105

Interview with Jacob Bronowski for Associated Rediffusion Television (1962)*

Do you feel that your novels are larger than life?

I’m not sure this isn’t an illusion. For me, life is not an independent, objective entity. Its image depends on the observer. And there are too many observers—coming and going, and turning away, and looking again, and shading their eyes again—too many changing observers and changing lights, too many of them to enable one to establish an average picture of life. If you find I see life larger than life, this implies only a difference between you and me—not between life and my vision of life. We all are the makers of reality, and there are as many makers of reality as there are men. The real unreality is the conventional and the common.

But in Lolita you chose a rather grotesque and violent form of passion. Surely this is a deliberate choice, a dramatic sharpening and heightening so that the readers’ experience of life becomes larger than life.

I disagree. Life in the objective and neutral sense you give it does not really exist—so that one thing cannot be larger than another thing which does not exist.

Carbon copy of a question sent by Jacob Bronowski, answered by Nabokov, and typed out by Véra Nabokov or a secretary, for a 1962 television interview for Associated Rediffusion. Filming was canceled because of Dmitri Nabokov’s hospitalization.

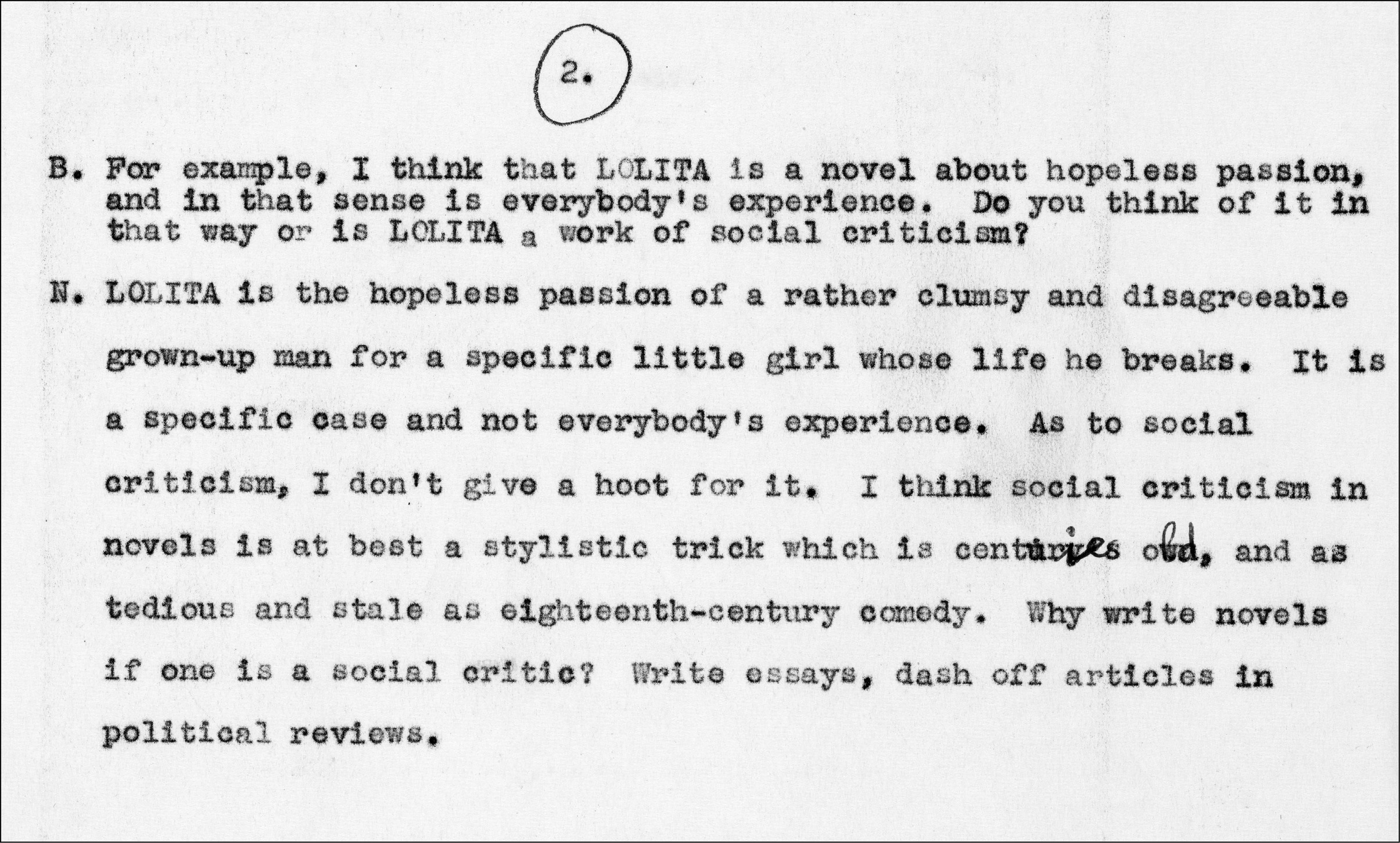

Do you think of Lolita as a novel about hopeless passion or is it a work of social criticism?

Lolita is the hopeless passion of a rather clumsy and disagreeable grown-up man for a specific little girl whose life he breaks. It is a specific case and not everybody’s experience. As to social criticism, I don’t give a hoot for it. I think social criticism in novels is at best a stylistic trick which is centuries old, and as tedious and stale as eighteenth-century comedy. Why write novels if one is a social critic? Write essays, dash off articles in political reviews.

The duel at the end of Lolita between Humbert and Quilty seems to me inspired fantasy. Or do you intend the reader to take it seriously?

I don’t think I could name a single striking scene in a worthwhile work of fiction that can be taken seriously in that sense. Only the conventional and common is serious or better say—solemn. Another special aversion of mine is the epithet “sincere.” How can a conjuror be serious or sincere—and a good artist is always a conjuror. To take some examples. Flaubert imposes a magnificent illusion on his readers when he describes Emma’s escapades which in so-called “real life” would have set tongues wagging long before the author was ready to dispatch his lady. Consider the nightly meetings of Emma and her lover in the garden pavilion. Can a reader take