CHAPTER 2

FROM THE OUTSIDE

WHAT IT'S ALL ABOUT

- The importance of segmenting the industry

- The concept of industry attractiveness

- The macro forces that shape industries

An organisation does not operate in a vacuum. Any strategy has to fit with the characteristics of its external environment, so let's begin from the outside. Given that multiple aspects of the environment could be evaluated – customers, markets, competitors, regulations, societal trends – where should you start? Clearly, a certain amount of data is needed to familiarise yourself with the environment, but how much should you collect?

Focus on data that answer a few basic questions about the environment:

- What industry are we in? Before diving into a detailed assessment it's important to define what industry segment you are in. This often turns out to be more difficult than you might think.

- How attractive is it? The opportunities offered by the industry will have a big impact on how successful an organisation can be. Some industries are so attractive that just being in them is enough to make a firm successful. Others are so tough that only one or two competitors make adequate returns.

- What is the broader context? It is increasingly important for strategists to understand the broader context in which their organisation is competing. The attractiveness of a business and what it takes to be successful in it are influenced by broad trends such as climate change, changing government policies, and the emergence of new consumer concerns and pressure groups.

Answering these questions to flesh out your starting position can take time, but it is often where a lot of the heavy lifting is done – the 95% of a decision that is perspiration rather than inspiration. Fortunately there is a host of approaches, frameworks and tools to help.

WHO SAID IT...

“The essence of formulating competitive strategy is relating a company to its environment.”

– Michael Porter

DEFINING INDUSTRY BOUNDARIES

Organisations operate in distinct environments. Barclays Bank does not operate in the same business environment as Ford. Economists call these ‘industries’ – the environments within which a set of collaborators and competitors pursue their activities. In general, industries include a number of competitors, although a few are monopolies. Industries can be populated by not-for-profit organisations, for example, charities which compete for funds. What it takes to win will vary from one industry to another – the rules of the game for banking are different to those for the car industry.

WHO SAID IT...

“. . . the key aspect of the firm's environment is the industry or the industries in which it competes.”

– Michael Porter

However, it can be difficult to define the boundaries of an industry. Where does one industry stop and a new one begin? In the car industry, which is used as an example throughout this chapter, the rules of the game are different for luxury cars, small cars, MPVs (multi-purpose vehicles), SUVs (sports utility vehicles), family saloons and vans. They also vary by country – the Chinese market is different from the US market. In fact, the car industry could be seen as many different industries, albeit with some common features.

At this point, let's explore our first strategy concept: segmentation.

SEGMENTATION

Segmentation involves dividing up an industry into subindustries, each of which is different on one or more of the following key dimensions:

- The growth rate.

- The inherent profitability.

- What it takes to win – sometimes described as ‘sources of competitive advantage’ or ‘rules of the game’.

Segmentation is a critical first step in analysing the external environment because if you don't know the industry you are in it is impossible to begin to create a sensible strategy.

For example, if you were asked to describe the car business overall you might think (considering the above dimensions) that the growth rate was low, the inherent profitability was low (due to it being cyclical and competitive) and that the rules of the game were to be a low-cost, global giant like Toyota, Ford or Volkswagen – But the SUV business in the US was, until recently, both fast growing and highly profitable. And winning in this segment required a US rather than a global presence. So if a car manufacturer only evaluated the industry at the level of ‘cars’, it would overlook the major differences between what was happening in the SUV segment vs. the car industry in general.

Segmentation is not only useful for analysing your current business, it can also be a creative activity, leading to new insights that improve existing strategies or even give rise to whole new businesses. For example, consider the insurance business. Traditionally this was segmented along product lines, such as motor vs. household insurance. But it can also be segmented by sales channel, e.g. via a sales force, via agents, either direct or through comparison websites. Growth rates, profitability and what it takes to win often vary more across channels than across products.

The insight that insurance can be segmented by channel has made it possible to create completely new types of insurance company. For example, Direct Line, became the first UK insurance company to use the telephone as their main channel of communication. Starting in 1985 with 65 employees, it now employs 10,000 people and is the recognised industry leader. More recently, the emergence of another new channel, price comparison websites, has allowed new insurance companies to set up with very low overheads, selling insurance at low prices. Segmenting by channels is now recognised as one of the key ways to understand the market for financial services.

