sailing down the East African coast without food or water. When she arrived in Mombasa, the authorities were prepared to let her into the country because she had a Kenyan passport, but they refused entry for her children. Mariam stayed in a refugee camp on a football field, and because she spoke Swahili she became the spokesperson for the refugees.

You can see a video of Mariam telling her story at master.mysevenstories.com/courses/sevenstories

This is an abbreviated version of Mariam’s story, but do you now appreciate why Mariam does what she does? We need to interview in a way that lets the full story emerge, and personal experiences may be more critical to the story than career and business events.

The mechanics of story structure

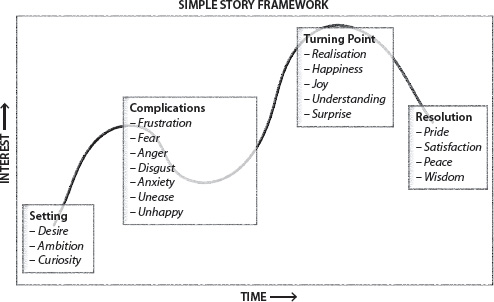

Recall from the previous chapter the simple story framework. Each circle in the framework is an event that must be described.

Figure 3.1: The circles represent story events that must be described.

The numbers indicate a good story preparation sequence.

Bosworth and Zoldan, in

What Great Salespeople Do3, recommend using coloured index cards for each event in the story — one colour for setting, one for complications, one for the turning point, one for the resolution and one for the business point. Start with the easy stuff — the setting and the business point. From there you can add the other parts of the story. The numbers in figure 3.1 indicate a good story preparation sequence. I’ve had great success with that technique in workshops. I’ve also had success with the single-page story template provided in appendix D. Participants’ stories are more natural when they are guided by a few bullet points on a card, provided they describe the full event and don’t just deliver it as bullets!

Most people find it easier to start by describing the beginning (setting) and the end (resolution). Then they fill in details about the complications and surprising events, and then they describe the turning point. Check that the story is making the intended business point. Finally, give the story a memorable name. That will help you recall it.

For stories that you experienced first-hand you may be able to finish here. When we tell stories that happened to us we naturally recall how we felt at the time, and the emotion comes out in our voice. For all other stories, we must think about the emotions that were experienced by the main character and check to see if those emotions are conveyed in our description and in any emotive words used. Great stories have emotional impact. We recognise them because we experience them viscerally. We predict how we will feel and our cortex sends the feeling via our internal body sense. That feeling in your stomach as you listen to a good story was made by your brain prediction.

In our business story workshops, we ask participants to tell a story about a time ‘when they helped’ as a preparatory exercise when constructing a business success story. Most students tell business stories, but occasionally a memorable personal one will emerge.

Teaching swimming story

Nick, a marketing manager, told about taking his three-year-old daughter to the beach to teach her to swim. Nick took her into waist-deep, murky water, took her floatie arm bands off and kept close by as she attempted to swim.

Nick felt something brush against his leg. His first thought was that it was his daughter, but he could see it couldn’t be her. He reached down into the water and pulled up a young, barely conscious boy from the sandy bottom.

Nick carried him, spluttering, ashore, whereupon the boy’s mother came running up and exclaimed, ‘Oh, there you are!’ She grabbed the boy by the hand and led him quickly away before Nick could explain what had happened.

You can see a video of Nick telling this story at master.mysevenstories.com/courses/sevenstories

I’ve retold this story in several workshops, and it never fails to draw gasps of emotion. But how is emotion evoked in this story? There are no emotional words, and neither Nick nor the mother’s emotions are described, yet the story drips with emotion. Because it has situational emotion. When we envisage ourselves in Nick’s situation we can imagine our emotions: ‘murky water…felt something brush against his leg…’ We’re in the water with Nick and we can’t predict what will happen. These words evoke emotions of foreboding and fear. Was it a shark? A box jellyfish? Seaweed? Then, ‘…led him quickly away before Nick could explain…’ You’re kidding me! The mother doesn’t even know her child nearly drowned! We’re exasperated, even outraged by this ending.

Nick’s story leaves us hanging. It doesn’t resolve neatly like a Hollywood movie, yet it is memorable and instructive.

The simple story framework of setting, complications, turning point and resolution has a sequence of emotions built into the structure, as shown in figure 3.2. This sequence is part of the story framework, an emotional progression that we learn and that may vary from culture to culture. Reviewing the emotions listed in figure 3.2, think about the language you could use to describe each of the four events in the structure. If the hero of the story has a strong desire for change, how do you describe that in the setting? Similarly, determine the primary emotion in other events and look for words and phrases that convey that emotion.

The most interesting stories have emotional contrast. We’re taken on a journey through different emotions as well as events.

Figure 3.2: The emotional arc of the simple story framework

Figure 3.2 shows typical emotions that may be experienced at each stage of the story. You may not need to state that your character was feeling frustrated (for example) during the complications stage, because your description of what happened could suggest any emotional responses implicitly, just as in Nick’s swimming story.

How long should stories be?

