5. What makes a connection?

It’s like everyone tells a story about themselves inside their own head. Always. All the time. That story makes you what you are. We build ourselves out of that story.

For most of our history humans lived in small groups, bands of 50 to 150 people. Encountering strangers was potentially dangerous — they might try to kill us. Over evolutionary time we developed social responses and behaviours to address this danger.

In

The World until Yesterday, Anthropologist and bestselling author Jared Diamond talks about the cultures of hunter-gatherer and agricultural tribes that made contact with the modern world only in the 20th century. He describes what happened in the Papua New Guinea highlands when two strangers met on a jungle path.

1 They would sit down and start asking about each other’s relatives. ‘Who do you know?’ They would try to find a way to make a connection to their own tribal group and family. Without any common connections, the situation was dangerous and likely to end in fighting until someone was killed.

Of course, we’ve moved past killing strangers, yet we are still trying to determine whether any given engagement is safe or whether we should break it off. Today when we meet strangers, our minds are still attuned to that ancient behaviour, trying to see how we are connected and whether our contact is safe. We exchange stories about ourselves to find common ground. Part of our story is our tribe, or our company.

A prerequisite for being a friend is that you’ve exchanged stories in a common context. If you think about people who are your friends, you know their story and they know yours. To connect with a stranger (such as a new client) you need to tell a connection story. But that is only half of it. We tell our story so strangers will share theirs. The tricky part is to persuade your future customer to share their story.

You have to tell first, and here’s why. They are unlikely to tell you their story unprompted, as typically strangers don’t just start sharing their stories. If they do, their story is unlikely to be structured in a way that will lead to a ‘fast friendship’. The content of connection stories is important. You must ‘seed’ the stranger’s story with the content of your story, which is why you need to tell your story first.

You may have read admonitions from sales pundits against ‘telling’ in sales. As the mantras go, ‘Selling is not telling!’ and ‘Question first. Listen then tell.’ But those warnings are about a different type of telling. They are about starting a conversation by talking about your products and services. But with storytelling, if you tell your own story first and then prompt your future customer for theirs, you’ll ensure a crucial exchange.

Your personal story must answer the unspoken questions the stranger has about you. Why do you do what you do? Why are you here in front of me? Are you safe? Can I trust you? Are you an authority? Can I respect you? Your objective is to answer those questions in a one- to three-minute story, then close with something like, ‘What about you? Why do you do what you do?’ By convention, the stranger will respond with a story of similar scope to yours. If you shared something personal, say about your children or your life partner, then you’re likely to get something personal back, which is a fabulous thing! Exchanging personal details about the important people in your life is a great way to make friends quickly.

You’ll read a version of my personal story in the next section. I include details about my partner, Megan, being eight months pregnant when we moved country for my first sales role. I also explain how lucky I was in my first year selling. You may not be comfortable sharing private details in a first meeting, but I’m going to coach you to share the true reason why you do what you do. That’s what the stranger needs to hear; indeed, it’s what you both need to hear to connect and build a business relationship. The best way to answer the buyer’s safety questions is to do so in the context of a compelling story, because then you control the interaction.

The story you tell first should contain within it the reason you can be trusted, your honesty, your authority and your relevant experience. In response, you receive their story, which puts you in a privileged position. Once you’ve exchanged stories, you’re on the way to being friends. You’re on the fast track to building trust and rapport.

Telling personal stories is not well understood in sales. The main objective is not just to tell a personal connection story; it’s to exchange personal stories and cease being strangers. It’s the exchange that brings two people together to know and trust each other.

It’s the story exchange that brings two people together to know and trust each other.

Once you have shared personal stories, you move on to sharing your tribe’s or company’s story along with key staff ‘warrior’ stories. The goal with each of these connection stories is to move further into the ‘friend’ category. To do that you need to exchange stories on three levels:

• You. Who are you and why do you do what you do (your personal story)?

