A cigarette is the perfect type of a perfect pleasure. It is exquisite, and it leaves one unsatisfied. What more can one want?

OSCAR WILDE, THE PICTURE OF DORIAN GRAY, 1891

Let us provide the exquisiteness, and hope that they, our consumers, continue to remain unsatisfied. All we would want then is a larger bag to carry the money to the bank.

COLIN C. GREIG, STRUCTURED CREATIVITY GROUP, BRITISH AMERICAN TOBACCO, COMMENTING ON WILDE’S RHAPSODY, 1984

It has always struck me as odd when people are shocked to learn that the tobacco industry has “manipulated” nicotine chemistry. What should we expect? Nicotine manipulation is not even necessarily a bad thing: if you’re going to smoke, you’d probably just as soon have your nicotine manipulated as left to chance. Whiskey makers know—and can control—how much alcohol will end up in their product, and drug makers of course calibrate dosages quite precisely. Heroin users die because their doses are unregulated, uncontrolled.

The presumption behind the shock seems to be that tobacco should be as “natural” as possible. And the industry itself has cultivated this image of the cigarette as a folksy, down-home product that is honest, simple, and unadulterated (albeit now “controversial” and “risky”). But tobacco has never been a natural phenomenon, not as used by humans at any rate. Like olives or ayahuasca, tobacco leaves have to be painstakingly cured and processed prior to consumption. For this alone we cannot condemn the cigarette. The real indignity stems from precisely how and why cigarette makers have manipulated nicotine chemistry—which has been dishonest but also deadly. Cigarettes were designed to appear to be safe, when the manufacturers already knew they were not. We’ve encountered the nested frauds of filtration and ventilation, made possible by a crafty exploitation of compensation. But it’s also important to realize that the chemistry of tobacco has been manipulated in a deceptive manner, with the goal of keeping smokers hooked. Smokers have been encouraged to switch to brands promising ever lower yields, without being told that the nicotine in those brands has been juiced up chemically to increase its potency. Think of cajoling an alcoholic, “Here, have some vodka, we’ve taken out some of the alcohol!”—while secretly increasing the potency of those molecules that remain. Nicotine freebasing is comparable, and consequential. This simple chemical trick helped propel Marlboro from obscurity to the world’s most popular cigarette—and still today helps keep smokers smoking.

Nicotine, as Claude Teague at Reynolds used to say, is the sine qua non of smoking.1 People smoke to obtain this simple alkaloid, which stimulates the brain and eventually leaves the hard mark of addiction. Hints of this beguiling twist were recognized prior even to the discovery of the nicotine molecule: Christopher Columbus is said to have observed with regard to his sailors taking up the pipe, “It was not within their power to refrain from indulging in the habit,” and King James I in his notorious Counter-Blaste to Tobacco worried that “he that taketh tobacco cannot leave it, it doth bewitch.” The great French traveler Jean-Baptiste Tavernier wrote from Persia in 1640: “Men and women are so addicted that to take tobacco from them is to take their lives.” Mark Twain is famous for his quip that smoking was easy to quit; indeed he had done so many times.

It was not until the twentieth century, however, that the mechanisms by which nicotine railroads the brain came to be deciphered. The British physiologist John Langley was a pioneer in this realm, using nicotine to map the cholinergic peripheral nervous system. In a series of experiments using curare, nicotine, and other psychoactive chemicals, Langley and his collaborators postulated the existence of “receptor” sites in cells that would receive and transmit the chemical instructions involved in all neurotransmission (indeed we still talk today about “nicotinic cholinergic receptors” throughout the body). Lennox M. Johnston of Glasgow, Scotland, in a widely read article in Lancet later showed that people injected with nicotine eventually develop a tolerance, and then a dependence, and that people develop cravings when the injections stop. Johnston, much of whose work was “suppressed by smoking medical editors,” proposed that tobacco use was “essentially a means of administering nicotine, just as smoking opium is a means of administering morphine.”2

Cigarette makers would eventually come to realize that the impact of nicotine could be manipulated, even while keeping its quantity in any given cigarette fixed. In the 1940s, for example, Lorillard scientists at the company’s Middletown, Ohio, branch explored the possibility of adding urea and other alkaline agents to cigarette paper to raise the pH of cigarette smoke. A letter of April 11, 1946, from the company’s chief chemist to the head of its Committee on Manufacture noted that a number of different buffers and bases had been added, causing the production of “a volatile base when the cigarette is burned.” Sodium bicarbonate, soda ash, caustic soda, and caustic potash all were explored for this purpose, as were compounds such as ammonium phosphate, triethanolamine, and hexamethylene-tetramine. Ammonia was selected as “about the only material that we know of which is easily volatile”; the problem was therefore to find “a compound which contains bound ammonia that will be liberated by heat of combustion.”3

Here are some of the early glimmers of the “freebasing” revolution that would rock the industry in the 1960s and 1970s, propelling Marlboro to the top of the cigarette charts. There was not yet any point, however—not in the 1940s or 1950s—to boost the potency of nicotine. Tobacco chemists were still looking mainly for ways to make smoke “milder,” and acid-base manipulations were done mainly to reduce harshness from corrosive acids or (more often) bases. There was not yet much of a demand for low-nicotine products, and manufacturers felt no urgency to augment nicotine’s potency. Tobacco researchers knew that free nicotine could be released by increasing pH, and even knew that free nicotine had a greater physiologic impact.4 But that was more or less a curiosity, since there was not yet any push to lower yields.

