Properties: Research, Detail, and Crafts

Unlike most things in the theater, prop work is most often done by individuals. Carpenters, electricians, riggers—all these people tend to work in crews, but props are most often created by people working solo. Props are chosen (or invented) by the scenic designer or prop designer, working alone; realized by a craftsperson or located by a researcher, working alone; placed by a single prop person backstage; and, if they are handled during the show, tend to be handled by a single actor.

Prop work is composed of three distinct types of work and, as such, is populated by three fairly distinct types of people. It’s worth it to take the time to recognize which type your prop person is. Of course, many prop people are a combination of more than one type, and every now and then, you meet someone who embodies all three (hire her!), so take these definitions loosely. They are offered here because of the intimate, one-on-one nature of prop work, as well as the necessity of getting to know the people in this department on a personal basis. The following are not individual job titles, just some general personality types that you will likely encounter.

The Artisan

Some people have a gift for creation and imitation. These people take great joy in mastering long lists of materials and techniques while devising new and previously unheard-of ways to construct anything the designer can invent. This process is not so much mental struggle as mental exercise to them, and they generally have flexible minds: able to see peas as pearls, pop-tops as chain mail, and washing machine agitators as royal crowns. They are problem solvers, more often discouraged by bureaucratic obstacles than overwhelmed by an unsolved design problem. They can make treasures out of the junk most folks throw in a dumpster. And the best ones can do it by Thursday. These people are often called “crafts” people, and they are best called in to construct particular pieces, such as fantasy props or furniture.

Look in the dictionary under the words “mind-numbing detail” and you will find the reference: “see also: props.” There are shows in the world without a lot of props, but don’t hold your breath waiting for one to come along. Someone has to coordinate the sheer numbers of props, particularly in shows with complicating factors such as real food, animals, multiple scene changes, or trick props that have to light up, explode, break, or fire on cue. Fortunately, there are people in the world who take joy in making sense of this kind of detail. These people live with lists on legal pads and ballpoint pens hung around their necks. They will not rest until their clipboard has a long list of check marks and completed quests. The telephone is a shrine to them. They know how to combine errands to save time. They can read a map. These people are invaluable in heavy prop shows and low-budget theaters that must do a lot of borrowing and begging.

The Researcher

All propmasters inevitably collect a long list of antiques stores, junk shops, and bargain stores where they find many of the pieces that they need for shows. A true researcher goes even further, mentally (or physically) cataloging thousands of pieces all over town, taking joy in searching out the perfectly odd prop. For her, prop work is a quest—a journey into a wilderness of goofy, unexpected, hidden treasures. She is inventive with her sources and will call places you and I would never think of. I once watched Jolene Obertin, the prop coordinator at Seattle Rep and a true researcher, find a ten-inch-high scale model of the Statue of Liberty in two minutes flat without leaving her desk. She got it on her second phone call—to the gift shop at (where else?) the Statue of Liberty in New York City. They ship, for a small fee.

So, now that we’ve met the prop staff, let’s get down to business.

Making the Prop List: When to Buy, Borrow, or Build

Prop Genesis, v. 1

In the beginning, there was the Script. And the Script listed all the props that were necessary for the action to take place, as well as a few more that were mentioned because they were used in the original New York production.

Prop Genesis, v. 2

And the Director said, “Let there be a Concept,” and he saw that many props were needed to realize his Vision, so he turned to the Stage Manager and said: “Can we get a stuffed alligator to hang up there?”

Prop Genesis, v. 3

And the Producer said, “Let there be a Design,” and the Designer called for many more props, either by sketching them in great detail or by writing little notes in the margins like “fill shelves with books and other stuff.”

Prop Genesis, v. 4

And the Producer hired the Actors, who realized as rehearsal progressed that they needed notebooks and pens, funny hats and noses, and cigarettes with long, elegant filters or they, too, would not realize their Vision.

