11. Your buyer on remote control

When your values are clear to you, making decisions is easy.

Roy Disney, Disney Corporation

You tell values stories to reduce your customer’s fear of perceived risks. You tell sales teaching stories to help your future customer reach consensus in the decision committee in favour of your solution. The values story is the answer to the question, what happens if things go wrong after we decide? The teaching story is the answer to the problem of failing to decide, overcoming the ‘do nothing’ decision or the wrong decision. The values story provides comfort in the face of risk; the teaching story inspires action.

Let’s look at each of the two Land stage story types in turn to understand exactly what they are.

Values stories and risk avoidance

Few significant purchases are made by a single person. Personally, Megan and I don’t spend more than a couple of hundred dollars without consulting each other. Our family is a two-person decision team in all of our household expenditure decisions. For large B2B sales purchases you can count on many more decision makers. We involve other people in the decision process because we want to avert the risk of failure: it’s a risk avoidance strategy and standard policy for most companies.

There are statistics about the average number of decision makers involved in a B2B sale. CEB reported an average of 5.4 decision makers in a 2014 study of more than 5000 stakeholders.

1 I don’t know the relevance of those statistics for your business, but the rise of consensus-based decision making is real. In my experience there are between five and ten influencers, and sometimes more. Not all of those people are significant contributors to the decision, but they can veto it or throw obstacles in the path of a decision in your favour. You’ve used insight and success stories to locate and influence your sponsor, the person who wants your solution. But you also need to influence others on the decision committee. You may not be able to meet with them, but they are almost always concerned about risk. Your values stories will show these people that your company will overcome any problems that may potentially occur, or that those problems will never occur because of your company values.

Let’s review some questions a buying committee might have before spending a few million dollars. Their first concern will be whether the decision will have a financial return. ‘Will the supply company deliver what they say they’ll deliver? Will we get the outcome we expect? What if there are problems and it doesn’t go quite as planned? Will the supplier stand by us? What if there’s a catastrophic failure? Will they still support us? What if there’s a technical problem and the new system goes out of action for several days? Will they behave ethically in those situations? If we pay upfront, will we definitely still receive what we think we’re purchasing? How can we be sure? If those things go wrong, then what? What would happen to our company? Could we continue to operate? Continue to trade? Will I lose my job? Will my team members lose their jobs?

People can build a mountain of negative hypotheticals about what could happen and expand those stories into deal-killing fantasies, if you’re not careful. So what would really allay those fears?

One answer to a perceived risk is a success story, though you may not have other clients who have successfully navigated the particular risks of concern here. But a values story — a story about how your company behaves when things go wrong, for example — can be extremely powerful. It might seem counterintuitive to talk about things going wrong at this stage of a deal. In fact, your future client wants to hear this story. They’re not convinced by the story that says everything will be perfect. That’s not believable.

Several of my values story examples date from my time selling for the German multinational conglomerate Siemens. A core value of Siemens is ‘reliable engineering that we stand behind’. I was struck by the number of stories on the theme of ‘We stick with you until you get your outcome’. When I worked at Siemens in the mid 2000s it was still a company dominated by engineering, with hardly any ‘sales culture’, not an American-style marketing and sales–led company at all. But beneath the pragmatic, reserved engineering image were hundreds of values stories that influenced both clients and employees.

The train radio story

In May 2004 I experienced those values first-hand. I was working in Sydney on temporary transfer to help with the project management of a large tender. We had a team of fifty experts flown in from all parts of the world to assist, and the bid budget was $1.5 million. That large.

One Monday morning our state manager, John, arrived at work looking as if he hadn’t slept. The previous day the radio network our company supplied to the metropolitan train operator had failed.

2 It was a network-wide failure, which meant no trains could run in Sydney that day. Fortunately it was a Sunday so it was much less disruptive than if it had been a weekday.

When John got the call about the failure, he abandoned his family plans and rushed to the customer’s control room, where he worked alongside the customer’s CEO scheduling buses to ensure minimum passenger disruption.

When the network was finally restored, John turned to the CEO and said, ‘This is going to cost us, isn’t it?’

The CEO’s response was, ‘Let’s split the bus bill.’

What could have been an expensive, litigious conflict was resolved with a handshake in large part because John had shown empathy, accepted responsibility for the failure and given up his own time to help his customer in a crisis.

