Kazakhstan is a vast area of land in the heart of Eurasia, stretching nearly two thousand miles (3,000 km) from west to east, with a south–north range of more than a thousand miles (1,600 km). This huge territory is chiefly flat, covered in grass and shrubs, and is usually referred to as the Kazakh Steppe—a word of Russian derivation that can be defined as “terrain between forest and desert.” Much of the Kazakh Steppe is semi-desert, and it gradually turns into desert farther south. The country is bordered by Russia’s Ural Mountains in the northwest and a string of mighty mountain ranges along the south and east. The highest peak, Mount Khan Tengri (“Ruler of the Sky”), reaches nearly 23,000 feet (7,010 m). To the west lies the Caspian Sea, the largest lake on Earth, and the source of 90 percent of the world’s caviar.

As many visitors to Kazakhstan can confirm, the size of the country really does matter, and not just from the traveling point of view. It is central to understanding the history of this place and its people. Endless grassland reaching the skyline, without a soul to be seen for many miles, is the essence of everything Kazakh. The territory is a staggering 1 million square miles (2.7 million sq. km)—about the size of Western Europe—with a mere sixteen million inhabitants (2009 census), most of whom live in the larger cities. Away from the towns it is not unusual to drive for hours without meeting anyone. This is especially true for the least-populated central and southwestern areas of the country.

Kazakhstan is not as monotonous as it may sound, however. In fact, the country features an exceptional variety of landscapes that often contrast with one another. The steppe itself, primarily in the center of the country, can take you by surprise with its many fresh and saltwater lakes, which attract a great variety of waterfowl, and hilly areas that reach up to 4,900 feet (1500 m) in height. Southern Kazakhstan, which was once crossed by an important branch of the Silk Road, boasts the well-watered and forested Karatau Mountains (Black Mountains), an area rich in plant life and home to many rare birds.

In the north the steppe suddenly turns into a delightful and diverse region full of rivers, lakes, hills, and forests. These are some of the most photographed places in the country, famous among vacationers from other regions and neighboring Russia. However, the most stunning views are to be found in and around the high Tien Shan, the mountain range in the southeast, and the Altai Mountains in the northeast. These two huge massifs are the main attraction—apart from the Caspian oil and gas industry—for most visitors who come to Kazakhstan.

The largest cities in Kazakhstan are Almaty in the southeast (the busiest and most developed in infrastructure), the entrepreneurial and trading city of Shymkent in the south, and the industrial town of Karaganda in central Kazakhstan. No less important are the new showcase capital of Astana in the north and Atyrau in the west—home to a large expatriate community working in the oil sector.

Apart from its size, another distinctive feature of Kazakhstan is its distance from the sea in all directions: it is as landlocked as it is possible to be. The country’s only coastlines lie on closed seas—the Caspian and the Aral—which are, in fact, classified as lakes. This distance from the sea means that the country’s climate is generally described as acutely continental, with hot, dry summers, very cold winters, and low precipitation. In the north the summer temperatures average 68°F (20°C) and winter temperatures average -4°F (-20°C). Extremes are not unusual: 104°F (40°C) in summer, and winter temperatures of -40°F (-40°C) are far from rare, especially in the central steppe and in the northeast. The ground is covered by snow for nearly six months, from late October to early April. Winds, including the occasional buran—the strong snowy wind from the northeast—are typical.

The most beautiful mountainous spots are naively nicknamed “the Kazakh Switzerland” by the locals. This stems from a sense of pride at the scarce and precious beauties that nature has given this otherwise plain land. A legend from Burabay, in Kazakhstan’s north, reflects this. It tells how, when God created the Earth and its people, He began distributing mountains, seas, lakes, rivers, and fertile farmland among the different peoples. Everyone was happy except for the Kazakhs, who got nothing but endless, naked steppe. The steppe people asked the Creator to show them some mercy: can a whole nation survive in a land of bare steppe and desert? God looked inside his bag for the few treasures left, and threw all the remaining mountains, forests, streams, and lakes into the middle of the steppe. It turned out that those remnants were the best of all he had given—and that is how the most beautiful spot in the world was created. Burabay, its people say, is matched in beauty only by Switzerland.

In the south the climate is milder, with less contrast, though summers are hot. In Almaty, the average temperature in July and August is 79°F (26°C), and by Kazakhstan standards the winters here are not as harsh as in the north, though temperatures occasionally fall to -4°F (-20°C). However, the high humidity levels typical of the area of Almaty, sheltered by the Tien Shan range, ensure that you feel the cold down to your bones. Sensitivity toward both the humidity and the outside temperature are different for local people and western travelers, so it is not always helpful to assume that what the natives are wearing is an indication of the temperature.

There are some winter hazards common to the larger towns and cities that you should be aware of. One is ice on the sidewalks—broken bones and sprained ankles are not unusual, even for ice-savvy locals. A second is that icicles fall from multistory apartment blocks; injuries from these are rare, but they can potentially kill. A third hazard is the marble floors in some new buildings, which can be extremely slippery when wet.

Further south, in the region bordering Uzbekistan, winters are much milder, with temperatures averaging 30°F (-1°C).