Prop Genesis, v. 5

And the Propmaster saw that order needed to be laid upon the land, and so she made the prop list, which contained every prop that she had heard of in her travels. And she was sore afraid—for the list was long and complicated. Yet she took heart, for Opening Night was six weeks away and she had no time to Freak Out.

And so was born the prop list. And it was long.

Everything begins with the prop list. It should contain every prop that will finally end up on stage, and it should be compiled as early in the production process as possible. Like everybody else, prop people like to know what is expected of them early in the game.

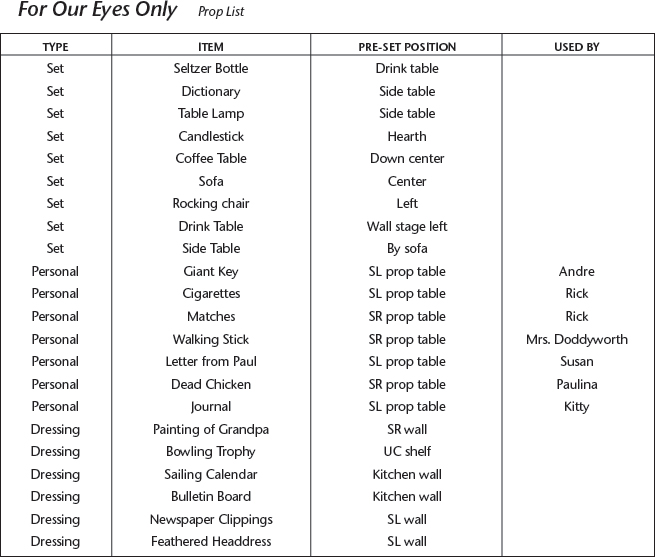

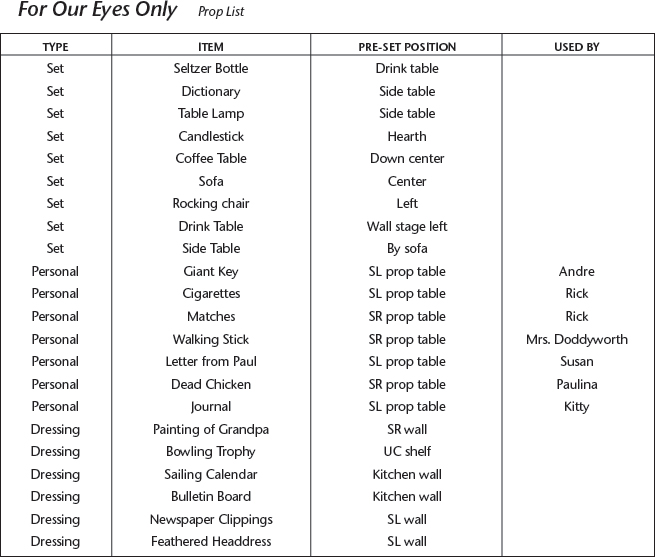

Fig. 49. A sample prop list

The list should identify a prop as one of three categories: set props, personal props, and set dressing.

Set props are preset on the stage and generally left there. They are often handled, sat on, picked up, dialed, or passed around by actors in the course of the action. Set props include furniture, lamps, appliances, rugs, phones, and so on. They tend to take up most of the prop people’s time because (a) they are large enough to be clearly seen by the audience, (b) they often are specific to the story, and (c) they are used by actors.

Personal props, since they are also employed by the actors, are also high on the list of priorities. They rank second only because they are smaller and, relatively speaking, require a little less effort since their appearance is less noticeable to the audience. Personal props are assigned to a particular actor and preset on the prop table. They include things like pens, cigarettes, documents, money, and anything else handheld that is assigned to a particular actor. Want to piss off the prop people? Forget to put your props back on the table when you exit the stage, forcing the propmaster to come find you in the dressing room. Want to permanently piss off the prop people? Play with props that aren’t yours.