• Your tribe. Who is your company? What is their purpose and how do they succeed (your company story)?

• Your warriors. Who are the champions in your company and how will they help this stranger (your key staff stories)?

Together these are your hook stories.

Many salespeople, especially in western cultures, have the mistaken idea that ‘meeting time’ is precious and they need to get straight to the point by talking about their products and services. There are several problems with this approach. The first and most fundamental is that until you connect, any information you deliver will not be trusted. You’re unlikely to be persuasive because you’ve missed the first critical step. First you need to connect and make ‘friends’, then what you say will be listened to and accepted. Of course, the stranger may listen politely even if you haven’t shared stories, but their guard will be up.

I’ll have more to say later about time perceptions in business meetings. For now I’ll just say it’s never wasting time to make a good connection with your future client.

Connection stories are stories about you, your people and your company. They communicate how you got where you are and why you do what you do. It’s important to have a narrative thread running through your stories, with one event flowing naturally to the next. They must also be realistic, conveying the obstacles and vulnerabilities of the journey. And they must be true stories. A story that shows a steady linear progression to fabulous success is not believable, interesting or relatable. You need to include things that went wrong and personal stumbles so the ‘stranger’ can relate at a human level. By all means end the story on a positive note, but the ups and downs of your journey are what give your future customer the confidence to tell their own story.

As a salesperson, your first hook story is your own personal story, but your key staff stories are critical too, and in a way they are easier to tell. Your personal story needs to be humble and self-effacing, or at least you need to avoid bragging about your experience and performance. But when you tell the story of an important player in your team, you can afford to be complimentary and to build them up.

The third type of hook story is your company creation story. Here you are representing the organisation rather than yourself. Your future customer will want to know who this company is, what they do and what they can offer. If the company is well known, is their idea of it favourable or even accurate?

You need to convey why what your company does is important and relevant. The time-honoured way of doing this is to list your company’s achievements. ‘We’ve been in business since…We have a staff of…We’re number one at…and we’re great at…’ This type of approach does not connect. Worse, it invites pushback and rejection. You’re hitting them with information they’re likely to refute because it is presented as assertion and opinion. It’s in the wrong format. You need to communicate your company’s credentials in the format your client is most open to: you need to tell your company creation story.

Many of the business owners and sales leaders I work with are natural storytellers. Their stories spill out spontaneously, stream of consciousness style, one after another, like the joker holding the floor in the pub. These stories have an impact, but they’re even more powerful when delivered strategically, consciously and succinctly. We’ll learn how in the next chapter.

We’ve discovered that a few short, high-quality stories are much more effective than a great cascade of stories, and that they’re also much easier to teach a sales team.

Mike Bosworth is famous in B2B sales training circles through his influential 1995 book, Solution Selling, which is essentially a questioning skills manual. Solution selling became the reference training method for many corporations, including Nokia when I was working for them in the late 2000s. We trained all our salespeople in Bosworth’s method, which specified the type and sequence of questions to ask in a sales conversation. There were nine boxes of question types and you had to know where you were within the boxes during the customer conversation.

I was a big fan of Solution Selling long before I joined Nokia, but I struggled to teach my people his questioning technique because it’s complicated. It’s one of those techniques you’re likely to get worse at before you get better, because you are forever trying to think of the next question type rather than listening to your customer’s responses. Solution Selling is also silent on the rapport-building and the persuasive power of storytelling

In 2012, Bosworth addressed the rapport issue by teaming with Ben Zoldan to write What Great Salespeople Do, a wonderful book on storytelling. Curiously, the book argues against the solutions selling approach and instead teaches storytelling as a sales conversation methodology. Central in the book is a story Ben tells of when he worked with Bosworth as a solutions selling sales trainer, which I’ll paraphrase here.