You can offer great service, but your service quality is only truly tested during the crisis of a service failure. The point of this story is to show that our employees stick by their customers whatever the situation, and they learn to do that through values stories. Delivery performance is what the client can count on; it’s part of the company guarantee. We can, and do, write all sorts of guarantees into contracts but the stories, and the reputation that goes with them, are more reassuring than the contract. I’ll return to values stories, with more examples, in the next chapter.

If you are wondering when your client sponsor should tell a values story, it is exactly at the point when people are saying (or thinking), ‘What if it goes wrong? If we embark on this project and it doesn’t work out, what’s going to happen?’ If your sponsor shares a relevant story at that point it will be highly persuasive. Here is an interesting thing, though. Your sponsor may not have the skill or inclination to tell your values story, but once you have shared the story, it will still work for you. Having heard the story, your sponsor will argue for your solution in a different way. They will be more committed to you. They will say something like, ‘Look, I really trust these guys,’ without knowing quite why, because the story had impact.

Values stories don’t have to be about recovering from a service failure, but they need to demonstrate how your people work and behave under pressure. The hospitality industry is awash with these stories. There are hotel chains that regularly collect values stories. I call them ‘lost wallet’ stories, like when a hotel guest left their passport or wallet in the hotel and the hotel clerk saw it and drove across town or to the airport to return it without asking for anything in return. These stories highlight the values of honesty and service.

A lot of companies think they can just mandate corporate values through mission statements. That is completely misguided. The CEO or the leadership team think up some motherhood values statements and post them on the walls. Those don’t persuade. They may even communicate the opposite sentiment if actions do not match the words. It’s stories of people (especially leaders) who live the corporate values that are truly eloquent.

The HP Way

Hewlett-Packard (HP) is a storied company in the information technology sector. HP people were famous for their proactivity and accountability. Their code of conduct was called the ‘HP Way’.

3 Their corporate tagline: ‘We trust our people.’

The history of that tagline goes all the way back to the company’s foundation in 1939, when it was a test equipment manufacturer. Every HP employee knows the story

4 of how co-founder Bill Hewlett came in to work on a weekend and found the equipment storeroom locked. He smashed the door to pieces with a fire axe and left a note on the smashed door, insisting it never be locked again

because HP trusts its people.

A story that shows how a leader behaves is worth more than any number of corporate values statements. Employees and customers are influenced by what leaders do to demonstrate values much more than what they say or write. It’s not an overstatement to say that story helped create one of the greatest companies of the 20th century, which in turn spawned the technology powerhouse of Silicon Valley. Steve Jobs got his first job at HP.

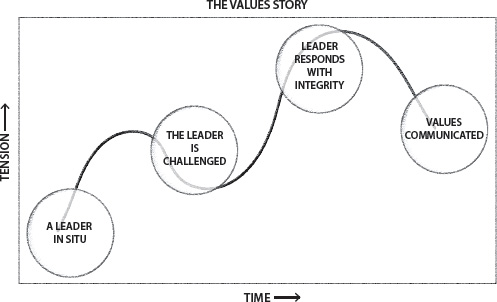

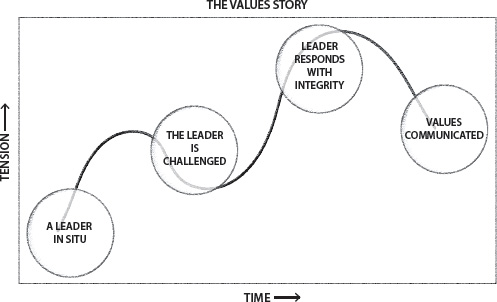

Figure 11.1: The Leader’s Test — values story structure

Taglines and mission statements mean nothing. Pages of tender responses about your company values are worthless. A true story means everything. When a leader demonstrates the values of their company through storyable action — we call that story triggering — those values become part of company lore. When leaders by their actions demonstrate the company values, employees and customers follow.

When leaders by their actions demonstrate the company values, employees and customers follow.

