The belief that cigarettes contain only pure, unadulterated tobacco is almost universal among smokers . . . they are blissfully ignorant of the ungodly messes of which they are composed.

HERMAN SHARLIT, “CIGARETTE SMOKING AS A HEALTH HAZARD,” 1935

There’s an old saying in the food business, that people will eat almost anything if you grind it up fine enough. With food of course there is a certain amount of oversight, and acute poisonings attract attention. But with tobacco the situation is different. Cigarette makers have had virtually unlimited freedom to add whatever they want to cigarettes—whether to elevate sales or reduce costs or kill mold or prolong shelf life or make handling by machinery easier. Or to supercharge the nicotine or to appeal to the youthful sweet tooth. And given the fertility of the tobacco man’s mind, some remarkable things have been added. Tobacco chemists put a breathtaking variety of additives into tobacco leaf, cigarette paper, and packaging foils: flavorants and moisturizers, of course, but also impact boosters, burn accelerants, fire retardants, bronchodilators, smoke particle size reducers, and a broad palette of coloring and bleaching agents.

And that’s just what is there by design. Smokers may think they are smoking cured tobacco leaf, but there is actually quite a bit of other stuff in cigarettes—some of which enters just by chance. The industry doesn’t like to admit it, but we know from their internal archives that unwanted filth sometimes makes its way into cigarettes. This includes shards of metal or glass but also substances that enter through rough handling in the growing stage—dirt, sand, and pesticides, for example, but also grease from the machines and even chemicals that gas off from the cellophane.1 The list of contaminants is long.

Before diving in, though, we should appreciate that additives and contaminants have never been high on the list of things that tobacco’s critics worry about,2 given that the “pure” cured leaf by itself is so toxic. What difference does it really make that a company is adding dangerous chemicals if “natural” tobacco is already super-deadly? American Spirit’s much-hyped “natural” cigarettes are no less deadly than any other kind, despite having a Native American on the pack. The same with China’s popular “herbal” brands. Worrying about whether your tobacco is natural or organic is like worrying about whether the fecal pellet in your cereal was excreted by a caged or free-range rat.

There is another oddity we must keep in mind. The industry has long maintained that it uses only “approved” food additives, which makes about as much sense as the rat pellet point. For many years this additives list was a closely guarded secret, and even today we know more about the constituents of cat food—which should give smokers pause. But think for a moment about this “approved food additive” point. A fruit salad eaten is quite different from a fruit salad burned and inhaled. Almost any complex organic mixture will be toxic when pyrolyzed and drawn into the lungs, and you can be sure that a fresh fruit salad dried, burned, and inhaled will not do you any good. And the same is true for many of the additives forced into tobacco. Sugar may be relatively safe when consumed in moderation (apart from cavities and the like) but when burned in a cigarette will produce acetaldehyde, a carcinogen. Glycerine is likewise innocuous when eaten but when combusted produces acetaldehyde and acrolein, carcinogens both. Protein is also of course an essential nutrient—in food—but quite toxic when burned and inhaled. Burning protein produces nitrosamines, among the deadliest of all carcinogens. (Philip Morris scientists in 1963 characterized nitrosamines as “the most potent carcinogens known,” with the dosage needed to produce cancer being “exceedingly low.”) So it is ridiculous to say that some specific cigarette ingredient is “generally regarded as safe” (GRAS)—as we so often hear from the industry.3 The entire concept of GRAS is intended solely for foods, not for substances burned and inhaled. The confusion is bizarre and a typical tobacco subterfuge of the facts.

So let us ask again: What is in your cigarette? Here are a few of the choicer items, with some of the history behind how they got there.

Arsenic and lead became a hot potato in the 1930s and 1940s, when lead arsenates and arsenites were widely used as pesticides—on tobacco but also on many kinds of food crops. Catastrophic poisonings in the 1930s inflamed the press, as when dozens of laborers in the Moselle Valley (near Germany’s border with Luxembourg) died after spraying the compound on grapes. Some died from drinking wine made from the grapes, and autopsies showed that many of these victims had tumors.4 No one knows how many people perished from handling the pesticide—or from the arsenic that lingers even today in cigarettes.

By the early 1930s the tobacco industry had already started hiding what it knew about arsenic. A letter of 1932 to Lorillard’s vice president detailing the arsenic content in “Plain Havana Blossom” chewing tobacco, for example, began by noting, “Since we understand that considerable secrecy has been maintained relative to the subject, we are taking the liberty of writing you this report in long-hand, and trust that you will be able to make it out.” Lorillard measured an average of 2.8 parts per million (ppm) arsenic in its tobacco, though other investigators had been finding up to 30 ppm in the actual smoke. Pesticides were one principal source, but Henry Ford—the carmaker and cigarette critic—as early as 1914 had reported arsenic being used (along with lime and lead) to toughen cigarette paper and that solutions made from paper treated in this manner had enough poison in them to kill mice.5

Lead got into cigarettes the same way as arsenic—mainly from lead arsenate pesticides—but there were other sources. The metal was commonly used in the foil used to wrap cigarettes, for example, a practice not banned in the United States until the 1940s—by the War Production Board, interestingly, which implemented the ban not to protect human health but rather to safeguard the nation’s supply of metals for making ammunition. Leaded gas was also sometimes used as a fuel for cigarette lighters, which must have caused some inhalation. Pesticides, though, were clearly the predominant source, with the Consumers’ Research Bulletin already by 1936 proposing as a cynical cigarette slogan: “Have you inhaled your lead and arsenic today?”6