The sales trainer’s nightmare

At the end of a training course for a corporation, a student invited Ben to observe him in a client meeting that was due to start in the same building. (This situation would have filled someone like me, who has been a sales manager and sales trainer, with deep foreboding.) Ben accepted. When they stepped into the meeting room they were surprised to find the student’s CEO chatting with the visiting client team. Oh well, Ben thought, this is an opportunity for the CEO to see the results of the training program we’ve been delivering.

The student duly launched into a series of questions following the questioning framework he’d been taught by Ben. The lead client leant back, arms folded and refused to play along. While the client became more and more frustrated with the line of questioning, the student persisted. Concerned about this poor reflection on his training method, Ben jumped in to retrieve the situation, but his questions made the client even more unresponsive.

Finally the CEO of the student’s company leant forward and said, ‘You know, this reminds me of when I was working at…’ and proceeded to tell a story about a situation similar to the visiting company’s. As soon as that story was finished, the client leader related a similar experience. Then they were trading stories about their families…and the meeting got back on track.

From this and similar experiences, Bosworth and Zoldan were persuaded that the solutions selling method didn’t work, and they discarded it in favour of a storytelling approach. My own view is that questioning techniques are not invalidated by experiences like Ben’s. He and his student simply got the sequence wrong. The exchange of stories has to come first. After that transaction you can relax and safely adopt a questioning technique — and tell some more stories. Questioning before trust is established doesn’t work.

The modern B2B sales process is said to have been invented by John Henry Patterson in 1893

2, when he was working for National Cash Register (now NCR). Patterson codified the first professional B2B sales process, known as

The Primer, by inscribing it in a twelve-page notebook his brother had given him. The Primer covered every aspect of the sales conversation ‘performance’. NCR salespeople were taught to establish rapport ‘as the Primer advised, by studying the prospect and gaining his confidence’.

3 First they would notice some particular in the person’s office or appearance, maybe a photograph or ornament on their desk or a painting on the wall. Then they would ask about that and pretend to be fascinated by the person’s response. The method probably enjoyed some success, but it was essentially manipulative and it’s now seen for what it was — fake and inauthentic.

Today this sort of warm-up is not received well in most business settings. People are too busy and you’re not answering the fundamental unspoken questions: Who are you? Why are you here? What’s your intent? And why should I trust you? If you’re not addressing those questions, if you’re talking about football or golf or some other unconnected topic, it’s likely to be viewed as time wasting.

Where I live in Melbourne, Australia, many companies think hiring a former Australian Rules footballer is a good idea for sales roles. A well-known sporting person can easily start a conversation with people who know football, but their experience is based on sporting ability that more than likely has no bearing on the client’s business, so how can they help? The idea that the ability to share a conversation on any subject is the key to rapport is wrong, because such discussions don’t address the buyer’s primary safety concerns about your trustworthiness. From the seller’s perspective, this approach is also less likely to lead to a story exchange that will form the basis for a ‘friendship’. Of course, ex-footballers can be great salespeople — I know many who are — but making a connection only on the strength of hero worship is not sufficient.

Why do people still follow a traditional approach?

That first business meeting with someone you don’t know can be an awkward experience. You asked for the meeting and it’s your job to start the conversation. It doesn’t feel right (and it isn’t right) to jump straight to business, but what else can you talk about? Just as when meeting someone for the first time at a party, you look for things you have in common.

It’s often said that good salespeople are easy conversationalists, that they have the ‘gift of the gab’. But most business people are impatient. They don’t want to waste time on small talk; they want to know what you’re going to do for them. Now.

Salespeople have learned to drop the conversation about the family photo on their customer’s desk, but if they jump straight to business they’ve missed a crucial step. A common misconception is that if you tell a story about yourself, you’re time wasting again. That’s not true. The most interesting things in the room are not the furnishings or the latest sports news. They are the two humans who don’t yet know each other. Let’s talk about that.

