5

Black Holes Just Wanna Have Fun

Orbiting high above Earth, one-third of the way to the moon, is the Chandra X-ray Observatory satellite. The observatory is named in honor of Indian American Nobel prize-winning astrophysicist Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar (or, Chandra, which means “moon” or “luminous” in Sanskrit). In 1930, when he was just nineteen years old, he calculated that white dwarf stars could not exceed a certain mass—now accepted to be around 1.4 times the mass of the sun. Once the dying star exceeded this limit, which came to be known as the Chandrasekhar limit, the object would no longer be able to resist the force of gravity. It would explode in a fiery supernova. The remote-controlled Chandra observatory carries a telescope specially designed to detect X-rays from very hot regions in the universe: supernovas, galaxy clusters, and the stuff around black holes.

The crew that launched the Chandra X-ray Observatory took a series of photos, including this one, of the satellite telescope as they launched it into space. Chandra weighs 50,162 pounds (22,753 kG). In the background is planet Earth, at an angle that shows a desert area of Namibia in southwestern Africa.

In 2015 Eric Schlegel, an astrophysicist at the University of Texas in San Antonio, was looking at some archived data from Chandra. It showed a small galaxy, NGC 5195, merging with a much larger spiral galaxy NGC 5194. Spiral galaxies are named for their distinct spiral shape, in which stars, gas, and dust are gathered in spiral arms that spread outward from the center. Located 26 million light-years away, in the Hunting Dogs constellation, the larger galaxy is nicknamed the Whirlpool because of its curving spiral arms. Like a whirlpool, it is slowly drawing its companion galaxy into its center. This little dance has been going on for hundreds of millions of years. The Whirlpool will eventually swallow its smaller partner.

Schlegel noticed two boomerang-shaped arcs of X-ray emission close to the center of NGC 5195, the smaller of the two galaxies. The arcs, Schlegel and his colleagues guessed, indicate burps of gas from the Whirlpool. The curves mapped right back to the home of the black hole at the center of the galaxy. Because of the amount of belched gas, Schlegel thinks that a lot of matter must have been dumped very quickly into the black hole at the center of the Whirlpool—and been kicked out just as quickly. It’s as though you chugged a soda much too fast. Like the Whirlpool, you belch a lot of gas quickly after drinking the soda.

These images from Chandra and Hubble show two merging galaxies (NGC 5195, top left, and NGC 5194, bottom left) within the larger Messier 51 galaxy. The bright whitish-blue outburst at the center of the blue inset at right is the galaxy’s supermassive black hole. Two boomerang-shaped arcs below it are burps of gas from NGC 5194.

The X-ray arcs represent cosmic fossils from two enormous blasts from the Whirlpool that happened millions of years ago. The arcs of X-ray emissions would have taken one to six million years to reach their current positions. The radiation would have taken another twenty-six million years to reach us.

That was interesting enough, but then Schlegel compared the emissions to some twenty-year-old data of the same region. These were from an optical telescope at the Kitt Peak National Observatory in Arizona. In the older image, he found two slender emission lines of relatively cool hydrogen gas just outside the X-ray arcs. Together, the X-ray and optical images told a story. As the two X-ray shocks traveled outward, they snowplowed hydrogen gas from the center of the NGC 5195 galaxy off to the sides. “Thank goodness for archives,” he said. “It was picture perfect.” The images clearly supported the hypothesis that black holes do indeed belch. In fact, Schlegel thought he must have been cherry-picking the data. He wondered if he was acknowledging only the evidence that supports a hypothesis—and ignoring the rest. “I’d never seen anything work out that well,” he said. “Usually, if you’re at the edge of a research frontier, there’s a lot of noise. You spend a lot of time squinting and thinking, ‘Is this really something?’”

Schlegel walked away from the data for a couple of days and then came back. He carefully walked through every step of the data and came to the same conclusion. The X-ray burps had indeed plowed through hydrogen gas at the center of the galaxy, pushing the gas to the outer edges. This hydrogen gas was a stellar nursery!

If you live in a part of the country with snowplows, you’ve seen the huge mounds of snow they form at the sides of the road. Just as snow plowed to the edges of the street can form dense snow-packed hills, the X-ray blast waves created areas of hydrogen gas dense enough to form stars farther from the center of the galaxy. And Schlegel and his team have found what appear to be new stars forming at the outer edge of the blast wave from the Whirlpool.