With increasing publicity of the cancer hazard, however, cigarette makers began trying to lower tar and nicotine deliveries and to better understand how nicotine works in the body. Countless schemes were devised to lower nicotine levels—which wasn’t terribly hard from a manufacturing point of view. The alkaloid is water-soluble, so a simple soaking will remove most of it from the leaf. (That is one reason hand harvesters sometimes suffer from green tobacco sickness: tobacco leaves wet from the morning dew can transfer nicotine to the skin, causing poisoning or even death for long-term handlers. Contact with sweat on the skin can have a similar effect.) Breeding techniques were also developed to produce low-nicotine plants. Europeans were ahead of the curve in this respect, and by the 1930s Germany’s state-financed (pro-)tobacco research laboratory, the Reich Institute for Tobacco Research at Forchheim, had engineered tobacco plants containing very little nicotine: about 0.15 percent as compared with the usual 2 to 3 percent in regular cured leaf. For a one-gram cigarette, this meant 1.5 milligrams of nicotine instead of the usual 20 to 30 milligrams.

Here again—just to remind the reader—we are talking about nicotine content, not nicotine yields or deliveries. The distinction is crucial: content is how much is actually in the cigarette; delivery is how much enters the smoker’s body when the cigarette is smoked in some standardized manner, typically on a smoking machine. Deliveries can vary widely, since smokers can smoke a cigarette more or less intensively—which is why regulators when they decide to limit nicotine in cigarettes must focus exclusively on content, not deliveries. Only reducing the actual content in the rod below a certain amount will prevent cigarettes from being addictive (see again the box on page 380).

Tobacco manufacturers by the early decades of the twentieth century already knew how to quantify the nicotine in smoke and/or leaf and had developed techniques to raise or lower the concentration to any desired level. Nicotine content of the finished product became part of manufacturing specifications, and was controlled quite precisely. Cigarettes were also starting to become more uniform—from the point of view of physical design—for tax reasons and by virtue of how cigarettes were made and distributed. The widespread use of vending machines required a certain uniformity, for example, as did mechanized production à la Bonsack et al.’s equipment. The standard American “Class A” cigarette by the 1930s was 70 millimeters long and contained just over a gram of tobacco; the nicotine content varied somewhat but was typically kept in the 20- to 30-milligram range. There was no point yet in moving outside this range: higher values would have been too harsh, and significantly lower values would have been considered “low-nicotine” specialty items, or worse.

The American Tobacco Company conducted elaborate tests on nicotine-depleted cigarettes at the end of the 1930s, leading Hiram Hanmer to conclude that “The emasculated cigarette, whether produced by removal of nicotine from tobacco, or the use of nicotine-poor tobacco in blending, gives an insipid smoke which is thin, sharp, and lacking in character.” Hans Kuhn of Vienna’s tobacco monopoly agreed that a “moderate” level of nicotine was crucial for maintaining a smoker’s interest; Kuhn had a piquant way of putting it, comparing cigarettes without nicotine to “a kiss from one’s sister.” Philip Morris psychologists would later liken nicotine-free tobacco to sex without orgasm.5

With the “health scare” of the 1950s, however, many smokers started switching to cigarettes offering lower tar and nicotine. Machine-measured yields began to fall in response, as smokers began to shift to what they imagined to be “safer” cigarettes. Questions started being asked about how low nicotine yields could go before cigarette sales would start to suffer; the fear was that if driven too low, people would simply stop smoking—whence all those worries about “weaning.”

This was not a trivial concern. People smoke to satisfy their nicotine cravings, and if they can’t satisfy that urge they won’t keep on with the habit. Surveys show that most people don’t like to smoke and wish they didn’t; they smoke only because they feel it is beyond their control to stop. That is why nicotine-free cigarettes have rarely been commercially successful: “confirmed” smokers smoke for the nicotine, and cigarettes without cannot “satisfy.” Some people may smoke purely for the ritual or the taste, but that is the exception rather than the rule. Cigarettes without nicotine have never been more than gimmicks and curiosities.