Agricultural spraying of arsenic was drastically cut back after the Second World War, causing measured levels of both arsenic and lead in cigarettes to decline. Unpublished studies done by the Imperial Tobacco Company had documented a gradual increase in As2O3 in unburned leaf throughout the 1930s and 1940s, with the highest values (51 ppm) recorded in 1947. Many scholars at this time—Richard Doll, for example—thought arsenic might well be the principal carcinogenic agent in cigarettes, and speculations were sometimes voiced that eliminating the element from smoke might make cigarettes less deadly.7 Arsenic levels in smoke have fallen ever since, with smokers today inhaling only hundreds of kilograms per year, compared with the hundreds of thousands of kilograms from previous decades. With the phasing out of arsenic insecticides, however, one ogre was simply replaced by another with just as many warts—which brings us to the synthetic pesticides of the postwar era.

People in the tobacco trade apply a wide variety of chemicals while growing the plant, weeding the fields, curing and aging the leaf, and rolling and packing the final product. Chemicals are used to save on time or human labor but also to keep the plant from being attacked by pathogens of one sort or another. Much of what the industry worries about in terms of “tobacco and health” is actually damage to the tobacco plant—from microbes like the tobacco mosaic virus or a bacterium of some sort but also molds, fungi, and myriad insect pests. Treatments generally involve spraying the soil, plant, or stored leaf, often with chemicals that end up as residues in groundwater or the cigarettes people smoke.8 The threats are diverse, as are the compounds used to combat them.

Blue mold and black shank, for example, are prevented by sprayings with fungicides such as mancozeb, a carbamate nerve toxin also known to cross the placental barrier. Metalaxyl is often applied, though this benzenoid fungicide is feared for creating resistant strains in other crops. (Farmers consult the online Blue Mold Forecast System, which identifies outbreaks.) Powdery mildew is thwarted by sprayings of dinocap and benomyl, black root rot with methyl bromide and soil sterilants such as chloropicrin. Bacteria also attack the plant, causing black leg, hollow stalk, and barn rot, treated by methods similar to those used to control nematodes. Nematodes—tiny subterranean roundworms—attack the tobacco plant by roosting in the roots, where they form galls and promote the growth of fungi, causing black shank, fusarium wilt, and black root rot. Nematodes are beaten back with fumigants such as ethylene dibromide, Aldicarb, 1,3-dichloropropene, and methyl isothiocyanate.

Integrated pest management has become the fashion here as elsewhere, but chemical insecticides remain a big part of the tobacco world. Cutworms are controlled by sprayings around the base of the plant, and white grubs and false wireworms are countered by soil fumigants. Similar chemicals are used to combat aphids, flea beetles, grasshoppers, hornworms, loopers, stinkbugs, thrips, leaf miners, tobacco slugs, stem borers, and whiteflies. Predators attack the tobacco as it is stored, so dimethyl dichlorvinyl phosphate is used to control the cigarette beetle and tobacco moth, two predators that alone chew up hundreds of millions of dollars worth of tobacco stocks every year—and that’s just in the United States. Cigarette beetles are found at all stages of manufacturing, presenting the specter not just of economic loss but also of cigarettes contaminated by “insect corpses or byproducts” such as feces and body oils.9

So even though pheromone traps and the like are sometimes used to catch cigarette moths, a great deal of poison is still sprayed on or around the leaf at one stage or another. Many such chemicals are hard to handle safely but can also be hazardous for smokers who inhale the residues and for wildlife wherever tobacco is grown. Many tobacco pesticides harm birds or cause soil depletion; some, like methyl bromide, are notorious ozone depleters. Applications tend to be quite heavy, with some tobacco crops receiving as many as sixteen different treatments. One of the most widely used is maleic hydrazide, a “suckering” agent that deserves some special remarks.

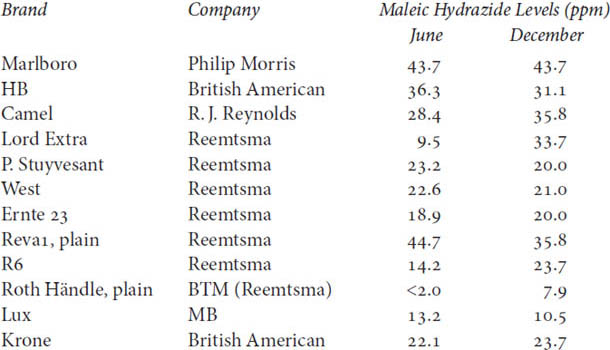

Plants often do things farmers don’t like, and one of these is to sprout where they shouldn’t be sprouting, depriving already established leaves of energy for growth. To prevent this, tobacco farmers apply suckering agents, the most popular of which is maleic hydrazide (MH-30), a growth retardant used to remove new shoots from the stalk of the plant after topping. (Topping involves removing flower tops to concentrate growth in the leaves.) The compound has been recognized since the 1960s—even by the industry—as a carcinogen, but farmers have been reluctant to give it up. In Rhodesia, present-day Zimbabwe, the compound was actually banned for use on tobacco in the early 1960s. Today, though, it is still widely used, and residues can be found in most cigarettes. Philip Morris in 1987 launched Project Moon to monitor contamination and found the following levels in European brands, measured in parts per million.10