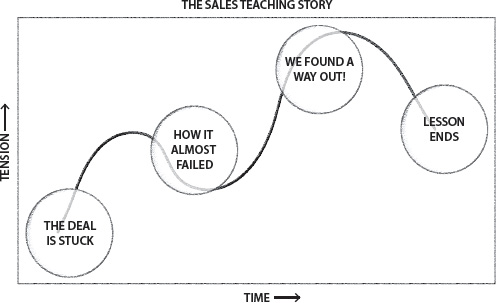

The second type of land story is the story that helps your future client through process aspects of the decision. This is the teaching story. What if the decision committee wastes time by worrying about things they need not worry about? What if there is an overbearing person on that committee who hogs the conversation and derails the process? How can I teach them to make the right decision?

Teaching stories are context specific. Typical obstacles that decision teams face when they have to make an important purchasing decision include issues such as lack of urgency, individuals delaying the process, inability to get agreement, standoffs within the committee due to personality conflict and turf battles over resource allocation. Each requires a targeted story.

The largest and most complex deals are normally closed by the most seasoned salespeople because they have the stories about how to close these types of deals. Often their skill is unconscious; they are unaware of the stories they have or how they use them. But when you know these stories exist you can seek them out and share them with your less experienced salespeople and your clients, particularly your sponsor, to help them resolve those closed-door internal decision issues.

The resident strong man

Before there was an iPod or iTunes

5, I pitched a music content platform to a large media company. It was a complex deal requiring the expertise of dozens of people from our company and a similar number from the customer. When we had locked down a viable solution and business model, it was time for the final price negotiation. Up to that point we’d worked with the customer team in a collaborative partnership.

That changed when the customer wheeled in their chief negotiator, a person we came to call the ‘resident strong man’ (we used a slightly different descriptor) because of his behaviour during the negotiations.

Picture the scene. All their many technical and business people down one side of a long table, a similar number of our experts down the other side, with negotiator at the head. As the negotiations commenced, strong man proceeded to pull apart the scope and business model. He demanded impossible quality levels and an unworkable business model. There were loud threats of legal action. We weren’t being collaborative anymore — this was nasty. I was used to ambit claims, but these demands were outrageous.

I remember walking disconsolately back to our office and confiding with a more experienced colleague that I thought the deal could not be closed.

‘Why not ring him up and request a private meeting?’ my colleague asked.

‘Really? I can do that?’ I hadn’t even thought of that possibility.

I rang strong man and arranged to meet him in his office, where we talked for two hours. I discovered he had a poor understanding of the project he was negotiating, a vulnerability I would never have guessed from his aggressive approach. So I shifted tactics and took the time to educate him. I explained why certain aspects of our tender were non-negotiable because they would compromise the outcome his company wanted to achieve.

It took several more full-scale meetings to close the sale, but the chief negotiator was no longer behaving badly, even though outwardly he was as tough as before. Subsequent meetings focused on the negotiable areas and we eventually struck a deal. Meeting the negotiator privately was the turning point. And finding a way to teach him how to close the deal without losing face in front of his team.

I’ve used that story to teach my salespeople how to ‘unstick’ negotiations and to help my customer sponsor do the same in their internal decision meetings (you can use this story too). It’s critically important to allow people to keep face when they need to back down from an untenable position. For this, privacy is paramount.

Your teaching story needs to match the situation you’re dealing with. It needs to convey the right emotion. In the resident strong man story, the chief negotiator was a bombastic person who had thrown himself into a situation he didn’t understand without knowing how to back out of it. We needed to manage his potential embarrassment and loss of face.

With an urgency problem, we need to create a sense of urgency and make people feel the loss they would experience if they missed the opportunity. People don’t like to lose a negotiation, but they often don’t appreciate what’s at stake when they can’t come to a decision. Fear of loss and urgency can be conveyed in a story. And the strange thing about urgency stories is they don’t need to be about your specific business; you can generate the urgency emotion with an analogous story.

A real estate company I’ve been working with is operating in a hot market that is peaking. Prices are starting to fall, but prices have risen spectacularly over the past few years so the tendency for the seller is to hold out for an unrealistic price and fail to sell. That attitude could be expensive for the property seller, but it’s a difficult situation for the real estate agent. The agent’s opinion, assertions and advice will not be heard because of a perceived conflict of interest. What’s needed is an urgency story. I told them the following story from my personal experience.

The pink house story

The suburb I live in has an unusually high level of house reconstruction because the land value is so high. In our street almost every house has been demolished and replaced with a modern house sporting a basement carpark, wine cellar, cinema and private lift. In 2014, two neighbouring, similar houses were sold and demolished to clear the way for construction of new houses. The average sale price was $4 million on an average lot size of 600 square metres.