Set dressing is the lowest priority since it doesn’t affect the action. Set dressing includes things like pictures on the wall, knickknacks to fill up shelves, draperies, and anything else that fills up empty space and helps to communicate the nature of the space to the audience. In some situations, set dressing doesn’t even appear on the prop list, since it consists of whatever the designer and propmaster can find in the prop room. Nevertheless, efforts should be made to get these props on the list, because it will make it easier for the prop people to know what you want. The list will also help you track where the props came from and where to return them after the show.

Once the list is under way, the next step is to divide the props into the same categories as costumes: build, buy, pull, and borrow. This is where the detailers come in. The decision about where to get the prop depends on several factors.

• Money is, of course, the basis of all such decisions. A propmaster balances the money available in his budget against the money needed to buy a prop. If the budget will support it, buying a prop is the least labor-intensive way to get a prop.

• Available labor, which is another way of talking about money, will determine what can be built. This is where the artisans come in. Prop building requires a number of different skills including carpentry, sewing, foam carving, plastic molding, and more. Prop artisans are unusual craftspeople, and prop-building technique is unlike anything else. A household furniture builder, for example, will be surprised at how his creations are treated onstage and will hold his head in dismay as the joints come loose.

• Time, the third leg of the logistics stool, determines what you have time to make.

• Availability means “can I find it?” With period shows, this is a major factor. Sixteenth-century furniture doesn’t grow on street corners. Nor do specialty props, that is, props that sprang from the mind of a sadistic playwright. The show Ten Little Indians, for example, requires a set of ten porcelain Indians, seven of which get destroyed every night. No, no, thank you, Dame Agatha Christie.

So …

• Buying a prop saves time and labor, but you are dependent on availability and budget.

• Building a prop is usually cheaper than buying and solves the availability problem, but you need the necessary talent.

• Borrowing saves time and money, but it is completely dependent on availability (and the good will of the lender).

• Pulling a prop from stock is always the best option, but, if you don’t have it, you can’t pull it.

Furniture: Why the Stage Isn’t Like Real Life

There is one really unfortunate thing about stage props. Many of them bear a striking resemblance to things we have in our own homes, like tables, chairs, and sofas. It isn’t unusual, therefore, particularly in low-budget theater, for people to raid their own homes and the homes of others to find furniture for their shows. Go visit the home of any community theater luminary, and he will probably have a story for every piece in his living room: “Oh, yes, that’s the sofa from The Boy Friend, and that chest was used in Man of La Mancha, and the desk is from Harvey,” and on and on.

Most theaters can’t afford to buy furniture for every production, and it is simply impossible to have every kind of furniture that you need in stock. Hence, theaters borrow all the time. This is not a bad thing, but you should proceed with caution. Let me illustrate with two stories.

Some years ago, I did a production of The Music Man, the musical comedy about everybody’s favorite con man, Harold Hill. In the second act, while trying to seduce the town librarian, Hill sings “Marian, the Librarian” to her in the middle of the town library, which is full of chairs and tables. The song becomes a raucous dance number, all the more fun because it is going on in the normally sedate library, with Marian frantically trying to shush everyone back into silence. Fun stuff. At least it was fun until the choreographer decided to introduce a little Donald O’Connor choreography with the chairs. You may be familiar with O’Connor’s very physical dance routines, particularly the ones involving furniture. Our choreographer created a very exciting sequence that had all the dancers leaping onto a chair, stepping up onto the back of the chair, and then riding it down backwards until the chair landed on its back on the floor. Really fun.

And really dangerous. The chairs and tables had been borrowed from a local high school, and they were built entirely of wood. There was no way that they were going to put up with that kind of strain, and, sure enough, after a couple of weeks of rehearsal, most of them were broken. We were lucky not to have broken dancers as well. The number was re-staged, and a substantial chunk of the props budget went to buying new chairs for the school.

Household furniture is made to be sat on, slept on, worked on, and eaten on, but it is not made to be jumped on, danced on, stomped on, or marched on. It is also not made to be thrown, dropped, kicked, or used as a weapon in a fight. This doesn’t mean that you can’t do all these things (and more) with household furniture; it just means that it wasn’t designed for it.