Cigarettes weigh about a gram, which means that if a trillion were being smoked in any given year (which is about right for Europe at that time) and residues averaged 20 micrograms per cigarette, then the total mass of just this one herbicide in cigarettes smoked by Europeans was about 20,000 kilograms per year. MH-30 residues have been recorded even higher—up to 115 ppm in some samples—with 5 to 7 percent being transferred into the smoke.11

Of course while exposures from any one cigarette may be small, the aggregate over a lifetime can add up—which is significant when it comes to pesticides, given how many thousands of tons are sprayed on tobacco. In the United States alone, according to the General Accounting Office, an estimated 27 million pounds of pesticides are sprayed onto tobacco fields every year. Indeed for non-agricultural workers, inhaled tobacco smoke will likely be the principal means by which smokers are exposed to pesticides—with the mode of delivery being about as dangerous as it gets. Farmworkers are exposed via several different routes, but smokers burn it right into their lungs. Environmentalists have been sounding this alarm for quite some time: Rachel Carson in her 1962 Silent Spring pointed to the cumulative nature of sprayings, causing the arsenic content of American cigarettes to rise more than 300 percent from 1932 to 1952.12

Government agencies have long been granted authority to control such compounds in foods but have never had much power to limit pesticides in cigarettes. Most countries have been apathetic: German authorities in 1988, for example, confirmed their “lack of concern” with residues of methoprene (Kabat Tobacco Protector) on imported leaf so long as it was kept below 10 ppm. And a Philip Morris document from 1991 talks about how Malaysia was being pressured—by the tobacco giant—to increase its tolerance from 1 to 15 ppm.13 Apathy stems in part from the fact that for tobacco control advocates it doesn’t really matter how tobacco kills you; the brute fact is that it does, and the details are, in a sense, a distraction. Another source of neglect stems from the fact that manufacturers rarely alert smokers to the presence of pesticides in cigarettes. Some companies have recently tried to play the “pesticide-free” card: American Spirit cigarettes, for example, are advertised as made from “100% additive-free natural tobacco” and have managed to capture much of this eco-granola market. Reynolds saw this as a growth area in the 1980s and 1990s and set out to buy the rights to this brand (from the Santa Fe Natural Tobacco Co.)—which it did for a whopping $340 million in 2002. Health-conscious smokers in the San Francisco Bay Area are enthusiastic consumers of this naturo-bunkum brand—which makes about as much sense as hoping that the car crashing into you is a fuel-efficient Prius rather than a gas-guzzling Ford.

Pesticides have also been ignored because of regulatory or administrative impotence. Cigarettes have not until recently been regulated by the FDA, so there never has been any full disclosure of what is actually in a cigarette, or virtually any limit on either contaminants or additives. And no requirement to study the health impact of an additive, prior to adding it. So regulatory myopia has encouraged industrial nonchalance. The companies have long fought to keep pesticide residues from being classed as foods (or drugs) and to keep tolerances high in those few countries where pesticides in tobacco are regulated.14 The industry has been largely self-regulating in this realm, which is more like saying anything goes. So when specific additives are discussed, this is most often done under the irrelevant rubric “ingestion,” as if eating a dried leaf soaked in licorice was the same as burning and inhaling it. With the irony that whatever pesticides end up in a smoker’s lungs, even if deadly, might be no worse than the “natural” fumes from gimmicks like American Spirit.

Tobacco manufacturers add flavorants to cigarettes for many different reasons: to enhance pack aroma or “cool” the smoke, to attract the young or beginning smoker, or just to mask the nasty stank of nicotine. Many of these were already in use in the nineteenth century, with old-time stalwarts like cocoa, licorice, and molasses joined more recently by exotics like rose of latakia, imperial prune, and a parade of synthetics from German or Japanese labs. Many of these are described in the industry’s archives, but some take detective work to decipher, as they’re listed only under code names. AMSPIN, CROTAN, and MADMART, for example, turn out to be licorice, cocoa powder, and St. John’s bread. (British American Tobacco began using five to seven-letter code names for additives prior even to the Second World War, continuing a practice from the trade secret-sensitive flavorants industry.)15 Flavorants are often added not for taste at all but rather just to improve the smell of the cigarette prior to combustion—upon opening the pack, for example (“pack aroma” appears in five thousand company documents). The industry has devoted enormous resources to researching the sensory qualities of tobacco and the impact of various additives and has developed an elaborate vocabulary to talk about aroma, impact, flavor, and the like.

Oriental (Turkish) tobacco, for example, is said to have a “cheesy-sweaty-butter odor reminiscent of isovaleric acid,” while other varieties are said to have aromatic notes of wood, leather, dirt, or various animal scents. Flavors are described as bitter, sour, or metallic, or as having a peppery bite or sting. Tobacco researchers developed the science of hedonics to distinguish such sensations, with some industry documents listing more than a hundred different ways to characterize a particular sensory impact or impression, from “putrid” or “fecal” to “malty” or “molasses.”16 Coumarin is used to impart a vanilla-like aroma, and ylang ylang provides a floral scent with notes of jasmine and custard (it’s also used in motion sickness medicines). Balsam of Tolu is added to provide hints of cinnamon, and patchouli oil is added for “earthy notes.” Flavorants include oil extracts from cardamom, cedar, and coriander, juice extracts from prunes and figs, and oddities like Otto of Rose or castoreum, an aromatic oil extracted from the anal glands of Canadian and Siberian beavers. Most of the world’s herbal chests have been probed for this purpose—and scrutinized through “taste tests” in the transnationals’ laboratories.