The builder at property A used a construction method I’ve not seen before: modular formwork for the concrete walls that was quick to erect. The house flew out of the ground. It was finished to a high standard and sold nine months after demolition for $9 million in a hot market in 2015.

The builder at property B is still on the basement after three years of construction. Which is just great for the neighbours (not)!

Setting aside the aggravation for the neighbours, think about the financial cost of building a house that slowly. The time value of $4 million is $160,000 a year at current interest rates — that’s what a mortgage would be costing. If it had been completed two years ago and rented, it could have returned $250,000 a year in the current stable rental market. But the biggest ‘cost’ is likely to be in the house value, if it is sold on completion. Property B could easily sell for less than property A because of a cooling market. A $2 million loss looks quite likely.

Owner B is likely to lose a minimum of $1,250,000, and probably much more, just because of the delay. People don’t think carefully enough about the cost of time.

The key criterion of the teaching story is it must match the emotional situation. It doesn’t have to be exactly the same situation, but it must deliver the emotional impact of that situation. It also must convey insights about human behaviour. The resident strong man story conveys insights about saving face; the pink house story conveys insights about the value of time, highlighting the cost of delay.

Most people don’t think about the financial impact of choosing a slow builder. They’re focused on who will deliver the best finished product or the lowest total cost. Choosing the slow builder adds significantly to the overall cost, and choosing a faster builder frees up more money to spend on fixtures and fittings. You can buy quite a lot with $1,250,000.

Figure 11.2: The Sales Teaching Story — a problem-solving journey

Keep connecting in the decision phase

Maybe you agree with me about hook stories that connect and fight stories that differentiate, but you don’t agree with this landing the deal stuff. You may think, for example, that telling a story about how your company dealt with a screw-up is too risky. Even to hint that things could go wrong is unwise. Or you may think it’s inappropriate to try to influence matters during the customer’s decision phase. ‘We should just let the client get on with the decision and not interfere.’

My experience is that if you don’t exert any influence through the decision phase, you increase your client’s chances of not getting their best result. My first story in the Land phase about failing to sell a telecommunications system (the Hell’s Gateway story) is a prime example. The client did not choose the best solution and I could have helped prevent that poor outcome. If you’re confident that your solution is best for your client, you should be confident to continue exerting influence all the way to contract signature. Otherwise you and your future customer will lose out.

If you’re confident that your solution is best for your client then be confident to exert influence all the way to contract signature. Otherwise your client will lose out.

Is there a risk of telling the wrong teaching story? Can we mess it up? It depends on how well connected you are with your sponsor, but teaching stories are low risk for a couple of reasons. The first is people often don’t notice stories. When you tell a teaching story there’s a reasonable chance that the message gets through to your sponsor’s brain and they don’t realise you’re influencing them. That’s the magic of stories. If your story misses the mark, then there is nothing lost; it’s like you said nothing. The second reason its low risk is there’s nothing malicious about your story. Your intent is ethical. You’re telling the story to help your client solve a problem. I put on my best sales manager voice and deliver the teaching. ‘Your situation reminds me of when…’ I’m teaching them how to sell. You’ll be amazed at how well this works.

There’s a saying the best sales managers know: ‘You need to teach your client how to buy and you need to teach them how to sell.’

6 Teaching them how to buy means showing them why they should buy your products and services. Teaching them how to sell means showing them how to get the decision made in their organisation.

To summarise, the three critical activities to get you through this difficult period of landing the deal are:

1. Tell your values stories to help allay the perception of risk.

2. Use your sales management skills by telling sales teaching stories to smooth the decision process.

3. Reiterate your insight and success stories. ‘Others have done it, and done it successfully. So it’s not a big risk to change.’

These activities will guide the decision team through the process to make the right decision. We’re talking here about landing the big deal, and big deals — even in big companies — happen rarely. When they do, we celebrate. Champagne bottles lined up, every-one’s congratulating you. You’re the hero. You made it happen. It wasn’t obvious how you did it. Your stories worked invisibly and subtly in the background, so you’re a magician! More importantly, you won a deal that your competitors might have won. You’ve taken business from them, and your client got the value of your products and services, a real solution to their problem. It’s a tremendous win. Let’s celebrate!

Now you understand exactly what values and teaching stories are. In the final chapter we learn how to prepare your own land stories.