Despite its fundamental importance to strategy-making, segmentation can be difficult and many organisations get it wrong. For example, Volkswagen was the undisputed early leader in the Chinese auto market: in the mid 1990s it had a 50% market share. Its management segmented the market according to products – designing their strategy around choices about which type of vehicles to sell. But this segmentation failed to take account of the major changes in the market during the late 1990s. Early on its main customers were state-owned enterprises, who could be marketed to through the contacts held by Volkswagen's joint venture partner, Shanghai Automobile Industry Corporation. However, as China's economy exploded, retail customers became a more important part of the market. To access these customers required a completely different marketing approach and sales and service network. Segmenting the market by product rather than customer, Volkswagen missed this change, allowing its rivals to build stronger positions.

Note that industry segmentation is not the same as ‘customer segmentation’, a market research technique that seeks to identify groupings of customers who share common purchasing criteria. Industry segmentation is about dividing up industries according to attractiveness and what it takes to win. For example, when buying cars, young men and young women may belong to different customer segments, with different purchasing criteria, but they are not regarded as separate industry segments because they are not distinctive enough in terms of the rules of the game, growth or profitability.

Another related concept is that of the ‘strategic group’. This is a sub-group of competitors in an industry who compete with each other. For example, within the restaurant industry McDonald's competes with Burger King in one strategic group, while local fine dining establishments compete in another. The difference between the concepts of segmentation and groups is that the latter assumes that the company operates in only one business, whereas the concept of segmentation is more flexible. For example, McDonald's competes in two different segments with its burger restaurants and its McCafé coffee shops. This makes it tricky to decide which group it competes in.

HOW TO SEGMENT

Segmentation is often tricky in practice. For example, on what dimensions should you segment the automotive industry? By product (e.g. luxury vs. small cars), by customer type (e.g. fleet sales vs. sales via dealers), by country (e.g. US vs. China), or by type of service (e.g. new car sales vs. servicing). How finely should you segment? For example, should you segment customer types by fleet vs. dealers, or should you sub-divide fleet customers into further segments based on the number of cars purchased, or the typical purchasing behaviour?

In theory, you can segment most businesses into hundreds or thousands of units. There is even a ‘segment of one’, where every customer is regarded as a different segment. But segmenting too finely can hide important linkages. Global car firms such as Volkswagen, Ford and Toyota may be in many different segments, but these segments are linked because they often share common manufacturing facilities, R&D or dealer networks.

HOW YOU NEED TO DO IT

Segmentation is partly a creative act but also something that can be learned. To segment an industry it can be helpful to begin with the following process:

- Find alternative ways to segment the industry. Normally this will be by customer need, type of product/service, or stage of the value chain.

- Choose a segmentation level which helps you focus on the decision that you need to make.

- Check that the segmentation is neither too detailed, nor at too high a level.

DEVELOPING ALTERNATIVE SEGMENTATIONS

There are normally three ways to segment an industry: market/customer, product/service and value chain, summed up in the more memorable phrase: ‘Who? What? How?’ A useful first step when segmenting is to brainstorm alternative ways to segment on these dimensions.

Market segmentations can be in terms of geography (e.g. Asia, China, region, city), customer type (e.g. state-owned enterprise vs. consumer), channel (e.g. dealer vs. direct sales) or customer needs (e.g. commuting vs. family trips).

Alternative market segmentations can be derived from changing the level at which the segmentation is made. For example, ‘state-owned enterprise’ is a very high level – one that is appropriate for discussing major strategy alternatives with head office. For a more detailed strategy it would be worth segmenting state-owned enterprises further – for example, according to the typical number of vehicles they purchase, or whether they buy on the basis of price or relationships.

Product segmentations can also be done in various ways. In the Chinese automotive market, product segmentation could be by the overall type of vehicle, e.g. commercial van vs. passenger vehicle vs. light truck. They might also be divided by price point. As with customer needs, the segmentation could be kept at this level for a strategic debate about the overall strategy for China but broken down into a finer level of detail for a more detailed discussion of the manufacturing strategy.