Some classes of additives have been more successful than others. Lots of fruity and chocolaty flavorants have been tried, along with extracts intended to provide “a good bourbon or whiskey flavor.” In one series of Brown & Williamson tests menthol and cinnamon got good marks, but perfumes and florals didn’t pass. And neither did many spices, which were often judged too sharp or hot. Perfume or floral flavors such as mimosa, jasmine, frangipani, and musk were explored to pretty up secondhand smoke and to intensify the smoking experience. Philip Morris invented its New Leaf brand using wintergreen and a Breeze menthol sauced up with cloves. Saratoga had extra licorice and chocolate; American’s oddly named Mayo brand was tinctured with spearmint. And Brown & Williamson sold a fruity cigarette called Lyme, prior to the rise of the tick-borne disease. None of the companies ever fared very well with raspberry, peach, or banana, though Brown & Williamson apparently used small amounts of each in its cigarettes. Better luck was had with lemon, orange, apple, and cherry, as with brandy, rum, and bourbon—though Winston’s “winey” and “raisiny” notes were thought to have been achieved with flavors of sage. Less successful were efforts to simulate scotch, cognac, or vermouth. For a time great hopes were held out for coffee flavors, with the obstacle being that most such signatures are unstable.17

One reason for many of these intrigues was to replace flavors lost from the rush to “low-tar” cigarettes, but tobacco chemists also hoped that low-delivery products would offer “ideal vehicles for high levels of added flavors.” There was also the hope that new fruity flavors would attract young smokers. Some wild and crazy ideas were explored—like adding opposite-sex-attracting pheromones to cigarettes. Philip Morris researchers in 1978 urged the company to register trademarks such as “Male” and “Female” for this purpose.18

Natural flavorings can be expensive or unstable, which is why the industry has often turned to synthetics. Grape, for example, is approximated by a methyl anthranilate, peach by a complex carbon aldehyde, and banana by an amyl acetate. Many such compounds have code names: AMBROX is an ambergris odor substitute, for example, with the more technical name tetra-methyl-dodeca-hydronaphtho-furan. Coumarin, used to impart vanilla-like aromas, has at least seven different code names and numerous synthetic counterparts. Green apple is achieved with 3-hexenyl propionate, and a “meaty smell” is obtained from hexyl 2 furcate. Hundreds of synthetic flavorants are routinely used in cigarettes, with many being obtained by the ton from chemical manufacturers. Brown & Williamson in the 1970s was using about a dozen suppliers, including Norda (for oil of lime and orange), Firmenich (imitation chocolate), Glidden (peppermint), Gentry (cherry), Givaudan (apple and cinnamon), Fritzsche (mace and bourbon), and Dragoco (coffee). These suppliers obviously knew what their products were being used for,19 so did they ever worry about them being burned and inhaled? Did any such firm ever refuse business from a cigarette company? And what safety tests were ever done prior to shipment? Recall that if only one percent of all cigarette deaths have been caused by burning and inhaling such additives, this would still be a million deaths worldwide during the twentieth century—and a toll growing higher every year.

Tobacco additives have been almost entirely unregulated, which means virtually unlimited freedom to add whatever manufacturers might fancy. If plutonium were not a controlled substance, there would apparently be no obstacle to tossing it into a cigarette. What could be the objection? That it raised the likelihood of death from “high” to “extreme”? The reality is that many known carcinogens have been added to tobacco products. Angelica root extract is sometimes used in cigarettes: the compound appears in more than 1,700 internal industry documents. Safrole was apparently being used in Kent cigarettes in 1990, years after it was banned (as a carcinogen) from soft drinks.20 One document prepared for Brown & Williamson lists over a hundred cigarette additives, from star anise oil to smokanilla, with more than forty designated by the company as “potentially hazardous.” Compounds in this category range from tonka bean and saccharine to diethylene glycol and Dragoco tangerine.21 Additives have included the food dye known as butter yellow (“found to cause liver cancer in animals”), calamus or sweet flag (“banned in 1968 because it caused malignant tumors”), cobalt and its salts (“chest pains resembling heart attacks”), ammoniated glycyrrhizin (“severe hypertension and cardiac arrhythmia”), juniper berries (“nervous system toxins which can cause hallucinations”), lithium chloride (“several human fatalities”), mannitol (“diarrhea, nausea, and vomiting”), and pennyroyal (“can induce abortion”).22

Many of these compounds are used in substantial quantities. Licorice, for example, has been widely used—on a gargantuan scale—as a sweetener in cigarettes. Tobacco manufacturers in the 1980s in the United States alone were putting 12 million pounds of licorice into cigarettes every year, with an estimated 90 percent of all licorice in the country going into tobacco products.23 Along with 35 million pounds of glycerol, millions of pounds of cocoa, and millions of pounds of synthetics of various sorts. These are huge investments: the U.S. tobacco industry spent $76 million on flavorings in 1977 and $113 million two years later. The U.S. Surgeon General in 1981 cautioned that additives might pose “increased or new and different disease risks”; the industry was asked to stop adding new ingredients, a request apparently ignored. The industry likes to be able to say (in effect) that “everything we use can be sprinkled on corn flakes,” but how many people really want to smoke corn flakes? Widespread smoking of corn flakes would no doubt cause lung cancers.