Historically this land was populated by a Turkic people called the Kazakhs, meaning, in their language, free warriors or wanderers. They now comprise 63 percent of the country’s population of more than sixteen million. The remainder is a mixture of nationalities that migrated or were forced to move to Kazakhstan as the price of coexistence with Russia’s tsarist and Soviet regimes. The country’s Slavic population is dominated by Russians (24 percent of the total population, or about 3.8 million people) and includes Ukrainians (330,000 people), Belarusians (70,000), and Poles (34,000). Other major groups include ethnic Uzbeks (nearly half a million), Uighurs (225,000), Tatars (around 200,000), Germans (nearly 180,000), and Koreans (more than 100,000). Turks (Meskhetian), Kurds, Greeks, Jews, Gypsies, and some of the North and South Caucasus ethnic groups are less distinguishable yet have long been part of Kazakhstan’s history.

There is no formal or clear division of territories populated by one ethnic group or another, though southern parts are dominated by Turkic and Muslim groups (Kazakhs, Uzbeks, Uighurs, Chinese Muslim Dungans, Turks, and others) while the northern areas are largely settled by Slavic and German peoples. Culturally, however, there is no great distinction between the communities, due to the long shared history and common usage of the Russian language. In towns and cities the division is even less noticeable. Kazakhs are truly proud of the fact that since the breakup of the Soviet Union in 1991 there has been no noteworthy tension between the various nationality groups as in other parts of Central Asia. Some give credit to the traditional Kazakh values of tolerance and respect, and some to President Nazarbayev’s success in restraining any outbreaks of nationalism.

Economically, Kazakhstanis are considered to be far better off than their Central Asian neighbors. Officially in 2010 there were just over a million people (6.5 percent of the total population) living below the minimum subsistence level. This figure was nearly five times lower than that for 2000. Government reforms of pensions and social welfare provision have succeeded in their attempt to address poverty in a comprehensive way. The official 2010 unemployment rate was 5.8 percent, half that of 2000.

These figures, however, do not reflect the disparity among social groups or the contrast between rural and urban life. In 2010 the top 10 percent had official incomes that were nearly six times greater than the bottom 10 percent. The actual gap is believed to be much greater. As in the other parts of the former Soviet Union, “the rich” are a relatively new class that emerged in the 1990s. Most are businessmen, who hugely benefited from early market reforms and privatization, and senior civil servants with power and connections to large business.

The poorest groups are to be found in the countryside, where nearly half of Kazakhstan’s population lives. The rural poverty level is three times higher than that in towns and cities. You don’t need to travel far into the heart of Kazakhstan’s steppe to realize that the rural economy is in a submarginal state. The outskirts of the country’s brand new capital, Astana, are a grim reminder of the fact that Kazakhstan is still a country in transition, with a long way to go to achieve prosperity for all its people.

If, however, you are in the heart of one of the bigger cities, like Almaty, Astana, or Atyrau, you are most likely to encounter the well-educated and fairly prosperous middle class. These are people who have adapted well to recent economic changes. The younger they are, the more likely they are to be progressive thinkers, free from the Soviet legacy, and eager to get the most out of their lives.

The Kazakhs are the dominant ethnic group in the country, but this wasn’t always the case. Russia’s imperial and then Soviet policy led to sharp falls in the Kazakh population during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Many fled from new administrative changes and taxes imposed by the tsarist government, and many more died or were killed during the years of starvation and genocide of the 1930s Stalinist era. By 1939 there were fewer than 2.5 million Kazakhs left in the country. The picture changed after the breakup of the Soviet Union in 1991, when many of Kazakhstan’s Russians, Germans, and other ethnic groups that had either been forcibly settled in the country or had immigrated willingly in recent centuries chose to move back to their historic lands, while ethnic Kazakh communities living abroad started to settle back in Kazakhstan.

Kazakhs are generally perceived by fellow and neighboring nations as a very tolerant and open people who value two main things above all: peace, and their guests. Nomadic in the past, the Kazakhs have kept their friendliness and tradition of care toward travelers and newcomers, whether these visitors feel overwhelmed by the grasslands or just alone and awkward in an unfamiliar place.

In appearance, Kazakhs have Asian features, but there are distinctions between the browner southerners and the fairer-skinned northerly type; manners, language, and general conduct, however, really show the difference. Northern Kazakhs tend to regard the southerners as unintellectual and boastful, but respect their business sense; Southerners regard most of their northerly compatriots as being too slow in making decisions and generally boring. The most arrogant of all may be the inhabitants of Almaty—Kazakh or of any other nationality—who regard themselves as much more sophisticated because of the city’s historic capital status.

As mentioned above, many Kazakh families that had fled the country in the early twentieth century are returning to settle there. Since independence, nearly half a million ethnic Kazakhs have been repatriated to various parts of Kazakhstan. They are called oralmans (returnees), and they form a new and unique group in modern Kazakh society. They managed to preserve the Kazakh language and customs while living abroad, and are also bringing back aspects of other cultures. While much has been done to support them in their resettlement, their economic and social integration remains a significant challenge. They are one of the most vulnerable groups living in the country, lacking the means and the skills to prosper in their new environment. Some have successfully integrated, but many have chosen to return to the regions from which they originally came. It is sad that local Kazakhs who had previously demonstrated remarkable tolerance toward newcomers from various backgrounds in the earlier periods of history are showing a less welcoming attitude toward those returning.