Customer and product segmentation are the most common but sometimes it is appropriate to segment by different stages in the industry, often described as the ‘value chain’. For example, the automotive industry value chain includes parts manufacture, assembly, sales and service, each of which could be a different segment with different ways to win and levels of profitability. Different levels of value chain segmentation are possible. For example, the parts manufacture segment could be divided by the major components of the vehicle – gear box, engine, body parts, axles – each with its own growth rates and competitors.

Segmenting on these three dimensions can lead to any number of potential segmentations, which is clearly not practical. The next step is to pick the most useful segmentation.

PICKING A USEFUL SEGMENTATION

The choice of segmentation should support the strategic decision to be made. (If there is no decision, then there is no strategy or segmentation required!)

For example, assume that you are the head of Volkswagen's Chinese business. You need to make decisions about Volkswagen's strategy over the next three to seven years. This involves major choices about which customer, product and parts of the value chain to focus on. Therefore a high-level segmentation that captures the major choices is probably appropriate, for example:

- Customer segments: state-owned enterprises and end consumers.

- Product segments: cars, vans, trucks. For each of these segments, high vs. low price.

- Value chain segments: parts manufacturing (outsource vs. manufacture in house), assembly (outsource vs. in house), sales (own sales force vs. dealer network).

Assume that the outcome of this high-level strategy process is a decision to focus on selling low-priced cars (from the analysis of the product segmentation) to retail customers (customer segmentation), and to assemble the cars from outsourced parts, selling and servicing them through an independent dealer network (value chain segmentation). The next decision facing the company is which regions to operate in and precisely which customers to target. This requires a new level of segmenting on these two dimensions. For example, each region could be analysed as a segment. End-consumers could be segmented according to their income levels or whether they live in the city / countryside, because it is at this level that you need to make decisions.

HOW YOU NEED TO DO IT

Checking Your Segmentation

If you feel unsure or lack experience in segmentation, check to ensure that the segments that you have created are neither too detailed nor at too high a level. The following questions can help you assess the degree of difference between two segments. This will give you a general sense of whether to treat them as one segment, or split them into two. Do the segments –

- Have very different growth rates?

- Vary significantly in the average profitability of all competitors?

- Have major differences in industry structure? (More on this when we discuss the five forces):

- Are customers different in the two segments? Do they have very different purchasing criteria – for example, are customers in one segment more focused on price while others are more focused on brand or product design?

- Are the suppliers different in the two segments?

- Are there different potential substitutes for the products in each segment?

- Have different ‘ways to win’ or sources of competitive advantage? For example,

- Do they have different competitors?

- Is your market share or that of competitors in each segment very different?

- Are the assets and capabilities required to compete in each segment very different?

- Are the cost structures in the two segments different?

- Are there significant barriers preventing a competitor in one segment entering the other?

- Is your profitability and market share very variable across the two segments?

For example, there are currently significant variations between different regions of China. Markets are growing at very different rates and it is possible to be strongly positioned in one region while being unsuccessful in another (i.e., they have different sources of competitive advantage).

If the segments you have created do not differ significantly on these dimensions, you might consider consolidating them in order to simplify your strategy. For example, you could start by segmenting by region but then decide instead to divide China into four mega-regions, e.g. South, Shanghai, Beijing and Inland – because differences within these mega regions were not significant enough to warrant a more detailed analysis.

Note: there is a Catch 22 involved in segmentation. You need to segment the market before you can truly understand its growth rate, inherent profitability and the way to win – but you must first understand what drives attractiveness and what it takes to win before you can come up with a sensible segmentation. For this reason, segmentation is often done iteratively, with a mix of intuition and analysis, trial and error. It is one of the hardest topics to learn and requires plenty of practice.

INDUSTRY ATTRACTIVENESS

One of the fundamental questions in strategy is: ‘Where to invest?’ An important first step is to evaluate the attractiveness of different segments – defined here as how attractive it would be to be a typical competitor in that industry or segment. It has three components:

- Size. All else being equal, it is preferable to compete in a large segment.

- Growth. High growth businesses are not only on their way to becoming bigger, they tend to be more profitable as there is less fighting over market share.