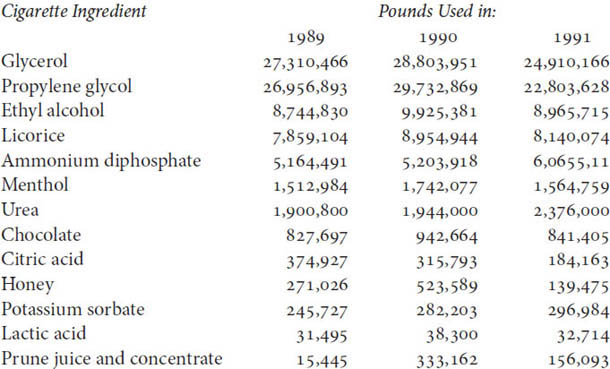

A 1992 Covington & Burling document gives a revealing look into the quantities of hundreds of different ingredients used in American cigarette manufacturing. Here is a (small) sampling from that list:24

I have selected twenty ingredients, but the document from which this is taken includes some 614 distinct compounds. Readers may be surprised to learn that American cigarettes in 1989 contained 9,725 pounds of kola nut extract, 863 pounds of monosodium glutamate (MSG), 34 pounds of myrrh oil, and just over a pound of horehound extract. Or that in 1990 manufacturers were adding 35,324 pounds of maple syrup, half a million pounds of honey, and nearly nine million pounds of licorice.

Many of these are either carcinogens by themselves or produce carcinogens upon burning. A swamp plant known as deer tongue (so named for the shape of its leaves) contains coumarin, a compound with vanilla-like flavors and aromas. Coumarin was originally extracted from deer tongue or tonka beans, with Reynolds alone by 1930 using 1,200 pounds per month in its cigarettes. The FDA banned all use of coumarin in foods in the 195 os, following research showing it causes liver damage. Some cigarette manufacturers may well have cut back, but a 1983 Mother Jones investigation found the compound still being used—and on a fairly large scale. The leaves are gathered from Georgia swamps and pine forests and sold to middlemen, who then turn the herb (“wild vanilla”) over to tobacco factories. American manufacturers in the early 1980s were still buying one to three million pounds per annum, despite its broad recognition as a carcinogen. Reynolds rationalized (to itself) its continued use by claiming that the amounts added were small: a 1981 research department memo (marked “Secret”) noted that “All domestic companies except PM add coumarin to one or more of their cigarette products.” Philip Morris brands contained less than one microgram per gram, but Reynolds’s own Now brand showed 67 micrograms and Carlton 85s a whopping 140 micrograms per gram of tobacco.25 Do smokers know that the cigarette industry has a history of adding known carcinogens to its products?

Menthol was first added to cigarettes in the 1920s, when Axton-Fisher unrolled its “menthol cooled” Spud cigarette containing the peppermint extract. Menthol was already regarded as a medicinal cough suppressant, which is why smokers were advised (in ads) to switch to Spuds “when you have a cold.” Manufacturers used mice to test for toxicity: a 1935 report for Brown & Williamson claimed that the amounts added to Kool, Polar, and Spud cigarettes (from 1.33 to 2.08 mg per cigarette) were below levels thought to be toxic—though here again we find a failure to reflect on the fact that smokers were not ingesting but rather inhaling the compound after combustion—with all the chemical shape-shifting that implied. Brown & Williamson’s research at this point was preemptive: there was not yet any real opposition; the research was undertaken “simply to have it ready in case somebody starts something about mentholated cigarettes being harmful.” It is already here, though, in these 1930s reports, that we find some of the first arguments of the form “There is no more menthol in 60 cigarettes than in 10 to 20 cough drops”: trivialization by creative (and inappropriate) comparison. Yale University scholars working for the makers of Kool cigarettes noted that you would have to smoke twelve thousand a day to “absorb” the same amount of menthol given to patients as internal medication26—which, again, is like ignoring the difference between eating a pistachio nut and inhaling its carbonized remnants.

Synthetics have long been used to achieve the menthol sensation, even though BAT knew by the 1960s that some of these at least were carcinogenic. Brown & Williamson had patented monomenthyl maleate for use in cigarettes, for example, but BAT’s Additives Panel in 1967 expressed their wariness of using such a compound, given that some of its by-products—maleic anhydride, for example—”had been shown to be mildly carcinogenic.” Researchers at BAT raised this issue with the company’s legal counsel, who advised the firm to be “extremely cautious” using such a substance “since it involved a direct allegation of carcinogenicity in a probable pyrolytic product.” Worries of this sort led the firm to explore other menthyl esters: menthyl succinate and triborate, for example.27