Demand for “low-tar” cigarettes continued to grow throughout the 1950s and 1960s, as increasing numbers of smokers imagined this as a way to reduce their risk of disease. So whereas cigarettes in the early 1950s averaged 35 milligrams of tar (on standardized smoking machines), yields by the 1980s had dropped by about half. Part of the decline was from the introduction of filters, along with new blending tricks and burn accelerants, but most was from putting less tobacco in the rod and from ventilation. For a time at least the hope was basically to keep up the nicotine (addiction) while reducing the tar (cancer); Wynder, Russell, and numerous others had proposed this same solution, that the ideal cigarette would be reasonably high in nicotine but as low as possible in tar.

Nicotine can exist in myriad chemical forms, however, and can be manipulated to deliver a more or less powerful nicotine “kick.” There are several different ways to do this, the most notorious of which involves freebasing, the transformation of a molecule from a (bound) salt to a (free) base, typically by adding ammonia or some other alkaline compound. This is one of the most significant developments in the history of modern drug design, and one virtually unknown to the outside world—applied to tobacco at any rate—until the 1990s, when the industry’s internal documents first came to light.6

From a historical point of view, freebasing essentially reverses the trend toward ever milder, low-pH smoke ushered in with the flue-curing revolution. Flue-curing you will recall involved the lowering of cigarette smoke pH from 8 to about 6, making it less harsh and therefore easier to inhale. Freebasing pushes the pH back up a bit, but the purpose of the manipulation is quite different. Flue-curing makes tobacco smoke less alkaline and therefore mild enough to inhale. Freebasing, by contrast, allows the nicotine to volatilize more effectively, making more of it more readily available to the body. “Freebasing” is the street word for the trick as popularized in the cocaine trade, but it was actually cigarette makers that invented the process, or at least commercialized it on an industrial scale. Marlboro was its first great beneficiary: indeed much of the success of this global cowboy brand can be traced to this chemical trick.

But to understand how this works, we need to return again to the nature of smoke and how nicotine gets carried into the body.

Tobacco smoke is interestingly complex. It’s sort of like a moist gassy dust, or dusty gas, containing thousands of different chemicals in myriad complex and changing physical forms. The first step in simplifying this complexity is to realize that smoke has two physical states or “phases”: one composed of particles and another composed of gas. Tobacco smoke is technically an aerosol in this sense, with most of the soot, tar, and nicotine being in chunky little droplets (12 billion per cigarette by one estimate) suspended in a gas consisting of carbon monoxide and dioxide along with water vapor, nitrous oxides of various sorts, hydrogen cyanide, nicotine in a gaseous state, and other gases not bound to the tiny droplets.7

The particle phase consists of everything that can be condensed from tobacco smoke when you apply an electric charge to these droplets and pull them down onto an electrostatic filter (also known as a Cambridge filter). This will include all of those tiny charred chunks of matter known as “soot,” along with most of the greasy-waxy compounds known as “tar,” plus whatever other solids or viscous liquids fall out when smoke is pulled across that electrostatic filter. A 1965 Reynolds document comments on how several different names have been given to this particle phase, including “tars, smoke solids, solids, total solids, particulate matter, total particulate matter, smoke condensate, total smoke condensate and smoke condensables.”8

The gas phase, by contrast, is everything that cannot be filtered out—things like carbon monoxide and cyanide gas. These can be measured by techniques such as gas phase chromatography, developed by tobacco industry chemists in the years after the Second World War. The existence of such chemicals is one key limitation of “filtration” in the cigarette context, and one reason cigarette makers never like to talk about “gas” in cigarette smoke. Tobacco researchers for a time explored gas phase properties of smoke to find out whether they could eliminate some of these nastier constituents; great hopes for such a possibility were expressed in the 1950s, though by the 1960s and 1970s most hopes for “selective filtration” had been abandoned.

Like a number of other compounds in tobacco smoke, nicotine is present in both particle and gas phases. It is a small molecule and can either stand alone as a free base or bind to other compounds in the form of a salt—like nicotine citrate or acetate. In its stand-alone form it tends to move more easily into the gas phase of smoke—because the free base is more volatile.9 This is crucial for understanding the logic of freebasing, since (1) free (or free-base) nicotine is far more potent than nicotine in the bound or salt form; and (2) how much nicotine ends up in the particle or gas phase has a lot to do with how acid or alkaline the smoke is. Increase the alkalinity, and you increase the proportion of nicotine in the gas phase. Reduce the alkalinity, and you push the nicotine back into the more inert particle phase. Free nicotine is more easily volatilized and more easily absorbed through bodily tissues. All of which means that by manipulating the pH of tobacco smoke you can influence how potent it will be when you inhale it.

This may come as a surprise to some readers, that smoke can be alkaline or acidic. The crucial take-home fact, though, is that free nicotine packs a more potent punch than bound or salt form nicotine.10 The physiology is not entirely understood, but free nicotine seems to reach the lungs more efficiently, from where it passes into the blood and then into the brain—whereas nicotine in the particle phase is more easily expelled from the lungs or otherwise slowed in its transit to the brain. The difference may have to do with the fact that free nicotine is more lipophilic—literally, “fat-loving”—allowing it to pass more easily through the fatty membranes surrounding the brain.