Russians are the second-largest ethnic group living in the country. They dominated the population during the years of the Soviet Union, but millions migrated to Russia in fear of economic depression and discrimination after the Union’s breakup in 1991. Their fears did not materialize, and some of those who left in the early days of independence have since returned, but their status as citizens of independent Kazakhstan has changed.

Even though Russians still represent nearly a quarter of the country’s population, their current representation in the government is minimal in comparison to the earlier Soviet period, when Russians were not just an ethnic majority but were also the political and social elite. At independence the Kazakh language became the official “state” language, and although Russian was given special status, remaining the main language used in the public sector, the change was hard for the non-Kazakh population, especially those in middle age. During the Soviet era Russian was introduced as the official language, and the general policy was that knowing Kazakh was not necessary. As a result, many Kazakh families, especially those in the bigger cities, lost their knowledge of their language. Official use of Kazakh is still quite limited, and learning it is not yet the norm.

The younger generation of Russians has adapted well to living in the newly created state. Russians nowadays are the bedrock of the country’s urban middle class, owning small and medium-sized businesses in the manufacturing, trade, transport, communication, IT, and service sectors. However, wealthier Russian families try to send their children to study at Russian or Western European universities, preparing the ground for their smooth relocation in the future.

On an individual level there is a strongly sympathetic attitude, across all levels of society, toward Russians, who are regarded as honest, hardworking, and conscientious. Intermarriage between Russians and other nationality groups is still not common, but lifelong friendships are often made.

A small percentage of the population are neither Kazakh nor Russian. Most of these people were settled under a number of forced Soviet migration campaigns before and following the outbreak of the Second World War. Then, in the 1950s, many more immigrated willingly as part of the Virgin Lands campaign to cultivate cereals in the steppe. Some ethnic communities, such as the Uzbeks and the Dungans, had settled in Kazakhstan long before the establishment of the Soviet Union in 1917 for reasons of trade, business, and agriculture.

Most of these long-settled immigrants live in the southeast and south, the most fertile areas of the country, in distinct communities with their own subcultures and traditions. The main sources of income are agriculture—especially the growing of fruit and vegetables—and trade. The younger generation, notably Koreans and Azeris, are increasingly working in the bigger cities, in business, the financial sector, and banking.

Kazakhstan is a bilingual country. The dominant language used across all strata of society, especially in towns and cities, is still Russian, in which, according to the 2009 census, 85 percent of the population are fluent. Russian has special status as a language that can be used alongside Kazakh in government and public institutions.

Kazakh is the state or national language, and is promoted as a priority language to be used by government institutions and in Parliament. Its actual use by politicians is limited, however, due to the large number of Russian-speaking civil servants who do not know it well enough. It is widely used at an informal level, but less so during official meetings or in correspondence. However, it is the dominant language among the rural population, and about 60 percent of Kazakhstanis are fluent in Kazakh.

There is growing criticism over the constitutional status of Russian from some parts of the Kazakh community, who see it as the main obstacle to the development of Kazakh as the first language in the country. On the other hand, there are fears that stripping Russian of its official status may lead to another wave of emigration by Russian and other Slavic communities.

English is understood by about 15 percent of the population, with fewer than 8 percent conversing and writing fluently. Even on the streets of the biggest cities in Kazakhstan a visitor cannot expect to be understood in English.

Modern-day Kazakhs trace their direct racial ancestry to Turkic nomadic tribes who migrated to this region from what is now Mongolia and northern China. The early Turks, however, were not the first nomads to come to the vast steppe lands now known as Kazakhstan. Between 500 and 200 BCE, the land was home to the early nomadic warrior culture of the Saka (Scythian) tribes, who had migrated from the Black Sea coast to the foothills of the Altai Mountains, replacing earlier Stone and Bronze Age settlers.

The earliest Turkic-speaking peoples to arrive from the East were the Usuns, the Kangui, the Alans, and the Huns. They settled the Kazakh steppe lands from around 200 BCE to 500 CE. Around 550 CE the first feudal state, the Turkic Khaganate (empire), presided over by a khagan, or emperor, emerged. Later in the seventh or eighth centuries this empire was superseded by another Turkic tribe, the Tyurgesh. These were strong empires that prospered from the fabled Silk Road, a trading corridor that linked Europe to China and played a significant role in the commercial, cultural, and political development of the Central Asian steppes.

Despite its strengths, the region was unable to withstand attacks from the Arabs, who began their conquest of Central Asia under the banner of Islam in the mid-eighth century. They attacked the Tyurgesh Empire, eventually causing the Khaganate to collapse. Gradually Islam replaced Tengrism, Buddhism, and other religions that had hitherto been widespread. The Arab conquest also brought the Arabic script, which was to replace the Turkic alphabet previously in use.

Later the Arab Caliphate weakened and in 766 a new Khaganate was established in the far south of Kazakhstan by another nomadic Turkic tribe, the Karluks. In 940 their state was taken under the control of yet another semi-nomadic people, the Karakhanid tribe. The Karakhanids had by and large adopted Islam, and many took up a more settled way of life, cultivating fruit, vegetables, and cereals.