Menthol is added to “cool” cigarette smoke and to make it less harsh, which means that mentholation makes a cigarette easier to smoke. Menthol is an anesthetic: it soothes or even numbs the linings of the mouth and throat and suppresses the body’s natural cough reflex. And by making it easier to smoke, it also makes cigarettes more attractive to young or beginning smokers. Brown & Williamson in the late 1980s reflected on how menthol brands were “good starter products,” since new smokers “already know what menthol tastes like vis-à-vis candy.” Menthol today is much beloved by the industry—and few cigarettes nowadays aren’t treated with at least subliminal levels. Which is also why the industry fought so hard to exclude it from the list of sweeteners barred from cigarettes by the Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act of 2009. Strawberry, banana, vanilla, and ten other fruity/sweet additives were banned, but the industry won at least a temporary stay on menthol. The banned flavorings affected less than one percent of the American cigarette market, whereas menthol—the “ultimate candy flavoring” according to Phillip Gardiner of California’s Tobacco-Related Disease Research Program—is the characterizing flavor of more than a quarter of all cigarettes sold.28

Menthols have long been smoked disproportionately by African Americans, which is why cigarette makers were accused of racism in fighting to keep menthols on the market. That charge is not entirely unfounded, given Lorillard’s archival record of explaining menthol’s appeal as part of a purported desire (by “negroes”) to mask a “genetic body odor.” William S. Robinson, executive director of the National African American Tobacco Prevention Network based in Durham, North Carolina, withdrew his support for the FDA bill when negotiators agreed to exempt menthols from the initial ban.29

The FDA in 2010 began hearings on whether to disallow menthol in cigarettes, with a recommendation due on this topic in 2011. The agency is likely to consider not just the incremental hazard but also the fact that menthols are disproportionately smoked by African Americans and other racial minorities. Regardless of whether menthol is found to confer added physical harms from a purely biochemical point of view, the question will be whether this peppermint flavoring poses a hazard by making it easier or more attractive to smoke, or harder to quit. Phillip Gardiner has urged the FDA to consider that by sweetening cigarettes, menthol makes the poison go down easier.

Menthol will be a crucial test case for the FDA’s new authority to regulate cigarettes. If the FDA can ban flavorants that make the poison go down easier, it can presumably also reduce the alkaloid that keeps smokers coming back for more. (Currently it is barred from eliminating nicotine altogether, but nothing prevents it from requiring that it be reduced to, say, 3 percent of current levels, which is certainly technically feasible.) The fact is that anything that makes smoking more attractive will make people more likely to smoke and therefore causes harm. Menthol on these grounds is clearly a threat to public health, as is virtually everything else about cigarettes. There is certainly legal precedent for requiring that cigarettes be made less attractive: tobacco manufacturers cannot advertise on television, for example, which limits their ability to attract customers. Lives will be saved if cigarettes are made less attractive, and eliminating menthol will do just that. Lives will be saved if cigarettes are made less addictive, and reducing the nicotine will do that as well. The FDA has this power, the world is watching, and it remains only to be seen whether the government has the courage to exercise that power pro bono publico.

Postscript: The FDA’s Tobacco Products Scientific Advisory Committee in March of 2011 issued its report on menthol cigarettes, concluding that the minty additive was not just a flavoring agent but had druglike effects, including “cooling and anesthetic effects that reduce the harshness of cigarette smoke.” The report found that while menthols were no more harmful than regulars on a per-cigarette basis, mentholation could make it easier to start and harder to quit: “by reducing the harshness of tobacco smoke menthol could facilitate initiation or early persistence of smoking by youth.” Menthol could also “facilitate deeper and more prolonged inhalation,” resulting in “greater smoke intake per cigarette.” And for those who quit, reminders of menthol from candy or even toothpaste could prompt a relapse.30 No policy recommendations were made, and it remains to be seen what action will be taken by the FDA, if any.

Bronchial dilators have been added to “smoothen” smoke and to facilitate deep inhalation. The industry has tried many different ways to make smoke milder or easier to inhale; menthol is part of this, but so is cocoa and myriad other additives. Cocoa contains a chemical known as theobromine, for example, which acts to expand the airway passages of the lungs. Cocoa has been added to tobacco since the nineteenth century, but it was really only in the 1960s that manufacturers began appreciating its pharmacologic effects. The quantities used are impressive: British American Tobacco in 1978, for example, was adding 1,250 metric tons of cocoa butter to its cigarettes every year, and most other companies were following suit. Synthetics have also been developed. A “proprietary fat” known as Coberine (made by Unilever) has been used as a substitute for cocoa butter, and cocoa aldehyde was in use as a cocoa substitute by the 1950s. Sugar seems to have allied effects, since sugar upon burning produces acetaldehyde, which interacts with nicotine to intensify psychopharmacologic effects. Licorice also seems to have a bronchodilation effect, which is important given the enormous quantities added to tobacco. Tobacco manufacturers talk about reducing irritation by means of “quenchers,” meaning agents with “anesthetic properties such as menthol, terpenoids and other pharmacoactive additives.” Achieving “mildness” has long been a priority of the companies, with researchers investigating “sugar amination during toasting” and “possible effects of antioxidants as scavengers of free radicals.”31 Efforts along these lines reveal how intensively smoke chemistry has been manipulated, once cigarettes came to be regarded as drug delivery devices.