Even if your play is devoid of violence or dancing, you will find that stage furniture goes through more punishment than the furniture in your home. For one thing, it gets moved around all the time. If you’re anything like me, your living room furniture hasn’t moved since the last time your mother came to visit and she ran a vacuum under it. Theatrical furniture gets moved all the time, sometimes several times a day, if you have scene changes. It gets thrown up onto storage shelves, dropped in the wings, and loaded into pickup trucks. All this moving is very hard on the joints that hold furniture together, and they will weaken and come apart much more rapidly than furniture at home. Furthermore, actors are much more concerned with portraying a character on stage than they are with sitting down properly. They will collapse harder into a stage chair than the one at home, and, no matter what their stage mother tells them, they will invariably lean back. Bottom line? The stage is not like life, and prop furniture feels the pain.

What to do? Well, sometimes you have to build furniture especially for this kind of punishment. Those chairs that Donald O’Connor is flinging around in his dance routines were specially built out of steel to stand up to his needs. Sometimes, rather than building a piece from scratch, you need only fortify regular furniture with extra steel or wire. One common trick is to add an “X” of tightly wound wire between the four legs of a chair.

Fig. 50. A chair strengthened with wire

Step one: talk to your propmaster. Tell her which pieces of furniture will receive special abuse and how often. Then listen to the propmaster. If she tells you that a chair is not strong enough for what you have in mind, don’t dismiss her input as alarmist. It might save you a broken chair (or a broken arm) later.

Besides keeping your performers healthy, it is also important to keep relationships with lenders healthy. Second story: when I did The Miracle Worker a few years back, I brought in my own dining room table for the famous breakfast scene. In this scene, the young Helen Keller falls into a rage because her teacher, Annie Sullivan, forces her to eat her breakfast with a spoon instead of with her customary fingers. In response, she hurls her spoon violently down on the table. Annie puts it back, Helen throws it down. They repeat this pattern over and over until Helen finally gives in.

I delivered the table to rehearsal and didn’t check back with the stage manager for a week or so. When we went to pick up the table for the first tech rehearsal, I was amazed to find the top of the table deeply gouged from the repeated spoon attacks. One-quarter of the table (the quarter that the actress could reach from where she sat) was completely stripped of its finish. After just a few rehearsals, the action of the scene had laid waste to the table. Because it was my own table, the only person I had to worry about was me, but if the table had come from another source, I would have had a real problem. Instead, I had another one of those “Look, there are the gouges that Helen Keller put on my table” stories that abound at theater people’s dinner parties. Had the table been borrowed from a member of the theater’s board of directors, it might have been a source of anguish, especially since a felt pad would have prevented the entire thing.

The moral? Be aware that theatrical action takes a higher toll on furniture, and, whenever possible, take steps to prevent the damage.

Weapons: Safety and Proper Handling

As with doors and windows, the first question to ask about a gun is whether it needs to be practical. In other words, does it need to fire? If not, then by all means, don’t use a real gun onstage. The only exception to this is in an extremely intimate theater where the audience can clearly see that a prop gun is being used. Other than that, there is no compelling reason to use a real gun on stage if the gun isn’t fired. Even if it is fired, a starter pistol that can fire only blanks should be used, if possible.

The first problem with guns and, in fact, with any weapon at all is theft. I tell my students over and over, “Weapons walk.” This has been demonstrated over and over. There is a fascination with weapons, both among actors and technicians. Somehow, when you put a weapon in someone’s hands, it brings out a primal hunter-killer personality, and he won’t want to give that violent talisman back. Lured by television and movie images of weapons, people get a charge out of carrying and using them. It is always amazing to me how, whenever I hand a gun to somebody—anybody—they immediately point it at somebody. The presence of a weapon alters people’s personalities and impedes their logical thinking. Hence, when there are weapons around backstage, if you don’t go to absurd lengths to protect them, they will walk away. They will, they will, they will. Trust me.