- Average profitability. Some industries are inherently more profitable than others.

For example, in the automotive business the small car segment is large and growing, but generally highly competitive and characterised by low margins. The market for luxury cars is smaller but profitability is higher.

Normally it is possible to find data on size and historic growth. There are exceptions, particularly in exotic segments such as fuel hoses for military aircraft, or speciality food additives. In such cases it may be necessary to do some modelling of the size and growth of the market, e.g. trying to estimate the number of customers, customer growth rate, and what each customer purchases on an annual basis.

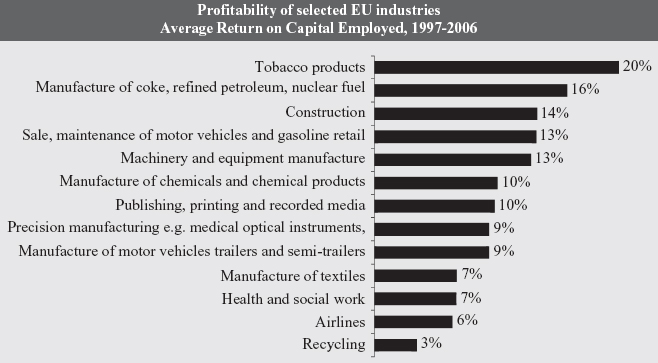

Differences in profitability across selected industries

The hardest thing to estimate is often the profitability of a segment. However, as the exhibit shows, there are wide variations in the profitability of different industries, which become more pronounced if industries are segmented more finely.

So it is often necessary to spend some time analysing segment or industry profitability. To do so use a mix of the following approaches:

Identify your own profitability by segment. The advantage of this approach is that the data is usually available. Unfortunately, it won't be a reliable measure of industry segment profitability as it is affected by other factors, such as your competitive position and operating efficiency. Remember, attractiveness is defined as the attractiveness of being a typical participant in the segment. If you are not ‘typical’ then your profitability will not be an accurate estimate of the average for the segment.

Identify the profitability of a range of competitors. This can be insightful but requires you to find competitors who compete only in one segment, or report data by segment, which is rarely the case. If it is, count yourself lucky. Analysing the profitability of your competitors is a useful benchmark but rarely provides reliable data on which to base major strategic decisions.

Estimate the likely profitability of the segment by considering overall ‘industry structure’. Generations of industrial economists have studied what makes some industries more profitable than others. They observe how differences in industry structure (i.e., the mix of suppliers, customers and competitors, and the way they interact) lead to different outcomes for customers and competitors. For example, monopolies lead to high profits for the competitor but a bad deal for customers. Commodity industries, where the product is sold on price, are generally less profitable. Economists have developed some useful rules of thumb that can be used to make an estimate of the likely profitability of an industry segment. So, for example, profitability tends to be lower where there are more competitors in a segment, or when customers are more price-sensitive. The simplest approach is to use a categorisation of types of competitive environment, such as that of Saloner, Shepard and Podolny, from their book Strategic Management, which characterises types of environment in order of increasing segment profitability:

- Perfect competition. Lots of competitors are selling commodity products to price-sensitive customers. An example would be petrol retailing or farming of commodity products such as wheat.

- Niche markets. Competitors are competing in separate niches, so although there is competition, there aren't too many competitors in any one segment. An example would be luxury goods such as fine wines or high end luggage.

- Oligopoly. There are only a few competitors. These may learn to avoid excessive competition, for example by avoiding attacking each other's core markets, or by not starting price wars. Examples include some electricity generation markets (where there are not many competitors), or UK cinemas (which all show the same films at similar prices)

- Dominant firm. One competitor is strong enough to dictate terms to the industry, such as in pricing and capacity expansion. An example would be retailing of gas and electricity in the UK – British Gas is often the first to announce a price change and regarded as a price benchmark for other competitors.

- Monopoly. There is only one competitor, who can therefore do largely as it wishes – such as charging high prices. An example would be Microsoft in operating systems.

Industries may not fall into one distinct category. There may be, for example, some competitors in retail electricity who cut prices to gain market share, even if British Gas has not done so. But industries often tend towards a particular model and this will provide a clue as to their profitability. However, it is at best a crude way of estimating likely segment profitability.