Schlegel and others believe this kind of black hole behavior probably happened very often in the early universe. The black holes shaped the evolving structures of galaxies. But it’s rare to catch them in the act. “If you look at a true color image of a spiral galaxy, you immediately see that the outskirts are relatively blue in color,” Schlegel said, “and the nuclear [interior] region is relatively orange.” That blue radiation tells us that stars in the outskirts are younger, because young stars tend to be more massive and hot, and stars tend to form on the arms of spiral galaxies.

The orange stars in the interior pose more of a puzzle, Schlegel said. Stars don’t seem to be forming there. “You could just imagine that you’ve got older stars [in the interior], but we think that galaxies are formed at roughly the same time. The stars in the nuclear region ought to be roughly the same age as stars out our way.” (Our solar system is roughly halfway between the center of the Milky Way and its outer edge.) But they’re not. Stars in the nuclear region appear to be older than stars closer to us. And the reason why, Schlegel said, is probably because the black hole has blown the gas that could have been used to form new stars into the outer parts of the galaxy.

This kind of behavior, which astronomers call feedback, is the way our universe helps regulate the size of a black hole and of the galaxy itself. “Otherwise,” Schlegel said, a black hole that keeps eating and picking up new matter “could become large enough to engulf a galaxy.” So black holes not only consume new matter, but they also spit out and create new things.

“Double Bubble Trouble”

Sagittarius A*, the black hole at the center of the Milky Way, is relatively quiet, but it wasn’t always. In fact, it’s likely that millions of years ago “our” black hole blew two huge bubbles.

They extended tens of thousands of light-years above the disk-shaped Milky Way.

In 2009 astrophysicist Douglas Finkbeiner of Harvard University was looking for dark matter in the Milky Way. He and other scientists saw a mysterious microwave haze in the inner part of the galaxy. Perhaps, they thought, the haze was dark matter, pulled in toward the center of the galaxy by gravity. If dark matter particles collided with one another in the crowded core of the Milky Way, Finkbeiner thought, they would create high-energy charged particles and gamma rays.

Finkbeiner turned to recently released data from the Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope, a space observatory in low-Earth orbit. The NASA telescope, launched in 2008, scans the entire sky 24-7, 365 days a year, searching for the highest energy form of light: gamma rays. Finkbeiner and his colleagues found a lot of gamma rays in the inner part of the Milky Way galaxy, all right. As they analyzed the data, they began to see that the gamma rays were arranged in a big figure eight extending above and below the disk of the Milky Way. The figure eight looked like twin teardrop bubbles anchored one on top of the other at the galaxy’s core. According to computer models, dark matter wouldn’t do that. It would form a spherical halo. At first, Finkbeiner was disappointed. He told colleagues he had “double bubble trouble.”

Finkbeiner soon realized they hadn’t discovered dark matter. But they had stumbled onto something very interesting. The team named the gamma ray bubbles Fermi Bubbles, after the telescope they had used to find them. (The telescope itself is named after twentieth-century Italian American physicist Enrico Fermi. He helped build the world’s first nuclear reactor, among other accomplishments.)

What could the bubbles be? Scientists had discovered bubbles in other galaxies, especially galaxies with supermassive black holes one hundred or even one thousand times the mass of the black hole at the center of the Milky Way. Sagittarius A* is puny in comparison. It is a black hole of only four million solar masses. Up until then, it had the reputation among astronomers as a quiet wallflower among the louder, more boisterous black holes in the universe. With Finkbeiner’s discovery in 2009, it seems that Sagittarius A* may have seen some wilder times, perhaps as recently as the last one hundred thousand years.

“When stuff falls into that black hole, as you can imagine, it makes a big mess,” Finkbeiner told Scientific American. “One of the things that happens is very high-energy particles get ejected, and probably shock waves, and you can get jets of material coming off of the thing.”Those jets might well have formed the Fermi Bubbles.

Another possibility is that a burst of star births and deaths in the inner galaxy occurred, probably within the last ten million years. This flurry of activity could have propelled a great deal of radiation and matter outward, forming bubble-like structures.

It may be that the Fermi Bubbles were created by a combination of the two processes. Scientists have found evidence in other galaxies that when a black hole feeds, it leads to a burst of new star formation.

From end to end, the Fermi gamma ray bubbles discovered in 2009 extend 50,000 light-years, or roughly half of the Milky Way’s diameter. X-rays (blue) from ROentgen SATellite (ROSAT) observatory, a Germany-led mission in the 1990s, are the edges of the bubbles. The gamma rays (magenta) mapped by Fermi extend much farther.

Do Black Holes Sing?