Additives to cigarette paper. We tend to forget that you cannot smoke a cigarette without smoking cigarette paper, which means that whatever goes into the paper also gets smoked. Cigarettes often have brand names inked onto the rod, for example, which means that a bit of ink gets smoked along with each cigarette. Colorants and/or bleachings are often added, and these, too, get smoked—which is not as trivial as it sounds. Cigarette paper has many different chemicals added, from bleachings to make it white to burn accelerants to keep it lit. None of these are present in large amounts, but in the aggregate we are talking about quite a lot of stuff. Even if there is only a microgram of ink on any given cigarette, for example, this still means six million grams of ink smoked worldwide in any given year. That’s more than ten thousand pounds of ink, burned and smoked along with 300,000 tons of cigarette paper. Comparable figures could be given for bleaching and whitening agents. Some of these additives are anything but innocent: in the 1980s, for example, with worries about asbestos in the news, tobacco manufacturers started wondering whether the talc used by cigarette paper makers contained asbestos, the notorious carcinogen. The Ecusta company quietly conducted an investigation, and its suppliers assured the company that no asbestos was in the talc it was supplying—at least not in “detectable” levels.32

The most important paper additives from a health point of view are the burn accelerants—oxidizing agents—added to keep a cigarette lit or to decrease machine-measured deliveries (because the cigarette burns up faster). The most widely used in recent decades have been sodium or potassium citrates, though many other oxidizing agents have been added (nitrates, tartrates, etc.). Additives of this sort complicate the chemicals emitted in the smoke, but their most important impact is on fire safety, since burn accelerants also keep a cigarette lit when tossed or dropped onto the ground—or onto paper or fabric—which can then cause fires. Some large fraction of the world’s thousands of annual fire deaths are made possible by the industry’s use of burn accelerants in cigarettes.

Particulate filth. Particulate filth is one thing the industry tends to take quite seriously, since this poses a threat to the integrity of the machinery used to manufacture cigarettes. Smokers often complain about finding “foreign matter” in their cigarettes, and this has led to further concerns at the level of public relations. British American Tobacco in the early 1990s began working with the Chilworth Technology Centre to develop “experimental systems for separating clean tobacco from contaminates such as paper, carbon particles, filter material and silica.” Techniques explored involved charging the particles by exposing them to some kind of a static electricity, following which they could be removed by exploiting the differential charge imposed.33 It is not clear whether this particular method was ever employed, but the fact that such ideas were entertained shows that contamination was taking place.

Cigarette manufacturers have often used non-tobacco plant materials in cigarettes, and for various reasons. People in times of war, for example, have turned to substitutes when tobacco became scarce. Germans in World War II tried dozens of different alternatives, from dried lettuce and chicory to corn silk and cherry leaves, and the French even before the war were fond of cigarettes and cigars made from cocoa leaves and pods. Kids from the American South used to smoke whatever leafy weeds they could find, calling this “rabbit tobacco.” Tobacco substitutes have been used to save on manufacturing costs, but there has also been a hope that inert substances might lower machine-measured tar and nicotine and provide “health reassurance.” Researchers at the Roswell Park Memorial Institute in Buffalo, New York, conducted an elaborate experiment with cabbage cigarettes in 1964 and found after testing 110,000 such cigarettes that smokers “lost their desire to smoke tobacco cigarets for several hours,” suggesting this as one possible way to cut down. The Wall Street Journal reported that cigarettes of this sort produced “an odor akin to cabbage burning in a pan.”34

In the United States, commercial cigarettes have sometimes been made from plant derivatives judged unfit for human consumption—corn silk, for example—or inexpensive edible materials. The first factory for lettuce cigarettes was built in Hereford, Texas, in 1966 to sell Bravo cigarettes; sales by March of that year reached $50,000 but never went much further, apart from a couple of isolated markets. (In 1967 two of every hundred cigarettes smoked by students in Amarillo, Texas, the company’s test market, were made from lettuce.) Triumph cigarettes—another lettuce brand—were no more successful when introduced in 1969.

Interest in tobacco substitutes remained high throughout the 1960s and 1970s, however. Fred G. Bock at Roswell Park studied several different kinds of plants to find out which, when smoked, would produce the fewest carcinogenic tars. Beets, petunias, cabbage, dandelions, maple leaves, lettuce, and catalpa all came under scrutiny. One researcher attached to the French tobacco monopoly in the 1960s described a patent for a tobacco-free cigarette—the “Santab”—made from coltsfoot, lobelia, rose petals, and cinnamon. Cocoa cigars were smoked in France in the decades prior to the First World War, and this same researcher described these as “very much appreciated by children, who would procure them from the bakery or from the grocers.” Cigarettes were sometimes made from eucalyptus leaves, and chocolate cigarettes (for smoking!) for a time were made in a Marseille factory. Lots of other substitutes have been proposed: dried menthol, pulverized pine needles, coffee hulls, citrus pulp or pulp from sugar beets, algae in various forms, gum and pectin fillers of various sorts, a Celanese product known as Cytrel, and substances more generically characterized as “designed” or “low tar filler” (LTF).35