The freebasing of nicotine goes back a long time, even prior to the industrial manufacture of cigarettes. A similar chemistry is implicit in what I like to call “folk freebasing,” which many traditional cultures use to augment the potency of their preferred alkaloids. No one knows how the practice originated, but rural people in many parts of the world chew tobacco mixed with lime (calcium oxide, not the fruit) to sharpen the punch of the alkaloid.11 Some cultures even urinate on the tobacco as part of the curing process, with the alkaline urea—an ammonia compound—doing basically the same trick. The freebasing of cocaine hydrochloride into “crack” is based on a similar chemistry: the cocaine alkaloid is far more potent in its free base form than as a salt, so bicarbonate is used to transform cocaine hydrochloride into chemically pure crack cocaine.

How, though, was freebasing discovered by tobacco manufacturers? The basic chemistry behind freebasing was already well known to chemists—including tobacco chemists—by the 1930s and 1940s. I’ve mentioned Parmele’s 1946 discussion of adding ammonia to cigarettes to make the nicotine more volatile, but there are even earlier discussions. American Tobacco Company researchers in 1930 reflected on the fact that “Ammonia has the property of setting nicotine free from its salts. If tobacco contains nicotine in the free state, it will be taken up by the smoke more readily, whereas the salts are not volatile to the same extent and the nicotine will be consumed on burning.” German and Russian tobacco experts also knew about the potency of free versus bound nicotine and wrote extensively on this topic.12

There was not much practical use for such ideas in the 1930s and 1940s, however. There was not yet any reason to augment nicotine’s punch, so the question of free versus bound nicotine was little more than a chemical curiosity. Cigarettes still contained high levels of nicotine—typically 20 to 30 milligrams per stick—and the idea of increasing its impact wouldn’t have served any useful purpose. Tobacco manufacturers were far more interested in making cigarettes milder and had no reason to give them any extra jolt. Claude Teague in 1954 was typical in still trying to find out how to reduce the free nicotine in burley leaf: the harshness (or “strength”) of burley was known to come from the “high smoke concentration of free bases,” and Teague actually proposed adding organic acids (citric, malic, or succinic, for example) to the tobacco to reduce this alkaline harshness. The proposal was hardly a new one: the Russian tobacco chemist Aleksandr Shmuk had made virtually identical proposals nearly a quarter of a century earlier. For Teague, as for everyone else in the tobacco world up to that point (circa mid-1950s), the quest was for an ever milder smoke, to facilitate inhalation and to comfort anyone worried about “irritation.” And to encourage novices.13

Chemical priorities changed, however, with the push to develop low-delivery “health reassurance” cigarettes. Cigarette companies in the 1950s and 1960s started wanting to lower tar and nicotine as far as possible without weaning smokers from the habit. So the question became, not just how low can we go, but also how can we squeeze more power out of a given quantity of nicotine? How can we maintain “satisfaction” while lowering (apparent) deliveries? Finding answers to such questions became increasingly urgent, especially after governments started requiring publication of tar and nicotine values (in the late 1960s) from machines in which cigarettes were smoked in some standardized manner. Ventilation was one response; freebasing provided yet another, albeit by accident and through a rather circuitous route, involving ammonia and the processing of tobacco scrap.

Ammonia has long been used in tobacco manufacturing, long prior even to its recognition as a freebasing agent. The earliest patents go back to the 1880s, when the compound was proposed as a means to eliminate the “bad odor” of fermented leaf. More often, though, ammonia was viewed as an unwanted irritant generated through the curing process. One early rationale (or rationalization) for American Tobacco’s much-ballyhooed “toasting” was that heat treating would drive off much of the cured leaf’s accumulated ammonia: the goal was to chase a noxious irritant but also to lower the potency of the nicotine delivered to the smoker by keeping more of it in its bound (vs. free volatile) state.14 Ammonia was occasionally added to tobacco but this had nothing to do with freebasing: I’ve mentioned deodorizing, but ammonia was sometimes used as a solvent to denicotinize tobacco and for a time even (in the 1950s and 1960s) to neutralize carcinogens such as benzpyrene. But the innovation that led to its use as a freebasing agent came from its role in the manufacture of reconstituted tobacco.