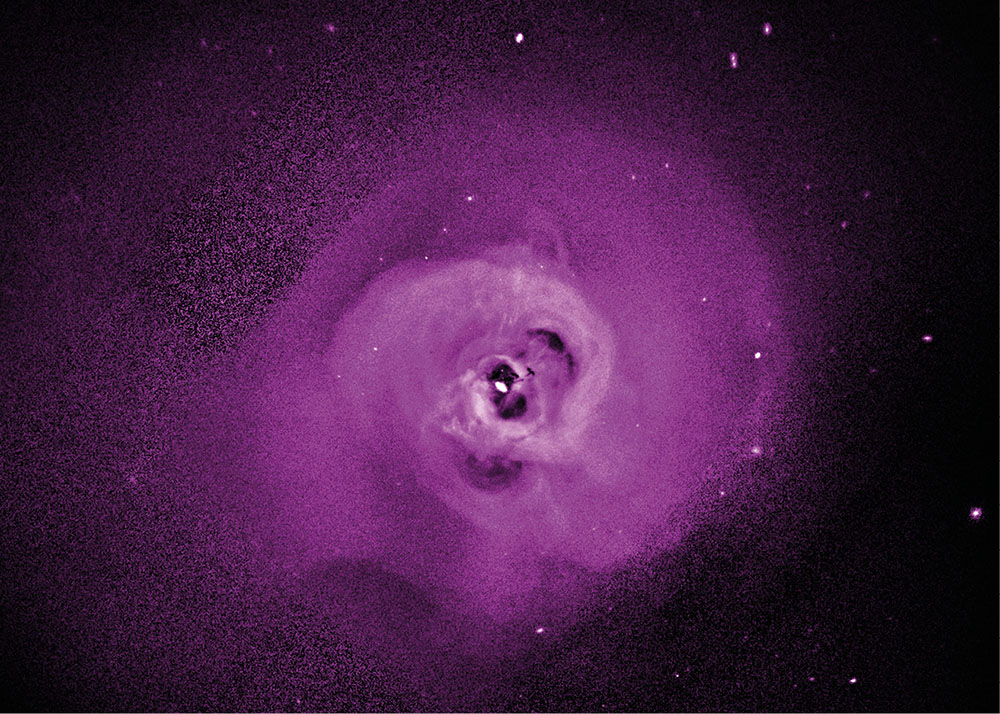

The Milky Way’s Fermi Bubbles are impressive. But in a galactic bubble-blowing contest, our galaxy falls far short. About 250 million light-years away is Perseus, a gigantic galaxy cluster. Like most galaxy clusters, it is anchored by a huge black hole at its center. The Perseus cluster contains one thousand times the mass of the Milky Way and stretches across 12 million light-years. Much of that mass is really hot, up to tens of millions of degrees Fahrenheit. It glows with X-ray frequency photons. In fact, it’s the brightest X-ray object in our neighborhood. It’s a great place to do X-ray astronomy.

Andrew Fabian, an astronomer at the Institute of Astronomy in Cambridge, England, used the Chandra observatory to make a detailed study of the Perseus cluster. He saw something incredible: two huge, bubble-shaped cavities, each about 50,000 light-years wide, extending away from the central supermassive black hole. Those cavities, bright sources of radio waves, are packed with high-energy particles and magnetic fields. The cavities pushed aside hotter, X-ray emitting gas, creating ripples in space—actual sound waves. The period of each wave, from one peak of the wave to another, is about ten million years. Chandra had recorded a snapshot of these slow-moving waves.

The Perseus black hole sound waves are a sort of song. They sing at a very low bass register, in a range far lower than we could ever hear—a million billion times lower, to be exact. The black hole sings just one note: a B flat that is fifty-seven octaves below middle C on a piano. For a visual animation of the sound waves generated by the Perseus cluster black hole, visit http://chandra.harvard.edu/photo/2003/perseus/animations.html.

The black hole seems to be doing much more than just entertaining nearby galaxies with its musical abilities. For years, astronomers have been puzzled about why so much hot gas is in the inner regions of the Perseus cluster. That gas should have cooled over the past ten billion years, forming trillions of stars. But it hasn’t. Why not?

Chandra observations suggest that the energy in the cavities is carried by the sound waves as they travel through the gas. That energy keeps the gas warm, preventing it from cooling. Every few million years, some gas starts to cool and condense, falling back in toward the black hole. The black hole feeds again, spitting out jets of matter once again, creating more bubbles and sound waves that send their rumbling energy outward into the gas. Those black hole bubbles seem to be serving as a thermostat for Perseus, keeping it at a steady hot temperature.