Tobacco makers of course have long used substitutes simply to save on costs. Laws against adulterating tobacco have been around since the nineteenth century, though many seem to have been poorly enforced. One common fad from the 1970s was to introduce nonburnable materials into the cigarette rod, much as you might reduce the calories in a certain volume of ice cream by pumping it full of air or some other inert filler. Materials added to cigarettes have included volcanic glass, ceramics, and various synthetic fibers and claylike materials. A number of British firms played this game: Peter Taylor in his Smoke Ring reports that some British cigarettes in 1977 contained 25 percent “new smoking material” (NSM), a tobacco substitute produced through a 20-million-pound cooperative venture between Imperial Tobacco and Imperial Chemical Industries. Millions of kilograms of NSM went into about a dozen new brands in 1977, none of which proved successful over the long haul, despite huge fanfares of publicity. As Taylor puts it, nonburnable tobacco substitutes were “a monumental flop.” Cigarette manufacturers had hoped that NSM would be welcomed as helping to make a “safer” cigarette, but Britain’s Health Education Council ridiculed the gimmick, comparing it to jumping from the thirty-sixth floor of a building instead of the thirty-ninth.36

The additives considered here are only a tiny fraction of those utilized by the industry—and a much smaller part of the universe of those considered for use. The archives reveal some ideas that, to anyone outside the tobacco labs, sound quite sinister. In the 1970s, for example, when many people thought marijuana might become legalized, the industry started exploring the possible use of “super-addictors” in tobacco (and perhaps in marijuana): scientists at British American Tobacco in 1977 pondered spiking its cigarettes with etorphine, a narcotic “10,000 times more addictive than morphine”—also known as “elephant juice” for its use in immobilizing elephants.37 The idea today sounds outlandish but is perhaps unsurprising given the industry’s long history of adding substances to influence a cigarette’s burn rate, smoke particle size, or nicotine potency—or even the whiteness of the paper or the color or integrity of the ash. Some companies have even added appetite suppressants, mindful of the fact that many women smoke to control their weight.

The archives also reveal tobacco manufacturers sometimes blindly adding substances about which they had no clue as to composition. BAT in the 1960s pressed one supplier, Sandoz, to reveal the composition of YOMARON, used by the company since 1950 as a bleach for cigarette paper. Sandoz eventually reported toxicity data to the company, but what is remarkable is that BAT didn’t even know its chemical composition during the first ten years it was being used in cigarettes. (Sandoz in 1960 revealed it to be a “diamino stilbene derivative containing triazine groupings.”) BAT regarded the Sandoz report as “clearing” the compound, even though the data were exclusively for ingestion and, according to BAT, “we still don’t know what happens on burning.” The company continued using this bleaching agent for several years thereafter, prior to deciding (in 1967) that it would be better to use “more desirable additives” serving this purpose.38

Safety has always been the odd man out in the cigarette business, and one thing we find in the archives is the presumption that a long history of use is justification enough for a compound’s continued use. BAT in 1967, for example, okayed the continued use of cocoa butter (code named CELMOE) on the grounds that cocoa enjoyed “a very long history of use at quite considerable levels.” Dosage was sometimes a consideration, as when BAT justified (to itself) its adding of ZAMPAR, an aldehyde supplied by International Flavours and Fragrances: “There is no reason why ZAMPAR should not be used on tobacco at an application rate of 1 oz. per 1,000 lb. cut tobacco,” given that it took 18.5 grams of the stuff per kilogram to kill half the rats exposed. (The British-metric mishmash is in the original.) More cautious, perhaps, was the suggestion that a compound known as Ketonarome (1-methyl-cyclopenta-2,3-dione) was to be added to cigarettes “at the lowest level necessary,” given evidence of ciliatoxicity for similar dicarbonyl structures. Formalin was likewise to be used (in starch pastes, to kill mold) “only as a last resort” because it was “physiologically active.” The philosophy in most instances seems to have been: assume safety unless you can prove otherwise. That was the approach in 1967, when Australian manufacturers asked about using two different flavorants for which BAT had recommended an upper safety limit. The question was whether one should worry about synergistic effects, and Sydney J. Green’s response at BAT was basically: in the absence of other information, assume no interactions.39 I’m not sure what name to give to this violation of “the precautionary principle” (reckless endangerment?), but in the cigarette world it seems to have been business as usual.

Some additives have been banned by national legislative bodies. Diethylene glycol is prohibited in cigarettes sold in Australia, for example, and coumarin has been banned in Germany. Maleic hydrazide was banned in Rhodesia in the 1960s, as already noted. British cigarette makers in the 1950s were barred from adding either sweeteners or humectants to tobacco, though they were permitted to add spices dissolved in rum (to improve the smell) and acetic acid (to reduce mold). A number of countries have banned the use of ammoniated tobacco sheet for purposes of freebasing, and there are bans on many types of tobacco products in different parts of the world.

In most parts of the globe, however, there are few restrictions on what can or cannot be put into cigarettes. The United States has historically been lenient in this regard—one could say profoundly negligent. Prior to 2009 the country had no rules governing what could be legally added to tobacco—apart from controlled substances such as opiates or barbiturates. The tobacco industry has a stated policy of using only additives approved for use in foods and “generally recognized as safe,”40 but that has been a purely voluntary code with no legal teeth and suffers from the already mentioned conflation of ingestion and combusted inhalation. Manufacturers of dog food are more careful—and humane—and if cigarette makers decided to make human feces or rodent hair an ingredient, there would seem to be no law stopping them. Smokers are not likely to know much about what goes into cigarettes and might well be surprised to find out the truth.