In the twelfth century the Khaganate fell to a wave of attacks from the east, and the Muslim Karakhanid tribe were displaced by the Karakitae, a Buddhist people from the territory that is now Mongolia. They created a new Central Asian state known as the Karakitay Empire.

Meanwhile the Oghuz Turkic tribes were settling in the steppes around the Aral Sea in Western Kazakhstan. Their state was soon absorbed by yet another powerful nomadic tribe, the Kypchak, known in the West as the Cumans. Through the next few centuries more nomadic tribes—the Kidans, Naimans, and Kerei—left their traces on the region’s culture and history.

THE GOLDEN AGE OF THE KARAKHANIDS

This was a period of overall stability and growth that benefited the development of southern cities such as Taraz and Yassy. (Around the fifteenth century Yassy was renamed as Turkestan, the name used by Russians to label the entire region.) It was also during the Karakhanid period that famous thinkers and writers lived and worked—men like the great philosopher Al-Farabi, who is known for his detailed study of philosophy, astronomy, music, and mathematics. The well-known scholar of Turkic philology Mahmud Kashgari also lived at this time. He wrote a three-volume dictionary of Turkic dialects that to this day is an important source on the history of Turkic folklore and literature. Another epic dating from this time is Kutadgu Bilig (“Blessed knowledge”). Written by the famous poet-philosopher Jusup Balasaguni, this book is regarded as one of the first literary monuments to the aesthetic thoughts of the Turkic people. The Sufi poet Hodja Ahmet Jassawi lived during the twelfth century in what today is southern Kazakhstan. His collection of poetic thoughts Divan-i Hikmet (“The Book of Wisdom”) is known throughout the Muslim world.

In 1218 the fearsome army of the Mongol leader Genghis Khan attacked Zhetisu, the area of southeast Kazakhstan known as “the Land of Seven Rivers” (Semirechye, in Russian), between the Tien Shan mountains and Balkhash Lake. The Mongol warriors then moved south to Bokhara in present-day Uzbekistan, Afghanistan, and India, and west as far as Hungary and Poland. Along the Syr Darya River alone more than thirty cities were completely destroyed.

These captured territories became part of the vast Mongol Empire, and were in due course shared among Genghis Khan’s four sons. The northern and western parts of modern Kazakhstan went to the eldest son, Juchi, and became known as the Golden Horde. (The word “horde,” derived from the Turkic ordu, means a tribal army encampment.) The second son, Chagatai, took Zhetisu, southwestern regions of present-day Kazakhstan, and the territories of Uzbekistan and Afghanistan. The share of the third son, Ogedei, included China and territories further east. The youngest son, Tolui, inherited the Mongol heartland.

The Golden Horde played the most important role in the later formation of the Kazakh homeland as a unified nation state. After years of war, prosperity came to the territory. Trade blossomed and many towns were rebuilt. Open intertribal war ceased. Due to their similar languages and culture the tribes coexisted peacefully, paving the way for the formation of tribal confederations, or zhuzes, the core of the Kazakh nation, that survive to this day.

Genghis Khan’s grandson, Batu, expanded the Golden Horde’s territory. He campaigned as far as Crimea on the Black Sea coast, and his domains eventually stretched from Irtysh in the east to Khorezm in the southwest, and to the Lower Volga in the west. His capital was Sarai-Batu, the present-day Russian town of Saratov.

This period came to an end in the late fourteenth century. Weakened by infighting and divisions among Genghiz Khan’s descendants, the Mongol Empire began to disintegrate. Emir Timur, or Tamerlane (c.1336–1405), who was associated by marriage with the house of Chagatai, became ruler of Mawarannahr (Transoxiana) and Central Asia, and carried out a number of devastating campaigns against the Golden Horde. A devout Muslim, Tamerlane built his own empire, with Samarkand as its capital. This included the far south of Kazakhstan.

The Golden Horde split into a number of smaller states, the largest of which were the Ak (White) Horde and the Kok (Blue) Horde. The Ak Horde was a significant political force, rich in territory and manpower, that strengthened its position under Urus Khan (khan, ruler) in the 1360s and ’70s. However, internal power struggles and the external threat posed by Tamerlane’s state led to the Ak Horde’s eventual collapse and the appearance in its place of a number of smaller states, including the Abulkhair Khanate. Its ruler, Abulkhair Khan (1412–68), was descended from Batu Khan’s brother, Shaiban. He extended his original territories to encompass the whole of modern-day north and northwest Kazakhstan. These events coincided with the rise of Mogulistan in southeast Kazakhstan, in what remained of the Kok Horde.

Abulkhair Khan was a zealous Muslim. Under his rule, the tribes and their leaders were required to observe Islamic laws and regulations. This and other policies made him unpopular among some of the sultans (members of the nobility), such as Zhanibek and Kerei, who in the mid-fifteenth century broke away from the Khanate for good, taking with them a number of tribes. These tribes were the first to be called Kazakhs.