If you have weapons in a show, whether they are practical or not, there should be one person (usually a prop person or a stage manager) who looks after them personally. If possible, the location of their storage place should not be common knowledge, and they should be kept under lock and key. If a gun must fire, have the person responsible load it at the last possible moment and hand it to the actor just before the actor goes on stage. When the actor comes off, the same person should be there to receive and unload the gun. If you are using a real gun, be aware that, in some states, the person handling the gun may need a firearm license.

Safety Alert! All guns, even blank guns, are dangerous. As I am writing this, we are mourning the death of Jason Lee, a young actor tragically killed on a movie set by a gun that was firing blanks. This accident was highly unusual, but it still reminds us of the extreme care that must be taken with all firearms. Even though blank pistols do not have a bullet in them, they still emit a blast that can be harmful or even deadly. They often throw out wadding or other materials with deadly force. Never fire a blank gun when it is pressed against a person’s head or body. Never fire a gun when it is pointed at a person’s face. Back off. Aim lower, or to the side. The audience will be startled by the gun going off anyway, and they will never know the difference.

One other note about guns: it is not unusual for a blank cartridge to misfire or not fire at all. Therefore, when you load a blank gun, load all the chambers, just in case. Actors, take note. If you pull the trigger and the gun doesn’t fire, pull the trigger again, and again. Nine times out of ten, you will get the bang on the second or third try. Also, if you are handling a gun onstage, learn the location and operation of any safety switch. Otherwise, you may unwittingly flip that switch and be left with an inoperative gun, and there aren’t many ad-libs that will get you out of that one.

There is one legendary story about an actor whose gun wouldn’t fire, even after repeatedly pulling the trigger. After looking around helplessly for a knife, a rope, anything lethal he could use to cover the moment, he finally cried out, “Aha! I will kill you with my poison ring!”

Of course, any blades you use should be blunted. If the blade is being handled so close to the audience that they can see that it is blunt, then you are handling the blade too close to the audience. Any blocking that requires a blade to be thrown or kicked across the stage should be rehearsed fanatically. If you do have a weapon being thrown or kicked, you should block the moment in such a way that, if the actor misses, the weapon will fall harmlessly against the scenery or backstage. Never stage a fight with weapons out in the audience. All stage fights should be rehearsed before every performance.

During a production of Henry IV, Part 1, at Brown University, the actor playing Hotspur caught the tip of a sword across his forehead and began to bleed profusely. He finished the fight, died dramatically, and was dragged offstage. As it happened, there was a critic in the audience who gave us this review: “The fights were admirably staged, although the bloody death of Hotspur felt overdone.”

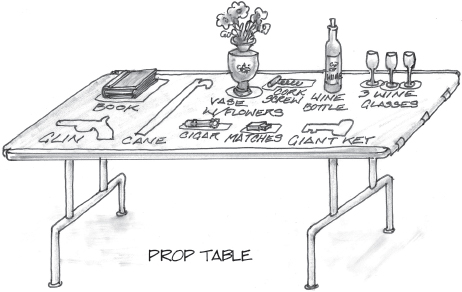

Handling Props during the Show: Prop Tables

It is essential to have good prop tables. Find a big table to put by each entrance to the set. Cover the table with a large sheet of white paper (usually called “butcher paper” and available from an art store), and, using the real props, draw their outlines on the table with magic marker. That way, you can tell at a glance whether you have everything. Props should be preset on the table by whichever entrance they come in, and actors should be trained to pick them up just before they enter the scene and drop them off as they leave. Props should never be taken to the dressing room, with the exception of costume props, like watches and jewelry (they’re usually handled by the costume people anyway). Actors get attached to props and they sometimes want to keep those props with them, but this practice inevitably results in the actor suddenly realizing, seconds before his entrance, that the critical walking stick is hanging on the back of his dressing room chair. I have seen enough mad dashes to the dressing room by frantic stage managers to state this without reservation: leave the props on the prop table. I’ve said it before, and I’ll say it again: actors aren’t stupid, they just have a lot to think about.

Fig. 51. A prop table