Reconstitution is a process whereby parts of the tobacco plant formerly tossed as waste are transformed into a pressed paper sheet, through a technique closely akin to papermaking. “Recon” factories are basically papermaking mills, where huge vats of crushed-fiber tobacco-stem slurry are floated into twelve-foot-wide sheets, which after drying get sprayed with “casings” of various sorts—including nicotine and diverse flavorings and preservatives. One could say that recon is basically to tobacco as plywood is to wood, but the process is really more like papermaking, which is why papermaking unions often represent the workers at such plants (United Paper Workers International, for example).15

Ammonia was added to recon beginning sometime in the late 1950s, principally to make fibers from the woody stems and ribs of the tobacco plant more smokable. German tobacco makers had started including these woody stems in cigarettes during the Second World War, as part of an effort to squeeze more smokable substance out of every pound of harvested leaf. This increasing use of stems was actually thought by some (in the 1940s) to be why cigarettes were causing cancer: cigarette makers had traditionally used only the non-woody parts of the leaf, but with efforts to rationalize production a decision was made to use more and more of the tobacco plant—basically everything but the roots and central stalk—to lower costs and speed mechanical processing.

It was not such an easy thing to make these woody parts smokable, however. The stems are very much like wood, which smokes about like, say, cardboard or sawdust or “brown wrapping paper,” as industry chemists used to say. Nicotine can be added, but the resultant smoke is still quite acidic, which is where the ammonia came in. Ammonia was added to neutralize the acid but also to release the pectins in the leaf (and stem), allowing a more effective binding of the fibers required to hold the dried slurry sheet together. Research into this process of reconstituting tobacco (to make recon) intensified in the 1950s, and between 1952 and 1994 at least 231 patents were filed on the process. R. J. Reynolds was a key early player: the company’s official historian recalls a 1946 journey by three company managers to the public library in Winston-Salem to research techniques of papermaking,16 and by the end of the 1950s most of the majors were using at least some recon in their cigarettes. Some companies had earlier used recon for cigar wrappers, but Reynolds was apparently the first to use it in American cigarettes. The paperlike tobacco sheet is chopped into threads to look much like the chopped leaf itself, and much of what one smokes in a cigarette today is actually recon, which gives the companies a certain flexibility in how to manipulate the final product.

Tobacco manufacturers had hoped that recon would be acceptable to smokers, but no one imagined how seductive it would become. Adding ammoniated tobacco sheet to traditional leaf gave the resulting blend a new and delightful flavor, described in industry documents as a rich burley or “chocolaty” taste. Even more important, though, were its pharmacologic effects, since ammoniation also gave tobacco a more powerful nicotine punch, gram for gram. In the health-conscious climate of the 1960s and 1970s, this meant that manufacturers could continue to reduce the (machine-measured) deliveries of cigarettes while still giving them the nicotine kick expected from “full flavor” brands.

Philip Morris was apparently the first to realize that ammonia could be used to produce this delicious, extra-added kick. The discovery seems to have come about by accident, in the early 1960s, as the company was conducting experiments on the taste and psychopharmacology of ammoniated tobacco sheet. As at Reynolds, ammonia was being added to tobacco sheet to improve its binding properties, giving it the tensile strength needed for processing into cigarette “filler.” (A high sheet strength allowed recon to be pulled rapidly through automated machinery for processing.) Early taste tests were satisfactory, and in 1961 the company set up an experimental pilot plant to manufacture ammoniated tobacco sheet, using the so-called DAP-BL (diammonium phosphate–blended leaf) process.

Philip Morris engineering reports from this period note that the company’s new DAP-BL process was economical, eliminating the need for “stem soaking, stem cooking and stem refining,” but there were also good signs on the taste front. On November 6, 1962, Philip Morris chemist John D. Hind wrote to the company’s manager of development, Robert B. Seligman, commenting on how treatment with DAP had produced a particularly strong “flavor of chocolate,” allowing “a much more efficient way of producing the chocolate ‘notes’ in cigarettes and packages.” It took some time to gear up for production, though, and lots of different variations on this DAP-BL process were tried, including the addition of “a methanol-washed lemon albedo” that gave “a favorable flavor variation.” Process and equipment testing of pilot runs continued through the spring and summer of 1963, and after ironing out a number of potential kinks a decision was made to start commercial manufacture on October 15, 1963.17

Ammoniated tobacco sheet was first incorporated into Marlboros on a large-scale basis in 1964, and it is important to realize how radically this transformed the fate of the cigarette. The factory-scale use of ammoniated tobacco sheet—coincident with the launch of the “Marlboro Country” campaign—worked wonders for Philip Morris and its flagship brand. Marlboro had always been a relatively minor brand and in the 1950s had never garnered even a 5 percent share of the American market. By 1967, however, when Philip Morris secured a patent on its DAP-BL process—making no mention of freebasing, interestingly—Marlboro was well on its way to becoming the world’s most popular cigarette. Market share in the United States alone grew from 5 to more than 40 percent from 1965 through 2005, the most spectacular rise of a single brand in cigarette history.18 Marlboro surpassed Winston as America’s most popular cigarette in 1976 and would soon become the world’s number one brand. Charts of the brand’s market share in the United States show a sharp kink upward in 1964, when the freebased version came on line.