In 1465–66, following the gradual concentration in Zhetisu of all those discontented with the policy of Abulkhair’s state, Zhanibek and Kerei proclaimed the Kazakh Khanate. Its influence grew rapidly, and flourished vigorously under Kasym Khan, an accomplished military leader and wise politician who was also known as “the gatherer-in of Kazakh lands.” Under his rule the Khanate ended up stretching from the Ural range to the Syr Darya River, and from the Caspian Sea to Zhetisu.

The state was divided into three regions—Senior, Middle and Junior—occupied by the main tribal confederations. The Senior Zhuz took the area between the Syr Darya and Zhetisu, the Middle Zhuz occupied central and northern Kazakhstan, and the Junior Zhuz settled on the banks of Aral Sea and in the Mangyshlak Peninsula, near the Caspian Sea.

In the seventeenth century the Khanate started suffering from severe internal instability. A continuing struggle for power in the Khanate and strong social polarization weakened the state in the face of new external threats. The main challenge was posed by the Zhungars, a Lamaist–Buddhist tribe in western China that had formed the Zhungarian Empire in 1635. In the late seventeenth century they started a grueling war for the pasturelands of Zhetisu and north Kazakhstan.

At first their increasing attacks led to a consolidation of forces within Kazakh society. Kazakh-wide gatherings (kurultay) took place on a regular basis and a united defense force was formed, but by 1723 the Zhungars had become a formidable military force that eventually crushed the Kazakh army. Many Kazakhs died on the battlefield, but many more succumbed to the famine and illness that afflicted the steppes as a result of the war. It was one of the darkest periods in Kazakh history, known as Ak Taban Shubyryndy (“the Years of Great Disaster”).

A later wave of resistance was led by batyrs (warlords) from the tribal aristocracy of the time. Their efforts brought a short-lived victory to the Kazakhs. The Zhungars came back in 1741, however, when Kazakh society was once again torn apart by tribal rivalry and power struggles.

Feeling vulnerable in the face of the militarily stronger and more numerous Zhungars, in 1734 the Junior Zhuz aristocracy under Abulkhair Khan (not to be confused with the fifteenth-century Abulkhair) concluded an agreement with Russia to accept its “protection” against external threats. The agreement left Abulkhair all powerful in matters other than external relations. In return for Russia’s protection, he promised to deploy his own forces to ensure the security of Russia’s trade caravans across his territory.

Later the other two zhuzes signed similar pacts with Russia to deny Abulkhair the possibility of seeking Russian support in any internal political struggle. However, they had underestimated the power these treaties gave to Russia. The documents inadvertently paved the way for Russia’s initially peaceful colonization of Kazakh territories. Russia chose to interpret the agreement as an annexation pact, and started expansion. Landless Russian peasants were sent to settle and farm the land; pasturelands were confiscated from locals; and a strict tax system was introduced. By the middle of the nineteenth century most Kazakh lands were under Russia’s direct control.

Naturally, revolts followed right across the steppe, but Russia’s grip was already too tight to be broken. More than a quarter of the population is believed to have died during the uprisings and famines that repeatedly occurred as a result of Russia’s claim to Kazakh territories. Many people, hoping to preserve their traditional way of life, fled to neighboring states.

In the summer of 1916 a powerful revolt broke out. Russia was preoccupied by the First World War, which exposed all the weaknesses of the Tsarist regime. The war caused poverty and hunger throughout the Russian Empire. In June 1916 an imperial decree was issued, and Kazakhs were conscripted into forced labor groups while their cattle and property were confiscated for military use. This appeared to be the last straw.

The uprising that became known as “The Great Revolt” swept across Central Asia. It was harshly suppressed at first, but erupted once more after the February Revolution of 1917. The formation of the first Kazakh political party, Alash, raised the stakes for the national liberation movement with its demand for full Kazakh independence. The first Kazakh Congress, held in October 1917, appointed a provisional autonomous people’s council of Kazakhs and gave it the task of drafting a democratic constitution with a system of government presided over by a president.

If the February Revolution gave the colonized nations of the Russian Empire some hope of self-determination and independence, their hopes were dashed when the Bolsheviks, a wing of the Marxist Social Democratic Party led by Vladimir Lenin, came to power in November. Civil war started. By the spring of 1918, Soviet power had been established in Kazakhstan through a combination of voluntary acceptance of the new principles and force of arms. On August 26, 1920, the Kazakh Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic was created as part of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR). Initially it comprised both Kazakh and Kyrgyz territories. In 1936 this was split into separate Kazakh and Kyrgyz republics, each of which was given enhanced status as union republics.

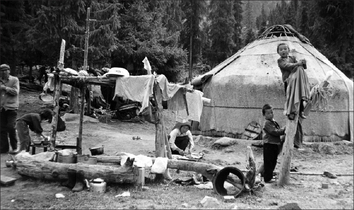

The leaders of the Alash party and their supporters were executed, and other intellectuals sent to labor camps or exiled. Kazakhs were prohibited from following their traditional way of life. Stalin’s wider “collectivization” program forced the previously nomadic population to settle in designated areas and to hand over their livestock to collective farms. Those opposing the policy were harshly punished, deported, or killed. Yet the hardest times were still ahead. Almost two million people died of starvation when famine swept the country as a result of collectivization, which also caused the disease and death of expropriated animals. Another million Kazakhs fled to neighboring China and Mongolia, with some moving further to Afghanistan, Iran, and Turkey. The Kazakhs lost nearly half of their population.