THE FIVE FORCES

A more complex but rigorous approach is to use Porter's five forces framework to analyse the profit potential of an industry or segment. According to Porter, five forces determine industry profitability: the threat of substitute products or services, the threat of new entrants, the bargaining power of suppliers, the bargaining power of buyers, and rivalry among existing competitors.

To think about how these forces affect profitability, consider what would happen in an industry were profitability to rise, for example, if all competitors were to put their prices up 20%. In an attractive industry, the extra profits would go to the incumbent competitors because the five forces are favourable (i.e., they all have limited impact). For example, in the tobacco industry:

- To a smoker, there is no effective substitute for tobacco. There is no risk that a rise in prices will lead to a major switch by customers from tobacco to a substitute product.

- There is a low threat of new entrants because there are very high barriers to entry – it is expensive to launch and distribute a new tobacco brand. This prevents others from entering the market to take a share of the extra profits.

- The most important suppliers to the tobacco industry are primarily farmers who have little negotiating power with corporations such as Philip Morris, and are thus unable to get a share of the extra profits.

- Similarly, buyers of tobacco products are a fragmented bunch with little bargaining power. Since the end user is loyal to one brand, even large retailers cannot credibly threaten to stop buying from a major tobacco firm.

- There is limited idustry rivalry because there are relatively few competitors. Also, they tend not to compete on price because it would not prompt a lot of end users to switch brands. Hence a price war would not benefit anyone.

In contrast, in an industry that is unattractive, the forces would be unfavourable to incumbents. This could result in the increased profits going to the customer, either because the incumbents embark on a price war (high rivalry), or because the customer has strong bargaining power, or because there are credible substitutes that the customer can switch to if prices rise. Alternatively, the profits could go to suppliers (if they have strong bargaining power) or to new entrants (if there are low barriers to entry). For example, the European airlines business has low profitability because there is a high level of rivalry (due to overcapacity, a high proportion of fixed costs and price competition), and a credible threat of new entrants (several budget airlines have set up in recent years).

WHO YOU NEED TO KNOW

Michael Porter is the world's most well-known strategy academic. Born in 1947, Porter achieved high academic honours first at Princeton and subsequently at Harvard Business School, where he is currently a professor. He is also co-founder of a management consultancy, Monitor, and an adviser to governments and companies.

One of his great achievements was to be the first to summarise in a digestible format the work of others. He consolidated decades of work by industrial economists such as Ed Mason and Joe Bain, who had studied how differences in the structure of industries – for example the number of competitors, the relative size of customers and competitors, and the existence of barriers to entry – affect profitability. Much of this work was done to understand how to prevent firms asserting monopoly powers and extracting ‘unfair’ profits. In Competitive Strategy, Porter turned this idea on its head to create the five forces framework to help companies understand the conditions under which industry structure could help them enjoy higher profits.

His next work, Competitive Advantage, articulated and made accessible to a broad audience the concepts of competitive advantage, the difference between competing on cost vs. differentiation, and the value chain. More recently he has applied these ideas to a range of issues, including the competitive advantage of nations and healthcare policy.

Although criticised for not reflecting ‘softer’ influences on strategy, such as cooperation, culture and government and societal pressures on business, Porter remains the greatest exponent of the economic theories that underpin strategy.

Beyond simply assessing the profit potential of the current industry or segment, Porter's five forces provide a foundation for analysing other aspects of the situation, such as the sources of competitive advantage and insights into how the industry may evolve. For this reason, it is a useful analysis to apply early on when devising strategy in a competitive industry.

To do a five forces analysis, first assess which are likely to have a big impact on industry profitability. The following checklist may be helpful:

The threat of substitute products or services is high when:

- substitutes have competitive price and quality;

- buyers face few switching costs.

The threat of new entrants is high when there are:

- few economies of scale;

- limited experience or learning curve effects;

- limited product differentiation;

- low capital requirements;

- low switching costs;

- ready access to distribution channels;

- limited advantages for incumbents from other sources, e.g.:

- proprietary product technology;

- favourable access to raw materials;

- favourable locations;

- government subsidies.