It is impossible to say how much of the success of Marlboro is due to freebasing and how much to the sophisticated marketing of Marlboro Country and the Marlboro Man. Hard-packed and masculine with its bright-red-roof chevron, the brand was perhaps even tough enough to stand up against cancer. (Recall that this manly image was new in 1955, when Marlboro was transformed from a woman’s into a man’s brand. In its feminine incarnation Marlboros had been “mild as May” with “ivory tips to protect the lips.”) Smokers, and especially young smokers, seemed to like the new version’s quick jolt, prompting envy and imitation from other manufacturers. Philip Morris would eventually apply its freebasing techniques to several of its other brands—notably its low-tar (and low-nicotine) Merit cigarettes, introduced in 1976 as “a radical breakthrough in cigarette technology.” Merit was Philip Morris’s hope for a new generation of smokers seeking a “safer” smoke; the new brand advertised a nicotine yield only half of that offered by Marlboro but by virtue of treatment with diammonium phosphate still delivered the same amount of free nicotine to smokers. Brown & Williamson scientists reflected on this in 1980, commenting that “in theory a person smoking these cigarettes [Merit and Marlboro] would not find an appreciable difference in the physiological satisfaction from either based on the amount of free nicotine delivered.”19

Philip Morris enjoyed a monopoly on ammonia technology for a number of years, but the “secret” and “soul” of Marlboro was eventually found out. (Cigarette makers have a long history of reverse engineering their competitors’ brands, to learn what kinds of tricks they might adopt.) Marlboro’s success led to intense efforts at imitation, which is how the other companies came to discover the virtues of freebasing. Liggett & Myers in 1971, for example, tried to elevate its smoke pH by adding calcium hydroxide to its blends, with the following rationale: “We are interested in developing a cigarette with increased smoke pH in order to increase the free base as opposed to acid salt form of nicotine in smoke, perhaps giving a more satisfying smoke. If this could be done there could be a reduction in total nicotine in the smoke without a reduction in the physiological satisfaction associated with nicotine.”20 The author of this report knew that the “physiological effect” of nicotine could be increased by altering this ratio of free-base to acid-salt forms; here, too, the goal was to increase the alkaloid’s strength while lowering apparent deliveries.21

Reynolds was another avid imitator. In 1973 Claude Teague, author of the “Survey of Cancer Research” and now assistant director of research at the company, wrote a long analysis of Marlboro’s success, attributing the popularity of this brand, especially among young people, to Philip Morris’s use of ammonia technology. Teague explored a number of different reasons for Marlboro’s success—along with Brown & Williamson’s Kool—with the goal of helping his company close the gap. His conclusion: “the most significant difference between our brands and Philip Morris brands and Kool has been in the area of smoke pH.” In this same 1973 report—stamped “Secret”—Teague noted that by comparison with Reynolds’s own Winston brand, Marlboro showed “1) higher smoke pH (higher alkalinity), hence increased amounts of “free” nicotine in smoke, and higher immediate nicotine “kick,” 2) less mouth irritation, [3] less stemmy taste and less Turkish and flue-cured flavor, and 4) increased burley flavor and character.”22 Seeking to capture this allure, Reynolds began ammoniating its own cigarettes shortly thereafter. In 1974 the company started using ammoniated sheet in the manufacture of its Camel filters, allowing them to deliver 36 micrograms of freebasing ammonia in the mainstream smoke of each cigarette. Reynolds researchers here again reasoned that people were turning to Marlboros because they delivered more free nicotine as a result of ammonia technology.23

Brown & Williamson was yet another convert. By 1965 scientists from the company’s parent BATCo laboratories in Southampton were well aware that the “strength” or “impact” of a cigarette was related not to total nicotine delivered but rather to the amount of “extractable” or “free nicotine,” which varied significantly with smoke pH. Ammonia was an obvious way to manipulate smoke pH, and by 1971 the company had given the code name UKELON to urea, an ammonia source recognized as “a way of achieving normal impact from low tar cigarettes.” Free nicotine was “more readily absorbed” and therefore more likely to have “a decidedly satisfying effect on the smokers’ taste receptors.” The company’s Project LTS (Low Tar Satisfaction) was designed to exploit this effect, with the goal being to create a cigarette containing “greater levels of ‘free’ nicotine” in “an enhanced alkaline environment.” A 1971 Brown & Williamson document titled “Ukelon Treatment of Tobacco” noted that urea treatment could be “one avenue toward the development of a low-tar, full-impact cigarette.”24