Galaxy clusters such as Perseus (above) are immersed in gas and are held together by gravity. Chandra observations of Perseus show that turbulence is preventing stars from forming there. The black hole at the center of this galaxy cluster pumps out huge amounts of energy through powerful jets of energetic particles. Chandra and other X-ray telescopes have detected giant cavities that the jets create in the hot cluster gas.

Perseus and the Milky Way aren’t the only galaxy participants in the cosmic bubble-blowing contest. Astrophysicists have found evidence for bubbles in 70 percent of all galaxy clusters in the universe. They have found evidence for sound waves traveling through the bubble surrounding the giant galaxy M87 in the Virgo cluster. That black hole sings even lower than the Perseus black hole, with notes as low as fifty-nine octaves below middle C. Many scientists believe that these bubbles are yet another indication that black holes shape entire galaxies.

The Green Valley of the Universe

In a 1970 song called “Woodstock,” singer Joni Mitchell famously sang about humans being made of stardust. American astronomer Carl Sagan elaborated in a somewhat more scientific, yet still poetic way. He said, “The nitrogen in our DNA, the calcium in our teeth, the iron in our blood, the carbon in our apple pies were made in the interiors of collapsing stars. We are made of star-stuff.”

Both Mitchell and Sagan are right. With the exception of hydrogen, which was made in the first few minutes after the big bang, the stuff (matter) we are made of comes out of dying stars that collapsed, went out in a blaze of supernova glory, and spewed new matter into the universe. We know that black holes, far from being simply greedy objects of destruction, can also regulate star formation and the structure of galaxies.

We can’t say for sure that life on Earth (and possibly elsewhere) would not exist without black holes. But it’s clear to scientists that the universe and its galaxies would be very different without at least some of them. They might not be very hospitable to life or at least to life as we know it.

For example, a galaxy anchored by a huge, voracious black hole would, over time, see little new star formation. And that means no carbon, oxygen, or other building blocks of life would be present. A galaxy with a slacker of a black hole, on the other hand, might create a lot of new stars. It might make massive stars that burn up in a hurry and explode, blasting away the atmosphere of any nearby planets. It wouldn’t be a very friendly place for life.

Caleb Scharf is an astrobiologist at Columbia University in New York City. He argues that the black hole at the center of the Milky Way galaxy was instrumental in creating a place suitable for life in the place and time in which life on Earth exists. The Milky Way, he said, “is in something of a sweet spot. It is neither one of those old-looking galaxies, nor one churning out lots of new stars. It is in between, in what astronomers call the green valley: it is still making some stars but not at a rate that is hazardous to the development of complex structures.”

Seeing the Unseeable

Long before Einstein published his general theory of relativity, John Michell proposed the existence of dark stars so dense that nothing, not even light, could escape their clutches. As if aware of the reaction he would get (what a preposterous idea!), he gave his paper a long, complex, and evasive title: “On the Means of Discovering the Distance, Magnitude, &c. of the Fixed Stars, in Consequence of the Diminution of the Velocity of Their Light, in Case Such a Diminution Should Be Found to Take Place in Any of Them, and Such Other Data Should be Procured from Observations, as Would Be Farther Necessary for That Purpose.”

We know that although Michell got the details wrong, he had the right idea. Imagine what he might think if he could jump into a wormhole and travel to our time. Surely he would be delighted to join Andrea Ghez atop Mauna Kea to watch the stars in their gravitational dance around Sagittarius A*. He would marvel at the gamma ray burst that announced the birth of a new black hole, the images of the burps and bubbles of black holes, and the music of gravitational waves. Michell, who designed and built his own telescopes, would be fascinated by the complexities of the many amazing telescopes—both optical and radio wave—that help us see the unseeable: the very edge of a black hole.

Equipped only with a homemade telescope and a top-notch brain, Michell came up with the rudimentary idea for black holes. In the two hundred-plus years since then, we have gained an incredible amount of knowledge about black holes. We can thank scientific advances in physics and astronomy, along with a technology boom that brought us increasingly sophisticated telescopes, detectors, and computers. And yet it seems clear that we could spend several more lifetimes studying black holes and working out what they can tell us about the way the universe works as a whole.

The current generation of telescopes and detectors, along with new ones in development, will be a source of scientifically rich data for years to come. Some of that data will probably be unexpected. It will probably lead to a deeper understanding of the laws of the universe. That’s how science progresses. Maybe you, the reader, will be a part of it.