The bargaining power of suppliers is high when:

- there are few suppliers and they are more concentrated than the industry they sell to;

- they are not obliged to compete with other substitute products for sales to the industry;

- the industry is not an important customer of the supplier group;

- the supplier's product is an important input to the buyer's business;

- the supplier group's products are differentiated or have built up switching costs;

- the supplier group poses a credible threat of forward integration.

The bargaining power of buyers is high when:

- buyers are concentrated or purchase large volumes relative to seller sales;

- the products buyers purchase represent a significant fraction of their costs or purchases;

- the products buyers purchase are standard or undifferentiated;

- buyers face few switching costs;

- buyers earn low profits;

- buyers pose a credible threat of backward integration;

- the industry's product is unimportant to the quality of the buyers’ products or services;

- the buyer has full information.

Rivalry among existing competitors is high when there are:

- numerous or equally-balanced competitors;

- slow industry growth;

- high fixed or storage costs;

- limited differentiation or switching costs;

- diverse competitors;

- high strategic stakes;

- high exit barriers;

- capacity is augmented in large increments.

Having assessed these factors, integrate your thinking into a judgement about the effect of the forces on overall industry profitability. It may be helpful to think of the earlier chart which showed the profitability of different industries. Is your industry more like tobacco (highly profitable) or more like the airline industry (highly competitive, low return)?

ISSUES WITH USING THE FIVE FORCES FRAMEWORK

Porter's five forces framework is an extremely useful tool for understanding the factors driving the profit potential of an industry. However, one source of frustration is that it does not provide a quantitative answer; ultimately a judgment is required. Of course, you can and should check that whatever data you have about profitability is consistent with the five forces analysis, but it's not the same as being able to precisely model industry profitability. Numerous attempts have been made to come up with a tool that does this, but they have largely failed.

There are some exceptions. In commodity businesses such as minerals or electricity generation, for example, it is possible to draw supply/demand curves to estimate the likely price and thus the profitability of an industry. It may be that your particular industry is amenable to such an analysis, or an alternative quantitative analysis. Even if no firm predictions can be made, such models can provide support to or challenge more qualitative approaches, such as the five forces.

Various other issues can trip people up when estimating industry and segment profitability. The first is that they are not clear about what is meant by ‘segment profitability’. They often confuse this with ‘our profitability in this segment’, assuming, for example, that highly profitable products must be in attractive segments – when you may be profitable because you have a very strong competitive position albeit in an unattractive segment. As mentioned, Porter's five forces gives an insight into the potential profitability of a general participant in the segment – not that of a specific competitor. The important point to remember is that the overall profit potential, size and growth of a segment is independent of your own position in that segment.

Another issue is that the concept of ‘industry attractiveness’ works best when the different players face a similar industry structure. For example, all major car companies have a common customer base, common suppliers of raw materials such as steel, and common barriers to entry. When there are few competitors, or these competitors face very different industry structures, then each may exist in a ‘micro climate’ where the industry structure is unique. For example, some airlines have strong unions (suppliers of labour), others do not, so the five forces analysis cannot simplistically be applied at the industry level. If there is no ‘typical’ competitor, an analysis of the industry can be difficult. Fortunately, the five forces can still be used to evaluate the likely profitability of a company's individual position, but it will have to be tweaked to assess the individual situation of each company, making the application of the framework more complex. Nevertheless, the insights derived from the forces shaping profitability will still be valid.

A particular limitation is that, unlike many of the strategy concepts and tools discussed in this book, the concept of industry profitability is not easily transferable or relevant to all not-for-profit organisations. The concept of ‘industry profitability’ is not easily applicable to a charity (unless it is competing in an industry such as with charity shops). However, the more general concept of ‘attractiveness’ remains relevant. For example, if you are a charity that is dedicated to improving the lives of poor children, there are many ‘segments’ you could operate in – different countries and different services, such as water supply, education, food programmes, career development, etc. Each can be evaluated in terms of attractiveness by considering the degree to which operating in those segments would contribute to improving the lives of poor children (the equivalent of ‘potential profitability’ for a profit seeking entity). Would a pound spent on education have more impact than a pound spent on water supply? The basic notion of ‘attractiveness’ remains relevant for a charity, even if it is defined in a different way.