seriously the fact that Charles Bovary, a healthy young husband, never once turns to his young wife in the middle of the night to find the better half of the bed empty. Or take some of those impossible eavesdropping scenes in Proust—for example, that little affair between Charlues and Jupin. Or in Bleak House, that stunning chapter in which the sinful and ginful old man is literally consumed by internal and external fire. Who cares if all this does not conform to serious average life? Down with the serious and sincere reader. After all, not all readers are children who ask if the story is true.

I don’t think your two examples are alike. The escapades of Madame Bovary are made more plausible than they would be in average life, yes. But the man in Bleak House who dies by spontaneous combustion is not just implausible—he is incredible, a creature of fantasy. This is what I think about the scene between Humbert and Quilty. We believe it because it relieves our pent-up feelings, but it is unbelievable.

I think you are wrong. Art is always implausible since art is always deception; and the relief of pent-up feelings is generally the reaction of a very juvenile reader.

There is a strong visual sense in everything you write. Do you have a mainly visual imagination?

Let me put it this way: All the books I like—Hamlet, Dead Souls, Madame Bovary, Bleak House, Anna Karenin, The Passionate Friends, and a few others—have good eyes. And all the authors whom I find mediocre and tedious, such as Cervantes, Stendhal, Dostoevsky and many others, are dim-sighted or blind.

Did you enjoy turning Lolita into a film?

I did not turn it into a film. I only wrote the screenplay. This work took me six months. I composed the thing scene by scene, in a lovely green-and-blue Los Angeles canyon, in 1960. I hope to publish it someday.

It was great fun writing it.

What were the problems in making the novel into a film?

There were two problems involved—a general one and a specific one. The general problem is that of time. An ideal film should omit nothing, should follow the text phrase by phrase, and present visually every metaphor, every abstract thought. Even so, the result would be a stylistic compromise, a limitation of perception.

Do you think that the Film is as expressive as the Novel; will it take the place of the Novel?

What a bizarre thought! It is like saying that someday perhaps all novels will be published with illustrations. After all, you perceive a novel with your visionary mind, with your vibrant brain, and not with your physical eyes and ears. It would be rather disturbing for an author who, for instance, has taken great pains to build verbally a delicate, deliberately blurry image, to have some matter-of-fact chap with a camera come between him and his phrase.