Regarded as suitably empty and remote, Kazakhstan began to be used as a place of exile for those considered real or potential threats to the Soviet system. In the years preceding the Second World War entire peoples were deported en masse from various areas of the USSR: Poles from Western Ukraine and Belarus, Volga Germans, Crimean Tatars, Kalmyks, Chechens, Ingush, Balkars, Karachai, and Meskhetians from Crimea and the northern Caucasus. Bulgarians, Greeks, and Armenians were among those forcibly relocated from the Black Sea coastal region. After the German army invaded Soviet territory these peoples were accused of collaborating with the German occupation forces. Needless to say, many of those deported starved or froze to death, either during their hard and long journeys to Kazakhstan or after arrival.

Furthermore, prison and labor camps were built in central and north Kazakhstan—vast and sparsely inhabited regions with no roads or sources of food, but rich in natural resources. Inmates were put to hard physical work, providing cheap labor for entire economic sectors of the Soviet Union, especially to help the war effort. In the mid-1950s, when Stalinism began to be denounced, virtually all the labor camps were closed down and the surviving inmates freed, yet many stayed on in Kazakhstan.

In the years that followed, more Russians, Ukrainians, and Belarusians arrived to take advantage of the new opportunities brought about by the extraction of coal, iron, uranium, oil, and other resources, and formed new industrial towns. Another 800,000 people migrated under the so-called Virgin Lands Campaign initiated by Moscow in the mid-1950s. Vast territories of steppe land in north Kazakhstan were irrigated and plowed to grow wheat. Water was taken from the Amu Darya (Oxus) and Syr Darya (Jaxartes) Rivers through newly built canals. The environmental downsides of the project were greatly underestimated. Only in the late 1980s did the catastrophic effects of the scheme on soil and landscape become apparent.

This was by no means the only environmental disaster of the period. The Semey oblast (region) in the northeast was the site of a forty-year experiment—exploding nuclear weapons in the atmosphere, at ground level, and underground. The Aral Sea, formerly one of the largest inland lakes on Earth, nearly died as most of its waters had drained away in another large-scale experiment that aimed to turn desert land into cotton and rice fields. And finally, the issue of the safe disposal of waste residue from decades of mining uranium, copper, and coal all across the industrial areas of the country has yet to be addressed.

Traditional Kazakh culture and language have also experienced their greatest challenges in the nation’s recent history. Becoming a minority in their own country, the Kazakhs had little opportunity to pursue their traditional way of life, while in the new Soviet world they were treated as second-class citizens without a history of their own and without a need to preserve their language. This doesn’t mean that the Kazakhs lost themselves as a nation, but the Soviet experience has had a substantial impact on what the nation is today.

Yet at the time, under the years of Soviet-style socialism, Kazakhstan made impressive leaps forward in the development of its economy, in its general and higher education, and in science. The country was transformed from a feudal state with a vast area of pasture for nomadic livestock breeders into a region with a large-scale industrial complex, a developed agriculture, and a livestock breeding system. By 1991—the moment of declaration of independence from the Union—Kazakhstan had become a modern, secular state with a strong extractive and industrial base, a developed economy, a well-equipped army, and good scientific potential.

In December 1986 a massive riot took place in Alma-Ata (now Almaty), the capital city at the time. Thousands of students protested the appointment of Gennady Kolbin—an official of Russian descent who had never lived or worked in Kazakhstan—as leader of the country’s Communist Party. This had nothing directly to do with Kazakhstan’s declaration of independence later in 1991, but it was indicative of a political shift that was spreading across the Soviet Union at that time.

The protest started in Alma-Ata on December 17, following the issue of a decree on Kolbin’s appointment the previous day. It spread to other big towns, and lasted for several days. Protesters were harshly suppressed. According to officials only two people died as a result of clashes between the police and protesters, and around a hundred people were detained, with some being sent to labor camps. However, the details surrounding the “December Events,” as they became known, remain locked in Moscow archives, giving rise to speculation about the actual numbers of dead and persecuted.

Following the protests in Almaty, similar unrest broke out in other parts of the Soviet Union. In the wake of a deepening economic and political crisis the central leadership in Moscow was seriously weakened, and unable to retain its control across the country’s fifteen republics. Finally, in February 1990, the Communist Party made a number of constitutional changes to allow for a more liberal political structure. These changes paved the way for a process sometimes described as a “sovereignty parade,” when local parliaments at republic level one after another started declaring their states sovereign within the Soviet Union.

Kazakhstan’s sovereignty was declared on October 25, 1990. The dissolution of the USSR, however, had already begun. The dissolution was complete by December 1991, despite attempts to preserve some form of union of sovereign states and even a coup d’état attempt by former KGB officials in Moscow.

Kazakhstan was the last to proclaim its political independence. Nursultan Nazarbayev, who had headed the republic’s Communist leadership since the 1980s, was elected president of the independent republic in January 1991. He adopted the Law on Independence on December 16, 1991, the anniversary of the Zheltoksan events of 1986 that had triggered Kazakhstan’s emergence as an independent nation.