Your business stories should be as short as they can be while still making your business point. It’s said that American author Ernest Hemingway once won a ten-dollar bet by writing a story in just six words. The story was:

‘For sale, baby shoes, never worn.’

This story’s origins remain unconfirmed, but there are some things I’d like to observe. First, it doesn’t follow my framework! We, the readers, have to do all the work here, creating multiple story possibilities in our minds. I teach a story framework because we are not Ernest Hemingway! A genius is someone who can break out of the framework and still connect powerfully with the rest of us.

Another kind of genius is the stand-up comedian who can stretch a story out and keep an audience in stitches for an hour. In this book we won’t be concerning ourselves with stories at either of these extremes. We’re going to be telling everyday stories. Our shortest story is just 80 words long and takes twenty seconds to tell; the longest is 1000 words and takes five minutes. I can’t get the five-minute story any shorter, but it is one of my favourites. It’s the last story in this book. But for our purposes, a couple of minutes is a good mean to aim for, as it will fit easily into most business meetings.

A common comment in our story workshops is that ‘some people don’t like stories’ and even a 20-second story would be too long for them. I used to believe that. I used to think it’s better to avoid telling stories to driver-style CEOs or numbers-focused CFOs. Now I know those people also appreciate stories. Their brains are like everyone else’s, but their time is precious, so your story must be tight and must make a relevant business point. The surprising truth about good stories is they work for everyone and they mostly do their work unnoticed.

The surprising truth about good stories is they work for everyone and they mostly do their work unnoticed.

When you have structured your story arc and worked on the description of these events to fit the emotional arc, it’s time to practise and refine the story. There is no substitute for practice. I’ve found one of the best ways to practise is to record your story using a video messaging app like WhatsApp

4 and then listen to your delivery. Record and re-record until you’re happy with it, then send it to a friend for feedback. Every repetition will make the story shorter, tighter and more interesting.

Stories are too important to fluff in front of your potential client, so practice is essential. In Putting Stories to Work, Shawn Callahan warns against writing out stories in full because we don’t talk the way we write. That’s good advice. Most of my clients practise with video message then upload the video to their corporate story library.

Another way to get started telling business stories is to join a public story workshop. That’s not a plug for our workshops — we don’t run many so you probably can’t get into one of those. Search Eventbrite or a similar event website and you will find reputable companies offering story skill development. It doesn’t really matter if the workshop you join focuses on leadership, change management, sales or some other business area. You could also join Toast-masters or a Rostrum club. The key is to experience co-creation of stories in a facilitated group.

One thing to look out for as you practise is voice tonality. It can make a huge difference to the power of your stories.

It’s not just what you say…

Recently I was facilitating a company creation story session with one of the sales teams I work with. I’d researched and written up their company story. When we practised the story in a group, I gave each of them the option of paraphrasing the story in their own words or reading my story. The ones who chose to read the story delivered it in a flat monotone. When I read it, it was animated by inflexion, pacing and the nuances of voice tone. The company’s marketing manager said my version sounded like a completely different story.

Of course, I’d had the benefit of practising the story as I wrote it, but the reality is that written stories never sound natural when we read them, because we don’t write the way we speak. If you record yourself telling the story, listen for your voice tone. Think about rising and falling inflexions, pauses and changes of volume.

Voice tone in storytelling

Voice tone in business communication, like storytelling, is an entire subject in itself. And like storytelling it is poorly understood because it operates at an unseen level, influencing conversation outcomes. In our Persuasive Voice Tone

5 training courses we teach salespeople how to employ the five ‘selling’ voice tones the best salespeople use, and how to avoid the five non-selling voice tones. As a memory aid, we equate each voice tone with an ‘archetype’ character.

The selling archetypes are:

• The Authority — a sharp, confident voice tone

• The Friend — a warm, easy, melodious voice tone

• The Custodian — a low-pitched, furtive, secretive tone

• The Investigator — a curious, questioning tone, used in exploratory conversation

• The Negotiator — a reasoning, persuasive tone, used when negotiating.

Only two of these tonalities — the Friend and the Custodian — are most suitable in storytelling contexts.

You can tap into the Friend tone by smiling and imagining the customer is your best friend. You’ll naturally slow down and become more relaxed and outgoing.

To assume the persona of the Custodian you first raise your voice (loud), then lower it (soft) when you start relating the story.

‘Psst! Wanna hear a secret?’

‘You know…I never really wanted to be a salesperson…’

‘That’s interesting… Just the other day I was talking with a client just like you, and…’

When you adopt a hushed tone, your audience leans in — they want to know the secret in your story.

What type of story to tell and when to tell it?

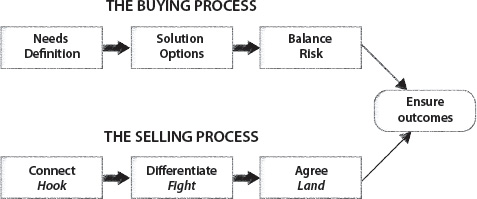

The seven key stories discussed in the next three parts work best at specific places in the buying and selling process (see figure 3.3). There are three steps to the buying process. First is the awareness of a need for change, then potential solutions are evaluated to see if the need can be satisfied, and finally a decision must be made on whether or not to take action.