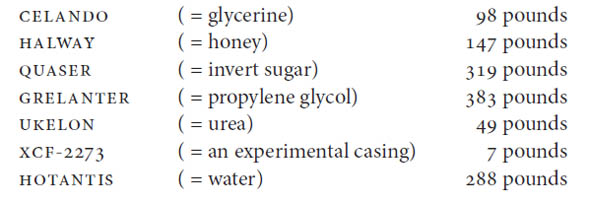

Brown & Williamson continued research along these lines throughout the 1970s and by 1980 was able to conclude that “we have sufficient expertise available to ‘build’ a lowered mg tar cigarette which will deliver as much ‘free nicotine’ as a Marlboro, Winston or Kent without increasing the total nicotine delivery above that of a ‘Light’ product.”25 UKELON by this time was being used in the company’s Kool and Viceroy brands, and we even have some of the recipes detailing how many pounds were sprayed (as “casing”) onto the finished blend per hogshead of tobacco. Casing for a ten-thousand-pound batch of the company’s experimental MT-768 tobacco in 1989, for example, included the following ingredients:26

The recipe provides only the code names; I have given here the decoded ingredients in parentheses. We also have the mixing instructions: HOTANTIS (= water) was to be added at 120 degrees Fahrenheit prior to a “drop to solids tank,” following which UKELON (urea) would be added and mixed for ten minutes. The special “casing” (flavoring) XCF-2273 was then added along with the glycerine, honey, sugar, and propylene glycol, followed by application to the tobacco at 120 degrees Fahrenheit. This was all part of the company’s Project Best, the goal of which was to develop a cigarette to outperform archrival Marlboro. With a key question being: “Is there more NH3 [ammonia] chemistry in Marlboros”?27

This question was of great interest to Brown & Williamson, which is why they hired a corporate intelligence service to investigate how much ammonia Philip Morris was using. In 1985 the Corporate Intelligence Group of a company known as Information Data Search, Inc., reported to Brown & Williamson on the results of a clandestine inquiry into Philip Morris’s ammonia usage, pieced together from interviews with chemical suppliers, tobacco growing experts, equipment manufacturers and distributors, fragrance and flavor specialists, chemical engineers, and competing cigarette manufacturers. Brown & Williamson learned by this means that its chief rival was using about 2.5 million pounds of gaseous ammonia per year at its American manufacturing plants.28

By this time, however, virtually all the majors had learned how to use ammonia technology—and not just in the United States. In January of 1988 J. S. C. Wong from Research and Development at W. D. & H. O. Wills in Australia reported on his company’s efforts to use ammonia to develop a “low alkaloid smoking product without adversely affecting Smoking properties.” Wong had reduced the nicotine content in a tobacco blend by water extraction and noted that subsequent exposure to ammonia “restored impact and irritation levels to a similar order of magnitude as those for the unextracted tobacco.” Wong also remarked on the “smoother smoke” produced by ammoniation.29

New methods to measure nicotine’s impact were also developed, including the so-called Woodrose technique, which ranked the subjective impact of a particular cigarette on a scale from 1 (low) to 4 (high). In the early 1970s this was part of an elaborate testing mechanism by which cigarettes would be rated for impact, irritation, and flavor, and on this basis awarded different “amplitudes” or “scores.” Impact was basically nicotine “satisfaction,” irritation was how much a cigarette bothered your mouth or throat, and flavor was, well, flavor. Each of these was further broken down into subcategories. Irritation could be different in the mouth, nose, or throat, for example; and flavor could be “musty,” “earthy,” “green/grassy,” “dirty,” “roasted/toasted,” and so forth. Tobacco manufacturers spent a lot of time rating cigarettes in this manner, with test panels assembled to evaluate different blends and additives. Experts were also hired in the area of “sensory science,” with the hope of creating some of the same kinds of scales fashionable among wine connoisseurs. Summary instruments of various sorts were developed, including a “Tobacco Aroma Wheel” comparable to what wine critics had in the form of “wine wheels” to evaluate cabernet, pinot, and chardonnay.30

Ammonia technology by the 1980s had become routine in cigarette manufacturing. An Ammonia Technology Conference organized by Brown & Williamson at Louisville, Kentucky, on May 18–19, 1989, concluded that ammonia technology was “the key to competing in smoke quality with [Philip Morris] worldwide.” Minutes from this meeting reveal that with the exception of Liggett, all U.S. cigarette manufacturers were using some form of ammonia technology by this time. Philip Morris was using DAP recon and urea; Reynolds was using ammonia gas; American and Lorillard were using DAP recon; and Brown & Williamson itself was using DAP recon and urea, code named QUELAR and UKELON, along with half a dozen other tricks under the rubric “Root Technology.”31 Controlled ammonia processing was identified by Brown & Williamson researchers as “the soul of Marlboro”:

Marlboro is a moving target. Its blend alkaloids have markedly increased over the last three years. Humectants levels have increased. We find increasing amounts of two PM additives, urea and propyl paraben, in Marlboro. . . . We stand on our prior conclusion that the soul of Marlboro is controlled ammonia processing of tobacco, with this processing being accomplished during reconstituted tobacco manufacture. PM’s band-cast recon most efficiently accomplishes the desired ammonia chemistry, thus it is an essential ingredient in Marlboro.32