The transition period following independence was not easy. Liberalization of the economic system started with the abolition of price controls in January 1992. This resulted in enormous inflation. In November 1993 a national currency, the tenge, was introduced, bringing the value of the Soviet rouble, in use at the time, to next to nothing. Industries came to a virtual standstill without ways to export their products, and workers were laid off with no means of survival. Savings vanished overnight. Remembering these times still brings a chill to Kazakh citizens today. The countryside was under threat of starvation, and a great influx of people into the towns and cities took crime levels to their highest ever.

Yet the latter years of this bumpy decade brought a wide variety of opportunities for those with natural business sense, and a spirit of entrepreneurship started to develop. Most found themselves in small trade and business, while some managed to create great fortunes from the early privatization of state enterprises. Foreign investment started to flow into the energy sector, and gradually brought the country’s economy to life. Local production of food, light industrial goods, and agriculture grew. The country eventually became self-supporting in food, which was considered a big step.

Twenty years on from independence, Kazakhstan has become a politically stable and economically prosperous country. It has built a reputation as the Central Asian pacesetter, thanks to its economic reforms and wise foreign policy. The country’s leadership is carefully trying to balance relations with bigger powers, such as the United States, Russia, China, and the European Union, each of which has a stake in the country’s economy.

However, bigger challenges lie ahead. The 2007 economic crisis showed that Kazakhstan’s economic prosperity is extremely vulnerable because of its dependence on raw materials. Diversifying the economy, fighting massive-scale corruption, addressing the disparity in wealth among the population, and moving toward a more liberal political system are only some of the tasks ahead. It is not clear whether Kazakhstan will be able to resolve all these issues, as they require fundamental changes to its internal policy. All that can be said at present is that the nation is well aware of them.

The 1995 Constitution provides for a democratic, secular state and a presidential system of rule. The president is head of state. He appoints the government with the approval of the lower house of parliament, the Majilis, and has influence on the composition of the parliament’s upper house, the Senate. In case of a vote of no confidence against the government, he can dissolve the Majilis. The president has the right to present bills and decrees and decides whether or not to hold referenda. In addition, he is the commander-in-chief of the armed forces, has the right to appoint and dismiss their leadership, and can proclaim a state of emergency in the country.

The president is elected by popular vote for a five-year term. The last elections were held in 2011 and were won by Nursultan Nazarbayev, who has been in power and practically unchallenged since independence from the Soviet Union in 1991. In May 2007, in accordance with the principles of the Organization for the Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE), the Constitution was amended to allow only two terms for a president. It also reduced the presidential term from seven to five years. Furthermore, these amendments allowed for greater government accountability to parliament. The changes are meant to initiate a gradual transition from a “presidential democracy” to a “presidential–parliamentary democracy.” The same amendments, however, made an exception for the current president, who can run for office any number of times and potentially stay in office indefinitely. In 2010, MPs granted Nursultan Nazarbayev the lifelong title of “leader of the nation.”

State governance is divided among the executive, legislative, and judicial branches. Parliament, we have seen, consists of the Senate (the upper house) and the Majilis (the lower house). Most senators are elected by assemblies of local representatives, while fifteen are appointed by the president. The Majilis, which functions as the main legislative body, has 107 MPs, with ninety-eight elected through party lists and nine provided by the Assembly of the People of Kazakhstan, a council of ethnic minorities. In the elections to the Majilis of 2012, Nursultan Nazarbayev’s Nur Otan party won the majority of seats (eighty-three seats out of the ninety-eight elected through party lists). The elections were yet again criticized by international observers, but were locally regarded as historical, as two other parties gained a foothold in parliament for the first time. The true value of parliament, however, remains questionable, as it is not regarded as an influential political institution, having no authority to appoint the government or to have a final say in setting the state budget.

The excessive concentration of power and authority in the hands of the president and his administration is said to be justified by the necessity to undertake swift economic reforms and preserve interethnic stability. This approach seems to be popular among the bulk of Kazakhstan’s population, despite criticism from Nursultan Nazarbayev’s political opponents—such as former senior civil servants and some businessmen, the most outspoken of whom have left the country to seek asylum in Western Europe after facing persecution in Kazakhstan. Press freedom is guaranteed by the Constitution, but private and opposition media are kept on a tight leash by the government’s use of unpopular media laws.

Administratively, the country is divided into fourteen administrative districts (oblasts). Almaty and Astana, the former and current capital cities, have their own administrative status and do not belong to any oblast. Each oblast is headed by a governor (akim) appointed by the president, and is subdivided into smaller districts (rayons). The rayons are governed by rayon akims and their offices (akimats). Since 2006 the majority of rayon akims have been elected by local representatives (maslikhats). Village akims are elected directly by the people.

Kazakhstan is the largest economy in Central Asia and the second-largest in the former Soviet Union, after Russia. Its economy demonstrated high growth rates over the last decade, reaching an average of 10 percent real GDP growth. This was interrupted by the global financial crisis in 2009, when growth plummeted to 1.2 percent. However, as a result of commodity prices strengthening on world markets and extensive governmental anti-crisis measures, Kazakhstan’s economy was relatively quick to recover, and grew by 7.3 percent in 2010.