Figure 3.3: The buying and selling processes

In the selling process there are four steps:

1. Prepare and collect stories. Before you attempt to connect with prospective clients you have to know what you are selling, exactly what your buyer values and who your buyer type is. Without that information you have no story to engage your potential client. The seven stories prepare you for the challenge ahead.

2. The Hook. This is when you win the right to start the process. It means connecting in a way that gains your future client’s trust, both in you as an authority and in the prospect of working with you. The best salespeople connect before their future clients even realise they have a need.

3. The Fight. In this phase you must persuade your future client that your solution, your company and you personally can and will satisfy their need and achieve the outcome they want. There will always be competing ideas in the buying organisation. The most powerful motivation will be to do nothing! Change necessarily involves risk, and since most people and companies are risk averse they are hard to change. The larger the organisation, the more entrenched the status quo. So you need to fight for your future client’s mind space, and you’ll need to be persuasive. Your fight stories will help your buyer to appreciate your unique offering.

4. The Land. In the final phase you’ll land the deal. This means gaining internal agreement by overcoming typical barriers around risk, prioritisation and budget. Landing is the most challenging phase of the selling process, particularly for large deals worth millions. The larger the deal, the more decision makers are involved, and the greater the complexity for both your future client and your own company. It’s also less likely that you’ll be able to interact with them all personally, so you’re going to need to rely on your champions within the buying organisation. The landing stage of large deals is where the best salespeople shine, often using remote persuasion on people they don’t even meet. If you want to be able to land large deals, storytelling is the crucial skill because it arms your sponsor with the story tools to get the decision made.

When you consistently deliver on these four phases you’re doing your job and you’ll excel as a salesperson.

Story planning and the story library

I grew up in Tasmania and was introduced to bushwalking by my father at a young age. By 15, I would set off with like-minded school friends on days-long bushwalking expeditions in the remote national parks of central and south-west Tasmania. One of our favourite diversions on these trips was joke competitions. Around a campfire or lying in the tent, we’d spend hours swapping jokes. The rules were simple: each took his turn and each joke had to be inspired by an aspect of the previous joke. The winner was either the last one standing or the one who cracked us up so badly we couldn’t go on. The gorilla-and-the-salami-sausage joke comes vividly to mind.

I’m not saying you need to be good at jokes to tell good stories, but there are common elements. Good jokes rely on weird analogies. They’re told, refined and retold — bad jokes becoming less so…The best jokes are stories, sequences of events with a surprising, humorous twist. Often something in the preceding conversation triggers the story. Of course, the objective of business storytelling is to make a business point rather than to get a laugh, although sometimes you can have both.

It’s okay to recall a joke when it’s triggered by another joke, but hoping a good story will come to mind at the right time during a multi-million-dollar sale is a big risk to take. Better to think ahead about the story you’d like to tell. Many sales teams use a call planning process. This is a worksheet for salespeople to capture their meeting objectives and the topics they want to discuss in an upcoming client meeting. It’s a discipline I tried to implement without much success when I was a sales manager, one of those good process ideas that peter out because the sales team resist it. A simple form of call planning that requires no process or ceremony is to ask two questions. First, the pre-call question, the one I ask my salespeople: ‘What story will you tell in this meeting?’ Then, in the post-call briefing: ‘Did you tell your story?’ You’ll know if they did, because you’ll get an excited description of how the story was received.

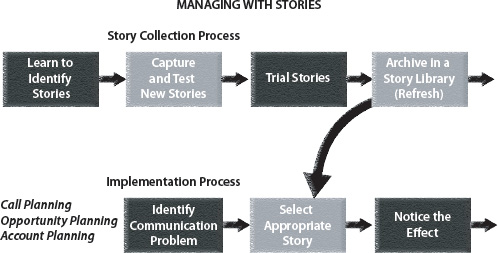

Figure 3.4: The sales leader’s story management process

The best way to prepare is to create and preserve your stories in a ‘story library’, a searchable story archive that’s accessible to everyone in the company. With this resource, you no longer need to rely on the conversation to trigger a story. What’s more, the entire sales team has access to all the good stories. It’s my experience that in any company only a few people have good sales stories to draw on. By building up a story library, you multiply the success of your best salespeople.

In figure 3.4, along the top row you see the process of creating your sales team story library. The bottom row shows how to incorporate stories from the library in call, opportunity and account planning meetings with your team.

You can see what our story library looks like by visiting

stories.gifocus.com.au. Most of our stories are written, but the fastest way to collect stories is to video them using a smartphone. No need for editing or a fancy recording setup, just make sure you have reasonable sound quality.

Story preparation checklist

Start collecting stories.

It’s a business story

only if there’s a

sequence of events happening to a

character that are

unpredictable and make a

business point.

Practise with video and share your stories in a library.

Start collecting stories.

Start collecting stories. It’s a business story only if there’s a sequence of events happening to a character that are unpredictable and make a business point.

It’s a business story only if there’s a sequence of events happening to a character that are unpredictable and make a business point. Practise with video and share your stories in a library.

Practise with video and share your stories in a library.