This is not quite what I meant. The novel itself is quite a modern invention—the English novel is only 200 years old. Before that, writers told such stories in epic poems or in plays. Are we now coming to a time when creative minds find it more expressive to write directly in the visual imagery of the film?

I don’t think I care; all I know is that my creative mind is concerned only with written words, and not with photographed things shot and killed by a camera.

Can you conceive yourself thinking of a new work as a script for a film directly, and not as a novel?

Certainly not.

Is the exile especially characteristic of this age?

No. There are as many exiles and ages as there are banished men or banned minds. The term “this age” means nothing to me.

It seems to me that you are interested in universal and social situations, but that you always see them in very personal terms. Do you think that this is the essence of the novel?

I’m afraid I’m not interested in social situations or problems. As a writer I am practically immune to social or moral ideas. Moreover the novel does not exist for me as a generic idea. But specifically a few novels do—among which are Hamlet and Eugene Onegin, both written in verse. For me, the idea of a book lies in its main structural theme, which is a verbal thing, a stylistic phenomenon, just as one can speak of the idea of a musical composition or of a chess problem without any moral or social implications. Of course, there are some good readers who, among the more important matters, are interested in the social and moral ideas of a novel even if the author did not put them there; but alas, it is generally the bad reader whose lazy mind prefers the easy general idea to the difficult specific details of a work of art. This is why young simpletons all over the world love Dostoevsky—because it is so easy and fascinating to discuss mysticism and sin without reading him closely; and that is why my worst students (when I was a university professor) always preferred such second-rate fellows as Faulkner and Camus to any real artist.

For most of your life you have been a scientist. Do you think of your scientific work quite differently from your novels?

Though I have always hunted butterflies, I’ve been an active scientist—in the sense of probing certain taxonomic problems and publishing my findings—only for ten years or so—from about 1940 to about 1950. Otherwise I have always successfully combined butterfly hunting with my literary work. And generally speaking: I think there is a bond and a blend between art and science at suitable altitudes. Lowlands do not interest me. By science I do not mean those popular or unpopular technological gadgets that impress journalists. I mean natural science and pure mathematics.

You said at the beginning of this discussion that not all readers are children who ask if the story is true. Tell me how you think that science is true. Is the truth in a scientific theory more literal than in a work of art?

I did not say that science is truer than art. When a child demands truth it is the clamoring for a convention—not for truth but for an average fact that is held to be true. As to scientific theories, they are always the temporary gropings for truth of more or less gifted minds which gleam, fade, and are replaced by others. Both art and science are very subjective affairs.

Are you the same character when you are working with butterflies as when you are working on a novel?

No, not quite. In ordinary life, for example, I’m strictly right-handed, but when manipulating butterflies, I use my left hand more than my right. I am also much more nervous, much gloomier and greedier when hunting them. I emit strange sounds, curses and entreaties. Finally, we should all remember that a lepidopterist reverts in a sense to the ancient ape-man who actually fed on butterflies and learned to distinguish the edible from the poisonous kinds.

Do you think that scientists are as deeply and personally involved in their work as the novelist is?

I think it all depends on what scientists or novelists you have in view. Darwin or Gauss were as deeply and rapturously involved in their work as Browning or Joyce. On the other hand, in both camps we have those crowds of imitators, those technicians and administrators and career boys who cannot really be called scientists and artists. They, of course, dismiss their work from their minds after office hours.

Is there something personal and revealing about your choice of butterflies as a subject of study?

No, they chose me, not I them. It all started on a cloudless day in my early boyhood—started as a passion and a spell, and a family tradition. There was a magic room in our country house with my father’s collection—the old faded butterflies of his childhood, but precious to me beyond words—now almost a hundred years old, if they still exist. My mother taught me to spread my first swallowtail, my first hawkmoth. That enchantment has always remained with me. I have spoken of this much better in my memoir Speak, Memory.

Is there something personal and revealing about your choice of characters in your novels?

I suppose a novelist can’t help giving his pet notions to his intelligent characters, and giving his stupid characters such notions as he holds in contempt. It has been noticed that most of the people in my books, the clever ones as well as the fools, are always sort of nasty or half nasty—anyway, much nastier than I am in ordinary life. But generally speaking I object to being looked for in my books. And there is a sign over all my books: Freudians, keep out! And in case they don’t, I have laid a few little traps here and there.