The country’s economic growth is largely driven by extractive industries, which account for almost 20 percent of GDP. Kazakhstan produces up to 1.5 million barrels of oil daily, placing it eighteenth on the list of the world’s largest oil producers. According to the US Energy Information Administration, full development of its major oilfields could make Kazakhstan one of the world’s top five oil producers within the next decade. Although a significant oil exporter, Kazakhstan experiences regional and seasonal oil product shortages due to its low refining capacity and the difference between domestic and international oil prices. Apart from oil and gas, Kazakhstan contains Central Asia’s largest recoverable coal reserves, and is the second-largest coal producer in the former Soviet Union, after Russia. It is also endowed with rich reserves of chromite, lead, zinc, and uranium, as well as bauxite, copper, gold, iron ore, and manganese.

Despite its rich mineral resources, national manufacturing comprises only 11 percent of GDP and is characterized by low levels of productivity, lack of innovation, and outdated technology. Other significant sectors of the economy are wholesale and retail trade (13 percent of GDP), transportation (8 percent), construction (7.7 percent), and agriculture (4.5 percent). The construction sector’s vulnerability was demonstrated in 2008–09, when a shortage of capital investment from abroad led to a credit crunch and stagnation in construction.

While acknowledging the risk of dependence on oil and extractive industries, Kazakhstan aspires to become a modern, diversified economy with a high value-added and high-tech component. To this end it has embarked upon an ambitious diversification program that aims to boost the country’s potential with industrial innovation. By 2015 Kazakhstan aspires to join the fifty most competitive nations expanding non-raw-material exports and increasing the contribution of manufacturing to GDP. However, despite these well-defined objectives, progress lags behind the targets and independent economists are skeptical about the program, citing such factors as high levels of corruption and nepotism, and governmental interference into market forces.

Integration into the global economy is also seen as an important driver of economic development. Kazakhstan is at the final stage of negotiations to join the World Trade Organization (WTO). In addition, on January 1, 2010, together with Russia and Belarus, Kazakhstan formed a trilateral Customs Union and is now firmly moving toward a Eurasian Common Economic Space that will enable free movement of goods, services, capital, and labor among the three countries. The planned accession to the WTO and formation of the Customs Union have been subjects of heated debate among local producers and businesses, who continuously express concern about the low competitiveness of local manufacturing in both global and regional markets.

Most of Kazakhstan’s environmental problems are a legacy of the former Soviet system. Its territory suffered from extensive military testing and space launches, for example. The northeastern region of Semey was most severely despoiled, being the place where the Semipalatinsk nuclear test site operated for forty years. Nowadays the central part of Kazakhstan, home to the world’s largest space launch facility, Baikonur, is under constant environmental threat from falling fragments of rockets and highly toxic fuel.

Another inherited disaster is the massive erosion of the soil and the impoverishment of natural landscapes that resulted from the forcibly imposed Virgin Lands campaign of the 1950s. Under the campaign the Soviet government undertook to cultivate wheat on a massive scale by irrigating the steppes of northern and central Kazakhstan. After fifty years of over-intensive cultivation, the living steppe has been transformed into dead semi-desert. Some sources estimate that the country has lost 1.2 billion tons of topsoil. Furthermore, the excessive agricultural development across the country resulted in universal degradation of soil. More than 60 percent of the country’s territory is now exposed to desertification.

The Aral Sea is yet another distressing reminder of the manmade disasters of the Soviet period. Once the world’s fourth-largest inland lake, with a uniquely rich ecosystem, the Aral has now broken up into a number of lakes, having lost 80–90 percent of its water as a result of poorly planned irrigation systems. The southern part, bordering Uzbekistan, is considered to be a lost cause, but the northeast corner (Little Aral) has started to fill up with water again due to the efforts of the Kazakhstan authorities and support from international aid agencies. There are serious fears, however, that the tragedy could be repeated at the lake of Balkhash, which is rich in fish and other wildlife. Excessive industrial use of water from the Ili River, which runs into Balkhash, and emissions from the Balkhash metallurgical complex are the main reasons for anxiety.

As a whole, the rapid expansion of extracting and manufacturing industries has been most detrimental to Kazakhstan’s environment. Among the most harmful are lead-zinc production in Oskemen in the northeast, lead-phosphate production in Shymkent and phosphate production in Taraz, both in the south, and the chrome enterprises in Aktobe in the northwest.

A new environmental threat now causing concern is oil pollution in the Caspian Sea, where extensive exploration and extracting activities have affected both the temperature of the seawater and the humidity of the atmosphere, and have led to the extinction of rare fish and other live organisms. The destructive effect of oil pollution is especially evident among the birds that live on these waters, and stocks of sturgeon are falling.

Despite numerous environmental programs developed by the large extractive companies and the government under the pressure of international organizations and civil society, it seems that environmental protection and conservation are still not top priorities. Public ignorance, underestimated risks, indifference, and the public bodies’ inability to influence state policies and business practices all contribute to the lack of progress.