None of this, of course, was made public, and the companies for many years denied they were manipulating nicotine. Philip Morris was actually brash enough to sue ABC Television—in 1994 for $10 billion—for reporting that Marlboro’s maker had been “spiking” its cigarettes with nicotine.33 The irony is that the companies could have made a case that freebasing was simply a way to increase the potency of the nicotine while keeping down the tar; freebasing could have been defended as a means of creating a “safer cigarette.” Wynder and others had championed this idea, that nicotine-to-tar ratios should be maximized, keeping the nicotine high and the tar low. The companies never made this argument, because they didn’t like to talk about how they were manipulating the chemical properties of smoke. They also didn’t want to admit that nicotine was addictive. The companies could have said they were trying to make a low-tar cigarette while keeping “satisfying” levels of nicotine, and some public health authorities might even have hailed this as a noble goal.34

Making such an argument, though, would have compromised one of the pillars of the industry’s deception, which was that nicotine was simply one of the many “taste” elements in a cigarette and in no way craved by smokers, robbing them of their self-control. The public had been led to believe that nicotine was just one of many natural constituents of tobacco leaf, beyond the control of the manufacturers. Admitting they were juicing up its potency while promising ever lower deliveries would seem to have required admitting addiction, which they were not yet willing to do. Not to their customers at any rate. The official line was always that ammonia was added simply to improve the “taste” of tobacco.

Privately, however, the companies were quite upfront about free nicotine being a more powerful—and dangerous—form of the alkaloid. Free nicotine was always a health and safety concern on the tobacco factory floor, where leaf-processing equipment would routinely gum up from contact with the waxy alkaloid. And to clean such equipment, the companies would often engage in what we might call “de-freebasing,” wiping nicotine-clogged machine parts with citric acid to convert the volatile free base into a more harmless (acid) salt. Nicotine in its free base form is extremely toxic, and manufacturers knew that contact with even a few drops could prove fatal—by direct absorption through the skin. Confidential safety protocols for Philip Morris’s pilot plant making denicotinized tobacco for the company’s Next brand cigarette recognized that “The use of citric acid when decontaminating a piece of equipment serves to convert nicotine free base to the less readily absorbed salt form, at the same time rendering it less volatile.” The resulting salt—nicotine citrate—was still quite toxic but now at least had the “advantage” of having “only about one twentieth the rate of skin absorption as free base nicotine.”35

Another problem with admitting nicotine manipulation stemmed from the fact that cancer is not the only harm from smoking. Smoking also causes heart disease and dozens of other maladies, in which nicotine is not entirely innocent. Nicotine has been implicated in cardiovascular disease—by causing constriction of the arteries—and contributes to death from stroke and possibly even cancer. John Cooke at Stanford has shown that nicotine stimulates blood vessel growth, which means that exposure to nicotine might well promote tumorigenesis, by helping to supply new tumors with oxygen-rich blood. And scholars have shown that nicotine may be involved in blocking some of the enzymatic activities that help to detoxify tobacco-specific nitrosamines.36 Pharmaceutical companies even today are hamstrung in their development of new drugs, since nicotine interferes with basic detoxification processes in the body.

The bottom line is that freebasing helped sustain mass addiction. Smokers thought they were buying low-yielding cigarettes, when in truth they were getting just as much nicotine—and in a more powerful form. Freebasing was a response to worries that falling nicotine yields might cause people to quit; the point was to increase the “extractable” nicotine in smoke, delivering a higher nicotine kick per milligram of the alkaloid. The process was deceptive, in that it was introduced into many of the same brands advertised as “light” or “lower yield.” So even though tar and nicotine levels measured by automated smoking machines showed steady declines over time, the augmented impact kept customers as addicted as ever. Freebasing facilitated compensation and is best regarded as a form of chemical deception, a subterfuge to keep smokers coming back for more.

This history—and chemistry—now has regulatory implications, since the newly empowered FDA will probably try to establish some maximum allowable limit to how much nicotine will be allowed in cigarettes, to prevent addiction. The industry will surely resist any such effort, but if some reasonable upper limit is established (see again the box on page 380), the companies may try to game this by reducing the size of cigarettes (to keep a high fraction of nicotine per puff) or raising the pH of the resulting smoke or adding other kinds of chemicals to make sure smokers remain hooked. Regulators will have to guard against industry efforts to increase the potency of nicotine by other means, or even to de-freebase cigar smoke to make it inhalable. The companies may try to exploit nicotine–acetaldehyde synergies, or to add other addictive compounds. Skirmishes of this sort will probably drag on for years, consuming costly financial and intellectual resources, before the courage will finally be found to cut the Gordian knot and ban combustible tobacco products altogether.