Personal stories get attention. We are naturally drawn to stories, but especially personal ones, because they’re unpredictable and we want to learn from them. Could our life have been like this person’s? How did they survive and succeed? Chatting about last Saturday’s game may be entertaining — although there’s a good chance that at least one party is only feigning interest — but football chat doesn’t progress your business relationship. When you tell a relevant story that has an unpredictable sequence of events and human interest, people take notice. They listen, and they don’t even notice time passing.

What’s in a personal story?

That’s a good question. No one has time for your whole life history. Personal stories are vignettes, snapshots of times in your career that illustrate who you are and why you do what you do. When I tell my story as a sales trainer and business consultant, I need to explain how I got into sales, why I want to help sales teams and how I can help. I graduated from university as an engineer. At that time I had no interest in sales. In fact, I saw sales as a dark, manipulative art. So here’s my short story.

Mike’s story

In 1996 I was working in the United Kingdom as a rock physicist. I would analyse data from oil and gas wells and interpret the rock and fluid type. My company had created new software for geoscientists and wanted to sell it to oil and gas companies. One day I was called into my manager’s office and told, ‘Mike, there’s this opportunity for you that’s going to be great for your career. We want to send you to Norway to sell our software.’

‘Whoa! Norway, excellent!…Sell software? I don’t think so…that’s not me.’ It was a dilemma. At the time Megan was eight months pregnant so moving country should have been out of the question, but she’s more adventurous than I am! We ended up flying on the last possible day the airline would accept her. We landed in Stavanger heavily pregnant and with a two-year-old toddler. When Megan was giving birth a month later, I was busy on a very early model mobile phone, trying to be a salesperson.

I received good sales training, but I didn’t have much idea of what I was doing. In that first year, though, I closed the biggest deal in our company division, and it happened purely by accident! I was, as I now appreciate, in exactly the right place at the right time. The deal was done because of a remarkable ‘mobiliser’ in the client organisation. However, as often happens with salespeople, I took that good fortune as evidence of my own talent. I thought I was good at sales. I stayed selling and ended up in sales leadership, managing sales teams in Russia and throughout Europe. In a booming market, I had considerable success.

When it was time to come home, we decided to live in Melbourne, where there was no possibility of work in the oil and gas industry. I worried I might not be able to find work. Do you know the feeling? Lying awake, bathed in sweat, worrying about never finding work again. As it turned out, I told a good story in a job interview and managed to get a role in the telecoms industry selling mobile networks to telecommunication carriers. I used to joke that I was perfect for the role, apart from the minor impediments of zero knowledge about my products and services, my industry or my customer. When I learned the trick of changing industries, I story-told my way through four more industry transitions, always in sales roles.

Throughout that time, as a sales leader but still an engineer at heart, I wanted to understand how we sell. What’s the best technique? Who are the best salespeople? What makes them good? I had a common experience across diverse industries: I had sat next to salespeople in client meetings as they routinely said the wrong thing, failing to connect, to differentiate, to close.

I noticed that the best salespeople told stories that made me think, and I came to understand that this was the answer. It has consistently worked for me, which is why I’ve found success in several industries, and I believe it’s what most salespeople need to learn. In 2014 I decided to go out on my own as a consultant, to see if I could make a difference for sales teams by teaching them storytelling.

That’s an example of a personal story. It’s quite long, and I wouldn’t always tell it with so much detail. I might tell different parts of the story depending on the context. There are three turning points in my story: my conversion from engineer to salesperson; my return, jobless, to Melbourne; and my decision to become a business consultant.