THE MACRO-ENVIRONMENT

In many industries, the role of external factors beyond rivals, new entrants, suppliers and buyers can have an important influence on strategy. For example, government regulations, public opinion and pressure groups can be influential.

Some argue that such influences, referred to by Porter as the ‘macro-environment’, can best be evaluated by thinking of how they affect market forces or ‘microenvironment’. Consider the influence of governments on the airline industry, for example. Laws that restrict foreign companies operating in and out of a country raise barriers to entry and reduce the number of rivals. The regulation of airports limits the ability of these potentially powerful suppliers to negotiate profits from the airlines. For example, the owner of Heathrow airport could earn a fortune by auctioning slots but is prevented from doing so by regulation.

But the macro environment does not always operate through the market forces of the micro-environment. For example, volcanic ash clouds from Iceland affected the entire airline industry – but not through any of the five forces. Public anger in the US over the BP oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico similarly had a major effect, but not through the marketplace.

For such influences it can be helpful to use a different framework to evaluate the effect of broader forces on the organisation. The most common form of analysis is PEST or PESTLE analysis, which stands for:

This simple structure will help you to collect information on these various environmental forces; the key then is to derive their implications for the organisation. This can be done in two complementary ways. The first is to think about how they impact the five forces. The second is to ask if they will have any other effects that could occur not through the process of competition but by some other mechanism, e.g. government fiat, the force of public opinion, or an act of God.

Frameworks similar to PESTLE analysis can be useful. A common one is ‘country risk analysis’, which seeks to describe the general factors at play in a particular country. This can be particularly helpful if you are considering a major overseas investment. In effect, it is a type of PESTLE analysis customised to the issues typically encountered when making investments in unfamiliar or risky markets.

These might include:

- economic uncertainties (e.g. growth, inflation);

- sovereign risk (risk that the government might default on its debt and other agreements);

- political uncertainties;

- foreign exchange transfer restrictions, including restrictions on dividend repatriation;

- exchange rate volatility including the risk of a revaluation;

- taxation policies and risk of retroactive action;

- regulatory and legal uncertainties;

- risks of conflict (civil war or other types of unrest);

- level of corruption.

As with PESTLE analysis, think through how these factors will influence the industry's growth rate and profitability.

Country analysis is often customised to the context. For example, if you are investing in a power plant in a developing country, factors such as the legal enforceability of fuel supply contracts and the reliability of the electricity transmission structure will be particularly important. The aim is to come up with a customised approach rather than to simply consult standard credit risk reports (which tend to be about specific issues such as the creditworthiness of government debt).

WHAT YOU NEED TO READ

- For a worked example of how to apply the tools in this chapter (and subsequent chapters), see www.whatyouneedtoknowaboutstrategy.com.

- One of the few practical guides to segmentation is Chapter 2 of Richard Koch's book, The Financial Times Guide to Strategy, Pearson, 2006 (also on Google Books).

- The original five forces framework was published in Competitive Strategy by Michael Porter, Free Press, 1980. An update can be found in ‘The Five Competitive Forces That Shape Strategy’ in the Harvard Business Review, January 2008.

- Robert Grant's Contemporary Strategy Analysis, John Wiley & Sons Ltd, 2010 has two chapters in part two discussing Industry analysis.

- Consolidated views of free online information are available through Companies House and the British Library. It is also possible to access paid databases of industry and economic trends (e.g. Oxford Analytica, Strategy Eye) as well as specialist research databases (e.g. Nexis Lexis, Infotrac) and analyst sites such as (in the IT sector) Gartner and Forrester.

- Specialist portals provide a single point of entry to appropriate sources of information on specific topics, such as EBSCO's EDS and British Library's Resource Navigator that help to access resources on strategy, the Ashridge Virtual Learning Resource Centre for management development and leadership, and the DTN ‘scenario console’ for a unique snapshot of current trends.

IF YOU ONLY REMEMBER ONE THING

Before you start to analyse your own organisation, step back and look at the external environment.