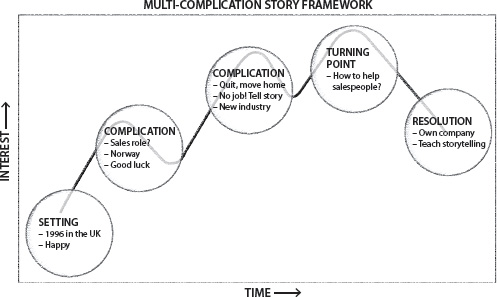

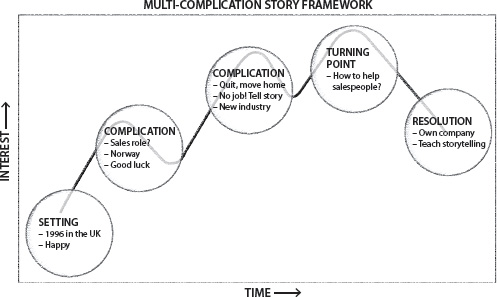

You can visualise the story as the simple framework with two complication cycles, as shown in figure 5.1. Each complication event is a mini-story in itself and could be told independently.

You can select from a pallet of personal story ‘vignettes’. Choose one or two career events that have a story trajectory and that answer the question of why you do what you do and why you’re sitting here, in front of this stranger.

To develop your personal story, I recommend you have someone interview you. I’ve found most people are not good at identifying what’s interesting in their own story. They know the story so well that to them it’s just not that interesting. (Interviewing skills are also really useful for eliciting key staff stories, as we’ll discuss in the next chapter.)

Other people will find different things about you interesting. How did you get into your field? What did you study at university? What made you want to do that? What happened to make that happen? These are the sorts of questions the other person will have in mind. They won’t ask you, but they will be curious, and you can answer at least some of them in your story. If you choose to seed your story with personal references, like my mentioning that my partner was pregnant when we moved to Norway, then you are likely to trigger personal disclosures in your client’s story.

You may prefer not to share personal aspects of your story. Be aware, though, that a personal connection is stronger than a business-only connection. When I talk of my experience of being with salespeople when they’re saying the wrong thing, and my conviction that there has to be a better way to connect, and to do so more successfully, I’m conveying my intent and my purpose. That’s why I do what I do.

Figure 5.1: The story framework for Mike’s personal story

Why is connecting a hook?

You may be thinking ‘hook’ sounds a bit aggressive and manipulative. Why do I call them hook stories? As we’ve discussed, the fishing analogy works on several levels. You have products and services and an assumed market for them. You need to find a way to get in front of people who can use those products and services. Your story is the lure and if you hook properly and make a good connection, the rest of the sales process will be much easier. Yes, there may be struggles along the way, but you’ve got a good chance of going the full distance.

Without a secure connection, you’ll get some false bites but the fish will always break free. When you hook properly, you’ve started a process that can lead to new business. You won’t land them all. Sometimes the fish will jump off the hook; sometimes your line will break because your position isn’t strong enough, but with a proper hook you give yourself a chance — you’re in the game. You cast your connection stories near the fish. In the exchange of stories your client decides whether or not to bite. If they trust your intent and believe you have sufficient authority to help them, they may allow themselves to be hooked.

I know the analogy breaks down when you consider it from a real fish’s point of view. After all, a fish generally doesn’t get a good deal when you catch it, but in a business deal both sides must benefit. When it comes to landing the deal, it must be cause for celebration by both buyer and seller.

To stretch the analogy, marketing is like setting a fishing net, going away and hoping you’ll make a good haul when you pull it in later. Selling is more one-on-one intentional. I aim to catch a particular fish. Based on my own research, I’m convinced our business relationship will create mutual benefit, so I cast my line. The salesperson who comes back from a meeting excited by the prospect of a deal may have got a bite but didn’t hook their fish. It’s important to understand that to be successful, you need a connection that hooks deep.

That my sales career has spanned multiple industries is unusual. It means I have great connections around the world in diverse industries, and many of them are still friends. If I travel to a place where I’ve done business in the past, I like to catch up with past clients even though I no longer work in their industry. The story exchange creates lifelong friendship.

In the next chapter, I’m going to show you all that goes into a connection story, and how to develop your own diverse connection stories so you have a range to choose from, which is where the creative part comes in.